Trentino-Alto

Friuli-Venezia

Emilia-Romagna

Trentino-Alto

Friuli-Venezia

Emilia-Romagna

Why did I decide to venture out on this odyssey? Because I’m curious by nature. Because I wanted to draw up a map of culinary Italy. Because I wanted to venture off the beaten path, taste all those amazing products, and immerse myself in their wondrous world and the stories behind them. Italia con gusto e amore is an account of my travels through twenty regions and encounters with people obsessed by their culinary heritage. Over the course of seven months, I travelled 23,000 kilometres in search of authentic, underappreciated local fare that you find on the streets and in homes around the country. Along the way, I recorded the countless stories of passionate Italians whose lives revolve around honest, delicious food!

Breathtaking coastlines, sun-drenched countryside, UNESCO World Heritage sites and cities serve as a stunning backdrop for my encounters. What a country! I was blown away by the rich mosaic of remote hillside towns, winding mountain roads, castles, cliffs, seas, and beaches. A different landscape awaited me every hundred kilometres. The journey from region to region was a joy in itself. The soil, the climate and the people changed, as did the panoramic views. Italy really does have it all! Or almost, because the Italians themselves think their politicians are corrupt, their democracy is vulnerable, and their economy and football team is constantly yo-yoing... But their cuisine is first-rate, and nothing can change that!

There is no other place in the world where food gets taken this seriously. The Italians elevate food and drink to an art form; they are masters at creating irresistible gourmet feasts. Whether it’s in family circles, in the local village or town, or during a celebration; there is always an occasion for enjoying traditional cuisine. What used to be considered cucina povera, or peasant cooking, is now a celebrated form of cultural heritage. The street food delicacies I sampled taught me much about a city or region’s character and history. The recipes and the craftsmanship have been preserved and handed down from generation to generation. ‘Con gusto e tanto amore!’ or ‘with flavour and lots of love!’, the many heroes and heroines I met along the way would say with conviction.

Each region has its own history. Italian cuisine has been influenced by the many cultures that have passed through or ruled the regions over the centuries. The Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Byzantines, and Spaniards are only a few of the many cultures that contributed to a gastronomy that has held fast for centuries. Italy as a country didn’t exist until the second half of the nineteenth century. Before unification, Italy was one giant puppet show of city-states, constantly at each other’s throats. This diver-

From Teramo, I drive 65 km to the city of Pescara. The city is located where the Pescara River meets the Adriatic Sea. Pescara’s history is marked by plenty of fighting, and much of the city was destroyed during the Second World War. Pescara is now a seaside resort and popular tourist destination. The unbroken expanse of its fine, sandy beaches extends for over 20 kilometres along the coastline.

Along the road that runs parallel to the beach, I meet Alessandro Zaccharo at a roadside stand named Cuccitella. His food truck is located close to the fish market, or mercato ittico, but I haven’t come to see him about fish. It’s mutton I’m interested in. Because throughout Abruzzo, arrosticini is the one dish that you should serve when you have guests coming to visit. It’s the embodiment of Abruzzo’s heritage that you encounter everywhere, from the mountains to the seaside.

This mutton on a stick owes its origins to two provinces: Pescara and Teramo. It is believed that the shepherds who migrated between the mountains and the valleys invented arrosticini. Today, you will find arrosticini being served throughout the region, including in the provinces of Chieti and L’Aquila. Traditionally, only mutton from castrated rams, or wethers, was used for arrosticini. Wethers were only used for wool, and those castrati that died along the way were eaten, for both

practical reasons and to keep the hunger at bay during the long journey. The mutton was chopped up into tiny pieces and skewered on a stick. What makes arrosticini Abruzzese unique is that in addition to the meat, pieces of fat are also put onto the skewers. And it’s that fat which gives this dish the special, unique flavour that has become famous across the globe.

For Alessandro, there is only one possible method for preparing arrosticini: on the barbecue. ‘Solo sulla fornacella!’ or only on the barbecue. ‘Preparing this in a pan is just wrong. That’s like drinking expensive wine from a paper cup,’ he says sharply.

We’re standing next to a long, narrow barbecue. He shows me how he sears the meat over the glowing embers of charcoal and wood. The crackling of fat on the embers and the smell of cooking meat makes my mouth water in anticipation. He turns the skewers once more. The meat is now a lovely golden brown. Alessandro tells me that you don’t add salt until the very end as he liberally salts the meat on the skewers.

‘Arrosticini are served like a bouquet of flowers,’ he continues. ‘They should strictly be eaten with your hands, pulling the meat from the skewer with your teeth. In Abruzzo, this is the only way to serve them, as arrosticini bouquets wrapped in a sheet of paper or placed in special containers in the centre of the table.

From Agnone, I drive 50 km south to Isernia, capital of the province of the same name. I pass green hills as I leave the National Park behind me. The route is breathtaking. In terms of population, Isernia is the third-largest town in Molise, after Campobasso and Termoli. The historical centre is a collection of beautiful buildings, including various churches and opulent palaces, the town hall and the thirteenth-century Fontana Fraterna, built to commemorate Pope Celestine V.

But, I’m not stopping in the city centre. I drive on into the modern part of town to find Garage Street Food, owned by Mattia Rotolo and Gianluca Cortese Tempesta. I wanted to discover how contemporary food concepts could flourish in conventional, traditional Molise.

‘It’s very simple,’ Mattia explains. ‘We make hamburgers based on local, traditional ingredients. We only use the finest quality products from our rich local surroundings: hamburger from Isernia, bread from Montaquila, mozzarella from Bojano, mushrooms and truffles from Cantalupo, vegetables from local farmers and beers from Filignano. The burgers take you on an authentic gastronomic journey through Molise. It’s also turned out to be a huge success!’

As I look at the menu, the first thing that springs to mind is that some burgers are made from scottona Mattia: ‘This is very lean meat from a young animal. A scottona burger’s tenderness is unsurpassed. Scottona is not the name of the actual meat. A ‘scottona’ is a female cow, from 18 to 24 months old, that has never given birth and is destined for the slaughter. You will find their meat at supermarkets and butchers under the supercarni, or top-quality meat’ section. You recognise the meat from the thin lines of fat running through the muscle tissue, like tiny veins. This fat melts during cooking, giving the meat its tenderness and intense flavour,’ Mattia explains.

‘A tartufo hamburger is a must on the menu in this truffle-rich region,’ Mattia continues. ‘Sandwiched between the bread, you will find black-truffle carpaccio, caciocavallo cheese, local porcini mushrooms, a scottona burger, and a fried egg. Whenever we use vegetables such as onions, lettuce, courgette, and tomatoes, they must be locally produced. Did you know that each year, we hold a celebration in Isernia to honour the products that come from the soil? Our cuisine is rich in vegetables. On the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, this old city is transformed into a picturesque paradise. This feast is very ancient, and it’s generally believed that the onions bought during the feast have strong medicinal qualities.’ He winks when he says this last part, I suspect to help me draw my own conclusions about whether I should believe it.

Having this conversation in a burger bar with young men dressed in the style of American bikers as mopeds race past with deliveries feels surreal. They have taken the region’s culinary riches to heart and made it their business’s core and trump card. Even their choice of beer surprises me. ‘Local beers only, of course,’ Mattia explains. The beer labelled Molise non esiste – Molise doesn’t exist – is particularly unique. But whatever the beer says, Molise certainly exists here. Bravo!

Garage Moto Kafè C.so Giuseppe Garibaldi 211, Isernia

The handmade orecchiette are Apulia’s pride. In almost every household, you will find the traditional wooden plank upon which kilos of fresh pasta are made. The name orecchietta in the singular refers to the pasta’s shape: a ‘little ear’. Walking down the streets of old Bari, I pass women selling handmade orecchiette on their doorstep. They make grateful use of tables, planks and rolling pins. Via dell’Arco Basso, better known as Via delle Orecchiette, is the place to be for fresh homemade pasta in the afternoons and early evenings. I walk from the bar across from the N-dèrre a la lanze towards the old town, and after some 700 metres, I reach Via dell’Arco Basso with its rich folklore, colours, women and orecchiette.

Angela Lastella nimbly cuts the pasta into balls and presses them into an ear shapes. Angela: ‘I have been doing this my entire life. I make the ears from semolina, water and salt. I leave the pasta to dry on our balcony, next to our jogging bottoms, T-shirts and bath towels.’ One of the locals buys a kilo of pasta. Angela checks the weight on an ancient scale. ‘Everything’s always fresh here,’ she says. Through the kitchen window, I spy sauce pots simmering away next to large sacks of semolina flour. An Italian TV show blares in the background.

This street is no tourist trap; this is where the locals come to buy their fresh pasta. This tradition is sacred. You will find pasta in all flavours, shapes and sizes, but Bari’s true soul can be found in the orecchiette. These women drew masses of cruise ship passengers and turned Bari into one of Lonely Planet’s European highlights. They were also the inspiration for one of Dolce & Gabbana’s cosmetics advertisements. In ‘Pasta, Amore e Emotioneyes’, Sylvester Stallone’s grown-up daughters parade in black negligees down ‘Orecchiette Street’ while the grandmas laugh, dance and make pasta.

Orecchiette in Arco Basso 1/25, Bari

The most traditional sauce is made with broccoli rabe, or cime di rapa. This is an Italian vegetable with thick stems and flat green leaves, both used in Italian cuisine. In Bari, they’re also called rapini or broccoletti. This slightly bitter green vegetable tastes divine in olive oil. The stems need to cook a little longer than the leaves and florets. You briefly fry them in a saucepan with garlic and olive oil, then add a pinch of salt before serving. According to the Apulians, orecchiette and cime di rapa belong together. A sauce made from tomatoes and basil, sometimes with small meatballs thrown in, is also very popular. They are simple dishes born from poverty, but the first-class ingredients produce rich, pure flavours.

Calabria shares its history with Basilicata and Apulia. In ancient times, the region formed the heart of a powerful and prosperous Greek colony. After the Greeks, the Romans, Byzantines, Lombards, Vikings, Hohenstaufen or Swabians, Angevins and Bourbons all reigned here at some point. Later, the southern region was an Italian republican stronghold until the Risorgimento, the unification of Italy. In 1860, Calabria joined the kingdom of Italy under the republican revolutionary, Giuseppe Garibaldi. This general was welcomed as the liberator from Bourbon tyranny. Italians consider Giuseppe Garibaldi a national hero.

Agriculture is the foundation of this mountainous region’s economy. In the olden days, large country estates, or latifundia, existed alongside tiny farmsteads. The farms were almost entirely devoted to grains, olives, sheep and goats. Soil erosion and primitive agricultural practices ensured that Calabria remained one of the poorest regions in Italy for a long time. Starting in the 1950s, agricultural reforms and government investments led to newer, more profitable crops. Today, the Calabrians not only earn their living from the agrifood industry; they’re proud of it.

The Calabrian mafia, known as the ‘Ndrangheta’, impedes economic growth. The same goes for the rough, mountainous interior, earthquakes and poor infrastructure. The railroads primarily serve the coastal areas, but beyond that, there is hardly any industry. Catanzaro, Reggio di Calabria and Cosenza are the only cities of notable size.

Life in Calabria has always been hard, which explains why many people sought their fortune elsewhere. Speak to any Calabrian, and they’ll undoubtedly tell you they have cousins somewhere in America, Australia, or elsewhere in Europe. The Calabrians are masters in the art of living. They like to talk and sing and have hearts as vast as the azure-blue sea.

Calabria pulls out all the stops when it comes to typical, southern Italian, Mediterranean cuisine, including meat dishes (pork, lamb and goat) with plenty of vegetables, especially aubergine, and a little fish. Despite Calabria’s vast coastline, there is no significant gastronomical tradition involving fish. The sea is seen more as an enemy than a friend, given that foreign invaders and pirates often came from the sea.

A whole range of products has a protected quality, or IGP label. IGP products include the cipolla rossa di Tropea, the red onion from Tropea, potatoes from Sila, and ‘nduja from Spilinga. Examples of DOP products include sopressata (cured salami), caciocavallo cheese and bergamotto, a citrus fruit from Reggio Calabria.

In ancient times, the Greeks called Calabria Enotria, ‘the land of wine’. Some vineyards’ origins date back to the ancient Greek colony. The most famous DOC wines are the cirò from the province of Crotone and the donnici from the province of Cosenza. The red gaglioppo and white greco are the best-known grape varieties. Calabria has also made a name for itself with its amaro digestives, including the Vecchio Amaro del Capo, which has a complex flavour palate of mint, aniseed, orange, and liquorice.

My Calabria road trip starts at the Riviera dei Cedri on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea in the northwest. The region owes its name to the local citrus fruit, cedro, a unique variety of giant lemon. This lemon country stretches from Tortora on the northern border to the town of Paola further south along the coast. Diamante is situated halfway. In September, the town holds a week-long festival honouring the region’s star product: the pepperoncino, or chilli pepper. Diamante, also known for its many murals, is where I meet Enzo Monaco. He’s chairman of the Academia Italiana del Peperoncino and a self-professed fan of His Royal Highness, the chilli pepper!

Enzo: ‘The pepperoncino means everything to us, not only in terms of nutrition and gastronomy but also as a cultural symbol. The hot, red spice reflects the Calabrian spirit Anthropologists ascribe the following characteristics to this fiery red pepper: duro (hard), bastarde (bastard), brigante (bandit), violente (violent) and sensuale (sensual). This characterisation is not based on science, of course,’ Enzo says with a wink.

‘Whenever Calabrians travel anywhere,’ he continues, ‘they always pack some pepperoncino in their suitcase. Today, the chilli pepper is crushed or ground in a mortar and pestle and stored in a small silver container for travel.’

Enzo shows me a small container attached to a keychain that Liz Taylor’s goldsmith, Gerardo Sacco, designed for the academy. The dried powder is kept in a tiny holder shaped like a pepperoncino. Enzo: ‘The Aztecs, Mayas and Incas cultivated chilli pepper thousands of years ago. Through the centuries, it was considered a holy fruit, a medicine, an aphrodisiac, a preservative and an excellent seasoning. The chilli peppers ended up in Europe after Christopher Columbus discovered America. This plant, which takes root in practically anything, even in a pot, flourishes wonderfully in our poor soil.’

A poster on the wall displays peppers of all shapes and sizes with various names. Enzo: ‘Axi was the name the indigenous people gave to chilli peppers in the time of Christopher Columbus. In Europe, we called the spice Indian pepper, horned pepper, and siliquastro. The term peperoncino is the diminutive of peperone, the sweet pepper. The peperoncino group includes many different varieties. We do not have a specific variety with a DOP or IGP quality label in Calabria, like they do in Spain or France. Just to give you an idea of the variety of spicy peppers out there: there’s habanero (the spiciest variety), chilli d’Espelette (French), piquillo de Lodosa (Spanish), tabasco (Louisiana), cayenne (Mexico), Diavolicchio Diamante (Calabria), Naga Morich (India), Big Jim (New Mexico), chiltepin (Mexico)…’

Sicily is situated a mere 160 kilometres north-east of Tunisia (Northern Africa). The Strait of Messina separates this island from the mainland. It takes me half an hour to make the eight-kilometre crossing by car ferry.

History, rich traditions and delicious food are the highlights of this island, the largest in Italy and the Mediterranean Sea. It is home to the picturesque, historical and vibrant towns of Taormina, Palermo, Catania, Cefalù and Siracuse. Palermo is Sicily’s capital and Mount Etna, the volcano, is the eternally burning heart of this fascinating island. Sicily’s necklace of pearls includes other treasures, such as the northern Aeolian Islands near Messina and the Aegadian Islands near Trapani. Lampedusa and Pantelleria are situated further south in the Mediterranean Sea, halfway between Sicily and Tunisia. In Sicily, you can enjoy the sea ten months a year, thanks to its mild climate. The former king of Sicily, Frederick II, Duke of Swabia, summed Sicily up as follows: ‘I do not envy God’s paradise because I’m well-pleased to live in Sicily.’

The following day, I stop in Taormina for a breakfast of brioche with granita, and I heartily agree with Peppe. An experience like this is unsurpassed, one for my personal bucket list. Taormina is beautifully situated atop a hill on the east coast. The ancient Greek-Roman theatre draws tourists in droves. Pristine sandy beaches lie tucked away between tall cliffs. I visit pasticceria/ gelateria Nonna Rosa in the old town.

I order a granita caffè con panna e brioche, or coffeeflavoured granita with whipped cream and a brioche. I settle down at a table outside. The theatre and the ice demand love and endorsement. Experience it for yourself, and you’ll know what I mean. The glass in front of me, the spoon and the buttery brioche on the plate demand my full attention. The ice heaps just long enough on my spoon, only to melt away in an instant in my mouth. The granita is just perfect; not too icy or grainy, but not entirely smooth either. I now dip my brioche in the glass with the granita and cream as is the custom. The coffee, the cream, the buttery pastry... intense!

From Taormino, I drive the last 50 kilometres to the port of Messina, from where I will continue my journey by boat to Sardinia. But first, I go off in search of a typical street food dish: the rustic, half-moon-shaped pitoni or pidoni. This pastry looks like a fried calzone or folded-over pizza. Pitoni messinesi is what this Sicilian town is best known for in terms of street food. You can try arancino on every street corner in Italy, but for pitoni, you have to travel to Messina.

La Boutique Del Pane in the heart of the city is my next stop. Salvatore and Tommaso Cannata also run the panificio focacceria rosticceria in Milan. Salvatore is a fourth-generation master baker who makes daily use of high-quality, traditional Sicilian grains and ingredients. Signora Chiara takes me on a guided tour through their assortment: ‘We bake more than twenty types of bread, including the famous Tumminia bread with Sicilian almonds and black olives. In addition to the many types of bread, we also have pitoni, arancini messinesi, focaccia, pizza, biscuits and sweet pastries.’

I order a pitone and ask Chiara what makes this product unique among the many versions of ‘pizza’ you find on Italian soil. Chiara: ‘The pitone is distinctive because of the soft dough, the gold-coloured breadcrumbs, and the rich filling with local ingredients. The rustico originated in the peasant kitchen. In Messina, people would bake scraps of bread dough into half-moons filled with pieces of cheese and escarole, or endive. The pitoni doesn’t have an official recipe or preparation method. The dough doesn’t contain any yeast, which is why most recipes use lard or margarine to soften the dough instead. We fry the filled dough in hot oil.’

Cannata – La Boutique Del Pane Via XXVII Luglio 83/85, Messina

The southern Italian region of Campania is situated on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea, with Lazio to the north, Basilicata to the south and Molise and Puglia to the east. The Romans called this fertile region ‘Campania felix’. Natural springs rise up from the deep, soft soil at different locations. Sunshine, enough rain and the fresh sea breeze ensure a pleasant climate. Its ecosystems are varied; from Mediterranean coastal areas to mountain ridges. Popular destinations include the Amalfi Coast, with its intense colours and gorgeous bays and cliffs, and the islands of Capri, Ischia and Procida. The region also boasts two national parks, nine regional parks and 18 nature and marine reserves. The reserves take up about 27 per cent of the Campania’s total surface area; a figure surpassed only by Abruzzo.

The region features no fewer than five UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the historical centre of Napoli, the archaeological sites of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, the 18th-century royal palace of Caserta, the Amalfi Coast and the Cliento and Vallo Diano national parks. They exemplify Campania’s rich history, cultural heritage and exceptional natural beauty.

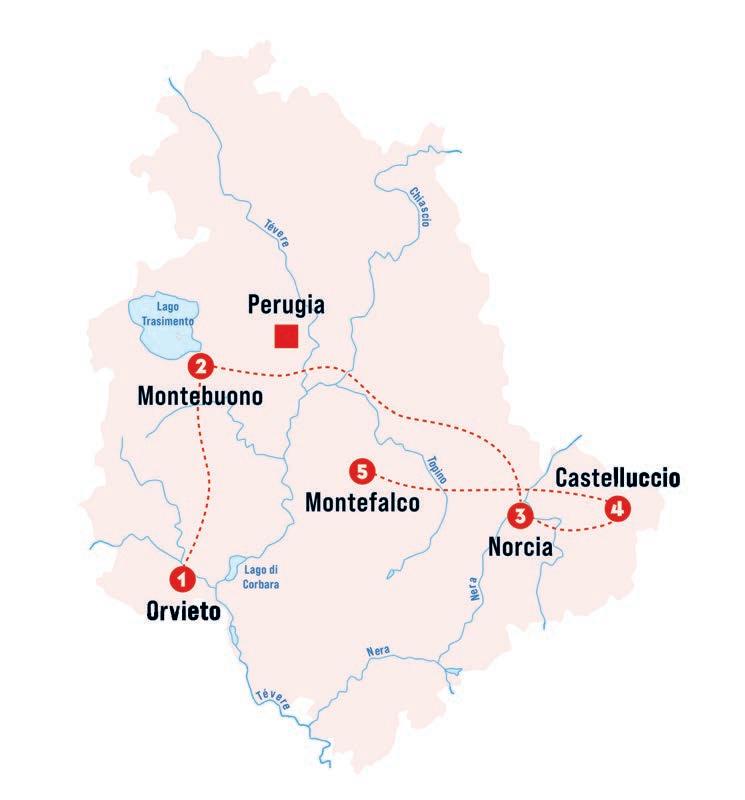

Umbria is situated between Tuscany, Lazio, and Marche. The capital is Perugia. There’s a reason why it’s called the ‘green heart of Italy’. I am entirely enthralled with the fairy-tale-like natural surroundings, from Monti Sibillini to the Marmore Falls. The hills are carpeted with trees, meadows, olive trees and vineyards. And with a bit of luck, you will come across a shepherd with his flock on the upland plains. The national park is home to wolves, ibexes, and birds of prey.

Umbria is a mosaic of landscapes. In the highlands, water and land alternate seamlessly in a picturesque whole as rivers twist and turn through impressive gorges and falls. Lago Trasimeno is the fourth-largest lake in Italy. I drive past medieval towns and villages surrounded by greenery. The pilgrim towns of Assisi, Cascia and Città di Castello add a spiritual dimension.

I got married in a small, picturesque village in bella Italia and temporarily moved to Tuscany for my work with the Thomas More College as a guide for exchange students from the Journalism department. And so, in 2006, I became an honorary citizen of Sinalunga. My children, Ramona, Vittorio, and Lorena went to school with the ‘suore’, the sisters. I made a lot of friends in Tuscany. The ‘amici della chianina’ (Society of Friends of the Chianina cattle breed), my neighbour, who was an olive grower, and a few local chefs drew me into their culture and fascinating stories. After Thomas More, I took a post as a researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels’ SMIT (Studies in Media, Innovation and Technology) department. My curious nature drove me to keep searching for new challenges. I moved to Antwerp, where I dedicated my heart and soul to running Sette Piatti, an Italian catering and delicatessen shop that caters to Italophiles everywhere. All these experiences have come together in this book. Which goes to show, destiny always finds its way!

www.gustoeamore.com www.instagram.com/annet.cibodistrada/ www.tiktok.com/@annet.cibodistrada

www.lannoo.com

Sign up for our newsletter with news about new and forthcoming publications as well as exclusive offers and events.

If you have any questions or comments about this book, please do not hesitate to contact our editorial team: info@lannoo.be

Texts

Annette Canini-Daems

Translation

Textcase, Deventer

Photography

Annette Canini-Daems, with additional images taken from iStock

Cover & book design

Letterwerf, Klaartje De Buck

Typesetting

Rogier Stoel, rogierstoel.nl

Maps

Myrthe Van Rompaey

© Lannoo Publishers, Belgium, 2024

D/2024/45/273 – NUR 512 & 442

ISBN 978-94-014-9906-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form of by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.