With the patronage of

With the patronage and contribution of

As part of

Promoted and organized by

With the support of

In collaboration with

comitato nazionale per le celebrazioni

dei settecento anni dalla morte di dante alighieri

musei del bargello

università degli studi di firenze, dipartimento dilef

dipartimento sagas

Co-promoters

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze

Biblioteca Riccardiana

MUSEI DEL BARGELLO

Director

Paola D’Agostino

Governing board

Paola D’Agostino, presidente

Silvia Calandrelli

Stefano Casciu

Giuseppe Gherpelli

Stefano Passigli

Advisory council

Paola D’Agostino, chair

Adriano Aymonino

Francesco Caglioti

Davide Gasparotto

Maddalena Ragni

Auditors

Sergio Salustri, chair

Luigi Lari

Antonio Martini

Secretary to the director

Silvia Vettori

Adminisrative office

Laura Pistilli with Federica Suppi, Alessandra Vannini, Lucia Verdi

Technical office

Maria Cristina Valenti with Vincenzo De Magistris

Michele Martino

Exhibitions office

Andrea Staderini

Silvia Vettori

Technical team

Vincenzo De Magistris

Communications and promotions office

Riccardo Artico with Barbara Bonora, Andrea Staderini

Museo Nazionale del Bargello security coordination

Guglielmo Lorenzini

Carla Secciani

Exhibition curated by Luca Azzetta, Sonia Chiodo, Teresa De Robertis

Advisory council to the exhibition

Luca Azzetta, Sonia Chiodo, Paola D’Agostino, Andrea De Marchi, Teresa De Robertis, Giovanna Frosini, Andrea Mazzucchi, Marco Petoletti, Stefano Zamponi

Installation and exhibition design

Luigi Cupellini

Exhibition graphic design

Claudio Chiarusi

Exhibition graphics

Stampa in Stampa s.r.l.

Accompanying texts in the exhibition

Luca Azzetta, Sonia Chiodo, Teresa De Robertis

Translation of accompanying texts in the exhibition

Stephen Tobin (Italian-English)

Exhibition installation

Opera Laboratori,

Piero Castri and Pietro Alongi

Multimedia equipment

Opera Laboratori, Alessandro Modena

Audio narration

Lorenzo Carcasci – actor

Alice Bologna – vocal coach

In collaboration with the Associazione Oltrarno

e il Teatro della Toscana

Promotion and communication

Opera Laboratori, Mariella Becherini

Press office

Opera Laboratori, Andrea Acampa

Università di Firenze, Antonella Maraviglia

Musei del Bargello, Ludovica Zarrilli

Transport and assembly

Arterìa s.r.l.

Insurance

Willis Towers Watson

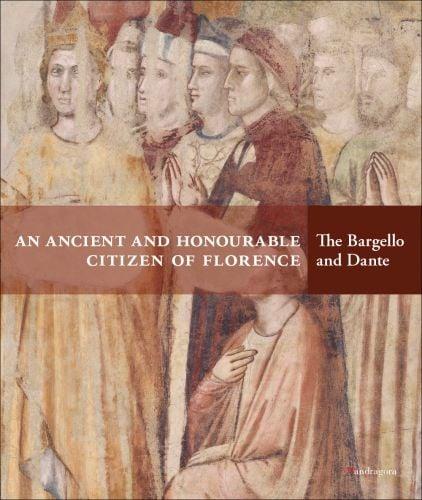

“an ancient and honourable citizen of f lorence”

The Bargello and Dante

Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 21 April–31 July 2021

curated by Luca Azzetta, Sonia Chiodo, Teresa De Robertis

Lenders

Fiesole, Diocesi di Fiesole, Museo Bandini

Florence, Accademia della Crusca

Florence, Archivio di Stato

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale

Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana

Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia

Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Archivio storico civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana

Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Raccolte d’arte antica

Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Rivoli (To), Castello di Rivoli, Collezione Cerruti

Toledo, Catedral Primada, Archivo y Biblioteca Capitulares

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana

CATALOGUE

Essays

Luca Azzetta

Monica Berté

Irene Ceccherini

Sonia Chiodo

Andrea De Marchi

Teresa De Robertis

Giovanna Frosini

Andrea Mazzucchi

Giuliano Milani

Francesca Pasut

Marco Petoletti

Andrea Zorzi

Entries

Luca Azzetta (13, 34, 35, 37, 40, 42)

Giovanni Boccardo (33)

Martina Bordone (3, 22, 42)

Luca Boschetto (9)

Irene Ceccherini (24–31, 43)

Vittorio Celotto (2, 36, 51, 54)

Sonia Chiodo (6, 14, 15, 17–21, 26, 27, 32, 34, 53)

Teresa De Robertis (10, 12, 20–2, 32, 49, 52, 53)

Chiara Demaria (7, 8)

Sara Ferrilli (3)

Maurizio Fiorilla (55)

Giovanna Frosini (57)

Claudio Lagomarsini (39)

Leonardo Lenzi (23, 45, 46, 48)

Francesca Pasut (9, 16, 49)

Marco Petoletti (4, 5, 38, 41, 47)

Simone Pregnolato (58–61)

Roberto Rea (11)

Laura Regnicoli (1)

Stefano Zamponi (44)

Martina Zanghì (27, 50, 56)

Indices

Leonardo Lenzi

Editor

Marco Salucci

Translation

Sonia Hill

Ian Mansbridge

Sarah Ponting

Oona Smyth

Art director

Paola Vannucchi

Editorial secretary

Luca Pileri

Prepress

Puntoeacapo, Florence

Printing

Grafiche Martinelli, Bagno a Ripoli (Florence)

Binding

Legatoria Giagnoni, Calenzano (Florence)

Acknowledgements

The catalogue and exhibition have been made possible thanks to the contribution of many different people and organizations who offered their generous support. The Musei del Bargello and the Università di Firenze would like to thank all of them: the directors of the museums, archives and libraries and all those who were personally involved in organizing the loans.

Special thanks to Dita Amory, Luca Bellingeri, Ilaria Ciseri, Keith Christiansen, Ottaviano Caruso, Marco Ciatti, Andrea Di Lorenzo, Anna Rita Fantoni, Cecilia Frosinini, Francesca Gallori, Sarah E. Lawrence, Sabrina Magrini, Giovanni Martellucci, Nicoletta Matteuzzi, Pierluigi Minari, Marylin Palmeri, Sara Penoni, Andrea Pessina, Alessandro Righi, Cristina Todaro, Frank Truijllo, Maria Cristina Valenti, Gabriella Zaccheddu, Andrea Zorzi and the donors who prefer to remain anonymous, but who funded the English translation of the catalogue.

Our thanks to the co-promoters: the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana and the Biblioteca Riccardiana.

Dante, Giotto and the Comedy Fragments of a possible discourse in the paintings of the Podestà Chapel

When reconstructing the relationship between Dante and Florence in the decades immediately after his death, during the night between 13 and 14 September 1321, a key role touches upon the question of the poet’s portrait – either real or presumed – in the paintings in the chapel of the Palazzo del Podestà (fig. 1). The matter must therefore be at least summed up in brief. The chapel houses a cycle of wall paintings, unfortunately severely damaged, which show Paradise on the altar wall and Hell on the counterfaçade, while the Stories of Mary Magdalene occupy the entire south wall and part of the north wall; the latter also includes two scenes from the life of St John the Baptist and the standing figure of St Venantius between the windows, accompanied by an inscription that tells us that the cycle was completed during the podesteria of Fidesmino da Varano, namely in the second half of 1337. For some time now, critics have associated the enterprise with Giotto’s workshop, ruling out his direct contribution or at least limiting it to little more than the design phase, given that sources record his death as having taken place on 8 January of that same year. Despite taking a cautious approach to references with controversial interpretations such as the verses of Antonio Pucci, which nevertheless have the advantage of a very early date in the first half of the 14th century, the first explicit (and incontrovertible) reference to the existence of an effigy of Dante in these paintings, to be more specific among the elect in Paradise, is to be found in Filippo Villani’s celebration of illustrious Florentines written in the early 1380s, during the same period that another ‘portrait’ of Dante, unfortunately lost, was included in the cycle of Illustrious Men painted in the audience chamber of the Palazzo della Signoria, under the conceptual supervision of Coluccio Salutati, while yet another was painted a few years later in the hearing room of the Arte dei Giudici e Notai, where we can still admire it today (Chiodo, Ritratti di Dante, pp. 340–1, 348–57; fig. 2). By the last quarter of the century, it had become established that the poet should be included among the literary glories that made Florence the ‘new Rome’. Later, at the height of the 15th century, the effigy handed down by these earlier iconographical sources merged with Giovanni Boccaccio’s admirable physical and moral description in his commemoration of ancient portraits and found a new synthesis in the works of Andrea del Castagno, Domenico di Michelino and Sandro Botticelli. Ultimately, it touched upon Raphael to seal the effigy of Dante in the portrait that is imprinted on all of our minds. In the meantime, the Palazzo del Podestà underwent major changes that overturned and disfigured its internal structure, with an attic space being installed in the chapel that was transformed into cells for prisoners and its walls whitewashed, so that all trace of the 14th-century paintings was lost completely.

The thread of memory, which had been cut by history, was retied in the early 19th century. Within the new context of the search for the founding fathers of the Italian national identity, curiosity grew regarding the portrait mentioned in ancient sources, first and foremost by Giorgio Vasari: “among others, as is still seen to-day in the Chapel of the Palace of the Podestà at Florence, Dante Alighieri, a contemporary and his very great friend, and no less famous as poet than was in the same times Giotto as painter” (Lives, ed. De Vere, I, p. 97). The story of its recovery features an Englishman called Seymour S. Kirkup (London 1788–Livorno 1880), a schol-

1. Giotto and workshop, Paradise, detail with Dante Alighieri, Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Podestà Chapel.

s onia c hiodo

et gubernator of the city’s public works. Conversely, Bellosi (Giottino, p. 361) rightly wondered whether the “sweet manner […] with such great harmony” of Puccio Capanna and Giottino was really so far removed from the last developments of a multifarious genius like Giotto, noting how a “subtlety of description of the surface of things” could also be observed in some of his close Neapolitan followers, such as the painter of the exquisite Apocalypse panels in Stuttgart, which Boskovits attributed to Giotto himself (in Giotto. Bilancio critico, pp. 142–7).

However, the collocation of the Bargello murals in this final chapter of Giotto’s career on the basis of their conception, system of entablement, and compositional quality is challenged by a recurrent theory claiming that the layout and partial execution of the cycle dates from 1322 (Elliott, Judgement; Diacciati, L’immagine di Dante), when the wing of the palazzo had just been rebuilt as the residence for the Angevin king or his delegate and payments were made (January 1322) “in picturis capelle ipsius pallatji”. However, this theory can be categorically dismissed,

12. Andrea di Cione, known as Orcagna (?), Judgment of Brutus, detail, Florence, Palazzo dell’Arte della Lana, audience room.

as they could not have been for cycle. Indeed, the most recent restoration work discovered an underlying layer of painting (Mariotti, Le tecniche), although it may have been a far less complex aniconic decoration.

Leaving aside the tight unity of the cycle, whose dating is limited by the seal with multiple references to Fidesmino da Varano’s tenure as podestà, we have seen ample evidence that the figurative context of the frescos dates from the middle of the fourth decade of the 14th century, and certainly not from fifteen years earlier. Faced with so much evidence, I cannot see how it is possible to consider an argument for dating to 1322 the interpretation of the dedication to the Magdalene celebrated in the narrative cycle as a tribute to the royal house of Naples. The interpretation itself is not entirely unfounded; the miracle of the resurrection of the King of Provence’s son (figs. 4, 6) is widely depicted, e.g. in the Magdalene Chapel in Assisi (c. 1307), another place in the long shadow of the Angevin crown. The tribute to the House of Anjou was a

13. Giotto’s workshop (Puccio di Simone), Painted Cross, detail, Florence, Basilica of San Marco.

14. Giotto’s workshop (Master of San Lucchese?), Communion of the Magdalene, Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Podestà Chapel.

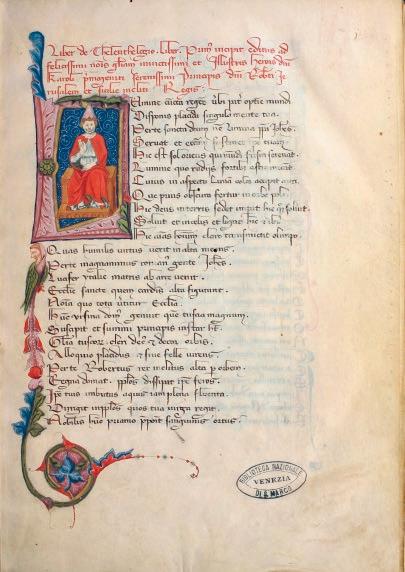

4. Teleutelogio by Ubaldus of Gubbio

Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Lat. VI 167 (3489)

Florence, 14th century, c. 1326–8.

illuminator: Circle of the Master of Paciano (oral communication by Sonia Chiodo).

Parchment; fols. A–B (paper), I–II (parchment), 42, A’–B’ (paper); quires 1–58, 62; catchwords; 280 × 197 mm (180 × 120 mm); ruled lines 29 / written lines 30; coloured ruling.

riga riga

Ubaldus of Gubbio, for whom little biographical information survives, is known in 14th-century literature and in the history of Dante’s fame thanks to his sole work, Teleutelogio, a prosimetrum on death, as the Greek-inspired title implies (Bartoli Langeli, Ubaldo; Donnini, Ubaldo da Gubbio. Teleutelogio; Bertin, Primi appunti). Ubaldus was a student in Bologna in June 1326, where his law masters included the esteemed Giovanni d’Andrea, to whom a medallion is dedicated in Teleutelogio (III 6), and then was in Florence from October to December 1327 as a valuation official in the entourage of Charles, Duke of Calabria, the first-born son of Robert, King of Naples, who was entrusted with control of Florence after Castruccio Castracani’s victory in Altopascio (23 November 1325). He is known for his work Teleutelogio, which harks back to the illustrious tradition of Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae in the way it alternates between prose and verse.

The work is divided into three books, each of which is in turn divided into chapters (which he calls collationes). The first book has ten collationes: after an introduction that praises Charles, Duke of Calabria (with warm words also given to the pope of the day, John XXII, and Cardinal Giovanni Caetani Orsini, a nephew of Pope Nicholas III and a legate in Italy in 1326 alongside Bertrand du Pouget, dealing with events in Tuscany), the book discusses the cruelty of death (I 2), its origins (I 3), human malice (I 3), the allure of death (I 4) and human qualities (I 5–10: science, beauty, honour, strength, nobility and wealth). Book II, divided into six collationes, describes the beauty of death and the reasons to desire it (such as the glory that death provides, access to eternal life and the vision of God). Book III, split into eight collationes, presents the seven deadly sins and their consequences (in order: pride, greed, lust, gluttony, wrath, envy and sloth) and, in the final chapter, disobedience. The style is refined and rhetorically complex, interwoven with poetic colour: the poet’s sources, as well as the ubiquitous Virgil (“ille tuus Virgilius Italus”) include Lucan, here called tragedus, Valerius Maximus, Seneca, Dares Phrygius, Aristotle (in Latin), the Bible and canon law, which also offers the author a small treasure trove of quotations on early Christianity. There is no shortage of references to contemporary events and to his personal experience, such as when Death leads

script: cancelleresca by the ‘Scribe of Parm’ (Parma, Bibl. Palatina, Parm. 3285). Probably autograph interventions by Ubaldus of Gubbio to correct errors; the letter dedicated to Francesco da Cingoli on fol. IIv. can also be attributed to him.

decoration: miniatures on fols. 1r and 15v, corresponding with the start of books I and II. The former, on fol. 1r, depicts a pope on the throne. binding: ancient wooden bords with a leather spine.

Ubaldus to recall another Gubbio resident, Andrea Magi (III 4), who “upon reading the ancient volumes by his pagan fathers, inspired by a great love for wine, his god, abandoned everything to serve this god, put to one side Justinian laws, sold the texts featuring the verdicts of Scaevola, Paul, Papinian and Ulpian and invested all the proceeds in drinking heavily in honour of his idol”. Other modern figures mentioned in Teleutelogio are Giotto: “who, thanks to his ingenuity, refreshed the art of painting to such an extent that the images he painted are so close to the natural features that they appear not painted as art, but produced by nature, lacking only movement and natural breath” (I 6); Peter ‘Tempesta’ (I 7), captain-general of the Guelph party in Tuscany who died in the famous battle of Montecatini in 1315, the son of Charles II of Naples, whom Dante, with blazing contempt, called the Cripple of Jerusalem in Paradise, and the brother of King Robert; the popes Nicholas III and Boniface VIII (I 8); and Charles I of Anjou, the son of Louis VIII, King of France (I 9), who is praised for his wisdom, power, strength, beauty, dignity and nobility, which led him to defeat King Manfred in Benevento in 1266 and Conradin in Tagliacozzo in 1268. It was, however, mostly Ubaldus’s explicit mention of Dante that guaranteed scholarly attention for the author and his prosimetrum.

In the chapter on lust (III 3), Dante is included in the list of those seduced by amorous passion: “Hec illa est que Dantem Alagherii, vestri temporis poetam, Florentinum civem, tue a teneris annis adolescentie preceptorem, inter humana ingenia nature dotibus coruscantem et omnium morum habitibus rutilantem, adulterinis amplexibus venenavit” (“It was she who with her adulterous embraces poisoned Dante Alighieri, poet of your time, citizen of Florence, guide of your youth from your earliest years, who shines among human ingenuity for his natural ability and glows with the possession of every good custom”). This passage has led some to surmise that Alighieri taught Ubaldus directly, but the noun preceptor has been rightly interpreted in a broad sense, without necessarily declaring a (highly unlikely) direct teacher-student relationship. Dante is also on the end of cutting remarks by the Guelph Ubaldus in the final chapter of Teleutelogio, which bitterly contests the political ideas he expressed in

Ubaldus of Gubbio, Teleutelogio (fols. 1r–41v), preceded by Lettera di dedica a Francesco da Cingoli (fol. IIv).

De Monarchia: the author is eager to respond to the incorrect ideas of those who equate papacy and empire, because a “magne scientie vir” is held in great esteem among those “qui sic insaniunt”. Teleutelogio therefore provides early evidence of the success of Dante’s treatise, which, after all, was known and challenged in the environments frequented by Ubaldus during his training (Coglievina, La leggenda, pp. 59–64; Bertin, Primi appunti).

Teleutelogio, meanwhile, was not very successful, with only two surviving manuscripts to document it: MSS Marciano and the 15th-century Laur. 13.16 (fols. 180r–220v). A faint trace of the reach of the dialogue is contained within an unusual and practically unknown work by the Pisan writer Niccolò di Lapo Lanfreducci entitled Disputatio, a lengthy complaint about his unfaithful wife, and about all women in general, composed at the very end of the 14th century (Petoletti, Una storia nascosta). In MS Marciano, transcribed by the renowned ‘Scribe of Parm’ (entry 27), Ubaldus’s hand has also been recognized circumstantially in certain interlinear interventions to correct errors made by the scribe, and above all in a sort of letter of dedication on fol. IIv, written in a different hand from the main scribe and addressed to Francesco Silvestri da Cingoli, bishop of Florence between 1323 and 1341 (Rossi, Da Dante a Leonardo, pp. 283–6; Bertin, Nuovi argomenti; Idem, Ubaldo). The miniature at the beginning, on fol. 1r, depicts a pope, probably Pope John XXII, who is praised in the initial poem, but it could also, to some extent, have referred to Francesco da Cingoli, hailed by Ubaldus in the short letter on fol. IIv as a second pope, “both for the dignity of his episcopal office and the generosity of his heart”, and explicitly held up as the meta and terminus of the author’s literary effort. Here Ubaldus explains the title’s meaning: “Est enim grece theleuthon, latine mors, logos sermo, quasi liber de sermone mortis, in quo multa maiorum dicta tam poetica quam philosofica, istoriagrapha atque iuridica aridus ager mei animi conglobavit” (“Thus in Greek theleuthon means “death” in Latin, and logos means “speech”, in other words a “Book that talks about death”, in which the arid field of my soul has gathered many words from the ancients, drawing them both from poetry and from philosophy, history and law”). The author then encourages the bishop to read at least the fi-

nal chapter, which discusses politics and debates the characteristics of papacy and empire. Nevertheless, it is worth bearing in mind that the first chapter is dedicated in its entirety to glorifying Charles, Duke of Calabria, who seems to be the main dedicatee of the work, as one can see in the initial rubric: “Liber primus incipit editus ad felicissimi nominis gloriam invictissimi et illustris herois domini Karoli Ducis Calabrie” (“Here begins the first book published in praise of the wonderful name of the undefeated and illustrious hero Charles, Duke of Calabria”). Ubaldus worked for the Angevin lord in Florence in 1327. Charles, Duke of Calabria died suddenly on 8 November 1328 in Naples, where he had returned after roughly a year of steering Florence through a particularly complicated political period between 1326 and 1327. One could surmise that Ubaldus, having once considered dedicating his work to the son of Robert, King of Naples, instead decided upon Charles’s death to update the dedication and send the work to the bishop of Florence to seek his protection and, perhaps, receive a position of office. This would provide a perfect explanation for the addition on fol. IIv of the letter addressed to Francesco da Cingoli, and would strengthen the hypothesis that this page is autograph. One could therefore suspect that the manuscript was written by the ‘Scribe of Parm’ maybe in 1327, after the beginning of Charles, Duke of Calabria’s governance of Florence (1326) and before his death (8 November 1328), with the letter of dedication to the bishop and the miniature produced immediately afterwards. What is certainly true is that this particular manuscript is recorded in one of Francesco da Cingoli’s inventories of books, confiscated by the Apostolic See upon his death through the ‘right of spoil’ and which, after various misadventures, ended up in the Collegio Gregoriano in Bologna in 1371 (entry 5) One of these lists of books, in which the compiler carefully indicated the start of the second leaf of each volume listed, also contains the following item: “Quendam librum intitulatum De teuletelogio, qui inc. in 2° folio || lucida”. As fol. 2r of the MS Marciano begins with the verse: “Lucida compositi solvatur machina mundi”, we can therefore say with certainty that it was one of the manuscripts in the bishop’s library in Florence.

The text is accompanied by several glosses in the margins, made by the scribe, mostly explaining difficult nouns or revealing the sources implied in the text. However, there is a strong suspicion that they were written by Ubaldus of Gubbio himself. The most frequently cited auctoritas is Virgil, but there is no shortage of references to Dares Phrygius (here called Cornelius, because Historia destructionis Troiae was preceded by an apocryphal letter addressed to Sallust from Cornelius Nepos), Bonaventure and the Decretum Gratiani

marco petoletti

Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Lat. VI 167 (3489), fol. 1r.

bibliography: Valentinelli, Bibliotheca, IV, pp. 205–6; Donnini, Ubaldo da Gubbio. Teleutelogio, pp. vi–vii; Pomaro, Frammenti, pp. 59–60; Bertin, Nuovi argomenti, pp. 80–1.

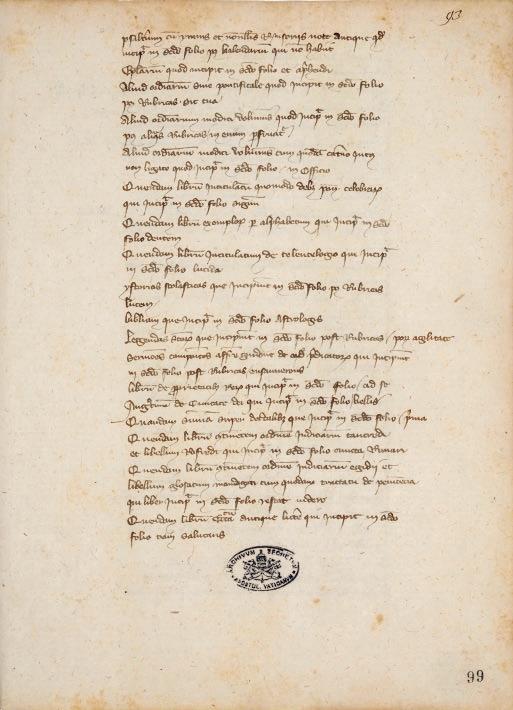

5. The libraries of the bishops of Florence Antonio degli Orsi († 1322) and Francesco Silvestri († 1341)

Vatican City, Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, Camera Apostolica, Collectoriae 244

Manuscript not on display

riga riga

The Archivio Apostolico Vaticano holds large volumes that include documents describing numerous libraries held by clerics active in the 14th century. They are predominantly reports of acquisitions made by officials from the Apostolic Camera upon exercising the right of spoil (“ius spolii”) that the Avignon popes enjoyed following the death of prelates, which allowed them to confiscate property. Among these lists of books we are lucky enough to be able to recognise the library of Antonio degli Orsi, bishop of Fiesole (1301–10) and therefore of Florence, who died in July 1321 and was buried in a beautiful walled grave, sculpted by Tino di Camaino, in Santa Maria del Fiore. The bishop stars in a novella in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (VI 3) where, along with the Catalan Dego della Ratta, he is on the receiving end of a cutting jibe from Nonna dei’ Pulci, who succeeds in getting even with the bishop after he had made a joke at her expense. It was during the era of Antonio degli Orsi, in 1319, that Albertino Mussato travelled from Padua to Tuscany to ask for help on behalf of his city against the military oppression of Cangrande della Scala; the historian and poet fell ill in Siena, and was therefore taken to Florence to be treated by the doctor Dino del Garbo in the house of bishop Antonio. Once he was back to full health, he dedicated a short poem in hexameter to the bishop, describing the vision of the afterlife he had during his illness (Pastore Stocchi, Il Somnium; Feo, The Pagan Beyond).

Three lists of the bishop’s manuscripts were committed to paper in a volume in the same collection, MS Collectoriae 414, on fols. 5r and 7r–v, 23r, and 26v–27r: these are respectively the inventory of his property drawn up shortly after his death, the list of books created to gauge the interest of relatives, and finally the list of volumes received by the commissioner Ponzio di Stefano, which includes a valuation of each individual item (Williman, Bibliothèques I, pp. 106–8 no. 322.5; RICABIM 1, pp. 26–7 no. 137–9). Ten years on from the death of Antonio degli Orsi, on 21 January 1334, Ponzio di Stefano was asked to confiscate the property to pay a debt of 5,000 florins due to Pope Clement V as a result of six years of unpaid tithes (the nuncio’s register contains all the relevant documentation). The first list contains eighteen books, the second contains fifteen, and the third, more complete and analytical, contains 28, with a total value of 275 florins. One of the manuscripts belonging to Antonio degli Orsi (no. 5 on the first list, “liber Storiarum corporis Christi”, no. 4 on the second list, “Liber cum officio Corporis Christi”, and no. 11 on the third list “Uno

libro delle Storie di Corpo di Christo chiosate”, “A book of annotated stories of the Body of Christ”) was acquired by his successor at the pulpit in Florence, Francesco Silvestri, who, interestingly, recommended and promoted the worshipping of the body and blood of Christ in the synodal constitutions he issued in August 1327. It is important to note that the judge Francesco da Barberino, Antonio degli Orsi’s confidante within the Florentine curia, is cited in the documentation as one of those who on 10 February 1323 had received a delivery of the property of the deceased bishop. These were predominantly religious books (the Bible, the Song of Songs and the letters of St Paul with glosses, a missal, pontifical books, antiphonaries and sermonaries), as well as books of canon law. Two volumes of interest are a manuscript with an unspecified work by St Bernard and the widely known De claustro animae by Ugo di Fouilloy (Negri, Il De claustro animae).

The library of Antonio degli Orsi’s successor, Francesco Silvestri da Cingoli, bishop of Florence from 1323 until 21 October 1341 (Salvestrini, Silvestri, Francesco), was much more substantial. The fate of his books is tied to another prelate, Tedice Aliotti, bishop of Fiesole, who died in 1335 and whose twenty-nine volumes, mostly legal in content, were confiscated by the apostolic commissioner Giovanni de Pererio in 1339 (Camera Apostolica, MS Collectoriae 244, fols. 8v–10v; Williman, Bibliothèques I, pp. 119–22 no. 335.5A; RICABIM 1, pp. 295–6, no. 1729). Three years later, in 1342, Aliotti’s manuscripts were filed in the monastery of Santa Maria in Florence along with those of the deceased bishop of Florence, Francesco Silvestri, and a shared inventory was drawn up for the two collections (MS Collectoriae 244, fols. 97r–100r; Williman, Bibliothèques I, pp. 122–5 no. 335.5B). A total of seventy-six books are listed here, including the two bishops’ volumes. In both documents (those written in 1339 and 1342), the compiler decided to indicate not only the contents and external characteristics, but also the start of the second leaf and the end of the penultimate one, providing a crucial means of identifying the individual objects. The second of these inventories includes, at number 38, the following item: “Quendam librum intitulatum De teuletelogio, qui inc. in 2° folio || lucida”. This is MS Marc. Lat. VI 167 (3489), an exquisite copy of Ubaldus di Sebastiano of Gubbio’s work Teleutelogio, which includes a letter of dedication to Francesco Silvestri himself (entry 4). The bishop of Florence’s books placed in the Badia Fiorentina monastery by commissioner Giovanni de Pereiro had been listed in a separate inven-

tory dated 30 April 1342 upon their delivery (Collectoriae, 244, fols. 57v–64v; Williman, Bibliothèques I, pp. 151–3 no. 341.7; RICABIM 1, p. 53 no. 299–300). This additional list, which comprises forty-eight volumes and allows Aliotti’s volumes to be distinguished from those owned by da Cingoli recorded on the other shared list, is, however, less accurate in its description of the individual items, in many cases only recording the incipit; for example, Ubaldus of Gubbio’s Teleutelogio (here no. 17) is simply presented as: “1 librum qui inc. ‘Liber de teleutelogio’”. The events of the manuscripts in 14th-century episcopal libraries are often complex, as we have seen, with the stories of various collections becoming interwoven with the processes of ecclesiastical succession and the right of the curia to confiscate property. It is interesting to note that in March 1341 the cives of Florence involved in the various stages of delivering the manuscripts of the bishops Francesco Silvestri and Tedice Aliotti included Iohannes Villani, the famous chronicler, who arranged for nineteen manuscripts to be sent to Pisa to be combined with those of Dino da Radicofani, archbishop of Pisa, who died in 1348, and which were then in turn confiscated through right of spoil and finally ended up in the Collegio Gregoriano in Bologna in 1371 (Williman, Bibliothèques I, nos. 348.85 and 373.5; RICABIM 1, pp. 195–6 no. 1729).

As you would expect, Francesco Silvestri da Cingoli’s library contained liturgical, hagiographic and legal books. Two tomes worth mentioning are a volume containing Augustine’s De civitate Dei and another listed as “antique littere” containing the Dialogues of Pope Gregory I. There was just one classic in the collection: De re militari by Vegetius, the extremely popular handbook on the art of warfare written between the 4th and 5th century (Shrader, A Handlist; Reeve, The Transmission). The other volume that apparently contained an ancient text, “quendam librum Senece glosatum, qui inc. in 2° fol. || nius” (Williman, Bibliothèques I, p. 125 no. 335.5B 71) or “Senecam De 4 virtutibus, cum aliquibus apostillis” (ibid., p. 152 no. 341.7 29), actually held Martin of Braga’s work De quatuor virtutibus, which was circulated in the Middle Ages with a spurious attribution to Seneca. Dante himself cites this handbook to the virtues in Conv. (Banquet) III 8 12 and Mon. II 5 3, in the latter attributing the work explicitly to Seneca. marco petoletti

bibliography: Williman, Bibliothèques I, pp. 119–25 no. 335.5, pp. 151–3 no. 341.7; RICABIM 1, p. 53 no. 299–300, pp. 295–6, no. 1729.

Vatican City, Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, Camera Apostolica, Collectoriae 244, fol. 99r.

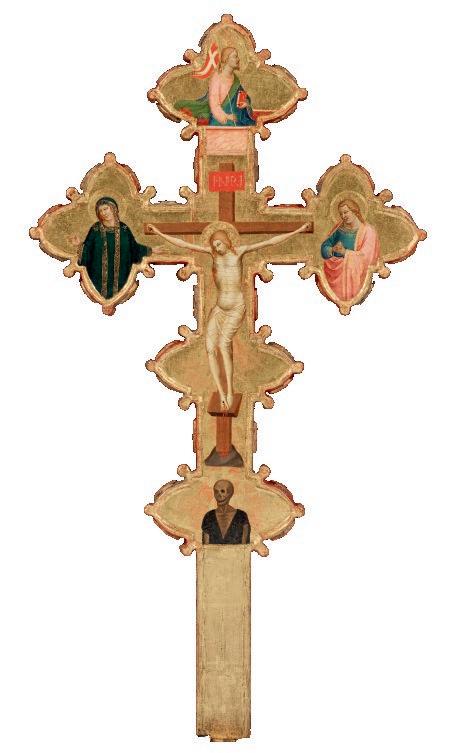

6. Bernardo Daddi, Processional Cross

Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, inv. 3195

Florence, c. 1340

Panel,cm 58,9 × 33

riga riga

The cross, grafted onto a modern pole, was subject to a detailed morphological analysis and restoration by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in 2003–4 (Ciatti, Croce). The painted surface is in good overall condition.

This precious and remarkable item was created by Bernardo Daddi, as recognised back in 1911 by Bernard Berenson (communication reported by Antonio Muñoz in Pièce; Berenson, Pitture italiane). Richard Offner (Corpus III/3; Corpus III/4), the author of the most comprehensive discussion on this artist, excluded the work from the extremely limited number – just 19 – that he considered to be fully autograph works, instead attributing it to an artist’s “close following”, although later critics have reinstated it into Bernardo Daddi’s corpus. The cross was given the same attribution in the new edition of the Corpus (Offner–Boskovits, Corpus III/4), accompanied by a suggested date of the mid-1340s, due to similarities with Daddi’s very late paintings (the artist died in the plague epidemic of 1348). All other critical studies, however, suggest an earlier date, somewhere in the middle of the previous decade. This is the view of Andrea Di Lorenzo, who conducted a meticulous analysis of the painting based on historical considerations and supported by comparisons with works with known dates, such as the tabernacles currently located in Edinburgh (National Gallery of Scotland, inv. 1904, dated 1338) and London (Courtauld Institute of Art, inv. P.1978. PG.81.1, dated 1338; Di Lorenzo, Croce astìle, p. 21). Compared to these works, the figures on the Milanese cross generally have less slender, more solid forms, and the outlines, and therefore the drapery of the garments, are highly simplified. Although these characteristics can, at least in part, be explained by the destination and function of the work, a date of around 1340 is nevertheless the hypothesis that best accounts for its formal characteristics.

The cross, which is painted on both sides, has attracted the attention of critics not only as a fine example of Daddi’s work, but also due to its unusual iconography. The main side shows Jesus on the cross, in between the mourning Virgin Mary and St John, who are positioned in the trilobes at the ends of his outstretched arms; above, meanwhile, there is a less common depiction of Christ rising from the tomb, while below, in the place typically reserved for Adam’s skull, is the bust of a corpse,

provenance: Rome, collection of count Grigory Sergeevich Stroganov (1829–1910); sold at auction as part of this collection in 1925 (Galleria d’Arte). It was later added to the collection of the Florence-based antiques merchant

with the head already reduced to a skeleton, covered by an open-chested and sleeveless tunic. On the other side, the trilobes at the end of the cross contain three beheaded saints: to Jesus’s right, in the position of honour normally set aside for the Virgin Mary, is St James the Greater, as correctly identified by Andrea Di Lorenzo (Croce astìle, p. 16); John the Baptist, recognisable from the camel hair visible beneath his cloak, is on the left, and Paul the Apostle is at the top, identifiable thanks to his characteristic receding hairline. Two Dominican saints are painted below: St Peter of Verona, with a palm branch identifying him as a martyr, and St Thomas Aquinas, with a book alluding to his Summa theologiae. St Dominic was probably depicted at the centre, in an area that is now lost, to which a brown colour was added during restoration that incongruously enlarges the image of Golgotha on which the cross sits.

The repeated references to the themes of decapitation, death and the salvation of the soul made possible by Christ’s sacrifice led scholars to assume the work was made for a brotherhood that provided support to those condemned to death (Offner–Boskovits, Corpus III/4). This was later confirmed by a precious piece of visual evidence contained within a section of a predella painted by Mariotto di Nardo depicting St Nicholas of Bari Saves Two Innocent Men from Decapitation (Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia, inv. 1890.9206), in which a religious man shows a convict a cross similar in all aspects to the one we are discussing here (Dal Giglio, p. 184 [entry by A. Di Lorenzo]). In Florence, however, there is no record of Dominicans or confraternities connected to them supporting convicts, and the creation of the cross has therefore been linked to the preaching of the Dominican Venturino De Apibus of Bergamo, who in 1335 led a mass pilgrimage to Rome that stopped in Florence, where he preached and gathered new supporters, as noted by Giovanni Villani (New Chronicle, XIII 23; see also Sebregondi, Riti, rituali; Zorzi, Angoscia; Dal Giglio, p. 184 [entry by A. Di Lorenzo]; Piazzoni, De Apibus). The friar, a passionate orator and supporter of extreme penitential practices, was also strongly involved in providing support to those who had received the death penalty, as proven by the founding of the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Morte in Bologna in 1336, and he may also have stirred up the feelings of his supporters on this topic in Florence and the other places he visited

Eugenio Ventura, which was sold in Milan in 1932 (Galleria Scopinich); at this point the work was acquired by the Museo Poldi Pezzoli. For a more detailed account of the histories of the various collections, see Di Lorenzo, in Dal Giglio

on his journey (Benevolo, Confraternita). Leaving aside Venturino’s role in the growing attention being given to the practice of comforting, the iconographic contents of the cross also allow a reasoned hypothesis of the precious item’s original destination. The presence of St James the Greater in the position of honour at Christ’s right, and the inclusion of St Peter of Verona and St Thomas below, suggest a connection with the Dominicans at the Church of Santi Iacopo e Lucia in San Miniato (Pisa). This was one of the minor centres in Tuscany where capital punishment was carried out and, according to a report noted by the sources, but without any documentary evidence, from the 1330s onwards there was a confraternity dedicated to providing comfort to convicts, founded by Riccio Roffia, a member of one of the leading families in San Miniato and potentially even one of those who followed Venturino of Bergamo on his Roman pilgrimage (Patella, Confraternite, p. 257). Unfortunately, news of this brotherhood only becomes more precise from the mid-15th century onwards, when it appears in documents with the name ‘confraternity of the Frustati di San Pietro Martire’. Its members met in an oratory that still exists beneath the current church, built back in 1324 and where, in around 1410, the workshop of the Florence-based artist Lippo d’Andrea painted a cycle of frescoes in terra verde telling the stories of the passion of Christ (Marconcini, Assistenza, pp. 226–33). Here, in the late 1330s, with the strict teachings of the Dominicans echoing around the church, a glimpse of the cross painted by the master Florentine painter may perhaps have provided a final encouragement to repent, or simply offered comfort.

sonia chiodo

bibliography : Pièces, p. 12, tables iv–v; Galleria d’Arte, p. 25; Offner, Corpus III/3, p. 12; Galleria Scopinich, no pag.; Offner, Corpus III/4, pp. 194–5; Berenson, Pitture italiane, p. 144; Offner–Boskovits, Corpus III/4, pp. 382–7; Ciatti, Croce; Di Lorenzo, Croce astìle; Dal Giglio, pp. 182–5 (entry by A. Di Lorenzo).

7. Taddeo Gaddi, Annunciation

Fiesole, Museo Bandini, inv. 22

Florence, 1343–8.

Panel, cm 123,5 × 82,1

riga riga

This panel consists of three poplar boards, originally joined by two crosspieces, traces of which remain on the back. A first-hand analysis of the work shows that the painting retains its original shape and frame. As there are no traces of pegs for joining it to other panels, the work must have always been a single board, refuting the hypothesis put forward by Angelo Tartuferi (in Eredi di Giotto and in L’eredità di Giotto). The painted surface is in a good state of repair, apart from the lower area, where the paint has almost entirely fallen away; some limited repainting can be seen particularly on the figures’ faces and outlines, where the pigment, as it overlaps the gold, is more fragile.

The work has undergone two documented restorations: one for the post-war reopening of the Museo Bandini in 1954 (Florence, Opificio delle Pietre Dure, GR no. 1838) and another in 1989 (Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, U.R. no. 1517), which confirmed the panel’s provenance by bringing to light the coat of arms of the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio in the circular decorations in the upper corners of the frame (Museo Bandini). This was one of the first ‘confraternities of justice’ to be established – secular brotherhoods set up to support those condemned to death and to look after their corpses, with their origins in the spread of penitential and charitable practices during the 14th century, and specifically the teachings of the Dominican friar Venturino of Bergamo in 1335 (Fineschi, Rappresentazione).

The Confraternity of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio was, according to the sources, founded on the eve of the Feast of the Annunciation in 1343 or 1347 and, while initially it is only documented as providing general support, starting in 1356 there are reports of the brothers being involved in burying the corpses of the executed, and as of 1423 the systematic comforting of convicts first in the rooms of the Bargello, then during the procession through the streets of Florence to the gallows, delegated to a restricted number of brothers, known as the Neri (Fineschi, Rappresentazione; Sebregondi, Riti, rituali). In reality, chronicles from the confraternity suggest that some comfort on the night before the execution was being provided before 1423, albeit to a lesser extent (Memoriale, fols. 2r–3v; Di Lorenzo, Croce astìle), as confirmed by the opisthographic panel in this exhibition depicting the Crucifixion of Christ and the Beheading of the Baptist (entry 8).

Taddeo Gaddi’s painting was probably commissioned for the confraternity’s first premises, the oratory built between Via Francesco de’ Macci and

provenance: Confraternity of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio, Florence; documented from 1804 onwards in the Bandini Collection, Oratory of Sant’Ansano, Fiesole; in the Museo Bandini, Fiesole since 1913.

Via al Tempio, the current Via San Giuseppe, near a Marian tabernacle where the brothers would often assemble to worship (Passerini, Storia, p. 483; Uccelli, Lezione, pp. 8–9). Indeed, in this building, before it was even completed and just ahead of the plague of 1348, the brothers installed “una certa dipintura di nostra Donna, alla quale si cominciò una grande divozione” (“a certain painting of our Lady, to whom we have become highly devoted”), which can probably be identified as the Annunciation now in Fiesole, particularly given that the subject it depicts is linked to the day in which the confraternity was formed (Memoriale, fol. 2v).

The first certain evidence of the panel, however, dates from 1755 from Father Giuseppe Richa (Notizie istoriche), who saw a “rather old Annuciation” on the main altar of the church that at the time was the main premises of the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio, in Borgo la Croce. The painting could also match the “ancient painting on board approx. 2 braccia [116 cm] in size depicting the Most Holy Annunciation” acquired in 1786 at an auction of furnishings confiscated from various confraternities by a man named Lorenzo Codacci (Innocenti, Dispersione, p. 377; Sebregondi, Riti, rituali). Codacci may have been an intermediary working on behalf of the canon Angelo Maria Bandini, in whose collection at the oratory of Sant’Ansano in Fiesole the work is documented in 1804 on the right-hand wall of the second bay (Inventario 1804). It has been in its current location, along with the resto of Bandini’s collection, since 1913.

The Virgin Mary’s slightly reticent posture (Luke 1:26–38) perhaps allows us to surmise that the artist knew Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi’s work from 1333, while the depiction of the lily branch held by the archangel Gabriel, and not in a vase at Mary’s feet, is one of the earliest we are aware of, along with those found in some small triptychs by Bernardo Daddi, for example in Altenburg (Lindenau Museum, inv. 15). The choice of iconography was incredibly successful, and was reworked, in some cases multiple times, from the second half of the 14th century onwards, by painters including Pietro Nelli (Oro), the Master of the Misericordia (Chiodo, Corpus IV/9, pp. 266–9, 277–9), an anonymous painter who it has been suggested could be Giovanni Gaddi, the son of Taddeo and Agnolo’s elder brother (Boskovits, Pittura fiorentina, pp. 64–5), Tommaso del Mazza (Deimling–Pasquinucci, Tradition), Lorenzo di Bicci (Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, inv. P15s2) and Lorenzo Monaco (Lorenzo Monaco).

The painting was identified as the work of Taddeo Gaddi by Osvald Sirén (Giottino), although he later downgraded it to a product of Gaddi’s workshop (Giotto), as did the majority of critics from the first half of the 20th century, including Khvoshinsky and Salmi (Pittori toscani), Raimond van Marle (The Development) and Pietro Toesca (Il Trecento); however, Richard Offner (Studies; The Mostra) saw it as an autograph work, while Bernard Berenson (Italian Pictures; Pitture italiane) believed it was predominantly autograph. In 1959, Roberto Longhi (Qualità) reaffirmed the attribution to Taddeo Gaddi, a thesis supported by Alessandro Parronchi (Studi), Pier Paolo Donati (Taddeo Gaddi) and Cristina Bandera Viani (Fiesole). Andrew Ladis (Taddeo Gaddi), the author of the only monograph dedicated to this major figure in 14th-century Florentine painting, attributed it to Gaddi’s workshop, working to a design by the master painter, as well as downgrading some of the painter’s other major works in a similar way. However, this is a minority view among critics – the literature that followed has unanimously recognised it as a finely executed fully autograph work (see, for example, Museo Bandini; Neri Lusanna, Taddeo Gaddi; Oro; Neri Lusanna, Maso; Labriola, Taddeo Gaddi; Lenza, Bandini; Eredi di Giotto; L’eredità di Giotto; Chiodo, Taddeo Gaddi). Turning to its chronology, the information in the chronicles of the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio confirm the 1340s dating indicated by Longhi (Qualità) and in general reiterated by all subsequent critics, with the exception of Parronchi (Studi), who believed that the panel belonged to the upper register of the now lost polyptych of Santissima Annunziata, datable to 1332. The production of the gold leaf also suggests the work dates from the 1340s: compare, for example, the chased floral and acanthus patterns on the halos and along the edge with those of the polyptych at Santa Maria Novella depicting the Virgin and Child Enthroned and Sts Peter, John the Evangelist, John the Baptist and Matthew, created by Bernardo Daddi and dated 1344.

To understand Gaddi’s artistic production from this period, it is essential to recognise the connection in the 1330s and 1340s with the direction Maso di Banco took in his figurative style, particularly the large blocks of solid colour and the simplified yet soft style of the outlines, which produced a highly naturalistic effect (Longhi, Qualità; Neri Lusanna, Taddeo Gaddi; Neri Lusanna, Maso). In the panel from Fiesole this “amicizia mentale” (“mental association”; Longhi, Qualità) is particularly evident in the clarity of the outlines – which are even more striking when

contrasted with the pure gold background – and in the delicate smoothing of the flesh. Giotto’s stamp, meanwhile, remains as strong as ever, not only in the extraordinary power of the work, which is simultaneously solemn and exquisite, but also the simplified reworking of the architectural throne that housed the Virgin Mary in the Adoration of the Magi in the Lower Basilica of St Francis of Assisi, previously depicted more accurately in the Baroncelli Chapel. The Annunciation therefore fits perfectly, as Longhi suggested, between the frescos painted in San Miniato (1341–2), those in Pisa (1342) and the polyptych featuring the Madonna and Child Enthroned and Sts Lawrence, John the Baptist, James the Greater and Stephen, which is now in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 10.97), with which the most convincing comparisons can certainly be made. chiara demaria

bibliography: Richa, Notizie istoriche, II, p. 132; Inventario 1804, no. 6; Rondoni, Inventario, no. 19; Cruttwell, A guide, p. 27; Sirén, Giottino, p. 88; Wehrmann, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 16; Brunori, Catalogo, room II, no. 16; Khvoshinsky–Salmi, Pittori toscani, II, p. 16; Sirén, Giotto, I, p. 268; Kreplin, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 32; Van Marle, The development, III, p. 345; Offner, Studies, p. 64; Berenson, Italian pictures, p. 214; Giglioli, Fiesole, p. 211; Offner, The Mostra, p. 84; Berenson, Pitture italiane, p. 184; Toesca, Il Trecento, p. 622; Longhi, Qualità e industria, p. 39; Parronchi, Studi, pp. 137–8; Donati, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 38; Klesse, Seidenstoffe, p. 293; Bandera Viani, Fiesole, p. 11; Ladis, Taddeo Gaddi, pp. 53, 155; Museo Bandini, pp. 79–82 (entry by M. Scudieri); Skaug, Punch Marks, I, pp. 96–7; Neri Lusanna, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 438; Oro, pp. 26–31 (entry by A. De Marchi); Neri Lusanna, Maso, pp. 41–2; Labriola, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 171; Deimling–Pasquinucci, Tradition, pp. 124, 130, 134, 311, 322; Di Lorenzo, Croce astìle, pp. 16, 28, 41; Sebregondi, Riti, rituali, p. 41; Lorenzo Monaco, pp. 177–8 (entry by G. Freuler); Lenza, Bandini, pp. 22–3; Eredi di Giotto, pp. 18–23 (entry by A. Tartuferi); L’eredità di Giotto, pp. 120–3 (entry by A. Tartuferi); Chiodo, Taddeo Gaddi, p. 119; Brunori, Breve percorso, pp. 53–5.