Alfredo Reyes / Claudia Bodinek (eds.)

MAGNIFICENCE of ROCOCO

Kaendler’s Meissen Porcelain Figures

WAWEL ROYAL CASTLE

RÖBBIG MUNICH

arnoldsche

Alfredo Reyes and Claudia Bodinek (eds.)

MAGNIFICENCE

ROCOCO

Kaendler’s Meissen Porcelain

Figures

The Director dr hab. the exhibition and cordially invite you WYSPIAŃSKI’S

Viviane Mesqui, Sèvres 14 Rococo Table Decoration amongst the Nobility

Dirk Syndram, Dresden

38 The Saxon-Polish Elector-Kings: Newly Acquired Magnificence and the Invention of European Porcelain

Christian Lechelt, Höxter

60 Johann Joachim Kaendler and his Collaborators at the Meissen Manufactory

Julia Weber, Dresden

76 “Auf Indianische Arth”: Figural Representations of Asians and Ottomans in Meissen Porcelain

Dorota Gabryś, Cracow

108 Wawel Royal Castle and its Porcelain

CATALOGUE

132 The Nobility – Wilko Beckmann, Düsseldorf

176 Animal Fights and Hunting – Claudia Bodinek, Munich

194 Commedia dell’arte – Katharina Hantschmann, Munich

234 Peoples and Animals of Foreign Lands – Vanessa Sigalas, Hartford, CT

282 Ordinary People – Claudia Bodinek, Munich

318 The Monkey Band – Anne Forray-Carlier, Paris

330 Birds – Julia Weber, Dresden

348 Mounted Porcelain – Marie-Laure de Rochebrune, Versailles

372 Showpiece Vases – Julia Weber, Dresden

378 Notes on the Catalogue and Bibliography

381 Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

The eighteenth century is undoubtedly a fascinating period in European history; often referred to as the Age of Taste, the Age of Conversation or the Age of Sophistication, it is also sometimes known as the Age of Opposites or Age of Change. The exhibition we are honoured to open at Wawel Royal Castle fits all these epithets perfectly. It is an exhibition worthy of being called a monograph of the oeuvre of Johann Joachim Kaendler (1706–1775), a grand master of design at the Meissen manufactory whose works defined the meaning and rank of porcelain in the eighteenth century.

At that time Meissen porcelain was an indicator of exceptional social status, and it remains so today. In the eighteenth century, collections of porcelain were synonymous with magnificence and splendour – a sign not only of wealth but also of the uniqueness of the owner. Table services and decorative figures and figural groups were an essential element of social life and can even be described as significant staffage to the decorum of court life. Their works were an indispensable element of court culture and visual propaganda, not only at the courts of rulers and the high aristocracy but also – within the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian-Saxon Commonwealth – in small noble residences often located in distant provinces of the country (as evidenced by numerous archival inventories).

The wonderful diversity and freedom of the figural porcelain in the exhibition corresponds with the definition proposed years ago by Professor Mariusz Karpowicz when he referred to the eighteenth-century art of the Polish-Saxon state as a “triumph of free imagination”. And it is undoubtedly a remarkable treasury of fantasy and creativity.

I would like to extend my most sincere gratitude to all the private collectors who kindly loaned their valuable artworks, as well as to Hetjens – Deutsches Keramikmuseum and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

I also wish to express my particular thanks to Mr. Alfredo Reyes, whose great dedication and commitment has been fundamental to this project, and to the curators of the exhibition, Dr. Claudia Bodinek of Röbbig München and Dorota Gabryś of Wawel Royal Castle, who have taken care of the works so generously put on loan. I am also most grateful for the contribution made by Professor Dr. Dirk Syndram, who supported the whole project with professional knowledge and kind advice.

I would also like to thank Professor Dr. Marion Ackermann, director of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and Dr. Julia Weber, director of the Porzellansammlung, for the loan of a very intricate vase decorated with guelder rose florets. The creators of the exhibition’s scenography, Pier Luigi Pizzi and Massimo Pizzi Gasparon Contarini, deserve

recognition and gratitude for their excellent work, which they accomplished with considerable technical help from Giacomo Andrea Doria. This spectacular exhibition would not have been possible without the coordination and involvement of Kama Guzik, Lidia Mróz and Andrzej Głowacz with the team at Wawel Royal Castle, who have made the dream come true. An honourable mention also goes to Bettina Lorenzoni for supervising the exhibition’s grand opening.

Andrzej Betlej,

Ph.D. Director of Wawel Royal Castle, Cracow

ROCOCO TABLE DECORATION amongst the NOBILITY

8: Commedia dell’arte series for Johann Adolf II, Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels: sixteen figures from the series. Models by Peter Reinicke and Johann Joachim Kaendler, Meissen, 1744. H. up to 15.5 cm. Private collection. See also cat. 44. © Christian Mitko, Munich

Maria Josepha and Friedrich August, the future August III, which concluded with the festivity of the miners, placed under the aegis of Saturn. The series of eight figures of miners ordered much later by August III and modelled by Kaendler and Reinicke around 1748–1750 from engravings made by Christoph Weigel (1654–1725) after drawings by Heinrich Christoph Fehling (1654–1725) not only evokes a sector of the economy that was of major importance for eighteenth-century Saxony but also recalls the parade of miners staged in Dresden in 1719 as part of the festivities on the occasion of the Austro-Saxon wedding (fig. 11).

The court jesters likewise made a contribution to providing entertainment in the course of daily life. They also inspired the Meissen manufactory, whose modellers made a variety of figures of them. Amongst the best-known jesters were Joseph Fröhlich (1694–1757) and Gottfried Schmiedel (1700–1756), who were represented together in comic groups such as that of Fröhlich and Schmiedel with a mousetrap (fig. 12).

Finally, many figural groups showcased the refinement of court society through their luxurious costume, coiffures and numerous accessories. The meticulous representation of the costume allowed for a certain measure of fantasy, as the painted decoration permitted great liberty in the renderings. The artists simply drew their inspiration from the Dresden court, a place where riches were lavishly deployed and the clothing was luxurious and diverse, as exemplified in The hand-kiss (fig. 13).

CONCLUSION

Whether at court or in town, the richness and diversity of the three-dimensional décors on grand dining tables were a true symbol of the eighteenth century and a mirror of contemporary society, the refinement of which was the origin of numerous porcelain masterpieces. Thanks to porcelain’s aesthetic and technical characteristics alike, the material came magnificently into its own on the dining table, where it beguiled all those who beheld it and created veritable spectacles to accompany lavish banquets. The porcelain figures and groups have contributed greatly to recreating a miniature representation of a society now long since vanished – a society which they themselves kept amused and made fun of at the same time.

The commercial success of these figures, and most notably that of the creations of the Meissen manufactory, contributed to their becoming famous throughout Europe and to their being admired in other places than just the dining table. They were also used in combination with ormolu mounts to enhance lights or pendule clocks, and they continued to delight the eye as independent ornaments in the houses of connoisseurs with a taste for luxury and refinement, sometimes forming part of whole rooms or cabinets devoted to the display of porcelain pieces. The figures outlived the eighteenth century by far, because their very success stimulated the manufactories, particularly Meissen, to bring many of the models back into production for clienteles that were different from the original patrons but equally fascinated by these masterpieces of porcelain sculpture.

Vault at the Dresden Residence: the Golden Coffee Service (Goldenes Kaffeezeug) made by the brilliant Dresden court jeweller Johann Melchior Dinglinger (1664–1731) together with his brother between 1697/98 and 1701 (fig. 14).

In December 1701 the elector-king ordered his court jeweller to bring the Golden Coffee Service to Warsaw immediately after its completion and – “bey verlust Dero hohen Gnade” (on pain of falling out of favour) – to present it to him “vor aller erst” (first, before all others). Even by the standards of the time it was an unusual and costly work of craftsmanship. The forty-five vessels and the two-part étagère of gilded silver and gold were accompanied by the gilt presentation stand and further precious items. It was not only his love of treasury art and eagerness to see such an unusual work that impelled Augustus to have the Golden Coffee Service brought to the royal castle at Warsaw but also political calculation. By displaying its artistic magnificence and ostentatious value he was attempting to impress the nobility, whose loyalty was wavering in the face of the Swedish invasion. For reasons of state Augustus was also willing to set the price for the service and the other precious items at 50,000 thalers. Along with the unique service, he also took possession of a casket in the shape of a silver-gilt basket holding richly enamelled flowers, a bracelet with

seventeen large, thirty-six medium-sized and thirty small diamonds together with a mirror, a writing set and a writing chest “with all kinds of cut stones and beautifully painted”.11 The four last pieces were probably intended for Augustus to use as princely gifts, since with the exception of the basket of flowers they no longer appear in the inventories of the Dresden collection.

The Golden Coffee Service, Dinglinger’s masterpiece, is a key work for the future invention and development of Meissen porcelain. In the form of an opulent service presented on an étagère, the set with its many pieces speaks eloquently of the delight taken in the enjoyment of the exotic beverages of tea and coffee that were currently becoming fashionable in Europe. Around 1700, ensembles of specialized dinner and coffee services with harmonizing designs began to revolutionize the culture of the dining table. The extensive use of pure gold for the majority of the vessels and the decoration of the coffee set with “more than 5,600 diamonds in addition to many coloured stones” imbued this cabinet piece with a prestigious and kingly aura. Moreover, eight years before the invention of European hard-paste porcelain, the Golden Coffee Service gave its owner and others who saw it an idea of the potential appearance of porcelain in the European taste.12 This applies

CATALOGUE

10 THE OPERA SINGERS

Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and his team, c. 1750

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1750

LADY: No mark

H. 20.5 cm, W. 27 cm

GENTLEMAN: Faint crossed swords mark in underglaze blue

H. 24 cm

LITERATURE: Menzhausen 1993, pp. 120–123.

Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, pp. 516–519, no. 197.

Figures of two opera singers in theatrical poses performing a duet. The lady wears a wide pannier, richly ornamented and painted with purple bouquets of flowers. A lilac bodice with a train and a long drooping veil complete her dress. Her counterpart appears in a plumed helmet, cuirass and a skirt known as a tonnelet, as was customary for actors in the eighteenth century. Each standing on a base embellished with rocailles and applied with flowers and foliage.

The group has been interpreted as depicting Madame de Pompadour and the Vicomte de Rohan, singing a duet from Acis and Galatea, an opera by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687), during an amateur performance at Versailles in 1749. This interpretation is based on a lost original image by Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger (1715–1790), handed down in a later reproduction by Adolphe Lalauze (1838–1906) entitled Madame de Pompadour jouant Acis et Galathée devant Louis XV et sa cour 6

The popularity of porcelain figures depicting singers reflects the high status of opera at the Dresden court. A new opera house had been built next to the Zwinger palace in 1718/19, during the reign of Augustus the Strong, and its interior was remodelled in 1738 and again in 1747.

For another group of opera singers modelled by Kaendler in March 1744, see p. 29, fig. 9 in the present volume.7 DG

6 Illustrated in: Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, p. 519, fig. 196.

7 Andres-Acevedo 2023, pp. 164–165, no. 457, and p. 287, no. 178.

Model probably by Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1748

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1748–1750

No mark H. 15.2 cm

GRAPHIC SOURCE: See fig. 72 below LITERATURE: Wallwitz 2006, pp. 146–149, no. 26. Exh. cat. Dresden 2010, p. 324, no. 369.

Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, p. 432, no. 140. Sigalas / Chilton 2022, p. 445, no. 136.

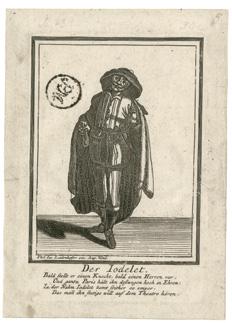

Figure of a standing man in a black robe and trousers with golden stripes, in which the white cloak forms a kind of foil. He is also wearing a black hat with a wide brim on his head. The raised right index finger and the purse in his left hand are his distinctive features.

The French actor Julien Bedeau (1586–1660), one of the most famous comedians of his time, created the stage character of Jodelet, a cheeky and greedy but somewhat simple-minded servant. The role name soon became Bedeau’s nickname and several comedies were written around the character of Jodelet.

The Meissen archive possesses an engraving made before 17148 that shows Jodelet in his characteristic habitus. The caption reads:

“Sometimes he plays a servant, sometimes a master, And all Paris holds him in high esteem for this reason, Yes, the name Jodelet has so come up since then That people constantly want to hear him at the theatre.” 9

8 Dated after the Augsburg publisher Philipp Jacob Leidenhoffer named on the print, who died in 1714.

9 “Bald stellt er einen Knecht, bald einen Herren vor, Und gantz Paris hält ihn deßwegen hoch in Ehren, Ia der Name Iodelet komt seither so empor, Das man ihn stetiges will auf dem Theatro hören.” English translation quoted from Sigalas / Chilton 2022, p. 445.

FIG. 72: Der Iodelet Re-engraving by an unknown artist, before 1714, after Abraham Bosse (1602–1676), Iodelet, c. 1645. Plate 151 × 100 mm. Meissen archive, inv. VA 1644. © Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Meissen GmbH, Historische Sammlungen

12 THE GERMAN FRENCHMAN

Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler, 1746

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1746

Crossed swords mark in underglaze blue H. 20 cm, W. 22 cm, D. 17 cm

WRITTEN SOURCE: Taxa Kaendler, entry 242 (Rafael 2009, p. 66)

LITERATURE: Berling 1900, p. 69, fig. 77 and p. 87 (this specimen). Andres-Acevedo 2023, p. 302, no. 242.

A group consisting of three figures. A man who has fallen on one knee looks in horror at a lady who is about to slap him in the face. Behind, another woman swinging a fishbone skirt high above her to hit him. A white table to his left has been knocked over and there are broken porcelain pieces lying around.

With this group of figures, Kaendler had taken up a highly topical subject that must have been on everyone’s lips at court: On the occasion of St Joseph’s Day in 1746 (25 March) – the name day of the Saxon Electress Maria Josepha – the French-German dialect poet Johann Christian Trömer (1697–1756), known as “Der Deutsche Franzos”, recited a satire entitled Ueber die Fischbehnröcke (About fishbone skirts), in which he is beaten “as an enemy of fishbone skirts” by two ladies, as Kaendler described in his Taxa. DG

42 PAIR OF GROUPS: TIGER AND LION HUNT

Models probably by Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1758/59

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1758–1760

Crossed swords mark in underglaze blue (both)

H. 18.8 cm, W. 22.7 cm, D. 13.2 cm (tiger hunt); H. 19.3 cm, W. 25.4 cm, D. 17.5 cm (lion hunt)

LITERATURE: Albiker 1935, p. 61.

Albiker 1959, no. 194 (lion hunt only).

Exh. cat. Moritzburg 2005, pp. 73–74, no. 18 (lion hunt only).

Weber 2012, pp. 38–39 and p. 41.

Counterparts. Flat oval bases, densely decorated with applied leaves and blossoms, one with a tigress, the other with a lion, each being attacked by three hunting dogs. Both big cats have turned their heads backwards in defence, a leafy tree stump supporting their bodies. All the attacking dogs in different poses, their lips pursed menacingly. Painted in natural colours with areas left white.

Both groups are based on watercolours made in connection with an order from the Parisian marchand-mercier Michel Joseph Lair (1732–1758). The corresponding sheets bear the note “Lair N0 - 53: 1758”, the Meissen mould numbers (2694 and 2698, resp.) and the costs for making mouldings, assembling the parts and smoothing the joins in German (figs. 77–78).

It is clearly recognizable that the tiger was actually intended as a lioness and only changed into a tiger when it was painted. A group at Lustheim shows the lioness in colours matching the lion.6 As a further variant, the lioness could also appear as a leopard.7 CB

6 Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Meißener Porzellan-Sammlung Stiftung Ernst Schneider in Schloß Lustheim, inv. ES 1999. Illustrated in: Weber 2012, p. 39, fig. 53.

7 Sotheby’s London, 30 April 2015, lot 910.

PEOPLES AND ANIMALS OF FOREIGN LANDS

INTRODUCTION

Vanessa Sigalas

At the beginning of the eighteenth century a fervent fascination with all things considered foreign or “exotic”1 began to sweep across Europe. This enthusiasm extended to Meissen porcelain, where foreign cultures and “exotic” animals became captivating subjects, reflecting the era’s deep fascination with the unfamiliar. Meissen’s porcelain repertoire embraced a diverse array of society, spanning royal and aristocratic portraits, scenes of love and family, and depictions of the working classes, peasants and beggars. Within the animal realm, lions, elephants, camels and monkeys, among others, found themselves immortalized in playful, charming and regal poses. These porcelain creations not only showcased Meissen’s technical prowess but also symbolized the allure of the unknown, blending the mystique of faraway realms with Europe’s refined artistry.

The fervour for East Asia, in particular, manifested itself in various ways. Nourished by both travellers’ accounts and their own creative musings, many Westerners of that era regarded China and other Asian nations as idyllic realms of enchanting tranquillity. These distant lands held a mesmerizing allure, admired by many for their technological advancements as well as their intricate ritualistic societies and profound religions, but were also denoted as “pagan” by others.2 Authentic artefacts brought to Europe through East India companies became cherished treasures, serving as wellsprings of inspiration for European architecture, furniture and decorative arts, including the art of porcelain. A decorative style emerged using motifs and techniques associated with China which was termed “chinoiserie” in the nineteenth century and is still referred to as such today. The scenes depicting people, animals and landscapes in the chinoiserie style, however, did not show the reality of China and its inhabitants, nor was it their intent.3 It was a European fantasy of a faraway region, where not even the geographic location was clearly defined – Chinese, Japanese and other East Asian elements along with Indian and also Persian motifs intermingled with European artistic traditions.4

In Dresden, Augustus the Strong championed the allure of Chinese and Japanese aesthetics. He expanded the Japanese Palace to house his impressive collections of Asian porcelain, setting a trend that culminated in the chinoiserie style’s architectural embodiment at the summer palace in Pillnitz. Simultaneously, he aimed for his porcelain manufactory to surpass imports from East Asia. Following early attempts under Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682–1719) to replicate Asian ceramics, Meissen experienced a significant surge in chinoiserie-style porcelain. Johann Gregorius Höroldt (1696–1775) and his painting workshop spearheaded this wave. While painted chinoiserie designs dominated

< FIG. 84: Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (workshop), Woman from the Bulgarian Coast, 1726–1744. Oil on canvas. 39.5 × 31 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. SK-A-2052. © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

PEOPLES AND ANIMALS OF FOREIGN LANDS

INTRODUCTION

Vanessa Sigalas

At the beginning of the eighteenth century a fervent fascination with all things considered foreign or “exotic”1 began to sweep across Europe. This enthusiasm extended to Meissen porcelain, where foreign cultures and “exotic” animals became captivating subjects, reflecting the era’s deep fascination with the unfamiliar. Meissen’s porcelain repertoire embraced a diverse array of society, spanning royal and aristocratic portraits, scenes of love and family, and depictions of the working classes, peasants and beggars. Within the animal realm, lions, elephants, camels and monkeys, among others, found themselves immortalized in playful, charming and regal poses. These porcelain creations not only showcased Meissen’s technical prowess but also symbolized the allure of the unknown, blending the mystique of faraway realms with Europe’s refined artistry.

The fervour for East Asia, in particular, manifested itself in various ways. Nourished by both travellers’ accounts and their own creative musings, many Westerners of that era regarded China and other Asian nations as idyllic realms of enchanting tranquillity. These distant lands held a mesmerizing allure, admired by many for their technological advancements as well as their intricate ritualistic societies and profound religions, but were also denoted as “pagan” by others.2 Authentic artefacts brought to Europe through East India companies became cherished treasures, serving as wellsprings of inspiration for European architecture, furniture and decorative arts, including the art of porcelain. A decorative style emerged using motifs and techniques associated with China which was termed “chinoiserie” in the nineteenth century and is still referred to as such today. The scenes depicting people, animals and landscapes in the chinoiserie style, however, did not show the reality of China and its inhabitants, nor was it their intent.3 It was a European fantasy of a faraway region, where not even the geographic location was clearly defined – Chinese, Japanese and other East Asian elements along with Indian and also Persian motifs intermingled with European artistic traditions.4

In Dresden, Augustus the Strong championed the allure of Chinese and Japanese aesthetics. He expanded the Japanese Palace to house his impressive collections of Asian porcelain, setting a trend that culminated in the chinoiserie style’s architectural embodiment at the summer palace in Pillnitz. Simultaneously, he aimed for his porcelain manufactory to surpass imports from East Asia. Following early attempts under Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682–1719) to replicate Asian ceramics, Meissen experienced a significant surge in chinoiserie-style porcelain. Johann Gregorius Höroldt (1696–1775) and his painting workshop spearheaded this wave. While painted chinoiserie designs dominated

< FIG. 84: Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (workshop), Woman from the Bulgarian Coast, 1726–1744. Oil on canvas. 39.5 × 31 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. SK-A-2052. © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

91 JAPANESE LADY WITH CHILD AND HERON IN A BOAT

Model most probably by Peter Reinicke, c. 1758

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1758–1760

Crossed swords mark in underglaze blue

Mount: gilded bronze, France, Louis XV period, c. 1760

H. 18.5 cm, W. 20.2 cm (in total); H. 14.5 cm, W. 18.6 cm (porcelain group only)

GRAPHIC SOURCE: Cormorant fishing. Etching and engraving by Gabriel Huquier (1695–1772) after a painting by François Boucher (1703–1770) from the series Scènes de la vie chinoise, c. 1742 (fig. 103)

LITERATURE: Andres-Acevedo 2017, p. 110, no. 25.

FIG. 103: Sheet 301 × 237 mm. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953, inv. 53.600.1019(5) © bpk / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cormorant fishing has a centuries-old tradition in China and Japan and is still practised on a small scale today. From the early seventeenth century, tame, trained cormorants are also documented at the royal courts in England and France. Nevertheless, the bird depicted here is a heron.

The mould number 2466 suggests that the group could well have been created earlier than the other examples of the series. CB

MOUNTED PORCELAIN

INTRODUCTION

Marie-Laure de Rochebrune

While it is certainly the case that many great French eighteenth-century connoisseurs had a high regard for Meissen porcelain, closer examination of contemporary documents reveals that these porcelain-lovers had a special preference for the pieces that had undergone veritable metamorphoses at the instigation of the Parisian marchands-merciers who had imported them to France. And it is a fact that these dealers did not hesitate to modify the appearance of the porcelain pieces and indeed even change their primary function, engaging the best available founders to give them mounts or a terrace-like stand in gilded bronze (“ormolu”), sometimes enhanced with a clock from a Parisian maker and porcelain flowers from the Vincennes manufactory. In doing so, the marchands-merciers acted as creative designers and at the same time as coordinators between the various artisans of whose services they availed themselves.

In eighteenth-century France there was already a long tradition of using metal to enhance porcelain objects, in particular figures or figural groups and vases, which went back as far as medieval times, as is shown by the famous celadon-glaze vase from the collection of ancient objects of the Grand Dauphin, son of Louis XIV, subsequently owned by William Beckford in the nineteenth century and now preserved in Dublin. In the fourteenth century it was given a costly silversmith’s mount that is lost today but clearly visible on a watercolour in the Gaignières Collection. The practice was originally intended to give a more splendid appearance to pieces from China, which at that time were great rarities in Europe and regarded as extremely precious. Earlier still, in the medieval period, the practice had developed of giving silversmith’s mounts to very costly objects such as gemstones. While the first porcelain mounts were crafted in silver, vermeil (silver-gilt) or gold and were often enhanced with enamels, at the end of the seventeenth century these precious metals gave way to the gilded bronze known as ormolu, which had become the particular speciality of the Parisian fondeurs-ciseleurs, who cast the bronzes and finished them with chasing and chiselling. The greatest collectors were won over by the novel material, and the field of porcelain-making benefited greatly from the new obsession. Ormolu now replaced the mounts in precious metal that had adorned Chinese and Japanese porcelain, as saliently demonstrated by the mounts of the Japanese porcelain vases that belonged to the prince de Condé and are now preserved at the Louvre (fig. 135).

Gilded bronze was one of the greatest successes in the entire field of Parisian artisanry and as such very soon conquered all Europe.1 Although the technique had medieval origins, it had fallen into obsolescence. When it reappeared at the end of the seventeenth century, it first made its presence felt in interior design, notably in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, where Pierre Ladoireau designed some remarkable ormolu trophies in 1682. It

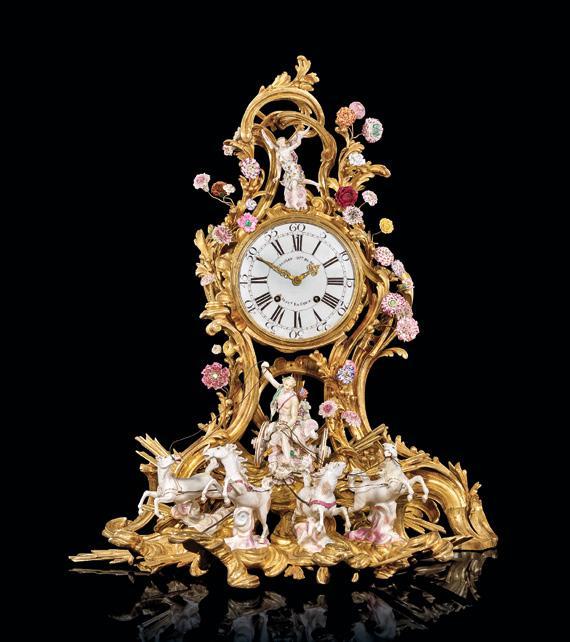

< FIG. 134: Clock with Apollo’s chariot. Meissen porcelain: models by Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1750; clock: Edme Jean Causard (1718–1780), Paris, c. 1750; gilded bronze mounts: Paris, c. 1750; flowers: Vincennes porcelain. H. 98 cm, W. 82 cm, D. 56.5 cm. Christie’s London, 6 July 2023, lot 45. © Christie’s Images 2023

< PAGE 356

133 ELEPHANT AND SULTAN, MOUNTED AS A MANTEL CLOCK

Porcelain: Model by Peter Reinicke, c. 1749

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1749–1750

No visible mark

Mounts: gilded bronze, France, Louis XV period, c. 1750

Flowers: soft-paste porcelain, France, mid-18th century

Dial plate signed “ETIENNE LENOIR A PARIS” (Étienne Lenoir, 1699–1778, master in 1717, or Pierre-Étienne Lenoir, born 1724, master in 1743)

Clockwork signed “Et. Le Noir A Paris” H. 46 cm, W. 33.5 cm

LITERATURE: Den Blaauwen 2000, pp. 411–412, no. 300. Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, pp. 366–367, no. 107. Exh. cat. Chantilly 2020, p. 234, no. 92.

A sultan riding an elephant mounted with a round clock. The elephant stands on a voluted ormolu base decorated with rosettes. The sultan wearing a jewelled turban and seated on a saddle crowning the clock. The elephant-driver or “mahout” sitting on the animal’s neck. DG

This specimen is a further version of the group discussed under cat. 79, which has been extended with a clock and porcelain flowers from Vincennes. The sultan is now enthroned on top of the clock. Étienne Lenoir and his son Pierre-Étienne worked together as clockmakers from 1750 to 1771. They both used the signature “Étienne Lenoir”, which makes it difficult to distinguish between their works. Their clients included the art dealer Lazare Duvaux (c. 1703–1758), as well as the Marquise de Pompadour (1721–1764) and the Countess du Barry (1743–1793). CB

branches decorated with many different flowers. A large clock carried by the tree forms the visual centrepiece.

The rider can be recognized as a Turk by his turban, baggy trousers and bushy moustache. He is leaning against a cushion roll decorated with a tassel. The colourful patterned tunic falling down over his yellow trousers is fully buttoned. An open turquoise-coloured robe completes his attire. The shoes are coloured red.

For the rhinoceros, see cat. 80.

The lightness of the ensemble is captivating. The clock seems to float amidst the delicate branches, and the Turk sits so casually on the animal that it is hard to imagine him as a rider. But according to the mould number 1692, the rhinoceros and the Turk were probably made together, around 1752. CB

135 PARAKEET AND PARROT, MOUNTED AS A MANTEL CLOCK

Porcelain: Models by Johann Joachim Kaendler, 1740 and 1741

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1740/41–1743

No visible marks

Mounts: gilded bronze, France, Louis XV period, c. 1750

Flowers: soft-paste porcelain, France, mid-18th century

Dial plate signed “MUSSON A PARIS” (Pierre Musson, 1711–1780, master in 1746)

H. 61 cm, W. 43 cm (overall); H. 18.6 cm (parrot); H. 29.5 cm (parakeet)

WRITTEN SOURCES: Work reports of Kaendler, May and June 1740 (parrot), June 1741 (parakeet) (Pietsch 2002, pp. 70 and 80)

The parrot ordered by the Parisian merchant Jean-Charles Huet (d. 1755)

The parakeet ordered by Frederika Alexandrine Moszyńska (1709–1784), daughter of Augustus the Strong and Countess Cosel

LITERATURE: Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, pp. 374–375, no. 109.

Exh. cat. Chantilly 2020, pp. 232–233, no. 91.

134 RHINOCEROS AND TURK, MOUNTED AS A MANTEL CLOCK

Porcelain: Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1752

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1752–1755

No visible mark

Mounts: gilded bronze, France, Louis XV period, c. 1755

Flowers: soft-paste porcelain, France, mid-18th century Dial plate signed “Gille L’Ainé A PARIS” (Pierre François Gille the Elder, c. 1690–1765, master in 1746)

H. 55.7 cm, W. 37 cm

LITERATURE: Andres-Acevedo / Bodinek / Reyes 2020, pp. 369–373, no. 108.

Exh. cat. Chantilly 2020, p. 235, no. 93.

On an ormolu base, a rhinoceros stands looking to the left with a figure on a cushion as its rider. A tree rises behind the animal, its

Andres-Acevedo 2023, p. 95, no. 212 (parrot), and pp. 110–111, no. 273 (parakeet)

On an ormolu base two Meissen porcelain birds perched on tree stumps, a rose-ringed parakeet (to the left) and a green Amazon parrot (to the right), naturalistically modelled and coloured in shades of green, purple and blue. The parakeet is holding a piece of sugar in its left claw, at which it is pecking. A few cherries are hanging from its tree stump. Between the two birds rises a gilded bronze shrub, bearing the clock and adorned with numerous flowers. DG

144 PAIR OF SWANS, MOUNTED

Porcelain: Models by Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1750

Manufacture and decoration: Meissen, c. 1750

No visible marks

Mounts: gilded bronze, France, Louis XV period, c. 1750

H. 17.6 cm and 18.5 cm (with mounts)

LITERATURE: Andres-Acevedo 2017, pp. 280–281, no. 92.

Two swans, facing each other, each sitting on a curved piece of grass resting on a raised ormolu plinth, from which water seems to run. Tall reeds in the background. CB