Ian Cheyne 1895–1955

Glen Cluanie, 1928

Colour woodcut on paper · 23.4 x 29.5 cm

Purchased 1949 · G ma 205

Cheyne was born in Broughty Ferry, near Dundee, and studied at The Glasgow School of Art. From the mid-1920s he specialised in colour woodcuts, teaching himself to work in a technique and style derived from Japanese prints, but adding his own, very lively Art Deco accent. Cheyne was one of a number of British artists in the early twentieth century who were discovering the techniques of colour printing first developed in China and later widely adopted in Japan during the Edo period (c.1603–1867). These artists, among them Cheyne, Frank Morley Fletcher (1866–1949), Allen W. Seaby (1867–1953) and Mabel Royds (1874–1941), commonly taught themselves, and others, how to make colour woodcut prints using books describing the intricacies of the Japanese process.

Cheyne cut eight blocks, now held in the Archive Collection at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, to make this print. There are four blocks of soft wood, each cut on both sides. Each of the colours in this print would have been printed separately, one on top of the other. The inking of each block would be done by hand and each colour superimposed on top of the other in precise registration. The complexity of this ancient process is neatly illustrated by the blocks themselves.

Fig.7 | Four of Cheyne’s eight wood blocks for Glen Cluanie Archive Collection, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

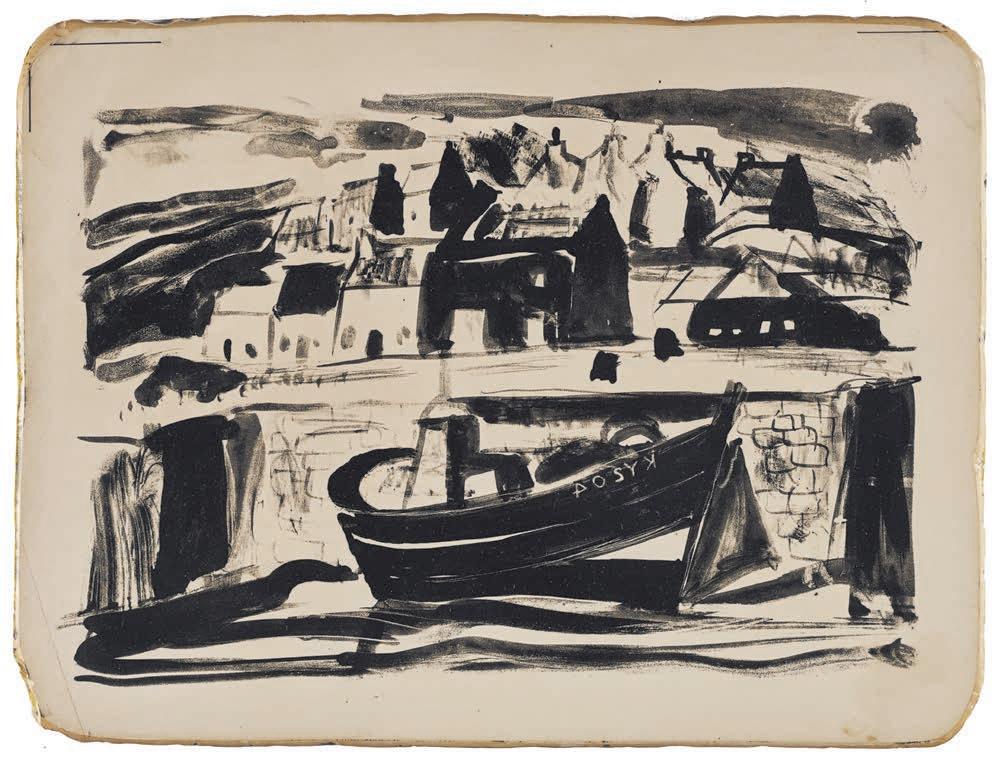

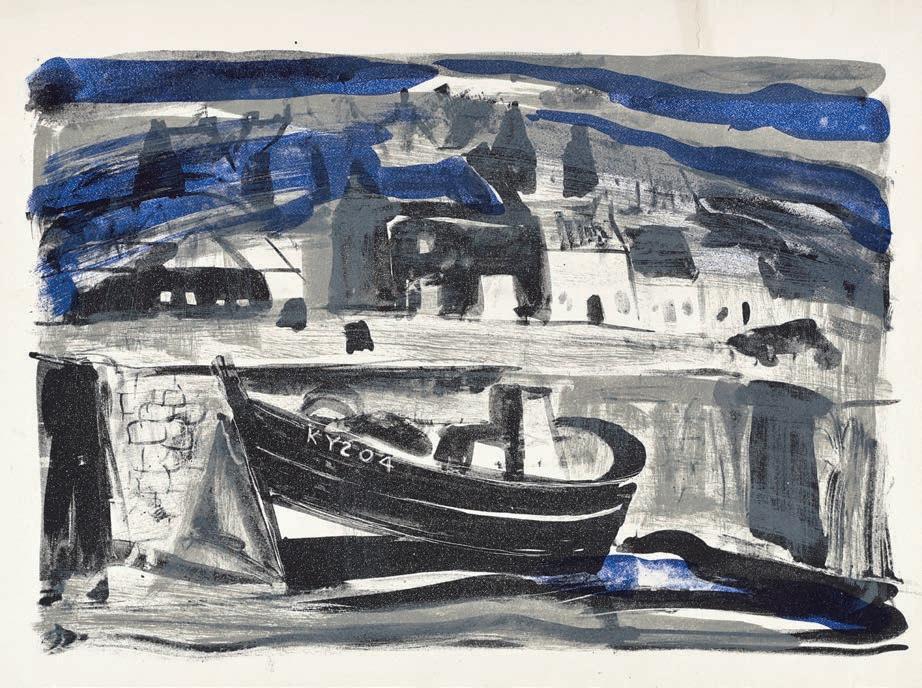

Fig.13 | Anne Redpath 1895–1965

Lithograph stone · 33 x 44 cm

Archive Collection, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

1895–1965

Trial pull from lithograph stone

Lithograph · 26 x 38 cm

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Fig.14 | Anne Redpath

Three Planographic Processes

The term planography refers to printmaking practices that involve taking the print from a flat surface, or plane. In relief printing the ink is deposited on a raised surface; in intaglio it is held in an incised or etched line. With planographic techniques, including lithography and monotype, the ink sits on the flat surface of the stone or plate.

Lithography

Lithography is a printmaking technique that relies upon the repulsion of oil and water to create an image held on a stone or metal surface, which can then be transferred onto paper. Due to advances in technology, and the invention of offset and photolithography in particular, lithographic techniques have dominated commercial printing from the late nineteenth century onwards. The advantages of lithography lie mainly in its painterly qualities – it remains the most faithful means of translating a drawn image into print.

In 1796 Alois Senefelder (1771–1834), an actor, composer and playwright, discovered through a process of experimentation with etching and printing in relief from stone

slabs, that the gum arabic and nitric acid solutions he was using had a transformative effect on the local limestone (from Solnhofen, Bavaria). What Senefelder had discovered was ‘adsorption’ – i.e. that the limestone is receptive to both grease and water and that, because the two repel each other, it was possible to ‘etch’ an image into the smooth surface of the stone. Marks made on the stone with a greasy substance (usually a soap-based litho chalk or ink, called Tusche) bond and sink into the surface of the stone. If the surface of the stone is then treated with gum arabic, the untouched areas are effectively sealed from any further contact with grease. The gum arabic penetrates into the surface and, because of its hygroscopic qualities (it is always ready to take up water), every time the stone is sponged with water, the oil based ink is kept away from the undrawn areas. Senefelder went on to develop the process, inventing transfer lithography, a special press (using a ‘scraper’ drawn across the stone), and inking techniques.

Traditional stone lithography, practised in the manner developed by Senefelder, is a somewhat laborious and complex method of printing. First, the stone has to be ground absolutely flat and smooth;

this is done by hand while the stone is wet, using a tool called a levigator with carborundum grit of several grades and sand as an abrasive. Alternatively, a second stone of similar size can be used for this first stage of grinding. Once the surface has been ground completely flat, the stone can be polished using pumice and snakestone to achieve a mirror-like surface (the surface finish will influence the quality of the finished print). Stones can be used multiple times: each time the image is ground away to provide a fresh surface to be worked on.

Some metals, commonly zinc and aluminium, can also be used for lithography. These have to be treated to give their surface a ‘grain’ which facilitates the subtle chemistry of the lithographic process.

Benjamin West 1738–1820

Angel of the Resurrection, 1801

Lithograph on paper · 32 x 23 cm

Purchased 1958 · p 2379

This lithograph, made only approximately five years after the invention of the technique, is widely considered to be the first artist’s lithograph ever made. West, then President of the Royal Academy, was one of a number of leading artists, including James Barry (1741–1806), Richard Cooper Junior (1740–1814), Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) and Thomas Stothard (1755–1834), who were approached to trial the process – first developed for duplicating plays and sheet music – as a means for producing multiple drawings. The results were published under the title Specimens of Polyautography, Consisting of Impressions Taken from Original Drawings Made on Stone, purposely for this work (1803–7). The subject of West’s print, a youthful angel heralding good news, is particularly fitting for a publication announcing a newly invented process.

This very early example has been made using a pen and greasy lithographic ink made from wax, soap and lampblack. From 1810 drawing with lithographic crayons became more usual. Although West has approached the design as if it were an engraving, using only line and areas of hatching, this ‘drawing on stone’ is striking in its directness.

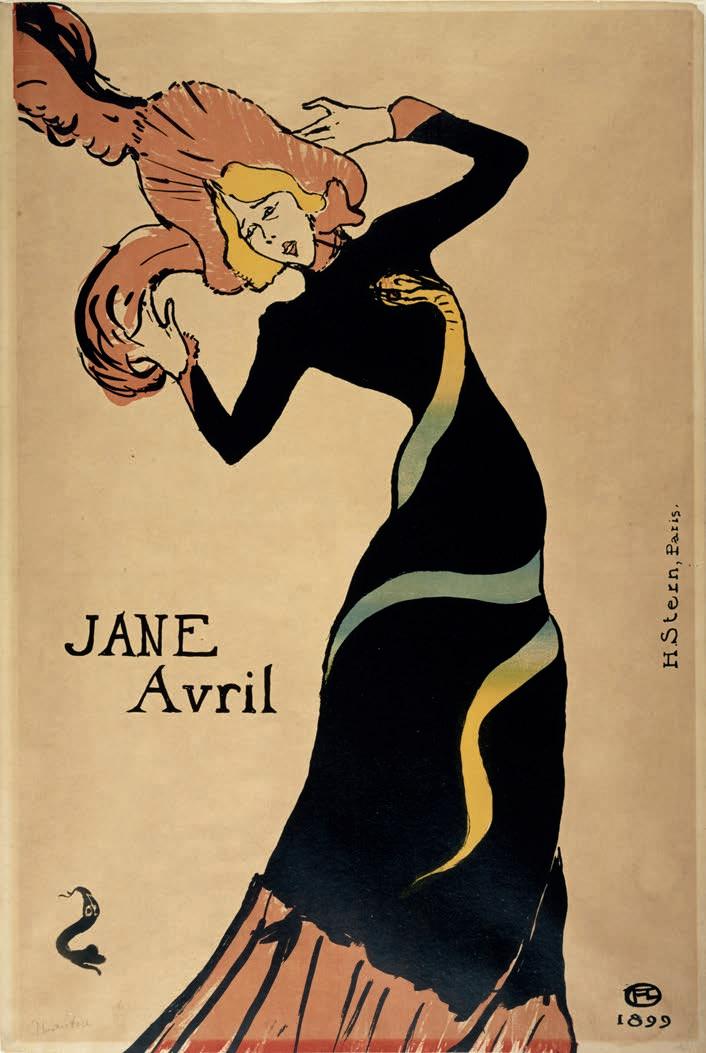

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec 1864–1901

Jane Avril, 1899

Lithograph in four colours on paper · 56 x 36 cm

Purchased 1963 · p 2557

For this print Lautrec first produced a carefully finished preparatory drawing of the design with colour notations. It is not known whether the design, which has been created using lithographic ink applied with a brush, was drawn onto the stone by Lautrec himself or, more likely in this case, by a lithographic artist (chromiste). The printed image has been made using four stones – a key stone printed in black and separate stones for the red, yellow and blue. The colour transition in the snake was achieved using a roller inked with varying degrees of blue and yellow ink. The printing was carried out by the Paris printer Henri Stern, who added the text, including his own name.

Lautrec was among the first and possibly greatest poster designers. Jane Avril is today considered to be one of the most powerful prints of his nine-year career in lithographic printmaking. At the time it was made, the poster was rejected by the dancer Jane Avril’s manager and as such its production was limited to a relatively small run. Surviving examples of the print are particularly rare.

Inkjet Printing

An inkjet print is a print made using a computer-driven printer which deposits tiny droplets of ink (cyan, magenta, yellow and black) in a pattern dictated by the digital information it is given by the computer onto the surface of paper fed into the machine. Like many techniques for producing a printed image, the bulk of the work is done beforehand – a photograph is taken, or an image is manipulated using computer software, and this is what provides the raw data for the printer. This differs from laser printing in that a laser printer deposits a pattern of toner on the paper surface, which is then fixed by exposure to heat; or dye sublimation which also uses heat. Dye sublimation employs a high number of tiny heated elements (hundreds per linear inch); the image is made by variations in temperature which affect the amounts of dye deposited on the sheet. Each of these processes relies on a discovery by James Clark Maxwell (1831–1879) in the nineteenth century. Maxwell, a physicist, discovered that every colour we see with the naked eye is actually made up of three colours, red, green and blue, and that these make up a second set of primary colours

–‘additive primaries’. This discovery has enabled colour printing through colour separations and is used by almost all digital printers. When mixed together, green and blue produce cyan, blue and red produce magenta, and red and green produce yellow. Digitally RGB (Red, Green and Blue) is converted to C m Y k (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Key / Black) for printing.

Alex Dordoy b.1985

Caster 3D , 2012

Inkjet print in three parts

Each part 135 x 90 cm

Purchased 2012 · G ma 5379

Dordoy was born in Newcastle and graduated from The Glasgow School of Art in 2007. He lives and works in London. This three-part digital print reflects Dordoy’s concerns with the boundaries between sculpture, painting and drawing as well as traditional and digital means of production. A heavily distorted figure appears in each part, laid over a twocolour background. The barely recognisable figure is the South African middle-distance runner Caster Semenya, who has intrigued Dordoy since the widely publicised controversy over the athlete’s gender during the 2009 World Athletics Championships. The fluidity of Dordoy’s approach is indicative of the level of experimentation encouraged by digital processes. Part of a generation accustomed to ever-present technology (he has said that working with Photoshop is as ‘intuitive as making a collage with paper and glue’), he is difficult to classify in the traditional sense, particularly as a printmaker. Dordoy’s techniques have included the manipulation of images in Photoshop, which are then meticulously translated into paint. It makes sense then that this three-part print is digital in all senses (digitally manipulated images, inkjet prints) and that it imitates painterly qualities and trompe l’oeil effects.