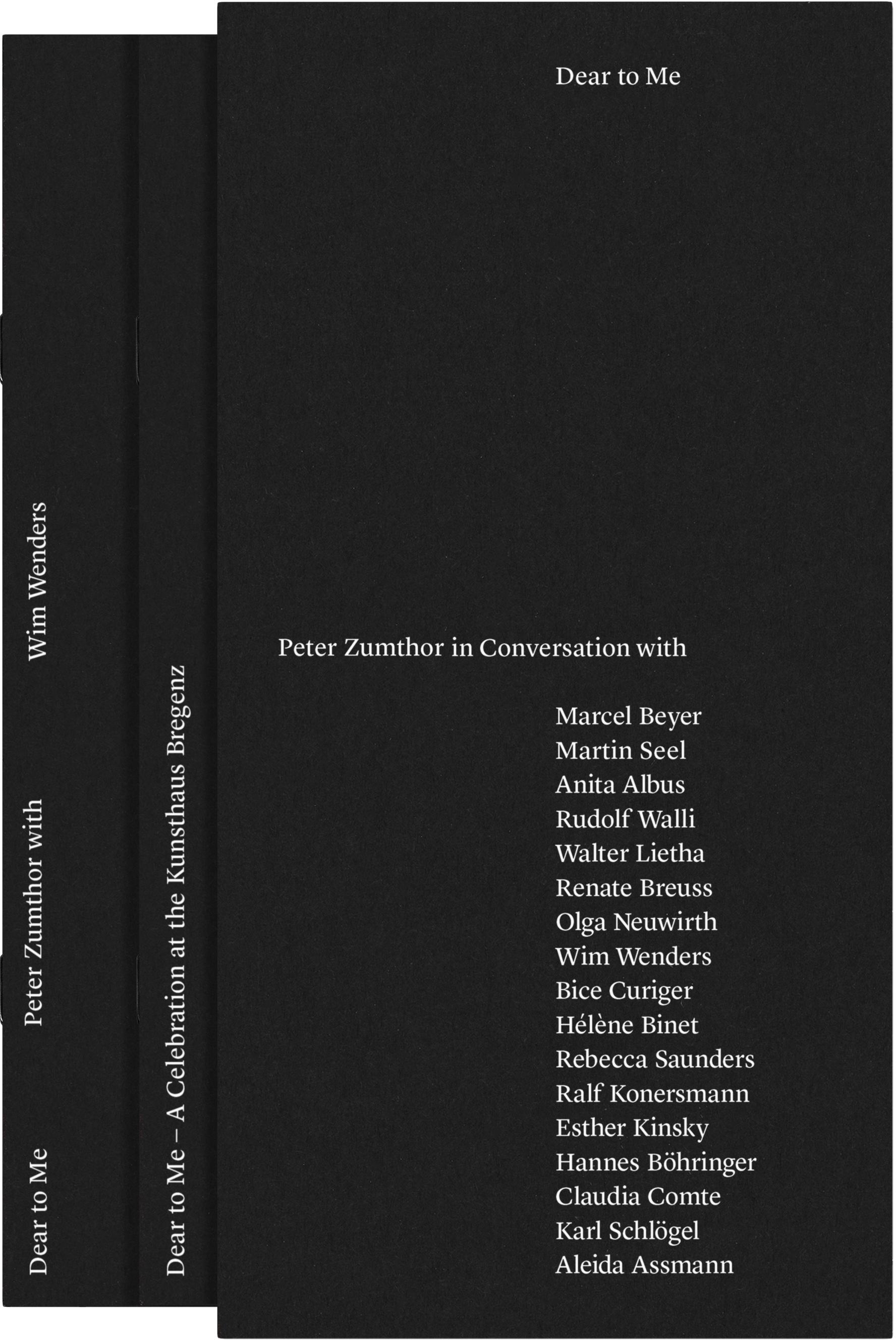

Peter Zumthor in Conversation with

Wim Wenders

Kunsthaus Bregenz, November 12, 2017

Peter zumthor:

Good morning, Wim Wenders. Thank you for coming here today. The picture that first pops into my head when I think of your work is that of a mountain ridge or something like that. To me it looks like a desert with people dancing, moving slowly and rhythmically to the most wonderful music. Was it a sand dune?

Wim Wenders:

The mountain ridge is actually a mound of gravel in the Ruhr Area and what you’re thinking of are Pina Bausch’s dancers toward the end of the film Pina.

Pz: Yes, exactly.

WW:

But you might also have been recalling the sequence from her dance drama Le sacre du printemps from the same film. First the women throng together in a group and then they slowly advance, stomping across a desert of dark peat toward the camera. The beauty that touched you so was at any rate created by Pina Bausch. I was just the tool that made it visible to others who couldn’t be there to experience it live.

Pz:

Well it certainly worked for me, and for many others too. The image was so powerful it burned itself onto my brain, which is why I can call it up again in an instant. Looking at it, I find myself wishing that things were always the way they are in that moment, with people dancing beautifully in a world without war. You seem to love people, is that right?

WW:

Yes, of course, otherwise I wouldn’t be in this profession at all. The beauty of it is that I’m able to make something that exists only when someone sees it. You were a good example of this just now. A film doesn’t exist simply because there are copies of it. In fact it exists only at the instant someone sees it. The scene that you described with the people dancing toward you, this mountain ridge that fragments into figures — I created that moment not on my own, but together with others, and solely so that it would be seen. All art exists only when others receive it. I would even go so far as to say that everything exists only when it is seen or heard.

Pz:

Do you set out to touch people? And if so, why? Perhaps that’s a strange question . . .

WW:

Not at all. May I digress here?

Pz: Please do.

WW:

It took me a while to understand that such a thing is possible at all. As a young man I wanted to become something else entirely, namely a painter. But then I got sidetracked and ended up doing a different kind of painting — painting with the camera. But the greatest thing in the world for me was still the image and my ambition was to put more images into the world. So I was still a painter, only now with the camera. And as a young and inexperienced person working in a new discipline, I did a lot of experimenting, because everything was new and I was learning all the time. And so at some point I began showing two takes, one behind the other. These images were actually just landscapes, cityscapes.

Pz:

You started with landscapes?

WW:

Yes, with moving cityscapes. As I said, I began editing such images one behind the other. Each of them was an image in its own right, but I soon noticed that the order in which I edited them made a difference; and that if I produced four images one after the other and played music to them it became something else again. And so I found out empirically that a sequence of images produces a story, and with time it became clear to me that a story is not the same as a picture. In a story, an image is just one part among many, and it is used solely to narrate something larger.

Pz:

What exactly is a story in this context?

WW:

The German word for story, Geschichte , already has the word Schicht, meaning layer, built into it; hence the notion of the story as something layered. Telling stories was something new for me. It wasn’t something I sought; all that I wanted was to paint pictures. Only gradually did I realize that I could do something else with these images, that I could actually tell a story with them. But storytelling requires not just an I, but also a you. Storytelling is communication. In the course of time I enjoyed it more and more and was willing to just let it happen. And then the first people began to crop up in my work and at some point one of them actually said something, too.

Pz:

So you moved on from silent film . . .

WW:

I had to go through the silent stage first, as it were. Then at some point telling stories became greater, more complex, and more beautiful than merely creating images. I saw that the image in a story is fit for purpose only if it is an element of service to the larger narrative. So I slowly made the shift from image-maker to storyteller, for which I needed someone who would listen to me. After all, stories don’t exist at all if there’s no one there to listen to them. Another leap came when I realized — although this was much later — that image-making is not something that comes

exclusively from me, since I’m also a beneficiary of all the many thousands of film images that were created before me.

Pz:

Are you talking here about intuition or about something that has fallen to you?

WW:

I’m not talking about intuition. I don’t believe in the kind of filmmaking in which one person thinks up everything herself so that everything is of her own invention and turns out exactly as she imagined it. I try to remain open to whatever happens — as when actors start ad-libbing or when the weather does its bit and passing clouds plunge everything into gloom or the sun comes out. The uncontrollability of these things is something I’d like to incorporate into my storytelling; I’ve come to appreciate it more and more over the years and increasingly seek it out. The moment I really understood it was when making a movie that I’m sure you know: Der Himmel über Berlin, which in English is called Wings of Desire.

Pz:

Was that an epiphany for you?

WW:

Hmm, epiphany . . . there’s another word for it that’s rather more abstract . . .

Pz: Intuition?

WW:

No, more like catharsis perhaps.

Pz: I know what you mean.

WW:

Thank you! I’d dreamed up this story about angels roaming the city, although what I really wanted to do was to narrate Berlin. I wanted to narrate Berlin as fully as possible, in all its many aspects, so not just horizontally as the lonely little island it was back then in the mid-1980s, but also vertically through time. I searched desperately for figures that would allow me to narrate this city as comprehensively as possible. That I finally chanced on the city’s angels was thanks to Paul Klee, Rainer Maria Rilke, and

even the Bible. The angels, guardian angels that can move freely through space and time, were ideal characters for me. So that’s how the story about the guardian angel who falls in love with a trapeze artiste came about.

Pz:

I would have fallen in love with her too. (both laugh)

WW:

That doesn’t surprise me. I just thought that an angel couldn’t help but love a human being who flies. But that’s not actually the point I wanted to make. We started that film very spontaneously. There was no script.

Pz:

But I thought Peter Handke wrote parts of it?

WW:

Handke did write a few important monologues and dialogues, but there was no story as such, no plot.

Pz:

There was really no story? How was it, working with Handke?

WW:

I went into it with this blind faith . . .

Pz:

. . . blind faith — that’s great!

WW:

. . . in the power of the city itself and all the places I’d selected for shooting to carry it. What made the film ultimately were the specific places we filmed and the omnipresent angels. It was like writing a poem and starting all over again every day. Here and there I was able to make use of those wonderful texts by Handke — not to advance the story, but more as beacons helping me to navigate a night flight without instruments.

Pz:

I understand.

WW:

But I still haven’t got to the point I wanted to make in answer to your question. We started from scratch and for the first few days we didn’t even have any costumes for the angels. The children we were shooting with at the time took one look at the outfits the two actors were supposed to wear and burst out laughing. In

fact, whenever they found something funny I knew right away it wouldn’t work — all those long flowing robes and cascading tresses or even armor. (everyone laughs) So we sifted through the whole iconographic history of angels — both peaceful and warlike — and at some point arrived at those stupid trench coats, if only because nothing else worked and it was high time we began shooting. Which finally brings me to the point I wanted to make all along: Suddenly I understood what the film was all about, so I turned to my then eighty-year-old cameraman, Henri Alekan, and said: “If we’re going to shoot all over the city with these angels who can see and even understand people,” I said, “then we have to do something with the camera that they themselves can’t do, because these angels don’t look at things the way we do. They look lovingly at the world and the camera has to translate that.”

Poor old Henri was pretty taken aback by that and after a while turned to me incredulously and asked: “And how am I supposed to do that?”

Pz:

That “loving look”?

WW:

Exactly. How was the camera supposed to look lovingly? I told him I didn’t know, but if it didn’t, then we might as well not make the film at all. We would have to teach the camera how to do it. Then I noticed that you can only expect something of a camera if you invest something of yourself in it, too. So the real work facing us was getting the cameraman and the camera operator and everyone else on set to understand that this story would work only if we all learned to film the things and people in front of the camera full of love.

Pz:

What you’re talking about now is not just the camera that films lovingly, right? You wanted to see acting full of love as well.

WW:

Exactly, because of course the camera alone isn’t enough. The actors also had to invest rather more than usual.

Pz:

Bruno Ganz was very good at conveying tenderness. That was a skill he retained right up to his death.

WW:

Yes, absolutely, and perhaps he learned it back then . . . He didn’t just pretend, which after all anyone can do. He actually found the angel somewhere inside himself. But what I really wanted to say was this: If viewers are to experience something as loving, then it first has to be made lovingly, too. But that’s something that can be said of pretty much everything, isn’t it? That there’s a correlation between what you invest and what comes out at the end.

Pz: Yes.

WW:

Which brings us to the relationship between viewers and filmmakers. That was originally your question. I work in the hope that viewers will see not only what I’m filming — the cities, landscapes, people, things — but also the attitude informing it. An attitude as such is invisible, yet it can still be seen and felt.

Pz:

But I still have to ask: How do you do it? You said you wanted to show Berlin in all its facets and in all its depth. That’s you! But what about all the others? How do you get them on board, too — the actors, the camera people, the whole crew in fact? How does that artistic process actually work in practice? Do you, as the author, simply tell everybody what to do? And how do you reconcile that with remaining able to react to other people’s input? You’re very good at it, I know. But how do you do it?

WW:

It works only if I myself am curious and am making a film that enables me to understand something I didn’t know before. The actors have to know that we’re discovering something together and that filmmaking is always a journey. There are those who feel insecure unless everything has been mapped out in advance. But in Wings of Desire I had the great good fortune to be working with people who were willing to embark on the adventure with me. Looking at the film today, I wonder — just like you — how on earth I did it. How was that possible — that letting the unintended happen? There’s no hard and fast formula.

Pz:

Discovering something you didn’t know before is one possible definition of artistic endeavor.

WW:

Right. On the very first day of shooting, for example, Otto Sander, who was a lot more experienced than I was, put me on the spot by asking: “What’s the motivation for me in my role; what’s my biography?” To which I replied: “Angels don’t have one.” (Zumthor laughs) An angel will not have had a difficult childhood, wicked parents, or traumatic experiences of any kind. But biography was Otto’s big thing when filmmaking. He invented his own backstory for each of his roles and then drew on it for his acting. And then suddenly there he was without any biography at all. Bruno was also dismayed at not having any biographical basis on which to work, at least at first, his only brief being to show a kind of tenderness for the mortals he encounters. But he adapted to the situation very well and was almost a bit disappointed when in the course of the film he became a mortal himself. He’d felt very good as an angel, he said.

Pz:

So how did he cope?

WW:

Very well! Otto, on the other hand, wanted to get back down to earth as soon as possible, if only so he could goof around — he was a comedian, after all. But as the story progressed it turned out that Bruno was the one who would become a mortal, whereas Otto would remain an angel. And he was sooo disappointed! (everyone laughs)

Pz:

Thinking back to this film, I’m left with the impression that it’s actually one long poem. There are no episodes, just one long whole.

WW:

Yes, that’s how we made it, too, like a poem. Where it should begin and where it should end was not so obvious. All I had was a pinboard with all those places in Berlin where I imagined — and hoped — the city might crystalize out. Then there was a second pinboard bristling with little cards with possible scenes on them;

and then, finally, a few “islands,” by which I mean the texts by Handke. We were basically flying blindfold and without any controls from one island to the next.

Pz:

So you did have a kind of script?

WW:

Yes, I suppose you could describe those things as a script. But there was something else, too: The plan was to shoot one half, the story of the angels, in black and white, and the other half, the story of Damiel becoming a mortal, in color. Only we had such fun shooting the first of these that we spent almost our entire budget on it.

Pz:

The one in black and white?

WW:

Yes, because it was just so beautiful! That also had to do with Alekan, who had begun his career in the age of silent movies and is one of the great masters of black-and-white film. Shooting with him in black and white was so great that no one really wanted to switch back to color — to return to “real life,” as it were. At some point we realized we’d have to cross that line after all — that was the plan at any rate — and we managed to do it just in time, in the final week of shooting. Bruno quickly became a mortal and we had it in the can.

Pz:

But there are a few dabs of color aren’t there?

WW:

Yes, there are, that’s right. Our working method was in any case dictated by the places where something might take place. What carries the film, ultimately, is the city itself, even if we were not allowed to shoot in the other part — in East Berlin, I mean, despite the fact that Paris, Texas was one of only a handful of West German movies to be screened there — somehow they’d gotten the impression that it was an anti-capitalist film. The problem with Wings of Desire lay elsewhere. East Germany’s film minister was delighted to receive my inquiry and said: “Wonderful! Of course you can shoot over here — wherever you want. Just show me the

script first.” But I had no script and that made him more cautious: “That’s not so easy for us, without a script.”

Pz:

So what happened next?

WW:

I described the angels to him and he found it all very suspect, mainly because they were invisible. “Can they go through walls?” he wanted to know, and when I answered in the affirmative, he asked: “Including through the Wall?” — meaning the Berlin Wall. And when I again answered in the affirmative, he was very blunt: “Herr Wenders, you won’t be able to shoot a single scene here. I won’t let you anywhere near the Brandenburg Gate or the Wall. And don’t come to me with your angels!” (everyone laughs) That’s why we shot everything in the West. Which was a bit of a shame.

Pz:

One more thing I’d like to ask you in this connection: You and I both talk about the advantages of 3 D from time to time, and you’re well on your way to persuading me of its benefits. But when I call to mind Wings of Desire, this abstraction in black and white, I’m no longer so sure whether I myself, as an architect, would want that kind of bold, garish 3D effect. So now I’ve said it. What do you say to that?

WW:

Perhaps not everyone here knows that I would like to make a film about Peter Zumthor and that we’ve both already committed ourselves to this project? In theory we could do it in black and white or in 3 D. I suspect that particular combination has never been done before, though I see no reason why we shouldn’t try. We could certainly abstract the architecture somewhat if we shot it in both black and white and 3D at the same time. Shooting in 3D doesn’t depend on its being in color.

Pz: Has it really never been done before? It could be interesting: on the one hand the abstraction, on the other the enhanced spatiality.

WW:

I’m constantly learning more about this. For me, at least initially, it was spatiality that was 3D’s greatest asset. The film we talked about at the start of this conversation, my dance documentary

about Pina Bausch, was the kind of work that cries out for the spatiality of 3D. Three-dimensionality is simply predestined for dance.

Pz:

That makes complete sense to me, at least in that film and that context. The movements in space are so beautiful, it’s as if they needed it. But we don’t know exactly why this is. Nor am I entirely sure whether architecture isn’t perhaps less in need of such spatiality.

WW:

Yes, you may be right about that. But I think architecture at least has a similar affinity. In Pina Bausch’s case it was obvious, given that the kingdom of dance is space. Conventional film is a twodimensional image sequence projected onto a screen in which space is only ever an assertion, although with a bit of camera trickery it can still generate an illusion of space. Cinema lives from creating illusions, after all. Using conventional methods, the dancers in my film would have been moving only in an imaginary space. To get the viewers inside that space I just had to have 3D. But that was a completely new technique when I first began work on the project back in 2008. We shot with antediluvian prototypes simply because that was all there was at the time. This was before the release of Avatar.

Pz: Back to architecture . . .

WW:

Yes, architecture. I’m now going to talk only about your buildings, Peter. Before setting foot in them — the Bruder-Klaus-Kapelle, say, or the Kunsthaus Bregenz — I first looked at photos of them and read texts describing them. Yet physically entering them for the first time was still a special moment for me; it was as if I’d had no prior knowledge of them at all. Here at the Kunsthaus, for example, I can see how the light changes from one story to the next, and how visitors really are at liberty to look at the works exhibited here. You have this wonderful capacity to create architecture that redefines the whole purpose of architecture. I know of few museums in which visitors can concentrate on the art as intensely as they can here.

Entering the museum here in Bregenz and walking around in it, I understand that you’re showing me what a museum actually is. That’s why I thought it would be good to take viewers with me and enable them to experience this, too. And obviously that will work better if they’re able to enter the space with me. On top of all that there’s the concrete experience of the third dimension inside the movie theater. A 3 D film takes you out of your seat and into a space. The screen disappears and becomes a window, and the three-dimensional image makes the figures a much more powerful presence. They are simply “more there” and the viewer feels “more among them.” And it is precisely that aspect that I find so important in your buildings. That’s why we’re going to shoot the film in black and white and 3D — hopefully very soon. At least we both know how and when we arrived at this idea.

Pz:

(laughs) Exactly! It was on November 12, 2017, at 11.30 a.m. on a Sunday morning.

WW:

And we have witnesses who can demand their money back if the film turns out to be in color after all. Or only in two dimensions. (everyone laughs)

Pz:

I’d like to dig a little deeper at this point: Just now you said something to the effect that films are present not on the screen, but in our hearts. In other words we’re touched by them — or not. Architecture, however, has a presence of its own. It’s not just an illusion. And there is this yearning, which I share, for architecture that touches us. It does happen from time to time and it is not abstract. So perhaps the 3 D would be “responsible” for the touching and the black and white for the abstraction.

WW:

We’re now very close to what we want to do! Of course architecture has an existence of its own much more than does music, say, or painting, or film. It’s more objective in that it conditions us in a rather different way. It creates conditions that enable us to experience things or even to inhabit them. Music and art always remain in us, whereas architecture I can touch. And there is no concrete

more beautiful than yours! That’s why I just had to touch the walls when climbing the stairs just now.

Pz:

May I introduce a different image here? Paris, Texas is a movie I last saw many years ago; but several images from it have remained with me and continue to haunt me to this day. I see a desert landscape somewhere in America; I see a person and I hear a melody. Recalling the film, it is as if the music and landscape had merged into a coherent whole. Is the film a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, in which you work with all the arts — including with architecture, music, and so on?

WW:

In the course of time I discovered that painting is something that is limited to itself, and that with film I could put out feelers in the direction of music, architecture, drama, poetry, and psychology. In Paris, Texas especially, this interaction was a great experience. I knew more or less from the start that the guitarist Ry Cooder could produce those bottleneck guitar sounds that conjure up monumental associations even while retaining a certain airiness and permeability. The beauty of film music is its capacity to unlock the film for you, as long as it doesn’t smother it.

Pz:

Yes, indeed!

WW:

Back then Cooder had never done film music before. But he’d read how Miles Davis did the music for Elevator to the Gallows by standing with his trumpet in front of the screen of a large movie theater and improvising — over and over again until it was right, down to the last note. And Cooder, who can’t even read music — not that that’s anything to be ashamed of — told me that he wanted to do it just like that. So we found an old movie theater in Los Angeles, set up the recording equipment, and he then began to play in front of the screen on which the movie was playing. In those days there was only film — we didn’t have any digital copies to work with.

Pz:

So the scenes were already there and the movie was finished, or almost finished?

WW:

The editing was all done, although when I heard Cooder play and saw the film playing to his music I had the feeling he was essentially shooting it all over again with his guitar; it was as if the guitar itself were a kind of recording instrument. The music turns on a single theme, which is basically just three chords from “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” — an old Good Friday hymn from England that the blues guitarist Blind Willie Johnson riffed on in the 1920s. Cooder did the music for the whole film using just those simple harmonies — improvising, experimenting, and starting over, again and again, until he was completely happy with it. So he practically . . .

Pz:

. . . wrote the soundtrack?

Not just that. He also . . .

Pz:

. . . transformed it?

WW:

WW:

I’d say he took the film somewhere else entirely. Together with his music it went to a completely different place.

Pz:

This reminds me of something. If we happen to be grappling with a problem at my studio in Haldenstein, I often suggest that we first build a large model of the landscape or the neighborhood, because then the design is actually quite easy. I can well imagine that it was much the same for Cooder, sitting in front of your scenes and sensing an affinity with them, finding the right feeling for what he was looking at.

WW:

I also suspect that he imagined his way into the landscapes of the West and then tried to literally sound them out. Big Bend is a National Park in the desert on the border with Mexico and is the hottest part of Texas — and of America, in fact. It’s completely dry there and it was around 50° Celsius at the time we were shooting. People from Mexico have always crossed the border into America in this utterly arid desert region. Our hero appears out of nowhere and wanders back in search of his old life.

Pz:

In my conversation with the composer Olga Neuwirth last week I learned how Miles Davis produced that typically muted trumpet sound of his. Knowing the instrument well, she was able to explain it to me. Apparently he held the mute very close to the microphone and so was able to generate an incredible intimacy even with very few notes. I was reminded of that just now when you described how Cooder recorded the music.

WW:

He did it with a slide guitar, which is traditionally played with a glass slide on the finger. We just snapped the neck off a bottle and he slipped it onto his finger. But the sound was too cold, he felt, which is why he began experimenting with other materials, most of them metal, and eventually ended up using a ballpoint pen — a weird-looking thing that he’d dug up somewhere. That changed the sound and made the metallic twang of the slide guitar much warmer. He messed around with the sound for ages until it was exactly right.

Pz:

Your talk of a “warmer” sound immediately calls to mind Buena Vista Social Club. That whole film is just one great sound and has a tremendous warmth to it.

WW:

Yes, in this case the warmth was the unconditional love of those elderly gentlemen for a music that in fact was long since gone and forgotten. Down and out. No one in Cuba gave a fig about Son anymore. But they played it anyway, and they were indulged and every now and then gave a little concert. All of them were musicians who had played abroad, but who had always come back — who never emigrated, in other words. Whereas many Cuban musicians went to Spain, Florida, and California, they always said: “We belong to Cuba, this is the only place we can live.” The film’s warmth reflects the fact that these people were wholly at one with themselves and with what they were doing, and firmly convinced that it was valuable and worth preserving. And Rubén Gonzàles didn’t even have a piano at home! That’s why he was so eager to go to the studio every morning — because of the grand piano there! When he found out the film crew were going to be

there an hour earlier than usual to prepare the lighting, he naturally got up an hour earlier and wanted to be let in, too. These old gents played with so much passion because for them it was their whole life. They also realized that the film was a chance . . .

Pz: . . . to get noticed.

WW:

Exactly! And that it might even spark a trend. We had to shoot practically twenty-four hours a day, to shoot until we dropped, because once they started playing there was no stopping them.

Pz:

We get a good sense of that in the film.

WW:

They played constantly and were actually offended when we had to stop them briefly to change the cassette: “Don’t you like us anymore or how come you’re not shooting?” But actually the whole thing started completely differently.

Pz:

Yes, that would interest me. How did you get onto this?

WW:

Well Ry Cooder had this project . . .

Pz:

Ah, him again!

WW:

Yes, he already knew the musicians, so it was all his doing. He was the one who brought this music back to life. He asked me to come along with the camera and gave me three days in which to get set up. He introduced us to each other along the lines of: “This is my friend Wim with his German crew and they’re now going to film what we’re recording.” So there we were in this studio and the Cubans were a bit shy at first: “What, they want to film while we’re playing?” Music is something sacred to them, after all. That’s why everyone was so tense to start with. Then we had our first lunch break. Lunch was in any case a problem as finding enough food for everybody — for all the musicians and the film crew — was not easy. There simply wasn’t that much to be had — a bit of rice, a few beans, and some chicken, maybe. Somehow we managed to put something on the table. The film crew and the

musicians then went off into the lobby and Jörg Wittwer, my cameraman, unbuckled his heavy Steadicam and without thinking reached for the bass that was lying there.

Pz:

You mean the double-bass?

WW:

Yes! It had a bow, too, so off he went, playing a Bach sonata without a care in the world, just to relieve the pressure of shooting all day long. Orlando “Cachaíto” López, the owner of the instrument, heard it on the loudspeakers we’d forgotten to switch off and came storming back into the studio: “What’s going on with my bass?” And then the other musicians came back, too. But Jörg just played on as if nothing was happening, and the Cubans just listened with something almost like reverence. That really broke the ice. They saw that the people making the film could play music too. So from then we could do what we liked — and they could do what they liked. Cachaíto wanted to know what it feels like to wear a Steadicam, so Jörg strapped him into it and clipped on the camera at the front, whereupon Cachaíto keeled over because he could no longer stand upright.

Pz: It must weigh a ton!

WW:

You bet! You have to lean back against it with your whole body. Jörg showed Cachaíto how to do it and you can see that in the movie, too — Jörg with all this gear dancing around them. That impressed the musicians no end. They saw that it’s actually just as difficult as making music.

Pz:

Have you remained friends since then?

WW:

We were very close. And for a while we went along with them to lots of their concerts.

Pz:

And how is it now?

WW:

Most of them have since died. Obviously if you work with people who are already eighty and over, you’re not going to be friends for ever.

Pz:

Then we’d better hurry up with my film! (everyone laughs)

WW:

But you’ve a way to go before you turn eighty. Compay Segundo was the oldest; he was already ninety when the film was released. Two years later I was back in Havana and stayed at the same hotel. I went up to my room and there was this bouquet of roses waiting for me. I thought at first it was a mistake, but the man at reception was quite emphatic: “No, Mr. Wenders, the bouquet is for you.” I’d never received roses in my whole life! And in Havana of all places it was nothing short of crazy. Then I found a note. It was from Compay Segundo and said: “Thank you, Wim, I’m having the time of my life.” He was already ninety-two by then. So, Peter, we’ve got plenty of time for that film of ours.

Pz:

We’ve been talking about it for ten years. But in theory we’re getting better at it. (everyone laughs) No, everything’s fine, as far as I’m concerned.

Let’s change the subject and talk about something that has long preoccupied me, about places and landscapes. I love places because I imagine them to be repositories of history — of history or memories of work, of individual fates that we no longer know anything about, and of things that happened there long before our time. Can you make anything of this?

WW:

We two work almost like brothers. Many of my stories are developed out of a specific place.

Pz:

Like Berlin, as you explained to us a few minutes ago. How many places have there been? Seven?

WW:

Oh more than that. Many of my films have titles that contain place names. Wings of Desire is called Himmel über Berlin in German, then there’s Palermo Shooting and Lisbon Story. Place is always important to me, even the Australian desert in Until the End of the World . I always try to find a story that can play only in that particular place, and it has to grow out of that place, too. So to that extent you’re right, places are indeed repositories of history

and of stories. Like you, I believe that places know us well, that they see people come and go, and that they sometimes have to suffer being exploited and plundered and the very worst of what we humans can do. That a certain stock of memories belongs to a certain place, and that this place then becomes the catalyst for a story — that is something I’m firmly convinced of.

Pz:

What kind of places do you like?

WW:

I have an affinity for port cities; I also like desert locations, so places that are empty. Then again I also like places that are full, like cities. Big cities as we know them today arose almost in parallel to the invention of cinema.

Pz:

Because of electricity?

WW:

With electricity came the light bulb and with the light bulb came cinema. Cinema was an urban art right from the start; that’s why I like cities. But I also love their opposite: places that are utterly desolate. I’d so much hoped that you would build a hotel in the Atacama Desert. Then we could have started shooting much sooner . . . (laughs)

Pz:

Well yes, only my client suddenly found a new friend from the Harvard Business School and after that it was all over with that project. That’s just the way it is sometimes. (laughs) I have the feeling that the places you love are not so much monuments as places that are slightly melancholy, perhaps a bit run-down or neglected. Or am I mistaken about this?

WW:

I’m always deeply touched on discovering a place that has been spurned. The American Friend, for example, we shot in Hamburg in a part of town that was about to be torn down, or so we were told. Cinema has this wonderful capacity to capture and conserve — and astonishingly, movies almost seem to do this better than documentary films. The moment a story is set somewhere specific, the location is conserved and can demonstrate its full potential far more powerfully than it could in a documentary

film. Because stories have the power to “conserve.” One of the my favorite cities is San Francisco and the greatest movie ever set there, in my view, is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. A movie that conserves, even exalts, San Francisco better than Vertigo is impossible to imagine. Yet it is pure fiction — and ridiculous fiction too. But that doesn’t matter, because the story is rooted in this one city. My love of Japan also comes from movies — those of my favorite director, Yasujiro Ozu, who filmed almost exclusively in Tokyo. Thanks to him, when I arrived in Tokyo for the first time I already felt at home there.

Pz:

That’s something I can understand very well. I’ve experienced something similar. I believe I’ve learned most about architecture from films. I could tell whole stories about how a kitchen or an apartment in Paris looks or looked in this or that decade — a whole repertoire, as it were.

WW:

But you remember them precisely because of the story that played there.

Pz:

Yes. My own history is also a story of the films I’ve seen.

WW:

You also make places that are conducive to storytelling or places where people feel at home.

Pz:

Sometimes I think that film directors — not all of them, but some of them, like you — understand more about architecture than many of us architects. They understand the importance of atmosphere. I love that!

WW:

All the films of Michelangelo Antonioni, for example . . .

Pz:

Yes, indeed. Fantastic! In closing I’d like to return to our origins. As a young man you had dreams and began painting, and through painting discovered the world of filmmaking. We also talked about the layers in stories and about history, which is why I’d like to ask: Where do you stand today in relation to the young man you once were?

Over the past few years, my wife and I — Donata is a photographer — have built up a foundation for all my films; because the films will outlive us, just as your buildings will outlive you. So I wanted to ensure that they were no longer dependent on me, but would belong only to themselves and hence to “everyone.” Under the foundation’s auspices we’ve begun restoring them and have done eighteen of the important ones to date, although there are plenty more still to do. This work has brought me face to face with how I started out as a young man. I had the great good fortune to be able to make my first movie at the age of twenty-four, and I’ve added another one every year since then. That was a huge privilege back in the 1970s, and would be inconceivable today. And because I’ve been involved in restoring those early films of mine, those first road movies, I’ve also been able to rediscover the man who made them. The aim when restoring a film is actually just to return it to its original beauty so that it once again looks as good as new.

So now I’ve been making films for over fifty years. In some cases I wonder what on earth I was thinking of and can scarcely remember how a particular work came about — or how, exactly, it was made. Sometimes I think I wouldn’t be able to do that kind of thing today, that I’ve lost something along the way. There are definitely things in my oeuvre that no longer really matter to me; but there’s one thing that undoubtedly endures: All the devotion I lavished on my films — I’m going to use a very big word here — all the love I invested in them has remained. In fact it’s all that has remained. Everything else has fallen victim to the ravages of time. That’s something I notice in other people’s works, too, incidentally. If something is steeped in devotion and if its creator really gave it his all, pouring into it everything he once was or had, then it will endure. It’s shocking how much of our work is no longer of any value at the end of the day. But where love was invested, the value of the work endures.

Pz:

Which is certainly true of yours. Thank you so much for this conversation.