‘AND

‘AND

Foreword

Lidewij de Koekkoek

Introduction

Epco Runia

At Home with Rembrandt

Leonore van Sloten

Rembrandt’s Personal Circle

Epco Runia

EARLY FRIENDS

Jan Lievens

Constantijn Huygens

Friends, with Different Networks

Lloyd DeWitt

BLOOD FRIENDS

Saskia Uylenburgh

Hendrick Uylenburgh

Jan Cornelisz Sylvius

Titus van Rijn

Hendrickje Stoffels

Karel van der Pluym

A Network in Line: Rembrandt’s Portrait Etchings

Stephanie Dickey

‘Cousin’ Karel van der Pluym and the Benefit of Family

Marieke de Winkel

SOCIOGRAM

ARTIST FRIENDS

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Roelant Roghman

Philips Koninck

Jan van de Cappelle

Johannes Lutma

Christiaen Dusart

Jeremias de Decker

Rembrandt’s Artist Friends

Volker Manuth

Drawing Together Outdoors

David de Witt

CONNOISSEURS

Jan Six

Thomas Asselijn

Rembrandt in Friendship Books

Judith Noorman

A Painter Goes to the Rabbi

Jasper Hillegers

FRIENDS IN TIMES OF NEED

Lodewijk van Ludick

Pieter de la Tombe

Abraham Francen

Rembrandt’s True Friends

Maartje Veringa and Epco Runia

Lenders to the Exhibition

Notes

Literature

the Guild of St Luke—the artists’ trade body—agreed that it did not resemble the sitter. Otherwise he would try to sell the painting himself. Regrettably, we do not know which painting it was or how the dispute ended, but the story shows that Rembrandt was a determined man who did not readily doubt his abilities as an artist.

The art in the building served more than just business purposes. Rembrandt’s love of and fascination with the work of specific painters was almost certainly his overriding reason for collecting art. An inventory of Rembrandt’s possessions was made in 1656 because he had gone bankrupt. It shows that he owned several paintings by particular artists. Three painters stood out: Hercules Segers, Adriaen Brouwer and Jan Porcellis. Rembrandt greatly admired the work of these pioneers, who by coincidence had all died during the

sixteen-thirties. They were his heroes when he was growing up.

Rembrandt hung paintings of the same type together in groups. In the summer of 1656, for example, a Rembrandt tronie (character head) hung in the anteroom next to one by Brouwer.6 Landscapes by Segers, Jan Lievens and Rembrandt were also hung together in the front part of the house.7 In all probability Rembrandt shared his ideas with artist and art lover friends in front of such groups of artworks. Conversations like these would have been important to Rembrandt and his associates and might have influenced their own artistic development.

In the salon (sael) (fig. 2), at the back of the house on the ground floor, there were even more paintings. The walls were covered in them. The room on the first floor, directly above the salon, was used as Rembrandt’s cabinet (kunstcaemer) (fig. 3). This is where he kept his exotic objects, casts of

classical statuary, medals and stuffed animals. Here, too, was Rembrandt’s valuable collection of thousands of drawings and prints—his own drawings but chiefly works on paper by artists he admired. Rembrandt would have examined and discussed this collection with good friends, art lovers, collector friends and pupils.

There was a large kitchen in the basement at the rear of the house. The people living in the house met there to have meals. The pupils probably ate there too. They were in the house during the day but we assume they did not live there. The kitchen would have been a busy place, where all the household activities were organized. It was the scene of an argument on 10 October 1649. During negotiations about a dispute between Rembrandt and his former maid Geertje Dirckx, emotions escalated to such an extent that she let

fly ‘very fiercely and unreasonably’ at Rembrandt during an exchange in the kitchen.8

Most of Rembrandt’s family’s time was spent in the salon. This dignified room on the ground floor, above the kitchen, was used a living room, and the man and lady of the house slept there at night. It was where Rembrandt and his wife Saskia had their happiest and their saddest moments. It is probably where Saskia gave birth to their son Titus in September 1641. The following year, at the age of twentynine, Saskia died there on 14 June.9 Hendrickje Stoffels became Rembrandt’s life partner in 1649. She gave birth to their daughter Cornelia in the house in Jodenbreestraat in October 1654.10

Rembrandt spent many hours in the large studio (groote schildercaemer) (fig. 4). When not dealing with pupils

1. Rembrandt Portrait

Oil on panel, 99.5 x 78.8 cm

Kassel, Museumlandschaft Hessen Kassel

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

If you search Rembrandt’s oeuvre for the faces of his family and friends, it will not be long before you have a list of more than thirty paintings. Members of Rembrandt’s immediate family top the list. There are, for instance, at least five paintings of his wife, Saskia, seven of his later love, Hendrickje, and no fewer than eight of his son, Titus. Some other members of the family and several of Rembrandt’s friends are portrayed once or twice. It is a unique phenomenon in the seventeenth century – an artist who recorded the likenesses of his friends and loved ones so often and usually in a very informal and intimate way. Why did he make these paintings? And what do they tell us about Rembrandt’s relationship with the people in his personal circle?

It is by no means always easy to recognize members of Rembrandt’s family and his friends in his paintings. Although we have a reasonably good idea of what Saskia looked like, for example, there are still arguments about whether she is or is not pictured in a particular work.1 An added complication is that Saskia’s face was the inspiration for a facial type that Rembrandt often used.2 In truth, almost all Rembrandt’s ideal women look like Saskia to some extent, without actually being her. Nevertheless, there are five paintings that everyone agrees are of Saskia. He seems to have made some of them as a tribute to his wife; one such is the portrait now in Kassel (fig. 1). It shows Saskia in a magnificent, elaborate fantastical costume of crimson velvet, fur and a spectacular wide-brimmed hat with an ostrich plume. She appears in profile, deep in

thought. The portrait is dignified and restrained, but has great visual richness; it is a distinguished portrait that does justice to Saskia’s well-bred origins. As far as Rembrandt was concerned, this painting must have been an important personal project. He worked on it over a period of almost ten years, roughly from when he became engaged to Saskia (1633) until her death (1642) and he always kept the painting in his home.3 It was not until thirteen years later, when he was up to his neck in debt and in urgent need of money, that he sold it to his good friend Jan Six I. Even then, though, Rembrandt could not let it go altogether and he got his pupils to make a free copy of it (see page 41). He kept this copy with him in memory of his great love, whom he had lost so tragically young.

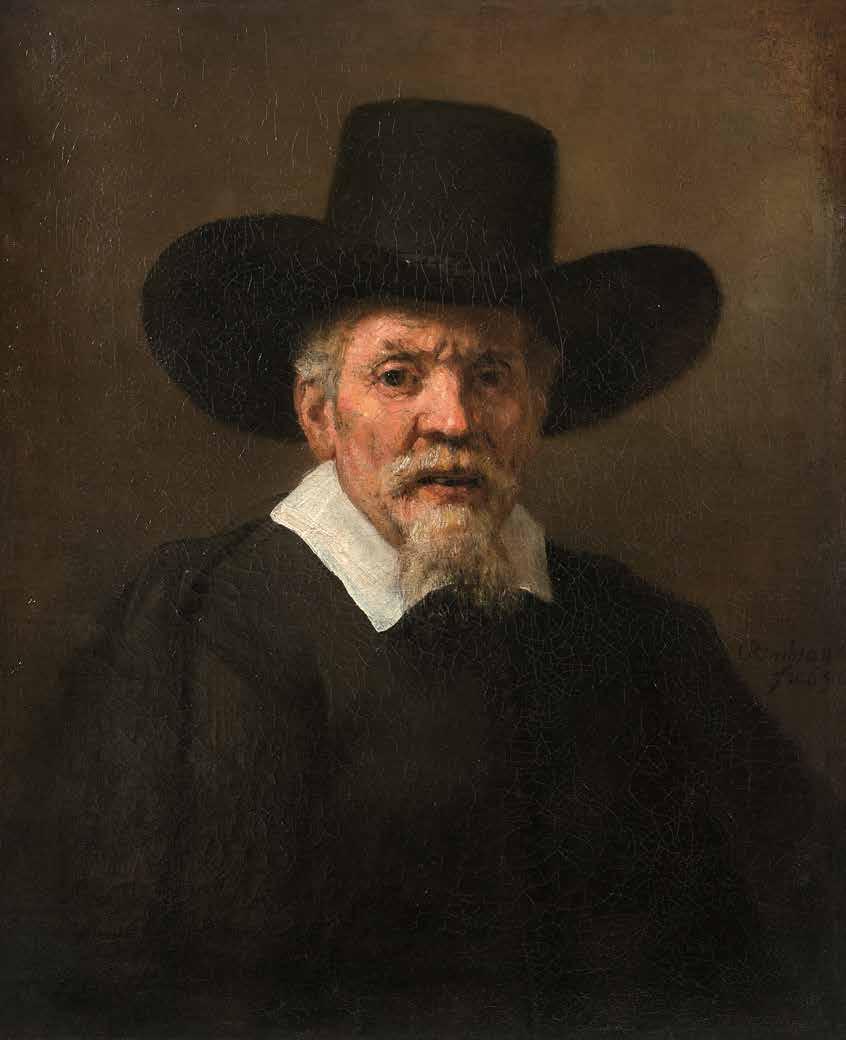

6. Rembrandt

Portrait of Arnold Tholinx, 1656

Oil on canvas, 76 x 63 cm

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André

father and son. Titus was relaxed in his father’s company. Father and son seem to get on well; they were comfortable with one another.

The portraits Rembrandt painted of his friends are often much more informal than the ones he made for official clients. Jan Six I’s is not just the most famous, it is the largest and most ambitious (fig. 4). But then, Six was not an ordinary friend; he was a connoisseur of art with a very deep purse. The large size notwithstanding, Six is pictured in a very informal situation, drawing on his gloves as he prepares to go out. Rembrandt seems to have developed a simpler template for portraits of other friends. These works are smaller, and the sitter is often quite tightly framed so that less of the setting can be seen.4 In 1656, for instance, Rembrandt made one such simple portrait of Arnold Tholinx (fig. 6), an eminent physician and the brother-in-law of Rembrandt’s friend Jan Six I.5 In the same year, Tholinx also commissioned a portrait etching from Rembrandt and must have been a fan of his work. What makes these rather sober friends’ portraits so attractive is the concentration on the faces, in which Rembrandt always captured great expressiveness. In this instance, it is as if Tholinx, with his slightly parted lips, simply carried on talking while he was sitting to the artist. The deep frown suggests that this was not an easy conversation, and certainly none too cheerful.

The template of the friend’s portrait, particularly the tight framing, can also be identified in the portrait of an elderly man in The Hague (fig. 5). The man’s identity is unknown, but the painting’s understated composition and the unusually informal impression it makes leaves no doubt that he must have been at least a close acquaintance of Rembrandt’s. The man sits a little awkwardly in his chair and seems to be seeking support from the armrests with his hands. His collar hangs open and his hat is crooked on his head. Rembrandt used much cheaper, poorer quality materials than usual and made the painting quite hurriedly: the greenish-brown ground is still visible in many places and he scratched away in the

paint with abandon to indicate the hair and other elements. The result is none the worse for it. You get the impression that the man was captured in an unguarded moment, perhaps during a convivial evening with the artist. The mood consequently appears more pleasant than in Tholinx’s portrait. Does this also mean that he had a better relationship with Rembrandt? it could be. It has been suggested that the man was the seventy-four-year-old bookseller and art dealer Pieter de la Tombe, who is known to have been one of Rembrandt’s best friends and owned a portrait Rembrandt had painted of him ‘in his old age’.6

Although painters like Jan Steen and Gerard ter Borch sometimes used their relatives as models, there is only one other artist in the seventeenth century who, like Rembrandt, regularly painted his family and friends. This was Rubens.7 It is possible that this earlier Flemish predecessor was actually a source of inspiration for Rembrandt in this respect. However, Rubens’s compositions are rather more considered than Rembrandt’s and his technique is not as free and sketchy, so that Rembrandt’s paintings seem to have come about more spontaneously. Rembrandt had a better sense of the mood of the moment and the sitter’s feelings, even when they are not really animated. It is, in short, as if we, the viewers, are let in on the special bond between the artist and his loved ones. And in this, Rembrandt is unique.

Saskia Uylenburgh (1612-1642)

Saskia was daughter of the prominent lawyer Rombertus Uylenburgh, who rose to the highest positions in Friesland: pensionary and High Court jurist, and burgomaster of Leeuwarden.1 He was notably the last visitor of William of Orange just before his assassination. After his death in 1624 his young daughter Saskia followed her sister Hizkia and her husband Gerrit van Loo, who became her guardian, when they settled in the northern town of Sint Annaparochie in 1627.2 In 1633, she visited her cousin Aeltje Uylenburgh in Amsterdam.3 In that year her husband the Reformed preacher Johannes Silvius was having a portrait etching made by Rembrandt, working in the house and studio of another cousin, the portrait broker Hendrick Uylenburgh.4 This may have been the occasion for her to meet the successful young artist. They were engaged in June,5 and married a year later, living at the house in the Jodenbreestraat until 1635.

Rembrandt painted many portraits of Saskia and incorporated her likeness in various history and genre scenes, attesting to an affectionate and respectful relationship. She bore him four children, of whom only the last one, Titus, survived infancy. During these years the Uylenburgh family figures prominently in Rembrandt’s life, but not always without tension. They expressed concern about the management of her inheritance,6 and in her last testament she stipulated that Titus receive his entitlement as soon as Rembrandt remarried.7 In 1642 she succumbed to illness, thought to be tuberculosis, just as Rembrandt was completing the Night Watch

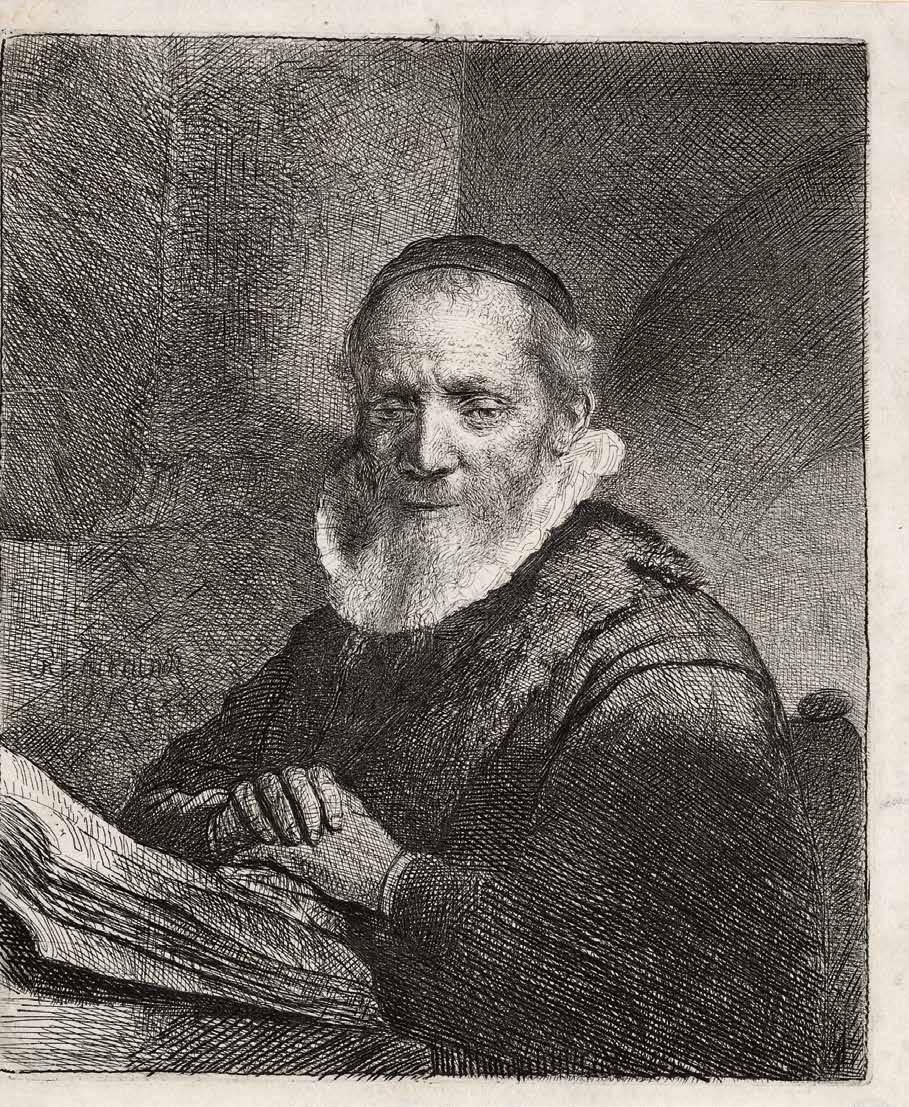

Jan Cornelisz Sylvius (1564-1638)

Sylvius was a Calvinist preacher who belonged to Rembrandt’s in-laws by his marriage to Aeltje Uylenburgh in 1595. They lived in Amsterdam since 1610, and there the couple welcomed their orphaned cousin Saskia in 1633.1 Sylvius witnessed the banns of Saskia’s marriage to Rembrandt in 1634, and the baptism of two of their children, before his death in 1638. Rembrandt painted a stunning and vibrant portrait of Sylvius’s aged wife in 1632, as well as a pendant of him that has been lost.2 This etching of him from the following year is by contrast more reserved, with the sitter striking a meditative pose, his unfocused gaze falling to the right, his hands clasped. He chose a setting and pose from existing images of scholars in their studies, in particular the famous engraving of Erasmus by Dürer.3 The column symbolised strength, which here would refer to the preacher’s important role as a spiritual leader of three congregations in succession.4 He wears a tabbaard, an old-fashioned sleeveless, fur-trimmed gown favoured by his profession.5

Portrait prints of preachers were not uncommon: they were distributed among followers and colleagues and regularly displayed in their homes as signs of allegiance. Rembrandt would go on to produce several etched portraits of preachers, including a posthumous print of Sylvius, in a more dynamic oratory pose and with a lengthy inscription, in 1646.6

e

Hendrickje Stoffels (1626-1663)

Dutch literature of the Golden Age repeatedly warned about ‘the sexual threat’ that servant girls posed to the fathers of households.1 Rembrandt faced this kind of trouble with two young women who came to help after the death of his wife Saskia in 1642. The second of these was Hendrickje Stoffels (or Jegher), daughter of Sargeant Stoffel Jegher from Bredevoort, near Arnhem. Around 1649, Rembrandt began an amorous relationship with her that became a kind of second marriage.2 It was never legally formalized however because of the financial requirements of Saskia’s last testament.3 With their combined wealth invested in an illiquid collection of art and curiosities, he could not pay Saskia’s part of the inheritance to Titus, as she required, if he were to remarry.4 Cornelia, daughter of Rembrandt and Hendrickje, was born in 1654 and named after Rembrandt’s mother. The pregnancy was likely the prompt for the Reformed Church to censure their non-marital relationship, as ‘whoring’.5

Rembrandt depicted Hendrickje in many works of art, including some of the great monuments of his oeuvre, as Bathsheba, a Courtesan, and Callisto.6 After the insolvency was complete in 1658 Hendrickje also came to play a business role in Rembrandt’s life. In order to shield themselves from his creditors, she established an art dealership jointly with Titus through which Rembrandt’s work would be sold. Hendrickje died suddenly in 1663 when the plague swept through Amsterdam.7

e

Christiaen Jansz Dusart (1619-1682)

Christiaen is best known for his role in the last decade of Rembrandt’s life. He was witness to Hendrickje’s testament in 1661, and after her death Rembrandt appointed him guardian of their daughter Cornelia.1 In 1668 he lent the artist 600 guilders.2 But he may have known Rembrandt longer, since the 1640s. His painting of A Young Scholar by Candlelight is dated 1645 (see opposite) and points to possible tutelage under the master during this period. In 1642, Christiaen married the writer Catharina Verwers. Rembrandt’s intriguing etching of The Spanish Gypsy may have been prompted by her play adaptation of Cervantes’ written around the same time and published in 1644.3

Christiaen Jansz Dusart was born into a Mennonite family in Antwerp in 1618, that moved to Utrecht around 1621, and to Amsterdam in 1628.4 He and his brother Isaak became painters, although his chief source of income may have been cloth dying. His cousin Cornelis studied under Adriaen van Ostade and became a prominent genre painter and printmaker in Haarlem.5 Christiaen painted genre and still lifes, and in the 1650s turned to portraiture. He spent several years in London (1654-1655) and The Hague (1664-1665) but the couple maintained their residence in Amsterdam on the Botermarkt (now Rembrandtplein), not far from Rembrandt’s House on the Jodenbreestraat.

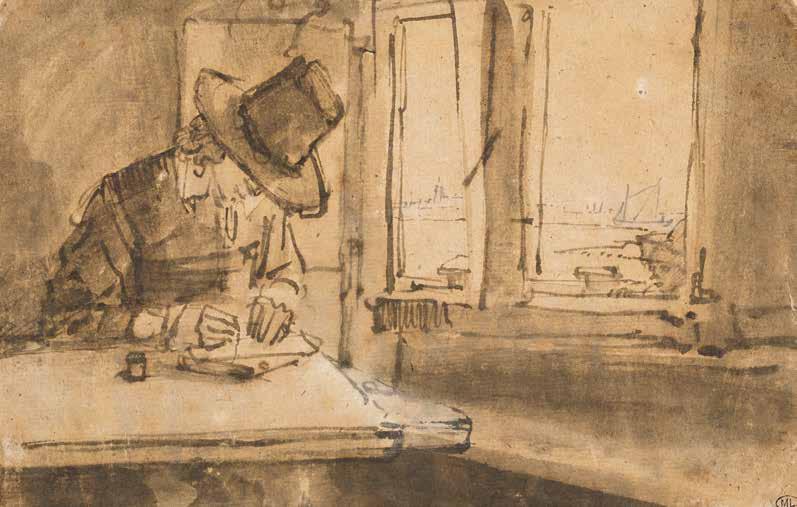

Over the years Rembrandt visited many sites in and around the city of Amsterdam. We know this because he made fairly accurate topographical drawings.1 The artist made this one of his main leisure activities. He evidently could not stop making art. At the same time, landscape drawing also appears to have been a platform for friendship. This suited an artist not known for frivolity, or excessive socializing.

DAVID DE WITT

2. Abraham Furnerius

The Bulwark Rijzenhoofd, 1645-50

Pen in brown, brush in brown and grey, 201 × 315 mm. Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum

A number of places in the countryside around Amsterdam have already long been identified in drawings and etchings by Rembrandt: the Omval, Huis Kostverloren, and Six’s Bridge. But it was only in the twentieth century that it became clear that one can follow specific walking routes outside the city in Rembrandt’s landscape etchings and drawings.2 Such walks were an established leisure activity, and already around 1607 the Amsterdam printmaker and publisher Claes Jansz Visscher had started making numerous drawings of sites outside the city, with the aim of publishing prints after them.3 His series of views around Haarlem, entitled ‘plaisante plaetsen’ (pleasant places), is his most famous in this genre.4 Educated gentlemen would have known of the tradition of poetry about the beauties of the countryside that went all the way back to ancient Rome. Generally, Rembrandt followed the

same routes as Visscher, but he found many more picturesque views to draw. 5 It is fascinating that we can follow his progress along the Diemerdijk, for instance, from one farmstead to another.6 The recreational nature of these walks is confirmed by the conspicuously large number of tap houses along these routes. Indeed, it is in one such establishment that Rembrandt drew an artist companion at his sketchbook (fig. 1).7 The view out the window clearly shows the ships tie-downs on the IJ at the cutoff from the Diemerdijk to Diemen, where several tap houses stood.

The detailed drawing of the impressive mill on Rijzenhoofd, a bulwark poking out from the northeast corner of the city, came from the hand of Abraham Furnerius (fig. 2).8 We know Furnerius was in Rembrandt’s studio in the early 1640s.9

1. Rembrandt

Portrait of Ephraim Bueno, 1647

Etching, 211 x 163 mm

Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum

Two outstanding representatives of their own cultures: Rembrandt and the distinguished Sephardic rabbi, printer and publicist Menasseh Ben Israel (1604-1657). Menasseh was a Marrano – a Portuguese Jew born on the island of Madeira and forced to convert to Christianity – who arrived in Amsterdam with his family around 1613.1 For centuries it has been assumed – and wished – that they were friends. To be absolutely clear, though: there is no seventeenthcentury documentary evidence that links Rembrandt and Menasseh. The notion of their friendship appears to rest primarily on three mutually reinforcing artistic pillars, which simultaneously suggest a time span (and hence a lengthy connection): they are a Hebrew inscription on a Rembrandt painting dating from around 1635, a 1636 portrait etching and four Rembrandt etchings in several copies of a book written by Menasseh in 1655. Although these pillars have long supported this link, the facts prove less compelling than is often suggested.

The bond between Rembrandt and Menasseh Ben Israel was situated against the background of the neighbourhood in which they lived – around present-day Jodenbreestraat – and fuelled by Rembrandt’s supposed sympathy for the Jewish people, underpinned by his portrait of the Jewish physician Ephraim Bueno, who supported Menasseh’s Hebrew publishing house financially (fig.1). Now and then imagination has coloured the stories. In his biography of Rembrandt (1836) the art dealer John Smith, for example, suggests that the artist’s association with the ‘Kabbalah enslaved’ Menasseh and Bueno led to his bankruptcy, because he squandered his money on alchemistic practices at their instigation.2 In the post-war novel Rembrandt vorst der schilders we read

how Menasseh sent his maid to his close friend’s house with a tender chicken when Rembrandt’s wife Saskia lay ill in bed. Even art historians subscribe to the idea of this special relationship between the painter and the rabbi.3 In the last few decades, however, their relationship has been questioned and new insights remain the subject of ongoing discussion.4

HEBREW DIAGRAM

The first ‘pillar’ is a wonderful Old Testament painting by Rembrandt, in which the Babylonian king Belshazzar lays on a feast with treasures looted from the temple in Jerusalem (fig. 2). This blasphemy costs dearly: during the orgy of eating and drinking, God’s hand appears and writes a mysterious