Foreword

Specialists of differing disciplines view and interpret Chinese furniture variously, based on their respective expertise. The experienced furniture restorer is able to ascertain the type of wood, and probably the time at which the piece was made, by scrutinising its style, workmanship and joinery. He could easily discover the parts that have been repaired. The museum curator and the connoisseur would appreciate its aesthetic quality: the simplicity and elegance of the Ming furniture or the ornateness and stateliness of the Qing furniture. He would look to painting, calligraphy, woodblock prints and other works of art for information, placing the object in a social or cultural context for authentication. On the other hand, the archaeologist would date the piece by comparing it with accompanying burial goods such as ceramic vessels, jade, lacquer wares and other artefacts excavated at the site. Irrespective of their different methodologies, these specialists would often be able to validate the piece from their independent findings.

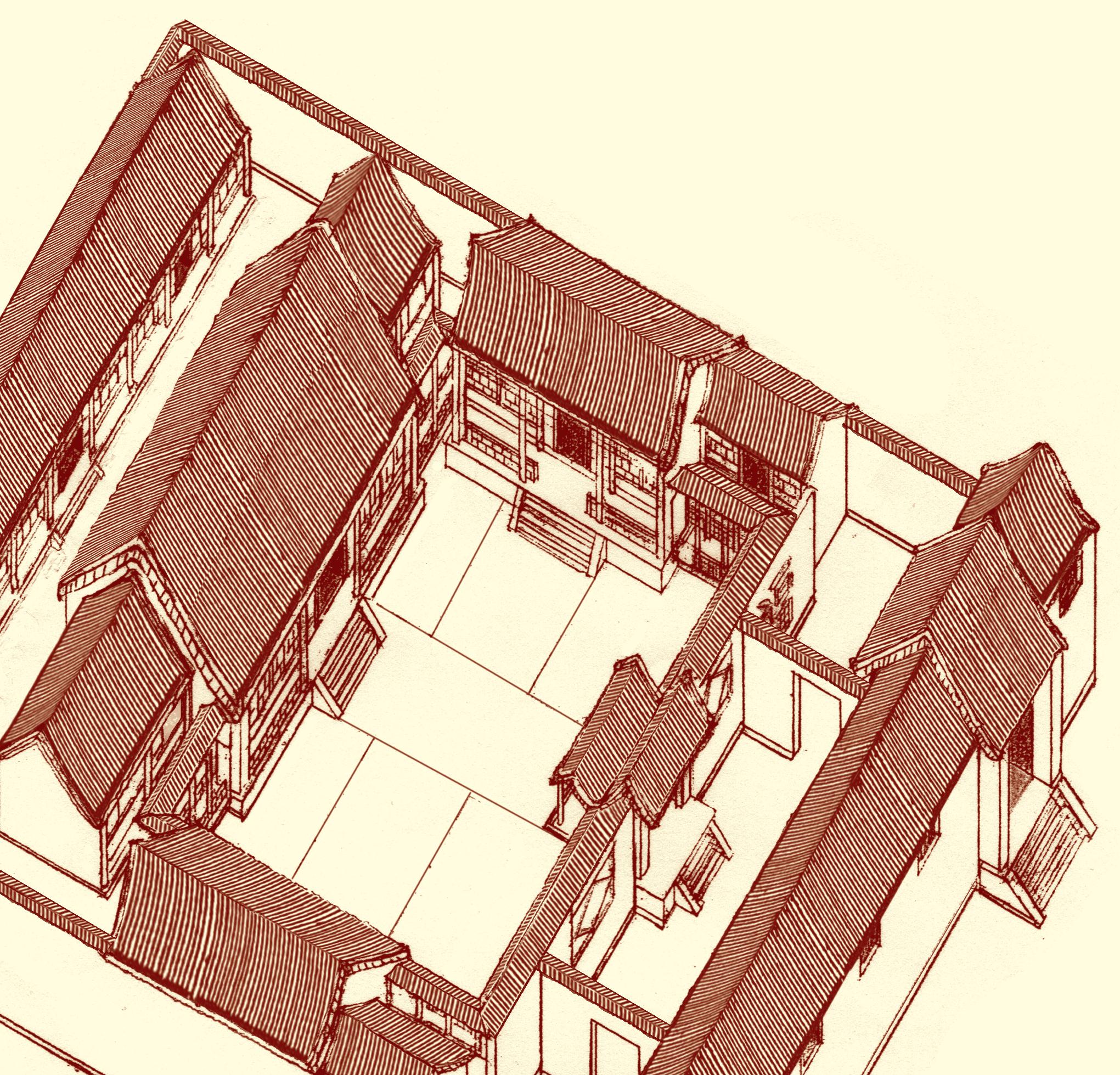

Using information from contemporary sources gathered from these specialists and his study on siheyuan - the closed quadrangle courtyard house - the author has drawn illustrations elucidating the arrangement of Chinese classical furniture in the interiors of this type of habitation in Beijing, putting together a most reader-friendly and accessible book of its kind on the subject.

Chinese wooden building construction and furniture are closely related in terms of structure, design and decoration. In the olden days, carpentry was divided into building construction (damuzuo) and cabinet-making (xiaomuzuo). The former deals with joinery in the construction of wooden structures and houses, and the latter with furniture-making and decoration. Thus, wooden architecture has significantly influenced furniture with respect to design and structure. For example, both the huanghuali recessed-leg table (4) and the huanghuali painting table (5) in the Liang Yi Museum collection have splayed legs joined to the tabletops. They resemble the traditional beam-and-post building structures with splayed or tapered columns. This applies also to the huanghuali round-corner cabinet (13), which has splayed side posts. Such technical devices are used to achieve both structural and visual stability of the pieces. In fact, splayed legs are seen on all chairs, tables and high stands illustrated in this book. This structural design quirk is based on a series of calculations in statics, described in The Engineering Methods and Regulation issued by the Ministry of Work in 1734 during the reign of the Emperor Yongzheng. Furthermore, many decorative motifs and patterns used on furniture could also be seen on contemporary houses. The chi dragons carved on the latticed panels of the eight-panel screen (25) are also found on contemporary architecture. The stylish characters of fu (happiness) and shou (longevity) carved on the latticed panels of the huanghuali six-poster canopy bed (30) are also decorative motifs constantly repeated on architecture of the Qing period.

The general public often holds the opinion that the siheyuan are localised only in and around Beijing. In fact, this type of courtyard house was also very popular in southern China. Sometime ago, my work brought me to Hangzhou where I surveyed more than a hundred courtyard houses of the period ranging from the late Ming dynasty to the early 20th century. In those days, matching his status, financial capability and the number of residents, the owner would commission the building of a single or multiple-courtyard house for comfortable living. The type in Beijing is typically single-storey while those in the south are mostly two-storeys. War, natural calamity and man-made damage through the ages have destroyed many of them. The few remaining are either dilapidated or altered for commercial use as guest houses. Soon siheyuan-courtyard houses with original furnishings will fall into oblivion.

Chinese classical furniture made from the hardwoods huanghuali and zitan represents the zenith in the development of furniture making. Each piece made by the hand of the master cabinet-maker is a timeless work of art. However, the high cost and rarity of the woods limited the quantity of production. Only the elite class of nobility, high officials and landed gentry could afford to custom-make such furnishings for their grand courtyard houses. On the other hand, ju wood furniture from Suzhou and yu wood furniture from Hebei and Shanxi provinces were produced in large quantities. These softwood types formed the bulk of ancient traditional Chinese furniture. Such furniture usually had a decorative lacquered surface. It catered for the commoners living in their modest courtyard houses. Nonetheless hardwood furniture was also made in these and other parts of China.

Notwithstanding protective lacquer coating for the softwood and the inherent durability of the hardwood, traditional ancient wooden furniture have suffered damage and destruction from longstanding wear and tear, misuse, fire and flooding natural and man-made disasters that occur at a sadly regular occurrence, traditional Chinese wooden furniture is fast disappearing. Liang Yi Museum, being a custodian of Chinese antique furniture, has taken on the mission of collecting and preserving this particular type of Chinese cultural property, so as to foster academic research to further the knowledge on the subject. The museum holds regular exhibitions and seminars for the appreciation and enjoyment of the public. In the broader perspective, in spite of its Chinese origin, it is also contributing to preserving part of the universal cultural heritage.

Angela Zhu Collection Manager Liang Yi Museum September, 2016

描述四合院的家具及佈置

Description of Furniture and Arrangment in Siheyuan

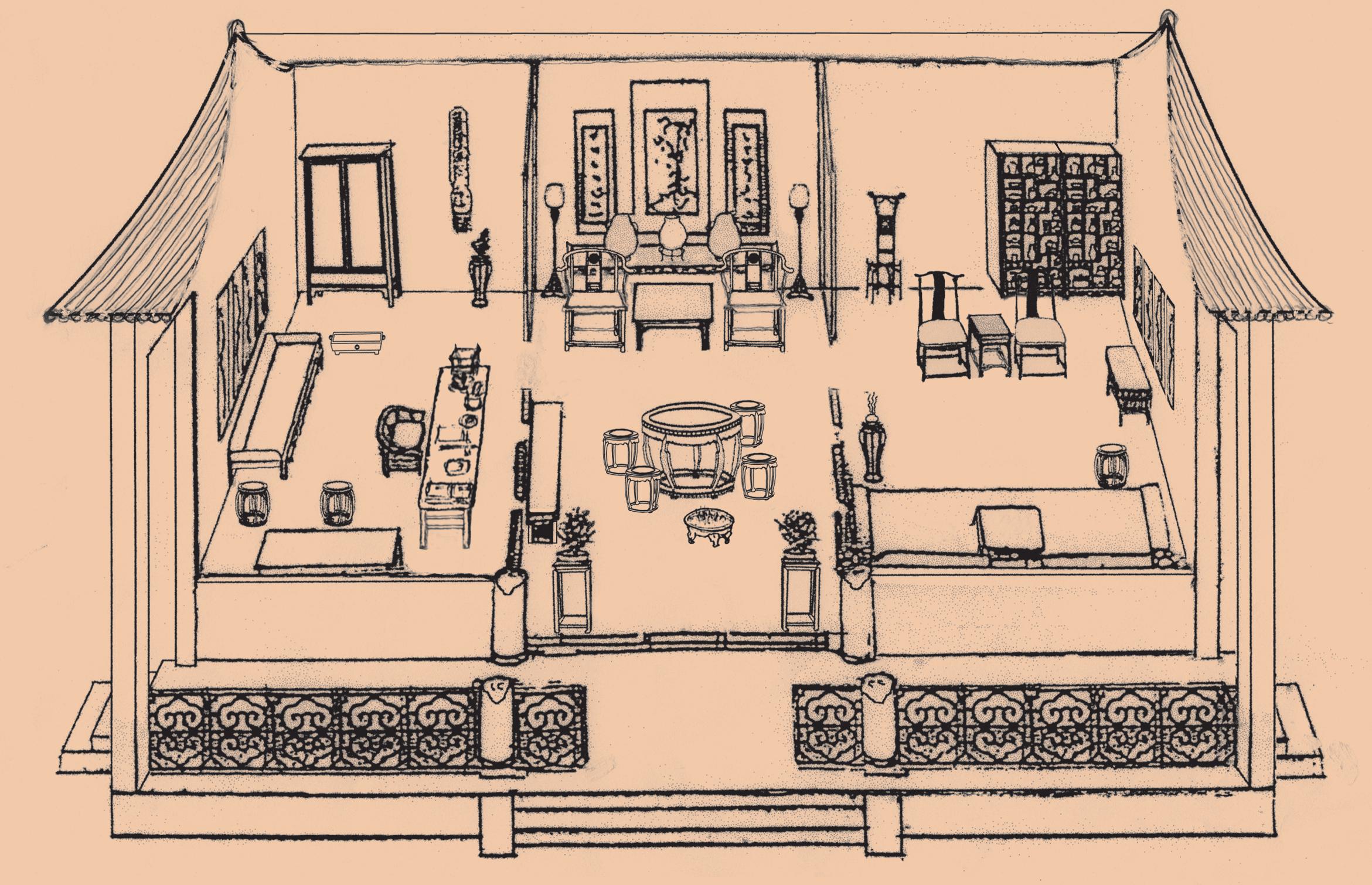

The main hall, various studies, and bedrooms were common elements within the courtyard plan. The furniture made during the Ming and the early Qing periods was used in the interiors. Each was typically arranged with a variety of furnishings.

The main hall was multifunctional and traditionally served both ritual and secular purposes. For special events panelled doors were dismantled to extend the interior to the covered verandah outside and even the central courtyard for activities. The main hall is three-bay or three-jain wide without internal divisions. The jain is the basic module defining the space between four columns. Its central rear wall facing south towards the entrance is the most honorific position. This is where an altar table or a high and long an -table would be placed for important ceremonies as shown in Illustration (4) Apparently this hall had been decorated for the celebration of a parent or grandparent’s birthday. Above the an-table on the wall is a hanging scroll with a large character shou (longevity) in ornate calligraphy. A couplet written with gold ink on red paper flanking the scroll conveys the same auspicious wish. The pair of vases on the an-table with decorations of a hundred deer in famille rose enamel, represents the rebus conveying the wish for abundant wealth. The table screen is for decoration.

正廳、書齋及臥室均是院內基本的建設,房間 佈置都有特別的安排。特殊日子裏,正廳的扇 門都可以拆下來,把室內的空間延續至庭院中 央,以配合各種活動的需要。正廳有三「進」 寬,內部沒有分隔。「進」是四柱間所規範的空 間,後牆面向着入口處是最尊貴的位置,是放 置祭桌或長案,為舉行祭祀及拜祖用。

插圖(4 )展示正廳裝飾成慶祝壽辰的佈置, 在案上方的牆,有華麗的壽字掛軸,其上橫樑 處,鑲上「宏開慈宇」的牌匾。掛軸兩旁有吉 祥意義的金字紅箋對聯,案上一對粉彩百鹿圖 尊,代表富貴之意,還有小插屏的裝飾。

Illustration (4) The main hall of the Kung’s residence at Qufu, Shandong province, decorated for a birthday celebration

插圖(5 )孔宅正廳婚禮佈置

Illustration (5) The main hall of the Kung’s residence, decorated for a marriage celebration

Midway in front of the an -table is a square table with an armchair on either side. Further away, two rows of chairs with low tables between them are placed symmetrically on either side parallel to the central axis. By the two sides of the an-table are two standing lamps stands with red candles. The square table and chairs are all draped with red fabric frontals for the joyous occasion. The interior shows that the side room on the left is similarly furnished. However, the set comprising the antable, a hanging scroll of landscape painting and a couplet, is installed at the east wall instead. Also a square table and two chairs are installed in front of the an-table. However there are no extra rows of chairs and low tables.

Illustration (5) shows similar placement of furniture in another main hall that had been decorated for the celebration of marriage, as signified by the banner hanging above a large painting flanked by a couplet on the panelled wall. The fourcharacter phrase can be translated as “union by divine decree”.

Such layout of furniture in the main hall had been the convention not only in north but also in south China, throughout the Ming, Qing and early Republic periods. Illustration (6) shows this same setting in the main hall Caiyi Tang (綵衣堂) of the Weng Tonghe’s (翁同龢) residence in Jiangsu province (江蘇省)

案前放置一方桌,桌的兩旁設置圈椅,距離圈 椅不遠處,在南北軸的左邊及右邊,排列着兩 行扶手椅,椅間配以小茶几,案的兩旁有紅臘 燭的立燈座。方桌及椅子都套上紅色繡花圍 罩,營造喜慶氣氛。在正廳左面靠牆處也有相 似的佈置:靠牆有案,案的上方有山水畫掛軸 及對聯;案前亦放置方桌;案左右方有椅子。

插圖(5 )展示正廳舉行婚禮的佈置;在北面牆 上掛上山水畫軸,畫旁襯以對聯;牆上近橫樑 處掛着「天作之合」橫額。自明清至民國初年, 無論中國南北方正廳家具的佈置,都遵照這樣 的體制。插圖(6 )展示翁同龢在江蘇省住所內 的正廳「綵衣堂」亦是如此佈置的。

Illustration (6) The interior of the main hall, Caiyitang(綵衣堂)in the residence of Weng Tonghe 翁同龢 (1830-1904), tutor to Emperor Guangxu, in Jiangsu province

東廂房及西廂房 East and West Chambers (Gentlemen’s living quarters)

插圖(8 )三進東廂房鳥瞰圖 麥耀翔繪圖

Illustration (8) Bird’s eye view of the three-bay interior of east chamber. Drawn by Philip Mak

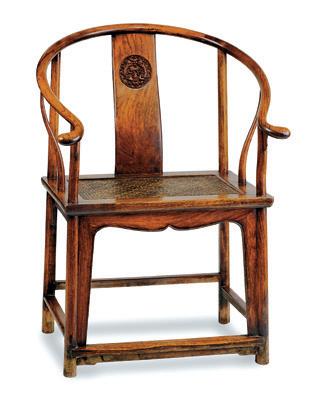

1) Round-back armchairs(圈椅)

4) Long recessed-leg table with everted flanges(翹頭條案)

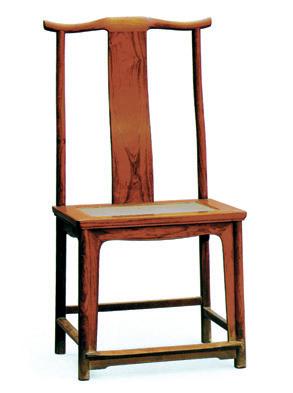

2) Side chairs with projecting crestrail (燈掛椅)

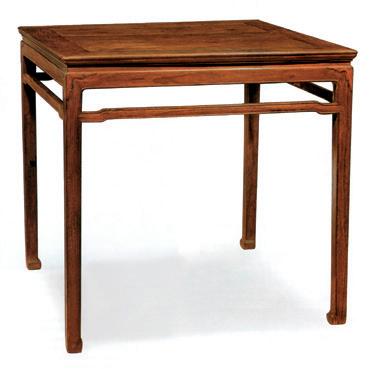

5) Recessed-leg painting table

3) Square table(方桌)

6) Long corner-leg table(條桌)

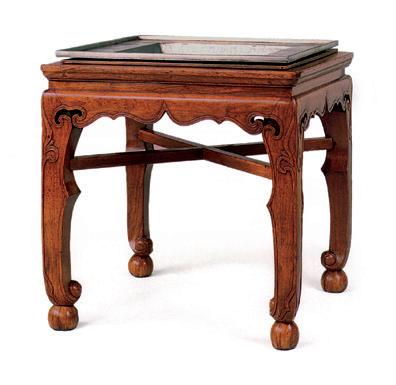

7) High stands(花几)

10) Circular table(圓桌) with drum stools(綉墩)

13) Round-corner cabinet(圓⻆櫃)

16) Lampstands(立燈)

19) Lingbi Rock(靈壁石)

8) Incense stand(香几)

9) Circular stools(綉墩)

12) Three-drawer coffer(聯三櫥) 11) Daybed(羅漢床)

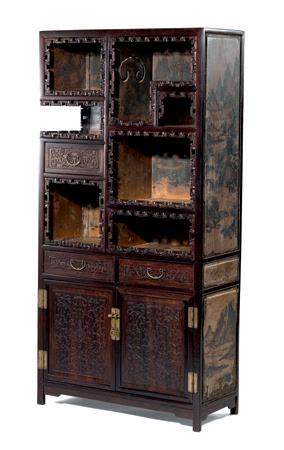

14) Multi-shelf cabinets(多寶格/櫃)

17) Tall washbasin stand(面盆架)

20) Qin(琴)

15) Calligraphic panels(書法掛屏)

18) Brazier(火盆)

註: 本頁小圖的左上角為圖版號碼。

右下角為圖版所在的頁碼。

Note: The number on the left top corner of the thumb – nail images is the plate number. The number at the bottom right corner is the page number where the plate is located

* 四件櫃沒有擺設在插圖(8, 頁 28

* This piece is not shown in illustration (8, p. 28) but for the sake of comprehensiveness, it is included here to show another type of cabinet