Preface 6

by Anna Cerboni Baiardi

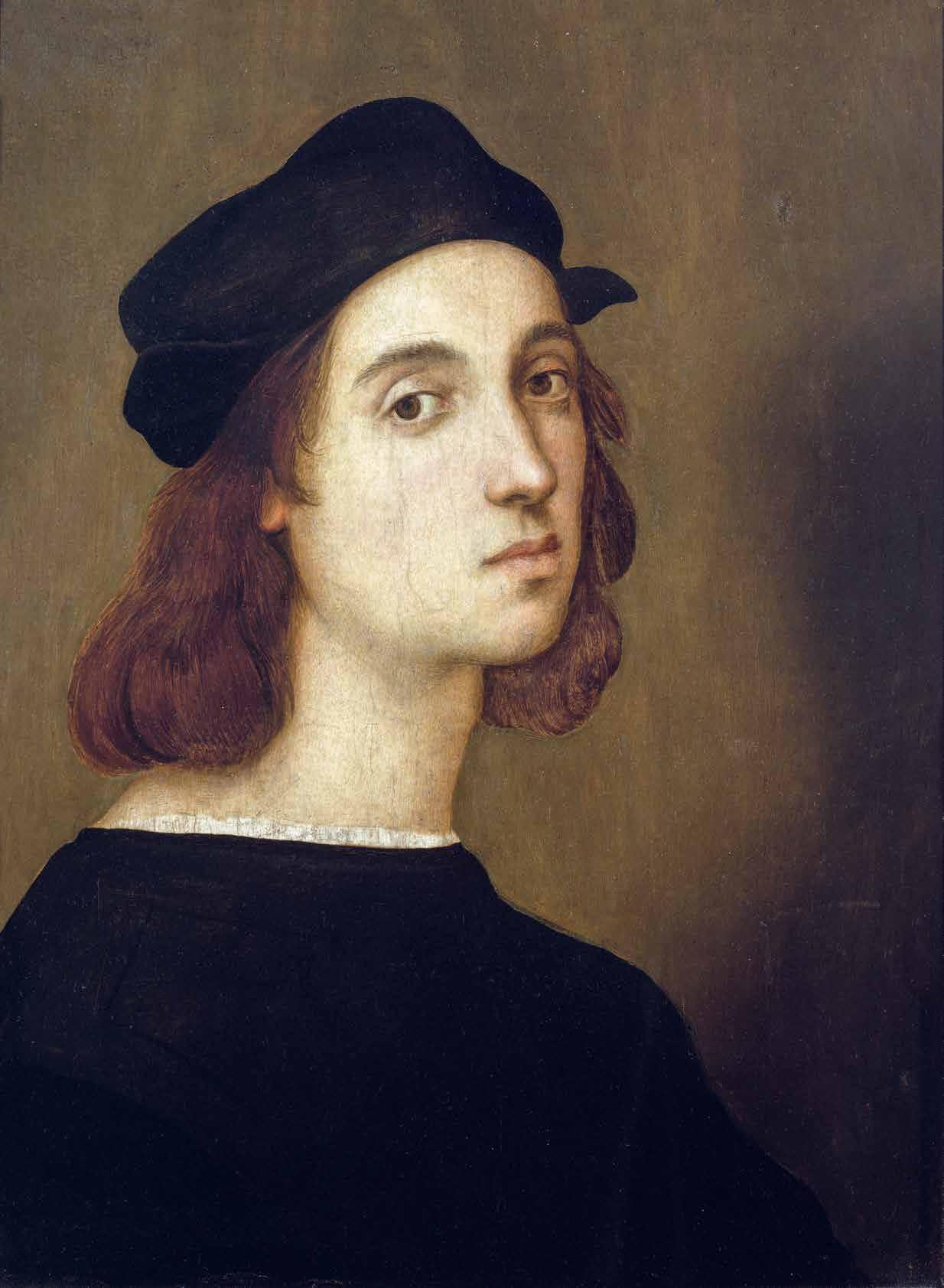

The Life of Raphael According to Giorgio Vasari 8

by Anna Cerboni Baiardi

The Myth 34

by Anna Cerboni Baiardi

The Early Works 46 by

Monica Grasso

The Frescoes in the Raphael Rooms 72 by

Monica Grasso

Raphael, Painter of Madonnas 136 by

Monica Grasso

Raphael and Agostino Chigi 158 by Monica Grasso

Raphael the Portraitist 180 by Cecilia Prete

The Last Works 220 by Monica Grasso

suggesting that he and Raphael worked together as equals.

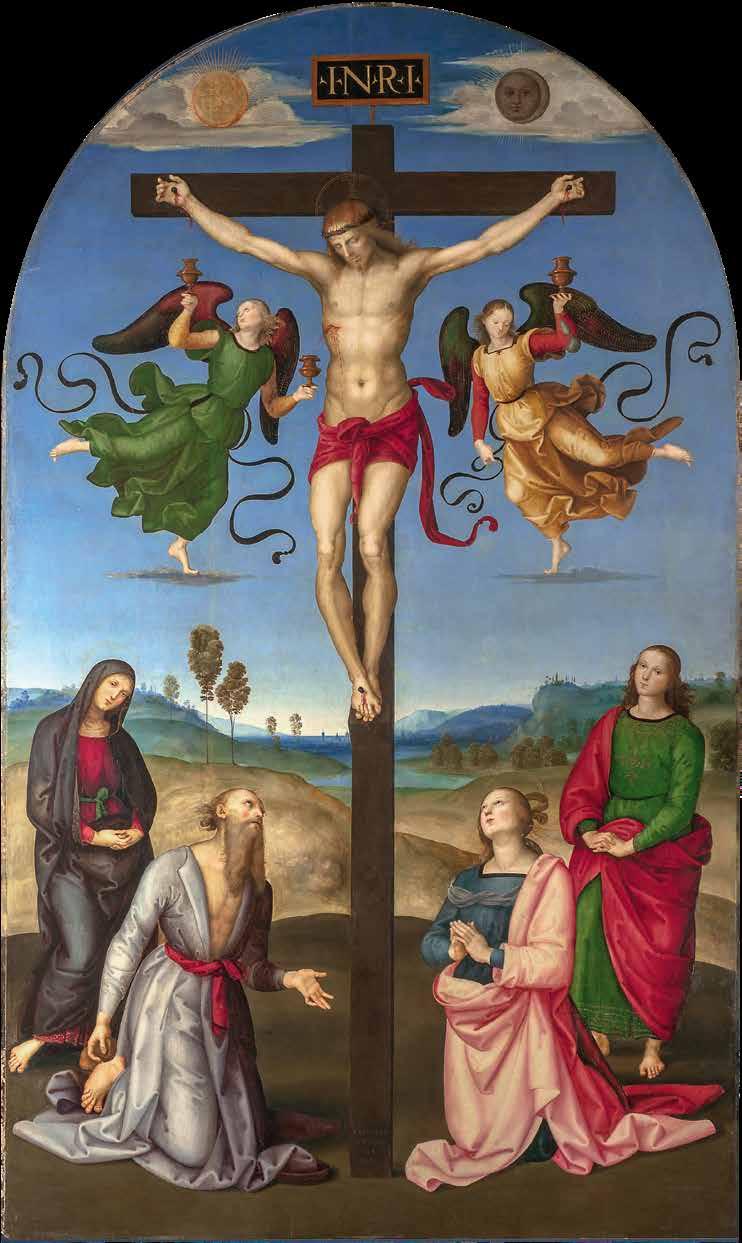

In truth, Vasari used the relationship between Pietro and Raphael as a means of gauging the incredible development of the young Urbinate and making a distinction between his first and second manner: despite his tender age, Raphael was making a giant leap forward and aimed at equaling his teacher. This is evident in The Mond Crucifixion (1502–1503) in the National Gallery of London, painted for the Gavari Chapel in San Domenico Church at Città di Castello (where Raphael was “with some friends” on his own while, in the meantime, Perugino had gone to Florence), or in the Oddi Altarpiece (c. 1503), commissioned by the Oddi family for the Church of San Francesco in Perugia and now kept in the Vatican Pinacoteca.

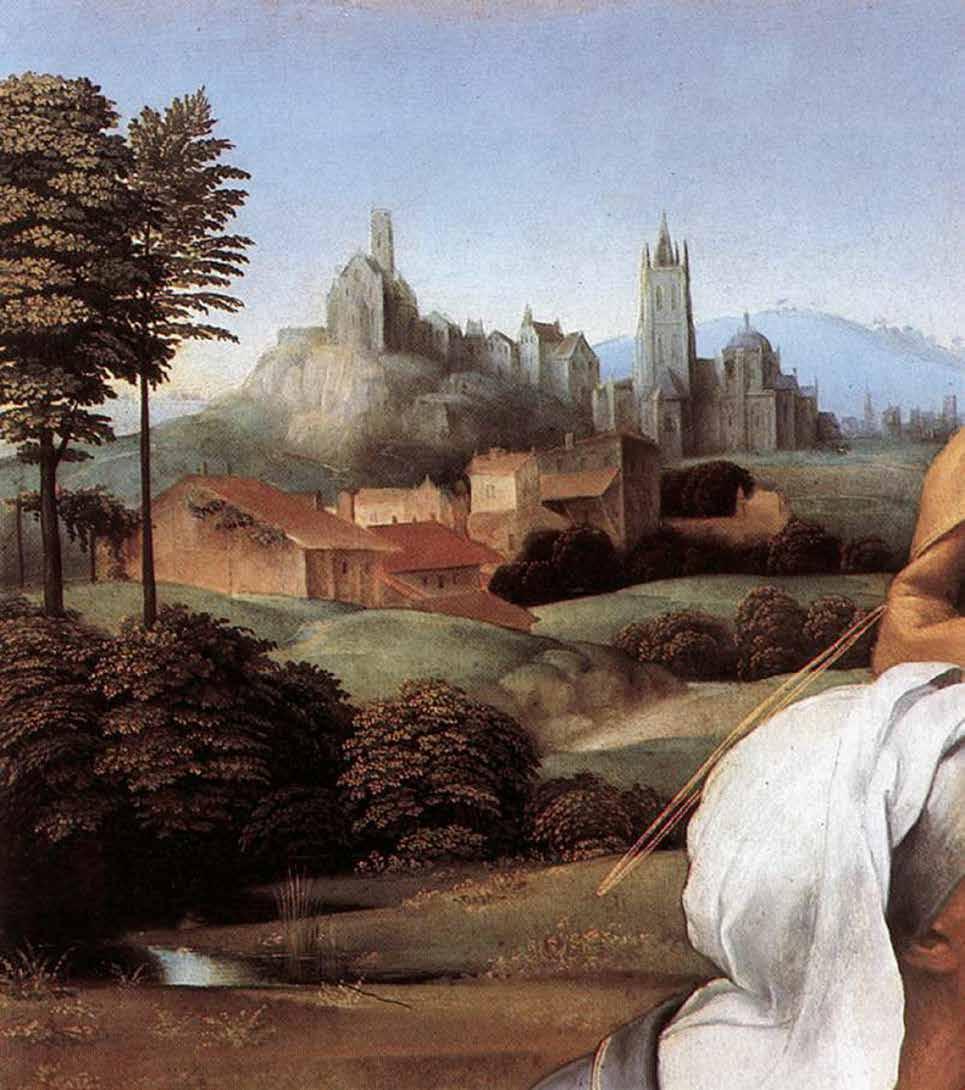

Vasari goes on to state that, thanks to the young artist’s observation of Leonardo’s art, the pupil would surpass his teacher in a series of progressive steps forward that led to the creation of The Marriage of the Virgin (1504; now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan). This work was commissioned by the Albizzini family for the Chapel of St. Joseph in the Church of San Francesco in Città di Castello, and Vasari’s glowing comment is as follows: “In this work is a temple drawn in perspective with such loving care, that it is a marvelous thing to see the difficulties that he was forever seeking out in this branch of his profession.” This was only the beginning, as the young artist’s insistent and evident study of perspective in that moment must have animated his mind to no little degree.

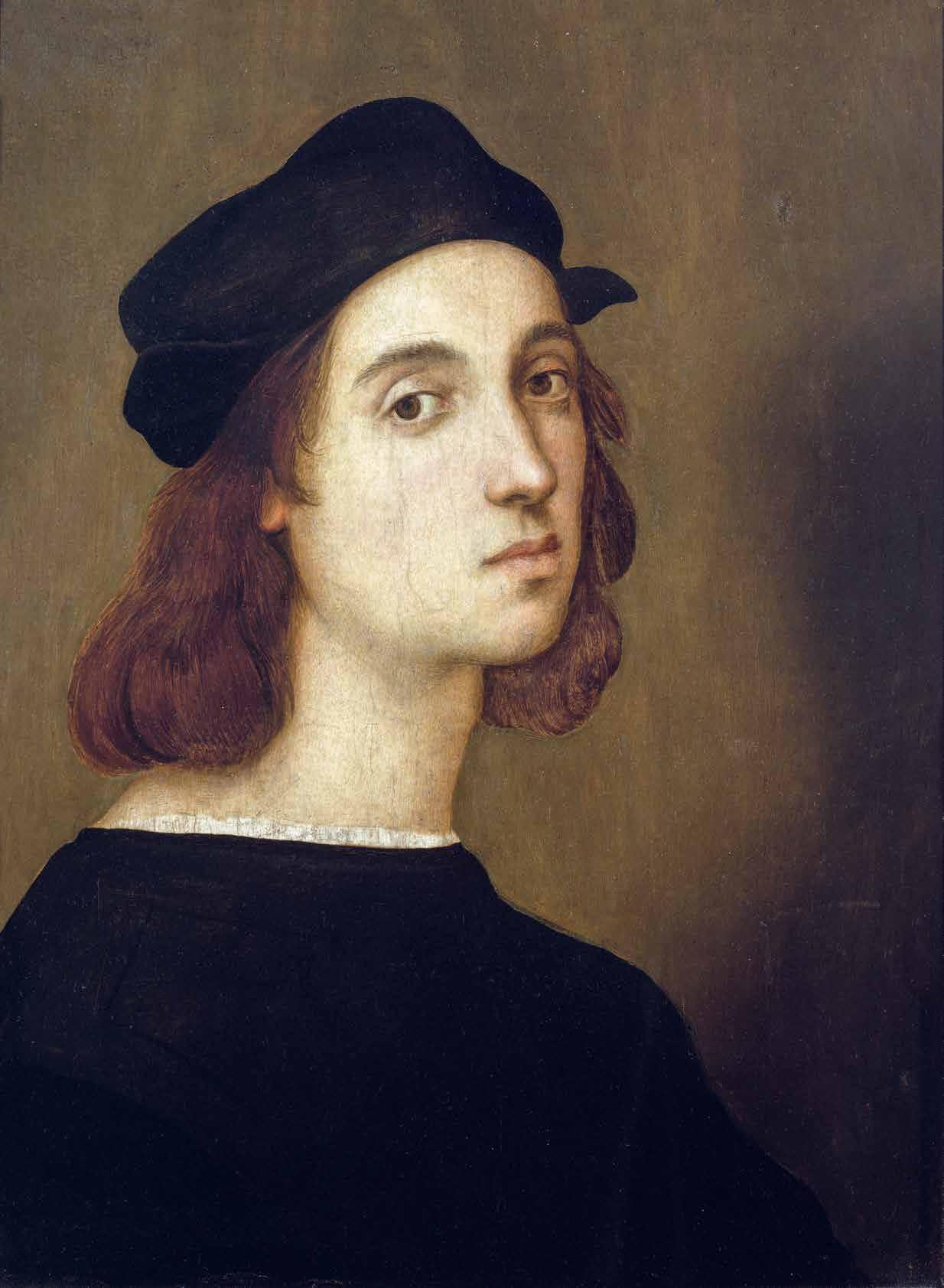

His stay in Florence is one of the most crucial moments in his life. The beginning of this period is usually dated sometime in late 1504, in consideration of a letter written on October 1 that same year by Giovanna Feltria Della Rovere, the sister of the Duke of Urbino, Guidobaldo, in which she highly recommends the 21-year-old to Pier Soderini, gonfalonier

or standard-bearer of the Florentine Republic. Vasari does not mention this letter, the authenticity of which has been doubted by some art historians. As a matter of fact, he places the beginning of Raphael’s “Florentine period of study” at the time when he left Siena after his work on the Piccolomini Library side by side with Pinturicchio and rushed to Florence to study the famous cartoons of the victories of the Florentine army that would inspire entire generations of artists: the Battle of Anghiari and the Battle of Cascina. In 1503, the above-mentioned Pier Soderini had entrusted these works to Leonardo and Michelangelo respectively, as part of the new decoration of the Salone dei Cinquecento, or Hall of the Five Hundred, in Palazzo Vecchio.

In fact, on 29 June 1502 Pinturicchio—one of the leading painters of the Umbrian Renaissance, known for his skill in the use of vibrant colors and narrative—had stipulated with Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini Todeschini a contract for the decoration of the library dedicated to his uncle Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini), which was to house the pope’s splendid collection of books. Work on the frescoes, the principal sections of which depict the major episodes in the life of Pius II, probably began sometime between 1502 and 1503 and were suspended after Piccolomini Todeschini’s death, which occurred on 18 October 1503 (only 26 days after his election as pope under the name of Pius III) and were concluded around 1507, or 1509 according to some art historians.

Vasari states that Raphael was involved in this project thanks to his being an “excellent draftsman,” something that Pinturicchio knew quite well, since the two had a longstanding friendship. Raphael’s precociousness, his inventive gifts and compositional skills, and his ability in creating such admirable drawing and painting, were all well known to everyone, for that matter—since, as early as 1500, when he

The Mond Crucifixion (Crucifixion with Two Angels, the Virgin and Three Saints), 1502–1503, oil on panel, 280 x 165 cm (110 x 65 in.), signed RAPHAEL VRBINAS P., National Gallery, London

Friars and now in the National Gallery of London; the decoration of the upper section of the fresco in the church of the San Severo monastery depicting The Holy Trinity With Saints (1505), a brief Umbrian prelude to his great Roman fresco, the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament; and the Colonna Altarpiece (dated at around 1502) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, with the lunette commissioned by the Nuns of Sant’Antonio in Padua, who had asked that the Christ child be clothed.

The mention Vasari made of the portraits of Agnolo Doni— who was “careful of his money, but willing to spend it, although still with the greatest possible economy, on works of painting and sculpture, in which he much delighted”—and his consort allowed him to return to the subject of Florence.

Although the chronological order of the works Raphael executed in Umbria and Tuscany as related by Vasari does not always stand up to the evidence provided by modern art historians (and it is precisely here that he challenges history), we must pay special attention to him when he reflects on the importance the many works “by the hands of excellent masters” Raphael had seen in Florence, the artists “responsible” for his great progress: “I will not refrain from saying that it was recognized, after he had been in Florence, that he changed and improved his manner so much, from having seen many works by the hands of excellent masters, that it had nothing to do with his earlier manner; indeed, the two might have belonged to different masters, one much more excellent than the other in painting.”

Vasari clearly points out the superiority of Florentine art by naming some of Raphael’s contemporaries, first of all Leonardo and Michelangelo, as well as such eminent predecessors as Masaccio, whose memory can most certainly be seen in many of Raphael’s works, such as the preparatory cartoons for the

Vatican tapestries, which are overflowing with all the powerful volumes and stateliness of the protagonists in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, on the walls of which Masaccio, another genius who died prematurely, had established new stylistic standards in 1425.

This fundamental period ended with The Deposition, commissioned by Atalanta Baglioni in memory of her son Grifonetto in the church of San Francesco al Prato in Perugia (now in the Galleria Borghese, Rome), a work in which Raphael represented “the sorrow that the nearest and most affectionate relatives of the dead one feel in laying to rest the body of him who has been their best beloved, and on whom, in truth, the happiness, honor, and welfare of a whole family have depended.” Another major work was the large altarpiece intended for the Dei Chapel in Santo Spirito Church, the socalled Madonna del Baldacchino (1508), now in the Galleria Palatina in Florence, which Raphael never finished because he set out for Rome (“and he began it, and brought the sketch very nearly to completion.”): his first public commission in Florence. This panel contains everything that Raphael had become, everything he had pondered, the elements he would develop, and those that would have an obvious influence on the painters active in Florence at the time and in the following decades.

The Madonna and Child on the throne under the baldacchino, who are grouped in the semicircular space of an apse together with four saints (Peter, Bernard, James the Elder, and Augustine), immediately bring to mind Piero della Francesca’s Brera Madonna; but while in Piero’s sacra conversazione the architecture is behind the protagonists, Raphael places the figures inside it, here again anticipating what he would do in the Vatican fresco, The School of Athens. An overall soft quality mindful of Leonardo’s sfumato, as well as the play of glances utilized in the many Madonna and Child

compositions, connect the figures, one of whom intercedes for us with the Virgin The gestures delicately animate the celestial vision revealed by the angels lifting the curtains in a sort of prelude to the Sistine Madonna. Both angels later appeared in the same guise in the fresco with the Sibyls in Santa Maria della Pace Church in Rome, where Raphael was helped by his fellow Urbinate Timoteo Viti; and the one at left was taken up in Girolamo Genga’s Annunciation, in the lunette of the ancona painted for the church of Sant’Agostino in Cesena (1515–1518). The barely visible hand of St. Peter holding the book on his thigh was more or less mirrored in 1517 in the hand of the Madonna of the Harpies by the “faultless painter,” Andrea del Sarto, who also studied the play of the hands placed one over the other on the staff of St. James for his rendering of San Fedele di Como in the Assumption of the Virgin, executed in 1530. Lastly, the entire Madonna of the Baldacchino would be the basis of Fra’ Bartolomeo’s Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, executed in 1512.

Rome

Regarding Raphael’s move to Rome, which under the papacy of Julius II Della Rovere was developing into the driving force of art in Italy, Vasari singles out Donato Bramante—“distantly related” to Raphael “and also his compatriot”—who advised the young artist to come to the Eternal City because the pope was having some of the rooms in his palace decorated By mentioning the artists who had already worked there—Piero della Francesca, Bartolomeo della Gatta, Bramantino, and Perugino—Vasari was in fact envisioning a sort of competition between them and Raphael—a competition that the Urbinate won, since, after painting the first fresco, in which “he was resolved to hold the sovereignty” over the others, the pope ordered that “all the scenes of the other masters, both the old

and new,” be destroyed, entrusting the work to Raphael alone.

The account continues with precise descriptions of all the paintings Raphael executed in the Vatican for Julius II (1503–1513) and Leo X (1513–1521), from the first Stanza, known as the Room of the Segnatura, for which he received a first partial payment in January 1509, to the frescoes in the last one, the Room of Constantine, which were finished in 1524, after his death, by his assistants.

Vasari also mentions the Room of the Chiaroscuri, which Raphael decorated with the series of apostles and saints, which was already badly damaged in the mid–1500s and was entirely repainted (1560) by the Zuccari brothers. The author also lingers a bit in his description of the work done in the Loggias, commissioned by Leo X, where Raphael (who replaced Bramante) saw to the architectural design and also planned the painted and stucco decoration, with the help of excellent assistants.

Vasari also does not fail to mention the works that Raphael executed for other clients while he was working on the Vatican frescoes. In certain cases his comments are brief, in others more penetrating. He lists various portraits and other paintings that he will deal with in the following chapters, in the following order. First there is the Madonna of the Veil in Santa Maria del Popolo (well known now, thanks to replicas). Then come the works executed for the rich banker Agostino Chigi; The Madonna of Foligno for S. Maria in Aracoeli Church; the Madonna with the Fish for the Monastery of San Domenico in Naples; the Madonna of Divine Love commissioned by Leonello da Carpi; Ezekiel’s Vision for Count Ercolani of Bologna; the Madonna dell’Impannata, which he sent to the Medicis in Florence; Christ Falls on the Way to Calvary, executed for the monks of the Monte Oliveto Monastery in Palermo; and St. Michael Vanquishing Satan for the king of France, which

40 - Raphael Correcting the Pose of His Model, Alexandre Évariste Fragonard, 1820, oil on canvas, 140 x 87.5 cm (51 x 34 2/5 in.), Musée Fragonard, Grasse

41 - Raphael Teaching Perspective to Fra’ Bartolomeo, Filippo Leonardi, 1863, oil on canvas, 147.8 x 107 cm (58 x 42 in.), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Genoa

and now saw other greatly talented artists at work. Sandro Botticelli was still active, and Fra Bartolomeo, an artist who was a follower of Savonarola and became a monk at the San Marco convent and was to have a major influence on Raphael, was rapidly becoming well known. But above all, the city was passionately witnessing the battle between two titans taking place on the walls of the Sala del Gran Consiglio of Palazzo Vecchio, where Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were busy planning The Battle of Anghiari and The Battle of Càscina frescoes, works that contrasted two artists with wholly different temperaments and artistic stances. Again, in 1501 Leonardo had exhibited a cartoon, a preparatory study for the oil painting of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, which combined compositional virtuosity and a new psychological and expressive sensibility, while a few years later Michelangelo finished the Tondo Doni, in which the human figure acquires new monumentality and grandiose plastic qualities.

After viewing these powerfully innovative works, Raphael

abandoned both the final phase of 15th-century rigidity and the measured but static harmony of Perugino, and proceeded to embrace a more dynamic and expressive style as well as chiaroscuro to enhance the volumes, but without losing sight of his specific inborn qualities. This breakthrough is clearly seen in the beautiful figure of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507–1508, National Gallery, London), who moves with a delicate torsion, distancing herself from the landscape in the background, an intense expression on her face. The results of this evolution, which marked the end of his Florentine period, were works such as the Deposition, painted in 1507 for the Perugian noblewoman Atalanta Baglioni, and The Canigiani Holy Family, datable to 1507–1508. Both of these paintings reveal the explosive talent of a greatly matured Raphael, who was able to compete with the pictorial genius of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci without absorbing it wholesale as has sometimes been said, but rather pursuing his very own path and style, now ready to tackle the most prestigious commission of his life, the frescoes in the Vatican Stanze.

The Heads of Two Apostles, black chalk, 23.8 x 18.6 cm (9 1/3 x 7 1/3 in.), Royal Library, Windsor Castle