tec H niques of drawing

Copyright © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2025

Ursula Weekes has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. is B n : 978-1-910807-68-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Designed by Stephen Hebron

Printed and bound in XXXXXXXX

Frontispiece: Raphael Santi (1483–1520), Studies of the Heads and Hands of Two Apostles, c.1519–20, black chalk over pounced underdrawing touched with white chalk on laid paper, pricked for transfer, 49.9 × 36.4 cm. Presented by a Body of Subscribers, wa 1846.209

For further details of Ashmolean titles please visit: www.ashmolean.org/shop

Opposite: Fig.2 Paul Klee (1879–1940), Child with a Toy, 1908, pen and ink on paper on cardboard, 25.2 × 20.3 cm. Bequeathed by Mrs Margaret Wind in memory of Professor Edgar Wind, wa 2006.158

imaginal world of ideals and archetypes. As Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) said of the artist, ‘whatever exists in the universe through essence, presence or imagination, he has it first in the mind and then in the hands’.

The ancient and medieval worlds had countless master draughtsmen, but these artists and craftsmen tended to plan compositions on dispensable and temporary supports, such as scraps of parchment that would be thrown away, or tablets of boxwood and wax that could be reused by re-preparing the surface. As the manufacture of paper spread across Europe in the fourteenth century, the practice of drawing became more widespread and, for the first time, preparatory drawings were preserved as works of art in their own right.

In other parts of the world there was a long history of works of art on paper stretching back over 2,000 years. In China, the technique of making paper was known before the Common Era and was used regularly from the fourth century, and possibly earlier, in Buddhist scroll paintings, as well as for landscapes in ink, and watercolour. After the secret of paper spread from China to the Islamic world in the eighth century, paper was widely used in book production across the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa. Meanwhile, in India the earliest surviving manuscripts are Buddhist texts of the tenth century onwards, made on long, narrow palm leaves that severely limited the scale of drawing until paper became more prevalent under the Islamic Sultanates from the twelfth century onwards.

While the availability of paper played a decisive role in the development of drawing, a conceptual stimulus was also crucial for drawing to become valued as an independent pursuit. In the West, this shift first occurred in Florence in Italy as a result of the importance attached to the concept of disegno, namely the creative idea made visible in the preliminary sketch. Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) laid the foundations for this concept in his 1435 work De Pictura, by arguing that painting was a liberal art, not a craft, and therefore deserved to be held in high esteem as a pursuit ‘worthy of free minds and noble intellects’. Later in the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci attached a divine mystique to the notion of disegno, believing that the creativity of the artist re-enacted God’s creation of the world.

Among the drawings by Raphael (1483–1520) in the Ashmolean Museum is a double-sided sheet with studies for guards in a painting of the Resurrection (the project was never completed). The sheet serves as a paradigm for the stages of the creative process embodied in the Italian idea of disegno. Raphael’s pen races with ideas, which flow so quickly that he does not pause to use a new part of the page (fig.3). He seems to turn figures round on their axis or adjust their centre of gravity, searching for the poses he required. Raphael left this sheet and returned to it at a later stage in order to make a careful figure study in black chalk on the reverse side (fig.4). The pose of this large male nude seemingly evolved from a figure at the lower

Fig.10 Matthias Grünewald (1475/80–1528), An Elderly Woman with Clasped Hands, c.1512–15, charcoal on laid paper, 37.7 × 23.6 cm. Bequeathed by Francis Douce 1834, wa 1863.421

Opposite: detail of fig.25

Fabricated Chalks and Pastels

Fabricated chalks and pastels are made by mixing dry pigments with a binder to make a paste, which is then rolled into a stick and dried. The introduction of fabricated chalks and pastels allowed for a wider array of colours; by mixing two or more pigments, and by using white to vary chromatic strength, any number of colours could be created. Technically there is no difference between fabricated chalks or pastels, but the term ‘pastel’ became so closely associated with the soft effects produced in broad, colouristic drawings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that it is useful to retain a distinction between softer pastels and drier, friable (crumbly) fabricated chalks. Modern oil pastels have a different composition discussed below.

Leonardo da Vinci is apparently the first person to have made written reference to the medium of fabricated chalks/pastels, calling them ‘the manner of dry colouring.’ He recorded that he learnt the technique from a French artist called Jean Perréal (d.1530), who came to Milan with Louis XII (1462–1515) in 1499. Later in the same year, Leonardo made his famous portrait drawing of Isabella d’Este (1474–1539), now in the Louvre, Paris, in which he used yellow, brown, and pink pastels. During the sixteenth century pastels were primarily used to add light colour to portrait drawings, such Holbein’s famous portrait drawings of the court of Henry VIII (1491–1547) in the British Royal Collection. Italian artist Federico Barocci (c.1533–1612) often used pastels in his studies of heads and faces, such as Head of a Young Man, where pink and red chalk add warmth to the tone of the face (fig.22).

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the process for making pastel was described in two texts. The first, Syntaxes artis mirabilis, by Pierre Grégoire (c.1540–1597), published in Cologne in 1578, stated, ‘Painters fashion crayons in cylindrical form and roll them with a mixture of fish glue, gum arabic, fig juice, or what is to my mind better, whey.’ A year later, Gian Paolo Lomazzo (1538–1592) referred to a method of drawing ‘a pastello’ in his Trattato dell’arte della pittura (1584). Old recipes for making fabricated chalks, ranging from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, suggested a wide variety of binding media. In addition to those mentioned by Grégoire, there was plant gum (tragacanth), gypsum, milk, beer, and honey. The different binding strengths of these substances indicate how varied the texture of fabricated chalks and pastels could be. The recipes favoured by earlier artists suggest they inclined towards harder rather than softer fabricated chalks, perhaps because they copied the qualities of natural chalk more closely.

From the second half of the seventeenth artists began to use softer chalks to create ‘pastel paintings’, in which colours blended into one another by extensive use of a stump (a coil of paper or leather used for rubbing the

Opposite: detail of fig.30

Metalpoint

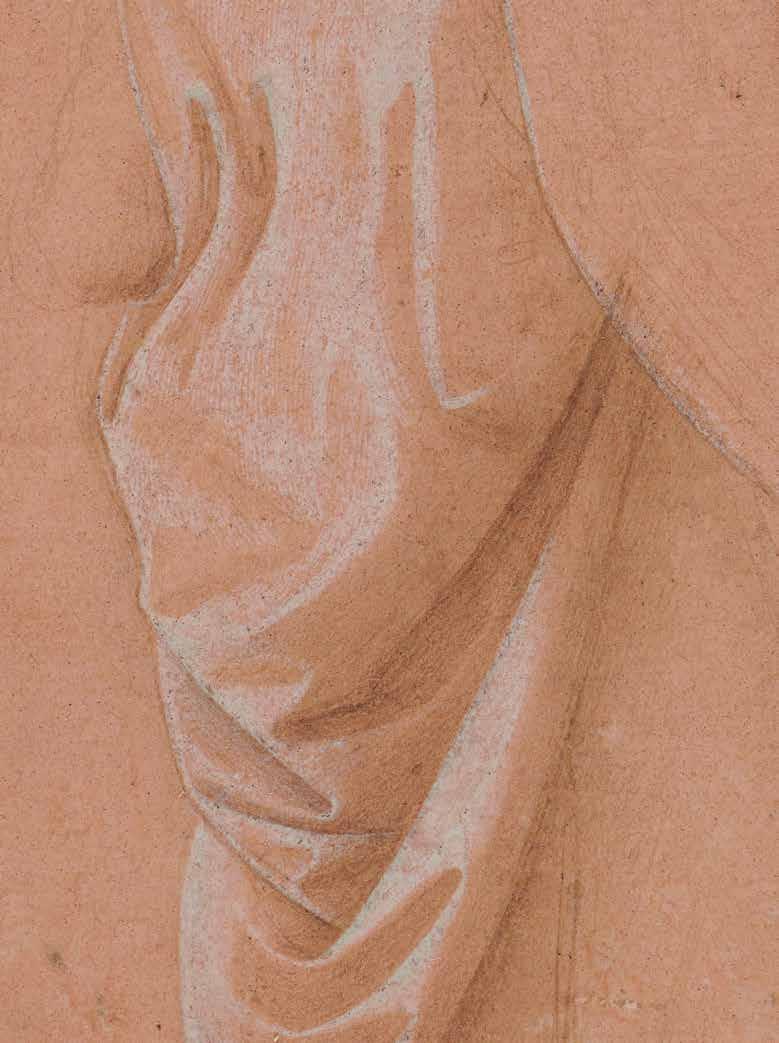

Metalpoint is one of the oldest drawing techniques in European art. Silver was the most common metal to be attached to the tip of a stylus and used for drawing, although lead, copper, and sometimes gold were also used. Metalpoint must be used on specially prepared paper, parchment, or boxwood in order to make a mark. Preparations for paper, also called ‘grounds’, were made either from lead white, ground bone, or ground eggshell. The powder was then mixed with glue water, normally made from an animal glue substance such as rabbit skin. Once the preparation had been brushed onto paper it provided the necessary polished surface for the stylus to leave a thin deposit of metal. Silver would quickly oxidise in the air and appear as a pale grey line; lead would give a stronger line, but its adhesion was weaker. Drawings in metalpoint give the impression of linear purity and preciseness because neither the width nor the tonal value of the line responds to changes in pressure. The application of greater force with the stylus merely scores the paper. In order to achieve greater tonal variety, Renaissance artists such as Filippo Lippi (1406–1469) liked to add coloured pigments to the prepared ground, such as the salmon pink in his Study of Drapery (fig.30). The colour would act as the mid-tone for the silverpoint drawing, with ink wash applied to shadows and white bodycolour to highlight accents. Drawings using this technique are known as three-tone silverpoint drawings and were characteristic of the fifteenth century.

Metalpoint was a familiar medium to medieval craftsmen, who used it for the preliminary stages of manuscript illumination to outline details of miniatures, borders, and historiated initials before painting. When drawing began to develop as an independent pursuit in the late fourteenth century, silverpoint was the first medium with which an artist would learn to draw. Cennino Cennini (c.1370–c.1440), in his Libro dell’ Arte (c.1390), considered silverpoint to be more valuable than any other drawing technique for training a young artist because of the control and discipline that it demanded of the draughtsman. During the fifteenth century, Italian artists such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Pietro Perugino (1446–1523), and Filippo Lippi (1406–69) excelled in the use of silverpoint, as did Netherlandish and German artists of the same period. One of the Ashmolean’s finest silverpoint drawings, Head of an Old Man (c.1435–40), attributed to a follower of Rogier van der Weyden (c.1399–1464), relates closely to the head of Joseph in the Nativity scene of the Miraflores Altarpiece (1442–5) in Berlin (fig.31). The exquisite tiny study captures each line of the face and each hair of the beard with hyper-realistic precision.

Chinese painting fell into two main techniques: the first known as ‘meticulous’ (gongbi) with detailed brushwork often in a highly coloured palette done by court artists and independent workshops (discussed under opaque watercolour), while the second is known as ‘wash and ink’ (shuıˇ mò), practised by scholar gentlemen, known as literati painters. The golden age of wash and ink was considered to have flowered during the Five Dynasties to Northern Song period (907–1207 ce ), but in the centuries that followed many literati Chinese artists perpetuated an unbroken tradition with their forebears, honouring the legacy of personal artistic expression.

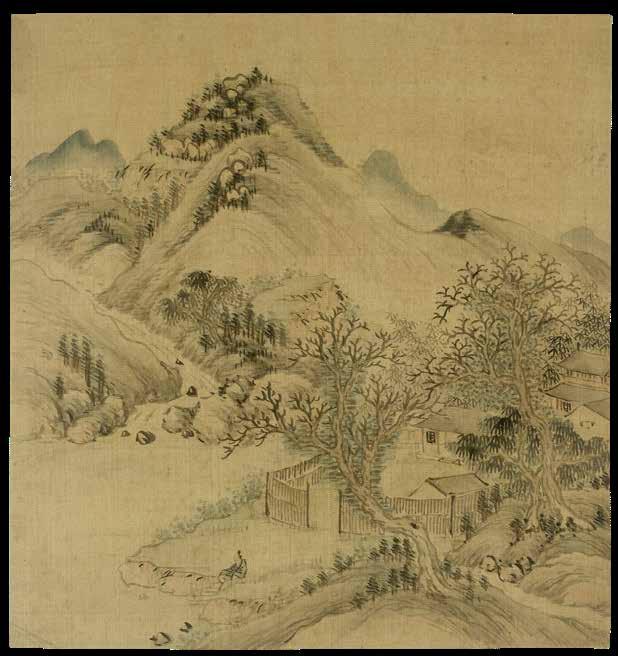

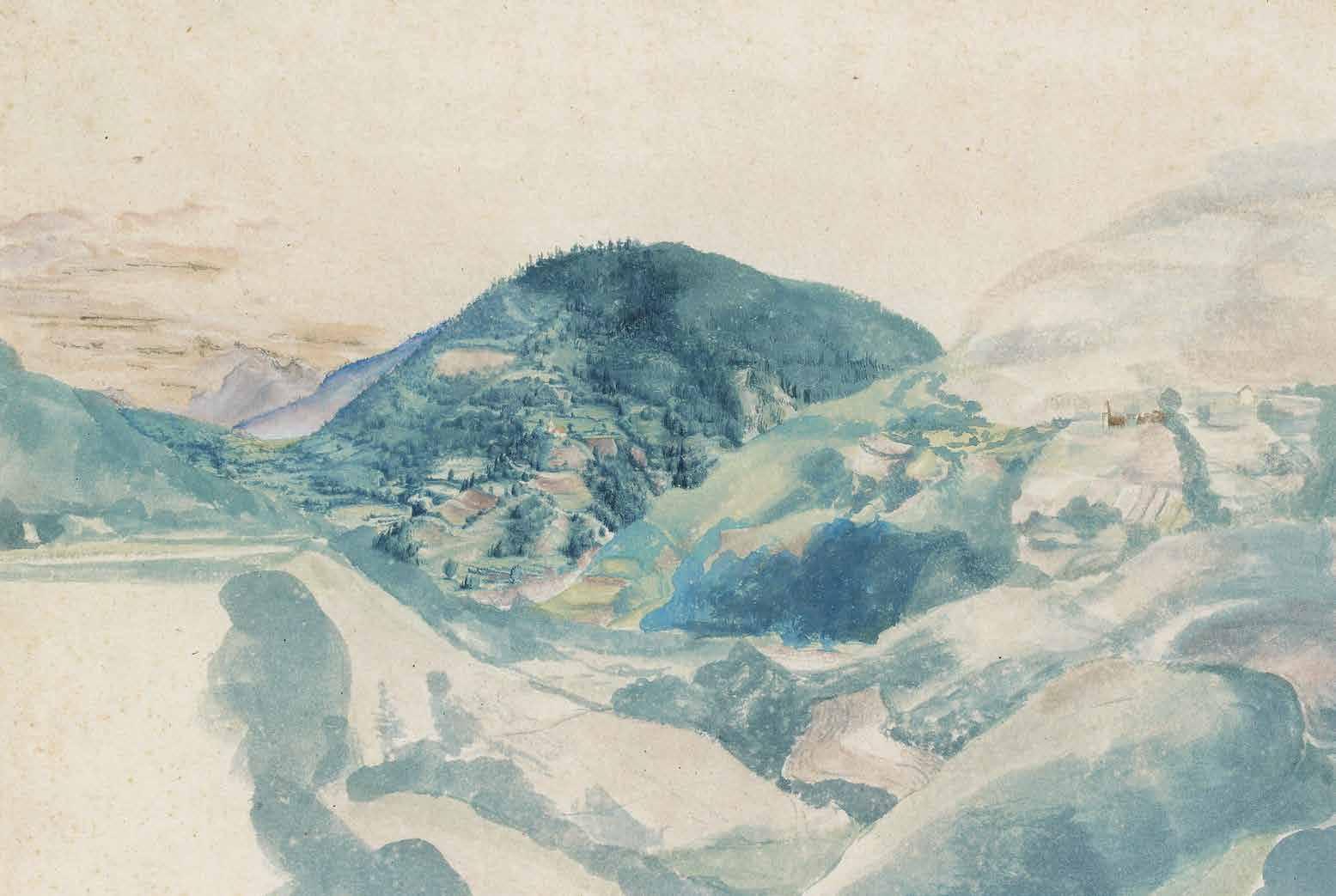

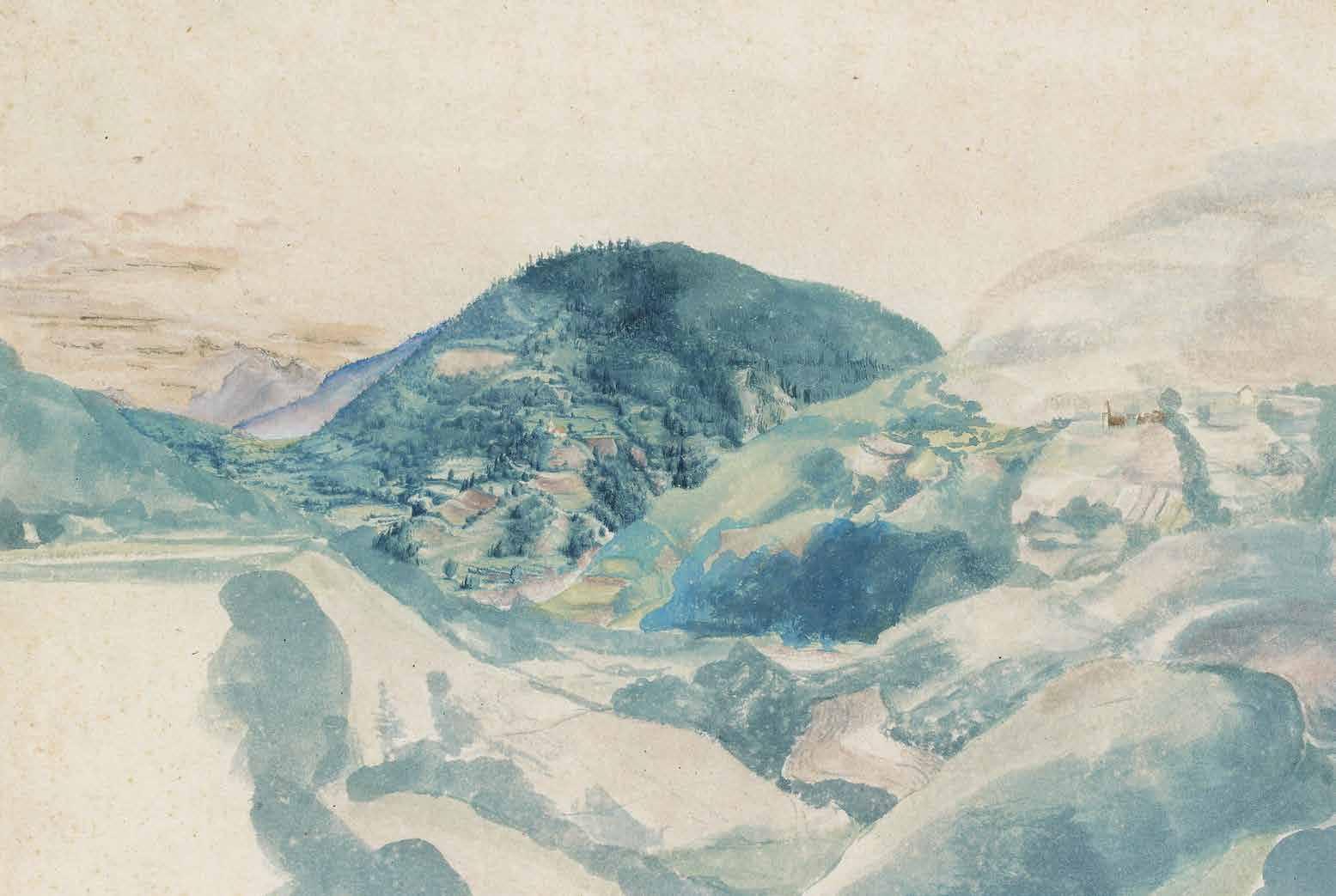

Chinese brush drawings are famous for their atmospheric landscapes and nature studies. Qian Gu’s (1508–78) Landscape with Houses and a Figure Sitting by the Riverside, 1574, comes from an album of exquisite landscapes in the Ashmolean (fig.42). Born in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, Qian Gu was a pupil of the famous Ming master Wen Zhengming (1470–1559). The trees in the lower right foreground lean towards the mountain that rises majestically in the distance, while the solitary figure in the foreground sits quietly on the edge of the composition.

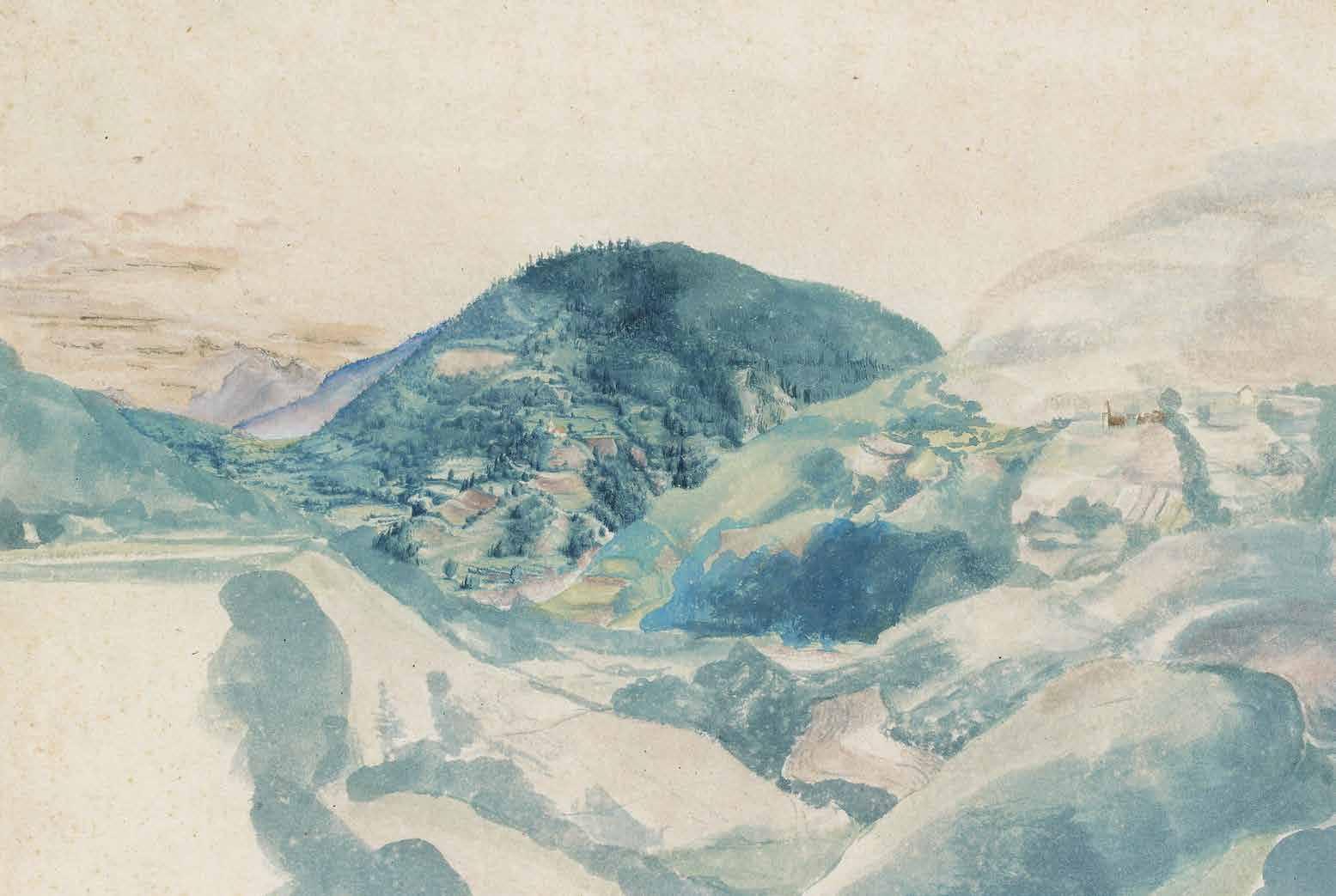

According to the sixth-century Chinese art historian and artist Xie He (active 500–535) whose treatise Gu Huapin Lu (Ranking of Painters) lays out six aesthetic principles of Chinese painting, the first priority of the artist was to convey inner liveliness through ‘spiritual resonance and lifelike motion’ (qiyun shengdong). Another key principle was transmission of the ancients by copying (chuanyi), showing the importance of tradition in Chinese ink and wash drawings. Wu Hufan (1894–1968) embraces these principles in his brush and ink drawing, River and Mountain Landscape (1916), with its accompanying inscription acknowledging the artistic inspiration of his work:

Guo Xi [c.1023–c.1090] painted rocks as clouds, as Wang Yuanqi [1642–1715]

once said. I have not seen Guo’s painting; I only saw Wang’s copy. Here I tentatively imitate it within the limits of Wang’s achievement. So comes the saying of ‘painting rocks as clouds’. I paint this for Mr Yunshi.

Wu Hufan thus pays homage, through his inscription and the drawing itself, to the inspiration of a thousand years of artistic tradition in China (fig.43)

While Wu Hufan focuses on the aesthetic heritage of the brush, a more practical emphasis on making suitable brushes comes to the fore in a late sixteenth-century Persian text, Qanun al’ Suvar (Rules of Painting), c.1597, written by painter and poet Sadiqi Beg (1533–1610):

When you develop an interest in naqqashi [painting] then first of all you should learn the art of making brushes … so that you are not dependent on anyone. The brush for naqqashi should be made from the soft hairs of a squirrel’s tale.

Some brushes comprised just two squirrel hairs so that artists could achieve a microscopic level of detail. It should be noted that a brush cannot have only

Fig.42 Qian Gu (1508–1578), Landscape with Houses and a Figure Sitting by the Riverside, 1574, brush and carbon ink with light colour on silk, 25.5 × 24.5 cm. Presented in honour of the 80th birthday of Angelita Trinidad Reyes, ea 2012.185.d

Fig.44 Abu’l Hasan (1589–c.1630), St John the Evangelist, after Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), 1600–1, brush and ink with touches of gold and white on burnished paper, 10.0 × 4.6 cm. Gift of Gerald Reitlinger, ea 1978.2597

Fig.45 unknown Kota artist, Head of an Elephant, 1700–1710, brush and carbon ink on paper, 23.8 × 23.9 cm. Presented by Howard Hodgkin, ea 2016.23

(Florence, 1681); Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 2 vols (New York, 1904); Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte [1390] (Vincenza, 1971); Petrus Gregorius, Syntaxeon artis mirabilis (Cologne, 1583); Xie He, Gu Huapin Lu [c.550] in Susan Bush and Hsio-yen Shi (eds), Early Chinese Texts on Painting (Hong Kong, 2012); Carl Friedrich August Hochheimer, Chemische Farben-Lehre (Leipzig, 1797); Samuel van Hoogstraeten, Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst (Rotterdam, 1678); Charles-Antoine Jombert, Methode pour apprendre le dessin (Paris, 1755); Constant Viguier and F. P. Langlois de Longueville, Manuel de Miniature et de Gouache suivi Manuel du Lavis à la Sepia et de l’Aquarelle (Paris, 1830); Leonardo da Vinci, The Codex Atlanticus of Leonardo da Vinci, A Catalogue of its Newly Restored Sheets, C. Pedretti (ed.) (New York, 1979); Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Trattato dell’arte della pittura, scoltura et architettura [1584], ed. R. Ciardi (Florence, 1973); A. F. Lomet, ‘Mémoire sur la fabrication des crayons de pâte de sanguine employés pour le dessin’, Annales de Chimie, vol. 30 (Paris, 1799); Theophilus, De Diversis Artibus [1110–40], C. R. Dodwell (ed. and trans) (1961); Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite De’ Più Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori e Architettori [1550, 2nd ed. 1568], G. Bull (trans), Lives of the Artists (London, 1987); Giovanni Battista Volpato, Del preparare tele, colori od altro spettante alla pittura, ed. Giambatista Baseggio (Bassano, 1847).