1871 colUmbia & sappho defeat livonia

Columbia ‖ New York Yacht Club

Livonia ‖ Royal Harwich

LOA: 107ft 10in LWL: 96ft 5in beam: 25ft 6in draft: 5ft 11in draft with board: 22ft displacement: 220 tons

LOA: 127ft LWL: 106ft 6in beam: 23ft 7in draft: 12ft 6in displacement: 280 tons

sail area: not known owner: Franklin Osgood designer: J. B. van Deusen builder: J. B. van Deusen skipper: Nelson Comstock

Sappho ‖ New York Yacht Club LOA: 135ft LWL: 119ft 4in beam: 27ft 4in draft: 12ft 8 in displacement: 310 tons

D

sail area: 9060sq ft owner: Col W. P. Douglas designer: C. & R. Poillon builder: C. & R. Poillon skipper: Sam Greenwood

irectly after his arrival in England, following the defeat of his schooner Cambria in the first challenge for the America’s Cup, James Ashbury asked Michael Ratsey of Cowes to build him a new yacht expressly to win the Cup in 1871. This second challenge caused even greater controversy than in 1870, although it resulted in certain concessions being granted by the New York Yacht Club.

34

sail area: 18,153sq ft owner: James Ashbury designer: Michael Ratsey builder: Michael Ratsey skipper: J. R. Woods

No money was spared on Livonia and she was constructed of oak and teak to combine all that was best in English and American design. But so confident were the Americans in their choice from existing yachts that no new vessels were put on the stocks. However, in his correspondence with the New York Yacht Club before setting out, Ashbury had insisted upon his right to appear as the representative of no less than twelve yacht clubs, with the opportunity to sail twelve races on twelve different days. If he managed to win any one of these races the club he was representing on that day was to be awarded the Cup! The Club held a meeting to consider Ashbury’s proposals, but although they decided that he could represent only the Royal Harwich Yacht Club, they also conceded that he should not be put against the whole of their fleet, as in 1870! The Livonia sailed for America before the final details had been arranged and Ashbury continued to argue his case in New York until it was settled that he was to sail the best of seven races against any one of four defenders. On the day of the opening race there were as many spectators present as there had been the year before. Two keel schooners, Dauntless and Sappho, and two centreboard schooners, Palmer and Columbia, had been selected to defend the Cup, but Columbia was the first to establish her superiority over the British boat. Gaining three minutes before the Narrows she never gave Livonia a chance and won by a wide margin.

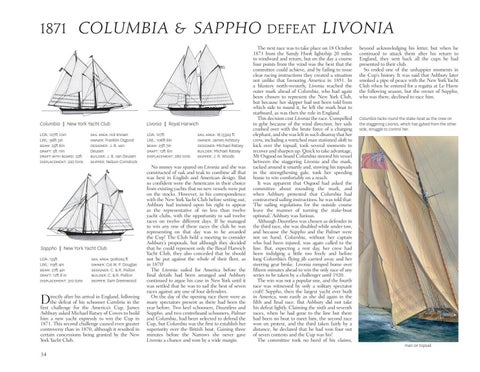

The next race was to take place on 18 October 1871 from the Sandy Hook lightship 20 miles to windward and return, but on the day a course four points from the wind was the best that the committee could achieve, and by failing to issue clear racing instructions they created a situation not unlike that favouring America in 1851. In a blustery north-westerly, Livonia reached the outer mark ahead of Columbia, who had again been chosen to represent the New York Club, but because her skipper had not been told from which side to round it, he left the mark boat to starboard, as was then the rule in England. This decision cost Livonia the race. Compelled to gybe because of the wind direction, her sails crashed over with the brute force of a charging elephant, and she was left in such disarray that her crew, including a wretched man stationed aloft to kick over the topsail, took several moments to recover and sharpen up. Quick to take advantage, Mr Osgood on board Columbia steered his vessel between the staggering Livonia and the mark, tacked around it smartly and, stowing his topsails in the strengthening gale, took her speeding home to win comfortably on a reach. It was apparent that Osgood had asked the committee about rounding the mark, and when Ashbury protested that Columbia had contravened sailing instructions, he was told that: ‘The sailing regulations for the outside course leave the manner of turning the stake-boat optional.’ Ashbury was furious. Although Dauntless was chosen as defender in the third race, she was disabled while under tow, and because the Sappho and the Palmer were not on hand, Columbia, without her captain who had been injured, was again called to the line. But, expecting a rest day, her crew had been indulging a little too freely and before long Columbia’s flying jib carried away and her steering gear broke. Livonia romped home over fifteen minutes ahead to win the only race of any series to be taken by a challenger until 1920. The win was not a popular one, and the fourth race was witnessed by only a solitary spectator craft! Sappho, then the largest yacht ever built in America, won easily as she did again in the fifth and final race. But Ashbury did not take his defeat lightly. Claiming the sixth and seventh races, when he had gone to the line but there had been no boat to meet him, the second race won on protest, and the third taken fairly by a distance, he declared that he had won four out of seven contests and the Cup was his! The committee took no heed of his claims,

beyond acknowledging his letter, but when he continued to attack them after his return to England, they sent back all the cups he had presented to their club. So ended one of the unhappier moments in the Cup’s history. It was said that Ashbury later smoked a pipe of peace with the New York Yacht Club when he entered for a regatta at Le Havre the following season, but the owner of Sappho, who was there, declined to race him.

Columbia tacks round the stake-boat as the crew on the staggering Livonia, which has gybed from the other side, struggle to control her.

man on topsail