Preface

Acknowledgments

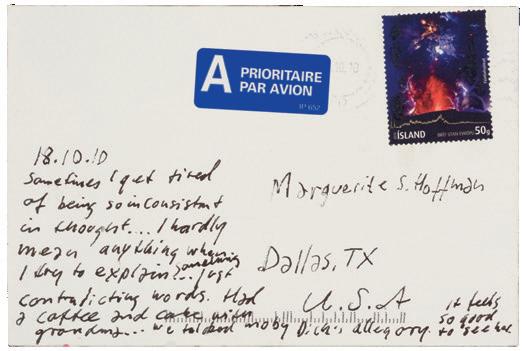

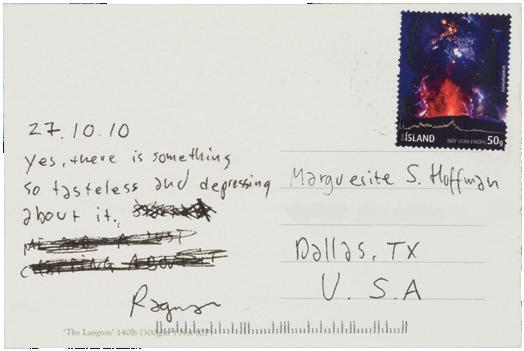

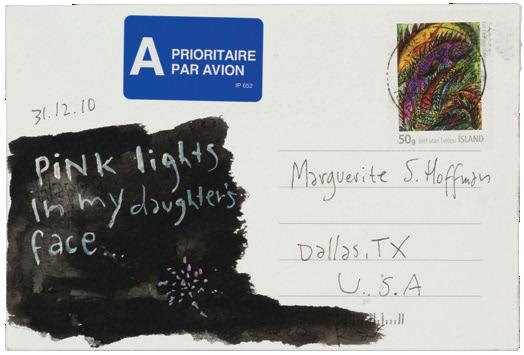

Marguerite Steed Hoffman

Amor Mundi

Gavin Delahunty

Nairy Baghramian by Gavin Delahunty

Lynda Benglis by Kirsten Swenson

Joseph Beuys by Mark Rosenthal

Louise Bourgeois by Nic Nicosia

Mark Bradford by Anna Katherine Brodbeck

Marcel Broodthaers by Raphaela Simon

Miriam Cahn by Dana Schutz

Gillian Carnegie by Barry Schwabsky

Leonora Carrington by Susan Aberth

Richard Diebenkorn by Sarah C. Bancroft

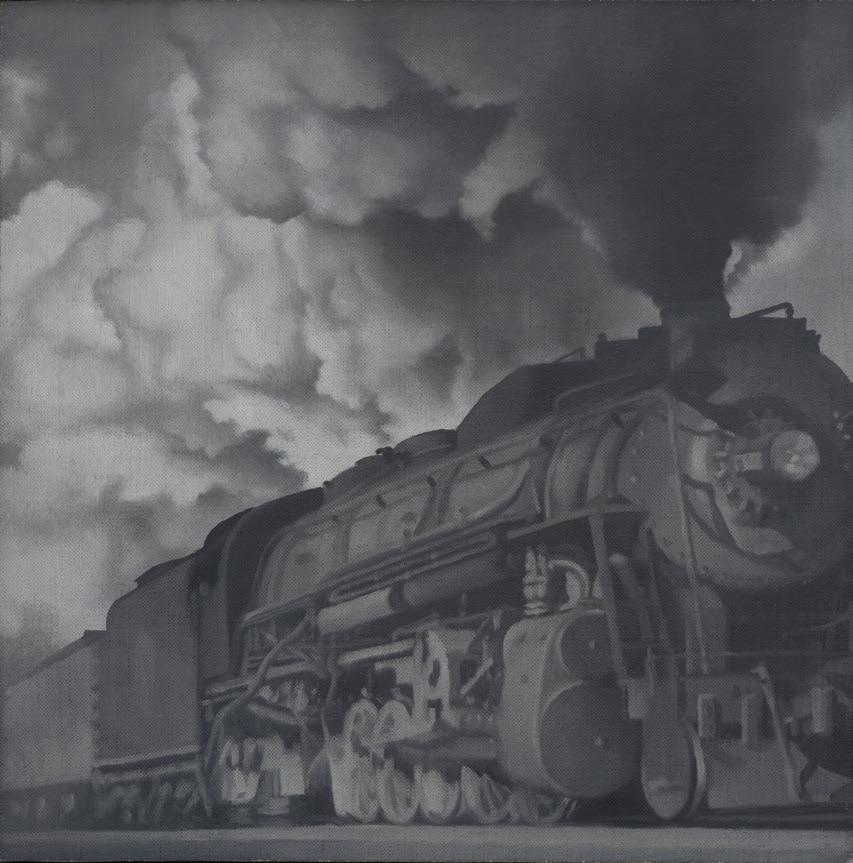

Peter Doig by Richard Shiff

Trisha Donnelly by Anna Lovatt

Ellen Gallagher by Leora Maltz-Leca

Philip Guston by Rachel Haidu

Eva Hesse by Wyatt Kahn

Jasper Johns by Mark Rosenthal

Donald Judd by Richard Shiff

Alex Katz by Merlin James

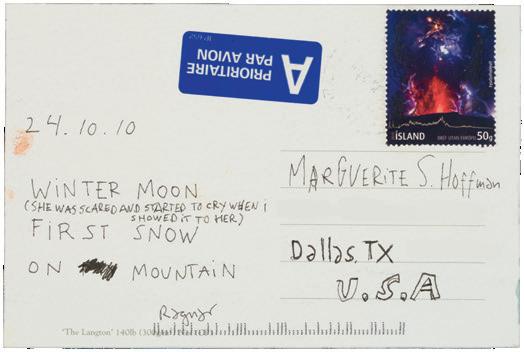

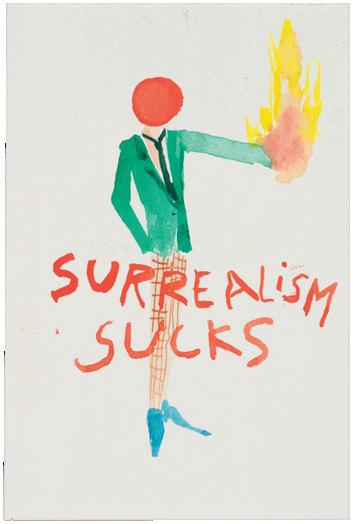

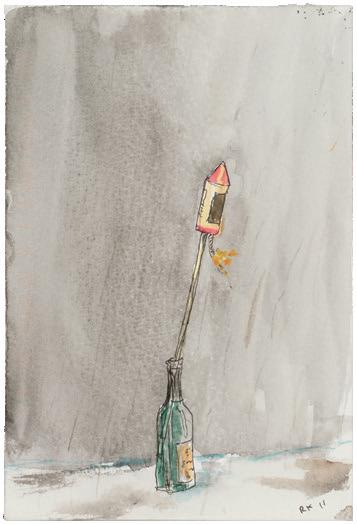

Martin Kippenberger by Ragnar Kjartansson

Vivienne Koorland by Tamar Garb

Someone Saves Something or Someone Somehow…

Renée Green

Endnotes

Timeline

List of Works

Index

Photo Credits

Contributors

Mementoes Post-Mori:

Thoughts on the Collector’s Mania

Martin Jay

Martin Jay in conversation with Marguerite Hoffman

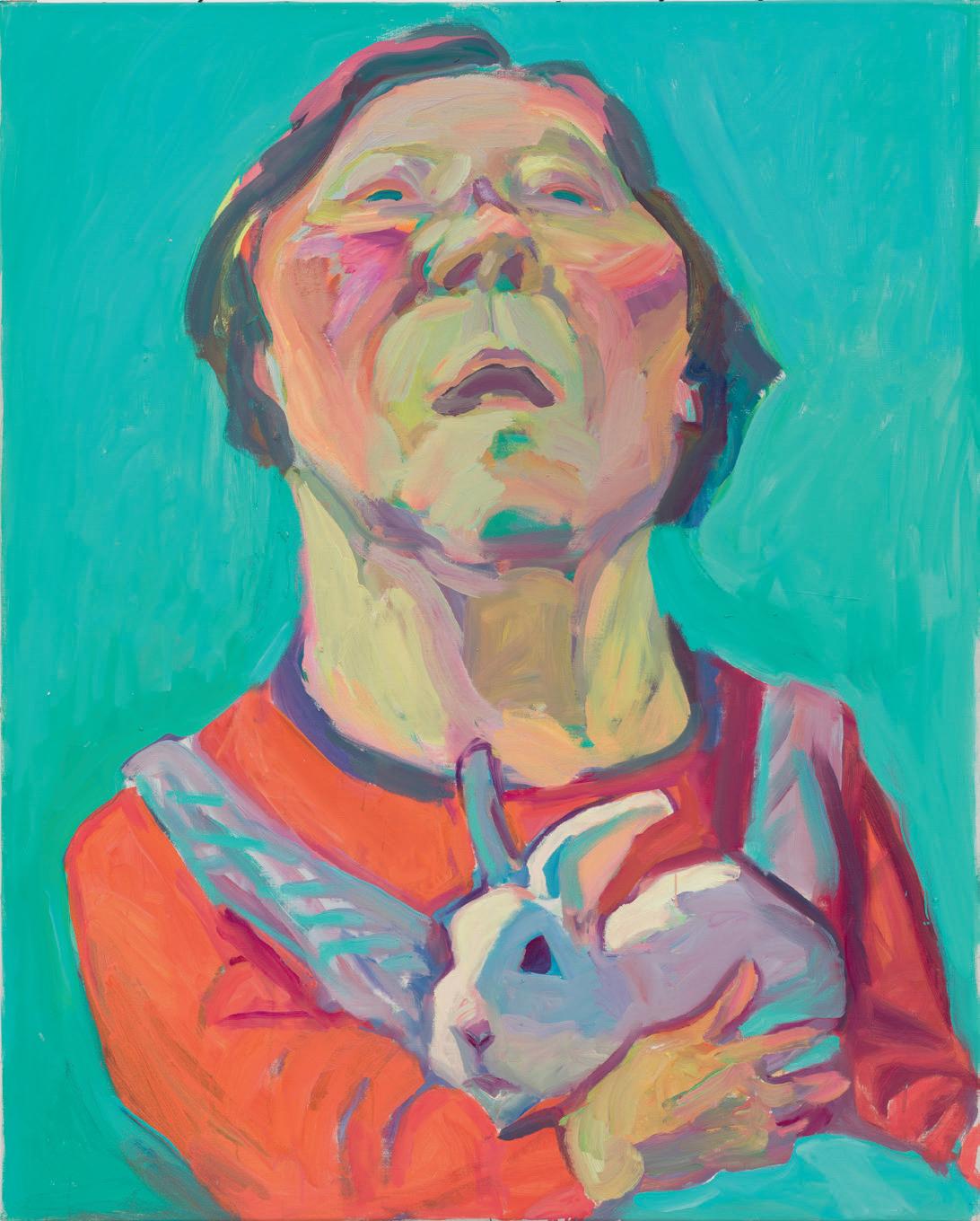

Maria Lassnig by Rachel Haidu

Agnes Martin by Renate Bertlmann

Steve McQueen by Tamar Garb

Francis Picabia by Merlin James

Michelangelo Pistoletto by Barry Schwabsky

Robert Rauschenberg by Susan Davidson

Mira Schendel by Anna Katherine Brodbeck

Michelle Stuart by Anna Lovatt

Santa Catalina Island by Michelle Stuart

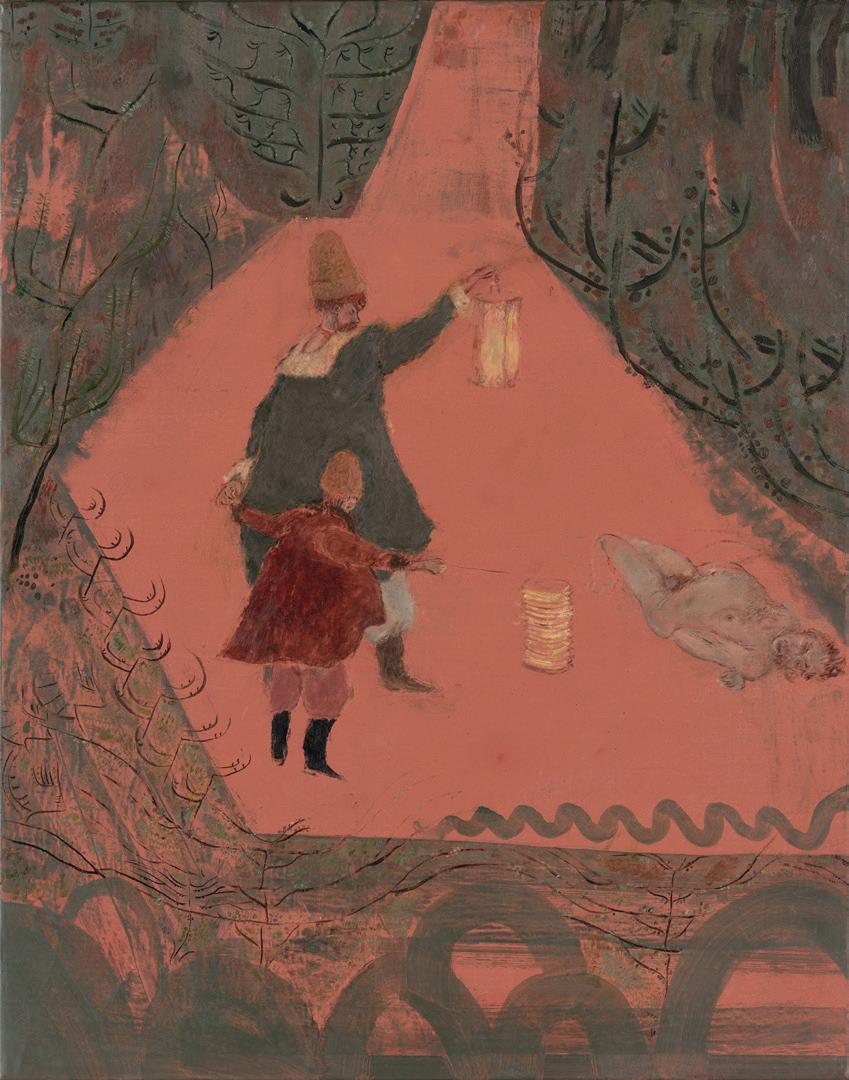

Dorothea Tanning by Susan Aberth

What’s it like living with Anne Truitt by Charles Ray

Cy Twombly by Terry Winters

Hannah Wilke by TR Ericsson

Fred Wilson by Leora Maltz-Leca

Jackie Winsor by Mary Weatherford

Anicka Yi by Kirsten Swenson

Inclusion Implies Exclusion:

A Conversation on Painting in Postwar Germany

Gavin Delahunty in conversation with Isabelle Graw

Endnotes

Contributors

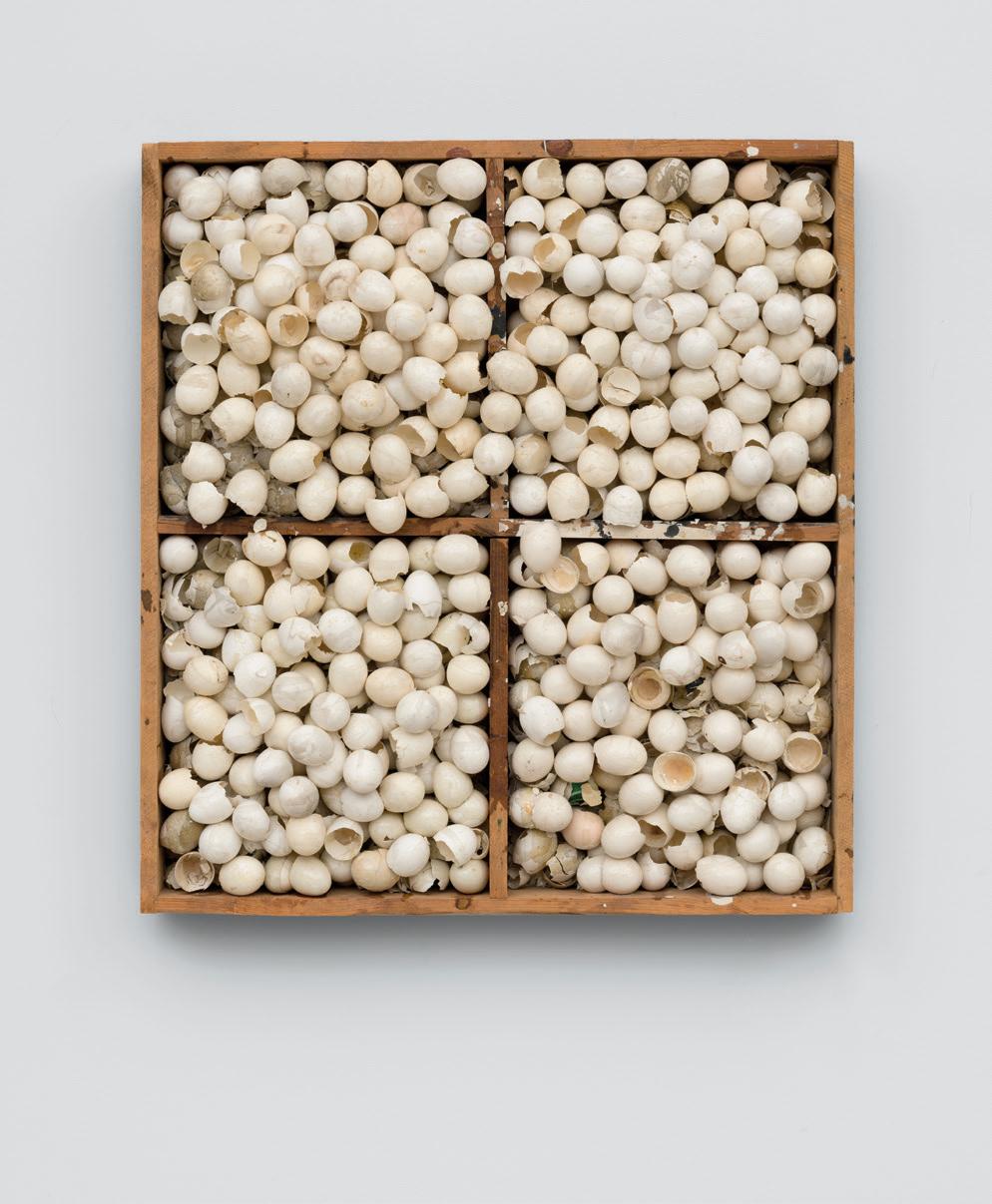

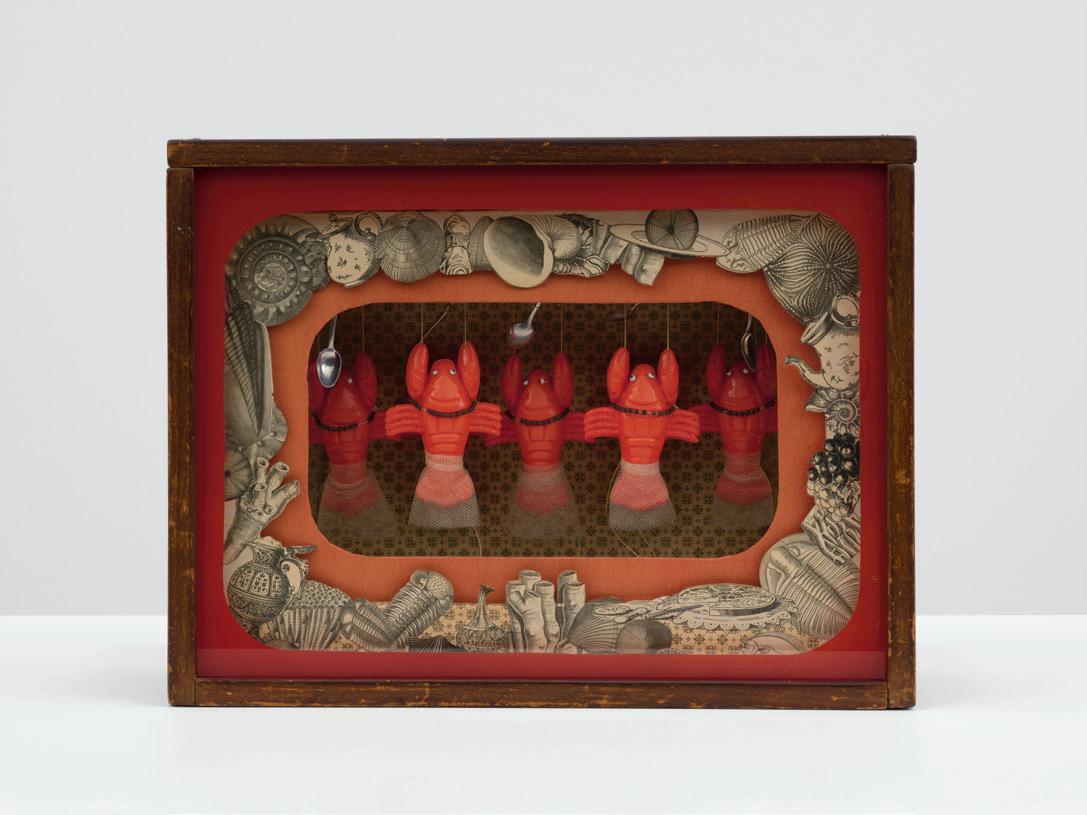

Joseph Cornell A Pantry Ballet (for Jacques Offenbach) , December 1942

Donald Judd Untitled , 1965

Maria Lassnig Untitled (Selbstportrait mit Hasen) (Self-Portrait with Hare) , 2000

STEVE M c QUEEN BY TAMAR GARB

Gold is heavy, but this draped filter feels gossamer-light. Gathered on a circular ring, suspended from up high, it falls in folds and fragile waves to create a golden haze through which light and air can pass. Made to enclose a bodily space, to shroud and shield its supine occupant, the transparent mesh of Weight (2016) is both a protective membrane and a porous screen that reveals and obscures its contents. Through its lace-like weave, a bare bunk is visible, its geometry and basic frame providing the border and edge of the piece. Made to support a man, it is stripped here to its horizontal essence, a minimal, even measly bed that offers little comfort or care.

An accretion of grids, from the rectilinear form of the modest bunk to the fine weave of the metal net, Weight ’s associations are nevertheless heavy and grave. Notwithstanding its transparency and airiness, the work’s primary reference is to the carceral and enclosed. Originating as a site-specific commission, it was, in its earlier double-bunked iteration, made to inhabit a cell in England’s notorious (now defunct) Reading Gaol and formed part of a group exhibition entitled Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison (2016). The exhibition was curated by the London-based arts organization Artangel (which initiates projects for unusual spaces and locations) as a means of marking the fiftieth anniversary of the decriminalization of “homosexuality” in Britain and of commemorating the prison’s most famous inmate, Oscar Wilde, who spent time in virtual solitary confinement under its draconian regime of “separation.” 1 Accused of being a “somdomite” ( sic ) by the father of his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie), Wilde sued for libel and lost. He was convicted of committing “acts of gross indecency with other male persons” and sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labor. 2 It was in Reading Gaol that he wrote the extended “love letter” De Profundis , 3 a meditation on sorrow and solitude and a series of reflections on art, faith and redemptive suffering. McQueen’s bare bunk serves as an empty plinth for the prisoner and his surrogates, the condemned and “other souls of pain” of which Wilde later wrote in his epic poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898),

a paean to the inner life of the prisoner and the outer indifference of the penal system. 4 In this context, the bunk bed reads as a reduced and austere platform made to hold the doomed.

And yet, in Weight , the bunk sits veiled behind a screen of metallic lace that softens its edges and secretes it away, creating a cocoon or enclosure that might seclude its imagined occupant. Like the mosquito net on which it is based, it is dense enough for protection while still allowing light and air to pass through. It fends off danger while enabling sleep. Far from the immovable walls and opaque limits of the prison cell, the golden tent provides a permeable space in which to dream and think beneath the “leaden sky.” 5 Through it one can look out as well as see in, albeit through a heavenly haze. Through it the imagination can soar.

The gold is crucial here. Its connotations are both symbolic and material. Not just tinted or superficially colored, the net of Weight is plated in 24 karat gold, a material freighted with preciousness and precedent. From the flattened grounds of gold-leaf medieval altarpieces to the golden modernist monochromes of Yves Klein and the battered fabrics of David Hammons, not to mention the hanging beads and baubles of Félix González-Torres, the capacity of gold to signify as both matter and metaphor is manifest. Its power lies in its aura as substance, suggesting riches and wealth, status and transcendence, at the same time as it is materially culled from the depths of the earth and must be sourced and transformed by labor and craft. It is both literal and abstract, a substance and a substrate on which the flow of capital is based.

No one knows this more closely than Steve McQueen. For his 2002 film Western Deep he shot, on grainy Super 8 mm film, the suffocating atmosphere of the world’s deepest gold mine, TauTona, situated just outside Johannesburg. Here it is the metal cage descending to the underground “penal colony” that provides the grinding grid, refracted on the faces of the men whose brown bodies and bowed backs unleash the precious stuff from rocks, only to have themselves measured and monitored in lines as they perform their drills semi-naked. Exhaustion, sweat and suffering are written on their faces. They bear the cost of another’s wealth. There is no gold without the grit.

For all its hope and heavenward orientation, its movement towards the light and capacity to allow the supine subject to breathe despite his “separation” and sequestration, Weight is a somber work. It registers the capacity to dream and the need for air, but it cannot help but remind us that the prosaic bunk is shrouded in a wave of gold that someone had to dig, to melt, to make.