5 minute read

The Paintings

1851 America defeats the british fleet

America ‖ New York Yacht Club

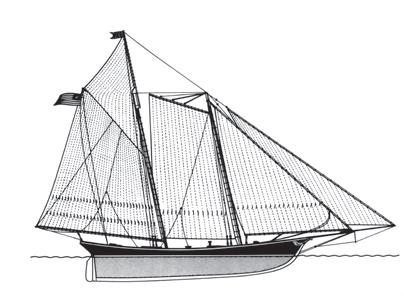

LOA: 101ft LWL: 90ft beam: 23ft draft: 11ft displacement: 170.55 tons sail area: 5263sq ft owner: John Stevens and syndicate designer: George Steers builder: William Brown skipper: Chas Brown

During the mid-nineteenth century the American clipper ships and pilot boats were probably the most seaworthy and speedy craft in the world. By 1851, the year of the first World’s Fair, a great international exposition to be held in London, American boat builders had become famous among seamen of every nation. Encouraged by the promoters of the Fair, some New York businessmen therefore persuaded John C. Stevens, Commodore of the recently formed New York Yacht Club, to commission a yacht to compete against the British for money. She was to be named America.

The Commodore had a talk with his friends Hamilton Weeks, George L. Schuyler, James Hamilton and J. B. Finlay and they decided to ask George Steers, the son of a Devonshire shipwright, who had designed many successful pilot boats, to draw them a fast schooner of about 90ft (30m). William Brown, whose yard was chosen to build her, became so enthralled with the project that he offered to complete America for £30,000 ($45,000) to be paid out of his own pocket if she failed to beat all opposition. The syndicate agreed that such an offer should not be declined.

America sailed from New York early in June 1851, bound for Le Havre. As the crew battened down for the open sea, ‘Old Dick Brown’, a Sandy Hook pilot, who had been entrusted with the command of the little boat, thundered: ‘If there be a white-livered dog among you who wants to step ashore, now is the time to yelp.’ Not a man yelped but one of the nine crew climbed up on a hatch and raising his cap called for three cheers for the ship and skipper Brown. The passage took them twenty-one days; it was, in fact, the first time that a yacht had crossed the Atlantic in either direction.

Commodore Stevens joined her in France, where, with help from her designer George Steers, she was prepared immediately for battle with a racing rig. As soon as she was ready she sailed for Cowes on the Isle of Wight, which was then, as it is now, the yachting headquarters of Great Britain.

Commodore Stevens had a sack of gold coins in his cabin and because it was his intention to wager enough money to more than recover the cost of the boat, he was determined not to show his hand too soon. But his plans were to come to naught.

Forced to wait for daylight 6 miles from Cowes, America was met by the cutter Laverock, a very fast yacht, which had courteously arrived to escort her and incidentally get a feel for her performance. It would have been the easiest thing in the world to have let Laverock beat America to the shore, but the blood was already running too hot in the Commodore’s veins. In no way could he resist a contest, and the British yacht was thrashed soundly.

The British did not know what to make of America. The Times reported: ‘She has a low black hull, and two noble sticks of extreme rake without an extra rope. When close to her you see that her stem is as sharp as a knife blade, scooped away until she swells again towards the stern.’ The absence of a jib boom and a fore topmast surprised the opposition, and although it was the custom in England to cut baggy sails to hold the wind, the America’s sails were as flat as boards.

The news that the Yankee schooner was fast spread like wildfire and Stevens was unable to lay a single wager. The only prize that the Royal Yacht Squadron were prepared to put up was a cup valued at 100 guineas (about $180), which was to be awarded to the winner of an international regatta to be held on 22 August as part of the celebrations for the World’s Fair.

On the morning of the race, more spectator craft gathered off Cowes than had even been seen together in the history of yachting. The preparatory signal was fired at 09.55 from the Squadron battery and most of the fifteen competitors, anchored in a double line, got under way smartly, although America seemed in no mood to hurry. At 10.00 the starting gun boomed out and the fleet sailed away to the east with America scything through the opposition until she was lying in fifth position.

‘Old Dick Brown’, at the helm of America, was by now being so severely jostled that he decided to break away and pass inside the Nab light vessel which marked the eastern end of the course. The wind was blowing up from the south-south-west and there is no doubt that the manoeuvre gave him a considerable advantage over the leading boats standing off to pass round the Nab.

Followed by the remainder of the British fleet, America, now with a ‘bone in her teeth’, romped towards St Catherine’s Point, losing her flying jib on the way. Although two yachts, Freak and Volante, made up some ground tacking close under the cliffs, they unfortunately collided, and when shortly afterwards Arrow went aground, with Alarm standing by to give assistance, America was out on her own. She reached the Needles at 17.30 some 8 miles ahead of Aurora, and when she met and saluted the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert, she was the only boat in sight.

The following morning the owner of Brilliant, the fifth boat to finish, formally protested that America had passed the wrong side of the Nab light vessel and should be disqualified. But this was promptly overruled by the Earl of Wilton, Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron, who explained diplomatically that an observer from the Squadron and a local pilot had sailed on board America and that by mistake she had been given two different sets of racing instructions.

Some were suspicious that America had won because of a secret propeller, but other more aspiring yachtsmen examined her advanced design. One, the Marquis of Anglesey, said after long deliberation: ‘I’ve learned one thing. I’ve been sailing my yacht stern first for the last twenty years!’

As America passes inside the Nab light vessel, pushing against the tide, her afterguard watch as Arrow, Bacchante (hidden), Constance and Gypsy Queen conform to ‘the other set of rules’. The Volante, followed by Aurora and the remainder of the fleet, alters course and gives chase.