FOREWORD

‘No true disciple of mine will ever be a “Ruskinian”!’ With characteristic wit and paradox, Ruskin lays down a challenge to anyone writing a book intended to celebrate the remarkable revival of interest in his work, ideas, and values over the past fifty years. Does the author adopt the uncritical role of disciple, or work from Ruskin’s own principles, by questioning, provoking, and above all, truth-seeking? In this respect, Suzanne Fagence Cooper is a Ruskinian, a member of an ever-growing international constituency of people who find in Ruskin’s life and work something richer than is usually found in that of his fellow Victorians. Some of that interest is academic, but as you will see, it reaches much further than that, as people – including academics – appreciate that Ruskin has something to say about twenty-first-century problems.

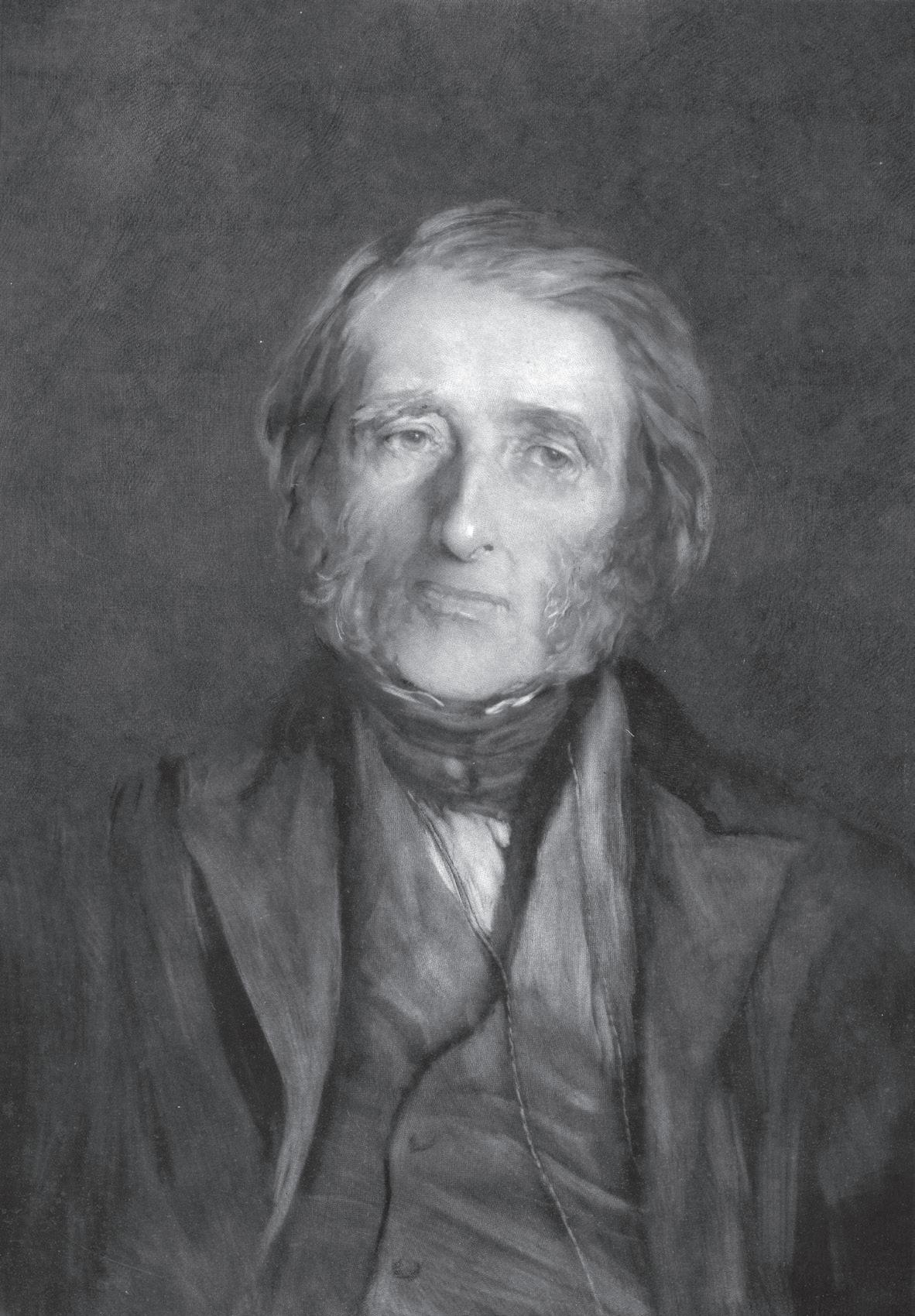

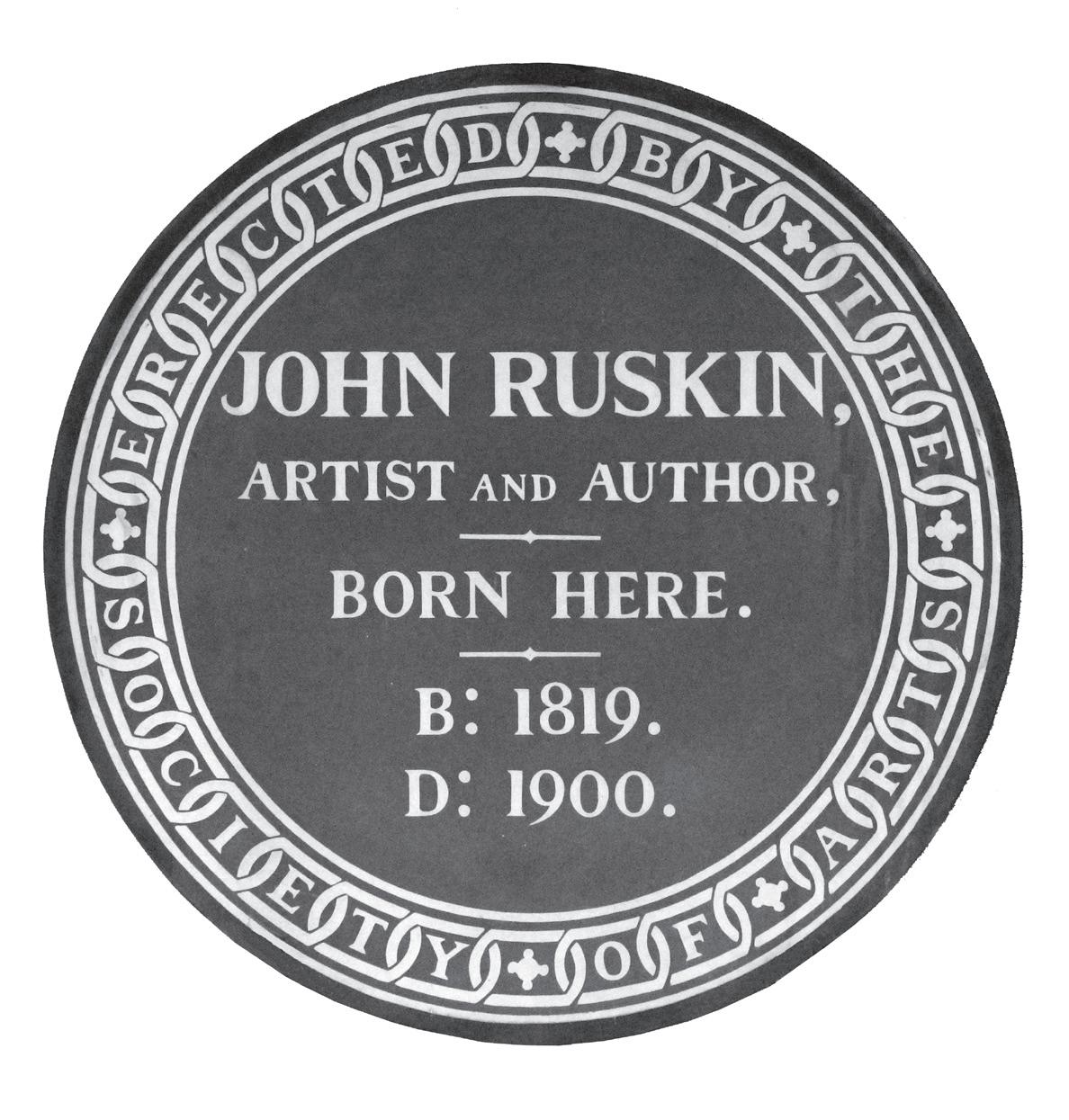

This book appears in the bicentenary year of Ruskin’s birth in 1819. There is no getting away from the fact that following his death in 1900, Ruskin’s ideas fell far out of fashion. But they did not disappear, and we must all acknowledge the key role played by one of the first Ruskinians, J. H. Whitehouse (1873-1955). He collected Ruskin manuscripts and drawings, and eventually bought Ruskin’s last home, Brantwood, as a national memorial. Whitehouse, and those who inherited responsibility for both house and collection, together with the school he founded on Ruskinian lines, are rightly celebrated in these pages. Appropriately, this book begins at Brantwood in 1969, just as a new interest in Ruskin was gaining momentum.

The other institution whose roots reach back to Ruskin is

the ruskin revival: 1969-2019

Since 1969 these two key institutions have been joined by a third: Lancaster University took the bold and creative decision to offer shelter to J. H. Whitehouse’s collection, and build the Ruskin Library, opened in 1998. As we learn, Ruskin scholarship has been pursued in many universities, both in Britain and North America. But the Ruskin Library, as an archive and active research centre, with a pioneering approach to digitisation, has given a focus to that scholarship. It has ensured the proper conservation of the Whitehouse collection itself. The Ruskin Seminar must be one of the longest-running programme of discussions devoted to a single figure in the world.

It would be un-Ruskinian, however, not record that all three institutions have faced challenges in the past fifty years, and untruthful not to do so. More importantly, the Ruskin revival has never been due to institutions alone. It is the people in these institutions, and the many people outside them, both academics and enthusiasts, who have made it possible. As this book shows, the range of individual approaches to Ruskin is astonishing, but their common characteristic has been mutual respect and cooperation. As Ruskin said: ‘Government and co-operation are in all things the Laws of Life; Anarchy and competition the Laws of Death’. This principle is exemplified by the network Ruskin To-Day – ‘To-Day’ being Ruskin’s urgent motto. Originally

x the Guild of St George. The utopian society which he founded has managed to endure the vicissitudes of Ruskin’s later years, and the decades of Ruskin’s obscurity that followed. As we read here, the Guild has not just preserved the physical legacy represented by the museum that Ruskin created in Sheffield, but has truly brought him into the twenty-first century with projects and campaigns that draw on Ruskin’s social message: ‘There is no wealth but life’.

brought together to co-ordinate the many individual plans that were being laid to celebrate Ruskin’s centenary in 2000, its membership is entirely voluntary. It has no constitution, and no bank account, but it has proved sufficiently useful to continue meeting until now, and contribute to the bicentenary of 2019.

Suzanne Fagence Cooper has travelled far and talked to a great many people in the course of writing this book. I am sure she would wish me, on her behalf, to thank all those who have helped her, and apologise to anyone whose names do not appear. Ruskin’s remit, his writings, and now the writings about him make it impossible to cover every aspect, even in an account as comprehensive as this.

The Ruskin Revival: 1969-2019 is a story with a happy ending that is at the same time a new beginning. In 2019 the co-operation between the guardians of the Whitehouse Collection and Lancaster University bore fruit when ownership of the collection was permanently transferred to the University, thanks to the support of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund and other donors. The University was already financing the operation of the Ruskin Library. Now its resources will support an expanded Ruskin Centre for Culture, Landscape and the Environment. As both the Guild of St George and the Ruskin Library acquire new leadership, Ruskin’s future is secure.

In 1969, to show an interest in Ruskin was still regarded as a little eccentric. I know that, because I began my own studies that year, as a result of visiting Brantwood. As Suzanne Fagence Cooper so admirably reveals, this is no longer the case. But she has rightly kept a certain critical distance, as well as giving all the credit where it is due. Disciple or not, that is what a true Ruskinian should do.

Robert Hewison, Ruskin To-Day

CHAPTER I

RUSKIN: 1969-2019

A strong old mulberry tree, a tall white-heart cherry tree, a black Kentish one, and an almost unbroken hedge, all round, of alternate gooseberry and currant bush; decked, in due season … with magical splendour of abundant fruit: fresh green, soft amber, and rough-bristled crimson … clustered pearl and pendant ruby … The differences … between the nature of this garden, and that of Eden, as I had imagined it, were, that, in this one, all the fruit was forbidden; and there were no companionable beasts.

John Ruskin, ‘Herne-Hill Almond Blossoms’, Præterita , 1885

1969

The spring of 1969 was marked by a death on a farm in Worcestershire, and a rebirth in the appreciation of Ruskin, at his last home in the Lake District, Brantwood. Ruskin’s hope for his readers had always been multi-faceted: emotional, intellectual and practical. His writings were restorative, urging his audiences back to the land, and back to the library.

Cuthbert Quayle, whose family had helped to keep Ruskin’s memory alive since his death in 1900, died in February 1969. From 1914 Quayle had lived in the heart of the Wyre Forest, on

Opposite: Fig. 2: New growth: fresh ferns growing in Ruskin’s Brantwood garden, 2019

the ruskin revival: 1969-2019

a farm given to the Guild of St George, the utopian society that Ruskin had founded. It became known as Ruskin Land. Quayle’s house was in a clearing among ancient oaks, damson, apple and cherry trees. An early settler on this land near Bewdley, he had arrived with his parents from Liverpool as a teenager. The Quayles intended to make a life at Uncllys Farm, inspired by Ruskin’s call to action in Unto This Last and Fors Clavigera, and his vision of taking ‘some small piece of English Land, beautiful, peaceful and fruitful’ to create a new community.

Cuthbert Quayle was one of the last direct links to that original utopian enterprise: he had been born in 1897 and grown up with the writings of Ruskin. Since his death, responsibility for the farms and the Guild’s land in the Wyre forest passed into the hands of his nephew, Cedric, and other younger Guild Companions. Cuthbert’s death in the early spring of 1969 can be seen as a tipping point, when those who could remember Ruskin’s lifetime made way for those who were encountering him as a voice from history. Within a month, a new generation of Ruskin enthusiasts was meeting at Brantwood, for a conference to celebrate Ruskin’s life and legacy. As they looked out towards the snow-tipped ridges of the Old Man of Coniston this international group shared scholarship, and good fellowship. Their enthusiasm would ensure that Ruskin’s teaching and writing began to find a fresh audience.

Ruskin’s insistent messages had been retold widely up to the Great War, and still carried weight through the early years of the Welfare State. But by 1969, they were fading. As Kenneth Clark had pointed out, ‘For almost fifty years, to read Ruskin was accepted as proof of a possession of a soul’.1 But by the late 1960s, his sermons on art and architecture, his exhortations to renew society and political economy, had become a marginal

ruskin: 1969-2019

interest, read by a few scholars, artists and political activists. Ruskin’s flowing paragraphs were whittled down to epigrams and trotted out to add gravitas to a news story or book review. A Times article on colour television – ‘By Christmas, the three colour channels (two BBC and one Independent) will be providing over 100 hours of colour programmes a week’ – began by quoting Ruskin: ‘The purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love colour the most’.2 However, the journalist immediately questioned whether Ruskin was right. He was an authority of sorts, but not to be taken too seriously. He occasionally provided a clue for the Times Crossword: ‘Ruskin’s dusty answer’, (answer: Ethics , Friday 25 July 1969), and his ‘illuminating septet’, (answer: Lamps, Monday 3 Nov. 1969). But his words had lost their urgency.

In the late 1960s no Liverpool family would leave their home, to live at the end of a cart track in the woods beyond Bewdley because they had read Ruskin’s letters to the workers of England, with his encouragement to ‘do the best you can for all men’, as ‘St. George’s soldiers’. Ruskin’s militaristic, overtly religious tone – ‘You are called into a Christian ship of war’ – had become distasteful to many in the post-1945 generation.3 The small community in Ruskin Land continued to prune, and plant, and become Companions of the Guild. But Ruskin’s reputation was at a low ebb.

Reading Ruskin was an effort. His collected works, gathered in the 39 volumes of the Library Edition , were daunting. They had been assembled with such care by his editors E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, but now too often they collected dust on the top shelves of antiquarian booksellers. His works were no longer common currency. Cook and Wedderburn had insisted that ‘everybody knows the passage’ describing the gold

the ruskin revival: 1969-2019

and blue and green of scented Alpine meadows from Ruskin’s 1849 diary. That might have been the case in 1912. But by 1969, the intensity of public engagement with Ruskin had faded. Kenneth Clark continued to champion Ruskin’s writing. He published a new edition of Ruskin’s autobiography, Præterita , in 1949, and an anthology of his own favourite extracts in Ruskin Today (1964). But attention was shifting away from the texts and towards Ruskin’s watercolours and drawings, with two significant shows created by the Arts Council: a touring exhibition of Drawings by Ruskin , 1960, and Ruskin and his Circle, 1964, curated by Elizabeth Davison. Again, Clark was involved, writing the foreword for both catalogues, but the lustre had come off Ruskin’s reputation.

For those who wanted to understand the man behind the words and watercolours, Derrick Leon’s biography, Ruskin the Great Victorian (1949) was reprinted in 1969, in time for the 150th anniversary of his birth. The American scholar John Rosenberg had offered an alternative psychological insight, in The Darkening Glass : A Portrait of Ruskin’s Genius (1961), foregrounding Ruskin’s struggles with mental health. Yet these representations of ‘greatness’ and ‘genius’ were increasingly at odds with the tenor of academic and public interest in nineteenth-century figures. As the heir of Bloomsbury attitudes to the Victorians, Quentin Bell, put it, Leon’s version of Ruskin was ‘tiresomely heroic’, and would no longer do.4

The revelations of Mary Lutyens’s Effie in Venice (1965) reignited interest in Ruskin’s personal life among general readers, and further undercut his stature as an eminent Victorian. Curiosity about his marriage to Effie Gray was not new – it had been stirred up by The Order of Release (1948), a hostile account of the annulment of the marriage by Effie’s grandson, Admiral

4

1969-2019

James, and J. H. Whitehouse’s defensive reply, Vindication of Ruskin (1950) – but Lutyens gave the first opportunity for many of Effie’s letters to be read at length. Lutyens’s article, ‘Where did Ruskin sleep?’ published in the New Year 1969 edition of the Times Literary Supplement and her further editions of letters, in Millais and the Ruskins (1968) and The Ruskins and the Grays (1972) only increased the speculation among mainstream press and gallery-goers about his intimate relationships.

By 1969, many academics treated Ruskin as a marginal figure. He was antipathetic to the new, more theoretical approaches that were opening up literary criticism, and filtering through English Literature and Art History teaching. Since Barthes had flung his theory of ‘the death of the author’ into critical debates in 1967, texts and images were no longer tied to their maker. Instead they could, indeed should, be treated ahistorically. How could Ruskin be read in this way? He was a constant presence in all his writings, a master of hypercontextualisation and interconnectedness. To read Ruskin, without understanding the hooks and eyes of his observations, or how he worked with his audience, cajoling, demonstrating, urging, was to empty out his writings, to leave them almost meaningless. He had always been difficult to squeeze into a syllabus; now, confined by his Victorian language, he was even more likely to be side-lined.

For those few who persisted in researching and teaching Ruskin, there were difficulties in even accessing the primary sources. Joan Evans and John H. Whitehouse had opened up new possibilities with their edited volumes of Ruskin’s Diaries (3 volumes, 1956, 1958 and 1959). This substantial feat of teasing out and decoding revealed Ruskin’s intellectual development and self-scrutiny to scholars around the world. But by concentrating on the purely biographical information in the diaries,

and excluding much of his notes on his thinking and reading the editors were guilty of significant omissions. Most notably, as Ruskin’s most devoted American scholar, Helen Gill Viljoen was to point out, Ruskin’s Brantwood diaries from 1876-1883 had not been included, though they were ‘directly relevant to Ruskin’s long struggle against insanity’. The reason was that the Ruskin collector, who owned the manuscript, F. J. Sharp, had been ‘unwilling’ for this to be part of the official account of his life. 5

This was only one repercussion of the dispersal of Ruskin’s estate back in the 1930s. There were many others. Ruskin studies had no clear focal point. Scholarly engagement was hampered, both by Ruskin’s generous gifts in his lifetime, and by the breaking-up and sale of his home at Brantwood by his heirs in the early twentieth century. Letters, diaries, drawings, Turner watercolours and personal objects, were scattered on both sides of the Atlantic. Some were owned by individuals like F. J. Sharp, others by institutions including the Ashmolean Museum, Yale University and the Morgan Library in New York. The objects given by Ruskin to the museum he had created in the 1870s for the Guild of St George were largely still in their packing crates in the bowels of Reading University, having been removed from their original home in Sheffield. The most important extensive collection, which had once belonged to J. H. Whitehouse, was privately held at Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight.

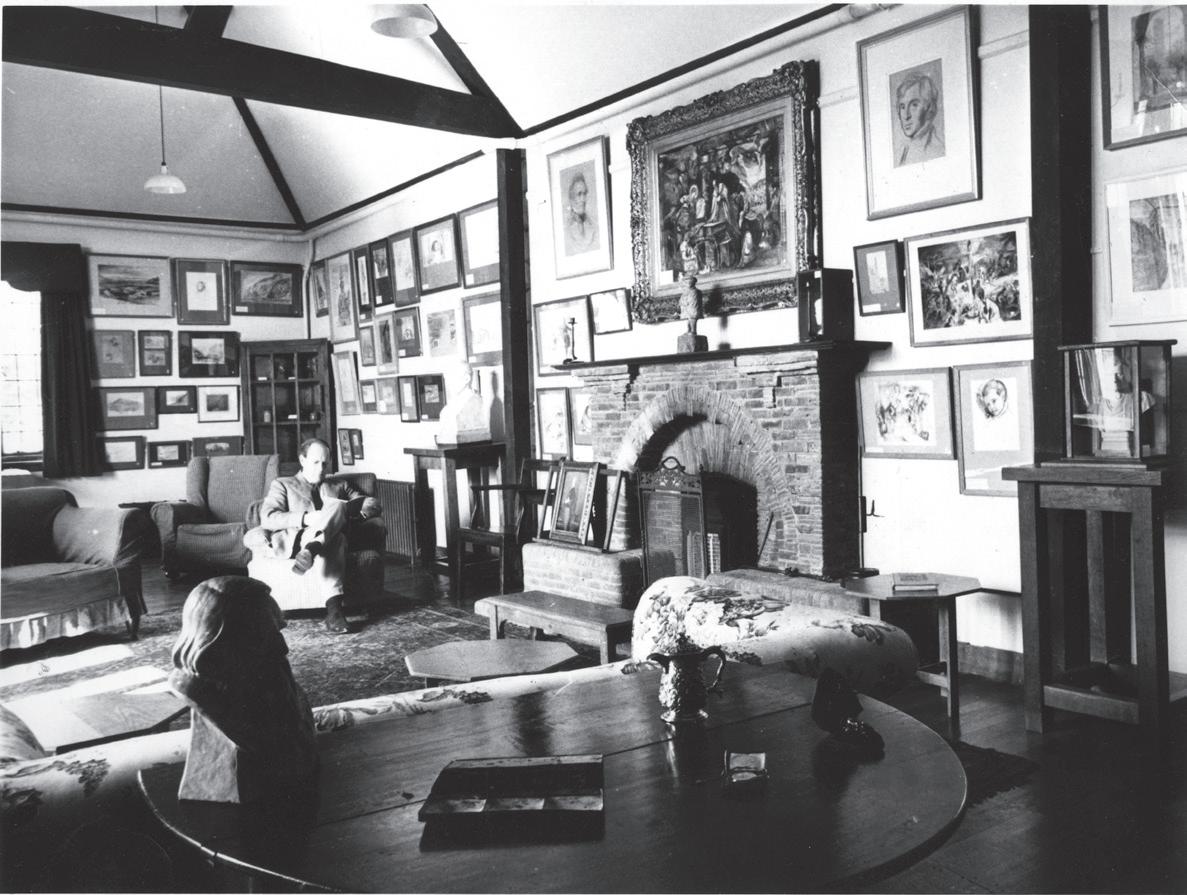

James Dearden, curator at Bembridge, nonetheless was steadily cataloguing and sharing his knowledge of the numerous manuscripts, books and pictures in his care, with frequent redisplays in the school’s small gallery, and articles in Apollo and Connoisseur. 6 Yet despite his best efforts, there were many obstacles to research; only the most ardent Ruskinians made the ferry crossing to the Isle of Wight. Helen Viljoen visited

the ruskin revival: 1969-2019 6

ruskin: 1969-2019

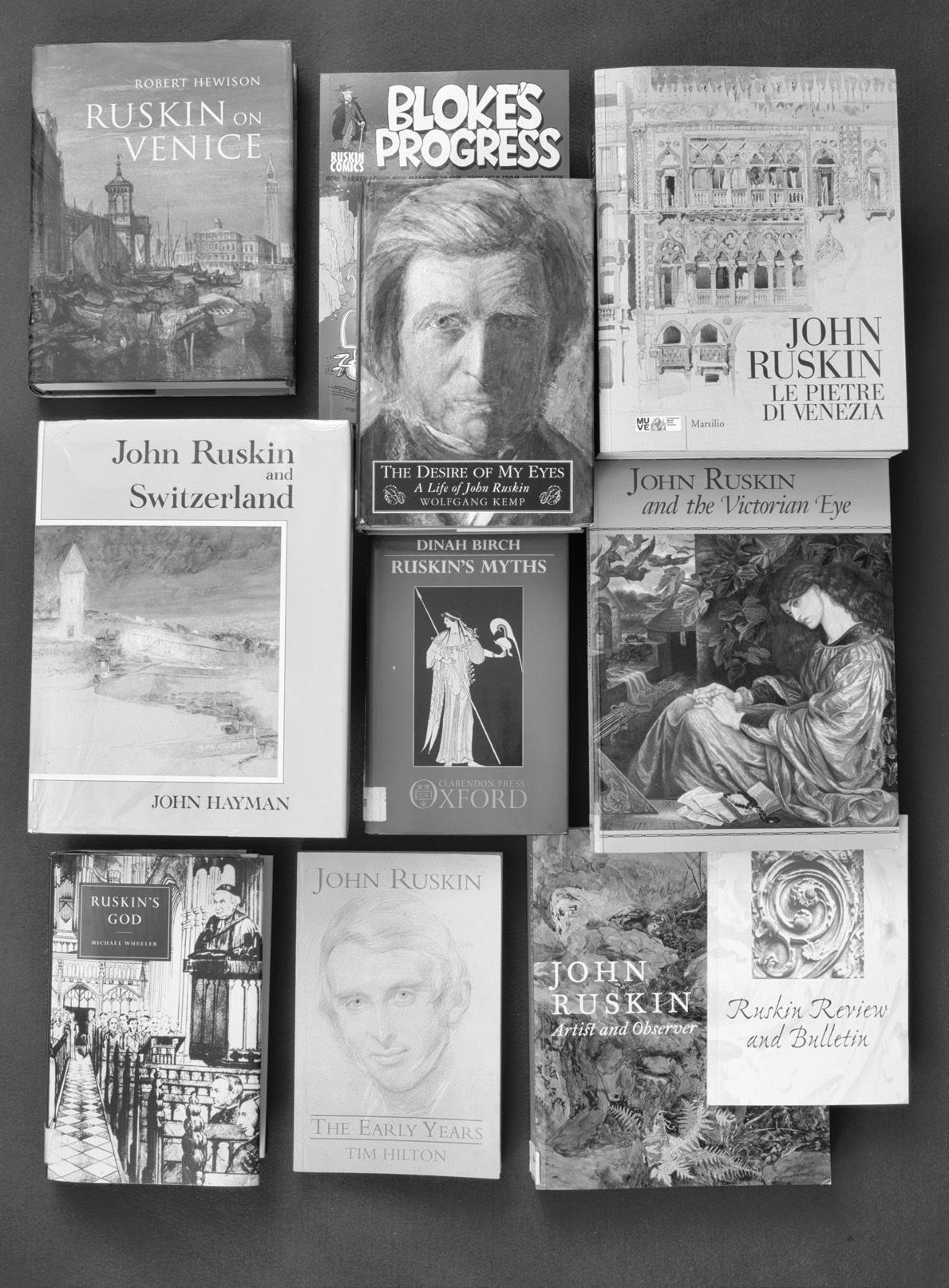

Fig. 3: New books: a selection of Ruskin publications since 1969

8 Bembridge in the 1960s, as did her fellow American scholar Van Akin Burd, who had been writing on Ruskin since the mid-1950s. 7 Even Tim Hilton, when he began work on Ruskin’s biography some decades later, found it a cold, lonely task, working systematically through the Whitehouse papers. The opening up of the collection at Bembridge was part of a slow process of re-engagement with academics and art audiences. Little by little, more of Ruskin’s words and images were edited and reproduced. Hilton applauded the combination of personal and institutional efforts that made this possible. He honoured the many ways that ‘knowledge of Ruskin has been handed down by professional help and generosity’, 8 a process that is still continuing. The Ruskin community is splendidly diverse. Ecologists, poets, curators, archivists, university

Fig. 4: James Dearden in the Upper Ruskin Gallery, Bembridge School, c 1958

1969-2019

academics can all claim, rightly, to be Ruskinians. And they are open and encouraging about Ruskin projects beyond their own fields – including my research for this book.

The decision to hold an academic conference at Brantwood in 1969 – the one-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Ruskin’s birth – was a key moment in this process of sharing and renewal. Dearden, backed by Rhys Gerran Lloyd, who as Chairman of the Education Trust Ltd was responsible for maintaining both Bembridge School and the Whitehouse collection, opened conversations that would transform how Ruskin was seen and heard by the wider world. The revival in Ruskin studies had begun.