HistOry

progue 1877–1923

salviati-barovier

In 1877 Antonio Salviati (1816–1890) withdrew from the Venice and Murano Glass and Mosaic Company Ltd and founded two new companies: Salviati & C. – Società in nome collettivo, together with Siegmar Elster (an investor from Berlin) for the production and resale of mosaics,1 and Dr. A. Salviati & C. for the production and resale of blown glass.2 Several former workers of the Venice and Murano Glass and Mosaic Company Ltd followed Salviati. Among them was Giovanni Camozzo, who remained a technician, while members of the Barovier family, among which included Giovanni and his nephews Giuseppe, Benvenuto, and Benedetto, became Salviati’s master blowers.

In 1882 Maurizio “Moisé” Camerino (1859–1931) entered the service of Antonio Salviati. He was the general manager when in 18843 the latter decided to concentrate on retail only. In exchange for the exclusivity of their production (including novelties), Salviati assigned his fully equipped glass factory to the Barovier family. Under its various successive denominations this glass plant played a prominent role in the events which led to the foundation, growth, and flourishing of Studio ars et labor industrie riunite, known as S.A.L.I.R.

After the death of Antonio Salviati in 1890, his heirs —Silvio, Giulio, and Amalia—together with Ernesto Salviati, Ugo Gelsomini, and Angelo Raffaele Cuzzi founded Dr. Antonio Salviati & C. – Società in accomandita semplice, for the retail and production of Venetian specialties but excluding large mosaics and blown glass. 4 The headquarters was located on the third

floor of Palazzo Bernardo in Venice. Their wide range of offerings also included glass objects (contractually blown exclusively for them by the Barovier glassworks on Murano) which were adorned with engraved gold foil and enamel decorations by the Venetian firm of Giovanni Pitteri and Enrico Luchesi.

giovanni pitteri

In 1893 Giovanni Pitteri (1868–1927) and Enrico Luchesi founded a company decorating glass and porcelain with gold and enamel ornaments a fuoco at San Gregorio 234–238 in the Dorsoduro area of Venice. The company was successful and received awards at the Esposizione di vetri artistici ed oggetti affini di Murano e di Venezia 5 This important event had been organized in 1895 by Isidoro Barbon, Mayor of Murano, at the occasion of the first Biennale d’arte di Venezia. When Luchesi withdrew from the company, Pitteri continued alone. In March 1909 he moved the workshop to Via Tolentini/Fondamenta Rizzi 298–302 in the Santa Croce district, where he was joined by his son Primiero “Primo” (1890–1974).6 Through Dr. A. Salviati & C. they continued to order glass objects from the Barovier glassworks (1–3), while the undecorated porcelain was provided by the factory of Hermann Ohme in Nieder-Salzbrunn (Silesia). The outbreak of World War I obstructed the workshop’s daily routine and production was ceased. After the war, a new start-up necessitated fresh capital, which was provided by a recently founded investors’ group headed by Luigi Bisigato (1881–1964).

1 + 2 Pitteri and Luchesi photograph, representing porcelain tableware with enameled “lace” decoration featuring labels by Dr. A. Salviati & C. and a Pitteri order form for blanks. Photo: Tomaso Filippi. Archives S.A.L.I.R., Murano.

3 Giovanni Pitteri, a smalto bowl “Putti e festoni,” 19 × 33.5 cm, c. 1910. Double-sided enamel decoration inside and out. Enameled signature “P. D.” Marc Heiremans Collection, Antwerp.

This approach was quite apparent in an important renewed collaboration between S.A.L.I.R. and Cristalleria Nason & Moretti. 47 Both companies had cooperated in previous years, during which S.A.L.I.R. had decorated part of its production with enamel (21+ 22). Above all known for well-designed tableware, Cristalleria Nason & Moretti predominantly used mold-blowing for their output. In a bid to reduce costs, S.A.L.I.R. asked Franz Pelzel to design some simple shapes suitable for mold-blowing by Cristalleria Nason & Moretti which were easier to produce and thus at a lower cost. This production possibly inspired the latter in turn to initiate an artistic output of its own. Between 1934 and 194048 this semiindustrial glass plant offered an exclusive catalogue of mold-blown objects artistically engraved by S.A.L.I.R. A number of the motifs were derived from former Balsamo Stella designs, while others were possibly provided by the by the Cristalleria Nason & Moretti.

As for many other glass companies on Murano, the mid to late 1930s was a prosperous period, one in which the largest part of S.A.L.I.R.’s production, mostly tableware and mirrors, was destined for export. In March 1936 the founding contract was due to be prolonged, and Guglielmo Barbini took the opportunity to withdraw in order to work independently.49 This left Decio Toso and Giuseppe D’Alpaos as sole partners. As general manager, Decio Toso became mainly responsible for administration, while Giuseppe D’Alpaos also actively participated in the day-to-day production. In this capacity he became the inventor and prime executor of the traforato technique, the lace-like perforation of blown vessels through sandblasting.

Additionally in 1936 the investment company S.A.I.A.R. absorbed both Vetreria artistica Barovier S.a.s. and Vetreria Barovier S.n.c., which—merged with the Ferro Toso & C.—led to the foundation of Ferro Toso Barovier – Industrie artistiche reunite S.a.50 Henceforth, this new glassworks provided S.A.L.I.R. with the necessary blanks. During this period the factory was frequently solicited by E.N.A.P.I.’s Ufficio artistico, for which it executed designs by Ernesto Puppo, Umberto Zimelli (1898–1972), Erberto Carboni (1899–1984), and Eugenio Fegarotti (1903–1973); most of these were sent to the VI Triennale di Milano that same year.

Notwithstanding its comfortable position, in 1937 S.A.L.I.R. declared that it employed only six workers, of which two were male engravers and four were female decorators.51 But the growing, predominant output of tableware and mirrors necessitated additional grinders. As such, Wladimiro Scatolin (b.1922) entered its service in 1937 and Giorgio Zecchin (1923–1944, son of Vittorio) in 1938. While both started as molatori, they successfully trained as skilled incisori. This aberrant training might be seen as anticipating that Franz Pelzel—a German citizen—

Each title on the third list (the chalices) refers to a specific plate in a binder once used by Giovanni Pitteri. This binder consists of fifty-four consecutively numbered plates, each with a hand-colored drawing of a chalice. These calici were at the time offered as individual works of art, even though some models

could, on request, be developed into a complete set of tableware. The fact that some plates are doubled indicates the former existence of a second copy. Unfortunately, only few objects on the written list bare reference to a specific plate. One can assume that at least some of the objects on the list feature among the colored plates, but their generic descriptions do not allow further reliable connections.

90 Vittorio Zecchin, “Foglie,” “Smalto” models 722, 9 × 14 cm, and 723, 10 × 14 cm, 1940. Holz Collection, Berlin. Drawing archives S.A.L.I.R., Murano.

75

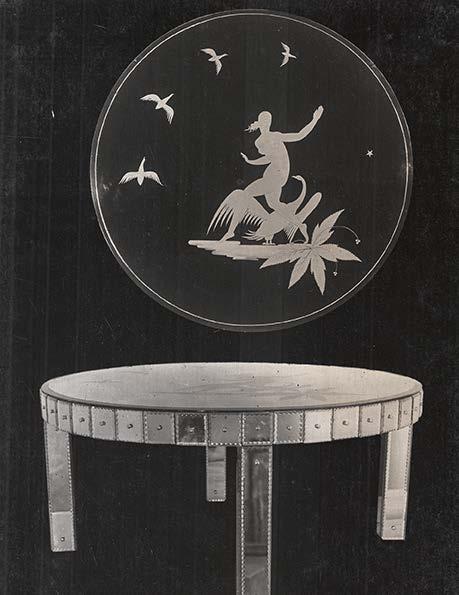

76 Guido Balsamo Stella, table mirror “Danzatrice” model 353, Venice, 1931–32. Drawing archives S.A.L.I.R., Murano. Photo by Zaniol, Murano, photographic archives S.A.L.I.R., Murano.

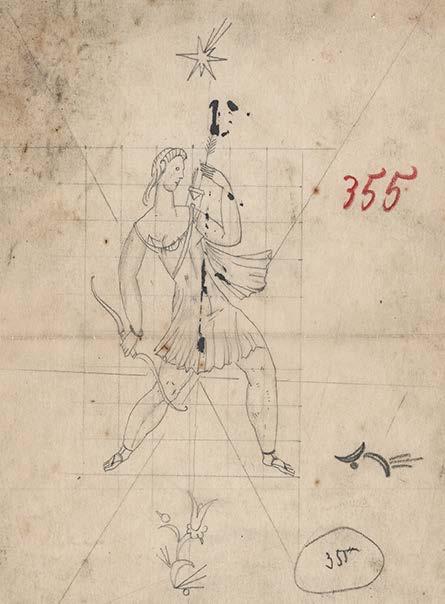

77 Guido Balsamo Stella, “Diana cacciatrice” model 355, Venice 1929–30. Free-blown blank S.A.I.A.R. – Ferro Toso, catalogue model 347. Drawing private archive Venice. Photo by Giacomelli, Venice, photographic archives S.A.L.I.R., Murano.

78 Guido Balsamo Stella, “Donna sulle scale” model 356A, 30 × 26 cm, Venice, 1929–30. Unidentified free-blown blank

179

180

Executed by mediation of the Fucina degli Angeli in December 1961 in an edition of three, this being 3/3.

Signed certificate from Egidio Costantini, dated December 9, 1961.

17

20 cm (adaption of S.A.L.I.R. model 344), Drawing archives S.A.L.I.R. Murano.