Raphael

500

Text

Fabio Scaletti

Layout

Break Point sas, Claudio Natale

Pre-press

Gianni Grandi

Editor Stefano Baldassarri

Editorial coordination

Federico Ferrari

Iconographic research

Laura Lopardo

Picture credits

© National Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images: 7, 51, 54, 83, 112, 162, 180. © 2019. Photo Scala, Florence - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Attività Culturali e del Turismo: 8-9, 38, 57, 67, 68, 86, 87, 91, 124, 131, 138, 143, 151, 156, 187, 195, 214, 220-221, 224, 237, 242, 257, 260, 273, 299

© 2019. Photo Scala, Florence: 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26, 34, 35, 42, 58-59, 60, 65, 66, 73, 89, 90, 92, 97, 102, 106, 111, 127, 134-135, 137, 146, 148149, 152-153, 156-157, 158-159, 172, 183, 190-191, 192-193, 194-195, 196197, 199, 200, 204, 206, 208-209, 210, 213, 230-231, 232, 233, 234, 240, 241, 244, 249, 251, 255, 256, 260, 270, 279, 282, 284, 285, 287, 290, 291, 292, 293 © 2019. Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna / Scala, Florence: 41

© 2019. Mario Bonotto / Photo Scala, Florence: 50 © 2019. Foto Austrian Archives / Scala, Florence: 54, 105

© 2019. Photo Scala, Florence / Fondo Edifici di Culto – Ministero dell’Interno: 80, 211

© 2019. Foto Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Scala, Florence: 115, 171, 229, 258

© 2019. The Museum of Fine Arts Budapest / Scala, Florence: 101, 142 © 2019. Christie’s Images, London / Scala, Florence: 250.

© Museu de Arte, Sao Paulo, Brazil / De Agostini Picture Library / G. Dagli Orti / Bridgeman Images: 20

© Hervé Lewandowski / RMN-Réunion des Musées Nationaux / distr. Alinari: 22

© Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany / Tarker / Bridgeman Images: 29, 62-63

© Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany / Artothek / Bridgeman Images: 140

© Heritage Images / Mondadori Portfolio: 30, 32, 84, 132, 258, 259, 294

© Mondadori Portfolio / Akg: 33, 99, 116, 266, 295

© North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, USA / Purchased with funds from Mrs. Nancy Susan Reynolds, the Sarah Graham Kenan Foundation, Julius H. Weitzner, and the State of North Carolina / Bridgeman Images: 33

© The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Jacob Epstein Collection, Maryland, USA / Photography by Mitro Hood: 39

© Norton Simon Art Foundation: 45

© Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA / Bridgeman Images: 46

© Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1916 / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: 49

© Funds from various donors, 1932 / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: 50

© Rogers Fund, 1964 / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: 104

© Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images: 52

© Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Austria / Bridgeman Images: 61

© National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA / Bridgeman Images: 69, 76, 164-165, 217

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK / Bridgeman Images: 75, 210, 289

© Archivi Alinari, Firenze: 96

© Michèle Bellot / RMN-Réunion des Musées Nationaux / distr. Alinari: 98

© Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany / Tarker / Bridgeman Images: 118, 119

© Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany / Bridgeman Images: 141

© Photographic reproduction is from Fototeca della Fondazione Federico Zeri.

Copyright is exhausted: 122

© Prado, Madrid, Spain / Bridgeman Images: 123, 175, 184, 263, 264, 265, 267

© Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana / Malcagni / Mondadori Portfolio: 154-155

© Art Media / Heritage-Images / Mondadori Portfolio: 161

© Musée Condé, Chantilly, France / Bridgeman Images: 168

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Bridgeman Images: 176

© Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth / Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images: 181 Photo © Raffaello Bencini / Bridgeman Images: 198

© Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg, France / Bridgeman Images: 218

© De Agostini Picture Library / A. Dagli Orti / Bridgeman Images: 226

© Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Italy / Bridgeman Images: 269

© Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA / Bridgeman Images: 295 Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019 / Bridgeman Images: 300

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Michèle Bellot: 212

© RMN-Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski: 164

© The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: 250

© National Trust Images / Federico Pérez: 297

© UIG / Alinari Archives: 79, 120-121

© Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK / Bridgeman Images: 245

© Courtesy of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali – Photographic archives of Gallerie Estensi: 265

© Peter Schälchli, Zürich: 227, 274-275, 276

© Album / Prisma / Mondadori Portfolio: 228

© Photo Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin: 30, 222

© National Galleries of Scotland, photography by A. Reeve: 296.

Scripta Maneant is available to settle any rights on reproduction of images of which it was not possible to find the sources.

Volume made by Scripta Maneant editore Via dell’Arcoveggio, 74/2 40129 - Bologna - Italy Tel. +39 051 223535 www.scriptamaneant.it segreteria@scriptamaneant.it

©Scripta Maneant 2020

All rights reserved. Translation, electronic memorisation, reproduction, full or partial adaptation by any means (including microfilm and photocopying) is strictly prohibited in all countries.

ISBN: 978-88-95847-85-6

Editor’s NotE

Raphael’s history is a short-lived but very rich one, that left important works in the history of Western Art.

It is the story of an unequalled master whose figure has lapped that of other leading figures of the Renaissance, and it dealt with prestigious clients. His talent grew with astonishing rapidity, starting with the years of training at the workshop of his father Giovanni Santi: in 1500, only 17 years old, he is already defined “magister”.

A rising star, developing and working between Marche, Umbria and Tuscany, day after day, and becoming the most requested, most well-liked and admired artist.

From Pietro Perugino’s workshop to Pinturicchio’s one (according to Vasari, the entire graphic design of the Piccolomini Library of Siena was due to the young Raphael) and then in Florence, where Raphael absorbs the innovations

IntroductIon

To my brother Aldo

When an artist speaks, art historians must listen and at times, afterwards, keep quiet. Even more so if someone’s discourse concentrates on a compositional philosophy of their own that others are struggling, often in vain, to interpret by dissecting the abstruse meanings. The leading concept in the artistic work of Raphael (1483-1520), the watchword required for crossing the threshold of the Sancta sanctorum of his poetics, was given to us by him in 1514, when he wrote about female attractiveness that “to paint a beautiful one (woman), I need to see more beautiful ones [...] But being honest and good judges, and of beautiful women, I am making use of a certain Idea, that comes to mind. Whether it has any artistic excellence in it, I do not know”. If anything, the historians’ mission is to establish, on the basis of a wide-angle view of events, whether that final declaration of unawareness of his own merits corresponds to a modesty

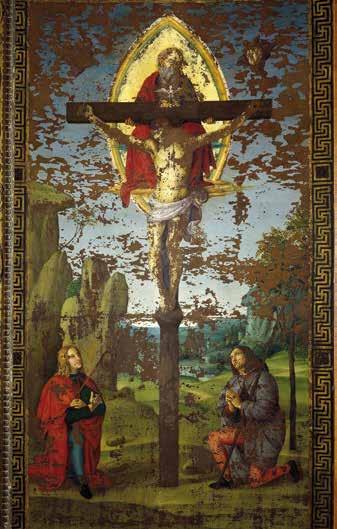

(Opposite page) Raphael, Standard of the Holy Trinity, 1499-1500. Oil on canvas, 167 x 94 cm. Città di Castello, Pinacoteca Comunale.

Front: Holy Trinity with Saints Sebastian and Roch

In a poor state of preservation, the standard was restored in the modern age (1952), in some places revealing the original enamels and glazes.

Early Works

The Standard of the Holy Trinity, 1499-1500.

In the carnet of works unrelated to a contract, the record for the earliest painting by Raphael is held by the Standard of the Holy Trinity, with which many of the monographs dedicated to the supreme artist begin. The painting was mentioned in 1627 and attributed to Raphael, probably made for the church of Santissima Trinità in Città di Castello as a votive offering after the plague broke out in 1499. For a long time, it was used as a processional banner by the confraternity, which seriously damaged it and forced them to take it apart already in 1638, separating the two sides (depicting the Holy Trinity between Saints Roch and Sebastian, on the front, and the Creation of Eve, on the back). The restorations, including the one carried out in the mid-19th century by Count della Porta, could only partially repair the damage.

The opinions of scholars, while varying slightly in regard to the date of execution, have over

The MasTer aT sevenTeen

The Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, 1500-1501.

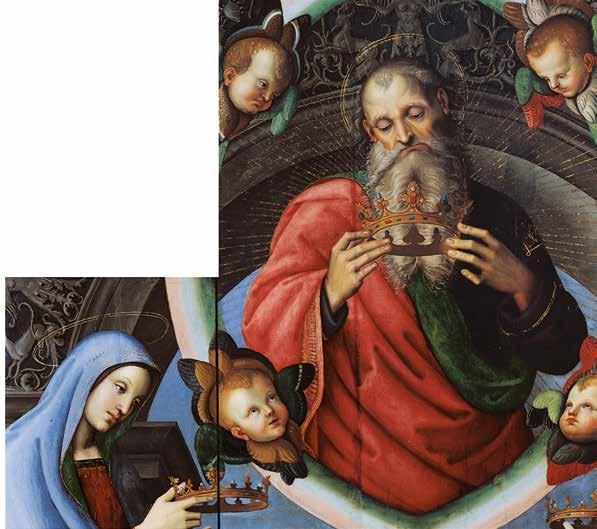

The first documented work by Raphael (then seventeen and already called “master” in the contract) is also the only one that passed down to us heavily mutilated, because, having been commissioned by Andrea Baronci in December 1500 for the church of Sant’Agostino in Città di Castello and delivered in September of the following year, it emerged irremediably damaged by an earthquake in 1789. The surviving pieces, immediately sold to Pope Pius VI, were requisitioned by Napoleon, and then returned to Rome to later arrive in Naples, where two parts are still preserved at the

Raphael, the Virgin Mary with the Crown, fragment of the Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, 1500-1501. Oil on panel, 51 x 41 cm. Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. 50.

The X-rays carried out on this fragment, and on the other kept in the same location, led scholars to establish Raphael as the artist.

Capodimonte Museum, the Eternal Father with Cherubs and the Virgin Mary. The other fragments went missing, some being identified only at the beginning of the 20th century, the Head of an Angel at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia, found in 1822 on the Florentine market, and, in 1982, the Angel Holding a Phylactery in the Louvre.

A valid aid to scholars for reconstructing the original facies of the Baronci Altarpiece was provided, in addition to a partial 18th-century copy (Città di Castello, Pinacoteca Comunale), from Raphael’s drawings, one at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and another, perhaps the most useful for completing the puzzle, at the museum in Lille. It was thought that the predella of the altarpiece could also be recognized, with the stories of the saint narrated in three compartments, namely Nicholas of Tolentino

(Page 19)

Raphael, Eternal Father with cherubs, fragment of the Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, 1500-1501.

Oil on panel, 112 x 75 cm. Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. 50. The original work, only some parts of which have come down to us, is also called the Pala (Altarpiece) Baronci, from the name of the client, a merchant who was also prior of Città di Castello.

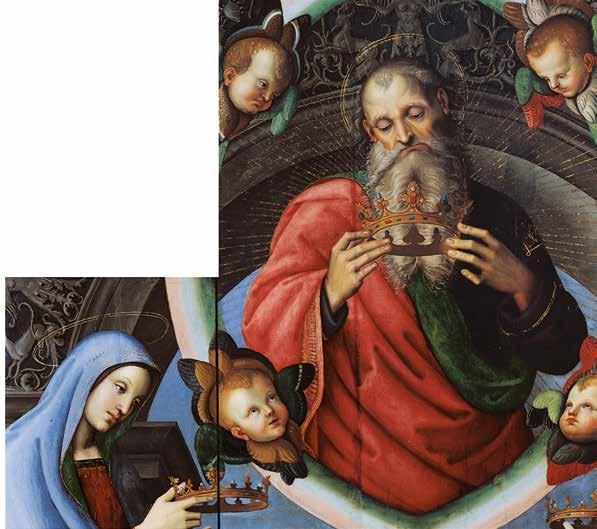

Raphael, Angel with Cartouche, fragment of the Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, 1500-1501.

Oil on panel, 57 x 36 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. RF 1981-55. Here, in addition to influences from Perugino are accents from Signorelli.

Raphael, Resurrection of Christ, 1501 ca. Oil on panel, 52 x 44 cm. São Paulo in Brazil Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), inv. 17.1958. The work’s small dimensions could suggest a predella compartment.

(Opposite page)

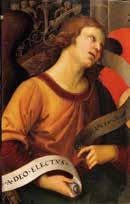

Raphael, Angel, fragment of the Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, 1500-1501. Oil on panel transferred to canvas, 31 x 27 cm. Brescia, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, inv. 149.

As with the other fragments, the influence of Perugino, Raphael’s first teacher, is clear.

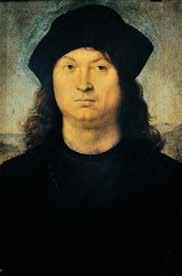

Raphael (attributed), Portrait of a Man, 1502 ca. Oil on panel, 45 x 31 cm.

Rome, Galleria Borghese, inv. 397. In the past, coming from the Aldobrandini collections in Rome, it was ascribed to Perugino or considered a self-portrait. The frontal layout and the Nordic component are recurring elements in Raphael’s early portraiture.

Raphael?, Portrait of Perugino, 1504. Oil and tempera on panel, 51 x 37 cm. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv. 1890, no. 1482. Recorded in the Medici collections of 1704, it almost certainly depicts Perugino, on evaluating those of his features passed down from other portraits or self-portraits.

the 19th and 20th centuries, also in the wake of an alleged resemblance between the portrayed subject and the Guidobaldo da Montefeltro (Duke of Urbino) today in the Uffizi, a physiognomic similarity that many have not accepted (recently the name of Andrea Acquaviva, Duke of Atri was proposed). The 1982 restoration did not reveal an underlying drawing.

Listed as a work by Raphael portraying Perugino (not in wording affixed to the artefact but in an entry in the Borghese archive of 1765) is also the Portrait of a Man (still in the Galleria Borghese in Rome). Its authentication has been maintained even after the restoration of 1911 which removed some repainting (a fur coat and shirt with lace edging), although many more recent scholars have expressed doubts, which have also involved the identity of the portrayed subject, for which the names of Pinturicchio and Francesco Maria della Rovere have been bandied about.

Pietro Vannucci, Raphael’s teacher, should instead be the character at the centre of the Portrait of Perugino in the Uffizi, after other identities, such as Martin Luther and Verrocchio, had been proposed. Some have suggested such authors as Holbein, Lorenzo di Credi and Perugino himself, until in 1934 the name of Sanzio was brought up, not currently approved by all. The recent restoration has brought back its original brilliance and made it possible to perceive a reddish-coloured brush pattern used in other original works and specified by the reflectography as a refined chiaroscuro pattern.

perspective lines reminiscent of the rules dictated by Piero della Francesca, the temple with sixteen sides – implying a knowledge of Bramante’s temple of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome and which, as revealed by the reflectography, was traced free hand after the figures were executed - and the semi-circular group of marriage participants. One of the “suitors” on the right, breaks the dry rod, not by chance, against the flowering rod of the groom Joseph, seeing himself discarded as Mary’s choice.

Vasari, already in 1568, had dwelt on this unprecedented way of understanding space, and wrote that “in this work a temple is drawn in perspective with great love, which is admirable on seeing the difficulties he was up against in this exercise”.

The altarpiece’s geometric structure has an equivalent in its numerical symbolism: for example, the twelve figures in the foreground refer to the twelve signs of the zodiac and the twelve apostles (the thirteenth figure, the priest, is equivalent to Christ, who is together with the disciples).

The panel came to Brera at the behest of the viceroy Beauharnais, after it had been removed, in 1798, from the altar for which it had been painted (in the chapel of San Giuseppe in the church of San Francesco in Città di Castello) by order of Filippo Albizzini to please the general of the cisalpine army, Giuseppe Lechi. In 1803, the latter sold it to the Milanese Jacopo Sannazzaro, who the following year left it at the Ospedale Maggiore.

(Opposite page)

Raphael, Marriage of the Virgin, 1504. Oil on panel, 170 x 118 cm. Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera, inv. 472.

Signed on the frieze of the portico “RAPHAEL URBINAS” and dated on the pendentives of the arch “MDIIII”. The modern diagnostic surveys, used again in the 2008 restoration, revealed a drawing with some “pentimenti” under the painted surface, in other words, variations to the work in progress. Preparatory studies for female heads are preserved at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

(Detail on pages 8-9)

The FlorenTine ATmosphere

Two rounded Madonnas.

In the autumn of 1504 Raphael set foot, probably not for the first time, in Florence. He stayed there for about four years and carrying a letter of introduction to the standard bearer Pier Soderini, written by Giovanna Feltria della Rovere, he worked for aristocrats and members of the wealthy bourgeoisie, painting sacred paintings, particularly Madonnas, and portraits. Francesco Maria della Rovere, son of the aforementioned noblewoman, is probably the subject of the Portrait of Young Man with an Apple (Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi), portrayed at age fourteen at the time of his appointment as heir to the Duchy of Urbino, then ruled by his uncle Guidubaldo (for most critics, portrayed by Sanzio in another picture preserved in the Uffizi, who incidentally sports a similar garment with a gold weave). The golden apple symbolizes the position he is destined to assume and for some, would refer to The Three Graces, now in Chantilly, painted on commission from the Dukes of Urbino.

Saint Lawrence, Saint Jerome, Saint Maurus and Saint Placidus”), comments that it was “for what in a fresco was then held as very beautiful”, a judgment that reflects what modern scholars perceived in it, a co-presence of Peruginesque sonorities, especially in the coy angels, of Fra Bartolomeo in the voluminous nature of the saints’ robes (on the contrary, some have assumed that the friar directly intervened), and Leonardesque suggestions in the chiaroscuro figure of Christ. The influences of Da Vinci are confirmed in the sketches on a sheet with a study of hands and heads for the fresco of San Severo preserved in the Ashmolean in Oxford (other preparatory drawings for the painting are in the museums in Chantilly and Lille).

The central body is whole but the “accessory” parts are incomplete (we have only one compartment, the one with Saint John the Baptist Preaching) and the Madonna and Child Enthroned between Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas of Bari, known as the Ansidei Altarpiece after the name of the family who ordered it for the chapel of San Nicola in Bari (patron saint of merchants) in the church of San Fiorenzo dei Serviti in Perugia, where it was until 1764, when it was bought by Lord Spencer, from whom it passed to the fourth Duke of Marlborough and, in 1885, to today’s location.

On the exact chronology of this Sacra Conversazione, despite the date on the edge of the robe, under the elbow of the Madonna, scholars

(Opposite page)

Raphael, Madonna and Child

Enthroned between Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas of Bari (Ansidei Altarpiece), 1505.

Oil on panel, 216.8 x 147.6 cm. London, National Gallery, inv. 1171. Dated on the hem of the Virgin’s mantle: “MDV”. Often emphasized in this altarpiece is the virtuous execution, including that of the throne, comparable an authentic piece of high-quality carpentry.

His Life in Brief

“An Italian would rather sell you his original wife, than an original by Raphael.” (Montesquieu 1728)

Training and early work in Urbino and Perugia

1483

On April 6 (according to some the date should be brought forward to March 28) Raphael was born in Urbino, son of Magia Ciarla and Giovanni Santi, painter and scholar working at the Montefeltro court, author of a Cronaca rimata (Rhyming Chronicle) in which he gives an interesting overview of the cultural environment and artists of the time: including Masaccio, Gentile da Fabriano, Beato Angelico, Pisanello, Piero della Francesca, but also Donatello and Flemish masters like Van Eyck. Those who would mostly influence his talented son are to be added, such as Perugino, Pinturicchio, Signorelli, Pollaiolo, Mantegna, and of course Leonardo and Bramante. The artist Latinized his surname to “Santius”, “Sanzio”.

1491

Death of the mother, perhaps in childbirth. According to tradition (Vasari) the period of apprenticeship had already begun in the workshop of Perugino in Florence and Perugia.

1494

Death of his father, who bequeathed him the workshop, run with Evangelista da Pian di Meleto, main collaborator to his deceased parent. The care of the 11-year-old orphan was probably entrusted to the paternal uncle, the archpriest Bartolomeo Santi.

1500

At only seventeen he was called magister in the contract for the commission of the altarpiece with the Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, completed the following year with Evangelista, of which today there remain some fragments spread around different museums.

1501-1502

The abbess of the Poor Clares of Monteluce in Perugia commissioned him for a Coronation of the Virgin, never executed.

The first Madonnas and portraits date back to this period.

1503

This date appeared on the altar that hosted the so-called Mond Crucifixion (today in the National Gallery in London) in San Domenico in Città di Castello. He went to Siena with Pinturicchio and designed the cartoons for the frescoes in the Piccolomini Library in the Cathedral.

1504

At the beginning of the year he lived in Perugia. He painted Marriage of the Virgin (Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) for the church of San Francesco in Città di Castello.

He moved to Florence, preceded by a letter (moreover of dubious authorship) by Giovanna da Montefeltro, who recommended him to Pier Soderini, gonfalonier of the Florentine Republic.

The Florentine interlude

1504-1507

He was making portraits, including the two of the Doni spouses (Florence, Pitti) and Madonnas, including the Madonna del baldacchino (Florence, Pitti). But several works were destined for Perugia, such as the Ansidei Altarpiece (London, National Gallery) and the Transport of Christ to the Sepulchre (Rome, Galleria Borghese). The date 1505 is affixed to the fresco Holy Trinity and Saints in San Severo in Perugia. According to some sources, in roughly 1507, when he would have been in Urbino, he paints one an Agony in the Garden, lost, for Elisabetta Gonzaga, who also, according to a poetic composition by Baldassar Castiglione, was portrayed by Raphael in a painting he owned.

Raphael, Departure of Enea Silvio Piccolomini for the Council of Basel, 15021503. Black pencil, pen, brown watercolours, white lead on squared paper, arched, 705 x 415 mm. An inscription above, perhaps in his hand. Florence, Uffizi, Department of Drawings and Prints, inv. 520E. For the frescoes in the Piccolomini Library in the Duomo of Siena commissioned to Pinturicchio, the young Raphael composed a series of drawings (preserved in Oxford and the Louvre), a cartoon (New York, already in Perugia, Baldeschi collection) and this sheet, sketched in pencil, painted over with pen, watercolour and touched-up with white lead, a technique he often used.