1 hisTorY

“Today, praise be to God, wine was pressed for the first time from Cape grapes, and the new must fresh from the tub was tasted. It consisted mostly of Muscadel and other white round grapes, of fine flavor and taste.”

For many wine regions, the first wine harvest is lost in the mists of time, but South Africa knows its birthday. Jan van Riebeeck recorded the event in his journal on February 2, 1659. He had a particular interest in the success of the wine, since planting vines seems to have been his idea in the first place. Van Riebeeck had arrived at the Cape of Good Hope on April 6, 1652 on the Dromedaris, one of three ships. The journey had taken four months and had not been easy; the two other ships in the convoy, the Walvisch and the Oliphant, arrived the following day, after illness on board delayed them and cost a number of lives. The settlers in their entirety amounted to 90 people. As the commander of the new Colony, Van Riebeeck’s task was to establish a refreshment station that would assist the ships of the Dutch East India Company (the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) on their journeys back and forth from Holland to Batavia, in what is now Indonesia.

That passage itself was not new. Bartolomeu Dias had rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, proving that sailing around the southern tip of Africa was possible and opening the door to the maritime spice route. He named the Cape “Cabo das Tormentas”, or “Cape of Storms”, for the wind and rain that plagued wintertime passages. In what may be the most brazen act of geographical false advertising since Erik the Red returned with tales of “Greenland”, Portuguese King John II rebranded

to the Cape as a VOC employee. This Marieau, too, is reputed to be knowledgeable about winemaking, but nothing more is known about him.

Van der Stel expanded the European footprint in the Cape dramatically. Under his predecessors, vrijburghers had been confined to areas within a day’s ride of the Castle of Good Hope, at the edge of the water in Table Bay. The year he arrived he scouted out the inland areas for their farming potential, and after camping along the Erste River, decided it would be a suitable spot for a town. He even named it after himself; Stellenbosch means “Van der Stel’s woods”. By 1683 30 families were living there, and Van der Stel’s “City of Oaks” was officially designated as a town in 1685. Within two years, settlers would penetrate further inland to the Drakenstein Valley, encompassing what is today Franschhoek, Paarl, and Wellington.

In 1685, French religious politics drove a new group of settlers toward the Cape when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes. The edict, in place for almost a century, had forbidden religious persecution; with its termination, Huguenot minorities found themselves looking for friendlier places to call home, and many fled to the Dutch Republic. The Dutch, being of similar, Protestant faith, were welcoming, but were eager to find permanent homes for the emigrants elsewhere. In November of 1687 the Lords Seventeen sent Van der Stel a letter informing him that new settlers were on their way; a group of 138 French refugees arrived the following year, and 20 more the next. By 1692, 201 Huguenots had arrived, making up almost a quarter of the vrijburgher population. Huguenots continued to trickle in until 1720. Most were granted plots of land in the Drakenstein Valley, either in Wagonmakersvallej (Wellington) or Olifantshoek (Elephant Corner). The latter eventually became known by its current name, Franschhoek, or “French Corner”. The typical arrangement at the time allocated a farmer a 60 morgen (approximately 51 hectares) plot, on the condition that he cultivate it within three years.

It’s generally assumed that the arrival of the French raised the bar for winemaking in the Cape. Certainly the Lords Seventeen thought they would be of help; in the letter notifying Van der Stel of their impending arrival, they noted that, “Among them you will find wine-growers, and some of them who understand the making of brandy and vinegar, by which means we expect that you will find the want of which you complain in this respect satisfied.” For his part, Van der Stel was

unimpressed, at least at first. In 1689 he requested that the VOC not send any more Frenchmen, especially “people of quality” who were afraid of getting their hands dirty. Those who came from wine-growing regions seem to have seen success producing wine in the Cape; however, it doesn’t seem that their knowledge necessarily rubbed off on others, French or Dutch. Several Huguenots concentrated on wine growing very soon after their arrival. Pierre Joubert, originally from Provence, eventually owned several farms in Franschhoek including La Motte, La Provence, L’Ormarins, and Bellingham. Similarly, figures like Jacques Malan, the Villiers brothers, and Francois Retief would each go on to own multiple wine farms; their surnames, too, reverberate through the wine industry even today.

At the same time the Dutch vrijburghers, who had initially been reluctant to plant vines during Van Riebeeck’s day, came to so embrace wine growing that Van der Stel had to put limits on plantings. For every morgen of vineyard, he required a farmer to plant six morgens of wheat or other crops. He also worked to improve wine quality, fining those who harvested too early or worked with dirty barrels. In his memoirs, C.W. Kohler, the founder of the KWV, cited the vrijburghers’ enthusiasm as the first example of the overproduction that became such a problem for the industry later. He even speculated that the absolutist, mercantile system of the 1600s was ultimately better equipped to

The classic, Cape Dutch gable of Schoongezicht Manor House at Rustenberg

in 2018. The story of the estate’s rise and fall would make a book on its own. Mark Solms, a South African neurosurgeon living in London, had purchased the property in 2000. He undertook huge investments in the property, the workers living on the estate, and the community, eventually bringing in his friend Richard Astor as an additional investor. Housing, education, and a host of other post-apartheid issues were addressed, and the project was moving from one-third to one-half worker ownership when it collapsed. Big ambitions, failure to build sufficient export markets, and at the very least confusion about the nature and amount of government support the project would receive all led to liquidation proceedings.

Coming to wine from the outside

While worker-owned models like ESS attempt to rectify the ownership balance among those already in the wine industry, there are also a

A member of Fairview’s vineyard team at work

number of black or coloured businesspeople who have had some success in other fields before entering the wine industry, typically by purchasing a wine farm. In 2002 Malmsey and Diale Rangaka founded M’hudi, the first black-owned and family-operated winery in South Africa. Both were clinical psychologists with no agricultural background when they started the project. Their neighbors at Villiera mentored them, advising on viticulture and urging them to create their own brand rather than selling wine in the bulk market. They also helped them source grapes from farms elsewhere in the Cape so they could diversify their offerings.

Other black-owned brands have eased their entry into the industry by avoiding capital-intensive land purchases, at least at the beginning. Seven Sisters launched in 2007 as a virtual winery, buying and bottling bulk wine to create their own range. Vivian Kleynhans, one of the sisters and a former owner of a recruitment company, leads the project. One of the founding principles of Seven Sisters was to create a network among women from disadvantaged groups in particular. While the initial supply model for Seven Sisters relied on purchased bulk wine, Kleynhans pushed for greater control of production. In 2009 an LRAD grant allowed the company to purchase an 8.7-hectare property in Stellenbosch. They have since planted their own vines and built a tasting room to enable them to tap into direct sales rather than relying on distribution. In 2016 they launched the Brutus Family Reserve line, their first wines to include grapes from their own vineyards.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, wine drinking was not common in black communities during the latter decades of apartheid, especially outside the Western Cape. The resulting lack of a wine culture is another reason potential black investors might look elsewhere. It has also inhibited the development of black winemaking talent. However, a small but increasing number of black and coloured winemaker-owners are appearing, many of them women. Ntsiki Biyela’s profile rose dramatically when she launched her own brand, Aslina, in 2013 after several years as winemaker at Stellekaya. Brought up by her grandmother in KwaZulu-Natal, in 1999 she received a South African Airways bursary to study wine at the University of Stellenbosch, despite having never tasted wine. “It could have been anything,” says Biyela. “I wanted to study and I wanted to change my life.” In fact, only after she was accepted did she realize what she would be studying. Today Biyela sources from several vineyards around Stellenbosch and other areas and vinifies her wines at a custom

a number of social and athletic clubs. The choir is popular, as is netball, and more surprisingly, the karate club, which has actually represented South Africa at competitions overseas. Lack of social services is one of the biggest challenges facing many farms. Public transport is woefully undeveloped, so often the Fairtrade premium helps bring services and opportunities to the farms directly. Workers in the past might lose a whole day’s work for a simple doctor’s visit, but with an on-site clinic they can receive everyday treatment before or after their shift. Opportunities for leisure activities also cut down on social problems such as alcoholism.

The organizations behind Fairtrade had to adapt its model somewhat to accommodate social and political realities in South Africa. In other industries where Fairtrade is prominent such as coffee and chocolate, farmers generally work for themselves, whereas in the wine industry –not just in South Africa – the vast majority of labor is hired employees. For a time Fairtrade adopted the BEE scorecard as a means to evaluate a business’s qualifications for certification, but that was dropped in 2010. In part this was due to the explicitly racial goals of BEE; Fairtrade is also active in the South American wine industry, where similar income inequities exist, but the racial divisions are less glaring. Certification in South Africa does still require 25 percent black ownership. More recently, Fairtrade has begun allowing up to 20 percent of the premium to

Funded by Fairtrade premiums, the karate club at Bosman has represented South Africa in international competitions

be distributed directly to workers instead of being devoted to development programs. It’s hoped that this will assist in ensuring a living wage for workers.

The biggest deterrent preventing more producers from pursuing Fairtrade certification is the expense. Fairtrade is costly, and by some estimates more than half of the premium goes to the certifying organization rather than into the community. Farmers often find the auditing process onerous as well. For the brand, it adds to the retail price without a corresponding increase in wine quality, so it relies on the consumer’s interest in supporting ethical trade overriding their desire to get the best value for money. This has been harder to market in the world of wine compared to Fairtrade’s success with coffee and chocolate, perhaps because wine marketing is so lifestyle driven. Messages about poverty and social injustice seem jarring alongside the images of grand manor houses, luxury, and “gentleman farmers” that dominate wine marketing. That may be changing in some markets, but at least within South Africa wine drinkers have shown little interest to date.

About 5 percent of South Africa’s wines are now Fairtrade certified, representing more than 2,500 workers over 70 farms; by one estimate 11,500 people are experiencing improved living conditions due to the return on Fairtrade premiums. Individual producers have found benefits in the certification, especially when the industry faces negative publicity. Despite its successes, it became clear that a more universal, and more affordable, program was called for. In 2002 the industry began a decade-long process to create its own certification system, modeled on the already established IPW sustainability program. The goal was to have buy-in from all parts of the industry; 50 percent of board members are from labor unions. The result is the Wine Industry Ethical Trade Association (WIETA).

WIETA’s goals are not dissimilar to those of Fairtrade. The fees for certification are much more affordable, and there is no per-bottle premium. So certification provides documented evidence that a brand is operating ethically, but does not have as explicit a mechanism as Fairtrade to direct money from sales back into community development beyond the certification’s requirements themselves. For several years businesses paid a flat rate of 500 rand for their certification, but in 2019 WIETA introduced a scaled rate based on business size.

WIETA certification audits review a wide swath of potential problem areas including child labour, freedom of association, a healthy, safe

Kruger is a lawyer by training, and a self-taught viticulturalist. On repeated visits to France, she had seen the value and emphasis some growers there put on “vieilles vignes” – old vines. Grapes from old vine vineyards commanded a premium, as did wines made from them. Didier Dageneau, whom Kruger had the chance to work with, spoke glowingly of the virtues of old vines. Curious to see whether South Africa’s old vines would perform similarly, and command similar, higher prices, in 2002 she began to seek them out. At first, it was a hobby. While KWV had detailed records dating back to the beginning of the twentieth century, these were confidential, and Kruger relied on wordof-mouth to find the vineyards. There was no lack of such vines, especially among white wine varieties. Old vine red vineyards were, and still are, less common.

At the time, the production of these vines disappeared into coop blends or other larger production wines; in fact, much of it still does. Some winemakers were making remarkable wine from old vine vineyards, but they weren’t labeling the wines as such. Marc Kent, at Boekenhoutskloof, was sourcing grapes from century-old vineyards in Franschhoek, for example. Many of the vineyards were on multi-use farms, so the owners might not be relying solely on their vineyard income to survive. Many were in more obscure, outlying areas as well. Wine growers in places like Stellenbosch might be more financially driven; farming costs are higher, so the moment a vineyard there is sufficiently old that its production starts to flag, replanting begins. Kruger says some vines may have remained in the ground for sentimental reasons, or because the cost of replanting didn’t seem worthwhile. But in Kruger’s opinion, in many cases a winemaker begged the grower to leave them because of the quality of the wines they produced.

Hoping to demonstrate that quality explicitly, Kruger turned to Eben Sadie and her employer, Anthonij Rupert. Fortunately, their first wines, made with fruit from the Skurfberg, on Citrusdal Mountain, were remarkable, amply supporting Kruger’s thesis. As her search expanded, Kruger found herself playing a matchmaker role that directly addressed the challenges facing the Cape’s wine farmers. Locating and documenting old vine vineyards doesn’t in and of itself make them financially sustainable. Kruger introduced the owners of the vineyards to winemakers who were willing to pay well above the going rate for these grapes. This removed the grapes from the commodity market; low yields are financially sustainable if the price per ton is several times the going rate.

André Morgenthal, who joined the project in 2016, says these cellars are paying anywhere from 8,000 to 20,000 rand per ton for old vine grapes that went for 2 to 4,000 rand per ton previously. These differences can have huge significance to the farmer, who will ultimately decide whether a vineyard stays or goes. “The Old Vine Project is designed to make the vineyard sustainable and profitable for the farmer,” Kruger says.

Building on the high-quality wines and the publicity received, in 2014 Kruger went back to SAWIS, asking once more for access to planting records, which SAWIS had inherited from KWV. This time they agreed, with some stipulations. Kruger is required to get permission from the individual farmers before publishing any of the information. In addition, she personally is not allowed to profit from the information or draw a salary from the Old Vine Project. For funding, Kruger turned to her former employer, Anthonij Rupert. Rupert had supported Kruger’s efforts for several years, but in 2016 he underwrote the project formally so it could become a sustainable, non-profit organization. Morgenthal, former Director of Communications at WOSA, came on board as project manager. Going forward, the project hopes to become self-sufficient via membership fees and sponsorships.

In South Africa, as in other winegrowing areas of the world, “old vines” is not a protected term. Producers like Ken Forrester, Bruwer Raats, and others use it on their labels, without any affiliation with the Old Vine Project. However, in 2018 the project introduced the Certified Heritage Vineyards seal. Member producers can include the seal on their capsule or label; it confirms the sourcing and the year the vineyard was planted. Vines must be at least thirty-five years old to qualify; based on the project’s research, at that point vines have adapted to their environment, yields begin to drop, and other traits associated with old vines begin to appear. Thirty-five has become the accepted minimum age in practice more broadly as well. The seal has received international attention; Morgenthal has met with representatives from Australia, Napa Valley, and other wine-growing regions to discuss the program and its implementation.

As of 2019 the project has 1,377 qualified plots on its registry, encompassing 3,197 hectares of vines. Ten vineyards are over 100 years old; the majority date back to the 1960s and ’70s. Most are dry farmed. While many well-known examples are in outlying, less-familiar growing regions, Paarl and Stellenbosch have the greatest number of old vines, with 848 and 801 hectares respectively. Swartland is strongly associated

moved the vines when he felt they were ready, grafting them onto rootstocks in 1932 or 1935. Around this time Theron and Perold together christened the variety, creating a portmanteau of Pinot Noir and Hermitage, as Cinsault was known at the time, to arrive at Pinotage. Apparently “Herminot” was considered, but not adopted, to, one imagines, the eventual disappointment of Harry Potter fans.

Perold passed away on December 11, 1941, the same year that C. T. de Waal first vinified a wine from Pinotage. The first recorded commercial plantings were at Myrtle Grove (Now Rozendal) in 1943, but there may have been Pinotage vines at Kanonkop as early as 1939. Confirmed plantings followed at Uiterwyk in 1950, and Bellevue and Kanonkop in 1953. The latter still supply vines for the estate’s Black Label wine. In 1959 a wine made from Bellevue’s Pinotage vines won best wine at the Cape Young Wine Show; SFW bought up the wine, and released it

An old bush vine of Pinotage at Kanonkop

in 1961 as the world’s first commercial Pinotage bottling, the Lanzerac Pinotage 1959. In 1961 Kanonkop’s Pinotage won the same award, and it, too, became part of the Lanzerac wine until Kanonkop began bottling the wine under their own name in 1973.

The success of these farms led to expanded plantings. In accordance with the demands of the day, Pinotage could manage higher yields, at least for simple wines. It also ripens earlier than other red varieties, easing logistical pressures in the winery during harvest. By 1974 it made up 1.7 percent of the Cape’s plantings; a meager amount but significant within the then small world of South African red wines. Cabernet Sauvignon was only at 2 percent at the time, and only Cinsault had a really substantial presence.

A few years later the grape took its first knock when Michael Broadbent, visiting the Cape with a group of Masters of Wine from the U.K., declared that Pinotage smelled like “rusty nails”. Wine farmers remained undeterred, and Pinotage plantings held relatively steady for more than a decade. In 1991, Pinotage received a strongly contrasting second opinion when the Kanonkop 1989 won winemaker Beyers Truter the Winemaker of the Year award at the International Wine & Spirit Competition. Just as sanctions were falling and South African producers were hungrily eyeing the great export markets of the world, that world gave Pinotage a big thumbs up.

Plantings expanded rapidly in the 1990s, peaking in 2001 at 7.3 percent of plantings, where it is today. But its reputation, particularly in the U.S., has suffered. Too many of the wines pushed on receptive export markets in the post-embargo years had not been up to snuff. Other varieties faced difficulties as well; the South African wine industry was going through huge changes, fracturing and re-forming as producers adapted to new market demand. To some extent, Pinotage “took one for the team” by bearing the brunt of the approbation. Some critics and sommeliers have turned their back on the grape entirely. Lettie Teague, the wine columnist for the Wall Street Journal, still states in her bio that she “has never had a good Pinotage”. But the dust has largely settled. At home in South Africa, some winemakers still choose to ignore the grape; a few, to deride it. A significant number have embraced it, and have clearly demonstrated its potential as a high-quality wine grape.

Viticultural and winemaking approaches for classic wine varieties are well established, and often only need to be adapted to local conditions; with new varieties like Pinotage, it can take a long time for winemakers

Male in the 1920s, it seems to have been responsible for notable red wines in the Cape since Simon van der Stel’s days, and commanded top prices in the second half of the eighteenth century. While once used to produce deeply colored fortified wines, it began to decline when Hermitage (Cinsault) became popular. Unlike the grape that pushed it out, its yields are quite low. In addition, it seems to have had a difficult time with some of the early American rootstocks.

wine sTYLes

Sparkling wines

South Africa is the first New World country to develop a designation for its traditional method sparkling wines that does not ride the coattails of Champagne. Today, Methode Cap Classique, or, more informally, MCC, is the fastest growing wine category in the country, doubling every five years. Not only is quality very high, especially in relation to price; bubbly is also more profitable for the country’s struggling wine growers. They can typically pick grapes for these wines earlier, pulling the maximum output from the vineyard when waiting longer might cost up to 10 percent in crop volume due to dehydration.

The history of sparkling wine production in South Africa is not a long one. The first example came from Frans Malan at Simonsig in 1971 (there are occasional mentions of “Champagne” earlier, and there were definitely sparkling wines of some sort, but there’s no evidence these were methode champenoise wines). In 1935 the so-called Crayfish Agreement with the French had forbidden the use of French wine terms on labels. Consequently, Simonsig called the wine “Kaapse Vonkel” – “Cape bubbles” in Afrikaans, expecting that this would become the accepted name for the category. Simonsig and other estate producers were largely unconcerned with the export market at the time, so an Afrikaans name seemed reasonably marketable. Simonsig became more serious about bubbly production in 1978; Villiera and Boschendal followed, using the term methode champenoise, which they considered a description of the technique and not a geographical reference. By the time the French protested, more than a dozen producers were using the term. Export markets were just beginning to open when, in 1992, the Cap Classique Producers Association formed. South Africa’s bubblies gained a more marketable, romantic,

and French name that also avoided the use of any protected French wine words.

Today the Association owns the trademark to the name, but one does not have to be a member to use it on the label. There are over 200 producers making Methode Cap Classique wines, although many do so only in small amounts for wine club members, tasting room sales, and so forth. Pieter Ferreira of Graham Beck estimates total production to be approximately 7.7 million bottles. As of 2021 using the designation will require 12 months of lees aging; association members are already adhering to that minimum, but changing the actual regulations has dragged on, so for now the legal requirement on the books is only nine months. Beyond that, prerequisites are fairly barebones: wines must contain at least three bars of pressure, and must go to market in the same bottle that the second fermentation occurred in. The association recommends the traditional Champagne varieties Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier, but other varieties are permitted. Several producers are making Chenin Blanc-based examples, and Pinotage makes an appearance in some examples such as Simonsig’s Brut Rosé. Growth has presented challenges for the Cap Classique category. With many producers making bubbly but not specializing in it, some are concerned about consistency within the category. The Cap Classique

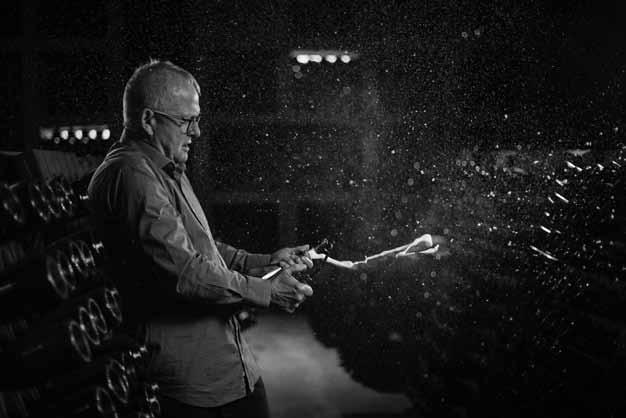

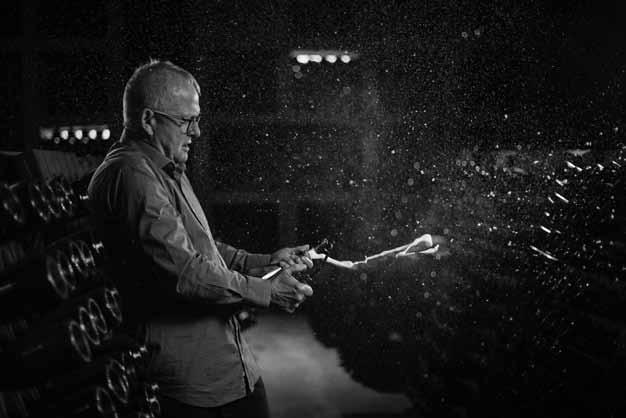

Pieter Ferreira, cellarmaster at Graham Beck

Terrain REGION District (*uno cial) Ward

Raithby

Stellenbosch

Elgin

Overberg

Overberg

Paarl

Breedekloof

Worcester

Cape Town

Klapmuts

Villiersdorp

Helderstroom

Franschhoek

False Bay

Stellenbosch

Franschhoek

Helderberg

Stellenboschkloo

Bottelary Devon Valley

Papegaaiberg

Simonsberg-Stellenbosch

Banghoek

Jonkershoek Valley

Pniel

Hilly Mountainous

7 sTeLLenBosch

In terms of infrastructure, market presence, and tourism, Stellenbosch is the center of today’s South African wine industry. Wine and the University of Stellenbosch are the two defining businesses in town, and more so than anywhere else in the Cape, the fields of Stellenbosch are almost a monoculture of grapevines. The district is home to 168 private wine cellars – the greatest concentration in South Africa – and more than 15,000 hectares of vines, planted in a relatively compact area. It’s an open question whether that density of plantings will endure. Stellenbosch is home to both the greatest and most troublesome trends of the South African wine scene; world-class wines come from the same vineyards that struggle with urbanization pressures and low prices.

Simon van der Stel conceived his namesake town, the second in the Cape Colony’s history, on November 6, 1679. Having just taken up his post as Commander of the Cape Colony, he embarked on a gettingto-know-you tour of his new territory. Encamped alongside the Erste River, he declared he would found a town there. Van der Stel opened up the area to vrijburghers the following year; eight families settled there. Three years later that had expanded to 30 families, and within ten years 48 families were farming more than 233,000 grapevines. Many of Stellenbosch’s famous estates from this time are still operating: Rustenberg, Rust en Vrede, Meerlust, and others all date from this era. The town itself, known as Eikestad or the “City of Oaks”, is also remarkably well-preserved, with ample examples of Cape Dutch architecture.

During the middle of the nineteenth century Stellenbosch, together with Paarl, was the center of wine production in terms of both quality and volume. That began to change as the railroad opened up the interior.

less structured barrels that suit early drinking. The wines overall are less polished and powerful than the De Trafford wines, but no less complex or expressive.

Delaire Graff Delaire.co.za

This Banghoek estate dates to John Platter’s purchase of the farm in 1982, two years after he and his wife Erica founded their now-famous wine guide. Platter named the farm Delaire (“from the sky”) in acknowledgment of the site’s amazing views. Diamond magnate Laurence Graff bought the property in 2003 and transformed it into a Relais & Châteaux property with accommodation, an art collection, and two highly-regarded restaurants. He also installed a state of the art cellar and in 2009 hired CWG member Morné Vrey as winemaker. The estate is planted with 20 hectares of Bordeaux varieties and Chardonnay, and the portfolio is a mix of estate wines and wines sourced more broadly; mostly Stellenbosch aside from their Chenin Blanc which is sourced from the Swartland. Aside from several varietal wines, including a trio of Chardonnays, the Cabernet Sauvignon-led Botmaskop, named for the peak behind the estate, and the Cabernet Franc-led estate wine “The Banghoek”, are the flagships.

Botmaskop Peak, in the Helshoogte Pass, Banhoek

DeMorgenzon

demorgenzon.com

With vineyards stretching from 200 to 400 meters up the east side of a hill in the Stellenboschkloof, this estate’s name, translating as “the morning sun”, sums up a lot about the exposures of its vineyards. Wendy and Hylton Appelbaum purchased the farm in 2003 and replanted many of the vineyards, allowing a few spots of old vines to persist; today the estate is home to 55 hectares of vines. Wendy is one of South Africa’s most prominent women, extremely wealthy and an active philanthropist, putting her time, money and legal background into efforts to protect workers and address women’s issues. Hylton is one of South Africa’s major classical music promoters, an interest that extends into the vineyards as well. Citing research that appropriate music encourages balanced growth in plants, he has installed a sound system to play Baroque music in the vineyards and cellar, with one amusing caveat: no harpsichord. The instrument figures prominently in Baroque music, but workers found its timbre too grating to endure for long periods. On the more conventional side of winemaking, Carl van der Merwe ran the cellar from 2010 to 2020, reducing the use of new oak, and in the whites, carefully managing malolactic fermentation to promote freshness and focus while still allowing generosity in the wines. Rhône varieties receive more attention here than is typical in Stellenbosch. The top-end Maestro line consists of three blends: a Rhône-style wine, a left bank blend, and an unusual white, with Roussanne leading supported by Chardonnay and Chenin Blanc. The Reserve range is the core of production. One red, a Syrah, is accompanied by a Chardonnay and an old vine Chenin Blanc, sourced from vineyards planted in 1972. With Van der Merwe’s departure in 2020, Adam Mason, formerly at Mulderbosch, is taking over in the cellar.

Distell

distell.co.za

Distell is South Africa’s largest wine producer, responsible for over 30 percent of production. Much of that is sourced from co-ops and then sold under a wide range of brands, but the company is nonetheless responsible for creating or managing some of South Africa’s legendary names. In the past many of their top brands have been handled as a separate portfolio, first under the Cape Legends banner, and from 2019–20 as Libertas Vineyards, but currently they are all under the Distell

Paarl 183

Stellenbosch 143–4, 176

van der Stel, Willem Adriaan 15, 144, 178–9, 223

van der Westhuizen, Bertho 156

van der Westhuizen, Lourens 236

van Goens, Rijckloff 14

van Heerden, Matthew 102

van Huyssteen, Nick 225

van Kempen, Jacob Cloete 9

Van Loggerenberg 178

van Loggerenberg, Lukas 178, 275

Van Loveren 42, 59, 84, 240–1

van Loveren, Christina 241

van Rensburg, Andre 108, 179

van Rheede tot Drakenstein, Hendrik 14

van Riebeeck, Jan 7–10, 16, 100, 102, 109, 209

van Vuuren, Gerrit Jansz and Suzanne 200

van Wyk, Rudger 177

Van Zyl family 114, 228

Veller, Bernard and Peta 141

Verburg 257

Verburg, Niels and Penny 259

Verdelho 177, 217, 243–4, 260

Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie see VOC

Vergelegen 15, 35, 108, 144, 178–80

Veritas 81

Vilafonté 99, 186, 193

Villard Blanc 274–5

Villiera 45, 122

Villiers family 13, 203

Villiersdorp Co-op 257

Vine Improvement Board 34

Vineyards Protection Act (1880) 20

Vinimark 172, 202

VinPro 35, 37, 47–8, 57–8, 60–1, 74, 78

Vintners Surf Classic 280

Viognier 110, 121

Breede River Valley 236–7

Cape South Coast 255, 260

Cape Town 135

Darling 220

Northern Cape 275

Paarl 185–6, 188

Stellenbosch 153, 160, 164, 177

Swartland 217

Tulbagh 225–6

Wellington 196

Virgin Earth 242

Vititec 108

Vlok, Conrad 271

VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) 7–18, 131, 144, 179, 256

Voor-Paardeberg 70, 105, 185, 260

Vrede 258, 268

Vredendal 227

Vrey, Morné 154

Vriesenhof 46, 180–1

vrijburghers 10, 12–18, 94, 138, 143–4, 183

Vuurberg 217

Wagenaar, Zacharias 10

Wahl, Pierre 225

Waibel, Dieter 134

Walker Bay 119, 172, 256–68 map 253

Wallace, Robert 30–1

wards, Wine of Origin scheme 72

Warwick 110, 181, 193, 280

Washington, George 132 water 94–6 licenses 74 see also irrigation; rain

Waterford 145, 181–2

Waveren 225

Webb, Gyles 36, 48, 146, 177–8, 207

Webb, Thomas 177

Weerts, Graham 239

Welgegund 225

Welgemeend 111

Wellington 12, 34, 42–3, 94, 112, 119, 126, 194–6 map 184

Wellington, Duke of 132, 194

Weltevrede 235

Wentzel, Jacques 201

West Coast 229 map 222

Western Cape 70, 73 map 71

whale watching 262, 266, 280

Whitehall Farm 249

Whole Bunch, The 80

wholesalers 69

Wiehe, Mark 166

Wieser, Johann Daniel 18

Wildekrans 257

Williams, Chris 159–60

winds 91–4

Breede River Valley 235

Cape South Coast 247–8, 254, 257, 269

Cape Town 133–4, 138

Franschhoek 198

Paarl 185

Stellenbosch 144

Wine and Brandy Control Act (1924) 24–5

Wine and Spirits Board 70, 72, 77, 153

Wine and Spirits Control Acts (1940, 1954) 26–7, 37

Wine Education Trust 48

Wine Industry Development Company (DevCo) 37

Wine Industry Ethical Trade Association (WIETA) 47, 55–7

Wine Industry Transformation Charter 40

Wine Magazine 80–1

Wine of Origin scheme 29–30, 59, 70–5, 113

Cape Coastal 249

Cape Town 129, 141

Coastal Region 201

Franschhoek 197

Klein Karoo 242

Malan 175

Overberg 252

Robertson 236

Swartland 212

Western Cape 4, 192, 249

wine routes 144, 175, 185, 278

Wine Training South Africa 47

Wines of South Africa (WOSA) 1–3, 78, 80

Winetech 35, 78

Winshaw, William Charles 156

Wolvaart, Philippus 157

Women in Wine program 162

Woolworths 46

Worcester 20, 26, 61, 96, 105, 231, 233–4

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) 77

Wraith, Mark and Monica 164

Wynberg 10, 21, 132

Xinomavro 219

yields 58–60

Young Wine Show 29, 116–17, 188, 207

Zandvliet Wine Estate 241

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa 280

Zevenwacht 170

Zimbabwe 22

Zonnebloem 48, 103, 158

Zoo Cru 80, 214–15

Zuma, Jacob 3