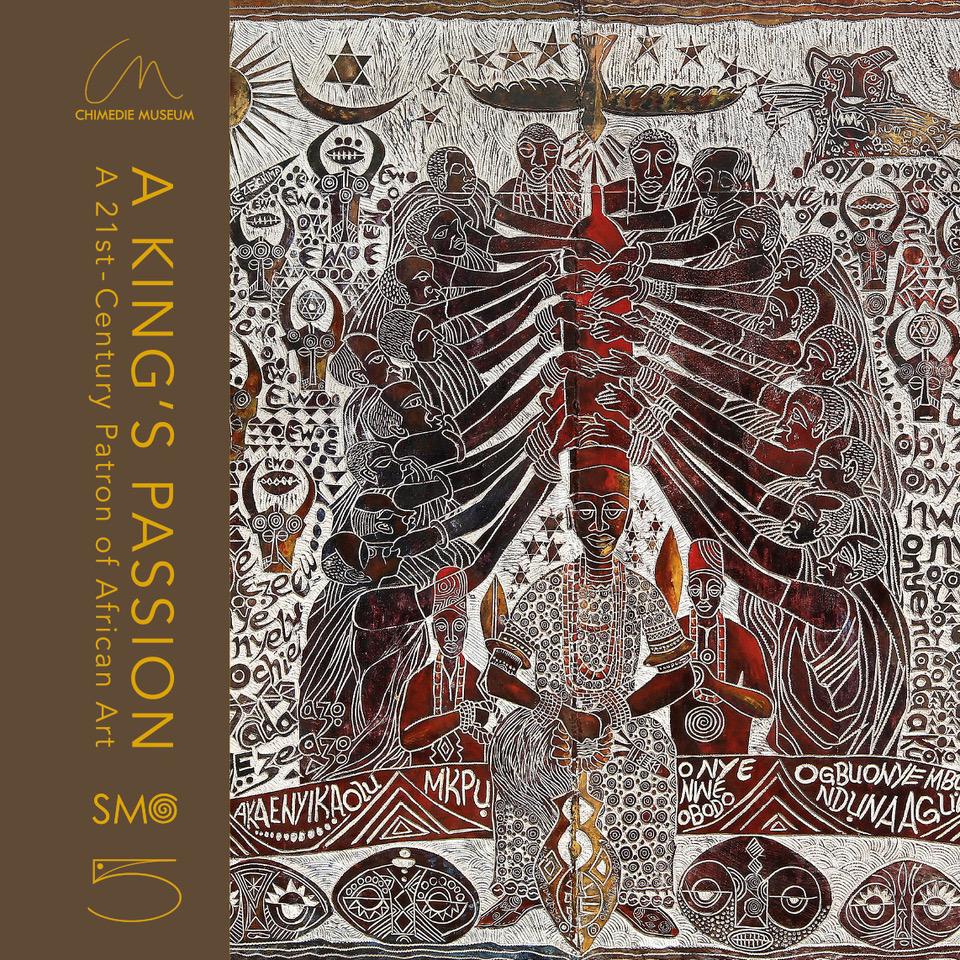

Breaking Stereotypes Through Art Collecting

Access Bank Corporation is committed to redefining the African narrative and image of Africa by celebrating the continent’s potential for sustainable development and economic growth. We are therefore delighted to sponsor A King’s Passion: A 21st-Century Patron of African Art, which strategically shows how art can contribute to developing our continent and telling a fresh story with ancient roots. The impact of HRM Nnaemeka Alfred Achebe’s exquisite art colllection of traditional and contemporary art, and his strategic art patronage, for over 40 years nurturing African talent, is a beautiful example of how creativity can create wealth from the grass roots all the way up through society, and create important paradigm shifts about our identity, our culture, and our history.

Access Bank’s strategy for achieving economic sustainability includes harnessing the potential of Africa’s creative industry, through investing in our own growing art colllection, and supporting initiatives like the yearly Art X Lagos art fair and Access Bank Art X Prize, the African International Film Festival (AFRIFF), and the Born in Africa Festival, which all contribute to bringing the power and ingenuity of African creativity to a global audience.

A King’s Passion confirms that collecting art and supporting artists through private museum colllections challenges negative stereotypes about Africa. This is an exciting story about the critical role art patrons play in expanding narratives, contributing to critical global discourse, and ensuring that we protect and project our histories and artworks while nurturing our creative soul for generations to come. His Majesty’s generous patronage has paved the way for leading and emerging artists to be recognized and celebrated both at home and abroad.

The rising prominence of African art in the global space is as a result of the enthusiastic passion and generous patronage of African collectors like HRM Nnaemeka Alfred Achebe, who continue to inspire and encourage artists and give them wings to fly. Access Bank affirms that we will continue to support publications and iniatives like A King’s Passion, which make us proud of our heritage.

Herbert Wigwe Group CEO Access Holdings

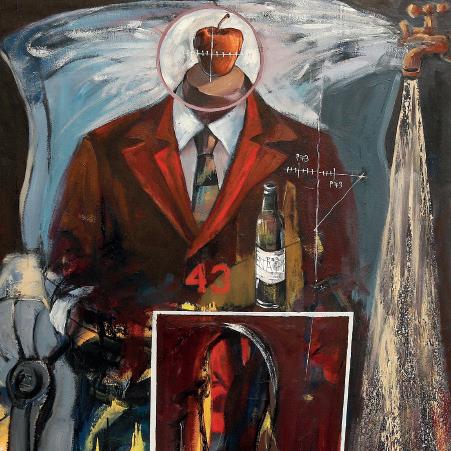

George Hughes

Probable Futures, 2005

Mixed media

170 × 120 cm

The Journey

Introduction

It is with great gratitude that I reflect on the privilege of working with the Obi of Onitsha, His Royal Majesty Igwe

Nnaemeka Alfred Ugochuwkwu Achebe CFR, whom I fondly call “HRM Agbogidi”, on the journey of this book and the Chimedie Museum Collection. He is one of the greatest collectors I have worked with, whose passion for art has depth and breadth.

It is easy to appreciate Agbogidi’s patronage of the arts. He has traveled many miles and invested exemplary effort and time to uplift artists all over the continent. On every official trip he takes, he finds time to connect with the artistic community of the place he visits. Working with him over the years has been a deep dive into the incredible wealth of African art. His colorful stories of encounters with artists, young and old, show a fatherly patron who takes his role as Custodian of Culture and Creativity to heart. Many artists have been touched and inspired by his genuine interest in their expression and creative journey, and I have seen them “glow and expand with pride and excitement” during an encounter with him.

In this brief essay, I would like to share some highlights of the past few years documenting Agbogidi’s collection and shed light on a visionary custodian whose collecting started with a small work gifted to him during the Biafran War in the late 1960s. He met the legendary Professor Uche Okeke, best known for showcasing the importance of Igbo traditional Uli aesthetics for global recognition, who gave him a small print called Exodus. “It was a typical Uche Okeke with pen and ink on paper, depicting a community in flight from a combat zone, their belongings on their head, and in obvious grief. That was my first Nigerian artwork,” Agbogidi told me during an interview in 2020 in his residence in Onitsha.

From this small historic print, which was unfortunately lost in later years, he has grown his collection to over four thousand exquisite and rare works of art.

The Background

To understand the root system of my contact with Agbogidi, I have to trace my connection to the friendship he had with my late father, architect Frank Nwobuora Mbanefo. During one of my many chats with Agbogidi, he told me how my father’s pitch, for an architectural competition for a multinational

Gerald Chukwuma Untitled Mixed media panels

Chimedie Museum: The Custodian of the People’s Culture

Every human society, civilization, and culture preserves a unique salvation narrative it uses to inspire its people in times of extreme difficulty and socio-political upheaval. This myth, folklore, history, or urban legend often chronicles the life and example of a savior figure or avatar imbued with the spiritual, political, or military authority to deliver the people from bondage. A deus ex machina ordained by cosmic powers to break the yoke of oppression or liberate the masses by charting a new path for the nation through divine charisma and a far-sighted vision. In the Far East, these qualities of leadership would traditionally be identified by a supernatural proficiency in the martial arts as a spiritual endorsement that was often associated with that particular art form. The integrity applied to performing the movements, postures, and forms of the given discipline (be they Yoga Tai-chi or Kung-Fu) were the yardsticks for determining divine approval. An old man of eighty may by this presentation easily outwit a much younger, stronger opponent in a dual or demonstration on account of his superior mastery of the rudiments and deep practices of the given art form.

The underlying message from this salvation narrative thus suggests that “right makes might.” In another salvation narrative from Kano and other emirates of northern Nigeria, the Durbar festival held once a year articulates an alternative vision of right-choice-ness. At this colorful ceremony, the Emir or traditional ruler is known to sit outside motionless on his throne as horsemen from all the noble families of the land charge directly at him one after the other. Dressed in full battle regalia and armed for mortal combat, they gallop ferociously towards their seated lord in pincer formation while chanting fearsome battle cries and brandishing their deadly weapons of war. As they approach the throne, the horsemen slow to a canter and veer off to the flanks as a show of allegiance. This re-enactment of a battle scene demonstrates the controlled force and power at their king’s disposal and graphically illustrates the people’s loyalty to the Emir. The ceremony shows their military union with their ancestral throne and heritage through mastery of equestrian elegance, military power, and controlled aggression.

Reversing the presentation of the martial artists of the Far East, this salvation narrative may seek to embrace the notion that “might makes right”.

Umoh Akanimoh Jahban Christ, 2012 Oil on canvas 90 × 90 cm

. . . as a Dream Deferred Becomes that Very Dream Fulfilled . . .

Usually, in the art world, some of the most salient questions at stake revolve around ideas of what we are doing; why we are doing what we’re doing; and for whom we are doing what we do. One has often wondered why people choose to collect art. What would be the motivation for this sort of activity? To what extent would we consider it as a fluke? To what extent would we consider it as an obsession? And to what extent are we to imagine it as a social service?

If we were to consider this gesture of art collection in the larger scheme of things, we would say that the artist’s career is probably receiving some very necessary support through patronage and that the collector becomes an essential catalyst in the development of the artist’s vocation. And if even the initial impulse for the collection, however, were to be premised on the decoration of one’s apartment or home, we would soon realize that, even in that respect, one quickly runs out of wall space. What becomes of the essence now is the need for more space, because once the drive toward acquisition of artworks has been established, it is quite difficult to give it up. The collector would best be described as obsessed.

Suddenly, the possibility to expand the argument or motivation for the collection beyond the immediately personal becomes imperative. The collector’s obsession leads to other publics who would have to somehow get access to the collection too, that is, if the owner of the collection is able to create the condition for this kind of sharing. An institution would, as of utmost importance, have to be founded. This institution then initiates the activities that lead to the mediation of access. In this sense, it is possible to propose that the one who is collecting art is making a most significant contribution to the inscription of collective history. The collector is therefore arguably a crucial agent in the development of the collective cultural consciousness. Yet, at the center of all this are the artists and the works that they produce. For it is the artworks, after all, that make up the collection. The story of how His Royal Majesty, Igwe Nnaemeka Achebe, the Obi of Onitsha (Agbogidi) came to art collecting is fascinating. It sounds as though the current materialization of the Chimedie Museum becomes the manifestation of a dream long deferred. As he wrote the poem titled “Harlem” in 1951, Langston Hughes, in commenting on the situation of African-American literary artists in segregationist America, asks:

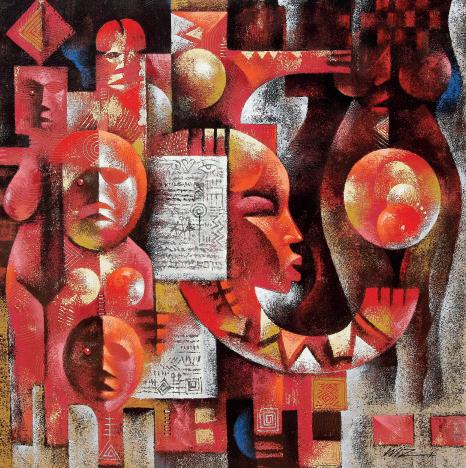

Wiz Kudowor Pro-Creation Spirit, 2008 Acrylic on canvas 120 × 120 cm

Thoughts on the Chimedie Museum and its Royal Progenitor

“That is why we have the Museum, Matty, to remind us of how we came, and why: to start afresh, and begin a new place from what we had learned and carried from the old.”

The above quotation, from the American writer Lois Lowry, quite simply summarizes the essence of the Chimedie Museum and its important place in Onitsha, in Igboland, and in Nigeria. But for me, it does more. It connects to the earliest time I heard about its royal progenitor Igwe Nnaemeka Achebe from a bright and much younger colleague of mine in broadcasting and public relations, and an Onitsha native to boot, Emeka Maduegbuna, back in the 1990s and early 2000s. Emeka is as proud and highly communicative an Onitsha man as they come, who used to fill me in on the goings on in the ancient kingdom. He was excited about the coming of a new king, a new time, and the promise of a great future for Onitsha and Igboland!

In those days, all of us in public relations in Lagos had heard about ‘an engineer’ (sic!), proficiently ensconced in the top echelons of public relations within the oil industry (at Shell,

no less!) who had, what was for me then, the somewhat confusing and intimidating title of executive director and general manager for human resources and external relations!

Phew! It turns out later that this was the same man Emeka had been telling me about with great gusto, whose coming promised a great future for Onitsha. He is now our much revered Igwe Nnaemeka Achebe, Obi of Onitsha, Agbogidi, the royal personage behind the Chimedie Museum, a notable part-fulfilment of that promise of a new Onitsha.

In His Majesty’s letter honoring me with an invitation to be part of this book, Agbogidi said in part what he envisions “The Chimedie Museum, is going to be a vibrant platform for celebrating traditional, modern, and contemporary African art and culture, based in Onitsha.” This reminds me of a promise he made in April 2003, to a meeting of constituent groups in Onitsha, when he proposed an Ime-Obi development project which “will include a museum and resource center as [a] repository for manuscripts, papers, artefacts etc., on our history, culture, and traditions.”

It is not my place at all to say more about this. I am sure that in other more relevant sections of this book, there will

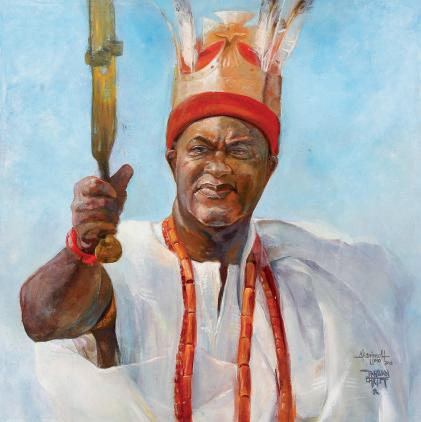

Jude Onah Untitled, 2011 Oil on canvas 97 × 63 cm

While we may bemoan the absence of a solid art infrastructure in Nigeria, nonetheless, we are encouraged by an emerging art ecosystem and the critical role of patrons such as His Majesty Igwe Nnaemeka Achebe in this nascent development.

Agbogidi’s support has been fundamental in grounding and sustaining a range of initiatives that have appeared in the last twenty odd years, including Life in My City Festival in Enugu and the international contemporary art fair, Art X Lagos. More significant is his unwavering support in returning seminal figures in Nigerian art to public memory. The various chapters of modernist and contemporary African art unfold remarkably in his formidable collection. For Agbogidi, collecting is not merely a passion or favorite pastime. Instead, it is a humanist act and a form of social activism; one that insists on the building of a breathing archive of artistic achievements for the benefit of all and for future generations.

Smooth Nzewi Artist, Art Historian & Curator

His Majesty Igwe Nnaemeka Achebe, the Obi of Onitsha, has always been an amazing patron of the arts, and his new museum will be an important asset for his community and for the country. As a dedicated philanthropist, he has been one of the strongest supporters of the art industry in Nigeria. He is a great King and humble Leader to his people, with amazing compassion. It comes as no surprise that he would dedicate such energy to share his art collection with his community, which will serve to inspire, educate, and promote Nigerian culture.

Kavita Chellaram Founder/CEO, Arthouse Contemporary & ko Gallery

Nyornuwofia Agorsor Light Is Hope, 2013 Acrylic on canvas 120 × 100 cm

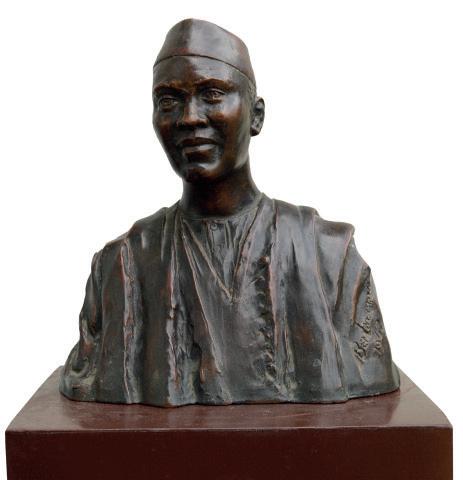

Ben Enwonwu

Bust of Zik, 1962

Porcelain

25 × 20 cm

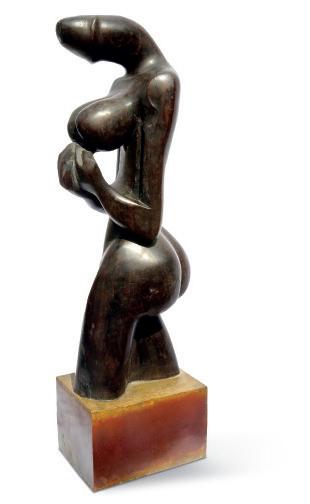

Ben Enwonwu

Untitled Wood

H. 70 cm

Uzo Egonu

Untitled, 1972

Uzo Egonu

Flute Players and Dancers, 1974

Linoprint

51 × 71 cm

Muraina Oyelami Village Sense, 2009

Muraina Oyelami Mythical Animal, 2009 Oil on board

90 × 122 cm

376 Duke Asidere Opinions, 2021

Graphite, charcoal, pastel, Conté on watercolor paper

76 × 56 cm

Duke Asidere New Doors, 2021

Graphite, charcoal, pastel, Conté on watercolor paper

76 × 56 cm

110

88 × 145 cm

< Olumide Onadipe

The Couple and the Virgin, 2011

Acrylic on canvas

× 110 cm

Olumide Onadipe

Lagos Woman, 2012

Acrylic on canvas

5 CONTINENTS EDITIONS

Art Direction

Stefano Montagnana

Editorial Coordination

Aldo Carioli in collaboration with Lucia Moretti

Editing and Proofreading Charles Gute

Pre-press

Maurizio Brivio, Milan, Italy

All rights reserved

© SMO Contemporary Art Ventures / Obi Nnaemeka Alfred Achebe

For the present edition

© 2023 – 5 Continents Editions S.r.l., Milan, Italy

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

5 Continents Editions

Piazza Caiazzo 1 20124 Milan, Italy

www.fivecontinentseditions.com

ISBN 979-12-5460-049-8

Distributed by ACC Art Books throughout the world, excluding Italy. Distributed in Italy and Switzerland by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A. Distributed in France and French speaking countries by BELLES LETTRES / Diffusion L’entreLivres.

Printed and bound in Italy in September 2023 by Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Divion Loreto – Trevi for 5 Continents Editions, Milan