Preface

My attachment to the city of Barcelona began as an architectural student, visiting the city for the first time in 1964. A number of visits over the following years served to reinforce an increasing admiration for its many cultural, environmental, and political changes, but it was to be almost fifty years after my first visit that I had the opportunity to examine the city in real detail. This was the result of an Urban Exchange initiative between the Government of the City of Barcelona, and the Government of Hong Kong in 2012, which I directed over a three-year period. The purpose of the exercise was to develop co-operation in the fields of urban design, development, and revitalization, and to promote the exchange of knowledge and experience through collaboration between Barcelona Regional and three professional organizations in Hong Kong. The alliance between the two cities located on different sides of the globe was intended as a means of examining and resolving urban issues and meeting the aspirations of their respective communities.

It was toward the end of this period that I chanced on an academic paper about a Barrio Chino or Chinatown situated in the heart of Barcelona, that purported to be an established location in a rapidly regenerating part of the city. This caused some degree of bemusement as I had never previously come across such a place but on further enquiry it was not difficult to find the reason why—quite simply, it did not exist, at least not as a cultural entity, nor had it ever existed. It was, in fact, the result of an imaginative reference by a journalist for a newspaper El Escándalo in 1925 who used the term in a somewhat derogatory way by describing the negative physical and social features associated with part of Barcelona’s Fifth District—El Raval. The subject of Barrio Chino subsequently continued to be raised in equally melodramatic terms, and eventually began to resonate with progressive urban thinkers as the city began to experience a long process of regeneration.

A Book of Introduction

Valentina Monturial - Song

This volume of events and recollections represent what we might call a metanarrative. It is in fact based on a series of diaries, miscellaneous stories, and drawings through a very personal interpretation of events that commenced long ago in Canton, China. Collectively, they contribute to a pattern of experience, meaning, and knowledge that make up a picture of Barcelona through space and time. And these experiences are individualized because this illustrious sequence of diarists are compiled by my most immediate ancestors commencing with a resourceful great grandfather to whom we owe our Barcelona domicile, the resourceful Napier Song. My other equally resourceful great grandfather played a prominent part in our family history, but it is to my Chinese ancestry that this book is primarily dedicated. Collectively we represent a long line of architects and city makers, although I should state at the very beginning that I write as an architectural historian and a lover of the city rather than as a practitioner.

I suppose my family have all shared three basic things in common—firstly, a propensity toward expressing strong opinions; secondly, a limitless capacity to visually represent our borrowed city in pencil, ink, or any other medium that comes to hand; and thirdly, a domestic attachment to what became known as the Barrio Chino in the heart of Barcelona’s El Raval District.

One of the popular features of Barcelona is that it is visually comprehensible as a key to projecting its essential identity. Specific vantage points from the waterfront to the mountains chosen by artists, engravers, and photographers tend to reflect the multifaceted complexity of the city by rendering it “readable.” But there are always “spaces of otherness” that remain partly hidden and tell their own story. No single perspective can claim to be the only one. There is often an underlying tension between the conceptual notion of the public realm, and the experience of the actual user that cannot be adequately captured by photographic images. The interpretation of use and

The Book of Favorable Fortune

My name is Napier Song. I am Chinese but live, somewhat incongruously, in Barcelona. The year is 1846 and I have a part-time job in a factory to supplement my weekly remuneration as an architectural assistant. I am learning to speak and write in Catalan, which my persuasive teacher says is a “Western Romance” language named after the medieval Principality of Catalonia. This evidently means it comes from the same romantic family as Spanish.

Song is a transliteration of my Chinese family name 宋. It is also the name of a Chinese dynasty that lasted for more than 300 years from 960 when the country was divided into two parts, and which came to an end only after Kublai Khan was proclaimed emperor reunifying the country. Its first capital was in northern China, but my grandfather used to tell us that the Song court had retreated south of the Yangtze and was the first to establish a navy to defend its waters and conduct maritime missions. What I especially liked about our dynastic family name was that it was known for the spread of literature and knowledge, and the enhancement of this by woodblock printing.

My teacher tells me that writing things down is the easiest means of recalling events, even if some bits of it are in Chinese, and others are in English and Spanish. I should state that this is the beginning of a diary, but what it will cover and where it will lead I will leave to the ever-benevolent god of building Lo Pan, a real life architectural master from the Zhou Dynasty, and what I hope will be a continuing line of my descendants. My less than expected journey begins in 1834 in a village outside Canton, well beyong imperial control, but increasingly shaped by new trading routes where market functions overlapped with local economic and social organization.

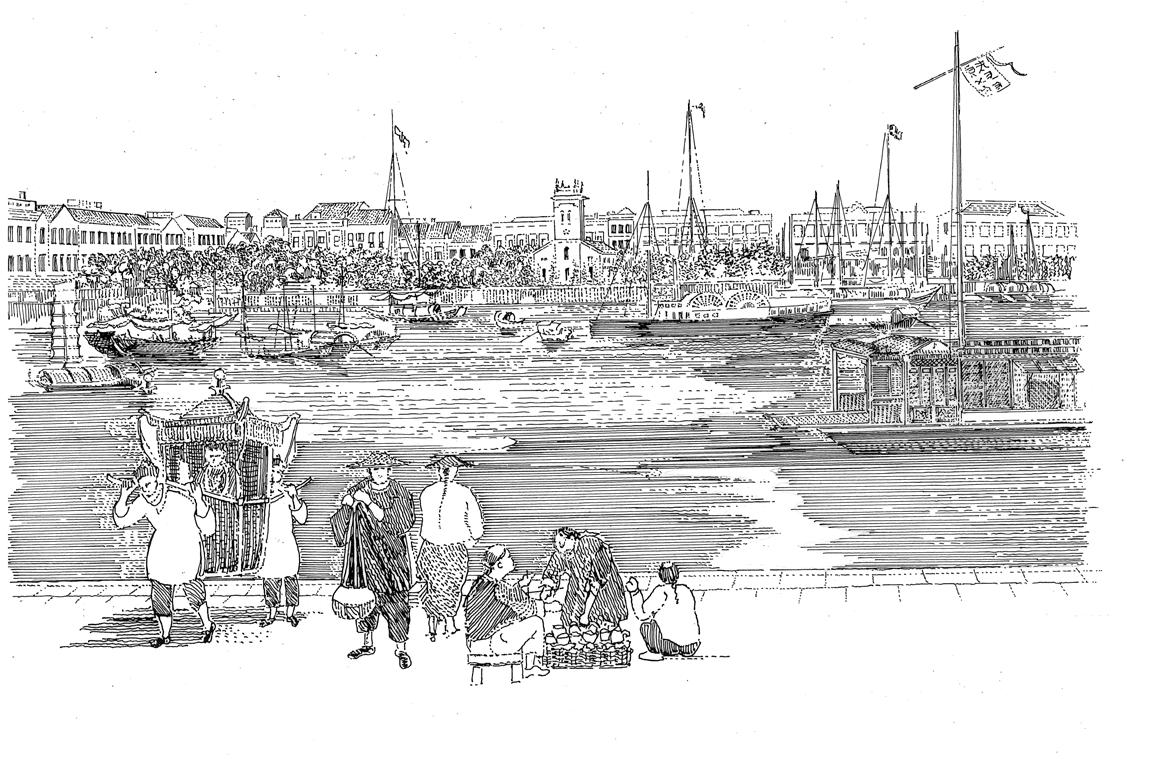

British merchants came to China in the late seventeenth century, encouraged by the East India Company, to submit a request for formal trading representation, and later setting up trading establishments in the Liwan District of Canton. Here they established the first foreign settlement along the Pearl River south of the old walled

the Qing government demanded that all foreigners leave Canton for Macau after the trading season, where they grew steadily more impatient and hostile. Under the Qing Dynasty, ruled by Manchus, foreigners were cautiously welcomed as “tributaries” bringing with them gifts for the emperor in return for somewhat elusive trading advantages. Gradually traders negotiated terms of access to a number of ports, but Canton was the most convenient, carefully regulated by the “hoppo,” the superintendent of customs, responsible for managing trade and collecting customs duties. The Spanish sent a number of ships every year, and their captains were popular as they arrived with large volumes of silver bullion from Mexico via Manila.

The Hongs were granted a lucrative monopoly of foreign trade, and collectively belonged to a guild known as the Cohong, which formed an exclusive and tight-knit group of merchants who monopolized the foreign trade, paying little heed to Peking. This meant regularly slipping taels of silver into the pockets of the splendidly attired hoppo, whose principal job was to prevent smuggling. Of course it was a common but probably mistaken assumption that the significant duties imposed on traded goods were swiftly and discreetly shuttled north to the imperial household in Peking.

conditions gave rise to a constant series of epidemics including outbreaks of typhoid and cholera. Wages were low and job security virtually non-existent. Social reformers were thin on the ground in Barcelona and utopian socialism of the type practiced around the same time by Robert Owen in Wales or Titus Salt in England who endeavored to improve the health and well-being of the working class, were unheard of.

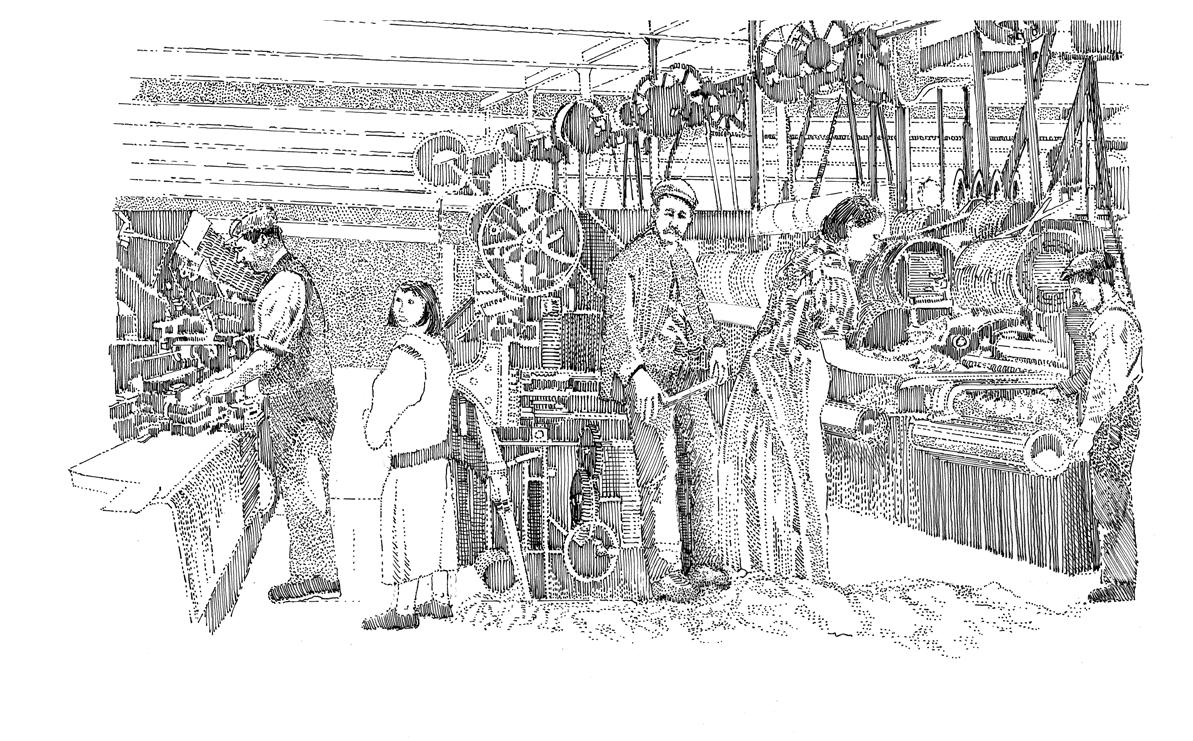

Almost 200 people worked in our factory, including around thirty children. The manually operated machinery was primitive having been imported cheaply from Northern Europe. It was also dangerous to use. Factory work was hazardous and dangerous parts were not screened off. It was not too hard in a sleepy moment to catch a sleeve in a machine and lose a finger or even a hand. Young workers often had to reach over and around operating machinery or even climb on the machines to tie loose threads together, and children were often made to crawl under the machines to retrieve loose balls of cotton. As if all of this was not bad enough, raw cotton is highly flammable and the friction of constantly moving machinery and timber floors could ignite and form firetraps from which there was little means of escape.

protected anatomy, sheathed in black stockings, and periodically lifting their skirts to vacuous applause, squeals of delight and a trembling of waxed moustaches from the fashionable male guests, particularly when time came for the inevitable strip-tease. Around the corner was the Barcelona Circus with animal acts that mesmerized the young Picasso and featured in some of his early drawings.

I occasionally used to visit the Teatre Arnau with some of my boisterous office friends to watch Paca Morqués López—the stage name of an Aragonese singer Raquel Meller—the most famous of all the singers and dancers, interpreting the music of Jose Padilla. Everyone adored her. It is said that she made the chains on your heart loosen. She certainly did that for me. Afterwards we would all go to the Casa Almirall on the Carrer de Joaquin Costa, known not only for its excellent absinthe and exquisite interiors expressed through marble, woodwork, and mirrors, but for its generous sofas suitable for companionable intimacy, thankfully replacing the old wine barrels that had been the original feature.

The Book of Inventive Amusements

The years between 1888 and 1929 effectively gave birth to the modern Barcelona in terms of technological innovation and construction. In the closing years of the nineteenth century, Barcelona began to dabble with various electric technologies. The rapid expansion of power plants was a result of new turbine technology with many companies operating hydroelectric concessions, which lowered costs. A number of international subsidiary companies were also established in Barcelona after the end of World War One, but electric power took second place to gas for heating and cooking. The progressive refinement of operational ability was inextricably linked to an informal relationship between engineers, physicists, entrepreneurs, and the actual consumers. In this sense, the evolution of an electrical cityscape was closely attuned to the role of international exhibition and amusement parks that combined to show off the use of electric lighting for dramatic effect. The first major use of electricity was at the Universal Exhibition in 1888 where thousands of Edison lamps and arc lamps lit up the Ciutadella site, its magic fountain and its approach channels, and made a strong impact on the wider urban structure including La Rambla.

This continued to shape the developing city with new infrastructure, scientific discovery, and forms of energy that powered industry. It also generated a massively increased labor force as the population grew to around one million inhabitants. The profile of Catalan nationalism rose through this period leading to new institutions and research centers responding to emerging fields of knowledge production. All this impacted on the developing cultural disposition of the city as it became transformed through popular science, and transmitted via international exhibitions, museums, libraries, amusement parks, and botanical gardens. Urban space took on symbolic dimensions, incubating new practices and shaping new sites of production just as it also accommodated the desolate back door quarters, hidden from wider public view. This gives credence and memorable association to urban settings and the means by which they were appropriated for whatever length of time by different groups.

and a dystopian counter version of squalor and uncertainty. This seemed also to extend to a physical dimension of difference between the elegant realm of street, square, and garden, and an almost surreal narrative of decomposition and demolition that eroded the relationship between the city’s sense of place and the affinity of its users. Its most memorable buildings were being periodically extracted from the urban landscape; the experience being a little like having one’s teeth removed one by one, and suddenly being unable to eat. With this comes confusion. Militant Marxists, anarchists, and republicans, Barcelona’s famous “three sins,” along with disenchanted outbreaks from working class movements, emerged from corners of the old city and universities to attend secret meetings in secure premises, and then silently disappeared from view out of fear of being swiftly apprehended and beaten by the police.

Long privations and insecurity had made ordinary workers disillusioned and fatalistic, but alert to the possibility that as fascism was in the process of being defeated in Europe, release from dictatorship could not be too far away. However, whatever optimism existed was quickly seen to be misplaced as repressed, hardened, and aggrieved

OPPOSITE

The Book of Elaboration

A number of writers and artists have, over the years, reflected on the changing physical articulation of Barcelona within the framework of the Renaixaença and the approach to a new representation of the city in terms of its spatial transformation and the documentation of “disappearance.” This includes the gradual mutation of the old city through a combination of private speculation and induced urban reforms. It has been largely influenced by the hegemony of industrialization, particularly after demolition of the medieval walls in 1854, and Cerda’s blueprint for urban expansion in the context of Barcelona’s Modernisme as a defining agent of city growth with its radical values and beliefs stemming from the European Enlightenment. Almost inadvertently, this has acted to induce a symbolic and ongoing confrontation between a re-emerging Catalan nationalism and the Spanish government in Madrid.

What has been termed the modern Barcelona model has evolved over fifty years through a series of urban projects that have ranged in size from small interventions in the older city fabric, to parks, promenades, and beachfronts together with major railway, airport, expressway, and port infrastructure. The redirection of Barcelona in the post-Franco period has encompassed a process fostered largely around reconstruction and regeneration. The Olympic Games in 1992 reinvented the city’s identity through an urban spectacle, which provided the essential catalyst for a transformation of the urban morphology through the early 1980s and ’90s, while the Forum of Cultures in 2004 was to have a more strategic impact on modernization over the following decade. As continued regeneration of the city has been extended to its urban fringe and peripheral districts, the planning emphasis is now focused on the changing identity of the city in an age of multiculturalism, with the right to housing uppermost in the face of the city’s determined competitiveness in the global economy and its new strata of interventions.

My immediate and illustrious ancestors have all been, at least to some extent, flâneurs who observed but also lived and breathed the city and its many heterotopic

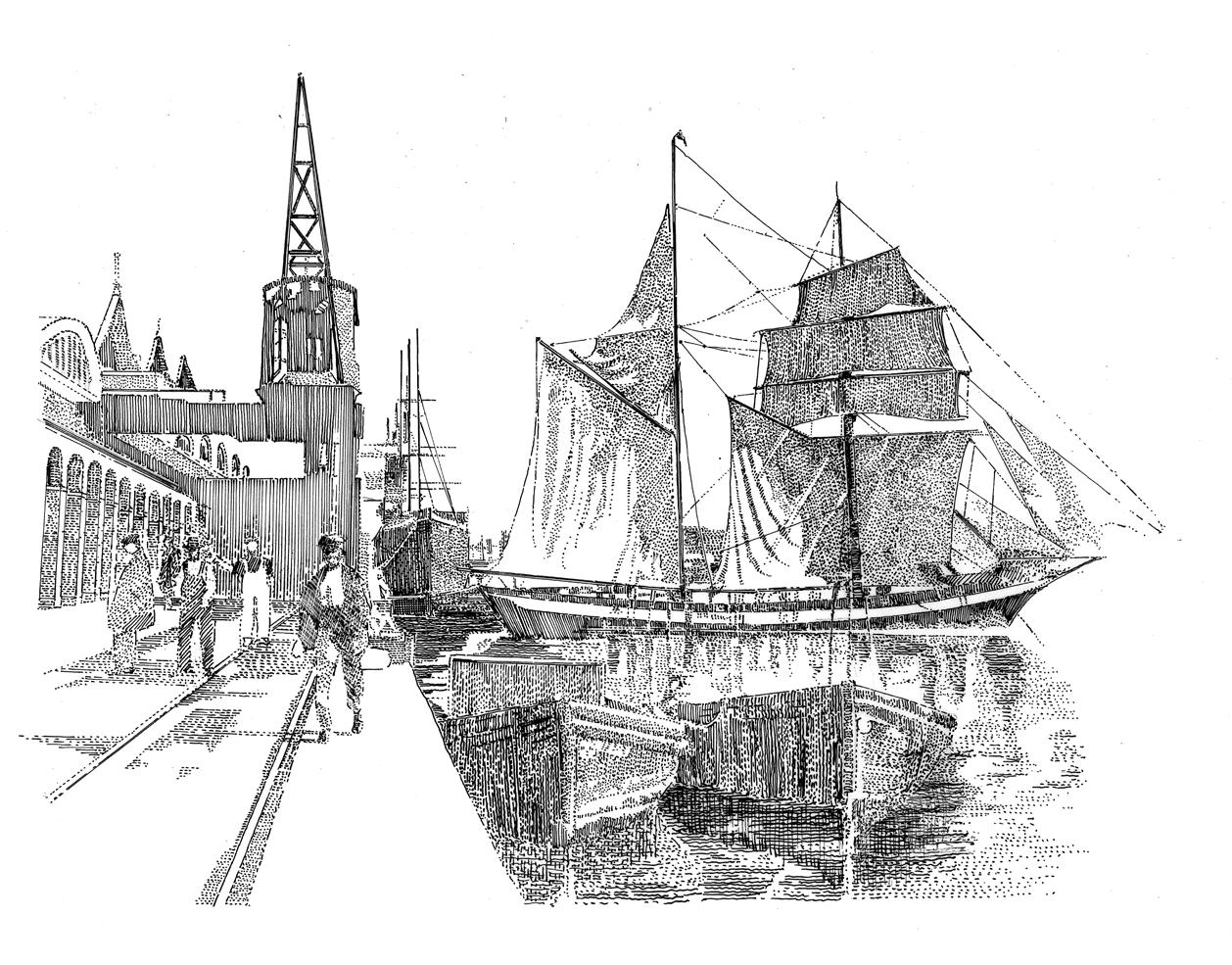

Port Vell built on reclaimed land, accommodates buildings that relate to the city’s maritime and commercial past, now integrated into a new waterfront landscape.

ABOVE

references. Marked increases in property prices suggest that negative associations and representations have been largely bypassed through its evolving narratives of new urban places, its mix of uses, and proximity to the city’s key symbolic destinations.

In my narrow street the spatial experience is temporal rather than visual. I still awake to the daily operating rhythms of the Barrio—the morning opening of grocery and coffee shops, the delivery vans, and the chatter, fragmented and layered on one another so that they add up to a sensual totality. Later in the day comes the more provocative noise of building work, the mix of languages and dialects from locals and visitors, and the pavement cafés whose enticing aromas mix with those of bakeries, wine bars, and more exotic variances. In the evening, the area becomes more personal through subdued sounds and voices echoing through the street behind blinds and from open windows, occasionally aggravated by raised tempers, music, and football commentaries. Rarely does one rhythm dominate another. What emerges is the overall tone and timetable of the community, neither dominating nor competing. The lived experience comes down to the emotional attachment and appreciation on the part of different social groups toward evolving patterns of cultural use and the often-contradictory meanings they instill.

And it is with the Barrio Chino that this duality achieves a subtle poignancy, as reconstruction and realignments have changed its grimy face and undercurrents of association, even if the past aspects of contrast were often indistinguishable amidst the meanness of crime and exploitation. But the Barrio of course represented more than that. It was the focus of an informal economy where its underground black markets and organized crime fed the most questionable of habits, although these were at least counterbalanced by the amalgam of supporting services such as clinics, midwives, and surgeries. The area served a wide neighborhood including the temporary clientele of the port, which generated an inexhaustible supply of speculative customers for the indelicate delights offered by the bars and brothels, and the discreet availability of the brown sticky resin from Morocco they call hashish.

I once read in a book by Jaume Vicens i Vives—Noticias de Cataluña that without Barcelona, Catalonians would lack a crucible in which to blend their hopes, and a pedestal on which to raise their culture. Cities can be the key to liberation or repression, their evolving geography and political machinations creating their own trajectories of enlightenment and opportunity, power and transgression. Highly regulated urbanization is a comfortable phenomenon that broadly falls within the modern age of urban refinement, management, and order without the heterotopia that steers us toward abnormality. On this basis alone it is difficult to oppose the valorizing process of regeneration when it is sensitively applied, even to alienating places.

OPPOSITE

Twenty-first-century Barcelona has a thriving Chinese diaspora, by no means geographically restricted to the gentrified Barrio Chino that continues to change and reinvent its physical characteristics to correspond with a more commodified and visitor-focused city. Approximately 62 percent of Barcelona’s population were born

Canaletes Fountain incorporated with four lamps and decorated with the Barcelona Coat of Arms. It was designed by Pere Falques and installed on La Rambla in 1892.

The Mercat dels Encants on Plaça Glories is the biggest antique market in the city, situated under a massive, mirrored roof.