Our Voices II: the de-colonial project

By Rebecca Kiddle, luugigyoo patrick stewart, and Kevin O’Brien

Table of Contents

Foreword: Frontier Conflict – Fiona Foley

Mayem [welcome] : Introduction

The Ethics of writing and producing a book on De-colonisation – Rebecca Kiddle, luugigyoo patrick stewart, and Kevin O’Brien

kopat [everybody together] (section 1): People and Community

Song **: E ko – Earthfeather (aka Josephine Clarke)

Chapter 1.1: Sacred Superwoman – Linda Lavallee

Chapter 1.2: Decolonizing one child at a time – luugigyoo patrick stewart

Chapter 1.3: Island Child and Heroic Work for Homeless Families – Diane Menzies

Chapter 1.4: Ngā Mahi ā Te Whare Pora: The unravelling of ‘colonial’ Christchurch through the creative practices of wāhine – Keri Whaitiri

Chapter 1.5: The Contemporary Indigenous Village: Decolonization Through Reoccupation and Design – Daniel J. Glenn

Chapter 1.6: Seeking Cultural Relevancy in Dine Communities – Richard Begay

meta [house] dewer [to build] (Section 2): Architecture and Building

Poem **: Not Dead Yet – Timmah Ball

Chapter 2.1: Blak Box – Kevin O’Brien

Chapter 2.2: The Whare Māori and Digital Ontological Praxis – Reuben Friend

Chapter 2.3: Rangi’s Turn - Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta

Chapter 2.4: Niimii’idiwigamig Anishinaabe Roundhouse – Eladia Smoke

Chapter 2.5: Tipi Tectonics: Building as a Medicine - Krystel Clark

Chapter 2.6: The Indigenous Peoples Space: Architecture as Narrative – Eladia Smoke, David Fortin and Wanda Dalla Costa

meriba ged [our land] (Section 3): Country and City

Poem **: K’alii’aks – luugigyoo patrick stewart

Chapter 3.1: Rebuilding Renewal – Jason De Santolo

Chapter 3.2: Designing with Country - Dillon Kombumerri and Daniele Hromek

Chapter 3.3: Contested Ground – Weaving stories of spatial resilience, resistance, relationality and reclamation – Daniele Hromek

Chapter 3.4: Covered by Concrete – Uncovering latent Aboriginal narratives concealed in urban contexts – Michael Hromek, Sian Hromek and Daniele Hromek

Chapter 3.5: Urban Manaakitanga as Counter-Colonial Mahi – Amanda Yates

dirsir [to prepare, fix, make] (section 4): Principles and Action

Poem **: Lineage – Kristi Leora Gansworth

Chapter 4.1: An Architecture of Twenty-Five Projects – Michael Mossman

Chapter 4.2: Navigating the gaps in Architectural education – Fleur Palmer

Chapter 4.3: Designing Māori Futures - Ngā Aho, Māori Design Professionals – Desna WhaangaSchollum & Ngā Aho

Chapter 4.4: Developing Indigenous design principles – lessons from Aotearoa – Edited by Jade Kake and Jacqueline Paul

Chapter 4.5: Guiding Decolonial Trajectories in Design: An Indigenous Position – Brian Martin and Jefa Greenaway

Chapter 4.6: #dickdesigner – How not to be one: Colonisation, and therefore decolonisation, is in the detail - Rebecca Kiddle

mop pe dike [talk at end] : Conclusion – Rebecca Kiddle, luugigyoo patrick stewart, and Kevin O’Brien

Foreword: Frontier Conflict

Fiona Foley

Badtjala

In Bruce Pascoe’s most recent publication titled, Salt , he states, “Any nation’s artists and thinkers set the tone and breadth of national conversation.” That national conversation at some point must take into account the invasion and subsequent frontier wars of Australia and reparations to the sovereign Aboriginal nations of this continent.

As a five-year old child, I remember looking across to Fraser Island and experiencing a deep sense of loss. It was a loss for my country, for my culture and for my old people. From an early age I wanted to know more because I have an intellect and am curious. That is not a crime. I became a racialised person – not from my family, but by other’s, when I entered the school gates at Urangan, Hervey Bay. My parents faced much racism in the 1970s and at one point were forced to leave Hervey Bay and move to Mt. Isa to escape the pressures of race hatred because of their mixed marriage. By then I was in third grade.

Racism in this country is a topic we like to avoid discussing but it manifests itself everywhere, including in architectural process and practice, the focus of this book. It is a societal burden I’ve learned to carry. That gaze wrapped up in judgment from a white society and white individuals. For me it manifests itself in everyday educational environments, including my present-day status as an academic at Griffith University, with “Dr” in front of my name.

As an adult, I reflect on the fact that many in Australia carry deep psychological scars from what Judy Atkinson terms intergenerational trauma. Aboriginal people were not allowed to bury our dead after massacres had taken place. I believe this country carries deep wounds from the trauma of these frontier wars. We carry it inside our souls whether we are conscious of it or not. This brutality, in turn, has also affected the perpetrators and their descendants.

I did not know I was destined to be an artist in life but that has sustained me for the past 35 years. While studying in the sculpture department at Sydney College of the Arts I created a sculpture in 1986 Annihilation of the Blacks that speaks to this trauma. I was told about a massacre on my country along the Susan River by my late mother, Shirley Foley. Indeed, many such oral histories are carried, in the living memory, of Aboriginal people. That image stayed with me, the image of the Badtjala

people being maimed, killed or fleeing on foot. It was a powerful history to carry and to make of it – something. A kind of decolonial act.

Art and politics have had an uneasy relationship in this country. Many years later after the initial purchase of my sculpture, Annihilation of the Blacks courted controversy from the conservative, John Howard government. The sculpture, and what it symbolised played a role in the history wars unfolding nationally contributing to the non-renewal of Dawn Casey’s contract as the Director of the National Museum of Australia, as a case in point. Dawn Casey, an Indigenous Australian, oversaw the “democratisation of museums” and fore fronted Indigenous challenges, working under a regime that was antagonistic to Indigenous worldviews.

Fast forward to another Canberra institution, the National Gallery of Australia. People may be familiar with my work titled, Dispersed . This work was created after reading a number of publications by historians such as Rosalind Kidd, Jonathan Richards, Raymond Evans and Tony Roberts. Reading about what really took place in Queensland has been a lifetime passion of mine to find out the truth, attitudes held by the colonial man and woman, a guerrilla war with strategic and repeated attacks on the invader. We were not passive in the take-over of our country despite the fact that some have said to me on occasion, “Australia had been settled peacefully.” Let’s remember that every inch of Queensland soil has been fought over and bloodied.

Finding the true history of Queensland was a slow process of reading and piecing together an epic jigsaw puzzle one piece at a time. No one taught me in a classroom setting about the history of Queensland and its race politics. Only through the simple act of reading books I taught myself about the true counter narrative. In 1984, the first book I bought on this subject was by C.D. Rowley, titled The Destruction of Aboriginal Society Then it was a slow grind reading book after book after book, unfolding over decades. Australia has an uneasy relationship with our history as we keep running into a stock standard conservative, revisionist pathology.

My life has been about the fight for justice for Aboriginal people and telling the true history of Australia.

My platform has been through the visual arts. Visual arts, architecture, landscape design ... it all has power to provoke and inch by inch move us towards decolonisation in sometimes subtle and other times overt ways. I will end here with a quote by the writer Toni Morrison – she says, “facts CAN exist without human intelligence – but truth cannot.”

A collaborative team has made a valuable contribution to the research not currently known before in Queensland. Taking shape through the discipline of archaeology and Indigenous knowledge from Aboriginal descendants of frontier conflict they have been able to join forces to bring this information to the general public. This research was funded through an Australian Research Council Discovery Project grant (DP160100307, The Archaeology of the Queensland Native Mounted Police) from 2016–2020. It was a joint project conducted by researchers from Flinders University, the University of Southern Queensland, the University of Notre Dame Australia, the University of New England and James Cook University.

Mayem [welcome]: Introduction

The

Ethics of writing and producing a book on De-colonisation

This book picks up where Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture left off. It continues in the same vein of Indigenous authorship and collaboration to maintain space for our voices within the built environment. We must speak into the contexts that directly affect ourselves, our communities and the cultural impacts the modern world has brought us. This collaboration includes editors and authors of Indigenous heritage from Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), Turtle Island Canada and the United States. The diversity of contributions reflects an acute awareness of the effects of colonisation and how we might move beyond the continued trauma and violence. It includes works from the perspectives of artists, academics, designers, architects, planners, urban designers and policy strategists.

Our Voices: The DE-colonial Project showcases works that seek to confront the limitations of the colonial built environment. The land, towns and cities on which we live have always been Indigenous places yet, for the most part our Indigenous value sets and identities have been disregarded or appropriated. Indigenous Peoples continue to be gentrified out of the places to which they belong and both neo-conservative and neo‐liberal systems work to continuously subjugate Indigenous involvement in decision‐making processes in differing, but equally effective ways. However, we are not, and have never been cultural dopes. Rather, we have, and continue to, subvert the colonial value sets that overlay our places in important ways.

Between July 4-6 of 2019, the Our Voices: The DEcolonial Project open conference brought together many of the contributors to the University of Sydney. For three days, presentations and discussions considered not just the colonising effects of those wo/man made things that surround us (i.e. architecture and the city) but also the colonising effects on the Indigenous body. From identity, to fashion and to homelessness, it was made clear that our skin (i.e. colour), what we put on (i.e. clothes) and how we might be in public space (i.e. act) is invariably viewed through a colonial filter as an “Indigenous problem.” It reminded us all that the presence of Indigenous Peoples in our cities and Countries begins (and arguably ends) with the human experience. The resulting framework for this book was deliberately broadened to enable a variety of interpretations and contributions that have come together as a demonstration

of the depth and breadth of thought around de-colonising practices and projects.

Another word on Indigenous

The use of the word Indigenous, with a capital “I” extends its application in Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture as an ongoing editorial position to move beyond the colonial origins of the word. This move continues the assertion from the first book that the inherent importance of the notion of Indigenous (and Indigeneity) as a shared identity with a related set of knowledges and experiences. It does, however, remain a genuine paradox to recondition a collective word that is acceptable and respectful to the various origins of the contributors. The reframing and reclaiming of this and other words that might describe our greater collective is consistent with cultural, political and philosophical change.

Other words such as native, aborigine, aboriginal and indigenous are used throughout the world to identify Indigenous Peoples on general terms as “other.” Indeed, these words are present even in this book as a sign of the underpinning political sentiment and ideology surrounding the contributor’s unique experience and position and the fields in which they operate. However, where in Aotearoa New Zealand “Native” has been rejected in favour of “Māori,” and in Turtle Island Canada, Indigenous is becoming the norm and Australia “Aborigine/Aboriginal” has become accepted, there is no substitute for the more precise tribal identity that is delivered through nation, language, totemic or clan names. Identity is complex and many things define and, most importantly, unite us.

De-colonisation/de-colonising/de-colonise

The focus of this book is bound to the Indigenous origins of the contributors and therefore specifically addresses those moves to counter the destructive legacies of European colonisation in Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), Turtle Island Canada and the United States today. These counter moves are the de-colonial projects presented in this book. However, it must also be understood that these de-colonial projects are part of much larger intellectual, theoretical and political fields that reach deep into global history and stretch well beyond the remit of this book.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous People published by Zed Books Ltd, London and New York, and the University of Otago Press, Dunedin, in 1999 is considered a seminal text critiquing euro-centric concepts of research to articulate a new research agenda from an Indigenous position. It is frequently referenced and highly influential in this part of the world. Presented in two parts, the first part (amongst other points) identifies research classification as a weapon used to subjugate the minds of Indigenous people. In the second part, the suspicion of research in Māori communities was argued as an active form of colonisation that sought to remove agency from Indigenous people. These two points are in no way a summary of a much more comprehensive text, rather, they have struck thematic chords in this book where “freedom of mind” leads to cultural engagement, and “agency” leads to self-determination.

The Ethics of Production

In this book we have continued the ambition of the Indigenous voice to guide both content and process set out in Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture. Beginning with the shared Indigenous culture of our editorial group of Rebecca Kiddle (Ngāti Porou and Ngā Puhi, urbanist and academic), luugigyoo patrick stewart (Nisga’a, architect and academic) and Kevin O’Brien (Kaurereg and Meriam, architect and academic), it was extended to include sub-editors Rau Hoskins (Ngāti Hau and Ngā Puhi, architect, and academic), David Fortin (Métis, architect, and academic) and Michael Mossman (kuku yalanji, architect and academic). As a group, it was possible to maintain a forum where process and intent could be discussed around the questions arising from such a general term as “Indigenous.” Thankfully, the first book tested and set our original framework for ensuring a safe cultural space for all contributors. This book not only extends the intention to make it even more accessible to all those with something to say, but also to feel safe in saying it in their own way.

Each contribution has been peer reviewed in an open manner by at least two members of the broader editorial group; in many cases, especially the academic contributions, also by many others prior to being included here. It is worth reminding that in support of Indigeneity, we wanted to privilege Indigenous knowledges and research/writing methodologies as being central to our process. Authors were encouraged to seek peer review from those in their communities whom they respected. This review process was set out in Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture and predicated on the work of the National Collaborating Centre on Aboriginal Health (NCCAH) in Canada who developed an Indigenous peer review framework for a journal publication they had developed. We again thank them for this seminal work.

The NCCAH set out a number of goals that have been

duplicated and taken on board for this publication given their relevance. These assert that this publication will:

• Create a place of respect and safety where Indigenous writing and wisdom is valued and acknowledged;

• Provide a new model of publication that creates access for Indigenous scholars;

• Provide a place of dialogue and sharing;

• Promote Indigenous Peoples academic research and writing;

• Promote and mentor Indigenous talent;

• Reclaim our voice;

• Showcase best Indigenous practice; and,

• Encourage cultural competence and congruence through research and making connections to administration, policy and practice (NCCAH:2007).

This has meant there are contributions that range from song and poetry, to opinion pieces in addition to more architectural profession and academic pieces that in total represent a broad spectrum of thought and position. Across this spectrum, one concept unites us all, that of the need for the Indigenous voice in guiding our changing environments.

The arrangement and format

This book is hosted in Australia and for that reason, the first words emanate from Fiona Foley, a Badtjala woman and internationally acclaimed artist. Fiona Foley has kindly contributed an opening foreword outlining her experiences as presented in her keynote address at the Our Voices: The DE-colonial Project in July 4-6, 2019. This is followed by this introduction and concluded with the last words led by co-editor, Kevin O’Brien of Kaurereg and Meriam descent. There are four sections, each cotitled in Meriam (in honour of Kevin O’Brien’s maternal line) and English languages.

kopat [everybody together] (section 1): People and Community reminds us that the de-colonial project starts with our lived experience and originates in our bodies. The section begins with the lyrics of a song from Earth feather (aka Josephine Clarke) describing how language, when plucked out from a community, has a devastating effect on culture and the identity of a people. An invitation is extended to simply read the lyrics aloud and listen to the sounds. These sounds, and the associated rhythms intimate how language, and therefore people, belong to the land. This work sets the theme for this section and is followed by Linda Lavallee’s ongoing work in fashion where the positive expression of cultural identity in public spaces can attract unwanted negative behaviours from the non-indigenous community. luugigyoo patrick stewart and Diane Menzies writings independently discuss the need to support the de-colonising process with our children and through our communities. Keri

Whaitiri, Daniel J. Glenn, and Richard Begay continue the discussion and extend the notion of community into built conditions of urban recovery, contemporary village and cultural relevancy respectively.

meta [house] dewer [to build] (Section 2): Architecture and Building begins with a searing poem by Timmah Ball that laments the injustice of a land title system supporting the beguile of its planning and architectural representatives. Blak Box, a travelling pavilion for the telling of stories by Kevin O”Brien, suggests that identity begins in thought, transpires as sounds and ends in an aesthetic. Reuben Friend’s writing takes us from the physical to the virtual and introduces questions around how cultural knowledge might be stored, accessed and most importantly enabled through guardianship. Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta’s story outlines a way into space and placemaking as a matter of agency. Eladia Smoke and Krystel Clark separately discuss how agency informs the building through cultural ideation and healing respectively. This section is brought together through Eladia Smoke, David Fortin and Wanda Dalla Costa’s cowritten piece addressing the challenges and ambitions of a significant cultural building located at the contested intersection of politics, culture, history and identity.

meriba ged [our land] (Section 3): Country and City considers a larger scale of context in which the previous two sections sit. Jason De Santolo introduces the idea of Country as a living entity that people belong to and care for in a cycle of renewal. A way into designing with Country is further explored by Dillon Kombumerri and Daniele Hromek’s co-written piece. This is followed by Daniele Hromek’s stand-alone piece addressing the nature of contested ground in the city; and also a further piece co-written with siblings Michael Hromek and Sian Hromek that demonstrates the potency of uncovering latent narratives in urban contexts. Amanda Yates ends this section examining de-colonisation as a social-cultural-political process. One that proposes that Indigenous urbanism grounded on agricultural activism is a powerful urban decolonising practice.

dirsir [to prepare, fix, make] (section 4): Principles and Action invites us to think and act. Kristi Leora Gansworth’s poem beautifully expresses the spirit as a source of knowledge informed by a principled view of the planet, introducing an inclusive start to the section. Michael Mossman’s explanation of a design studio of 25 projects worked in close collaboration with community demonstrates an inclusive approach to teaching non-indigenous students about engagement and culture specificity. Fleur Palmer dissects the prevalent Eurocentric system of architectural education and calls for a rethinking that addresses the interconnected-ness of all things. Desna Whaanga-Schollum and Ngā Aho’s paper continues this view to describe a large network of design professionals who meet, discuss and act on issues enabling leadership in their creative disciplines and working contexts. Jade Kake’s paper, and Brian Martin

and Jefa Greenaway’s co-written paper, both contribute to the complex and dynamic discussion around the specificity and application of Indigenous design principles and guidelines in practice and in institutions respectively. The final paper by Rebecca Kiddle summarily shares some friendly advice around how we might engage with the principles and actions previously outlined so as not to undermine nor dilute Indigenous leadership and knowledge.

Our Voices: The DE-colonial Project draws together a broad spectrum of voices to address issues confronting Indigenous peoples in Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Turtle Island Canada and the United States of America. Although comprehensive in its global reach, it is by no means a claim to a definitive position on the de-colonial project. Rather, this is a space for the active concerns and endeavours of multiple indigenous voices at this point in time.

References

Smith, L.T. (1999) decolonizing Methodologies: research and Indigenous People. Dunedin: The University of Otago Press; London and New York: Zed Books Ltd.

National Collaborating Centre on Aboriginal Health (NCCAH) (2007). developing an Indigenous Peer review Framework and process for an online child, family and community focused journal, reretrieved 4 February 2020, from https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/ default/files/docs/Developing_Indigenous_Framework_Process_ OnlineJournal_2007.pdf.

We asked the city if instead of brick, if we could incorporate mosaic tile into the base. With the redirected funding, we put out a “call for artists” and brought together a diverse team of local and international artists to develop artwork for the buildings that represent the four cultures. We led a collaborative multi-day charrette with the artists to generate the designs for the 32 columns on each building. We selected a Salish, African, Mayan and Chinese mask to represent the four cultures in a relief that is mounted to an inset at the top of each column, and incorporated into the flooring of the Centilia Cultural Center and the residential floors. The local artists included Cecilia Alvarez, a Cuban American, Louie Gong, a Nooksack and Chinese artist, Al Doggett, an African American artist, myself, from the Crow Tribe of Montana and Kimberly Deriana, a Mandan-Hidatsa architect. The tilework and many of the designs were developed by a team of Chicano, Mexican and Indigenous artist in Tucson, Arizona, led by Gonzalo Espinoza and Alex Garza. (Fig. 5) At the entranceway to the plaza, Roberto Maestas can be seen striding forward in full figure bronze. (Fig. 4) He stands in front of a striking assemblage of seven tubular steel poles that rise upward for several feet before bending and curling in an abstracted cloud formation high above the plaza. In the summer, water vapor mists from the formation, and multi-colored translucent panels above these clouds cast a rainbow of color onto the plaza in the sunlight. The sculpture is intended to represent the “Lifting the Sky” story with the poles holding the sky aloft. The work is by a Basque artist from Spain, Casto Solano. Solano is known for his work which combines highly realistic bronze figures and architectural scale abstract sculpture. Estela Ortega was adamant that Roberto Maestas be represented in bronze, as she pointed out

Figure 4. The sculpture by Casto Solano of Roberto Maestas and Lifting the Sky on the day of the commemoration of the sculpture in 2017. Photo by Daniel Glenn.

Figure 5. Artists and architect team at the El Centro Gala with two of the surviving members of the Gang of Four. Left to right: architect Daniel Glenn, artist Cecilia Alvarez, architect Kimberly Deriana, artist Al Dogget, Gang of Four member Larry Gosset, Jr., artist Gonzalo Espinoza, Gang of Four member Bob Santos, El Centro Board Chair Ramon Seliz, and artist Louis Gong, 2016. Photo courtesy of 7 Directions Architects/Planners.

Figure 6. Stillaguamish tribal members present their concept plan during the “kit-of-parts” site design exercise. Photo by Daniel Glenn.

there are very few people of color represented as bronze figures in the city or nationally.

The Plaza Roberto Maestas represents a form of decolonization of the city. In its origin, its design and in its function, the project represents a small piece of the city that has been carved out to serve and celebrate displaced Indigenous people and marginalized people of color. It is an intentional community, built and managed by a non-profit organization that is led and operated by empowered people of that community. It is a rare instance in which land has been reclaimed from colonizers through occupation and built into a “beloved community” through decades of work.

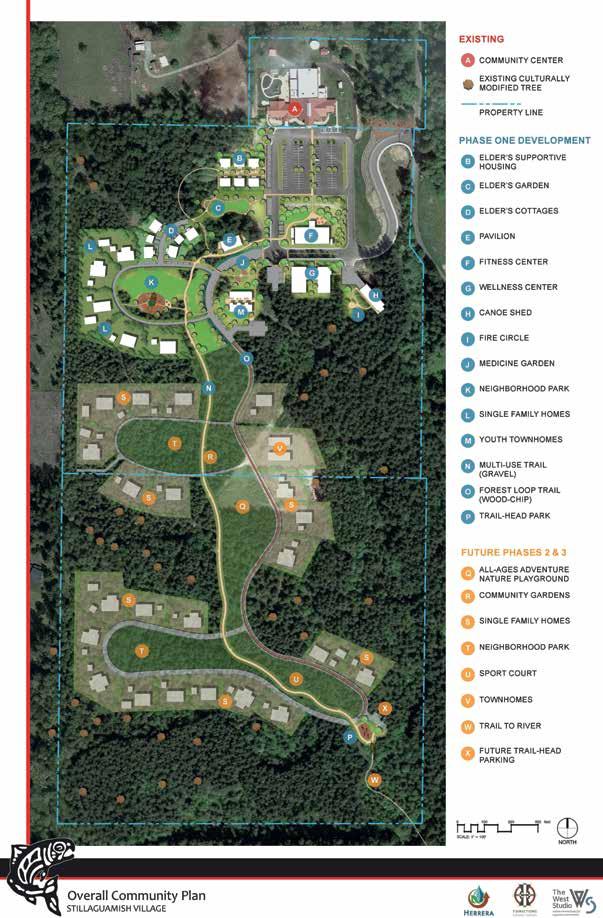

Stillaguamish Village

High above the banks of the Stillaguamish River, north of the city of Arlington, Washington, a new community is being built by the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians on eighty acres of forested land that has been reclaimed by the Tribe. The new Stillaguamish Village is part of an effort to rebuild community and culture after more than a century of displacement and the loss of their status as an independent tribe. At the time of the signing of the Treaty of Port Elliot in 1855, which marked the beginning of the reservation era in the Pacific Northwest, there were 20-25 villages along the Stillaguamish River. Like most Salish people of the region after the treaty was signed, the land of these people was taken, their villages and plank longhouses were destroyed, and they were forced onto reservations. Without being granted official tribal status, the Stillaguamish did not receive their own reservation. Tribal members were forced to disperse to

other reservations in the area. Following a fifty-year effort by Stillaguamish descendant Esther Ross, beginning in the 1920s, the tribe received federal recognition only in 1976 (Ruby & Brown, 2001). Since that time, the tribe has been working to regain lost tribal lands, beginning the effort with a small housing community built in 1986 on a site within their original territory using funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which is required by treaty to provide housing to tribal communities. In 2004, the tribe relocated members from the housing site and built the Angel of the Winds Casino near a major transportation corridor north of Seattle, Washington. With the success of this economic development effort, the tribe has been working to buy back their original lands along the Stillaguamish River. And in 2014, the tribe regained Reservation Designation on these lands. In the fall of 2015, our firm, 7 Directions Architects/Planners, was hired to lead development of a master plan for a new Stillaguamish Village on an 80-acre site along the Stillaguamish River, with a design team that includes Herrera civil engineers and West Studio landscape architects. The project is a first effort to build a contemporary version of a Stillaguamish Village in their original homelands.

The first phase of the master plan is currently under construction with completion expected in 2021. The site includes an existing community center and parking area. The remainder of the site is largely forested. Working with the Stillaguamish Tribe’s Housing Department, led by Stillaguamish Tribal member Chris Boser, we led a community-based design process that engaged tribal members in an envisioning process to determine uses for the new village and develop the design.

Figure 7. Elders Longhouse structure at the Stillaguamish Village. Photo by Daniel Glenn courtesy of 7 Directions Architects/Planners.

Master Site Plan for the

in Arlington, Washington. Rendering and design by 7 Directions Architects/Planners and the West Studio.

Figure 8.

Stillaguamish Village

Figure 23. Blue cladding.

Figure 24. Stars.

bboong, mnookmik gewe.

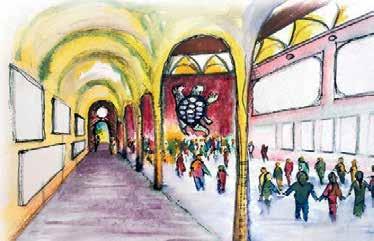

10. Spatial storytelling: moving along a journey of prediscovery, visitors are immersed in an augmented reality from Wellington to Sparks Street.

Community Kitchen – Jiibaakwegamik Kina Wiya Debendang

Our narrative continues as visitors enter the building with Elders on one side and children on the other; all generations are welcomed and at home here.

Wii-ni-aabdaajmayaang: Biindgeyaat bebaa-yaajik, getzijik mbaneyiing yaawak, binoojiinyik dash gewii oodi npaajiyiing. Kina go wiya zhanda daa-biindge miinwaa endaat yaaji da-nendam.

Spatial Storyline from Wellington Street to Sparks Street – Enaabiising Naajmowin Wellington Biinish Sparks

The history and narratives of our nations are shared with augmented reality along a public path that connects Parliament to Sparks; this colonnade may be opened or closed; windows look onto an exhibition space for dancing, drumming, singing, art.

Miikaans Parliament da-nji-maajiimat; Sparks da-konamat. Na’ii zhiwi miikaansing da-zhinoomaadim, gaabi-zhiwebak, enaajmaying gewe. Daa-nsaaknigaade maage go daa-gbaakwigaade maanda colonnade; waasechganan gewe te-noon gegoo maanpii nakmigak wii-waabmindwaa naamjik, e-dewegejik, negmajik gewe, miinwaa mzinbii’ganak mzinniik miinwaa wi dnawa nooch gegoo zhinoomaading.

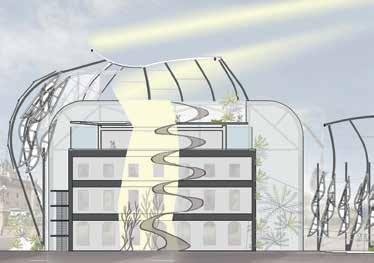

Offices Connected by Atrium – wii-waasetek kina endzhi-nakiiyaat

The inherent hierarchy of the historical building is fluidly reconnected with light; a glowing core builds kinship between earth and sky. The meeting and private spaces that encircle this core and look over Parliament inspire our representatives to speak for our nations

Mno-waasete kina zhanda bebkaan bmisgaak wiiwaabndaming kina wiya naasaap piitendaagzit. Biindgeyaate bebkaan kina wiya yaat, waabndiwak dash kina zhanda en’kiijik. Parliament debaabminaagot. Waabndmawaat wi, da-mkwendaanaawaa zhanda en’kiijik ge-zhi-gnoodmawaawaapa wiiji-Nishnaabewaan.

Figure 9. Outdoor seasonal activities welcome visitors to this garden under a shared blanket, along an axis that connects our two fires.

Figure

Figure 11. Reconnecting the earth and sky through the historical building.

Gathering of Nations Circle – Gathering of Nations Circle

At the place of connection to sky, a circular meeting space allows representatives to meet in a space that honors protocols such as pipe ceremonies. Views over Parliament connect to the outdoors with layers of roof garden.

Zhanda ge-dzhi-n‘kweshkdaadwaat bemaadzijik, waawyeyaa wii-gshkitoowaat weweni wii-naagdoowaat ezhchigeng pwaagan zgaswaanin gchi-nakmigzing. Pakwaaning waawaaskoneyin gtigaadenoon; Parliament debaabminaagot.

Rooftop Garden and Cafe – Pakwaaning Gtigaanens Miinwaa Cafe

At celebrations and events, the outdoor roof garden and cafe look directly over Parliament, while the building wrap extends gently above to provide privacy and a comfortable environment with shade and shelter.

Nooch gegoo nakmigak, Parliament dadebaabndaanaawaa eyaajik zhiwi gtigaanensing wi pakwaaning etek, bekish dash da-aagooshnook wii-bwaawaabmigwaat kina wiyan, miinwaa da-kajgaa, da-dbinwaa gewe.

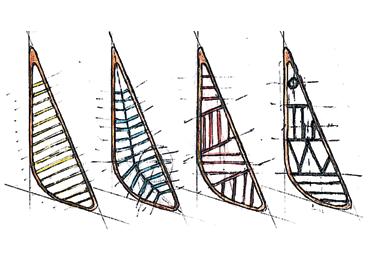

Regalia // Dbishkoo Kwe Gchitwaawkonyet Zhizzegaachgaade Maanda Wiigwaam

This wrap honors the gift and makes it our own. The ribs might be those of our mother, the decorations her skirt. All our nations are present here, each decoration gifted and returned in an ongoing cycle

Mnaadenjgaade maanda wiigwaam gaa-miin’goong, gda-daapnanaa dash maanda giinwi wii-dbendmang. Niwin pigegning ezhnaagkin, mii dbishkoo gashnaa eyaangin, wi ezhi-zzegaachgeng, mii dbishkoo wdoo-skirt. Nooch ngoji wenjiijik gonda sa Maanpii Kiin Wenzkaajik daa-zhitoonaawaa gegoo maanpii wiigwaaming waazzegaachgeng wii-tenik wiinwaa bimaadziwniwaang wenzkaanik wii-tenik maanpii Ottawa. Maamnik da-keteni wi maagweyaat, mii dash neyaap da-miindwaa, bekaanak dash miinwaa gnamaa daa-miigwenaawaa. Memeshkdoonming maagweng, mii maanda wiigwaam ezhi-zzegaachgaadek.

Displaying Indigenous material culture inspired by regalia,

Figure 12. Gathering of Nations Circle is a space for protocols such as pipe ceremony or smudge before meetings, looking out over the parliamentary precinct.

Figure 13.

gifts crafted in our communities are in constant rotation, mounted on the blanket framework facade.