chapter 2 embrOIDereD SIlk

hOrSe cOver

Mariachiara Gasparini

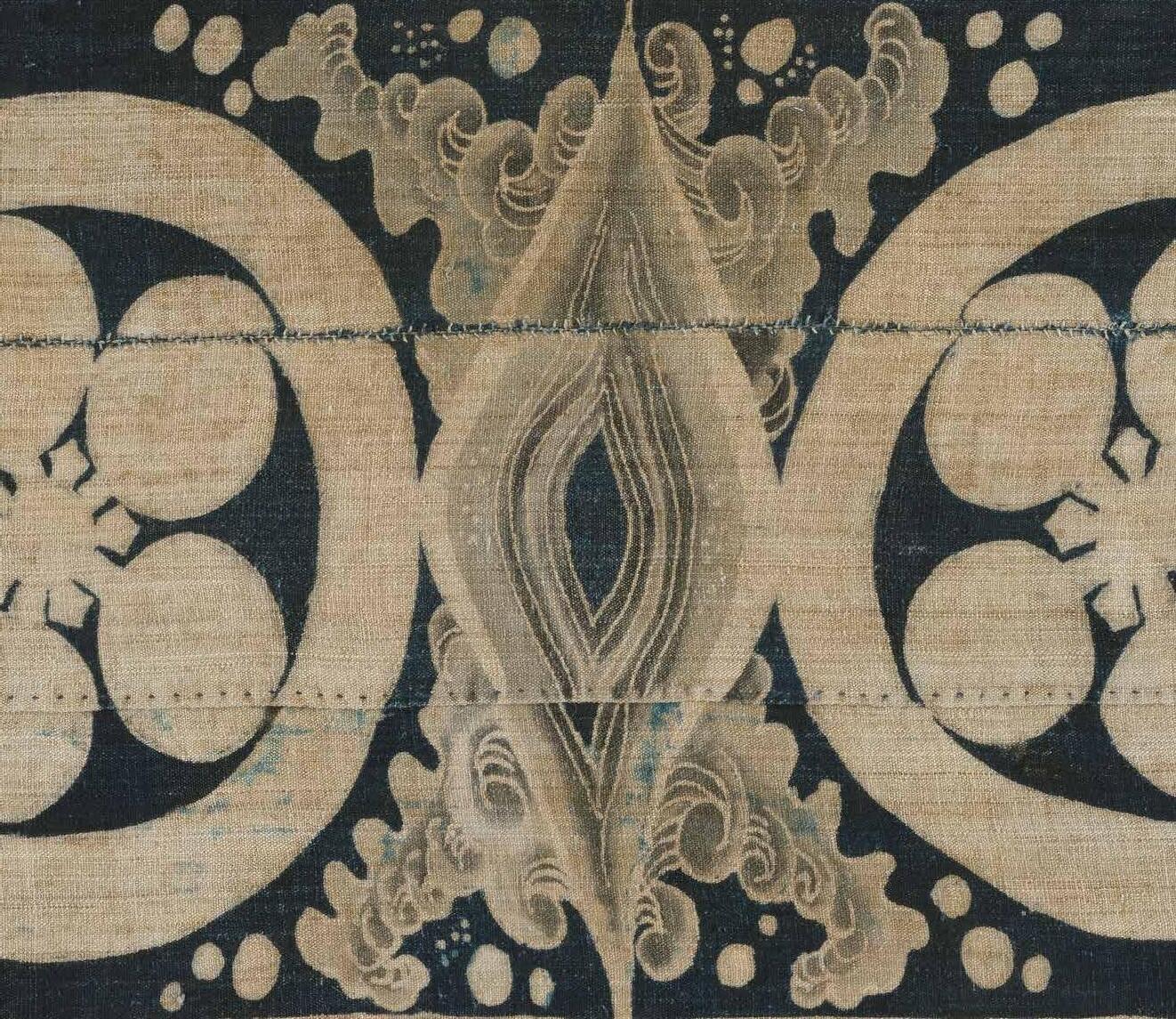

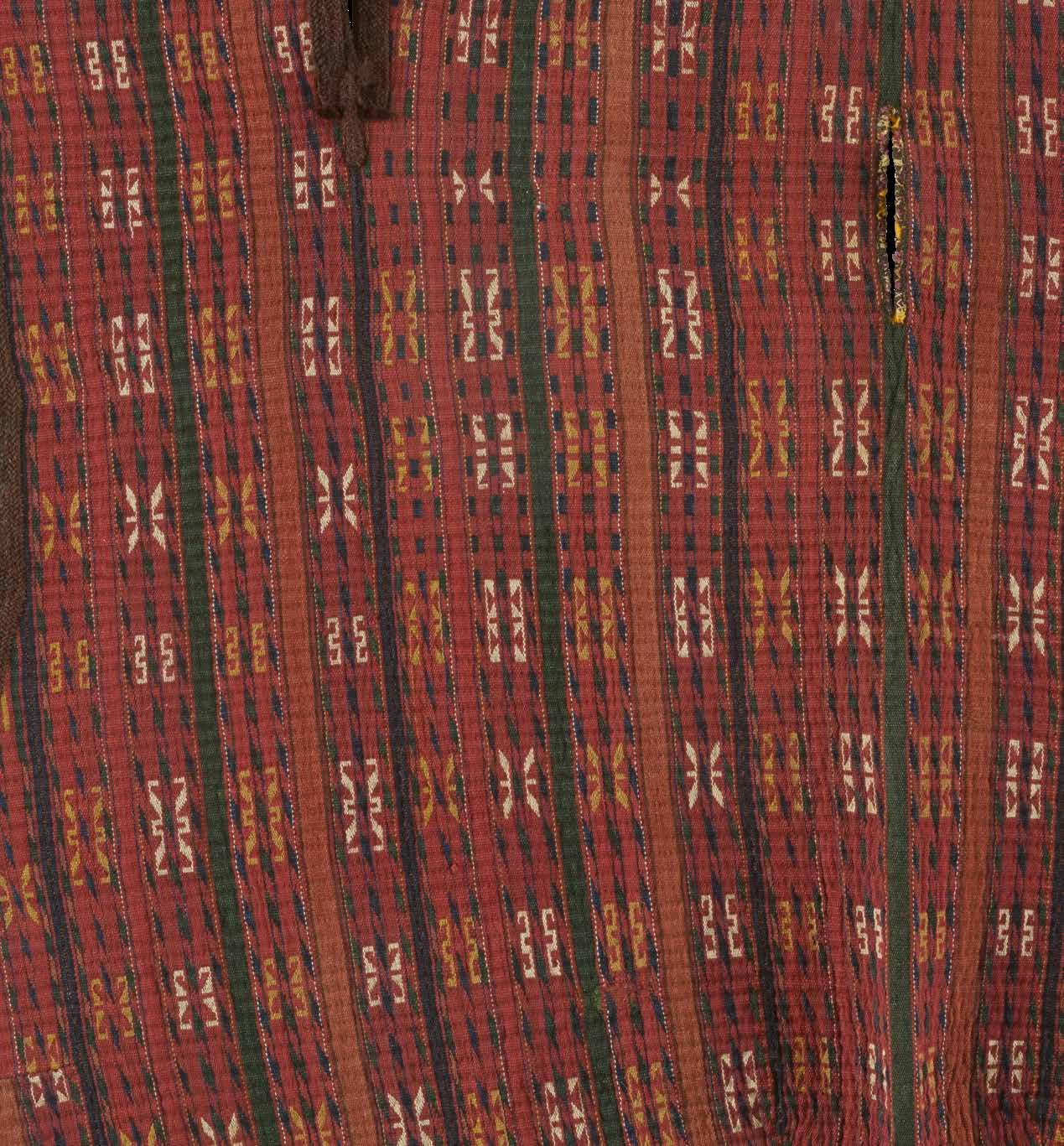

The embroidered silk horse cover in The Textile Museum’s Brick Freedman Collection is a representative, idiosyncratic example of a style that developed between present-day western China and Central Asia around the fifth century and continued to evolve until late antiquity. There is no information regarding the context of its discovery, but, like many similar objects, it reached Nepal, where it was acquired and sold on the art market. Despite the lack of information on its acquisition, other similar items in private and public collections, along with extant Central Asian and Chinese visual sources, provide some historical and artistic context that helps us to date the horse cover to between the fifth and seventh centuries, during a period of great turmoil and crosscultural interactions. Although the background silk is most probably Chinese, the embroidered composition includes foreign motifs that have often been categorized as Sasanian or Sogdian because they are primarily associated with the costumes portrayed in Taq e Bostan’s rock reliefs in Iran or the mural paintings of Afrasiab (Samarkand), Uzbekistan.1 However, similar textile representations are also seen in Tokharistan (former Bactria; present northern Afghanistan and Uzbekistan) and Buddhist Caves in Xinjiang, and the Gansu Provinces of China. In Central Asian paintings, besides costumes, rectangular horse covers featuring beaded roundels can be spotted under the saddles of elephants and horses. Also, the same types of covers appear in the so-called “Sino-Sogdian” tombs discovered in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia Province, which depict the complex multicultural milieu of the time.

In the fourth century, the Tuoba people from the Xianbei confederation of the northern steppes moved to the northern regions of today’s China and established the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535 CE). The Northern Wei was the first of five Northern Dynasties (and five Southern Dynasties) that ruled over China until the sixth century, and which were eventually succeeded by the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE). Their non-Han nomadic background made them more receptive to foreign ideas and customs across and beyond the borders.2 Concurrently, the Tuyuhun, also descended from the Xianbei, relocated to Qinghai and in 663 were eventually conquered by the Tibetans, who recorded them using the name Azha.3 The information on the Tuyuhun is scant, but the extant sources suggest that they were among the people who mediated trade and exchanges along the Qaidan Basin in the northeastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet plateau with the Northern Wei and Central Asian people, including the Hephthalites from Tokharistan who expanded their domains beyond the Hindukush to the Tarim Basin. The Hephthalites, who might have migrated from the Altai, and the Tuyuhun most probably spoke a similar para-Mongolic language.4 Nonetheless, archaeological evidence from Qinghai and Gansu has also confirmed the use of Chinese script among the Tuyuhun, who might also have mediated the trade between China and Central Asia.5 According to Chinese accounts, between the fifth and sixth centuries the Hephthalites and the Tuyuhun sent various envoys to the Chinese court. The Hephthalites sent the first envoy to the Northern Wei in 456, and between 507 and 531 they dispatched thirteen other embassies.6 The Tuyuhun sent fifty-six envoys between 473 and 534 and traded large quantities of animals, such as horses, camels, yaks, and Persian mares, for silk.7

At the time, the four primary Chinese silk production centers were located in the northern regions, southern regions, the Sichuan Basin, and Xinjiang. While textiles and

The Textile Museum Collection 2021.17.2

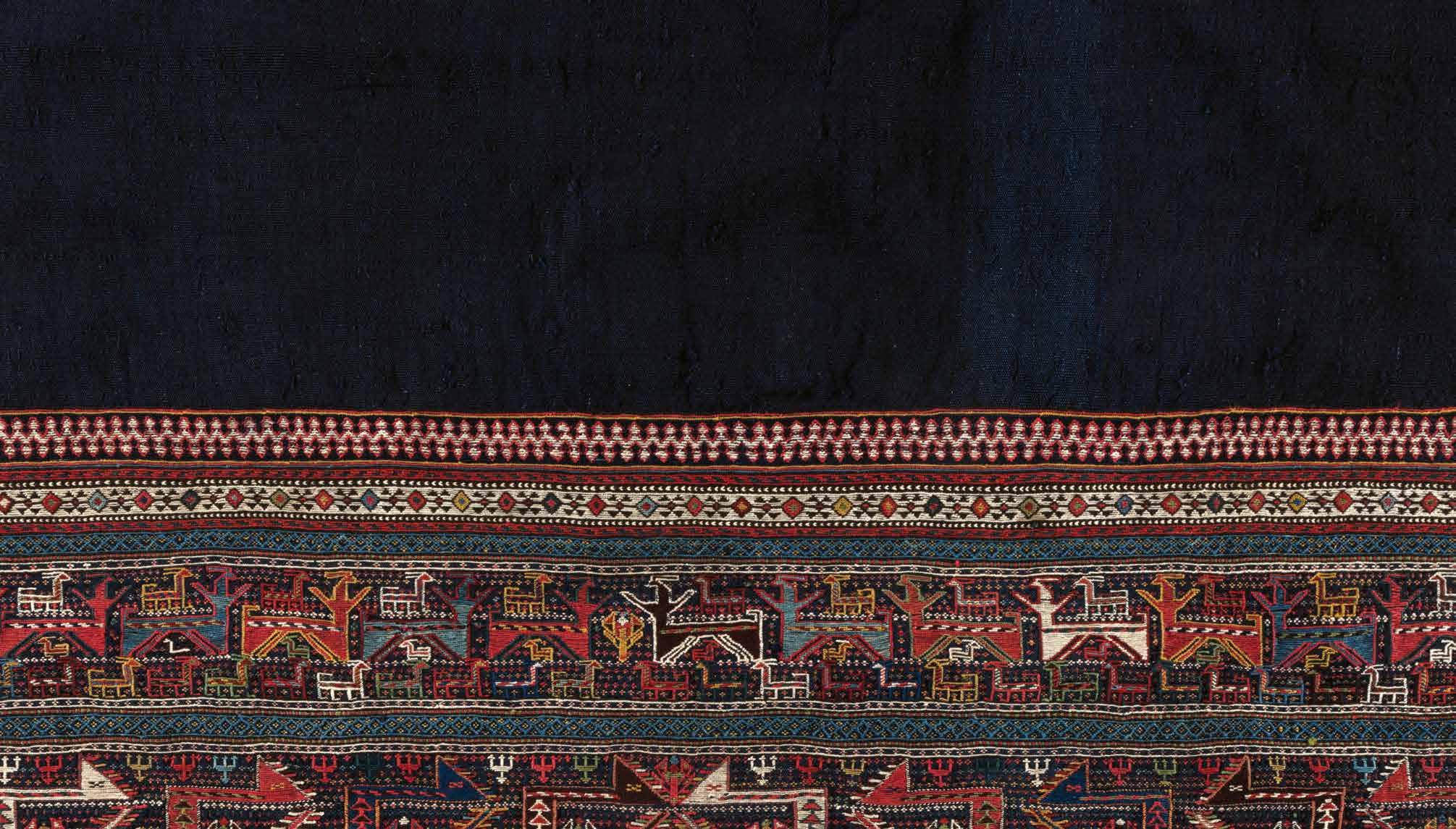

Plate 2, cat. no. 41

Horse blanket

Tibetan Plateau

Late 19th century

Brick Freedman Collection

19th century

Textile Museum Collection 1961.39.13

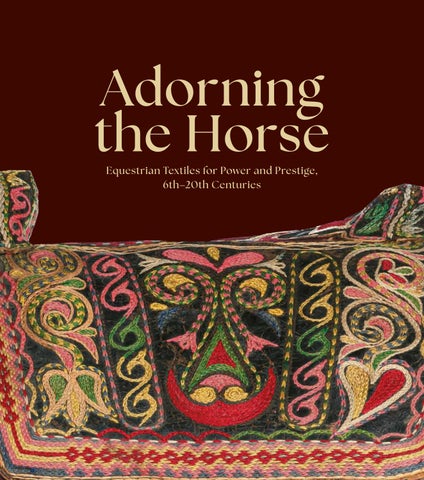

Plate 12, cat. no. 5

Under-saddle cloth

China, Ningxia

The

Gift of Arthur D. Jenkins

Lee Talbot

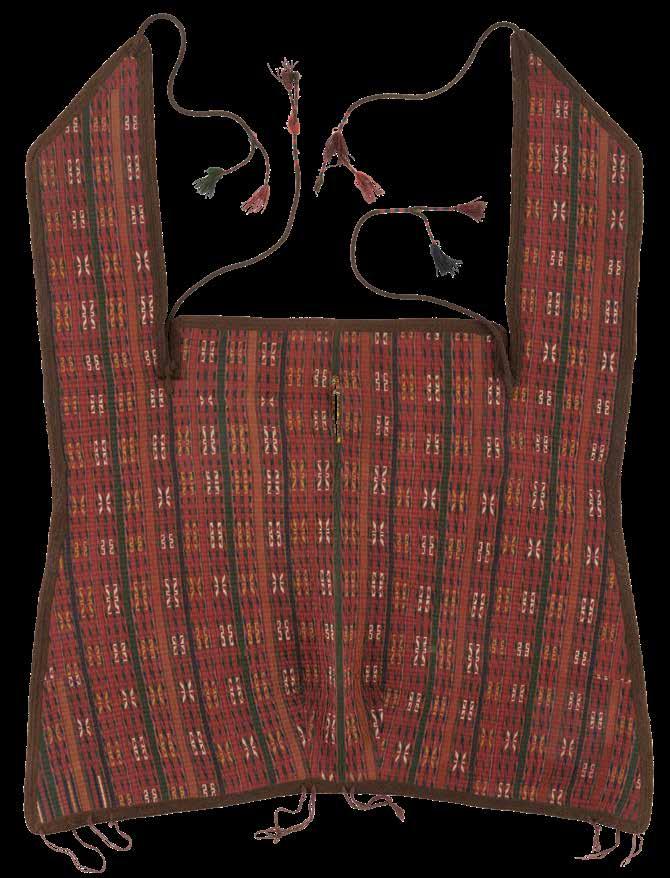

For millennia, horses helped shape the social, political, and economic environments of peoples throughout East Asia—a geographic and cultural region encompassing presentday China (including Xinjiang and Tibet), Japan, Korea, and Mongolia. Until the advent of steam and internal combustion engines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, horses were fundamental in transporting people, objects, and ideas across the region, and in forging and maintaining political entities. People throughout East Asia equated fine horses with wealth, power, and prestige—a notion reinforced by adorning horses with costly textiles and other colorful trappings.

The Textile Museum’s East Asian collections currently include approximately sixty objects created for equestrian use in northwestern and western China, the Tibetan Plateau, and Japan. More than half of these are from the Brick Freedman collection, the donation of which expanded not only the quantity but also the temporal and geographical scope of the museum’s equestrian-related holdings from East Asia. Together, these provide a broad overview of techniques, styles, and social contexts associated with equestrian textiles and cultures in these areas of the world.

noRthWest AnD WesteRn chinA

Horses were introduced to the settled agrarian Chinese by nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples living to the north and west, probably around the end of the third millennium BCE 1 Over time, horses became indispensable for transportation and trade as well as the administration and defense of the vast Chinese empire.2 During the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE), the steady onslaught of mounted invaders from the steppes forced the Chinese to adopt new equestrian military practices such as the utilization of chariots and cavalry as well as new styles of dress suitable for horseback riding.3 Until the end of imperial rule in the early twentieth century, the Chinese relied primarily on neighboring peoples to supply them with horses, but they changed world equestrian history with innovations such as stirrups, which greatly enhanced a rider’s stability and control,4 and the so-called “post-house system,” which accelerated travel and communication by establishing stations that provided fresh horses at regular intervals along major thoroughfares.5

In China, as elsewhere, fine horses were closely associated with high social status. As early as the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), sumptuary laws defined the different types of horses permitted to a ruler and his officials of various ranks.6 Imperial hunts on horseback, often commemorated in court paintings, were symbolic demonstrations of imperial power and military prowess,7 while the connoisseurship of fine horses became a distinguishing hallmark of a gentleman and a social skill discussed in Chinese scholarly discourse for millennia.8 The Chinese developed a wide range of textile forms to be used on horses for comfort, practicality, and display. Although relatively few equestrian textiles from dynastic China have survived the hard wear and tear to which they typically were subjected, visual and literary records such as paintings, sculptures, and period writings can help to build an understanding of the many types used over time.9 These sources document horse coverings and equestrian-related gear made of embroidered silk, animal skins, felt, and other materials, but most extant examples are made with knotted wool or silk pile on a cotton foundation.

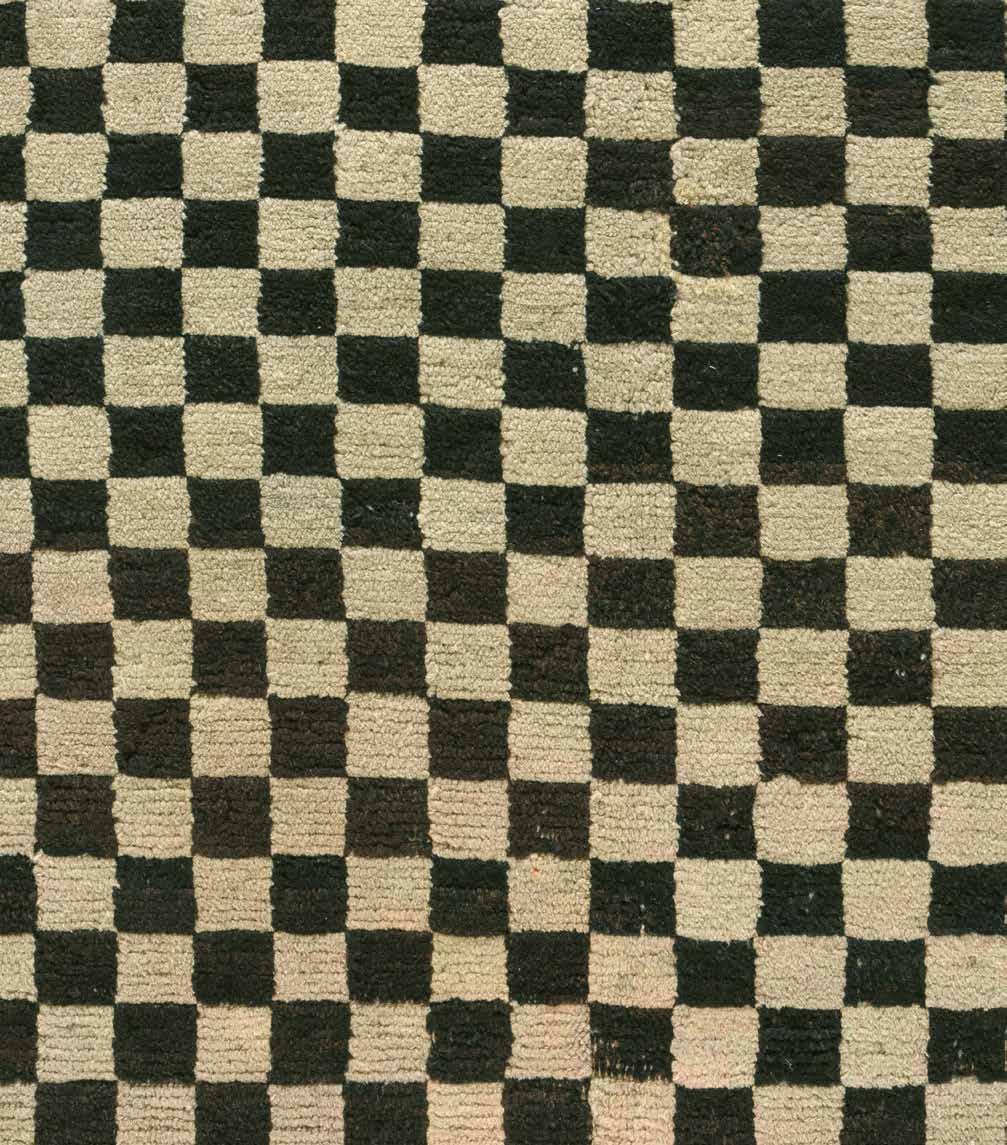

Second half 19th century

The Textile Museum Collection 2021.17.4

Brick Freedman Collection

Plate 21, cat. no. 43

Horse blanket

Iran, Farahan, Arak

ornament in place appear to be gold- and jewel-encrusted, with a gold and jeweled falconer’s drum hanging from the saddle. In contrast to the generic rendition of the prince, the portrayal of the horse suggests that the artist had a specific royal stallion in mind.40

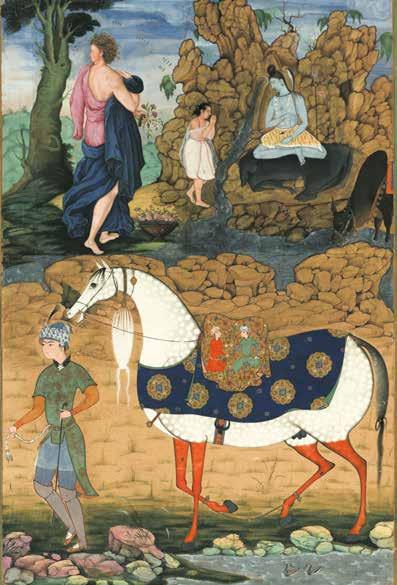

Like the two previous paintings in which the horse in the foreground dominates the overall composition, another painting from the Gulshan Album—indeed, the facing page to the one ascribed to ‘Abd al Samad (Figure 5.6)—may also date to the early Akbar period (Figure 5.8).41 In this painting, there is a seeming disconnect in subject matter and a stark contrast in style between foreground and background, the latter clearly Mughal and the former, depicting a horse preceded by the figure of a courtly page, of Persian inspiration. The page, richly clad in Safavid style, holds a staff and stands on one foot, as though he has been waiting. The large white dappled stallion is hobbled, awaiting its rider, perhaps like the page. It is covered by a brilliant blue blanket decorated with golden rosettes, topped by a saddle cover decorated with a pair of figures on a golden ground that relates to later sixteenth-century Safavid textiles and painted depictions of figures clad in such textiles. Perhaps most striking, the horse’s legs are red as though dyed with henna, a common practice in Iran and Mughal India.42

One last painting from the early years of Akbar’s reign, c. 1570–1575, ascribed to Mah Muhammad, a court painter, seems a standard type of horse and groom painting, but here the running figure with his axe and dagger leading the prancing steed may have a

Fig. 5.8 Horse and Groom, from the Gulshan Album (Murraqa Gulshan), artist unknown, India, second half of the 16th century. Golestan Palace Library, Tehran, No. 1663, fol. 150. Image copyright Golestan Palace World Heritage Complex.

Fig. 5.9 Royal Horse and Runner, attributed to Mah Muhammad, India, second half of the 16th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art 25.68.3, Fletcher Fund, 1925.

Fig 5.8

Fig 5.9

militant role (Figure 5.9).43 The blue-gray dappled stallion wears a blue and gold blanket with orange fringes that appear to sway with the horse’s movement, while an orange cover decorated with gold seems to have been displaced. The front hooves picked out in gold suggest that the horse was shod with gold-plated shoes of the type noted above in the 11th-century Tarikh i Bayhaqi. Clearly this is an imperial stallion, one of the very large number of horses kept in the royal stables according to the Ain i Akbari, an administrative account from the reign of Akbar, written c. 1590 by Abu’l Fazl, the court historian.

Beginning the section on the royal horse stables, Abu’l Fazl notes that Akbar has a “great fondness for steeds … which are a major means for world conquest and

Fig. 5.10 Portrait of the Stallion Dil Pasand, the Horse of Dara Shikoh, attributed to Manohar, India, c. 1630. British Library, IOI Johnson, B20056 81, J.3,1. From the British Library archive.

Fig. 5.11 Horse and Groom, attributed to the court painter(s) of Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah, India, Deccan, Bijapur, c. 1600. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.88 1965. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

consolation.”44 Of the 12,000 horses in the stables, some were brought to court by foreign merchants from Iran and Central Asia and others came as gifts. The finest of these were Arabian and Persian steeds. Abu’l Fazl indicates that their adornment when ridden by Akbar, and the types of jewels and fabrics used, would be “too long and difficult to describe,” although he does note the overall costs of their paraphernalia.45 The four paintings described previously perhaps help to fill in visually the missing details of the text.

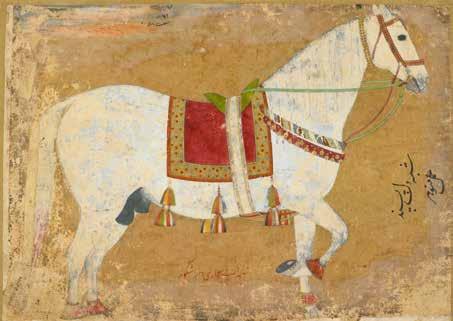

Singular horse paintings continued to be produced under the Mughals through the seventeenth century, some of which were intended as portraits, as they include identifying inscriptions. For example, a large painting of a white stallion by the court artist Manohar, c. 1630, is identified as Dil Pasand (Heart-Pleasing), while another inscription indicates it is “a likeness of the riding horse of Dara Shikoh,” a Mughal prince then about fifteen years old (Figure 5.10).46 The horse is covered by a red saddlecloth with a decorative border and dangling tassels, a small green cushion on top held in place by a strap underneath and by a red band across the chest decorated with what appear to be small golden bells. The tack, which seems eminently suitable for a teenage prince, is further enlivened by red collars at the fetlocks.

The genre of horse painting spread beyond the Mughal court and was adopted in the Deccan, including the kingdom of Bijapur. A painting of an elaborately caparisoned Arabian being held by a groom was likely made at the court of the ruler of Bijapur, Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah (r. 1579–1627), c. 1600 (Figure 5.11). Literally covered with gold ornaments on its bridle

Fig 5.10

Fig 5.11

The Textile Museum Collection 2021.17.5

Plate 45, cat. no. 44

Horse blanket Afghanistan 1890–1910

Brick Freedman Collection

178 Plates