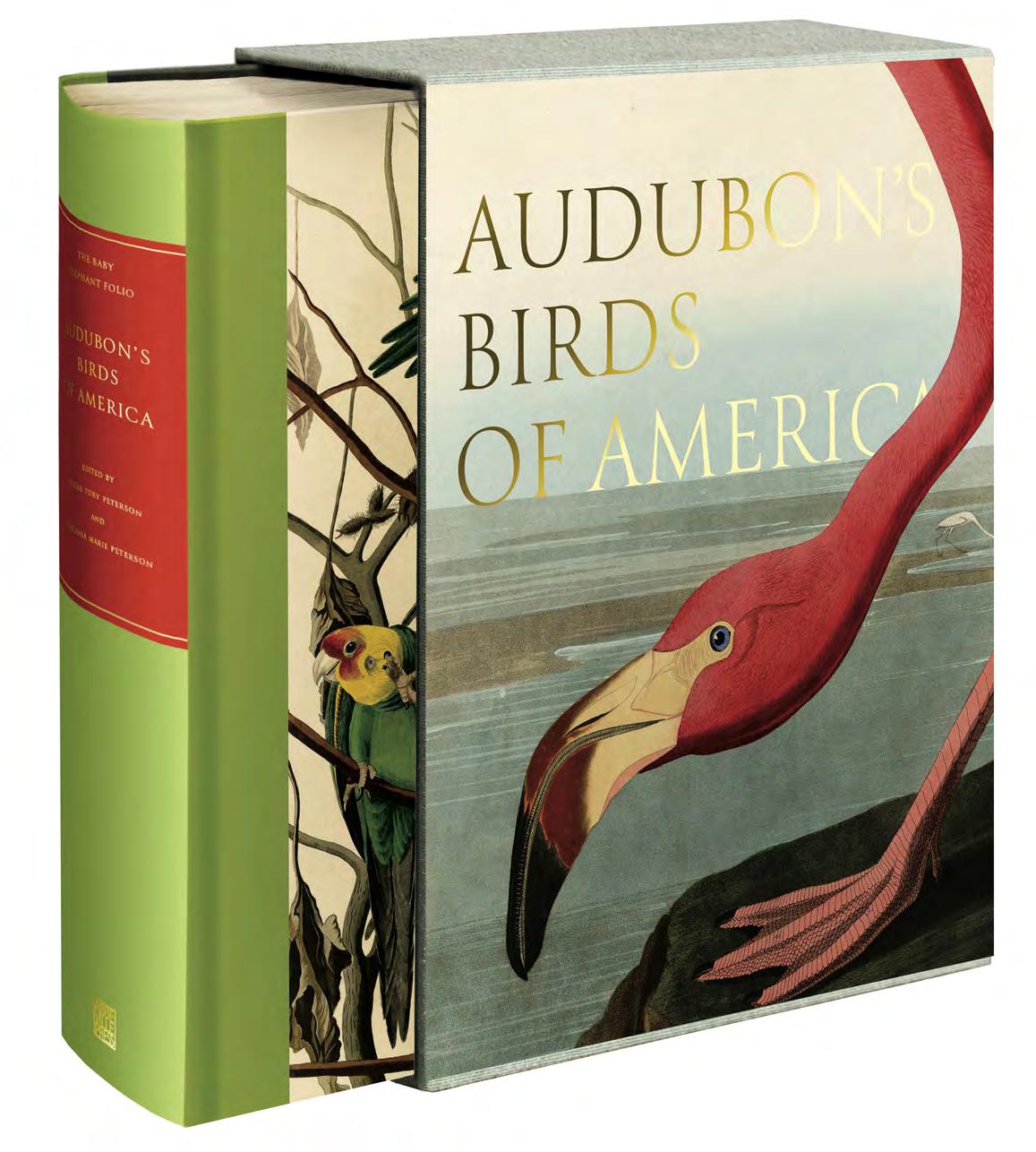

Slipcase: American flamingo [greater flamingo]. See plate 46.

Front cover: Carolina parakeet [Carolina parrot]. See plate 230.

Back cover: Snowy owl. See plate 237.

Title spread: Common merganser [goosander]. See plate 85.

The original edition of the Baby Elephant Folio was designed by Howard Morris and edited by Walton Rawls.

Copyright © 1981, 1990, 2023 Abbeville Press. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017. Printed and bound in China by Artron Art (Group) Co., Ltd.

The Baby Elephant Folio, 2023 Edition

ISBN 978-0-7892-1467-6 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A previous edition of this book was cataloged as follows: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Audubon, John James, 1785–1851. [Birds of America]

Audubon’s birds of America / [edited] by Roger Tory Peterson & Virginia Marie Peterson.—Rev. ed. p. cm.

At head of title: The Audubon Society baby elephant folio.

1. Birds—North America. 2. Artists—United States—Biography.

3. Ornithologists—United States—Biography. I. Peterson, Roger Tory, 1908– . II. Peterson, Virginia Marie, 1925–

III. Title. IV. Title: Birds of America. QL681. A97 1990 598.2973—dc20 90-31607

For bulk and premium sales and for text adoption procedures, write to Customer Service Manager, Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, or call 1-800-A rt B ook

Visit Abbeville Press online at www.abbeville.com.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I Divers of Lakes and Bays, Wanderers of Seas and Coasts (PLA t ES 1–46)

Loons, Grebes, Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, Storm Petrels, Tropicbirds, Pelicans, Boobies, Gannets, Cormorants, Darters, Frigatebirds, Herons, Bitterns, Storks, Ibises, Spoonbills, and Flamingos

II Waterfowl (PLA t ES 47–86) Swans, Geese, and Ducks

III Scavengers and Birds of Prey (PLA t ES 87–117)

Vultures, Kites, Hawks, Eagles, Harriers, Osprey, Caracaras, and Falcons

IV Upland Gamebirds and Marsh-dwellers (PLA t ES 118–143)

Grouse, Ptarmigan, Quails, Turkeys, Cranes, Limpkins, Rails, Gallinules, and Coots

V Shorebirds (PLA t ES 144–185)

Oystercatchers, Stilts, Avocets, Plovers, Sandpipers, and Phalaropes

VI Seabirds (PLA t ES 186–221)

Jaegers, Gulls, Terns, Skimmers, and Auks

VII Showy Birds, Nocturnal Hunters, and Superb Aerialists (PLA t ES 222–252)

Pigeons, Parrots, Cuckoos, Owls, Nightjars, Swifts, and Hummingbirds

VIII Gleaners of Forest and Meadow (PLA t ES 253–297)

Kingfishers, Woodpeckers, Tyrant Flycatchers, Larks, Swallows, Jays, Magpies, Crows, Titmice, and Nuthatches

IX Songsters and Mimics (PLA t ES 298–327)

Dippers, Wrens, Mockingbirds, Thrashers, Thrushes, Gnatcatchers, Kinglets, Pipits, Waxwings, and Shrikes

X Woodland Sprites (PLA t ES 328–381) Vireos and Warblers

XI Flockers and Songbirds (PLA t ES 382–435)

Meadowlarks, Blackbirds, Orioles, Tanagers, and Finches

CONCORDANCE Sequence of this edition related to original plate numbers

INDEX OF BIRD NAMES

blossoms and leaves. Audubon wrote to Lucy, “He now draws flowers better than any man probably in America.”

Joseph Mason, who as a remarkable boy of thirteen had been one of Audubon’s pupils in Cincinnati when he was giving art lessons to raise funds, showed such promise as a botanical artist that Audubon took him on his 1820 trip down the Mississippi. Mason was his assistant for about two years, and most of the leaves and flowers in those plates painted in Louisiana during 1821 and 1822 are his work. He was incredibly skillful for a youngster of that age. At least 57 backgrounds are credited to this young genius. He seems to have disappeared into limbo after leaving Audubon’s employ, but he is immortalized in Audubon’s bird prints.

During the next several years Audubon may have painted his own backgrounds, but in 1829 he met George Lehman, who was to assist him for the next four years, accompanying him on his trips to the shore and to Florida. Although Lehman was an experienced landscape painter, his leaves and other accessories are a bit more labored and cluttered than those of Mason, who had an innate sense of abstraction and pattern. Lehman’s landscapes give a different look to many of the paintings that were made during that productive period; they were more environmental, but less decorative. Lehman is known to have painted the backgrounds for about forty plates, but he probably did more. He even painted an occasional bird; the lesser yellowlegs in plate 163 is credited to him.

Time was important once the great work was fully under way. Flowers and leaves took as long to paint as the birds, so Audubon was pleased to enlist a third helper, whom he met in Charleston, a maiden lady by the name of Maria Martin, who later became Reverend John Bachman’s second wife. She had a well-tended garden, painted flowers and butterflies quite well, and is credited with drawing the flowers and leaves in about twenty of the paintings. They are not the equal of Joseph Mason’s work; her twigs and stems lack his structural strength. The butterflies and moths that appear in six of the plates are presumably hers.

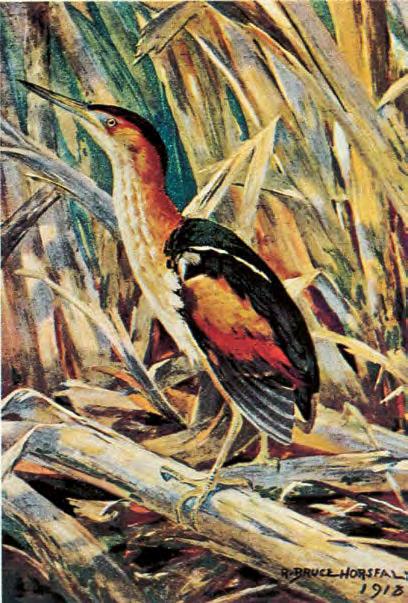

Audubon’s two sons were also drawn into the project. His younger son, John Woodhouse Audubon, who became an accomplished artist, helped with some of the work while in London and actually drew a few of the birds, notably the American bitterns in plate 40. The elder son, Victor Gifford Audubon, painted some of the backgrounds in the later western subjects, but they are more stilted than those of Lehman. It is believed that even Lucy Audubon may have painted at least one bird, the swamp sparrow (plate 426). Add to these efforts the skill and expedient innovation of Robert Havell, Jr., the engraver, who improvised branches and twigs where needed, or even full backgrounds where none existed, and we have, in effect, paintings by committee.

Twelve years after Audubon’s death in 1851, his widow Lucy sold the original paintings to the New-

York Historical Society, where they can be seen today. Reproductions of Audubon’s work invariably were made from the Havell prints until 1966, when the American Heritage Publishing Company of New York and the Houghton Mifflin Company of Boston went directly to the original watercolors. It is instructive to compare the originals with the prints, because Havell was in a sense no less a genius than Audubon and left his own artistic stamp on the plates, sometimes even improving them. Some are literally scissors-and-paste jobs. A pastel made in 1820 might be copied in watercolor ten or twelve years later or simply cut out and pasted onto another drawing. Audubon did not hesitate to mix mediums. Pencil, ink, pastel, watercolor, and even oil were combined in some compositions.

America was reawakened to the splendor of Audubon’s work in 1937, when the Macmillan Company of New York reproduced, in smaller size, 435 prints from the Elephant Folio and an additional 65 prints from the octavo edition. Although the reproductions left much to be desired, they were a breakthrough. Audubon’s prints have been reproduced a number of times since in various forms, and they reached their greatest audience when they graced the calendars of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee. Over a period of twenty years more than ten million well-reproduced and framable Audubon prints were distributed in these calendars.

Audu B o N ’ S r EP ut A t I o N S kyrock E t E d upon publication of his great work. Baron Cuvier, the French naturalist, rated it the “most magnificent monument which has ever been raised to ornithology.” But every genius has his or her critics. One subscriber discontinued her subscription after she received the first lot of prints, numbers 1 to 9. She pronounced them so very bad that she could not think of giving “house room” to any more such “trash.”

Not counting his own living costs and those of his family, Audubon spent $115,640 to complete his project. Approximately 200 sets of the Double Elephant Folio were bound and distributed. They were priced at $1,000 each. It was thought that more than half these sets had been broken up by 1970 and sold by dealers as individual prints. However, through the extraordinary investigation of Waldeman H. Fries, we find this was far from true. When he documented the sets in his scholarly work The Double Elephant Folio: The Story of Audubon’s Birds of America (Chicago: American Library Association, 1973), about 134 complete sets survived. Of these, 94 were in the United States, 17 in England, and the remainder in twelve other countries. It attests to the fortitude of Fries (and his wife) that he was able to examine all but six of these sets. In addition, 14 incomplete sets survived, 28 sets were broken up, 11 were destroyed by fire or war, and 14 had disappeared. It was rumored that one unanticipated spinoff of the Fries book was that thieves, finding the locations of existing sets pinpointed, made off with three of them. All three were eventually recovered.

Nearly a century elapsed before the original investment of $1,000 per set really began to pay off in the collector’s market, in direct proportion to the vastly increased interest in birds that had begun to accelerate with the publication of modern field guides. In the 1920s, a collector or speculator could have acquired a set of Audubon at auction for about $2,500. By the mid or late thirties it would have been closer to $12,000 or $14,000; by the mid-forties, $18,000; in 1960, $60,000 was paid for a set; and in 1969, $216,000. In 1977 a set was sold at auction for $400,000, and the price continued to climb. On June 23, 1989, at an auction at Sotheby’s, the total realized from a set that had been broken up was $3,960,000!

Individual prints that could have been purchased at Goodspeeds in Boston for $7.50 to $25.00 in 1905 went for $500 to $4,000 or more in the late 1970s. The wild turkey—“The Great American Cock”—rose from $200 in 1905 to $20,000 in 1980 for one in mint condition. At an auction at Sotheby’s in 1989 a print of the mallard that fetched $45,100 was bettered by four prints: the trumpeter swan ($49,500), the white pelican ($58,300), the great blue heron ($66,000), and the

The Double Elephant Folio

His later work has gone more toward canvases where the birds are subordinate to the landscape or are used as accents to the environment. He explained, “For me, art is self-realization. By combining descriptions and feelings of what I see and externalizing them, I comprehend reality—my own life. It is for others to make of that what they will.” Eckelberry is one of the very few bird artists to be elected a fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

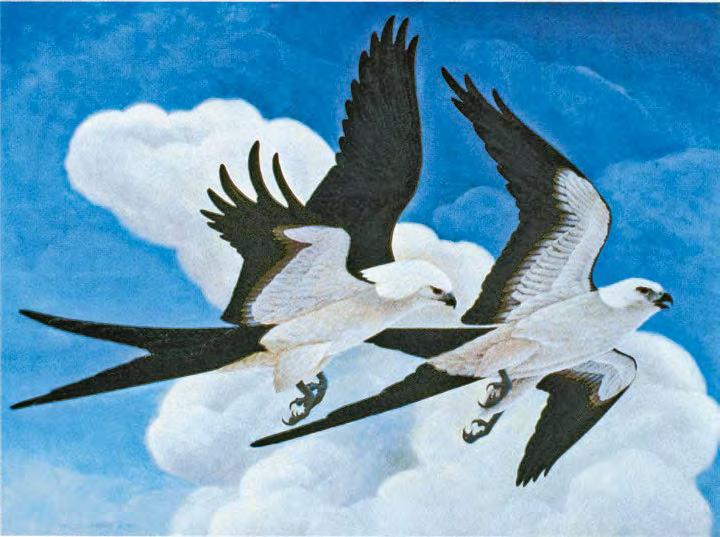

Guy Coheleach (pronounced Ko-le-ak) did not climb the ladder of success at the same speed as most other artists—he ran up. Trained at the Cooper Union Art School, he came to wildlife art not by the academic or museum route but by way of the jungle of Madison Avenue’s advertising-art world. He had always been deeply interested in wildlife, especially birds, and Eckelberry talked him into making the switch to bird and wildlife painting. Bringing his commercial expertise to bear on bird art, Coheleach met with immediate success.

He is concerned about the future of wildlife and the environment and has donated many original paintings and the profits of many prints to save endangered species and to work for a better natural environment. Because of his earlier training he is one of the most professional wildlife artists and is not locked into any single approach or technique. If asked to do so, he can paint a near-Fuertes, a creditable Jaques, or a simulated Liljefors. Although able to paint in any style, he has finally settled down to the real Coheleach. Meanwhile he has helped other competent wildlife artists to make a good living by raising the level of prices they can ask for their work.

His gift for painting character, motion, and life into his birds is as deep as his thirst for adventure. A world traveler, Coheleach has climbed mountains; caught rattlesnakes and pythons; tracked eagles, lions, and rhinos; and been chased by elephants (even knocked down by one). He lives every day for what it is worth (in this way reminiscent of Audubon). Although he may draw dozens of study sketches before he touches brush to canvas, he paints rapidly—“The fastest brush in the East,” quips Eckelberry. “Not so,” Coheleach adamantly retorts. “I sweat blood.”

Manhattan may seem an unlikely birthplace for one of America’s finest and most prolific bird portraitists, but the late Arthur Singer found advantages there. The American Museum of Natural History was nearby on the west side of Central Park, and the Bronx Zoo was only a subway ride away. He became imprinted by the zoo at the age of three and by the time Singer was in high school, he was already selling his sketches. He trained at Cooper Union Art School, where he later taught layout and

design. Singer was one of the few professionals who always met his deadlines. This dependability made him very popular with publishers. He gained a large following both in the United States and abroad through his illustrations in his bird guides as well as his limited-edition prints. Amongst other honors he received the Master Wildlife Artists’ Medal of the Leigh Yawkee Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin.

Singer’s approach was basically that of a skilled delineator in the Audubon and Fuertes tradition. He had no fear of typecasting, which kept him busy with commercial illustration, but more and more he painted for the galleries and to please himself. He scheduled at least one vacation trip a year into some area he had not seen or birded before. Like Audubon’s sons, Paul and Alan Singer are following in their father’s footsteps as wildlife artists.

Robert Verity Clem was one of the first contemporary bird artists to try a new direction. When he was very young his bird portraits were much like those of Fuertes. On one of his visits to the Peabody Museum at Yale, the late Rudolph Freund said to him, “You can draw a bird on a stick, but can you put it into a landscape?” This was a challenge, and Clem soon proved that he could. Most people know his work through the 32 magnificent colorplates in Shorebirds of North America (New York: Viking Press, 1967), but he now refuses to paint for reproduction, contending that even the best limitededition prints cannot match the subtleties of an original. A true artist and a perfectionist, he paints as he pleases, and his clients do not dictate the subject matter. Shorebirds are his favorites. His birds, which once dominated the landscape, are now subordinate to it. He emphasizes the environment and its moods. Clem lives and paints on Cape Cod, where he has the sea and the shore at his doorstep.

Albert Earl Gilbert is an artist of whom Fuertes would have approved; his style when painting bird portraits in watercolor is sure and direct. He does not overwork his detail, yet everything essential is there. His concepts are nonderivative and always original. He seems to produce his orchestrations unself-consciously; his paintings read easily.

Gilbert wanted to be an artist ever since his boyhood in Chicago, where he spent much of his time at the Brookfield Zoo. By the age of twelve he was sketching at the zoo under the tutelage of curatorartist Karl Plath. Later he received advice and criticism from George Sutton.

Gilbert has to his credit many fine paintings in standard ornithological monographs, notably the sumptuous Currassows and Related Birds, by Amadon and Delacour, and Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World, by Amadon and Brown. His paintings may be found in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Field Museum of Chicago, and many private collections.

For years Gilbert’s art has received wide exposure in the stamp program of the National Wildlife Federation, and in 1979 he won the Federal Duck Stamp competition. Using his windfall from the

13. Audubon’s Shearwater [Dusky Petrel] Puffinus

lherminieri [Puffinus Obscurus]

In the great seagoing family of tube-nosed seabirds, the shearwaters and petrels, there is a small species, Audubon’s shearwater, that wanders northward off our coast as far as Cape Hatteras and rarely to Cape Cod. The birder is not likely to see this bird of subtropical and tropical seas unless he takes a small fishing boat far offshore into the Gulf Stream; it is seldom seen from the beaches, unless storm-driven. Black above and white below, and half the bulk of the larger shearwaters, it can be confused only with the Manx shearwater (previous plate), a more northern, Old World species Its natal home is

on islands in warmer seas—Bermuda, the West Indies, Cape Verde Islands, and the Galapagos. It seldom has been sighted in the Gulf of Mexico in recent years, but Audubon reported great numbers when his ship Delos was becalmed in the Gulf of Mexico near the west coast of Florida when he was sailing from New Orleans to England in 1826. The mate killed four at one shot, and Audubon made a pencil sketch of one that was translated into watercolor several years later. Havell put in a rocky shoreline, which, of course, was inappropriate for Florida.

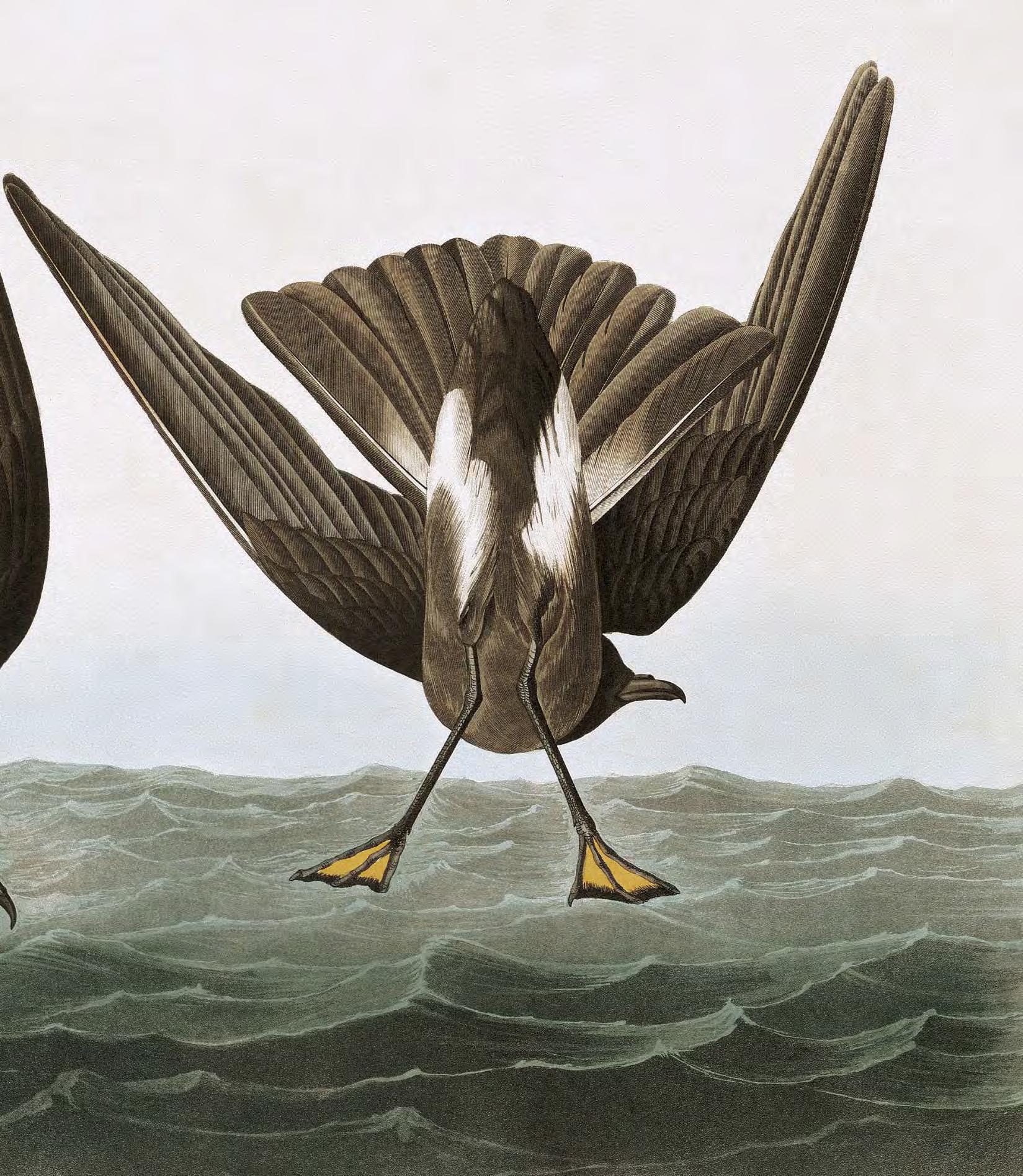

14. Leach’s Storm-Petrel

[Forked-tailed Petrel] Oceanodroma leucorhoa [Thalassidroma Leachii]

Storm petrels are the “Mother Carey’s chickens” of the ancient seamen, little dark birds with white rumps, scarcely larger than swallows, that dance on the water as Audubon has portrayed in his colorplate. Only one species nests on the Atlantic side of North America—Leach’s storm petrel, which Audubon found abundant off the banks of Newfoundland and collected in spite of the giddiness and nausea that never left him when at sea. He obviously knew this species well, stating that it bred on all suitable places from the islands off Mount Desert in Maine to Newfoundland. He noted that its flight differed from that of Wilson’s storm petrel, with

broader wheelings and more erratic flappings suggesting a nighthawk, and that it usually did not come close around the vessel as Wilson’s petrel often did. Leach’s petrel is found on both sides of the North Atlantic as well as in the North Pacific. Its nesting colonies are underground, in the turf of offshore islands. Although Leach’s is the breeding-petrel of the North Atlantic, it is less often seen at sea than Wilson’s petrel, which comes to us from the Antarctic; presumably because it feeds much farther offshore. It can be distinguished not only by its more erratic, less fluttering flight, but also by its notched or forked tail.

15. Wilson’s Storm-Petrel [Wilson’s Petrel] Oceanites oceanicus

Wilson’s petrel was named after Alexander Wilson, Audubon’s contemporar y. Although breeding in the Antarctic, this dainty seabird ranges into the North Atlantic during the summer, which is then winter in the Southern Hemisphere. Audubon did not know that they nested at the other end of the world, nor did anyone else; he presumed that they bred on some of the small islands, called the “Mud Islands,” situated off the southern extremity of Nova Scotia. He wrote, with seeming authority, “Thither the birds resort in great numbers about the beginning of June and form burrows to a depth of two or two and a half feet in the bottom of which is laid a single white egg.” All of this sounds very positive; actually the birds

must have been Leach’s petrels. Audubon’s information (or misinformation) must have come from local fishermen. Wilson was no better informed and stated that this petrel bred in the Bahamas. Actually its breeding grounds are thousands of miles to the south on islands and headlands around the Antarctic Continent, where it treads the water amongst the floating ice, coming in at dusk to fissures in the volcanic rock where it lays its single egg. Audubon, who suffered from seasickness, wrote, “A long voyage would always be to me a continued source of suffering were I restrained from gazing on the vast expanse of the waters and on the ever pleasing inhabitants of the air that now and then appear in the ship’s wake.”

16. European Storm-Petrel [Least Petrel]

Hydrobates pelagicus

In August, 1830, becalmed on the banks of Newfoundland, Audubon, according to his account, “obtained several individuals of this species from a flock composed chiefly of Leach’s Petrels, and Wilson’s Petrels.” He thought they were a new species but closer inspection showed them to be the well-known European bird. He was assured that it bred in the sandy beaches of Sable Island off the coast of Nova Scotia. He concludes his account with the contradictory statement, “not observed to breed on the American coast.” Audubon’s record was later discredited because his specimens were no longer in existence, and the species was removed from the North American list. Recently it was reinstated after a specimen was taken

at Sable Island, of all places. Could it be that the bird really does breed there occasionally? This seems unlikely as the island is thoroughly worked by field ornithologists these days, but it is quite possible that transatlantic wanderers could reach this isolated sea island from time to time, unobserved because of their close resemblance to the numerous Wilson’s storm petrels. The European storm petrel is smaller than Wilson’s, has shorter legs, and the feet, which lack the yellow webs, do not extend beyond the square tail. The whitish patch on the underwing, a good field mark, is well-shown in Audubon’s drawing. His general account of its habits in his Ornithological Biography is quoted from a British naturalist, Mr. Hewitt.

17. White-tailed Tropicbird [Tropic Bird] Phaethon lepturus

The specimens from which Audubon drew the figures in his colorplate were taken in the Dry Tortugas off Key West in the summer of 1832 by Robert Day, Esq., of the United States Revenue Cutter Marion. These two birds were shot out of a flock of eight or ten. Inasmuch as Audubon had never had the opportunity of seeing this species in life he was unable to give much information about it. To this day, the one spot in the United States where tropicbirds are consistently seen is in the Dry Tortugas, but a flock of eight or ten would be most unusual. Usually not more than one or two are ticked off by birders during the course of a visit to those semitropical is-

lets in the Gulf of Mexico. Tropicbirds breed commonly in Bermuda and on many islands scattered through the warmer parts of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Although waifs have been reported after hurricanes as far north in the Atlantic as Nova Scotia, the best chance one has to see this bird in the continental waters of the United States is off the Florida Keys. Tropicbirds fly pigeonlike, on strong, quick wing-strokes over the sea and plunge for food rather like terns. At Christmas Island, south of Java, there is a golden form of this bird that is especially beautiful.

18. American White Pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos [Pelicanus Americanus]

With justified elation, Audubon wrote, “I feel great pleasure, good reader, in assuring you that our White Pelican, which has hitherto been considered the same as that found in Europe, is quite different. In consequence of this discovery I have honored it with the name of my beloved country, over the mighty streams of which, may this splendid bird wander free and unmolested.” It was well known to him that this majestic bird nested far to the northwest in the “fur countries,” but he was puzzled as to why at that same season he saw some along the Gulf of Mexico. His friend the Reverend Bachman of Charleston stated that it formerly bred on the sandbanks of South Carolina. He saw a flock on the bird banks off Bull’s Island on the first of July, 1814, and was under the impression

that they had eggs on one of those banks. Audubon, thinking about this, wrote, “Reader, I have thought a thousand times perhaps that a portion of the myriads of ducks, geese and other kinds which leave for higher latitudes were formerly in the habit of remaining and breeding in every section of the country that was found to be favorable. It seems to me that it is now on account of the constantly increasing numbers of our hostile species that these creatures are urged to proceed towards wild and uninhabited parts of the world where they find that security from molestation necessary to enable them to rear their innocent progency.” Although in his early years Audubon was “in blood up to his elbows,” he obviously became more reflective and compassionate later on.

19. Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis [Pelicanus Fuscus]

The seriocomic pelicans with their accordion-pleated pouches are the delight of every tourist who visits the beaches of Florida or California. The most popular pelicans of all are perhaps those that make the piers around Tampa and St. Petersburg their headquarters, patiently sitting on their posts until someone offers a handout. At once profoundly dignified, as birds of such ancient lineage should be, they are at the same time masters of deadpan clowning, particularly when two or three birds contend for the same fish. These pelicans that prefer begging to an honest living probably nest with the hundreds of their kind that resort to the mangrove islands well out in Tampa Bay. Many are accidentally hooked or tangled in

the lines of fishermen and become sorely injured. They are rounded up by the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary in St. Petersburg where hundreds of pelicans are rehabilitated yearly. Pelicans fly in orderly lines, close to the water, flapping, then sailing, each bird taking its cue from the bird in front of it, as if they were playing follow-my-leader. Fishing, the big birds fly aloft, spot the schools of small fry, and, facing downwind, pull their wings back and plunge beak-first with a grand splash. The brown pelican, which is the state bird of Louisiana, has a wingspread of six and a half feet. It is strictly coastal, whereas the white pelican, with a wingspread of nine feet, nests far inland in the western half of the continent.

20. Brown Pelican [immature] Pelecanus occidentalis [Pelicanus Fuscus]

How different was the attitude toward pelicans when Audubon wrote, “I procured specimens at different places but nowhere so many as at Key West. There you would see them flying within pistol shot of the wharfs, the boys frequently trying to knock them down with stones.” Today, when a pelican appears on a Florida dock, people throw fish, not stones.” Audubon noted that “its numbers have been considerably reduced, so much indeed that in the inner bay of Charleston, where twenty or thirty years ago it was quite abundant, very few individuals are now seen.” He found the pelicans “year after year retreating from the vicinity of man.” He feared they would be “hunted beyond the range of civilization.”

There is no doubt that the brown pelican recovered some of

its numbers since the early years of this century when Theodore Roosevelt created the first federal refuges and set aside an island on the east coast of Florida for pelicans. In the late fifties and early sixties calamity from another source struck. Toxic poisons in the food chain, presumably from contaminants pouring into the Gulf of Mexico, completely wiped out the pelicans in Louisiana and Texas. In 1968 they were reintroduced into Louisiana with birds from colonies that still persisted in Florida. They are now again widespread in the Gulf. This young pelican, painted in New Orleans, was one of Audubon’s mixed medium efforts: a combination of pencil, watercolor, pastel and oil.