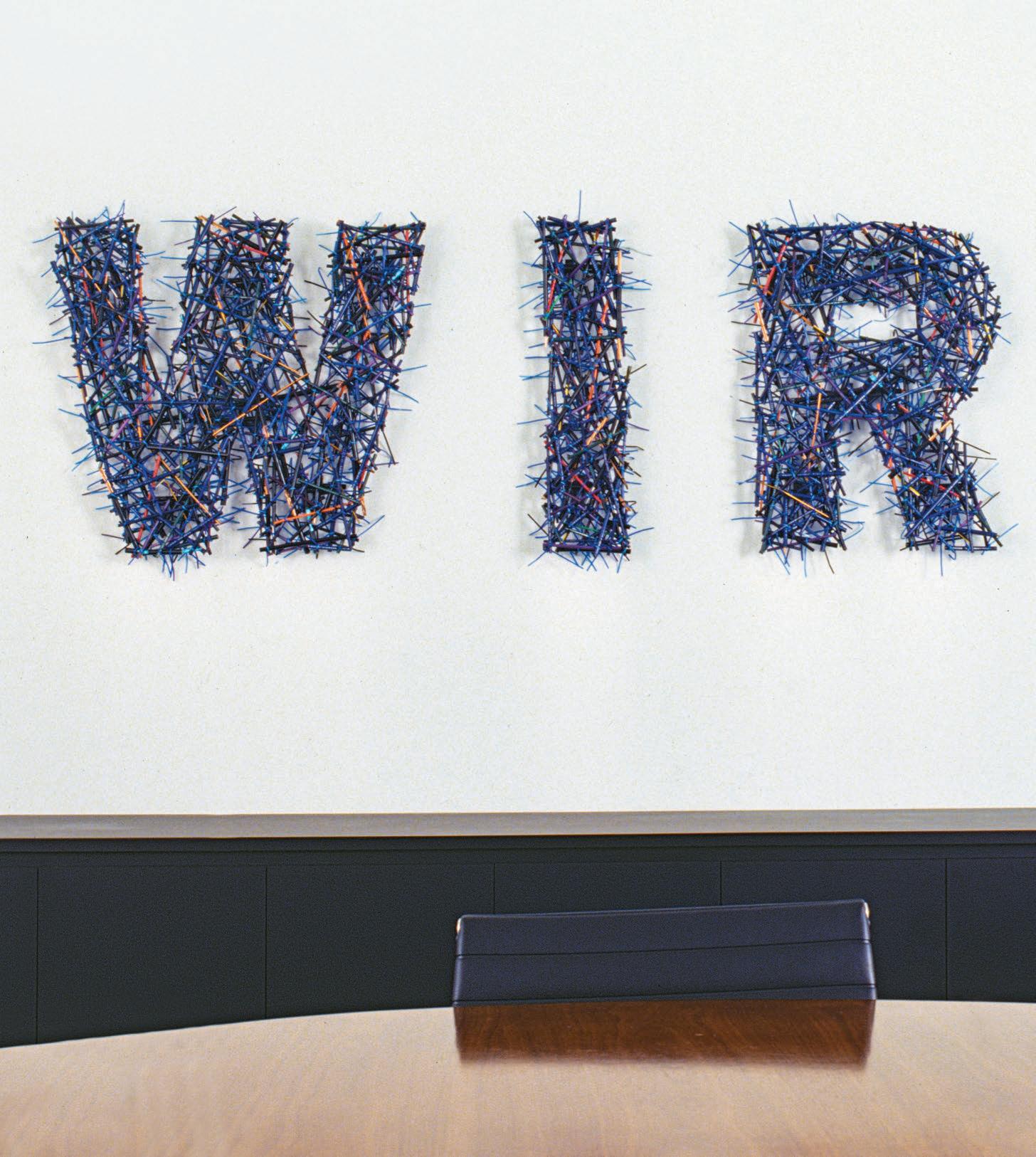

Gyöngy

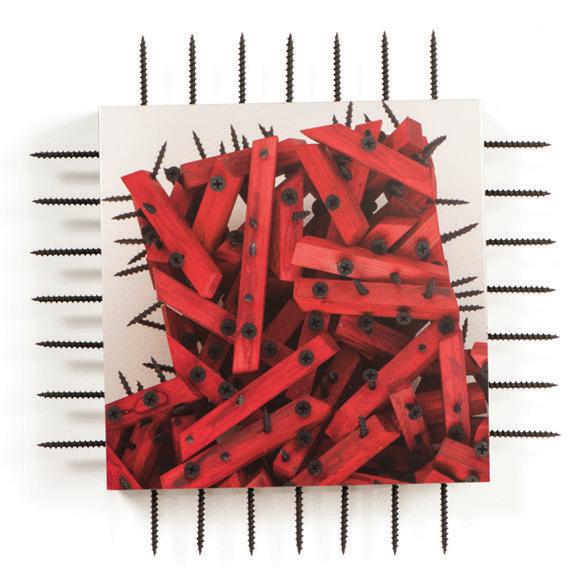

Screwing with Order

assembled art, actions and creative practice

Screwing with Order

assembled art, actions and creative practice

Mija Riedel

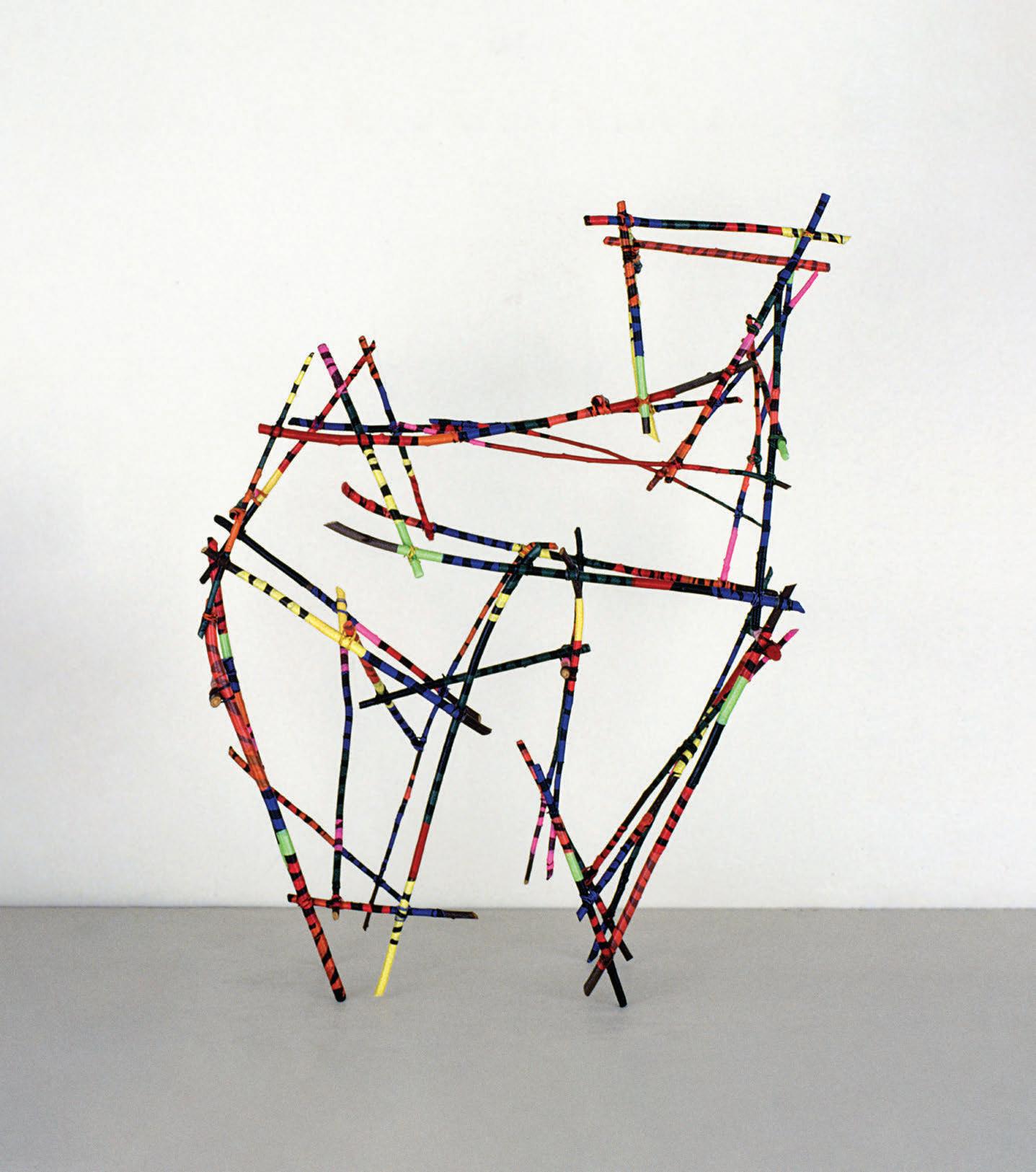

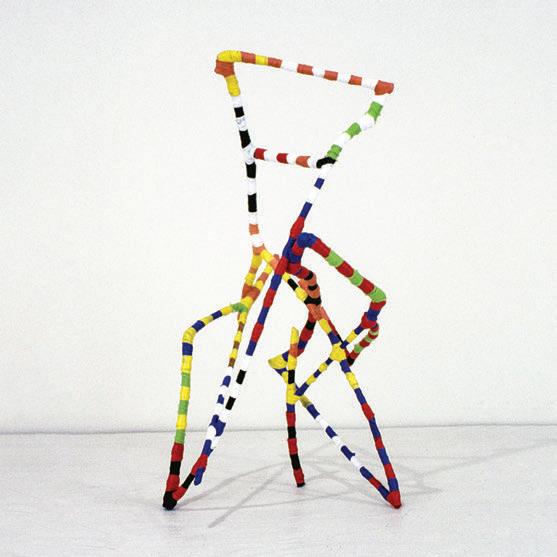

In a short, 2007 San Francisco Magazine article, Jonathon Keats, the writer and conceptual artist, dubbed Gyöngy Laky the “wood whisperer.”1 A sculptor, not easy to categorize, she has variously been described as a textile/fiber, conceptual, environmental and activist artist. Her unique, puzzle-like assemblages have roots in her unconventional personal story: born amid the bombing raids of World War II, she escaped from post-war, Soviet-dominated Hungary into Austria, then via refugee boat to Ellis Island, and on to Ohio, Oklahoma,Texas and California. Laky’s early years are key to who she would become as an artist and a person—her inclination to cross boundaries, play with language, and champion diversity and human rights. Art as a vital endeavor—worth pursuing and protecting, even in dire conditions—was a lesson she absorbed early and that sustains her studio practice still.

Newcomer

Laky was born in Budapest in February 1944 as fighting between the Nazis, Hungarians and the Russians was intensifying. To escape the worst of it, her family fled to their small vineyard, in Baj, 50 miles northwest of the city. That December, the Siege of Budapest launched. Hundreds of thousands died, including 38,000 civilians. Baj did not escape the violence, but became the front line of escalating fighting. On Laky’s first birthday, Budapest surrendered.

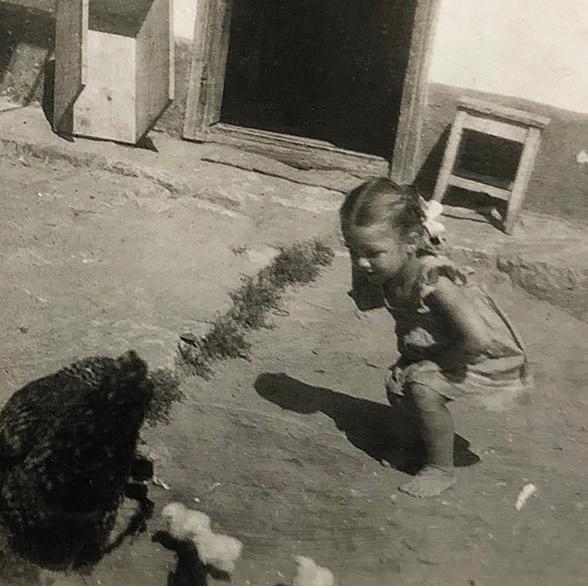

Over the next few years, her family shuttled between Baj and Budapest, a city once famous for its architecture and bridges, now in ruins. Laky took her first steps on earth pitted with bomb craters. There was no work and no income. Finally, Laky’s father, Laszlo, who had been the manager of Steaua Oil Company in Budapest, was offered a job in Austria with the Red Cross, helping to feed and clothe refugees. In an

3 or 4, 1947–1948

frequenting the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and mulling over the university’s collection of 8,000-plus Native Californian baskets.

To be fair, Laky was unusually well prepared to recognize what Rossbach had to offer. Fellow student Chere Lai Mah noted, “Of all the people in Ed’s group, only Gyöngy had this early, wide-ranging experience— working in a gallery, being European transposed to the US, familiar with the greatest Chinese painter alive.”21

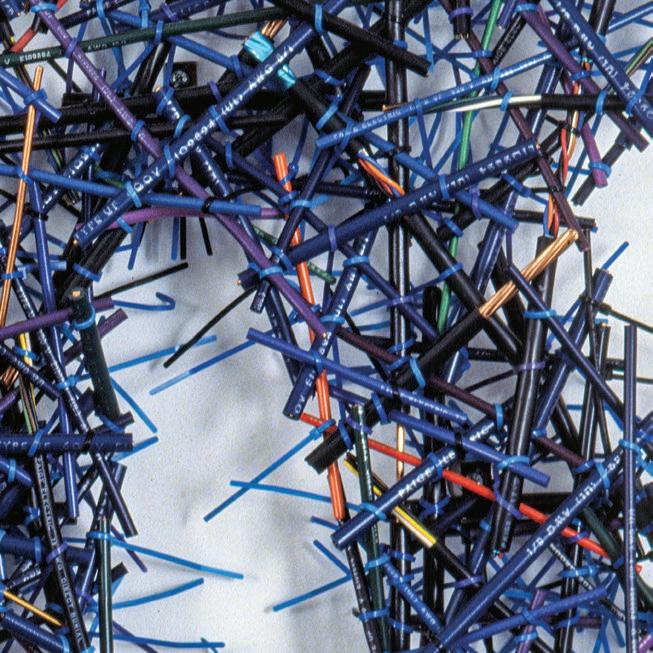

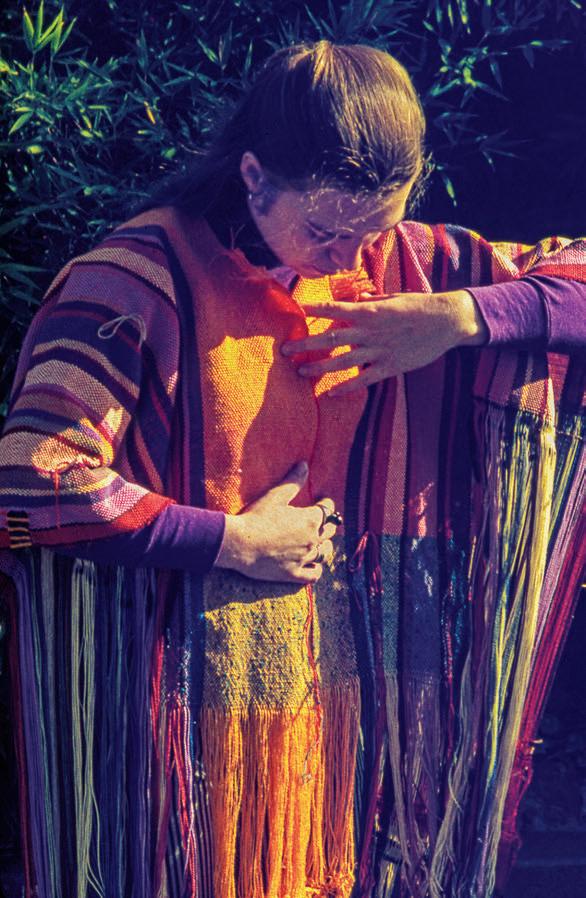

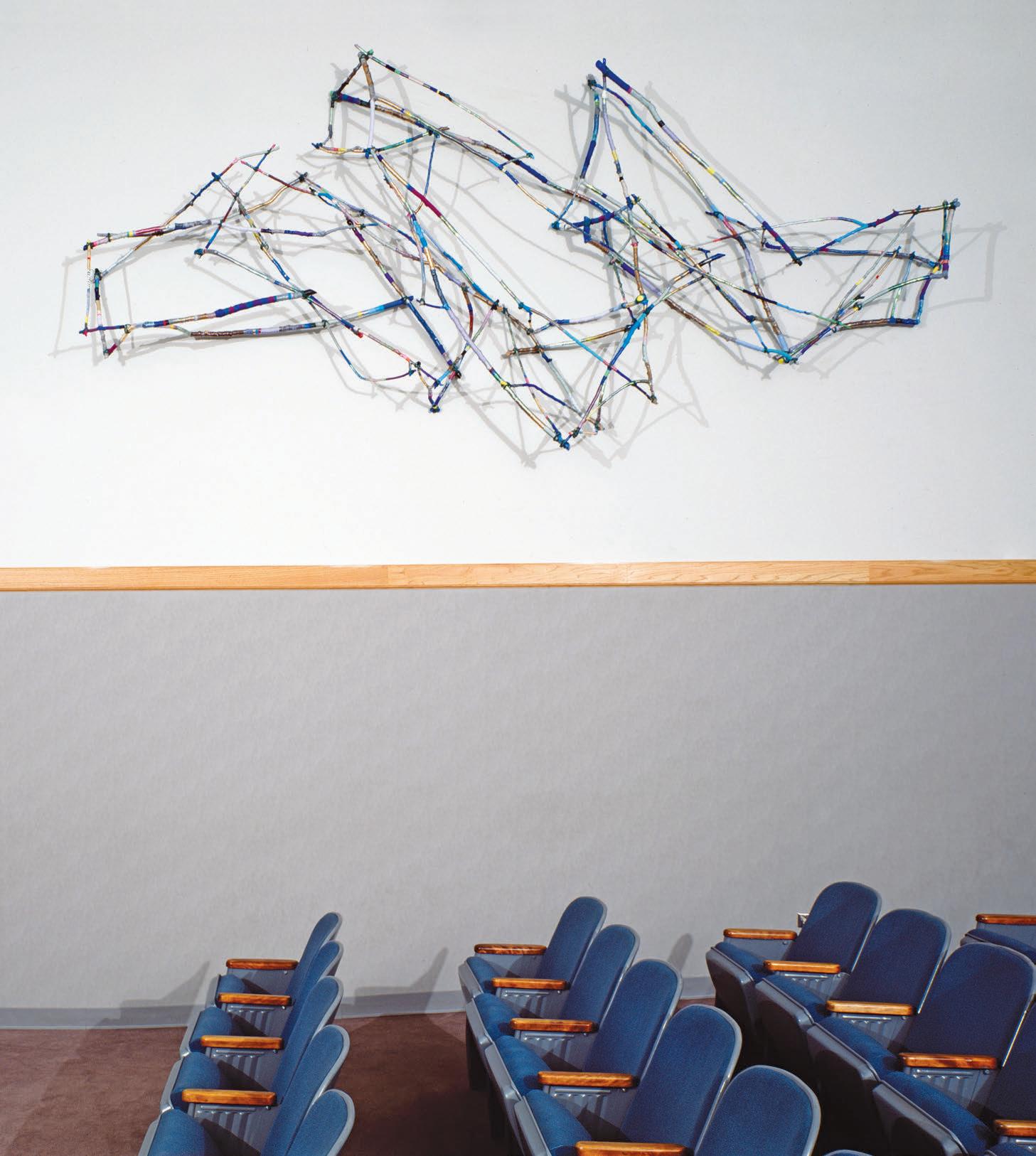

Soon, Laky was finding connections to textiles everywhere—in “how nature is put together, how trees grow, the sinews and the veins in the body, and what neurons looks like.”22 Even metal came in sheets that could be folded, like blankets, or pleated (it just required a little more effort). This “little corner of the art world,” she said, “opened me to the entire world and to history and to people and to different cultures.”23 For thousands of years, Peruvian artisans had been spinning grass into bridges. Bolivian Indians tied reeds into fishing canoes. English roofs were woven with thatch, Chinese scaffolding made with bamboo and buildings in Iraq constructed from reeds. The Inca invented a system of knotted strings, quipu (khipu), to keep records, accounts, and communicate information. Without spinning and rope making, there would be no steel cables suspending bridges.

Increasingly, Laky immersed herself in textile history and techniques. The monumental role of the humble, ubiquitous strip, strand, string, yarn, wire or vine captured her attention and sparked her imagination. These basic linear elements initiated endless possibilities. She braided and spun rope. She wove tubes and stuffed them, wove with copper wire, and experimented with multiple woven and hand-construction techniques. Some of Laky’s earliest works, such as This is My Plastic Bag, 1969, p. 18, contained threads of the complex meaning and humor that would weave its way into her later sculptures. Constructed with linear

elements spun from plastic shopping bags, then woven in a traditional coverlet pattern, the piece’s design recalls the beauty and ingenuity of Bolivian chuspa or coca bags. Laky’s version, however, is massive —60 by 144 inches— in comparison to a chuspa or coca bag and her tongue-in-cheek title—a nod toward Magritte—fused in additional, fresh layers of reference.

As a student, Laky gathered her first branches and coiled and knotted her first basket, Kikapu , 1968, p. 18. Unlike glass blowing, basket weaving wasn’t dangerous or physically demanding, but Laky found it as compelling as the hot shop.24 Her college housemate and lifelong friend, the painter Judy Foosaner, recalls Laky arriving at their home a mile above campus, dragging huge bundles of prunings. Laky cured the branches in her “studio” (a corner of their living room), then built them, said Foosaner, into “unpainted, unembellished, completely natural, beautiful linear forms. She was building baskets, some so huge you could stand in them.”25 Foosaner admired Laky’s sensitivity to her materials as well as her ability to assemble them with “invisible mechanics.” When she was done, Laky had created something that hadn’t existed before, from humble materials that had appeared to be something else when she started.26

Laky was also passionately engaged in activities outside the classroom. The counterculture that she’d glimpsed at Nepenthe and Big Sur was in full force in Berkeley, and a flood of contemporary crises—the Vietnam war, polluted water and air, endangered species, civil rights and women’s rights—were connecting groups of students who might not otherwise have met. Laky joined undergrads setting up an alternative classroom in the College of Environmental Design. She installed her first site-specific work there, a massive, suspended net and, in the same space, Laky and fellow students founded the unauthorized Ramona’s Café, which offered healthier, less-processed food (now Rice and Bones cafe, by Chef Charles Phan).

“For Laky, a basket seems to boil down to connected lines suggesting a volume — as broad a definition as that . . . She can make this age-old invention specific to our times by blending apparently unrelated materials, this blend then symbolizing the exciting juxtapositions of a global culture.”

Janet Koplos

“In Natura Facit Saltum, applewood forms a large tapered vessel with a smooth orange interior but on the exterior, a massing entanglement of lines that again makes use of nature’s extraordinary linear shapes.”

Marion S. Lee