His Almée (“Almeh”, 1863, Dayton, The Dayton Art Institute) features a belly-dancer performing in front of an audience of soldiers, and was shown at the Salon of 1864, causing at least as much controversy as Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863, Paris, Musée d’Orsay), first exhibited in 1865. Criticisms were not of the same order, however: Manet was too realistic, Gérôme too sensual. Nearly naked, L’Almée spreads her arms and moves her hips, bewitching her audience. Gérôme was not afraid to tackle somewhat risqué subjects, as evidenced in his showing a scene in which a woman reveals her nudity before a male audience. Linda Nochlin rightly underlines that this kind of Orientalism had little to do with any form of ethnographic research12 The veil concealing the East and the pretext of ancient history allowed Gérôme to show a certain boldness. To his advantage, he had a flawless academic technique and an exceptional work capacity. And he was not the only one to make use of the exotic seductiveness of the East. Gustave Boulanger, the Italian painter Anatolio Scifoni, and, a little later, Georges Clairin, would all do the same. These artists also knew how to create works with more understated eroticism, by employing their talent for landscape or portrait painting. At that time, there was a great demand for Orientalist fantasies, and Gérôme responded to it exceptionally well. Even Adrien Dauzats, reputed though he was for his scrupulous interpretation of the East, was commissioned by a collector to paint four works inspired by stories from The Arabian Nights. Unlike Gérôme, Fromentin appeared as a leading naturalist orientalist. An extensive traveler, he met with great success in 1863 for Chasse au faucon (“Hawk-hunting”) and Bivouac arabe au lever du soleil (“Arab Bivouac at Sunrise”).

12. Linda Nochlin, The Politics of Vision. Essays on NineteenthCentury Art and Society, Boulder, Westview Press, 1989, p. 33–59.

The East in 19th-Century Paris

13. Paul Gaudin, Essai sur Eugène Fromentin. Conférence faite le 9 décembre 1876, dans la grande salle de la Bourse de La Rochelle, La Rochelle, A. Siret, 1877, p. 9.

The poet Albert Mérat liked the second work so much that he sent the painter a sonnet. “He was cited among the greatest. During the elections for the painting juries, his name was always one of the first to come out of the ballot box [...]. Each Salon found him ever more worthy of his glory13.” Fromentin’s success did not waver. His works were considered highly realistic, yet with a Romantic spirit and style kept intact. Fromentin’s 1862 novel Dominique—for he was a renowned writer as well as a painter—marked the end of the Romantic era in French literature, and a shift towards Realism. In 1876, he was still hugely popular when he exhibited Le Nil (“The Nile”) and Souvenir d’Ezneh (“Memory of Ezneh”), two paintings he produced a few years after his journey to Egypt. They were less picturesque than his preceding ones and replete with his memories of the East.

Léon Belly devoted himself almost entirely to Orientalist ethnographic subjects after a mission that took him from Lebanon to Egypt in 1850. His work Pèlerins allant à La Mecque (“Pilgrims on their way to Mecca”), first exhibited at the Salon of 1861, was highly praised. In an ambitious format, it represents a caravan in the desert heading towards the holy city of Islam. The effect is spectacular, as the pilgrims seem to be coming towards the viewer. Victor Cochinat, in the newspaper La Causerie, judged Belly’s painting to be “striking in its brilliance and grandeur. The desert is vast, blazing beneath the fiery sun, and an assorted crowd stretches like one long ribbon from the foreground to the background, in all its oriental majesty14.” Belly impressed the Salon’s visitors once again when he presented La Mer morte (“The Dead Sea”) in 1866. The work is interesting in the way it sublimates oriental landscapes.

14. Victor Cochinat, “Causerie sur le Salon”, La Causerie, 9 June 1861, p. 4.

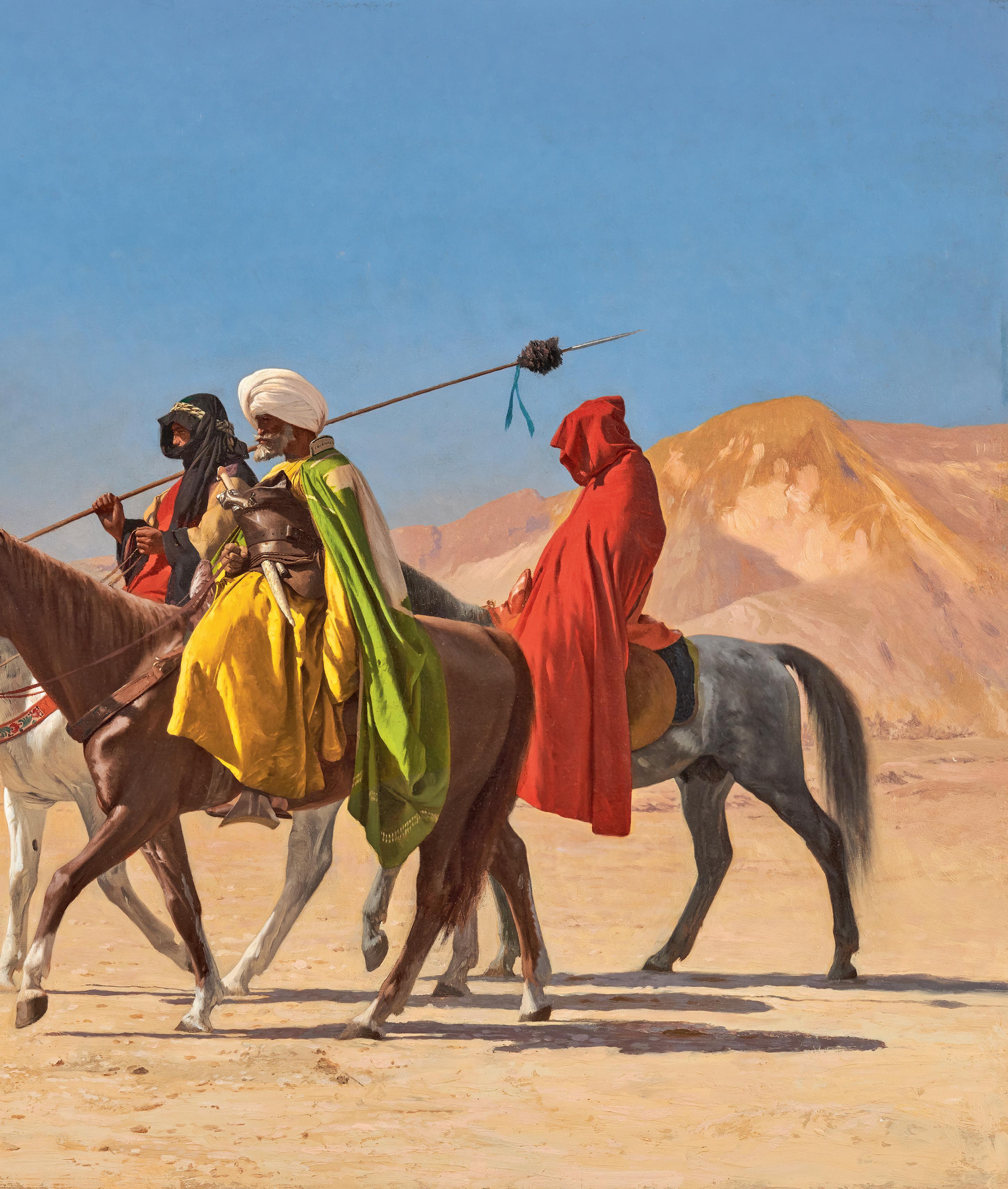

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Le Veneur (The Hunter), 1871, oil on canvas, 33 × 25 cm. Private collection

The East in 19th-Century Paris

Travel literature began to develop in the 1830s, before proliferating thanks to the modernization of transport towards the East. The three volumes published by Olympe Audouard following her journey to Egypt—Le Mystère des sérails et des harems turcs; lois, mœurs, usages, anecdotes (“The Mystery of Turkish Siraglios and Harems; Laws, Mores, Customs, Anecdotes”, 1863), Les Mystères de l’Égypte dévoilés (“The Mysteries of Egypt Unveiled”, 1865) and L’Orient et ses peuplades (“The East and its Peoples”, 1867)—provided forbidden pleasures. The author, who made it a profitable subject, put her male readers under the impression that they were entering the prohibited world of harems. BenjaminConstant, a painter whose works often featured Eastern women, may have known about such publications. Traveling novelists followed in the wake of Chateaubriand, the author of the widely praised Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem (“Journey from Paris to Jerusalem,” 1811), by publishing their own accounts. Alphonse de Lamartine in 1835 and Gérard de Nerval in 1851 both published works entitled Voyage en Orient (“Journey to the East”). An aspiring traveler like Gustave Flaubert could not have disregarded them; whatever the case, he had in his luggage the ethnographic study An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836) by Edward William Lane, an essential book on the subject. When Eugène Fromentin was preparing for his journey to the East, his mind was also full of these readings, Chateaubriand in particular. In his turn, he provided an account of his experience in Un été dans le Sahara (“A Summer in the Sahara”, 1856) and Une année dans le Sahel (“A Year in the Sahel”, 1859), useful sources for future travelers. His friend Narcisse Berchère did the same with Le Désert de Suez. Cinq mois dans l’isthme (“The Desert of Suez: Five months in the Isthmus”, 1863). It was only at that time, in 1861, that the first tourist guide to the East was published by Hachette in their Joanne collection—too late for many artists to benefit from reading it.

The artist’s travel account had become a fashionable genre, as shown by these examples stretching across several decades: Quinze Jours au Sinaï (“Fifteen Days in the Sinai”, 1839) by Adrien Dauzats (the work was actually written by his friend Alexandre Dumas père from his memories, notes and drawings); Voyage d’Horace Vernet en Orient (“Horace Vernet’s Journey to the East,” 1843) by Antoine Goupil Fasquel; and Le Fayoum, le Sinaï et Pétra. Expédition dans la Moyenne Égypte et l’Arabie Pétrée sous la direction de J. L. Gérôme (“Faiyum, Sinai and Petra: Expedition to Middle Egypt and Arabia Petraea, overseen by J. L. Gérôme”, 1872) by the painter Paul Lenoir. There was also a trend for illustrated magazines such as L’Artiste or Le Tour du monde to publish articles by Orientalist painters.

Photograph Collections

Around 1850, all those passionate about the East—and particularly Egypt—must have been thrilled when the first great photograph albums were published. Photography was then in its infancy. The operators—pioneers in their field— went on site equipped with extremely cumbersome devices and a laboratory’s worth of chemicals, not to mention the glass plates they also had to carry. They went east, to Egypt or Palestine, coming at first from France as much as from Great Britain. The photographs they brought back were often of invaluable help to painters. Eugène Fromentin employed a series of photographs by Wilhelm Hammerschmidt in order to complete his painting titled Sur le Nil (“On the Nile”). The photographers were also sometimes themselves influenced by the paintings of their artist friends, as is shown by the strong aesthetic connections between certain British photographers, like Frank Mason Good, and the PreRaphaelites. The photographs sometimes brought to mind poses in works from Salons.

Maxime Du Camp, Groupe de colonnes du palais de Louxor, Thèbes (Group of Columns from the Luxor Palace, Thebes), circa 1849–1850, photograph.

Anonymous, Femme voilée dans un palais (Veiled Woman in a Palace), circa 1920, photograph.

The East in 19th-Century Paris

All artists from the second half of the 19th century were interested in photography, either because they called it into question (Delacroix and Baudelaire), or because they admired and practiced it (Auguste Bartholdi, Edgar Degas).

Photographers and painters often met at Salons and world’s fairs, or even in the East. For instance, Eugène Fromentin, Narcisse Berchère and Jean-Léon Gérôme traveled to Egypt with the photographer Gaston Braun (who was representing his father Adolphe Braun) for the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Travel photography made rapid progress thanks to improvements in equipment and technique. By the 1880s, the invention of phototypes had helped reduce the cost of production and therefore publication. Photography was being increasingly used in illustrated magazines and books. At the end of the century, local photographers began to emerge in the Mediterranean East, and publishers could sell cheap images more easily in Europe, enabling each and every one to recreate their own imaginary landscape at home.