Ibsen’s Act of Kindness

Fairy-tale Forest Magnificent Mess

Snapping the Selfie

Hiding Out

Munch’s Garden

Ibsen’s Act of Kindness

Fairy-tale Forest Magnificent Mess

Snapping the Selfie

Hiding Out

Munch’s Garden

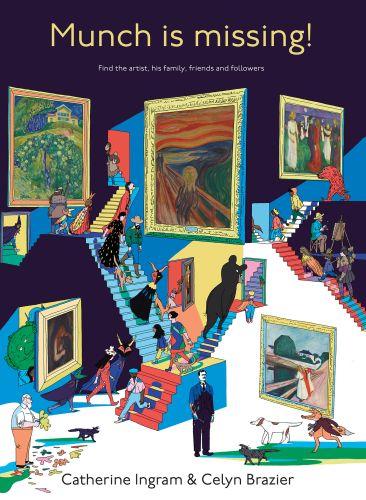

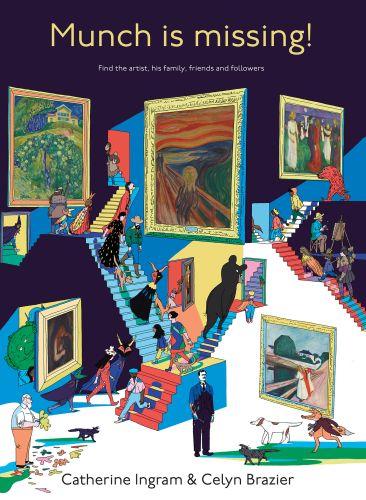

Edvard Munch was a brave artist who was not afraid to express his emotions. In his most famous work, a pale figure cries out in despair. This raw honesty may explain his global appeal. As King Harald of Norway once said, ‘People all over the world feel a connection to Munch.’

Sensitive to the natural world, Munch chose to eat a mainly plant-based diet, and painted seaside scenes bursting with life and mysterious forests filled with wonder. At the same time, the trailblazing artist embraced the latest science and technology and experimented with film as well as photography. Indeed, he is believed to be the first artist ever to take a selfie!

He was also a very messy artist, partly stemming from his innovative nature and relentless drive to create art. As a result, Munch produced over 28,000 works, most of which are now on view or stored in the Munch Museum in Oslo.

Join us in celebrating this iconic artist by delving into our 12 vivid worlds that explore aspects of his creative life. Seek out Munch, then find writers, cultural figures and other artists who have been inspired by him.

Åsgårdstrand meant a great deal to Edvard Munch. In the summer of 1885, he met his first love, Milly Thaulow [1], there. Later, he took many summer holidays in the coastal village, and when he became a more established artist, he bought a fisherman’s cottage [2] near the Åsgårdstrand shoreline. He made friends there too, and painted his neighbour Ingse Vibe [3]. Life was not always peaceful, however. In 1898, Munch became romantically involved with a woman called Tulla Larsen [4]. They had a very difficult relationship. The last time they met was in Åsgårdstrand, where they argued and broke up in 1902.

Munch’s Dance of Life captures the shoreline of Åsgårdstrand. In the painting, three women stand out because of their dramatic clothing and their black [5], white [6] and red dresses [7]. As we can see in the illustration, the woman in the red dress is dancing with a young man. Munch used the colours expressively to say different things about the women. The white dress is worn by a younger woman and symbolises her youth. In contrast, red is a fire colour, while black has the beauty of the night.

Artists often bring colour into paintings through people’s clothes, like Munch did. Hidden in our illustration is the Netherlandish artist Jan van Eyck’s [8] red turban that he wears in his famous self-portrait. One can spot Marina Abramović’s [9] dramatic red gown, which she wore for a performance at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The colour red has inspired many artists. The Abstract Expressionist artist Mark Rothko’s [10] deep maroon red paintings are a prime example.

White is also a colour that has fascinated artists. Hidden in the illustration is the girl from James Whistler’s painting Symphony in White [11]. She is wearing a long, white dress. Scottish artist Alison Watt’s [12] paintings of white fabric are also noteworthy. Black is a magical colour too. Hiding in the illustration is the Surrealist painter René Magritte’s [13] signature black overcoat and black bowler hat. The artist Francisco de Goya was fascinated by the colour black and painted a whole series of black paintings. Can you spot his Great He-Goat [14], featured in one of his black paintings? Kazimir Malevich’s [15] painting of a single black cross became an iconic image of the 20th century. A clue to help spot this artist: he is wearing a red beret.

Munch’s Dance of Life captures Norway’s magical Midsummer nights, when the natural light persists and lights up the moonlit sky. Can you spot the pillar of moonlight [16] which Munch painted in many of his works? Perhaps he was inspired by the Midsummer night celebrations he attended as a child, which he enjoyed enormously. In Norway, the Midsummer bonfire is an annual tradition, and several Norwegian artists have depicted the event. Nikolai Astrup’s [17] revellers, painted in local costume, dance around a bonfire.

Fire has captivated many Norwegian artists. Munch himself painted several house fires. Relishing the beauty of fire, Gerhard Munthe’s flame-headed women [18] in one of his tapestries stand out. Outside of Norway, many artists have been inspired by fires too. The English painter John Everett Millais’s group of young girls gathering autumn leaves [19] for a bonfire is a poignant depiction, while the Belgian artist James Ensor’s [20] preference for firework blazes is equally captivating. A clue to finding Ensor: he is dressed in a particularly flamboyant hat.

Fire can signify such different things. While Gerhard Richter’s [21] serene paintings of burning candles evoke calm, other artists have explored fire as a destructive force. Yves Klein’s [22] scorched patterns on canvases showcase a dynamic approach. A few artists have gone further and set fire to artworks. Damien Hirst’s [23] public burning of hundreds of his iconic dot paintings was dramatic, and the musician Serge Gainsbourg’s [24] provocative burning of a banknote on TV caused a stir!

In our illustration, apart from poor Tulla, everybody seems to be enjoying this Midsummer night. Can you spot all the children in their dress-up costumes, dancing their great moves? Who do you think is the best dancer?

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaagh! Edvard Munch’s The Scream was a long-awaited release, permitting us all to express our most troubled thoughts. Many believe there is only one version of the image, but Munch actually created many.

Artists have striven to capture such intense emotion. Egon Schiele [1] painted himself screaming, and in a tribute to Munch, Tracey Emin [2] recorded herself on the jetty of Åsgårdstrand, wailing for an entire minute. Marina Abramović’s [3] response was to make a metal frame based on the dimensions of Munch’s painting. She erected it at the spot where he heard the echoing scream that inspired his work. At the opening ceremony, Abramović invited 300 people to scream through the frame.

Many other artists have been inspired by The Scream too; the painting has been interpreted in very different ways. Francis Bacon’s screaming popes [4] are tortured. In Henry Taylor’s Screaming Head [5], the face is taken over by the wailing mouth which cries out at the appalling injustice towards people of colour.

Peter Doig, interested in the idea of reverberating sound, painted Echo Lake, where a policeman shouts [6] into empty space. Then, there is Sergei Eisenstein’s film Potemkin, which has that memorable close-up of a woman screaming on the now famous staircase [7] in Odesa.

Baby screams are one of the first signs of life – and artists have depicted many screaming babies! The sculptor Gustav Vigeland made Angry Boy [8], a much-visited statue in Oslo’s Frogner Park. Inspired by Munch’s Scream, Roy Lichtenstein created a silkscreen of a wailing baby [9]. There is also bawling Max [10] from Maurice Sendak’s children’s book Where the Wild Things Are

There are many references to Munch’s screaming figure in popular culture. Child actor Macaulay Culkin [11] performs the scream for the film poster for Home Alone. And of course, there’s the iconic mask [12] worn in the cult film Scream, which many children in the illustration are wearing.

Munch’s Scream expressed the mood of his time. The early 19th century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer [13] anticipated the painting when he talked of the limits of art, and its inability to capture a scream. Around the same time, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche [14] denied there was a God, leading many people to despair. With his large moustache, he is easy to spot. Meanwhile, the founding thinker of depth psychology, Sigmund Freud [15], was using therapy as a way of processing difficult emotions.

One of Freud’s students, Wilhelm Reich [16], lived in Norway for a while, studying how we seem to store traumatic experiences in our bodies. Years later, the psychotherapist Arthur Janov [17] argued that screaming could release our hidden traumas. He published the book Primal Scream Therapy, which he sent to John Lennon [18] and Mick Jagger [19]. Lennon and Yoko Ono [20] both underwent primal scream therapy and brought screaming into their music and art performances. Musicians Ari Up [21] and Patty Waters [22] also scream out through their music. Artist and musician Gina Birch [23] recorded a video of herself screaming for three minutes to express her loneliness.

Munch’s Scream resonates with the resounding cries of young activists like Malala Yousafzai [24] and Thandiwe Abdullah [25] at public rallies. The young Syrian activist Bana al-Abed [26] posted images of herself online, holding up placards that express her cries for help. One is reminded of artist Gillian Wearing, who stopped passers-by on the street and asked them to write their inner feelings on a placard. In response, a policeman held up a sign which read ‘Help’ [27], while a businessman’s placard read ‘I’m Desperate’. These are silent screams. Munch himself painted a little girl in a red dress [28] covering her ears, perhaps trying to silence her inner scream.

Andy Warhol [29] was interested in The Scream’s iconic status – he made a series of 15 prints based on the image. The fame and value of Munch’s Scream has attracted thieves, and the artwork has been stolen several times. In 1994, robbers [30] erected a ladder and were in and out of the National Gallery in Oslo in 50 seconds. Scotland Yard detective Charles Hill [31] went undercover and managed to find the painting.

Imagine if the painting had been lost forever. That would have made anyone scream!

Welcome to the world of the selfie! Many consider Edvard Munch to be the originator of the selfie. The artist made the strategic move of turning his Brownie camera round, pointing it towards himself, and capturing his own image.

Many photographers have caught images of themselves in reflective surfaces. The recently discovered photographer Vivian Maier [1] photographed her reflection in shop windows. Linda McCartney [2] made several self-portraits in front of mirrors. In one of them, she poses with her husband – Beatles member Paul McCartney – and their baby [3].

Before the camera was invented, reflections were the only way to see oneself, but their images are temporary. Caravaggio painted the Greek mythological character Narcissus [4] who fell in love with his reflection in a pool. Many artists have used pools of water in their portraits. David Hockney [5] staged many portraits around swimming pools, and for his video Beautiful People David Wojnarowicz [6] walked into a lake wearing a red dress.

In many ways, the camera democratised the self-portrait. Anybody could snap a selfie! In 1927, the photobooth was invented, and people could slot a coin into the machine and collect their four-frame ‘selfie’ strip. In the early days, assistants were there to help and suggest poses. The photobooth quickly drew the attention of the writer André Breton, who gathered up the Surrealist artists Salvador Dalí [7], René Magritte [8] and Yves Tanguy [9], and marched them down to the booths on the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

The photobooth soon became fashionable, and even Jackie and John Kennedy [10] had shots taken on their honeymoon. The artist most closely associated with the photobooth is Andy Warhol [11]. Warhol famously said he wanted to be a machine. Delighted by how the booth automatically generated self-portraits, he had portraits taken of himself and his doppelgänger, actress Edie Sedgwick [12] When the rich art collector Ethel Scull [13] asked him to make a portrait of her, Warhol had her pose in a photobooth. In the 1980s, Warhol preferred a Big Shot polaroid which he used to capture many cultural icons, including Nico [14], Jean-Michel Basquiat [15] and Lou Reed [16]. Queen Sonja of Norway [17] was fascinated by Warhol and met him on a trip to New York, where Warhol shot a polaroid of her which he made into a vibrant silkscreen.

Artists have used photography to explore their identity. Conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp photographed his alter ego Rrose Sélavy [18]. Zanele Muholi [19] uses portraiture to explore their identity as a black queer person. Taking a different approach, Carrie Mae Weems [20] has staged scenes to expose traditional gender roles. For her famous Kitchen Table series, she acted out typical female roles in the home. Cindy Sherman [21] and Diane Arbus [22] have also used the self-portrait to question female identity.

Today, we can take selfies on our smartphones. This can be fun, but it also creates anxiety as people want to look perfect. The desire to be beautiful and impress people has always existed. Artists sometimes use expensive materials to add grandeur. The Pop artist Pauline Boty [23] created a self-portrait in the timeless medium of stained glass. Other artists want to look more up-to-date and cool. For his self-portrait, Peter Blake [24] posed as the rebel artist in his denim jacket plastered with badges. The Krautrock band Kraftwerk [25] wore super slick outfits for one album cover.

Portraiture and selfies can also be candid, even shocking. Rembrandt van Rijn [26] painted his blemished skin and bulbous nose, and Frida Kahlo [27] painted in her monobrow and moustache. Artists often reveal their state of mind in selfportraits. Gustave Courbet [28] painted himself in a state of confusion. In one of Vincent van Gogh’s [29] self-portraits, he appears dejected and injured, with a bandage around his ear. In contrast, Pablo Picasso [30] often dressed up and acted silly for a photo.

How do you stage your selfies? Do you make a funny face? Yayoi Kusama’s infinity rooms [31] offer a perfect environment for a magical selfie with endlessly repeating images of yourself. In our illustration, a couple of kids have found their way into Yayoi’s room, where they are snapping their selfies.

When the Nazis invaded Norway in 1940, the art collector Thomas Olsen hid Edvard Munch’s paintings The Scream and The Dance on the Beach [1] in a remote barn in a forest in Norway. They remained there for the rest of the war. Olsen had good reason to hide these paintings away: seven years earlier, the Nazis had deemed Munch’s art to be morally lacking and removed 83 of his works from German galleries. Modern artists bravely continued to work during the war. One artist, Emil Nolde [2], tried to find favour with the Nazis, but he was the exception. The Nazis began persecuting artists of Jewish descent. The textile artist Gunta Stölzl [3] and Expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz [4] were forced out of their teaching jobs.

In 1933, the Nazis closed the Bauhaus art school on the basis that its teaching was fundamentally ‘un-German’. It was a terrible moment for modern art. The school was left abandoned. The architect Walter Gropius [5] had designed the iconic building and the world-famous artists Wassily Kandinsky [6] and Paul Klee had both taught there. Part of the visionary ethos of the Bauhaus had been to bring art to everyday life, and lessons included furniture design and textiles. Anni Albers [7] pioneered modern textiles and Marcel Breuer’s [8] chairs have since become design classics. Both had been teachers at the Bauhaus, but were now on the run, hiding from the Nazis, desperate to find a country where they would be safe, and free to create their art.

The Nazis’ attack on modern art continued. In 1937, the cultural minister Joseph Goebbels [9] organised a show of Degenerate Art. Modern paintings like Franz Marc’s Blue Horses [10] were mocked. It was a dangerous time. Photographer Robert Capa [11] and the painter George Grosz [12] left the country, and so did artists Sophie-Taeuber Arp [13] and Paul Klee [14]. The latter can be spotted escaping in a hot air balloon, which features in one of his paintings. Kurt Schwitters [15] escaped to Norway, where he created one of his Merzbaus, a small shack filled with sculpture and found objects. A little girl called Judith Kerr had to leave her home too. Kerr became a renowned writer and illustrator, and she can be spotted with The Tiger who Came to Tea [16], a much-loved character from one of her classic children’s books.

Many Jewish art dealers had art collections seized or bought for pitiful amounts. The art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt [17] bought looted artwork and amassed an enormous personal collection, including works by Munch, which he passed on to his son Cornelius [18]. Cornelius hid this incredible art collection away until 2014, when the police discovered it. Some of the works wrongfully taken from Jewish families were returned. Other Jewish art collectors were less fortunate. Lea Bondi [19] had a treasured painting by Egon Schiele confiscated by the Nazis, and never saw it again.

When World War II broke out, the Nazis inflicted further damage on the art world. Hitler dreamed of having a museum of classical art. As the Nazis invaded countries, they stole old artworks. The high-ranking Nazi Hermann Göring [20] scoured the looted art for the best pieces to display in the castle where he lived with his pet lions. By 1940, the Nazis occupied France, creating anxiety amongst the artist community there. The Surrealist artist Max Ernst [21] was captured, but managed to escape. Meanwhile, the artist Leonora Carrington [22] fled to Mexico. She can be spotted riding away on a horse, an animal which appears often in her paintings.

Some artists refused to be pushed out. Pablo Picasso [23] remained in Paris. Many who stayed became involved in the resistance movement which wanted to defeat the Nazis. Albert Camus [24] wrote for a newspaper that was condemning the Nazis’ actions. Singer Josephine Baker [25] became a spy, transporting secret messages in music sheets to the allies. A crucial resistance worker was Rose Valland [26]. She worked at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris, where looted art was sent. Unknown to the Nazis, she understood German and listened in on their conversations, and noted where they were hiding the art. Because of her efforts, much of the stolen art was recovered after the war.

Munch is Missing!

First Edition 2025 Munchmuseet

All rights reserved © Catherine Ingram © Celyn Brazier

All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

www.munchmuseet.no

ISBN: 978-82-8462-026-8