6 minute read

The Research

1870 MAGIC defeats cambria

Magic ‖ New York Yacht Club

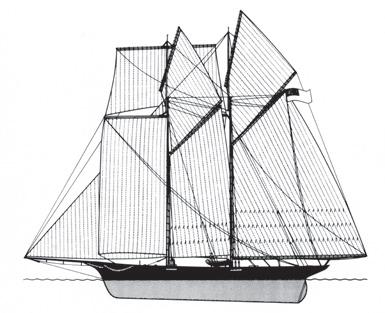

LOA: 84ft LWL: 79ft beam: 20ft 9in draft: 6ft 3in draft with board: 17ft displacement: 112.2 tons sail area: 1680sq ft (lowers only) owner: Franklin Osgood designer: R. F. Loper builder: T. Bylerly & Son skipper: Andrew Comstock

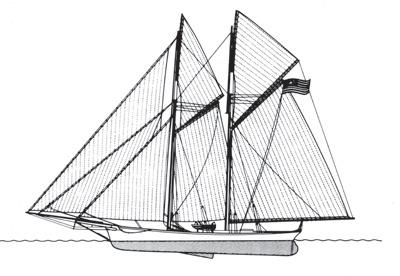

Cambria ‖ Royal Thames

LOA: 108ft LWL: 98ft beam: 21ft draft: 12ft displacement: 228 tons sail area: 8602sq ft owner: James Ashbury designer: Michael Ratsey builder: Michael Ratsey skipper: J. Tannock

After the America’s heroic win in 1851, her syndicate sold her in England to Lord de Blaquiere, but they continued showing off the Cup in their respective homes until in 1857 George Schuyler had the bright idea of saving on the silver polish by presenting it to the New York Yacht Club as an international yachting trophy. In a letter sent to the Club, later known as the first Deed of Gift, the syndicate made certain stipulations, concluding: ‘It is to be distinctly understood that the Cup is to be the property of the Club, and not of the members thereof, or owners of the vessels winning it in a match; and that the condition of keeping it open to be sailed for by yacht clubs of all foreign countries, upon the terms above laid down, shall forever attach to it, thus making it perpetually a Challenge Cup for friendly competition between foreign countries.’ But, as it happened, the Yankees were given twelve more years to crow about their victory and when battle recommenced there was nothing friendly about it at all.

British yachtsmen had misguidedly been in no hurry to take up the challenge, for in America there had been a rapid decline in yachting due to the Civil War. During this period several boats, following the America’s example, sailed in English waters, including Fleetwing, Henrietta and Vesta, which raced across the Atlantic for the first time in history. The race, won by Henrietta in just under fourteen days, was unfortunately marred by tragedy when six men were swept off Fleetwing by a giant wave, and generally the expedition was to have little success. More significant, however, was the arrival in 1868 of the large American schooner Sappho, sent across by her owners to be sold. Although she had acquitted herself well in the United States, they gave strict instructions that she was not to be tested but, as had happened in 1851, her skipper could not resist the temptation, and in a race held once again around the Isle of Wight she was soundly beaten by four British yachts including Mr James Ashbury’s Cambria, which won.

It was this that no doubt encouraged Ashbury, a man who had made a fortune on the railways, to write to the New York Yacht Club during 1869 initiating the first challenge for the America’s Cup.

The tedious correspondence which followed became almost acrimonious at times, and the details were debated to such lengths that no match could be arranged until the following season. Among his many requirements Ashbury insisted that, as per the rules of the Royal Yacht Squadron, centreboarders should not be eligible to compete, but the New York Yacht Club, turning a deaf ear, countered that his own challenge was unacceptable as it had not come through a recognised yacht club, and Ashbury was thus forced to challenge instead through the Royal Thames. Another of Ashbury’s proposals had been that he should race against their boat across the Atlantic and then around Long Island, but although the committee agreed to the first part, the second idea was never settled, and when the Cambria subsequently defeated the American schooner Dauntless on their passage to New York, it became clear why no decision had been reached. The New York Yacht Club had no intention of handing over the Cup on a plate, and when they argued that the terms should be similar to those of the first match, Ashbury realised that the New York Yacht Club were intending to knock him out with all the guns that they could bring to bear.

That the Cambria should now be asked to take on the Club’s entire fleet seemed not a little unsporting, and to many it was a gross misinterpretation of the Deed of Gift. It was one thing for a yacht like the America to join in and win a friendly club race, but quite another for a yacht to be taken on by a well-prepared and hostile armada, intent only on preventing the Cup leaving the country. The Deed definitely talked about a match, not a war, and although it could have been said that America had been jostled by a number of British competitors in 1851, nothing quite compared with the treatment planned for the gallant Cambria in 1870!

The New York Yacht Club had invited Ashbury to sail a single race over a course starting off Staten Island and thence through the narrows and round the Sandy Hook lightship, a distance of about 36 nautical miles. The morning of 8 August, the day set for the race, broke with leaden skies, and when Cambria and her eighteen opponents took up their stations the challenger was generously given the weather end of the line. According to the custom of the day the start was from anchor, all the yachts being drawn up with their chains short and their sails down, and as the signal was given there was feverish activity as the crews sweated at the windlasses and struggled with the halyards to hoist the sails.

The best position was, as it happened, of no benefit to Cambria, for as the sun broke through the wind shifted from the south-west to the south-east, making her the most leewardly boat of the fleet. Among the large number of spectator craft gathered to witness the inaugural defence of the America’s Cup stood out a tug bedecked with British colours, and as Cambria got under way the tug’s brass band blared out ‘Rule Britannia’, but all to no avail. She had a poor start and was immediately besieged by most of the boats around her.

The little centreboard schooner Magic was the first away, and with the advantage of her shallower draft she was able to stand over towards the shore and establish a convincing lead, but by the Spit Buoy the old America, which had been hastily fitted out by the Navy Department to defend her title, had almost caught her up. It was soon after this that Cambria, who was already nineteen minutes behind, was struck by another boat, losing a port shroud and her fore topmast-backstay, the Spirit of the Times subsequently reporting, ‘she suffered a little delay by being fouled by Tarolinta, which, being on the starboard tack should have kept away’. Magic went on to win, but Cambria, probably as a result of this collision, lost her fore topmast as she gybed for the run home, and could not manage better than tenth place, finishing some fourteen minutes behind America.

Thus the first attempt to lift the Cup had failed but, undaunted, Ashbury continued racing for a time in America. Finally, at last confident that the New York Yacht Club would ease the rules, he took his boat home and sold her as a trading vessel, Cambria later making money for her owners on the west coast of Africa in the humbler occupation to which fate had condemned her.

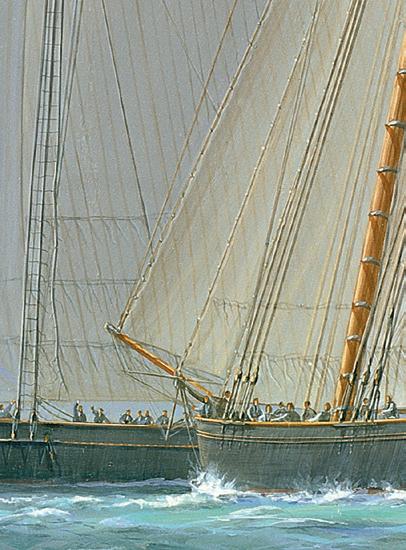

As Magic, pursued by the America, makes for the Sandy Hook lightship, Cambria is fouled by the Tarolinta, which carries away part of her rigging while going about.