by LUIGI MASCHERONI

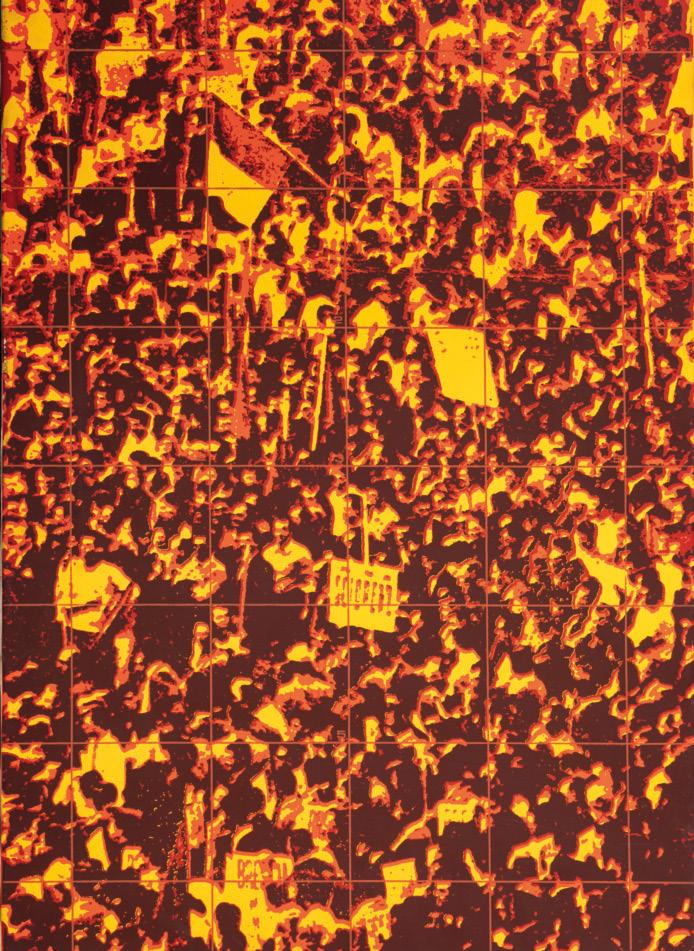

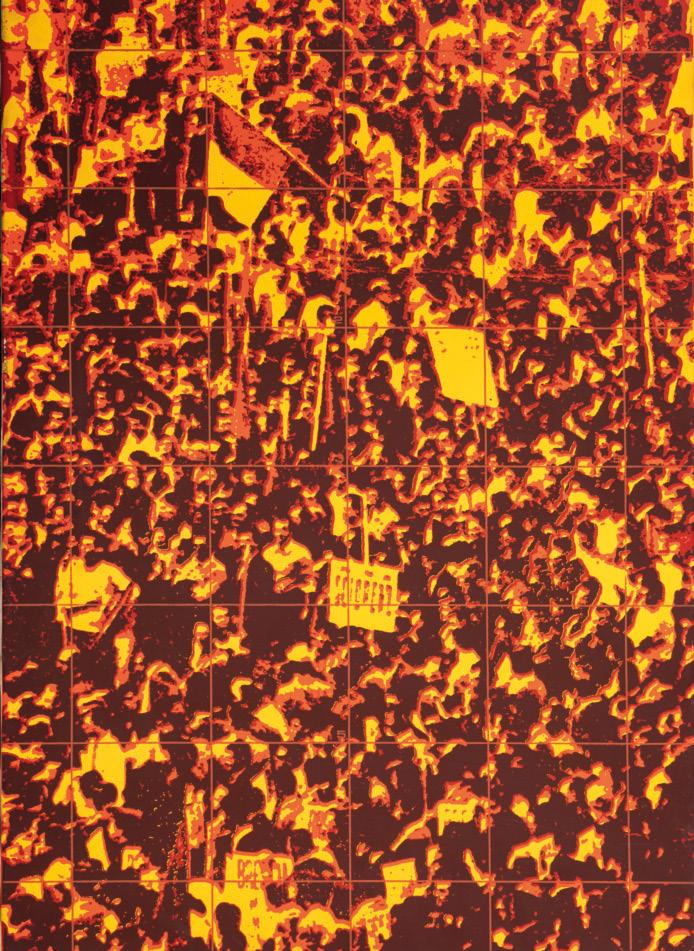

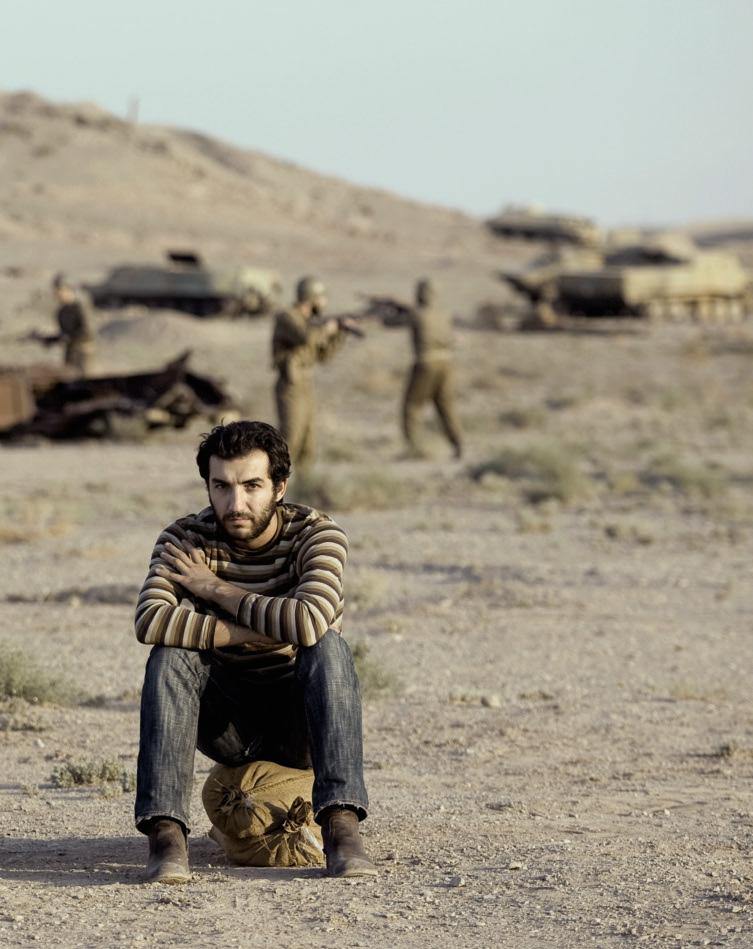

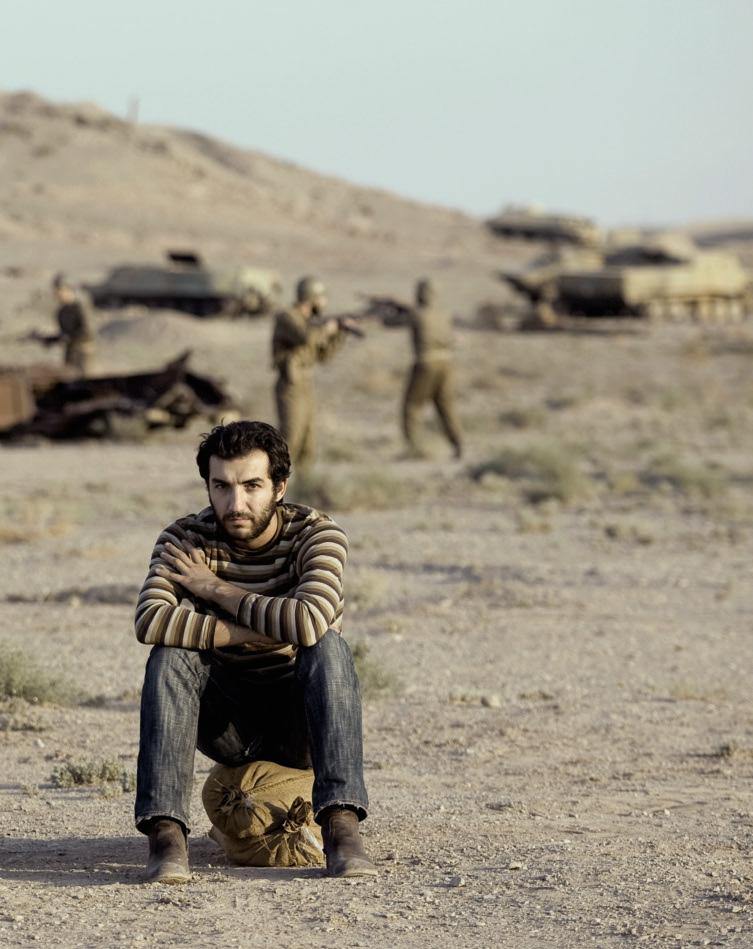

This is a time of warning signs: we feel that something is about to happen, but we are not sure what. A time when we sense an impending drama, but it is as though we are paralysed. A time when the sky darkens, we perceive that it is about to rain, but we continue to wait uncertainly, in a land full of possible catastrophes. Some have called it anteguerra: antebellum, pre-war. Something akin to a long moment of bated breath, when we sense danger but cannot bring it into focus. We pick up clues, but we are unable to read them. We see the outlines of a shadow, but we do not recognise the substance that produces it. Anteguerra is future battlefields. These don’t have to be military, but may be geopolitical, environmental, demographic, social or economic. Anteguerra is the twittering before the storm, as Filipino artist Markus Salvatus demonstrates. It is an “inminencia de precipicio”, as the Spanish writer Javier Cercas suggests. It is a time of suspension, as philosophers Silvano Tagliagambe and Felix Azhimov put it in their reflections. It is the gathering clouds looming over the present that we are warned about by Denis Brotto and Russian director Alexander Sokurov. It is the event horizon, gazed at from the edge of a black hole, as recounted by the scientist Cinzia Zuffada from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California—one of NASA’s temples, where ideas thrive and space exploration technologies are born. It is the destructive potential that is within each of us and that we must learn to manage, as explained by the Spanish psychoanalyst Josep Oriol Esteve. Or it is the inurement and daily routine of surviving in a war zone, as attested by the Iranian artist and photographer Gohar Dashti. Above all, it is something that arrives from afar, is not immediately understood and ends in tragedy, as the artist Wael Shawky makes us see and feel with Drama 1882. It is the staging of a historical event from almost a century and a half ago,

WORDS BY WAEL SHAWKY Artist

CHRISTINE MACEL

Conseillère artistique et scientifique auprès du Président Conservatrice générale du patrimoine

Tusk a cependant annoncé que l’Europe entrait dans une ère d’avant-guerre en Europe il y a déjà un an. Les nouvelles générations doivent «s’habituer mentalement à l’arrivée d’une nouvelle ère [...] L’ère d’avant-guerre. [...] Cela devient de plus en plus évident chaque jour». Donald Tusk évoque même « le moment le plus critique depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale». J’étais en ce mois de février à Varsovie pour l’inauguration du nouveau musée d’art moderne et contemporain, fruit de la persévérance de sa directrice, Joanna Mytkowska, qui, après avoir œuvré avec moi sur l’exposition Les Promesses du passé au Centre Pompidou en 2009, qui regardait justement à l’Est de l‘Europe, a passé quinze années à bâtir ce musée tout blanc face au Palais de la Culture et de la Science, et constitué une collection d’artistes polonais et internationaux d’où ressort en partie une forte implication politique. La menace de la guerre était palpable dans la capitale de l’ancien allié russe. A l’entrée se trouvait une œuvre d’Alina Szapocznikow, Friendship (Monument to Polish-Soviet Friendship) de 1954, un gigantesque bronze autrefois placé au Palais de la Culture,

I am an independent artist and, especially after the revolution in 2010, I decided that I was no longer going to show my work in Egypt. When the invitation came, at the beginning I refused, then I started to negotiate this and discussed it with the people I trust, and everyone told me that I must participate. Sometimes it’s good to let your voice be heard in a country, even if you are against its politics, because it’s not often that you get the chance.

The very concept of the Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, helped me delve deeper into this topic in telling the story of how the British occupied Egypt. The reason for the occupation was, as you see from the film, a fight that happened in the streets of Alexandria where a Maltese man killed an Egyptian, and this murder gave rise to a big fight that led to the killing of almost 300 people. This is what we think, because the story is not really 100% clear. And even this man, this Maltese guy, the killer, was already protected by the British. To this day, we don’t even know his name. Even in our film he’s called “Anonymous”. What we know is there was a fight in Alexandria, and we know that the British said we have to protect our subjects in Egypt and among these subjects were the Maltese. So that was the excuse for the British to attack.

The first attack was on Alexandria; they killed something like 2,500 people. They completely demolished all the buildings in downtown Alexandria. If you see some of the photos, it will remind you of Gaza. It was pretty similar. Then, after one month, they occupied the entire Egypt, and they stayed there 73 years. The idea is that this part of history, for many scholars, seems to be staged. It’s something that feels made up in order to give the excuse to the British to come to Egypt. So that’s why I thought I needed to staged this story as a play and then film the stage play. So it was really like staging the historical past. This is the thing that always happens with history: you’re never 100% sure if the events occurred exactly as they were written down. But this is part of why I like to work with history so much: because of this gap of the imagination, that we still can imagine what happened. So that was the thing that led into this idea of making a musical play to be filmed. I had very little time because I was called in only eight months before the Biennale. And I had maybe two months of negotiations with them to get all the permits and my conditions approved. There would be no censorship in the work. They wouldn’t have the right to see it beforehand. And they couldn’t even come into the pavilion before I was done with the installation. They gave us the key and they agreed on everything. To be honest, they were very respectful. They were so proud of the result, after all the success and everything. So we came back to Egypt and made a presentation at the Opera House and even at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. It was an incredible chance

représentant deux hommes aux corps interpénétrés, qui rappelaient un temps où la Russie et la Pologne avançaient comme frères siamois, relique d’un temps bien révolu. Face à elle, se trouvait Gazelka (Petite gazelle, 2015) un drapeau de métal réalisé à partir d’un fragment d’un véhicule russe, récupéré par les Ukrainiens en 2014, perclus de tirs de balles. Réalisé par l’artiste Nikita Kadan, une des voix les plus audibles et fortes aujourd’hui de la résistance des artistes en Ukraine, cette œuvre montrait que la guerre était déjà là bien avant 2022.

Le climat d’avant-guerre qui règne en Europe mais qui n’augure pas pour autant de son issue – un climat pour lequel on recherche des points de comparaison avec celles de la dernière guerre mondiale comme si l’histoire se répétait – a par ailleurs peu de répercussions aujourd’hui sur le plan artistique, comme si ceux qui ne sont pas touchés directement se trouvaient justement en suspens. Pourtant le drapeau est déjà percé Et la prochaine Biennale Arte ne pourra cette fois plus que jamais en détacher le regard.

for me because part of my mission as an artist is education. I also have a non-profit school in Alexandria called MASS. So it was also great for me this time to work with young stage performers, as I’ve never worked in this field in Egypt before. Many, many young people some of whom are not professional actors; many of them just like theatre. And the idea that to work with all this amount of people, more than 130, 140 performers plus carpenters, plus the film crew, it was really huge, huge stuff. And everybody really put their heart in this. It was an incredible experience. Especially this time that I decided to compose the entire 45 minutes myself. First I had to write it, then I started to compose it. And to do that I had to sing it from start to finish, because it was the only way for me to explain to the musicians how it should be played and sung. Because it’s different scales. If you look at Arabic music, for instance, it’s not only in Nahuant, you go from Saba to Nahuant, back to Saba, and so on. And I couldn’t really explain it. I had to sing it myself and play it on the keyboard and then we had the arranger make it with the other instruments and more singers and so on. Another big challenge was to work with the choreography. Because I had this idea of how people needed to be moving not only in slow motion, but in layers. So sometimes you feel that the whole group is moving as one single body. That’s why I call it drama, because actors are sort of hypnotised and they are moving in groups sometimes they are moving in a very slow motion, they are singing and you see that they are sometimes two groups just moving slowly leaning towards each other and this is basically coming from reading the historical letters from the leaders one to another. And you see that sometimes one person is more dominant than the other. And this idea of movement in the choreography comes from who is going to be dominant at each turn. This type of political debate is about dominance. Each scene looks like a moving painting. I’m originally a painter. So for me, the idea is to try to make each scene a painting, but at the same time, musical and moving. And also you see this in the scenography itself. The scenography matches the main characters and the extras, and the music, and the colours of the costumes: everything matches. The same way we try to work with painting. What we try to do with this type of slow movement is to stretch time, to make you feel that time is very, very, very stretched out and at the same time, condensed. You take in so many political events in just 45 minutes, but with this slow movement you still feel that time is dilated. I don’t know how to explain it better, this is the type of combination that I always like to have it in my work, which is very grotesque, very violent, but at the same time a bit comical. It has its own humour. It’s visually very beautiful, but at the same time there is a lot of violence, the work has its own violence. Hence this idea of using time and slow motion in this work.

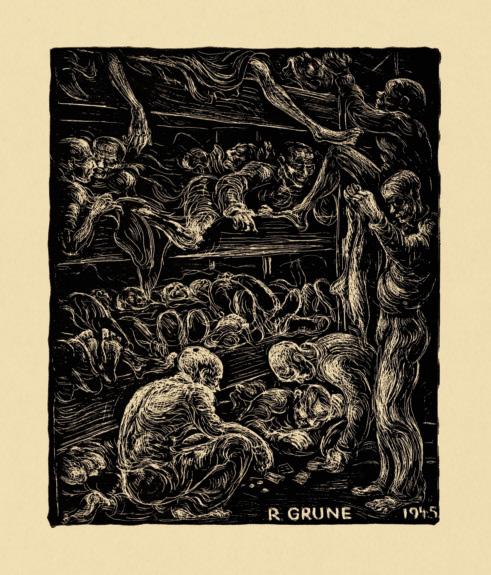

Architecture Historian

Civilisation is fragile and our perspectives can change quickly. But some “emergency housing” used in the past teaches us how to respond to wars, catastrophes and pandemics when buildings and infrastructure are destroyed. And the prefabricated barrack, like those used in concentration camps, remains the most political architecture ever conceived. Where “political” means the art of living together

Gaston Bachelard, ne La poetica dello spazio (La Poétique de l’espace, 1957), spiegava come gli ambienti siano in grado di plasmare la personalità, generare emozioni e influenzare la percezione. I luoghi che ospitano gli eventi della vita non sono semplici quinte teatrali; al contrario, agiscono sull’animo umano e possono veicolare significati profondi. La casa della propria infanzia, la soffitta, la cantina: ognuno di questi luoghi possiede una storia che ci precede e affonda le sue radici nell’inconscio collettivo. Bachelard sottolinea poi un altro aspetto cruciale, che riguarda il ruolo dello spazio nella creazione dei ricordi. Mentre il senso del tempo è soggetto a continue deformazioni – percepiamo la durata in modo soggettivo e tendiamo a modificare la cronologia – la collocazione spaziale è ineludibile. I ricordi restano custoditi saldamente all’interno del loro involucro tridimensionale. Separare tempo e spazio è un’impresa impossibile. “Lo spazio, nei suoi mille alveoli, racchiude e comprime il tempo”, scrive il filosofo francese. E i ricordi sono “tanto più solidi quanto più e meglio vengono spazializzati”. Le intuizioni di Bachelard sono molto utili per comprendere la natura delle immagini nel mondo delle “estetiche di internet”, movimenti culturali che nascono online e ruotano attorno alla creazione collettiva di universi visivi e sonori. Sul web, ogni estetica ha caratteristiche specifiche: diventa riconoscibile attraverso l’uso di colori, forme e ambientazioni, creando un template di base di volta in volta reinterpretato da utenti diversi. Estetiche molto popolari come la vaporwave, il dreamcore e il weirdcore sono emerse dalla rielaborazione collaborativa di immaginari, stili ed elementi culturali eterogenei. La loro propagazione segue le regole della memetica, ossia procede per imitazione e variazione, generando una vasta nuvola di contenuti simili ma mai identici, collegati tra loro da una rete di connessioni formali ed emotive. Le estetiche di internet, in sostanza, sono tenute insieme da un meccanismo di risonanza; puntano a connettere spazi interiori attraverso la stimolazione sensoriale, psichica, immaginativa. Si tratta di artefatti culturali che non sono destinati alla contemplazione quanto alla stimolazione: ciò che conta è la loro capacità di trasmettere emozioni, vibrazioni e stati mentali. Questa idea della risonanza ha molto in comune con il concetto di retentissement di cui parla Bachelard nel suo saggio. Descrivendo le dinamiche in atto tra poeta e lettore, il filosofo francese spiega come certe descrizioni di luoghi possano evocare immagini dal valore archetipo, in grado di raggiungere l’altro nel profondo della sua psiche, rompendo i confini della soggettività. Il lettore, insomma, può provare ripercussioni sentimentali profonde che sono attivate tramite richiami diretti al proprio passato. Immagini che vengono dal vissuto altrui possono evocare ricordi e riattivare emozioni, lasciando intravedere l’accesso al grande bacino della coscienza collettiva. All’interno del vasto universo delle estetiche di internet, c’è un genere d’immagine che sembra possedere un grado particolarmente alto di risonanza; riemerge infatti da oltre un decennio, come un filo conduttore sotterraneo, in universi estetici sempre diversi. Si tratta degli spazi liminali (liminal spaces), ossia fotografie che rappresentano luoghi di passaggio, zone di transizione, oppure semplicemente ambienti deserti. Il concetto di liminalità, definito e studiato da antropologi come Arnold van Gennep e Victor Turner nel secolo scorso, nasce inizialmente per descrivere uno stato sociale o psicologico. Fa riferimento agli esseri umani e non ai luoghi. In Il processo rituale (The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, 1969), Turner scrive ad esempio che “gli esseri liminali non sono né da una parte né dall’altra, stanno in uno spazio intermedio (betwixt and between) tra le posizioni assegnate e distribuite dalla legge, dal costume, dalle convenzioni e dal cerimoniale. In quanto tali, l’ambiguità e l’indeterminatezza dei loro attributi trovano espressione in una ricca varietà di simboli nelle numerose società che ritualizzano le transizioni sociali e culturali. Per esempio, la liminalità viene spesso paragonata alla morte, al fatto di essere nell’utero, all’invisibilità, all’oscurità, alla bisessualità, al deserto e a un’eclissi solare o lunare”.

La liminalità è dunque un luogo interiore prima ancora che fisico, e può essere descritta come un senso di so-

A CONVERSATION BETWEEN

AND

Krystian Lupa is pure European theatre straddling two centuries. A gentle man who drinks coffee in a large twentieth-century porcelain cup and mentally writes a manifesto about catastrophe, a list of options for future suffering, between shipwreck and concealment