WEST AFRICA’S TEXTILE ARTS

DUNCAN CLARKE

DUNCAN CLARKE

These pages are on the artistry of West African textiles, on the artistic achievements of the men and women who wove beautiful cloths, who mastered the ancient skills of indigo dyeing, and who painstakingly stitched the intricate embroidery. The cloths and robes included date mainly from the hundred years between the XVIIth century and 1950 but they represent a window into traditions which extended much further back in time. Even for such a recent period our knowledge remains patchy, a jigsaw with many pieces still missing. It remains one of the abiding attractions of the field that an old cloth can still turn up with a textile dealer in Accra or in the stores of a regional museum in a colonial collection that is completely unlike anything else known to date. Textiles have not received the same degree of scholarly attention as other better known aspects of West African art but there is nevertheless a growing body of literature that sheds light on aspects of this history. We will refer briefly to some of this in the introductions to the country chapters that follow. Here we will touch instead on some of the main themes relevant to the West African region as a whole.

Textile production is an ancient feature of many sub-Saharan African societies. Spindle whorls associated with Saharo-Sahelians and probably indicative of the cultivation and weaving of cotton have been discovered in sites of the Khartoum Neolithic in Sudan dated to the 5th millennium BCE (Ehret 2016:75). In West Africa the earliest actual textile fragments recovered by archaeologists were woolen cloths dated to the 4th–7th century in Kissi, Burkina Faso (Magnavita 2008:245.) Cotton textile fragments from 7th–8th century were recovered at Iwelen and Mammanet in Niger and from the 11th century onwards at Bandiagara in Mali. In the south of Nigeria ninth century textile fragments of unidentified vegetal fibres were found in Igbo Ukwu and traces of 13th century cloths, likely to be cotton and raphia, in Benin. The earliest written reference to textiles in West Africa is also from the 11th century when the geographer al-Bakri noted cloth production and use in the Ghana empire (unrelated to the present country of Ghana, the Ghana Empire existed from circa 300 CE to circa 1100 CE in the area that today forms south eastern Mauretania and part of western Mali). Different types of loom

were associated with different fibres and areas of production. The narrow strip double heddle loom was first used for weaving wool and cotton (with widths from 1 cm to 30 cm) in the Niger bend area of Mali and most probably also in the Kanem-Bornu kingdom (circa 700 CE–1900 CE, centred around lake Chad but extending at times as far north as southern Libya, and controlling areas of present day north eastern Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroun). Historical linguistic analysis suggests that raphia weaving, most likely on a kind of single heddle loom was established among Benue-Kwa people in the rainforest belt, including the “proto-Yoruba” (the distance ancestors of the Yoruba people of today’s south western Nigeria) as early as the 4th millennium BCE (Ehret 2016:62, Ogundiran 2020:35). Indigo dyeing was also of great antiquity. Ancient Egyp-

tian depictions of the men of Punt showed them wearing blue and white striped loincloths while dye analysis of Meroitic textiles between 300 BCE and 300 CE showed frequent use of indigo (Balfour-Paul 1997:119.)

When did people in West Africa begin to weave the elaborately decorated textiles we see in this book? Aside from some of the blue and white patterned cloths found at Bandiagara we simply don’t know but some traditions were clearly producing complex cloths at least by the middle of the second millennium CE. The greater availability of industrially spun cotton in the nineteenth century was an important factor in the development and expansion of new styles of cloth with more complex patterning but many traditions had far earlier roots. Throughout many West Af-

Caravan transporting rolls of white cotton cloth, Mali, 18941896. Photograph by Émile-Louis Abbat. King Atah of Kyebi, Ghana, circa 1900 Basel Mission Archiverican societies, as in other parts of the world, cloth was a primary medium of status differentiation. The desire of the wealthy and powerful to express their high rank through the accumulation and display of luxury textiles was clearly a primary impetus behind the developments in textile design. Textiles were widely traded, both within West Africa and beyond. In the mid nineteenth century the explorer Heinrich Barth called Kano “the Manchester of Africa” reporting that its textiles clothed people throughout entire Sahara. Plain white cloth, transported in huge rolls, was a staple commodity of long distance trade and served as a currency in many regions. Luxury patterned cloths, some with higher value fibres such as silk, were also traded over long distances, with wealthy chiefs and kings assem-

bling and wearing cloths from elsewhere within West Africa alongside textiles from Europe and India. In many areas burial rites were also an important motivation, with a successful funeral for an important person involving the display and burial of hundreds of cloths. Each tradition has its own history, much of which is still to be researched.

In the second millennium CE Islam played a central role in these trade networks, providing the practical necessities for successful long distance trade such as literacy, a credit and legal system and an assurance of hospitality in the communities that grew up along the trade routes. As well as transporting textiles over long distances, bringing wool and cotton textiles from the Niger

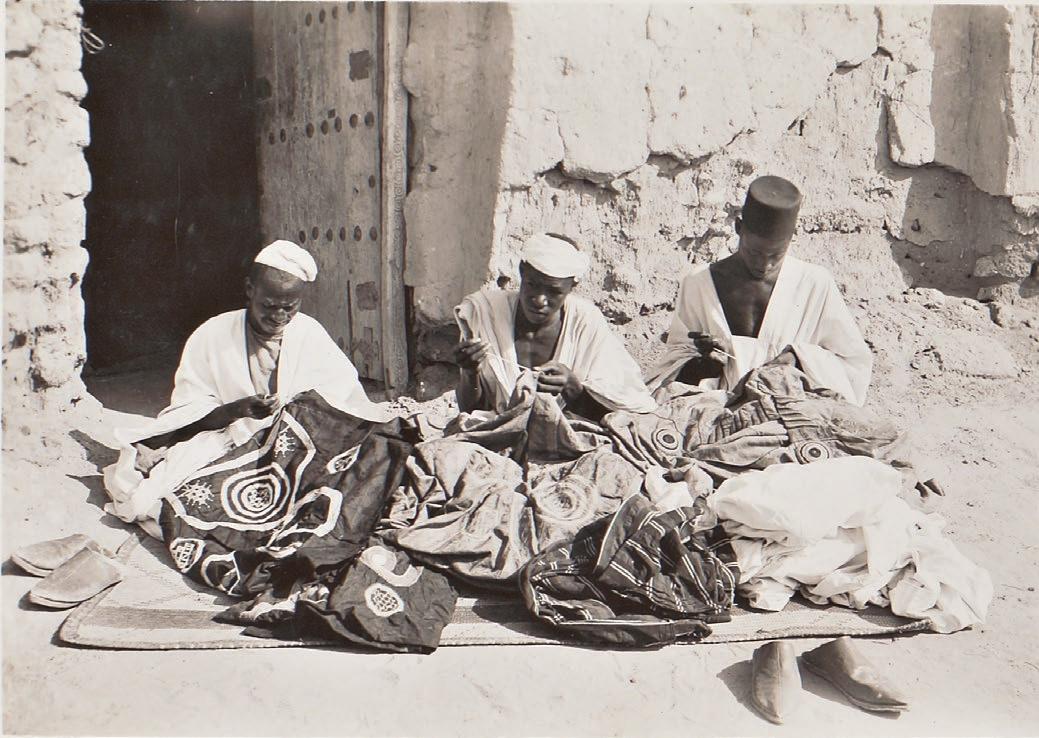

Embroidering men’s robes, Niger, circa 1930

Embroidering men’s robes, Niger, circa 1930

bend to the West African coast by the fifteenth century, Muslim traders were often themselves weavers had an important part and played an important role in the transmission of cotton weaving south from the Sahel into the forest belt. Whilst arguments by writers in the early colonial period that the spread of Islam and an accompanying new sense of modestly by itself accounted for the spread of weaving were oversimplistic, Muslims did contribute to the distribution of weaving technology, to new forms of prestige dress especially embroidered robes, and to a wider conceptual framework that found expression in aspects of textile design.

Mgballa Ekpe (meeting house) with Ekpe members, Arochukwu, southeastern Nigeria, 1989. Photograph by Eli Bentor.

Mgballa Ekpe (meeting house) with Ekpe members, Arochukwu, southeastern Nigeria, 1989. Photograph by Eli Bentor.

Tellem burial caves in Bandiagara escarpment, Mali, 2004 London, Werner Forman Archive

MALI

Intricately patterned woolen cloths up to six metres long formed the walls of the wedding tents of noble Fulani and Tuareg families in the arid Sahel of northern Mali. Woolen blankets protected herders from the ever present mosquitoes and the cold wind of the desert nights. A blue and white cotton cloth wrapped the corpse of a Dogon elder and served as a substitute for the deceased at second burial ceremonials. Embroidered robes encoded esoteric learning and were markers of prestige and Islamic piety. Mali’s position at the southern edge of the Sahara made it, along with Kanem-Bornu in the Lake Chad basin, a key transitional region dominating trade routes between North Africa and the peoples of the forest belt to the south. Kingdoms rose and fell as the wealth of that trade was consolidated and contested. Along with gold, ivory, kola nuts, salt, and enslaved people, textiles were a major commodity in trade within West Africa and beyond. Traders bought Islam south of the desert and important centres of Islamic scholarship developed at Timbuktu and Jenne (present-day Mali) early in the second millennium CE.

The Massina region of Mali (in the inner delta of the Niger river) and adjacent areas of northern Burkina Faso were the only locations where wool was woven in sub-Saharan Africa. Weaving in wool was the preserve of mabuube men, a specialist artisanal group who also served as griots, praise singers and historians, associated over centuries with noble Fulani families. Nobles and mabuube did not intermarry. Two main types of wool cloth were woven, kaasa blankets, and arkilla hangings. These were woven by a special-

ist mabuube weaver employed and hosted with his family for the months of weaving required, to mark the wedding of a daughter in a Fulani noble family (Gardi 2009:64.)

Cotton weaving was once widespread in Mali, with plain white, or blue and white striped handspun cotton cloth serving as a currency and an important trade commodity, transported in huge rolls and ultimately used to make simple pagne and tunics. More elaborate types were associated with weavers from Mande-speaking peoples in the southern part of Mali, in particular Bamana and Soninké living north of Segou.

“Indigenes en tenue de gala”, Sokolo, Mali, 1894–1896.

Photograph by Émile-Louis Abbat.

The elderly man on the right is wrapped in a large blue and white cloth of the munnyuure type, while the second man wears a silk embroidered indigo boubou lomasa

Cotton fragments predominated among the textiles dating as far back as the C11th CE recovered from the Tellem burial caves in the Bandiagara escarpment inhabited today by the Dogon people, providing remarkable evidence of continuity of designs over many centuries. The migration of Mande-speaking peoples into the forest belt to the south, along with demand for both cotton and wool cloths among people more familiar with backcloth and raffia were significant contributors to the expansion of narrow-strip weaving.

The Tellem caves also provided the earliest evidence for the robes and wide trousers that became the predominant form of male prestige dress associated with the spread of Islam across much of West Africa in the second millennium CE. A complete robe from before 1659, with a simple curve of embroidery at the collar, survives in the cabinet of curiosities of Christoph

Weickmann in Ulm Museum (see 1.9). Across the entire region an economy of prestige robes developed in which rulers amassed hundreds of embroidered garments in tributes and tolls then distributed them to lesser chiefs and followers. Numerous distinct regional styles of robe embroidery evolved over the centuries but the links between itinerant Koranic scholars, the more esoteric aspects of Islamic amulet design, and embroidery persisted.

Bogolanfini (or bogolan), so-called “mud cloth” [glossary - cloth decorated with a dye obtained from iron-rich mud and a mordant of plant extracts, traditionally practised by Bamana women] also encoded esoteric knowledge in the surface design of textiles. In this Malian tradition central to Bamana culture, men weave the cotton cloth strips that are sewn together, thus producing the canvas that women decorate through a complex resist process using plant extracts and mud. They provide, according to Professor Sarah Brett-Smith (2014), a means for Bamana women to explore through metaphor and visual form, ideas about excision, fertility, co-wife rivalry and other aspects of their lives that could not be openly expressed in a patriarchal society. The transformation of bogolanfini from an obscure but deeply meaningful local tradition to a globally recognised but radically simplified signifier of African fashion mirrors wider changes in Mali’s ancient textile traditions over the past 50 years. Very little wool weaving remains and the great arkilla cloths of the past are no longer woven (Gardi 2009:66) but the many of the motifs live on in the brightly coloured repertoire of Zarma (also called Djerma) weavers in Niger. Synthetic indigo, with the addition of a few balls of dried indigo, has displaced the painstakingly prepared dye pots of the Soninké and Dogon women specialists, with stencilled resist designs, sometimes including texts, introduced for a new modern clientele. New forms of brightly coloured blankets and hangings became popular in the years after Independence, many woven by the

Above

Traders selling blankets, Mopti, Mali, 1971. Photograph by Marli Shamir.

Washington D.C., Eliot Elisofon Photo Archive

Right

These colourful blankets and hangings, called tapis, began to be woven in Mali around the time of Independence.

descendants of malleebe, non-caste weavers who were dependents of Fulani and Songhay noble families. Multicoloured checkerboard patterned tapi cloths were said to have been inspired by a visit to Mopti in 1960 of the kente cloth wearing Ghanaian President Nkrumah (Gardi 2009:98) and lead in turn to the creation of the remarkable figurative “couverture personnages” in the decades that followed (see 1.24 and 1.25).

MALI

Complete cloth

Fulani or Songhai people, Mali ca. 1900

Hand spun sheep wool warp, natural dyed hand spun sheep wool and white cotton weft, made up of four strips each circa 35 cm width, 256.5 × 139.7 cm Princeton University Art Museum

This rare style of weft-faced plain weave textile is the most obscure of the various types of woollen fabrics once woven in Mali. The absence of complex weft float and tapestry weave [glossary - a section

of the ground weft in a different colour is woven back and forth to make the motif] patterning typical of other Malian wool textiles allows an appreciation of the subtle beauty of the indigo and other plant based natural dyes used. Perhaps surprisingly, given the thickness of the cloth, it was worn as clothing rather than being a hanging. Heinrich Barth, the great German explorer, wrote (1865;III:481) in relation to women’s cloths in Gao: “They were all dressed in one and the same way, but very different from the costume of women in

Timbuktu; for their clothing consisted of a wide shawl made of different coloured strips of thick woollen fabrics, that was fastened under the bosom so that it was almost down to the ankles. Some of them even had this simple, rough garment attached by a pair of short straps attached over the shoulders while for others was simply tied from behind.

Collected in Ghana where woollen cloths from Mali were highly prized and considered to have great spiritual force (Gardi and Gilbert 2021:47.)

MALI

Arkilla kunta (wedding hanging)

Wogo or Songhai people, Niger early twentieth century Hand spun sheep wool and natural dye warp and continuous extra weft float, made up of four strips of 33 cm width, 309.9 × 132.1 cm Princeton University Art Museum

Arkilla kunta (wedding hanging), that would have formed a two sided tent-like structure that hung up within the round house built out of a frame covered with mats. A plainer lower edge strip and a large striped rear section are missing.

An arkilla kunta is similar to the much more commonly found arkilla kerka but has a wool warp, making it much thicker and heavier and a different sequence of patterns. According to Bernhard Gardi ( 2009:90) it’s possible that these cloths, made in a small community whose ancestors migrated from the lake Debo area of Mali to Niger about 200 years ago, represent an earlier archaic form of the kerka style. The kunta tent was commissioned by the bride’s family and on completion was publicly displayed in the family compound for three days before being moved inside the bridal house.

Collected in Ghana where cloths like this were traded for centuries and formed part of the court treasury of powerful chiefs, being used to display regalia, line royal palanquins and similar functions.

MALI

Arkilla kerka (wedding hanging)

Fulani people, Mali

Mid-twentieth century Wool, hand spun cotton, weft faced plain weave, tapestry weave, continuous supplementary weft float, made up of seven strips, 532 × 162 cm Paris, musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac

Beneath a simple weft faced striped strip used for hanging up the long and heavy textile are six rows of richly patterned cloth, woven with coloured wool and white cotton on a white cotton warp. The design is symmetrical around the central wide brown band across the

cloth with rectangular tapestry weave motifs that, according to Bernhard Gardi (2009:86) was called lewruwal, the moon, surrounded by kode, stars. There was a set order and number for the bands of tapestry weave, tunne, and continuous supplementary weft float, cubbe,

patterns that flanked the central stripe. Each pattern had what Gardi called idiomatic and sometimes humorous names, such as “teeth of an old woman” for white then a black gap then white again. Among the Fulani wool weaving was the work of the mabuube, a

specialised artisan group whose wives were potters. An arkilla kerka was required for the wedding of a daughter in Fulani noble family, necessitating the spinning of a large amount of wool and cotton thread (a few months work Gardi noted) and then a suitably skilled

maabo weaver had to be persuaded to undertake the challenging weaving task. He and his family would be accommodated and fed in the bride’s family compound for the 30 to 60 days it took to complete the cloth.

MALI

Kaasa (blanket)

Fulani people, Mali

Early twentieth century Wool, weft faced plain weave, discontinuous supplementary weft float, embroidery, made up of six strips, 203.5 x 130.5cm London, British Museum

Large supplementary weft float patterns in black and brown natural dyed wool form three rows across the white wool ground. At one end of the cloth a narrow rust brown band contains small white

embroidered designs before another row of much smaller weft float motifs.

A plaited cord of wool is sewn along the centre of the cloth dividing it into two sets of three strips, and along the outer edges. Kaasa with this single rust coloured band and simple embroidery are the rarest type and date from the early decades of the twentieth century.

Like all kaasa they were woven by itinerant weavers who belonged to the maabube artisan group. A woman who wanted a kaasa would gather the wool,

spin the thread, and dye it the required colours, before securing the service of a weaver. She would be responsible for feeding and accommodating him in the family compound and giving small daily gifts until the work was completed, paying him, about a quarter of the value of the completed cloth (Gardi 2009:63). The centre of kaasa weaving was the villages around Mopti but they were in high demand throughout Mali and traded widely into Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Nigeria.

MALI

Kosso daamye

Soninke, Bamana or Fulani people, Banamba region, Mali Early twentieth century Hand spun cotton, machine spun cotton, weft faced plain weave, made up of ten strips, 206 x 106.5 cm London, British Museum

Daamye in Bamana means “checkerboard,” from the French damier, chess board. Once quite a common

style of hand spun cotton cloth and still woven in black and white machine spun thread, they were, along with more expensive munnyuure cloths, called “couvertures de Segou” in the colonial era. This is however an exceptionally fine example of the genre, a “marvel” in the words of Malian textile expert Bernhard Gardi (personal communication 2021). He notes the warp dyed in indigo, the depth of colour, the finely sewn original stitching, the white double

weft lines in the border sections, and the addition of the narrow red lines perfectly placed at the centre of the squares. The Banamba region, on the left bank of the Niger, to which he attributes this cloth, was culturally dominated by the Soninke people. red thread was rare in these blue and white textiles and can be regarded as an indicator of luxury status, also present in some of the ancient Bandiagara fragments.

Pagne

MALI

Bamana or Senari speaking people, Mali or Ivory Coast

Before 1910

Hand spun cotton, made up of six strips, 136 × 75.5 cm

Paris, musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac

Clusters of dots, circles, shorter and longer dashes, are painted in black mud-rich dye on the yellow ground. This enigmatic cloth is an oddity among the important group of Bamana bogolanfini cloths assembled before 1910 by Frantz de Zeltner. There was a repertoire of named bogolan designs that Bamana women used to make variations on standard forms, and certainly modifications within the tradition were possible but bogolan designs were typically outlined in negative space by the painted on black dye rather than directly painted as here. Bogolan expert Sarah Brett-Smith suggests (personal communication 2021) that rather than being of Bamana origin this cloth may perhaps be the work of a Senari speaking (“Senufo”) artist. She notes that she sees aspects of both Senari and Fulani wrappers in the pattern layout and that some Bamana say they learned bogolan from the Fulani. Its small size makes it possible that it was intended as a child’s wrapper.

Basiae (young woman’s wrapper cloth)

Fadugu area ?, Bamana people, Mali

Circa 1920s

Hand spun cotton, 97,2 × 170,5 cm Paris, musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac

The five sections that made up a standard bogolan wrapper cloth are delineated with precision, while the motifs are shaded with individual metal spatula strokes of great subtlety rather than the solid black familiar from later twentieth century examples. This alternation of thick and thin strokes has been seen as characteristic of bogolan made in the Fadugu area in the 1920s and 1930s (Brett-Smith 2014:101). Sudanic leatherworking traditions, practised by Moor and Tuareg women as well as Bamana provide a possible source for some of the motifs. Basiae were ritual “red” bogolanfini worn by young women after excision, receiving a second dye bath with twigs and bark from the n’golobe bush while the dyer recited fertility-inducing incantations (2014:65). They absorbed the powerful nyámà of the bloodshed while protecting the wearer against the dangers of jealousy and sorcerers throughout her recovery. Even before the great profusion of “mud cloth” made in nontraditional contexts, by men as well as women, as international and tourist demand multiplied in the final decades of the twentieth century, styles of bogolan changed from one generation to the next. While the artist of this beautiful piece was unrecorded, it marks a particular place and a particular time in the evolution of Bamana textiles.