THE ROOTS OF WINE

Records of human habitation on the Atlantic seaboard of the Iberian Peninsula date back to the Paleolithic period, towards the end of the last glaciation. The sheet of ice which covered Great Britain and mainland Northern Europe did not reach Portugal, and the discovery in 1992 of a series of remarkable engravings in the schist of the Coa valley confirms that the north of Portugal was inhabited by nomadic hunting people at least 26,000 years ago. As the climate became warmer, the population moved towards a more maritime existence and during the Mesolithic period the people of western Iberia lived around the estuaries of the great rivers that flow into the Atlantic, especially the lower reaches of the Tagus.

The peoples of the Iberian Peninsula seem to have remained in total isolation until the Neolithic (3,000–5,000 years ago) by which time the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt (known to be wine producers) were already well developed. It is at this stage that a distinct north–south cultural divide seems to emerge in western Iberia. During the first millennium before Christ, the north (extending from Galicia to the Mondego) became populated by Celts, who were engaged in iron-founding and shepherding as well as the cultivation of the valleys. Defensive settlements called castros were built on the hilltops and the names live on in towns like Castro Daire, Castro de Avelãs and Castro Laboreiro. South of the River Mondego the inhabitants of the Peninsula looked towards the Mediterranean. As early as 800 BC the Phoenicians established a trading post on the Atlantic promontory occupied today by Cadiz. They moved west into the southern part of Portugal but hardly ventured north of present-day Estremadura. The Algarve was certainly well colonized and the city of Ossonobra, near modern-day Faro, is thought to be of Phoenician origin.

Although vines may have been introduced to the Iberian Peninsula by the Tartesians as early as 2000 BC, it was almost certainly the Phoenicians who introduced winemaking to Portugal. It is therefore likely that the earliest commercial vineyards were established in the south of the country, possibly stretching as far north as the Rivers Sado and Tagus. The Romans reached Portugal around the turn of the second century BC. They refined considerably the tradition of winemaking, taking the vine further north as they fought off the tribal Celts and imposed their own civilization on central Portugal, the land they called Lusitania. Populations began to stabilize and by the first century BC

there is evidence that viticulture was being practised as far north as Conimbriga (the Roman settlement just south of modern-day Coimbra) and Trás-os-Montes (which includes the Douro). For a time in the first century AD the River Lima formed the northern frontier of Roman Lusitania. According to legend a horde of Celts had traversed the river and never returned. Junius Brutus thought that the Lima was the ‘River of Forgetfulness’ and his troops refused to cross. Eventually the Romans ventured north, over the River Minho and founded Callaecia (Galicia). By this time, viticulture was implanted in both the Douro and Alentejo. The Romans brought amphorae for making wine. The clay talhas (also known as anforas) that are currently undergoing a revival in the Alentejo are their direct descendants. A sarcophagus dated between the first and third century AD found near Reguengos de Monsaraz in the Alentejo (now in the Soares dos Reis Museum, Oporto) shows two young men dancing whilst treading grapes. Nearby Ebora (Évora) became an important Roman administrative centre.

Christianity reached Portugal during the second century AD and a number of cities began to emerge as centres of religious as well as political and economic significance. By the fourth century there were Bishoprics in Ossonobra (Faro), Ebora, Olissipo (Lisbon), Aquea Flaviea (Chaves) and Bracara (Braga). Wine was a vital part of the Christian rite and vineyards would have been planted in the countryside surrounding these cities which, in the main, corresponded to the old Roman municipia.

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire from the fifth century onwards the Iberian Peninsula was overrun by successive tribes of Suevi, Visigoths and Moors. The Suevi and Visigoths who occupied the north of modern-day Portugal continued to defend the Christian faith, establishing new dioceses at Pax Julia (Beja), Conimbria (Coimbra), Veseo (Viseu), Lamecum (Lamego), Tude (near the River Lima) and Portucale (Oporto). Trás-os-Montes and the mountains of the Beiras are punctured by small troughs known as pias or laragetas carved from the granite bedrock. Dating from this period, it is likely that they were used for producing both olive oil and wine.

In 711 Iberia was invaded by Muslims from the south and within five years most of the Peninsula had been conquered by Islam. Viticulture clearly suffered under Islamic rule although during the early part of the occupation, winemaking was tacitly permitted by the Emir of Cordoba, who governed Lusitania. Later rulers such as the Almoravids took a much more orthodox line and prohibited the production and trade of wine.

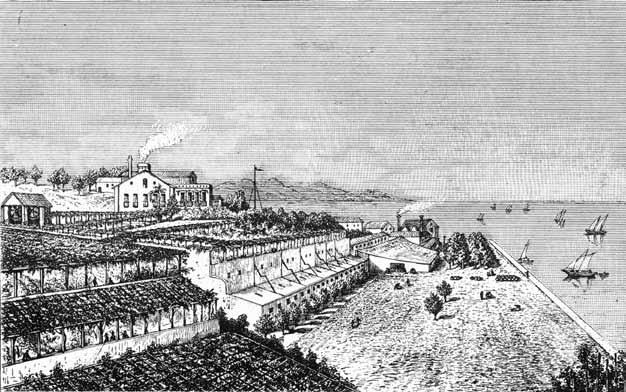

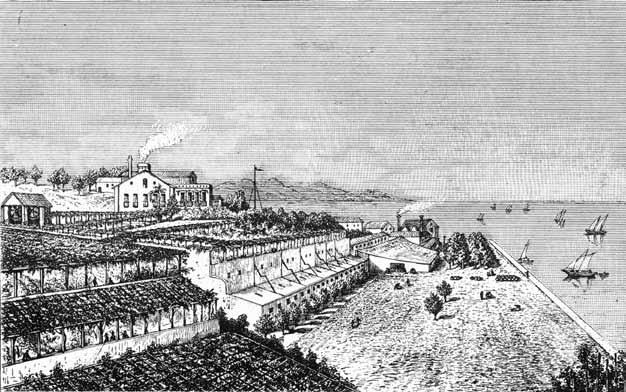

to be exported to Britain in large volumes. The wine shipping firm of Sandeman, established in both Oporto and Jerez in 1790, owned substantial cellars at Cabo Ruivo, on the Tagus just outside Lisbon. During the course of the century they were joined by other shippers including José Domingos Barreiros (producers of ‘Special Lisbon Wine’), Wynn and Custance and Abel Perreira da Fonseca, at both Lisbon and Torres Vedras, while on the south side of the river at Arealva (Almada) there was the Sociedade Vinicola Sul de Portugal Lda. (subsequently J. Serra) and José Maria da Fonseca, at Azeitão near Setúbal. No doubt helped greatly by the construction of the first stretch of railway from Lisbon to Carregado in 1856, the wine trade became a flourishing port-based industry with vineyards planted in the hinterland on the rolling hills around the city. There were vineyards within the city limits at Olivais and Sacavém as well as just outside at Frielas, Unhos and Tojal. These wines were commonly sold as ‘Camarate’, a locality now close to the end of the runway at Lisbon airport, which lent its name to a red wine described at the time as being ‘not dissimilar to the unfortified wines of the Douro’. Camarate is famous as the scene of a mysterious plane crash which killed Francisco Sá Carneio, the Portuguese Prime Minister, in 1980 and the name lives on as the name of a grape variety planted north of Lisbon. A new vineyard planted by the airport roundabout in 2015 contains a significant quantity of Camarate vines.

The adegas of Messrs. Sandeman Brothers at the Quinta de Cabo Ruivo, near Lisbon as illustrated in Henry Vizetelly’s Facts About Port and Madeira, 1880

Henry Vizetelly gives an idea of the range of wines produced in the Lisbon region when he describes a visit to the cellars of Wynn and Custance, shippers of wine to Russia, the Baltic and to a lesser extent Brazil and England. ‘Here’, he writes, ‘were deep-tinted Sacavém red wines, some of them dry and clean tasting, and others extremely sweet; a rich and potent Arinto from the same vineyards, the soil of which is darker and richer than in the Bucellas district; red Lisbons and white Lisbons – the former principally designed for the Brazilian market, while dry and rich varieties of the latter are shipped to England, the more luscious qualities – soft, sweet ladies’ wines – going cheifly to Russia and the Baltic.’ The wines of Carcavelos, fortified in the manner of a Sherry or Madeira, are described as ‘agreeable, with a pleasant nutty aroma; a much older wine had great body and a pronounced almondy flavour; while an even more ancient sample … powerful and concentrated had developed the characteristics of a fine old Madeira.’

Messrs. Wynn and custance’s adegas at Sacavem, near Lisbon as illustrated in Henry Vizetelly’s Facts About Port and Madeira, 1880

There were a number of sweet, fortified wines produced on the south bank of the Tagus, where Moscatel was planted around Azeitão and Palmela near Setúbal; the Bastardo grape grew at Lavradio near Barreiro (now an industrial suburb of Lisbon). In the 1870s Vizetelly describes vineyards that ‘extend almost from the shore for some half-a-dozen miles inland, occupying all the low sandy slopes and occasionally the

Underpinning DOC is an important category officially called Indicação Geográfica Protegida (IGP) or known more simply in Portugal as Vinho Regional (VR). This is equivalent in status to the French Vin de Pays or the Spanish Vino de la Tierra but has gained rather more significance as the rules are much less restrictive than for DOC, giving producers considerably more leeway. The entire country is divided into fourteen regions on a provincial basis (see Map 2, opposite). Winemakers are permitted to blend wines from anywhere within these regions and from a much longer list of grapes than permitted by the DOCs. Whereas many DOCs tend to limit themselves to native local varieties in an attempt to protect much-vaunted tipicidade (tipicity), the Vinhos Regionais permit all manner of grapes, including a large number of international varieties. They tend to be more important in the south of the country, where the DOCs are newer and traditions are not so ingrained as they are in north and central Portugal.

Finally, underpinning the system is a category common to every EU country; table wine or vinho de mesa. In Portugal, which is no different from anywhere else, the date of vintage, grape variety or geographic provenance is not permitted on the label of vinho de mesa which, apart from the name of the bottler and a brand name, is merely an anonymous blend. Many of the least expensive supermarket wines fall into this category but there are also some curiosities that occasionally fall outside the law.

The control of Portugal’s wine sector (with the exception of Port and Madeira) is the remit of the Instituto da Vinha e do Vinho (IVV). Based in Lisbon but with regional representation, the IVV’s responsibilities are wide-ranging. In its own words, the IVV is responsible for ‘participating in and accompanying the wine sector with the object of improving quality, reinforcing competitiveness at an international level as well as the sustainable development of viticulture and wine production’. It is also responsible for the Sistema Nacional Integrado de Informação da Vinha e do Vinho (i.e. information and statistics, including the national vineyard register), the collection of taxes from the sector and the coordination and application of measures to manage Portugal’s vineyard heritage. The Instituto dos Vinhos do Douro e Porto (IVDP) and Instituto do Vinho, do Bordado e do Artesanato da Madeira (IVBAM) operate independently under similar remits, the latter taking in embroidery and handicraft as well as wine. A list of the generic bodies responsible for controlling and promoting Portuguese wines can be found on page 338.

RioLima

LISBON Spain

Terras Madeirenses Atlantic Ocean Faro

Porto

Açores

Vouga Rio Douro RioAve

Duriense

Terras de Cister

Terras do Dão Beira

Lisboa Tejo

Alentejano

Algarve

Terras da Beira

Península de Setúbal

Coimbra

Map 2: Vinhos Regional (IGPs) of Portugal

almost certainly the same variety as Cainho Branco, which Cincinnato da Costa describes as being favoured by growers for its productivity and richness of sugar. He equates it with Alvarinho (which, stangely, does not warrant a separate entry in his book) and remarks that the grapes he was sent for analysis were from Quinta de Moreira. The variety is still known locally as Cainho de Moreira. In Spain it is known as Caiño Blanco.

Caracol

The charmingly named white ‘snail’ grape is only found on the island of Porto Santo. It was supposedly introduced to the island in the 1930s by a Portuguese emigrant to South Africa and planted at Eiras by José da Silva. Originally known as Uva de Eiras, it was later renamed Caracol as this was Senhor Silva’s nickname. It is cultivated as both a table and a wine grape and is authorized for the production of fortified Madeira wines.

Cercial/Cerceal (Cercial da Bairrada) */**

There is a certain amount of confusion surrounding this grape, planted throughout the Douro, Dão and Bairrada. It is worth stating that this is not the same as Sercial (p. 110), which grows on Madeira and is also found on the mainland growing under a number of different synonyms. It is thought that Cercial de Bairrada is a cross of Sercial and Malvasia Fina (p. 94). The IVV lists Cerceal and Cercial as two different grapes although this productive but late ripening variety seems to be much the same wherever it is planted. Although Cercial generally produces rather dull wines it is still valued in the Dão region where, on the slopes of the Serra d’Estrela around Gouveia, it contributes a certain freshness and liveliness to blends. In Bairrada, where it is sometimes blended successfully with Bical, Cercial is very sensitive to oidium, and the thin-skinned grapes are prone to rot. One authority recommends that it should be the first Bairrada grape to be harvested ‘or at the very least when it begins to rain’.

Recommended varietal wines

Campolargo, Cerceal (Bairrada)

Chardonnay ***

Although the grape has travelled the world from its native Burgundy it has made remarkably few inroads within Portugal. There is a smattering of experimental Chardonnay in almost every region but commercial

quantities are only found in the Tejo region and on the Setúbal Peninsula, the two regions that have been most strongly influenced by New World winemakers. Renowned for its adaptability, Chardonnay produces a full spectrum of aromas and flavours in Portugal, reflecting the diversity of terroir. In maritime areas like Bairrada and Estremadura it produces wines with a crisp, apple-like character, whereas on the Setúbal Peninsula it produces fat, rich wines of almost Australian proportions. In the Ribatejo where there is more Chardonnay than in any other region of Portugal, it seems to be stretched somewhat by consistently high yields, and in the Alentejo the climate appears to be too extreme for the variety to retain much in the way of balance or finesse. To date, the best site for Chardonnay in Portugal appears to be the more lofty vineyards above the Douro, where Real Companhia Velha has produced a wine that deservedly wins medals on the international stage. Much is down to skilful winemaking but I am assured that at an altitude of around 500 metres Chardonnay needs little or nothing in the way of acid adjustment (and it shows). Of course DOC Douro cannot be applied to Chardonnay, so the wine, like all the others in Portugal, belongs to the Vinho Regional category.

Recommended varietal wines

Real Companhia Velha, Quinta do Sidrô, Chardonnay (VR Duriense)

Códega

See Síria, p. 92

Códega do Larinho *

Often confused with Síria (which is sometimes called Códega), the Códega do Larinho grape grows in the Douro and Trás-os-Montes, producing fruity, floral wines with relatively low acidity. Usually found in blends with Rabigato (p. 95) and Gouveio (p. 99).

Crato Branco

See Síria, p. 92

Dedo da Dama

These elongated grapes known as ‘lady’s finger’ are frequently found on pergolas in the Douro, where they are much appreciated for the table. The berries have the shape of a long, well manicured fingernail.

increasingly outweighed by problems. After the phylloxera epidemic in the late nineteenth century, vine varieties were selected for their resistance to disease, vigour and yield rather than the intrinsic quality of their fruit. Vigorous plants (including many direct producers and hybrids) produced a heavy crop of grapes that were low in sugar and high in acidity.

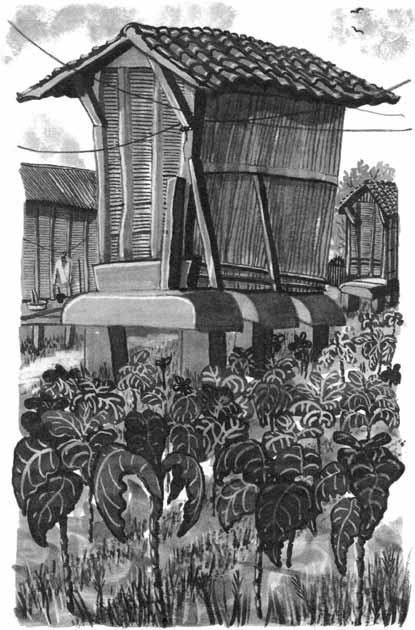

In the 1970s (with the relaxation in the ‘decorative’ legislation that followed the revolution) growers began to abandon the labour-intensive pergolas in favour of lower forms of training. This was the era of the cruzeta. In this system, four vines are planted around the base of a wooden, cement or granite pole, two metres or so in height. A crossbar (hence the name cruzeta) 1.5 to 1.8 metres in width supports two lateral wires along which the vine’s fruit-bearing arms are trained to give the plant a semblance of order and shape. Planted in rows and spaced to allow tractors to pass in between, cruzetas permit a certain amount

Vinho Verde: espigueros (granaries) and cabbages

of mechanization but they proved unpopular with growers, who find them troublesome and expensive to maintain. Most growers have now moved on to a more straightforward system of training, cordão simples, with vines supported on a vertical cordon 1.5 metres in height. This facilitates mechanization to the extent that some larger estates are now harvested by machine. Planted at a density of 2,000 vines per hectare (compared to the fewer than 500 vines per hectare common in the past), cordon planting has helped to improve the quality of the fruit. A focus on better varieties, along with increased exposure, has produced grapes with higher levels of sugar and lower acidity. Initially, when the maximum permitted level of alcohol for Vinho Verde was 11.5% abv, this brought some growers into conflict with the authorities.

Subregions

The Vinho Verde region divides into nine officially recognized subregions, each of which produces a distinct style of wine based on a different terroir and a different mix of grapes. Most of the Vinho Verde DOC is covered by these regions, with the exception of the area around Viana do Castelo, the city of Oporto and the area in the south bordering Lafões.

In the extreme north along the River Minho, Monção–Melgaço takes in the municipalities of the same name. This subregion is sufficiently well sheltered from the Atlantic to make it ideal for Alvarinho, the same grape as Albariño, which is cultivated in Rias Baixas in Galicia, immediately to the north. In fact growers here became so possessive about the Alvarinho grape that the authorities effectively prohibited it from being planted elsewhere in the Vinhos Verdes. However, in what could prove to be a game-changer for the region, from 2020 Alvarinho can be used to make Vinho Verde anywhere in the DOC. But the Monção–Melgaço subregion still has a dynamic all of its own and Alvarinho wines (technically categorized as Vinhos Verdes) enjoy a certain amount of autonomy from the rest of the region. Alvarinho typically ripens to produce wines with 12.5 or 13% abv, although the Trajadura grape is also planted in the region and the two varieties are sometimes blended to produce a distinctive but less fragrant style of wine. Two distinct styles of pure, varietal Alvarinho have emerged. Those from the stony, alluvial soils tend to be the richest and most aromatic whereas those from granite are more subdued. Although no distinction is made on the label, Alvarinho from Melgaço, upstream, tends to have more nervy acidity whereas that from Monção produces wine which is softer and more rounded. The

Alenquer

Sheltered from the Atlantic westerlies by the limestone hulk of the Serra de Montejunto, Alenquer paints a different picture from Torres Vedras, which lies over the hills but not so very far away. This is good fruit-growing country, seen as a prerequisite for producing good grapes and thereby good wine. It is no coincidence that some of Lisboa’s best wine producers are clustered around the quiet whitewashed town of Alenquer. Physically, the region is anything but uniform, with rolling limestone hills to the west and an alluvial plain stretching to the Tagus in the east, which is closer in character to the Tejo region than Lisboa. The region has three cooperatives, but two large private producers, Casa Santos Lima and DFJ Vinhos, have been doing most of the running in recent years (admittedly under the Lisboa VR rather than the local DOC). The traditional grape varieties in Alenquer are similar to those elsewhere in Lisboa: Arinto, Fernão Pires, Jampal and Vital for white wines and Castelão, Camarate, Trincadeira and Tinta Miuda for reds. Castelão, Trincadeira and Tinta Miuda are all capable of making quality wines if yields are kept in check but many producers have moved to planting grapes like Alvarinho, Chardonnay, Viognier, Aragonez, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Touriga Nacional, all of which feature in the list of permitted varieties. Just over 600 hectares qualify for DOC status. For many years the region was under threat from the construction of Lisbon’s new airport, which was due to be built at Ota, 10 kilometres north of Alenquer. This project has now been transferred to the other side of the Tejo at Montijo.

Arruda

The last piece in the complex jigsaw of DOC regions fits tightly in between Alenquer, Torres Vedras and Bucelas. It is named after the sleepy little town of Arruda dos Vinhos, where wine is so important that it is even embodied in the name. The surrounding hills, topped by windmills, are some of the most intensively cultivated in Portugal, yielding large quantities of grapes, with the bulk of wine made at the reasonably well-run local cooperative. Fortuitously for Arruda, but unusually for Lisboa, red wine predominates here, with Castelão, Camarate and Tinta Miuda the principal grapes. The wines rarely show the same class as those of Alenquer to the north but are light, peppery and early maturing. Arruda has therefore become the source of many a wine bottled under a proprietary label.

Producers

At the time of writing, the Rota dos Vinhos de Lisboa (a wine route that includes Bucelas, Colares and Carcavelos – see separate entries below) is undergoing revision. The producers asterisked (*) below are generally open to passing visitors.

Quinta do Carneiro

Alenquer www.quintadocarneiro.com

Situated on flat, fertile land close to the Tagus near Carregado, Quinta do Carneiro appears to belong to the Tejo rather than Lisboa region but is nevertheless just within the Alenquer DOC. The property has been completely restored since 1990 and the 42-hectare vineyard, planted with a wide range of grapes, is fully mechanized. With fertile alluvial soils, yields here are naturally high, reflected to a certain extent in the wines, some of which are on the light side, though all are fruit-driven and well made. The property has a huge range of grapes to choose from, all block planted: Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Alicante Bouschet, Touriga Nacional, Tinta Barroca, Tinta Roriz, Trincadeira and Castelão for the reds; Fernão Pires, Jampal, Arinto and Pinot Gris for the whites. Vinhas do Carneiro is the estate’s least expensive line; its most prestigious wine is Pactus, a dense, aromatic Touriga Nacional.

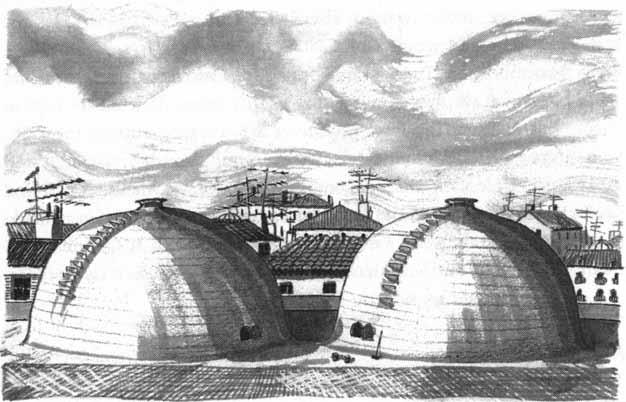

Lisboa: balões or mamas for bulk wine storage

on the leeward side. From 2,000 millimetres and more on the mountain peaks, annual rainfall diminishes sharply to as little as 400 millimetres per annum, perennial drought, along parts of the frontier with Spain. The planalto, or high plain in the farthest north-east corner of the country is really an extension of the meseta, although the word is never used in Portuguese, where it is known by the provincial name of Trás-os-Montes (‘behind the mountains’). This remote region, with its cold winters and hot summers, is sealed off from the Atlantic by a chain of granite serras reaching up to 1,500 metres in the Gerês. It has its own DOC, Trás-os-Montes and a Vinho Regional, Transmontano.

The Trás-os-Montes province ends at the River Douro, which cuts a chasm through the north of Portugal. Although it has never been a single administrative region, the upper Douro (or Douro Vinhateiro as it is sometimes called) has a strong territorial claim of its own. Where the river flows through the slate-like schist, the Douro and the lower reaches of its tributaries, the Corgo, Varosa, Távora, Torto, Pinhão, Tua, and Côa, collectively form one of the world’s most dramatic vineyard regions, demarcated both for Port (Vinho do Porto) and unfortified Douro wines.

The vineyards to the south of the Douro belong to the Beiras, a huge slice of central Portugal that splits into three. The land rises steeply into Beira Alta and although grapes for sparkling wines are grown on the so-called altos above Lamego, much of the country immediately south of the Douro is too high and too sheer, even for vines. The upper limit is about 900 metres above sea level. The DOC of Távora-Varosa, which covers the upper reaches of the Távora, Tedo, Varosa and Torto valleys, all of them tributaries of the Douro, is the first DOC in Portugal for sparkling wines (see page 227). Terras de Cister is the small Vinho Regional. The giant massif of the Serra de Estrela rises to a height of 1,993 metres (the highest point in mainland Portugal) and the land around the city of Guarda to the north-east is bleak, windswept and barren. The granite soils are frequently too poor and shallow to support viticulture but there are outcrops of schist on the planalto, north of Pinhel, where there is a cooperative and a handful of growers have proved that vines can be cultivated to good effect.

The Mondego, the largest river entirely within Portugal, bubbles up as a spring in the Serra de Estrela and loops round the northern flank of the mountains, carving a broad basin to the south of Viseu. This region takes its name not from the mighty Mondego but the diminutive River

Dão that rises near Trancoso and crashes over granite boulders until it joins the Mondego downstream from Santa Comba Dão. Hemmed in by mountains, Dão is in the middle of the Atlantic–continental climatic transition. It has traditionally been the repository of some of Portugal’s finest red wines which, after a half-a-century of decline, have been undergoing a timely revival.

East and south of the Serra de Estrela the watershed belongs to the Tagus or Tejo and the upper reaches of the River Zêzere define a basin known as Cova de Beira. This is the heart of Beira Baixa (lower Beira), a province that extends all the way down to the River Tagus, south of Castelo Branco. Cova de Beira is a good fruit-growing area that is slowly turning to growing grapes and producing wine. Much of the wine from this region is bottled under the Vinho Regional of Terras da Beira. There is also a DOC, Beira Interior, that now encompasses parts of Beira Alta and Beira Baixa.

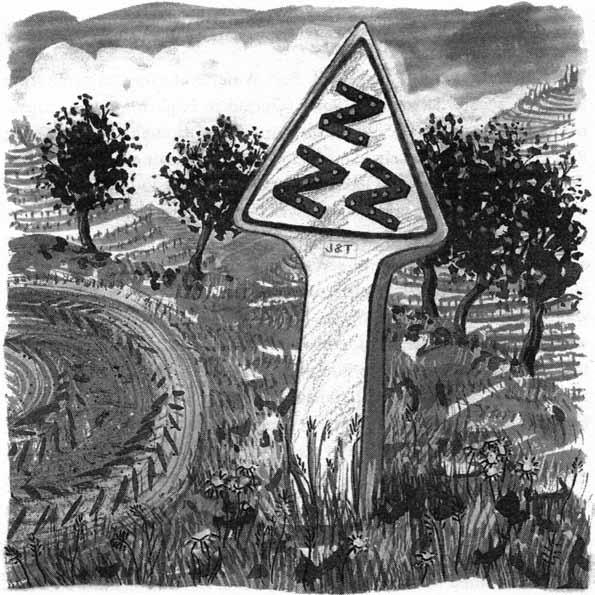

Lazy ‘z’ bends in the mountains of northern Portugal

Height in metres

1100–2000

600–1100

200–600

100–200 0–100

Atlantic

Ocean

Santo Tirso

Porto

Espinho

Aveiro

Oliveira do Bairro

Anadia Mealhada

Cantanhede

Figueira da Foz

Amarante

Penafiel

Vila Real

Baião Peso da Régua

Rio Douro

Castelo de Paiva

São Pedro do Sul

Mortágua

Viseu

Alijó

São João da Pesqueira

Lamego Vila Nova de Foz Côa

Trancoso

Penalva do Castelo Mangualde

Nelas Gouveia

Santa Comba Dão

Coimbra

Pombal

Leiria

Nazaré

Óbidos

Bombarral

Torres Vedras

Arruda dos Vinhos

Sintra

Lisbon

Oeiras

Cascais

Tomar

Alcobaça

Caldas da Rainha

Abrantes Torres Novas

Chamusca

Rio Maior Santarém

Cartaxo

Alenquer

Vila Franca de Xira Cadaval

o

Almeirim

Coruche

Seia

Covilhã

Fundão

Serra daMarofa

Pinhel

Ri o Cô a

Freixo de Espada à Cinta

Guarda

Castelo Branco

Castelo de Vide

Ponte de Sor

Avis

Portalegre

Estremoz

Arraiolos

Montijo

Almada

Serrada Arrábida

Sesimbra

Setúbal

Montemor-o-Novo

Alcácer do Sal

Grândola

Sines

Serra do Mendro Serrade Ossa

Évora

Reguengos de Monsaraz

Portel

Vidigueira

Beja

Castro Verde

Ourique Mértola

Campo Maior

Elvas

Borba

Redondo

Serpa Mourão Moura

Spain

Aljezur

Portimão Silves

Lagos

Albufeira

Faro

Tavira

Vila Real de Santo António

5 WINES OF THE PLAINS

The River Tagus rises in the mountains of central Spain, west of Guadalajara. For much of its 1,000-kilometre course, the river is an unreliable stream and, as the Tajo (meaning ‘cut’ or ‘gorge’), is not accorded great significance by the Spanish. By the time it reaches the Portuguese frontier, the river is in full flow and, as the Tejo, it takes on a new meaning. Cutting a diagonal through the centre of the country, the Tagus divides Portugal asymmetrically in two. The north, mountainous and densely populated, is counterbalanced by the more sparsely inhabited south, which is largely rolling plain.

In fact the plains of southern Portugal are not nearly so homogeneous as they sound. Although the landscape is not as stark or dramatic as that of the northern mountains, it has a grandeur transfigured by considerable variation in climate, geology and culture. From the shifting sands around the Tagus and Sado estuaries and the rolling, windswept countryside of the Alentejo littoral, to the solidity of the schist, granite and limestone of the Alentejo interior, southern Portugal has a diversity in landscape that is reflected in its ever-expanding range of wines.

Forty years ago it was another world entirely. Apart from the Setúbal Peninsula, the most maritime of the main wine regions, there was little of distinction to be had from either the Ribatejo (now known as Tejo) or Alentejo. Both regions were hampered by their climate. Away from the moderating influence of the Atlantic, the temperature is quite capable of exceeding 40°C – very occasionally approaching 50°C – during the summer months. With rainfall at best unreliable and often deficient for months on end, the vines shut down simply to ensure their survival. Although sunshine (which rises to over 3,000 hours per annum in the

among the cork forests at nearby Pizões. There are two vineyard nuclei, one just outside the fortified town of Moura itself and the other towards Serpa (a town famous for its ewe’s milk cheese). Just 32 hectares qualify for DOC so the name ‘Moura’ is almost never seen on labels. The climate is similar to that of Granja-Amareleja, immediately to the north but the calcareous clay soils are deeper and yields are consequently more abundant. Castelão has traditionally been the principal grape, supported by Trincadeira and Alfrocheiro, which together produce soft, rather sweet, jammy reds that reflect the hot climate. Figs and raisins are also important agricultural commodities. There is no cooperative in the area but the Encostas de Alqueva label is associated with the co-op at nearby Granja-Amareleja. A large estate called Casa Agricola Santos Jorge, now trading as Herdade dos Machados, is the principal producer.

Vidigueira

A low scarp, the Serra de Mendro, between Portel and Vidigueira, marks the physical boundary between the Alto and Baixo Alentejo. The town of Vidigueira was the home of Vasco da Gama, a fact celebrated in the local cooperative’s red wine called Vila dos Gamas. The country around Vidigueira is some of the hottest and most arid country in Portugal, with sweltering summer temperatures. It is surprising that so much of the region’s 2,600 hectares of vineyard is planted with white grapes, traditionally the rather lowly Diagalves, Manteúdo and Perrum, although Antão Vaz is the best performer. The cooperative makes a good varietal. However, red grapes have been on the increase, mostly Trincadeira and Alfrocheiro, although there is also a significant amount of a variety known as Tinta Grossa or ‘Tinta da Nossa’. Alfrocheiro seems to perform particularly well in Vidigueira’s relatively fertile clay-limestone soils. Most of the region’s wines are made at the local co-op, which also draws on fruit from the neighbouring municipalities of Cuba and Alvito, but there is an increasing number of promising estates located south and east of the town.

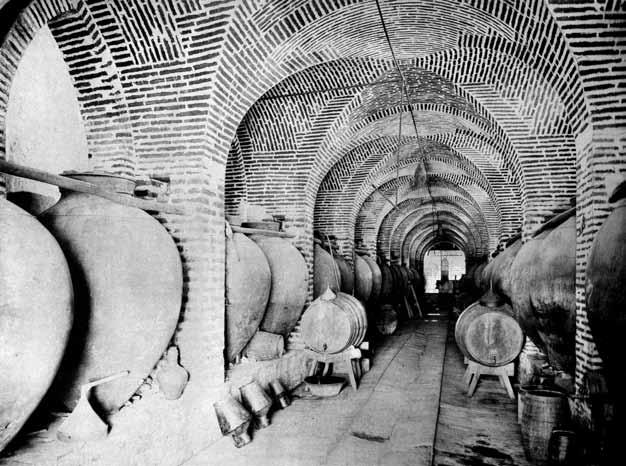

Vinho de ‘Talha’ DOC

In the 1980s the traditional Alentejano talha was almost redundant. The cooperatives that had transformed winemaking from the 1950s onwards either kept these huge clay amphorae as objects of ornament or left them to gather dust in the corner of an abandoned adega. Developed for making wine by the Romans, talhas are back in fashion and since

2010 have been protected by their own DOC, Vinho de Talha. This applies to all the subregions listed above. In the past, making wine in a talha was always something of a hit and miss affair, with traditions that differed from place to place. For the classic technique described by the agronomist António Augusto de Aguiar in 1876, the grapes were neither pressed nor trodden in lagar but crushed on the floor of the winery. The juice then ran off into a buried cistern or underground talha. But these cisterns (called a ladrão in Portuguese, meaning ‘thief’) also had a second purpose. Most of the talhas were above ground, albeit in semisubmerged adegas to keep them cool. If any of the talhas should burst during the fermentation (a real risk when the carbon dioxide pressure builds up inside), the ladrão would be there to catch the wine!

Talhas in the Alentejo, photographed for A Arte e a Natureza em Portugal, published in 1902

The traditional process for making wine in talha is as follows. The grapes arrive at the adega and are crushed and then, with or without stems, poured into the talhas. If a ladrão is being used, the must collected in it is poured back into the talhas using smaller vessels. At José de Sousa in Reguengos the talhas were lined with a locally made resin called pez that would impart some of its flavour to the wine. The adega would have a traditional slated table or mesa de ripanço: trays with

talhas 278–80, 298–9

Tavares & Rodrigues 179

Távora-Varosa region 227–8

Taylor’s 85, 88

Tejo region (formerly Ribatejo)

DOC 58, 253 geography 250–51 subregions 251–3 topography and climate 247–8, 249 vineyards 47 planting 58, 81, 252 winemaking 251

Torres Vedras subregion 157, 159 trade and markets exports and markets (2010–2020) 48 history

Staple Act (1663) 19

Methuen Treaty (1703) 15 expansion (late 1700s) 20–22

Forrester’s campaign (1800s) 23–5 exports (mid-1800s) 25–6, 31 range of wines 27 main markets

America 18–20, 29

Brazil 18, 27, 37, 40

England/United Kingdom 10–16

France 30–31, 40

Russia 27, 34, 35, 43

transport 41, 44, 163, 192, 225, 250

Trás-os-Montes region geography and climate 225–6

Valle Pradinhos 227 vineyards, DOC 190, 226–7

unfortified wines 171–2, 195–6, 205, 301–2

Vidigueira subregion 278, 284–5, 291

Villa Maior, Visconde de 50, 59, 62, 71, 72, 75 vineyards areas 45, 47

grape variety listing 58, 321–32 replanting after phylloxera 31–2 surveys of 50–52 traditional planting 49, 123 viticulture see viticulture see also grapes, red; grapes, white; and individual regions’ and subregions’ names

Vinho de ‘Talha’ DOC 278–9

Vinho Verde region climate 118, 123

DOC 121, 125 history 120–22

socio-economic changes 122–3 styles of wine 127–9 sub-regions and planting 125–9 vineyard methods 122–5, 128 wine by producers see producers vintages 115, 161–2

Viseu 230, 235

Viticultural Commission, Algarve 83 viticulture

arejão or arjoado (‘aired’ or ‘ventilated’) 123 cruzeta training 124–5 organic and biodynamic cultivation 74, 237, 239, 242, 290 taça (gobelet) pruning 66

vinha ramada (pergola-trained) 123, 126

Vizetelly, Henry, 27–8, 30, 31, 110, 170, 172

wine history

roots of wine 6–7

Port 13–16, 20–21, 30, 34, 35, 40, 69, 195

Madeira 18–20, 29 ‘Lisbon’ 12, 20, 156, 180–82

Pombal’s measures 16–18, 20, 141 mid-nineteenth century 25–9 disease and infestation (mid-1800s) 29–31 restocking and replanting 31–2 sparkling wines 313–14 first winery association (1895) 37–8 vineyard/grape surveys 50–51, 141–2 demarcation policies (early 1900s) 34–5, 54, 118 cooperatives 34, 37–9, 52, 156, 158, 229–30, 272

institutional changes under New State 37 registration of vineyards (early 1940s) 52 authorized’ and ‘recommended’ grapes 53 (1970s) 2–3, 120–21

EU reforms 3–5, 54 VITIS programme 44–5 single quinta, rise of 45–7 consultant winemakers 46 twenty-first century 47–8 production figures (1874) 38 (1908) 34 (2009–2019) 47 trade see trade and markets see also Portugal, history of; wines, brands and categories

Wine Society 28, 172

wine, unfortified 195–6, 205, 302

winemaking, talhas 278–80, 298–9

see also individual regions’ and subregions’ names

winery associations 37–8 wines by producer see producers wines of the plains 246, 247–9 wines, brands and categories

Abandonado 201

Alambre 261, 267

Altano 221

António 162–3

Atlantis Rosé 302

Barca Velha 196, 205–7, 209, 223

Batuta 211

Bucelas/’Bucellas’ 171–2

‘Bussaco’ 153–4

Casa das Gaeiras 166

Casal Garcia 132

Caves Velhas 174

Charme 211

Charneco 12–13

Chryseia 215

Corvos de Lisboa 169

Cova da Periquita 64, 259

‘Curiosity Red,’ 237

DoDa 211

Dourosa 219

Duas Quintas 216–17

Entre II Santos 147

Evel 218

Follies 132

Frei João Reserva 150–51

garrafeiras 115

Gazela 132

Gonçalves Faria label 147

Grande Escolha 115, 202

Grandjó 217–18

Grão Vasco 235

Guru 214

Incognito 67

João Pires 264, 266

Legado 208–9

‘Lisbon’ 156, 180–82

Manuel José Colares 179

Margem 209

Maria Teresa 204

Marquesa de Cadaval 255

Mateus Rosé 75, 226, 306–7, 309–11

Meia Encosta 234

Mirabilis 200, 212

Monte de Peceguina label 292

Monte Meão label 223

Monte Velho 287

Mouchão 294–5

Muralhas de Monção 136

Muros Antigos label 135

Ninfa 255

Nossa Calcário 148

Opaco 169

Osey 12–13

Padre Pedro 255

Pêra Manca 283–4

Periquita 266–7

Ponte das Canas 295

Porca de Murça 218

Porta dos Cavaleiros 229

Porta Velha 227

Prova Regia 173

Quinta da Chocapalha/CH labels 162

Quinta da Fonte do Ouro 234

Quinta da Fonte Souto 290

Quinta da Leda 206

Quinta da Manoella 214

Quinta da Romaneira 219

Quinta das Cerejeiras Reserva 168

Quinta de Gaivosa 201

Quinta de São Simão da Aguieira 234

Quinta de Simeans 133

Quinta do Azevedo 132

Quinta do Barão 182

Quinta do Carmo 282

Quinta do Cidrô 217

Quinta do Côtto 202

Quinta do Monte d’Oiro 165

Quinta do Mouro 295–6

Quinta do Noval Reserva 212

Quinta do Vale da Raposa 201

Quinta Nova 212

Redoma 200

rosé 305–8, 311–12

Faísca 308

Lancers 308–9

Mateus 75, 226, 306–7, 309–11

‘Series’ label 217

Sexy 289

Tannat 166

Teppo Peixe 137

Terrenus label 298