At a moment near the end of her 1988 show Walks on Water –when, after great anticipation, a magnificent waterfall with real running water has appeared, spanning almost the entire width of the stage of London’s Hackney Empire – we see Rose English in front of it fiddling with a little torch. Apparently it will not switch on. ‘What an irritating little prop!’, she says in mock bad temper.

It is fascinating the way a small incident like this can be so revealing about Rose English’s style, and her work in general. Did she contrive it? Did it happen the previous night too? Or is she showing grace under pressure? Either way, we feel she is aligning herself with a long tradition of stand-up comedy where recovery from a failure becomes an integral part of the performer’s poise and wit. By referring to the torch as a ‘prop’, she immediately signals that she is both in the action and knowingly observing it from outside, and her irritation, whether real or feigned, also connects her to an attitude – which we might call ‘English’ in a convenient double sense – of ironic distance from an over-zealous or over-earnest identification with a literal notion of the real. Beyond all this too, we suddenly realise that the little incident plays into an abstract or philosophical theme that has run through the entire show, which has been consciously announced at various points as well as emerging in all kinds of impromptus, asides and improvisations.

For Walks on Water was partly a meditation, debate or quest concerning the relationship between infallibility and fallibility. It was posed as a timeless dilemma, but also as a key to the sociopolitical climate of the time, when the entrenchment of ‘there-is-no-such-thing-as-society’ Thatcherism left many feeling powerless to effect, or even imagine, an alternative future. Fact and fiction take on an intricate reciprocity in Rose English’s work. She plays constantly with the tension between what ‘really’ happens on the stage and the conventions of theatrical illusion and, by implication, projects this play of fact and fiction into the outside world in which we all have to act.

Walks on Water comes about halfway through the body of work this book explores. It was the first time Rose English appeared on a large-scale proscenium stage, working with a host of collaborators and employing for her own ends the lighting, machinery and accumulated lore of a great theatre. Walks on Water had been preceded by a long

series of solo performances in comedy clubs, alternative art galleries and fringe theatres. Originally trained at art college, not at drama school, she developed one of the finest, most original and complex art forms to emerge from avant-garde activity since the early 1970s, an art form which is still evolving and highly influential. Entirely her own invention, there is no convenient term for it. Rose English has never repeated a successful act, or rested with a signature formula, but has always moved on into new realms. As this has happened, the terms used to discuss her earlier work have inevitably come to seem limiting and typecasting. However, one term has been thrown up over the years which does describe her method accurately, or perhaps mischievously, enough to serve as an introduction to her work: ‘abstract vaudeville’.

Abstract vaudeville: the term should really be left alone to act on any reader as it will. Its joining of two unlikes is enough to bring about a chain of reflection. There is immediately the danger of a heavy-handed explanation of something light and mobile, which flashes from the ephemeral moment. In many ways English herself has reflected continuously on the marriage of entertainment and philosophy that she has brought about from within the work itself, delivered from inside some gorgeous costume. Or, on other occasions, she has made sure that others within the cast have brought her high-flown thoughts down to earth, or have demonstrated in their actions the paradoxes she has conjured up in the mysterious attractions and repulsions between words. Suffice it to say that Rose English knows how to be light and profound at the same time. Her work is full of humour and fantasy but also deals with the most difficult philosophical problems and dilemmas of life and behaviour. Revelling in its metaphor of theatre, it can deploy both a fairy-tale magic, the whole possibility of the dramatic arts to suspend disbelief, and a penetrating irony which cuts through pretence and sham. In other words, her art is poised on the borderline between playing and being. The grievous consequences of fakery and deception, on the one hand, are played against the imaginative dream and aspiration on the other, often in the same gestures and scenes.

So, on one side, vaudeville and all its associations: a show, a spectacle, a great night out, comedy, revue, musical, music hall, show on ice, Folies-Bergère, cabaret,

‘That I may not utterly defraud the reader of his hope, I am drawn to give it these brief touches, which may leave behind some shadow of what it was’1

— Ben Jonson, 1606

circus, magic and pantomime traditions. On the other side the intellectual adventure of modern art, which has created through its pursuit of the abstract a new space for thought and feeling, a ‘void’ of unconditioned meaning and possibility. Of course, if the history of the modern arts is attended to carefully it will be found that these two streams are not the opposites they appear to be but have instead interpenetrated continually. Fernand Léger was only one of many artists who married the energy he found in circus, dance hall, street fashion and speech with a high level of abstraction. Cabaret, for example, has been alternatively, or simultaneously, popular entertainment, scathing satire, and avant-garde literature. Rose English, for her part, once described her work as occupying a mid-ground between Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, the 1954 film with lyrics by Johnny Mercer and music by Saul Chaplin and Gene de Paul, and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23) by Marcel Duchamp. ‘Both have profound truths in them’, she has said.2 She often mentions Tommy Cooper as her favourite revue performer. She calls him in fact the Marcel Duchamp of comedians because both are ‘deeply abstract’.3 Art history has probably yet to explore a connection between Tommy Cooper’s little gate on stage, with nothing on either side, which he would open and go through to begin his act, and Duchamp’s corner-positioned Door – 11 rue Larrey (1927) which can be both open and closed at the same time. There is a curious affinity in their philosophical properties and their closeness to the absurd, between the ‘joke-shop aesthetic’, as English calls it, of Cooper’s startling array of homemade

Notes made by English at the same time (when she was performing in Potter’s film Thriller, shot in 1979) show an intense interest in the nature of acting and where the transition point is between acting and non-acting. If one was not attempting characterisation but was thinking more in terms of a mode of being, on stage or in front of the camera, was one acting, was one posing? How is skill applied to the task? How is meaning evoked through the way a gesture is executed? Special experiences are produced by film acting, such as the shock of recognition when seeing the image of oneself: it was the self but ‘removed from the idea of one’s own “self-image”’.28 All these were new experiences for someone with a visual art rather than a theatrical training. But in their rawness they reflected a condition which was characteristic of performance art from its inception: the uncertain borderline between being oneself and acting a role.

When considering the ambition and intellectual energy of experimental artwork in the 1970s, it is often forgotten the tiny budgets on which most of this art was produced. Grants were available but it was difficult to get more than minimal support for something that was expressly conceived to take place outside institutional and commercial frameworks, or to operate between conventionally accepted genres. A considerable number of artists lived in telephone-less squats, so that every small administrative detail of a production meant a trip to the local phone box with a bag of coins. In the ‘materials’ section of the budget for the three-venue performance, Berlin (1976), even the

coal needed for the fireplaces in the squat which forms one of the scenes was listed:

Materials: costume hire (7 frock-coats for 3 weeks), £56; costume details (shoes, collars, studs, handkerchiefs, etc), £40; cradle and matching crinoline skirt, £12; 2½ cwt. coal (12 domestic fires, 4 nights @ 3 fires per night), £5; 1 black silk dress (secondhand), £3; 1 black silk chinese suit (second-hand), £4; 1 pair ice skates, £5; 1 cwt. block of ice, £1.50; tapes, £4; records, £7.29

English’s early ‘minimalism’ was dictated as much by the budget as by aesthetics and conveyed an abbreviated magnificence. The cradle floating on the ice in Berlin was inspired by the fantastically ornate sleighs on which King Ludwig II of Bavaria spent part of his state budget. The irony of producing the spectacle on a shoestring has always been part of English’s shows.

In funding application letters for Berlin, English and Potter outlined their need for ‘performing contexts free of theatrical expectations or art-world centralism, and the need to make some work which made use of our activities in parallel areas within a coherent whole.’30 These contexts would be chosen for ‘their contrasting qualities and functions (private, public and institutional spaces)’, and they expressly stated that ‘the work shall be made to the same criteria of subtlety and professionalism that recognised contexts (i.e., theatres, art galleries, etc.) demand’.31

The English/Lansley/Potter collaboration progressed in varying configurations. Berlin was staged and performed by English and Potter in three London venues –their large squatted Regency house in Mornington Terrace, NW1; the Sobell Centre Ice Rink; and Swiss Cottage Olympic Swimming Pool. Mounting (1977) was created and performed by all three at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford (MOMA, now Modern Art Oxford). The film Thriller was directed by Potter and shot in Northington Street, London in a later squatted house shared by English and Potter. English acted in Thriller, and co-wrote the script for The Gold Diggers (1983) with Lindsay Cooper and Sally Potter; she was also the film’s art director. Financed with a British Film Institute award and starring Julie Christie, The Gold Diggers established Sally Potter’s international reputation as a director. The following remarks will concern English’s early ‘ground-breaking’ work as she experimented with ideas that would recur as key features of her later works.

Some have already been mentioned. Berlin contains a commentary within the work on the progress of the work itself (like Rabies) and refers to arguments the protagonists had had earlier in the day about ways of reading and interpreting the imagery they had constructed. At one moment in Berlin, Potter, standing under a naked lightbulb, unrolls a scrolled photograph taken of English standing under the same lightbulb in a previous episode, with tears rolling down her face. The dispersal of the venues around town and the week-long gaps between the four performances which make up the work also fuelled English’s interest in the

Berlin, 1976: Research and development / 038 Postcard of an eighteenth-century sledge, Marstallmuseum, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich | 039 Postcard of Diego Velázquez, Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Pink Dress, 1660 | 040-041 Two-page funding application to the Arts Council Performance Art Committee

processes of remembering ephemeral phenomena which come to play such a large part in The Double Wedding Berlin introduces an all-male chorus, to be seen again 12 years later in Walks on Water (1988). In Berlin the men are standardised and silent, acting as a somewhat mournful group that skates over the ice or descends slowly into the swimming pool, and comes out again dripping wet. At one point their silent presence continually disturbs a monologue about the representation of women in the piece.

Generally [the men] did epitomise a feeling that we had at the time about what men needed to do now that they were starting to hear about feminism. We had observed them being lost and not knowing where to turn for nurturance and succour… They needed to turn to each other. The decision to reverse history and place men in the background to the main action was consciously taken.32

The men’s faltering presence contrasts strikingly with the way English, Lansley and Potter viewed their own collaboration at the time they were preparing Mounting, a year later in 1977.

Down the slope they rolled in a trio, spilling the beans as they passed the tufts, opening the doors on the station platform, stepping into the light and spreading the tales, opening history and speaking in threes.33

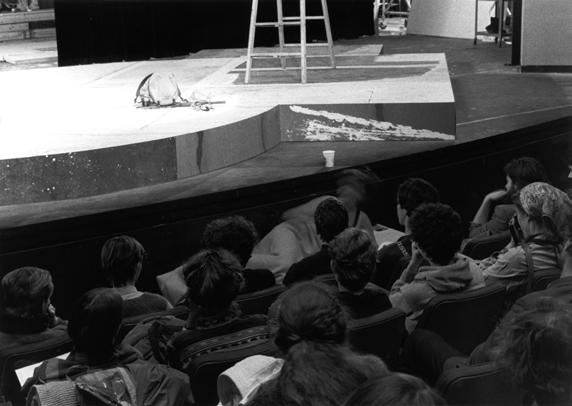

175 Rose English, Hackney Empire Photographic Collage, 1987 |

177 left Unknown artist, Old Sadler’s Wells Theatre Audience, early eighteenth century, etching with watercolour, British Library |

177 right George Cruikshank, Mrs. Liston as Queen Dollalolla, 1817, hand-coloured etching, British Museum | 178 The forest scene from Act 2, Walks on Water, 1988

English’s next works were to show a huge expansion in just about every aspect that had been announced embryonically in the solo performances and first collaborations. Between 1988 and 1994 she staged three major productions at London theatres: Walks on Water (1988) at the Hackney Empire, The Double Wedding (1991) and Tantamount Esperance (1994) both at the Royal Court theatre. Not only did they exchange art venues and alternative theatrical spaces for full-scale proscenium stages, but there was a corresponding quantum leap in the scale, and often the ambition, of props and scenery, costume and lighting, the contribution of collaborators, and the nature of the scripts. Walks on Water was the first performance in which the artist worked with the designer Simon Vincenzi and the musician/composer Ian Hill, in what was to become a vital creative collaboration. They went on to work together on English’s The Double Wedding and Tantamount Esperance. Ian Hill also composed the music for The Nature Table – a pets opera (1995), Standing Room Only – an opera of the ordinary (1999) and the work in progress Rosita Clavel –a horse opera (from 1997). Many other performers and collaborators joined the ‘company’ too: in The Double Wedding English calls them ‘consorts’. In each case the specificity of their roles and appearances revolved around and emanated from their personal individuality. In turn, the cast of collaborators developed the complexity and depth of English’s own stage persona.

An avant-garde innovator going back to the proscenium theatre? It might sound like a retreat, especially as English has said she found herself drawn to some of theatre’s ‘most arcane’ conventions.110 But to judge this a retreat would be to miss her humour and complete freedom from academicism. After all, by this time the avant garde was already setting up its own academy of codes and conventions – just as assuredly as the years of dust that had settled over traditional theatre could be brushed off to reveal extraordinary jewels. In English’s work all adoptions and critiques of past theatrical, opera, ballet and popular traditions, as well as the contemporary avant garde, are done with humour, a feeling for the absurd mixed with a tender respect – above all with a sense of complexity. Exploring the history of spectacle, she felt a simultaneous attraction to the illusion and the backstage world of pro-

ducing it, a symbiosis carried to extraordinary lengths in the architecture of the great metropolitan theatres. The vast gilded hive of the Paris Opéra’s Palais Garnier, for example, contains five floors under the stage and five floors above it. The two sides of the symbiosis are also expressed in the stark contrast between florid decoration and practical machinery: English was once given a guided tour of the building by the technical manager and later inspected the magnificent model of the Garnier on display in the Musée d’Orsay. Her own parallel professional activity over the years of appearances in other people’s work – in dance, opera, films and plays – gave her further insight into backstage and off-camera behaviour which came to be incorporated into the very structure and scenarios of shows like The Double Wedding and Tantamount Esperance.

Of equal interest to English is the multiplicity of contexts in which the ‘show’ can manifest itself – from the agricultural county show paddock to the ice-spectacular, from the Vienna Riding School to Las Vegas neon, from the IMAX cinema to the primary school ‘nature table’. And then there are the ways in which ancient skills – the balance of the acrobat, the sleight of hand of the magician, the selfabsorption of the musician, the agility of climbers on an indoor rock-face – become theatricalised as an event for witnesses. There is also attention to performance space at its most basic and primordial – in the arena, for example. Theatre form and history are only one element in the noholds-barred interdisciplinarity that lies behind each of Rose English’s performances.

There were perhaps two chief aspects of theatre history which English set out at this time to discover beneath the dust: one social, the other – and I think there is no better word – cosmic. Both come down to us as the memory traces of something that has vanished: on the one hand an extraordinary social vigour – ‘an Elizabethan public theatre cast its spell over a truly popular audience, representative of all classes of society’111 – and on the other a sense of the awesome and marvellous.

Fifteen years ago our theatres were tumultuous places: the coldest heads became heated on entering, and sensible men more or less shared the transports of madmen.112

Your stinkard has the self same liberty to be there in his Tobacco Fumes, which your sweet courtier has: and… your carman and tinker claim as strong a voice in their suffrage, and sit to give judgement on the play’s life and death, as well as the proudest momus among the tribe of critic. 113

The scripts may survive, a spruce and orderly replica of the Globe Theatre may be constructed on or near its original plot of land beside the River Thames in London, daring liberties may be taken with the staging of the classics, but we cannot find that lively audience again, and its dialogue with the play. Or, to put it more precisely, it is only the rumbustious language and images of the time (either verbal or graphic) which convey to us, and even helped to create, the phenomenon of sociability that the theatre audience once was. The writers themselves were usually aware of the human nature of this frail contract, as seen in this essay’s epigram from Ben Jonson: ‘That I may not utterly defraud the reader of his hope…’ Theatre: from the social to the cosmological.

The spectacle lasted twenty-five days, and on each day we saw strange and wonderful things. The machines (secrets) of the Paradise and Hell were absolutely prodigious and could be taken

by the populace for magic. For we saw Truth, the angels, and other characters descend from very high, sometimes visibly, sometimes invisibly, appearing suddenly. Lucifer was raised from Hell on a dragon without our being able to see how. The rod of Moses, dry and sterile, suddenly put forth flowers and fruits… We saw water changed into wine so mysteriously that we could not believe it, and more than a hundred persons wanted to taste this wine. The five breads and the two fish seemed to be multiplied and were distributed to more than a thousand spectators… The eclipse, the earthquake, the splitting of the rock and the other miracles at the death of Our Lord were shown with new marvels.114

The changing of scenery, trap doors, the ways to represent Hell, a conflagration, the sea, boats, clouds, fountains, wind, a constantly flowing river, thunder, lightning, transformations – these were the ever-recurrent problems that stimulated the ingenuity of the Renaissance ‘technical director’.115

But that, which (as above in place, so in the beauty) was most taking in the Spectacle, was