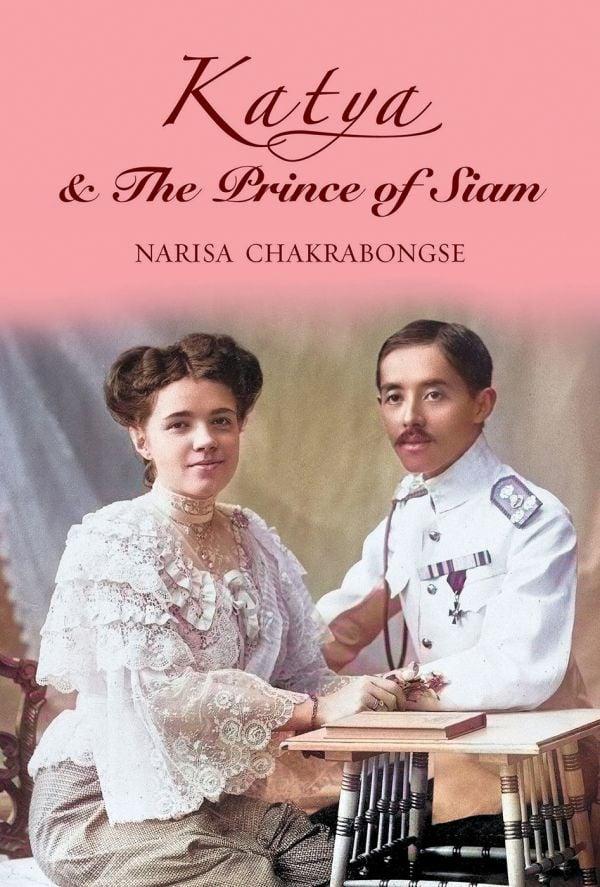

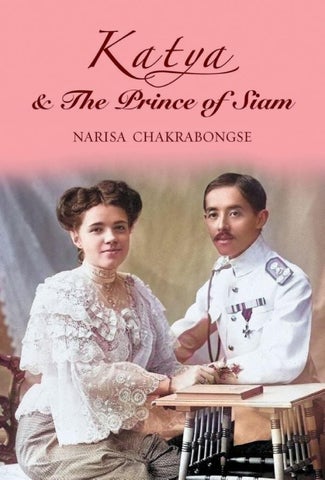

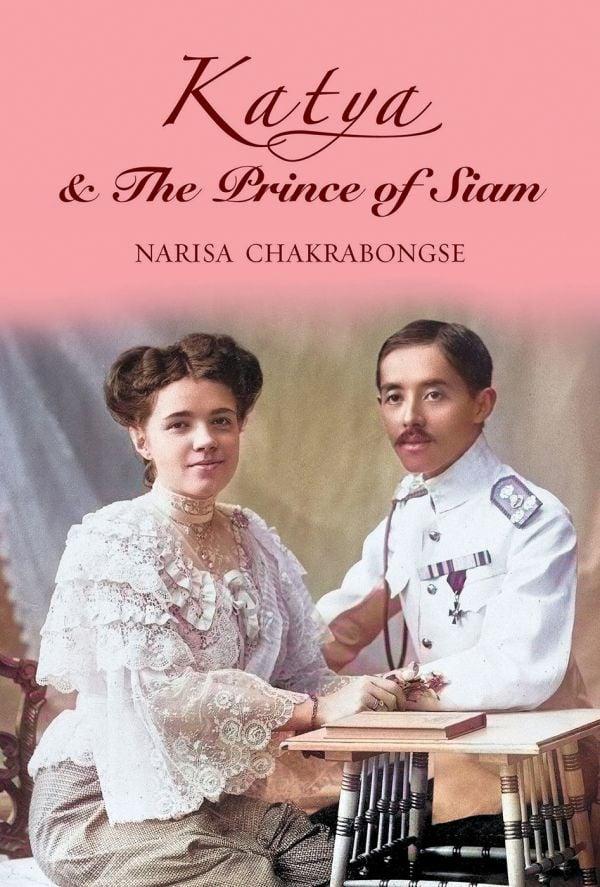

The story of Katya – Ekaterina Ivanovna Desnitsky’s marriage to Prince Chakrabongse of Siam – had intrigued me since I was a teenager. After my mother died, I talked about it with my aunt, Eileen, and we decided to write a book based on the many letters and diaries left to me by my parents. Eileen had heard of it in 1938, the year that Prince Chakrabongse and Katya’s only child, Prince Chula, married her sister Lisba Hunter. Although there was considerable opposition to their marriage from the family, it was nothing compared to the anger of the Siamese royal family when, in 1906, Chakrabongse, a favoured son of the reigning monarch, chose a ‘farang’ – a foreigner – as his bride.

The Chakri Dynasty, rulers of Siam since 1782, had then a strict tradition of consanguineous marriage among royalty ‘to maintain the purity of the stock’, and was shaken to the core, not so much by the fact that Katya was a commoner and an orphan without fortune, but because she was foreign. In the words of one of Chakrabongse’s full brothers, Prince Prajadhipok, ‘The marriage was a national dynastic catastrophe!’

To fully comprehend the intensity of this reaction on the part of his family, it is imperative to touch briefly on the background into which Chakrabongse was born in 1883. Although his father, King Chulalongkorn (r.1868-1910), was said to have had 92 wives and 77 children, his favourite wife was Queen Saovabha (1864-1919), and Chakrabongse, one of her nine children, was one of his favourite sons. He was also the grandson of King Mongkut (r.1851-1868), and the character and remarkable changes brought about in Siam by both his father and grandfather were to profoundly affect his own short life.

Mongkut, well known in the West through Anna Leonowens’ book, An English Governess at the Siamese Court, and the loosely derived musical, The King and I, was in every respect a different character from his portrayal in both. He was born in 1804, the son of King Rama II, and when he was twenty – as was customary for Siamese princes – he entered the priesthood for what was generally a short period of about three months. But in his case, this ‘short period’ was prolonged into a sojourn of 27 years, for hardly had he stepped inside the monastery doors, when the king, his father, died without having named an heir.

1905 was a year of great turmoil with what is often referred to as the first Russian revolution beginning on 22nd January when peaceful demonstrators were massacred in St. Petersburg. Discontent with the disastrous Russo-Japanese war, workers’ strikes over pay and conditions and student protests transformed the capital city into a dangerous place. Katya’s brother, Vanya, was unable to attend his classes at St. Petersburg University, while she, already volunteering as a nurse at the Fontanka hospital under the patronage of Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, decided to travel to Lake Baikal where wounded soldiers from the Russo-Japanese war were brought via the Trans-Siberian railway to be nursed at hospitals around Irkutsk. The hospital where Katya was based was at Slyudyanka situated at the tip of Lake Baikal. The settlement grew up from 1905 onwards due to its location at the junction between the Trans-Siberian and the Circum-Baikal railway.

When I first started research about my grandmother, it was not clear why she decided to become a nurse. Since that time, new information has come to light. Thus in 1907, writing to Vanya and reflecting on the past, Katya recalled an unhappy love affair:

‘With Igor I suffered a lot. I loved him with all my soul, and it’s because of him that I became a nurse and went to [war]. I went through a lot, not physically, but emotionally. . . I survived and came back. Igor had stopped writing to me for a long time, I spent my last money for telegrams and didn’t receive an answer. I often felt desperate. . .’

Judging from her descriptions, the living conditions at Slyudyanka were spartan and the work was uncomfortable and hard. While she was there she wrote a few letters to Vanya. From one of them it seems that Katya’s uncles and aunts did not approve of her decision to become a nurse. She was still only 19 years old. However, the months she spent nursing the sick gave her great satisfaction. Writing to Vanya she said:

‘ I am infinitely glad, my dear, that despite all the condemnation and censure, I nevertheless came here. My health is excellent, my state of mind is calm, and this is the most important thing. I have a huge request for you, if there are no riots, be sure to go to Petersburg and finish the university without fail. If you don’t do this, then you will upset me very much. . . I left Petersburg with a very heavy heart. All the nurses were seen off by their relatives, but only Aunt Sonya saw me off. It was very sad to go so far away and realize that your relatives are completely indifferent.’

In fact, Prince Chakrabongse and Poum were among the small group who saw her off. The trip from Petersburg passed without incident even though ‘on the road, it was really necessary to be careful as we had a lot of soldiers with us. I talked with them, as did all the sisters, but as soon as there was an undesirable tone we went into our cabins.’

The nurses were referred to as ‘sisters’ and were part of the Red Cross under the auspices of the Kaufmann organisation established in 1900. Katya was fortunate to begin her nursing career in the Siberian spring and summer, so that when not performing their duties, she and her fellow nurses could enjoy the surrounding countryside, the beautiful scenery and boating on the lake, as well as going into the forest with recovering patients to collect strawberries and currants. ‘It is necessary to go with guns, as you can stumble upon a bear or a wild boar. Today we are going as a group with provisions and we will cook and eat there together with patients from other barracks. We invent all kinds of entertainment for ourselves and the sick and therefore the soldiers are very fond of our infirmary.’

‘Whoever visits Siberia and Transbaikalia will not want to go abroad; such is the beauty here. I would love to live here. Now it is pouring with rain, the mountains are not visible, they are covered with clouds, Baikal roars and rages, but we still put on our oilcloth mackintoshs and go to the Pass, the biggest mountain. After all, our boots are waterproof and come above the knees.’

In the evenings there was often singing. ‘There is a Malorussian [ie Ukrainian] woman from Poltava province here; we get along very well and we live in the same room. Everything she has is covered with plakhtas [a traditional Ukrainian wraparound skirt]. I am so pleased with this, for some reason, I remember our life in Boyarka [a suburb

Katya in her uniform.

Katya with the small dog she was given at Sludyanka.

southwest of Kyiv], and she reminds me of our mother, since her clothes always included a plakhta. In the evenings, we gather in our room, and the singing begins to the accompaniment of the zither. One sister sings wonderfully and also plays the zither – very often a Malorussian song. ’

In this pre-revolutionary period, Malorussian was the word generally used to refer to Ukraine. A separatist movement existed from the 19th century. The territory was briefly independent after 1917 before becoming designated as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Katya was proud of her work and told Vanya that an inspection by a highup medical officer led to an assurance that this was ‘the best infirmary in Transbaikalia.’ But some of the cases were tough. One of the patients on her ward was a convict who had been sent to Sakhalin, allegedly for smuggling, but Katya suspects for something worse. Another had had a nervous breakdown after apparently causing a dangerous train crash. ‘He shakes all the time and starts at every noise, and is afraid of the locomotive. There is little hope for recovery. And now he is sure that he is at the same station and that a locomotive will crush him. He is only 24 years old. This patient has made a terrible impact on me.’ On another occasion, she went on a train where everyone was mentally unstable, presumably as a result of post traumatic stress. However, she cautions Vanya against joining her. ‘What I can endure, you would hardly be able to. I have been a

In late March 1907, King Chulalongkorn began a seven-month trip to Europe in order to reinforce the diplomatic relations established during his first trip 10 years earlier and to seek the advice of doctors about his worsening kidney condition. In his absence, Crown Prince Vajiravundh was appointed as regent.

King Chulalongkorn returned from Europe on 17th November 1907. Perhaps Chakrabongse thought his father might now come round to meeting his wife but, throughout this time, although Chulalongkorn was duly informed of the altogether favourable impression made by Katya on the queen and other members of his family and, though he must have been struck by the less rigid ambience of the English royal court, there was no change in his attitude towards his daughter-in-law. Later, it is true, he would sometimes ask after her, express pleasure in hearing she admired the layout of Bangkok, for which he was responsible, and remark that he was interested that she shared his hobby of breeding Leghorn chickens. Otherwise, to the end of his days, he remained firm in his resolve neither to meet her nor acknowledge her publicly.

It is probably true that if Chakrabongse had begged to be forgiven for his marriage, his father’s attitude might have been different, but he was a proud young man and never brought himself to do so. In the course of one particular discussion, the king reminded him that when marrying he should have remembered that he was second in the line of succession, and that when he enquired what titles he would expect a possible son to have, Chakrabongse had replied that plain Mister would do.

This petulant remark ceased to be of mere academic interest on Saturday, 28th March 1908, for at 11.58 p.m. on that day, Katya gave birth to a son. The exact hour of this event is known as Prince Chakrabongse hoped fervently that his child would come into the world on a Saturday, as both he and the Crown Prince had done. Watch in hand, he was delighted when the infant obliged him – if only by two minutes! On 29th March Chakrabongse wrote to his father to tell him of the birth of his son. Although that letter is lost, the king’s immediate reply included the following sentences:

Reception committees and guards of honour were on hand at all the various stops made by the train on the way to St. Petersburg, where they arrived on 4th June to be installed in the Europa Hotel, just off Nevsky Prospekt and at that time the finest hotel in the city. The rooms were large and spacious with much walnut panelling, mirrors and even marquetry pianos in the best rooms.

The excitement they must have felt at being back in the city where they had met and fallen in love is not recorded as Chakrabongse was partly writing his diary so it could be used later for reporting back to the king and the army. Nevertheless, the timing of their visit was most opportune as June in St. Petersburg is the time of the famous White Nights when dusk does not come till two o’clock in the morning and the Nevsky Prospekt and banks of the river are thronged with strolling couples into the early hours.

Next day they were up early to devote the morning to the prince’s wardrobe – a Russian tailor measured him for a new white general’s tunic, followed by an English tailor charged with equipping him with English court dress: black satin knee-breeches and silk stockings for the coronation. Later a cobbler attended to take instructions for making buckled shoes. These vital sartorial matters dealt with, after luncheon he and Katya visited Colonel Deguy, who was in hospital, and they ‘discussed certain matters in full’. Perhaps Poum was the subject of this talk as he had been advised to quit St. Petersburg during Chakrabongse’s visit as a result of his refusal to return to Siam in 1906 when commanded by King Chulalongkorn, and thereby having become ‘persona non grata’ with the Siamese royal family. Apparently, Poum’s regimental commander had asked him to stay away but one imagines that, Chakrabongse and Katya would have had some news of him from Madame Khrapovitzkaya, to whom Poum remained devotedly attached.

In late afternoon, Chakrabongse was delighted by his visit to the Siamese embassy for ‘all was exactly the same – even every chair and table in the same place as I remembered it, and my bedroom also completely unaltered.’

On 6th June, wearing ‘full dress summer uniform – grey tunic, holster belt and sash’, Chakrabongse left by special train accompanied by the head of the Protocol Department to call on the emperor at Tsarskoye Selo. After a short forty-minute trip, he arrived at the pretty cream-painted station to be greeted by Grand Duke Cyril and

Chakrabongse and Katya outside the Siamese embassy in St. Petersburg together with his aide-de-camp Prince Amoradat Kridakara (Ta Pong).

a guard of honour, together with some old friends, with whom he had been in the Hussars. After inspecting the guard and presenting his own suite, the whole company bowled off in open carriages to the Alexandrovsky Palace, which he writes ‘was surrounded by flowerbeds, some filled with wallflowers, which not only looked beautiful but smelled wonderful.’

At the palace, he was received by dignitaries of the Imperial Household, then a page conducted him to a reception room adjoining the tsar’s audience chamber where, shortly afterwards, he was shown into the imperial presence. The emperor was ‘wearing Hussar uniform and the Chakri sash and chain. He received me most warmly and showed he was really pleased to see me again.’ The tsar talked of the long journey from Siam to Russia, and enquired after King Vajiravudh and the queen mother before saying how much he regretted the death of his old friend Chulalongkorn. He also asked after Katya and, as there is something sad and almost cruel in the manner in which a morganatic wife is generally completely ignored by royal personages, this pleased Chakrabongse immensely.

After Chakrabongse had presented the emperor with a richly chased gold and enamel box which was received with every mark of pleasure, they returned to the reception room where tables were set out with an enticing assortment of zakuski before luncheon was served, and twenty-six guests sat down at a long table glittering with silver and a profusion of pale pink roses; Chakrabongse sitting on the right of his host and next to Prince Dolgorukov.

Other letters kept Katya abreast of various dramas involving the large and complex royal family. An interesting passage was critical of an article on women written by King Rama VI under his nom-deplume of Ramachitti. Enclosing the article, Chakrabongse commented

‘ You will see that there is almost nothing new, I have personally spoken about all this a hundred times and I really want to ask Ramachitti why he wrote to the newspapers, why not do something himself to prove his words. For example, during festivities at court, why don’t women sit with men? It completely depends on him, it is also up to him to stop polygamy, so why just write about it? ’

By June, Katya was in Japan and wondering whether to go to America or not. Her mood was still unhappy, her only consolation some shopping:

‘To be honest, I am sick to death of Japan because everywhere is the same. All the shops have the same items. There are two types of Japanese – either over polite or quite the opposite and rude. . . It’s quite clear that they hate Europeans but are always ready to sell them something.

When I feel lonely, I like to wander around the shops. Sometimes I don’t buy anything but it makes me feel better. I am a woman after all. In the embassy I saw a clever thing for

catching flies so of course I asked Phya Chamnong to buy three for Hua Hin and at home. You know I am good at housekeeping and decorating. Don’t tell me off, my dearest. At the moment I am being very cautious not like when I was in Europe in 1913. I am only buying things that are needed for Bangkok and have only had a few outfits made. I spent in China and paid a lot for the hotels. I still have £500 and 2,500 yen.

Don’t be cross with your wife for being extravagant. Phraya Visan says I am staying in too much and that is why I am only getting better slowly. He thinks I need friends to cheer me up but I don’t think that will help. When I feel well I am happy to be just with Healey and Chaem. But when I am unwell, I don’t want to see anyone. I know these types of friends – they stay up late and drink but that won’t make me better. If I am patient and stay quiet, my health will improve.

Bira and his portrait of Chula, with Charles Wheeler.

Bira was most engaging and talented, retaining for much of his life a childlike air of innocence and egoism – the more disarming because it was so natural. He was slight but athletic with restless way of seldom standing still but shifting rapidly from one foot to the other. Many of his most prized possessions were toys including a vast model railway, in which he could remain absorbed for hours on end. He also had amazingly nimble fingers and, at one point, used to fashion exact replicas of different types of aircraft, tiny enough to fit into a matchbox. During 1933, he and Chula moved into a flat in Kensington, and as Chula – unlike most of his royal relatives in whom it amounted almost to a passion – actually disliked shopping, Bira was entrusted with buying the furnishings. Unsurprisingly, his taste was in tune with the times: square deep armchairs, plenty of chromium-plate and sombre or neutral colours.

After much discussion, Bira eventually decided that an academic career was not for him, and abandoned the plan of going to Cambridge in favour of studying sculpture. After an initial trial period, he was accepted as a pupil by Charles Wheeler RA (1892-1974) In 1934 when Wheeler became an Associate of the Royal Academy, he was considered a bit of a rebel but he later became President. Under his tutelage, Bira made excellent progress, later exhibiting at the Royal Academy himself. Meanwhile, Chula worked hard at his literary work, having two more biographies published in Siam, as well as being an avid theatre

Chula in the Riley Imp.

goer and attending performances by the Ballet Russe. Despite such an active social life, neither of them neglected their mutual great interest in motor cars and motor racing. In 1935, Bira ran in some short handicap races at Brooklands, driving a Riley Imp, painted hyacinth blue – Katya’s favourite colour – which soon became known as ‘Bira Blue’. The Riley was superseded by a super-charged MG Magnette, but after watching the performance of cars built by a small firm based in Bourne Lincolnshire, English Racing Automobiles, which became widely known as ERA, Chula, considering their productions were the best of the light car class, purchased one for Bira and presented it to him on his twenty-first birthday.

By now, Chula had decided to go in seriously for racing and to act as Bira’s manager. That the two of them, together with the first-rate technicians they assembled, made a wonderful team is part of motor racing history. When, in his first race in the new car at Dieppe on 20th July 1935, Bira came in second, Chula realised that the White Mouse team (so-called after Chula’s Thai nickname Nou meaning mouse) could be a serious contender in light car racing.

Chula had clearly inherited, along with his father’s industry, his talent for organisation. This was obviously recognised by the racing correspondent of The Times who, when Bira won the International Trophy at Brooklands in May 1939, wrote: ‘Bira’s success was as well-deserved as his frequent victories always are. As a driver he

An invitation to Prince Chula

The Munich Agreement, engineered by the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, in September 1938, was judged by some in Cabinet and Parliament, and by many ordinary people in Britain, to be not only shameful but ineffective: merely a temporary halt on the march of events towards inevitable war. On the other hand, there were those who welcomed it with joy and thanksgiving and believed Chamberlain when he hailed it as ‘peace with honour’ and ‘peace in our time’

In the year-long respite that followed, a minor effect of the still existing uneasiness – a feeling of waiting for catastrophe – was the number of couples who hurried to advance the date of their marriage. This was the case with Lisba and Chula, whose wedding took place on 30th September instead of October, as they had at first intended. Their attachment had survived much guarded or straightforward disapproval on both sides. Chula’s uncle, King Prajadhipok, had in the past begged him more than once not to follow his father’s example and marry a ‘farang’ and such a union was automatically frowned on by all his royal relatives, while the few among his many English friends to whom he made known his matrimonial intentions were dubious or cautiously lukewarm at best.

Lisba’s parents were deeply concerned and troubled, faced with a prospect they could never have envisaged for one of their four daughters. They had also, of course, to face the pain of separation, for they imagined that Lisba inevitably would spend much of her future life in a country and among people of whom they knew next to nothing. My grandfather, in particular, felt unhappy and bereft, for he was especially fond of Lisba. Only Eileen, convinced that theirs was an enduring love, gave them her unreserved support. Other relations, unanimously ‘shocked’ and ‘dismayed’, wrote letters of ‘condolence’ instead of congratulation, telephoned their ‘sympathy’, and in one case called round in person to enquire if Chula was really black. Today, almost 90 years later, now that prejudice against mixed marriages has greatly weakened, these attitudes seem strangely narrow minded, but then it made for a fraught and trying situation, which was only relieved when the wedding took place and became an accomplished fact. However, although Lisba’s father remained

The four Hunter sisters, from left to right, Clare, Lisba, Eileen and Janie.

cordial and composed at the registry office and the Siamese Legation afterwards, he cut a lonely figure as he wandered away on his own to hide his feelings.

Katya and Hin were not among the family and few close friends who were present, and Chula explained in one of his books that, ‘My Mother did not come over from Paris due to the tenseness of the political situation as we expected war to be declared at any moment.’ Nevertheless, her absence seems strange. Perhaps Katya, now plain Mrs Stone, may have been unwilling to witness Lisba become Princess Chula, as she had become Mom Katerin so long ago. Notably absent too, despite living in England, was King Prajadhipok. After a brief honeymoon in the West Country, Lisba and Chula returned to the London flat. Then, in October, taking advantage of the still prevailing though uneasy peace, together with Bira, Ceril and Abhas, they sailed to Siam where they stayed until March 1939, before attending a few more motor racing events. Three months after their return, in June, the country’s name was changed to Thailand. They were well received in Bangkok and the trip was also important for Poum, who was visiting his homeland for the first time in almost 40 years.

* * *

After the false promise of the Munich Agreement, the outbreak of war on 3rd September 1939 brought customary life to a standstill. As Thailand had declared her neutrality, Chula at first thought of returning to Bangkok but sailings were difficult and, even when arranged, liable

Lisba and Prince Chula looking rather anxious on their arrival at Hua Lampong Station, 1938.

to postponement or cancellation. Having booked passages on at least three vessels, one of which was subsequently torpedoed and packing and unpacking three or four times, he decided to stay in England. He predicted presciently that London and the Southeast of England would be bombed by the Germans and asked Lisba and her sister Eileen to go to Devon and Cornwall to find a property to rent.

After many misadventures inspecting numerous dirty, dilapidated places with broken furniture and grimy kitchens, or vast dank mansions unheated but for rickety oilstoves, the sisters were about to give up when they spotted ‘Lynham Farm, Rock, a charming modernised farmhouse, with a small, well-established garden and tennis-court, overlooking a beautiful estuary’. Driving down with trepidation, Lisba found the house indeed delightful: low-ceilinged, thick-walled, furnished with great taste, fresh chintzes and pale unemphatic wallpaper and paint; it was also roomy enough to contain a considerable household. Once all the business details had been settled, a cavalcade left London consisting of Chula and Lisba, Bira and Ceril, Shura Rahm (who had been an active member of the motor racing ‘equipe’ ), Chula’s Thai clerk Bian, a manservant, a cook, two racing cars, two dogs and Josiah, a remarkable bird – a Malaysian Grackle, black with a white waistcoat, who would puff out his chest and bow in stately fashion.

The arrival of a Royal Highness with such an entourage caused no little stir in the village and, for weeks after they had settled in, the local house agents with the euphonious name of Button, Menhennit & Mutton, displayed a small handwritten notice in their window reading: ‘Lynham Farm, let to HRH Prince Chula of Thailand by us.’

I come late to Katya’s story. My father had not been keen to have children. Although he didn’t speak publicly about his childhood, some private letters reveal how he suffered as a result of his mixed heritage and the endless discussions of his position and role in the Thai royal family. I don’t know when they decided to have a child, but I was born on 2nd August 1956 after they had been married for 18 years. As a result, I never got to know Katya as she died three and a half years later in Paris, while we lived in Cornwall. Nor did I know my Thai grandfather as he died almost forty years before I was born. Then after Katya’s death, my father only lived for another four years, meaning I did not know him well either. He was cremated in Truro and we brought his ashes back to Bangkok for funeral ceremonies. The seven years that we were together, he was a rather remote figure. I had a nanny, Dorothy Thomas, known as Nin Nin, whom I loved very much, and I spent a lot of time in the nursery up in the top of our house in Cornwall, or in Thailand in my room with a huge mosquito net weighted down by chains.

After his death, my mother and I continued living in Tredethy and coming to Bangkok once a year where I went to Chitralada School in the grounds of the royal palace for one term a year. In this way, my mother honoured my father’s request that I should be able to read and write as well as speak Thai. The school had been established so that the four children of King Rama IX could go to a regular school and have a semi-normal childhood. For me going for only a term and being the only white-looking pupil was difficult.

Eight years later in 1971, my mother died and my world fell apart. At that time, I was all alone with no grandparents, no parents, no brothers or sisters. I went to live with an aunt, who was going through a difficult period in her life, and I was very unhappy.

Narisa, Lisba and Chula, 1957, together with Pompey the poodle.

After my mother’s death, I had to sort out a mountain of furniture, paintings, china and papers from our house in Cornwall. My father had been a bit of a hoarder and my mother had not dealt with his things. Not only were there valuable items, but trunks of scrapbooks, theatre programmes, 78 long-play records and clothes. I was too young to deal with everything properly, but somehow I organised for the portraits, chinaware, letters and diaries (these latter later used to write Katya and the Prince of Siam) to be sent back to Thailand. I was finishing my schooling and going to university over this period and my memories of that time are quite hazy.

Later, in 1991, a collection of letters between Prince Chakrabongse and King Chulalongkorn, probably stolen from my house in Cornwall at some point, came up for auction at Christies and after quite a tussle I managed to acquire these and add them to the archive. In 2017, I had finished translating all of these letters and published Letters from St. Petersburg. I have been able to correct some dates and add some new material to this book as a result of that work.

* * *

The first edition of Katya and the Prince of Siam was translated into Russian by a cousin on Katya’s father’s side, Maria Desnitskaya. In 1990, I had been working on the book and went to St. Petersburg with my stepdaughter, Juliette. For some reason, there was a small article about me in the Petersburg newspaper and the guide I had been assigned who worked at the university said ‘I think a cousin of yours is studying at the University.’ We met and also went to see an exhibition of her mother’s work, Alexandra Desnitskaya, a Russian National artist.