York London

The genre of East Asian painting known as “bird-andflower pictures” originated in China during the Song dy nasty and spread to Japan in the fourteenth to sixteenth century. Although birds and flowers are indeed the most common subjects, the genre encompasses all kinds of nature studies, including animals, insects, and marine life. Sometimes depictions of flora and fauna have symbolic meanings: for example, cranes are auspicious symbols of longevity, as are pine trees and turtles; bamboo symbolizes resilience. Floral motifs are strongly associated with the changing seasons.

The Kano school, official painters to the shogun, often used nature motifs— painted either in monochrome ink or in brilliant color—blown up to a large scale on folding screens or sliding door panels as interior decoration for temples and palaces. Nature studies also appeared in the form of book-shaped albums of small paintings, with individual works pasted onto the pages; and these painted albums provided inspiration for early printed books of the same themes. Chi nese printed painting manuals were also influential.

In single-sheet prints, there are scattered examples of bird-and-flower prints throughout the history of ukiyo-e, and some especially lovely examples were made in the early days of full-color printing by artists such as Harunobu and Koryūsai. But as in the case of landscape prints, the true breakthrough came only in the 1830s, with the work of Hokusai and Hiroshige. Nature, like land scapes and historical events, became a major genre of ukiyo-e printmaking at this time, comparable in popularity to the long-established genres of actors and women.

Often the bird-and-flower prints are embellished with poetry of various kinds, recalling the origins of the genre in elegant Chinese painting.

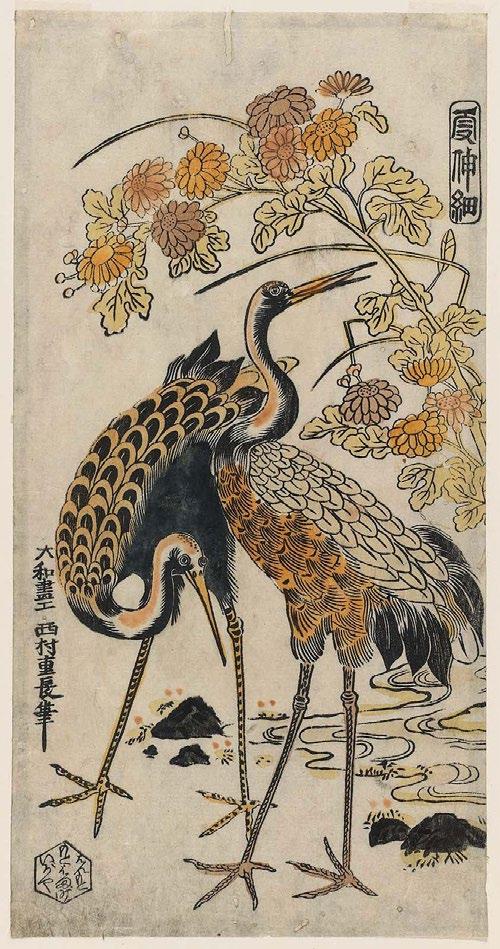

Publisher: Igaya Kan'emon (Bunkidō)

Cranes and Chrysanthemums, from a bird-and-flower series with the title Kashinsai (?), c. 1730 Woodblock print (urushi-e); ink on paper, with handapplied color and nikawa Hosoban; 12¼ × 6¼ in. (31.1 × 15.9 cm)

Bird-and-flower prints are not common in early ukiyo-e, but there are a few beautiful examples such as the prints in this series, whose title remains undeciphered. Two cranes, symbols of long life and good fortune, pose in front of a chrysanthemum bush with multicolored flowers. Hand-colored prints of this type are sometimes called “lacquer prints” (urushi-e) because the hand-applied colors include black ink mixed with glue (nikawa) so that it will look shiny and lacquer-like when it dries.

Publisher: Nishimuraya

Yohachi (Eijudō)

Eagle on a Pine Branch in the Rain, 1770s

Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Vertical chūban; 10⅛ × 7⅜ in. (25.8 × 18.7 cm)

Unlike most ukiyo-e artists, Koryūsai was born into the samurai class and so enjoyed an elite education whose influence can sometimes be seen in his work. Birds of prey, symbolizing the warlike character aspired to by the samurai, were favored subject matter for the painted door panels, folding screens, and hanging scrolls that decorated upper-class homes. Koryūsai’s print of the mighty bird unfazed by bad weather showcases his drawing skills and brings the statusful subject within financial reach of the average townsperson.

Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudō)

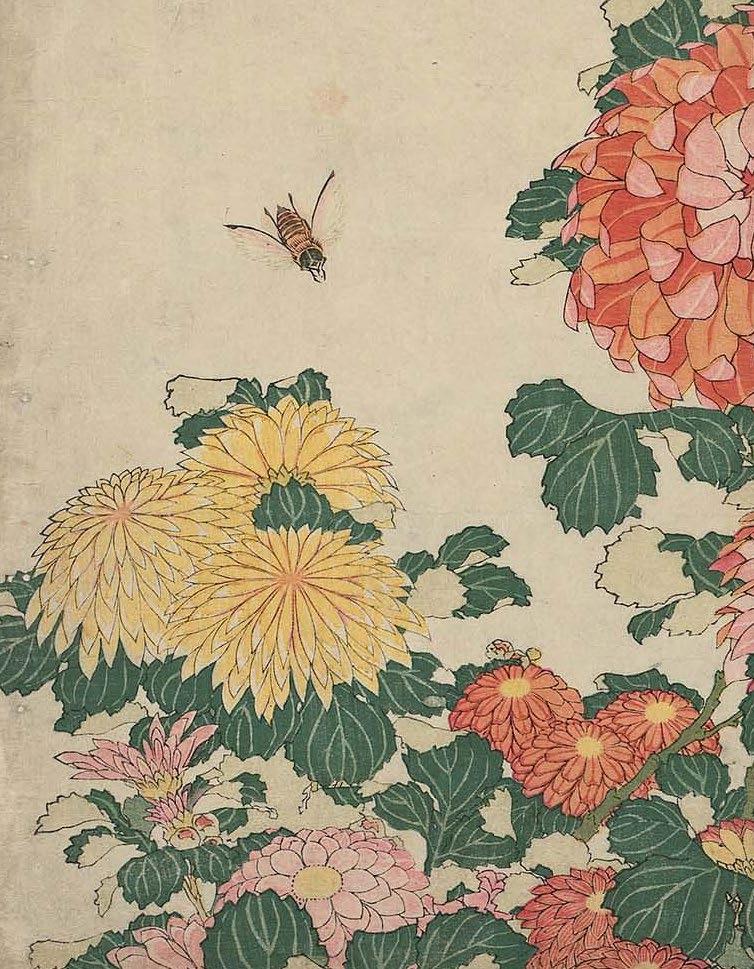

Chrysanthemums and Horsefly, from an untitled series known as Large Flowers, c. 1833–34 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Horizontal ōban; 10 × 14⅝ in. (25.3 × 37 cm)

Hokusai’s untitled series known as Large Flowers did for bird-and-flower prints what his Fuji series had done for landscape just a few years earlier: take a minor area of subject matter in ukiyo-e and turn it into a major one through the brilliance of his designs. The flowers are shown in closeup, at eye level, so that they come to life as if the viewer were on the ground beside them. Many of the designs in the series include birds or insects that add to the impression of life and motion.

Bellflower and Dragonfly, from an untitled series known as Large Flowers, c. 1833–34 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Horizontal ōban; 10½ × 15½ in. (26.6 × 39.4 cm)

Because they bloom at the end of the summer, bellflowers were traditionally regarded as one of the Seven Plants of Autumn, celebrated in Japanese poetry. Their usual color is a dark blue-purple, but as Hokusai shows, other varieties also exist. The addition of the dragonfly suggests that Hokusai may have been influenced by an image of a dragonfly and bellflowers in a poetry album by Utamaro, Selected Insects (Mushi erabi), published in 1788 when Hokusai was still an aspiring young artist of the Katsukawa school.

Publisher: Nishimuraya

Yohachi (Eijudō)

Peonies and Canary (Shakuyaku, kanaari), from an untitled series known as Small Flowers, c. 1834 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Vertical chūban; 10¼ × 7½ in. (26 × 19.2 cm)

According to a Chinese saying, tree peonies were at their finest in the city of Loyang and herbaceous peonies (the type shown here) in Yangzhou. The brilliant yellow canary is an exotic songbird that originated in the islands of the Atlantic and was imported into Japan by Dutch traders. The Chinese couplet inscribed on the print is by the Northern Song dynasty poet Wang Shiming (1112–1171): “The Yangzhou peony with its thousand leaves,/ supreme among the fragrances of spring.”

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudō)

Bullfinch and Weeping Cherry (Uso, shidarezakura), from an untitled series known as Small Flowers, c. 1834

Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Vertical chūban; 10 × 7⅜ in. (25.5 × 18.7 cm)

A sparrow-sized bird with a distinctive red throat and a whistling call, the bullfinch perches on a dangling branch with both buds and blossoms. The haikai poem is by Senraian Setsuman, the poetry name of the shamisen master Sugano Joyū II (1784–1841): “Just a single bird/ emerging in morning damp/ from cherry blossoms.” In addition to his music and poetry, he was also a painter and a tea master, and he may have been a personal acquaintance of Hokusai.