Authors:

Sociological research: Adina Ghiocel-Pascu and Anamaria Dinu

Legal research: Ștefi Ionescu Research assistant: Luca Istodor

Layout & Design: Cristian-Dan Grecu

Graphic elements: Alex Petrican

Translation to English: prof. psih. ing. MA Daniela-Irina Darie

Collaborators: Iustina Ionescu, Alina Dumitriu, Diana Dragomir, Teodora Ion-Rotaru, Florin Buhuceanu, Cosmin Grădinariu, Andre Rădulescu, Ralu Baciu.

Thank you to all of the organisations, institutions and people who supported us in conducting the interviews for the sociological part of the research.

This research was made by Accept Association and ECPI- The Euroregional Center for Public Initiatives, in partnership with Sens Pozitiv, Rise Out, PRIDE Romania, Identity.Education.

Contents

I. GLOSSARY OF GRAPHIC SYMBOLS EMPLOYED IN THE RESEARCH REPORT 5

II. INTRODUCTION 9

Background to the research 9

Objectives of the research 9

Methodology of the Research 10

Stage 1 – qualitative research 10

Stage 2 – quantitative research 10

Stage 3 – legal research 12

III. SOCIOLOGICAL RESEARCH 13

Section 1: Exploring the needs of people living with HIV in accessing the health services in Romania 14

i The medical and emotional pathway of the HIV-positive patient 15

ii Challenges associated with HIV/AIDS 16

iii Coping mechanisms in the interaction with the medical system 20

iv. Circle of trust of the HIV+ person 25

v. The role of NGOs 27

vi. Health services in Romania 28

Section 2: Contextualising the lack of antiretroviral treatment 30

Section 3: Understanding discrimination, prevention, information and the interest of people living with HIV in the context of the legal framework in Romania 33

i Discrimination 34

ii Exposure of the HIV-positive status 36 iii HIV Prevention 38

iv. Impact of Covid-19 41

Section 4: Conclusions of the sociological research 43

IV. LEGAL RESEARCH

45

Section 1: General aspects 46

Section 2: Medical legal framework 55

Section 3: Social protection 65

Section 4: Education system and HIV 68

Section 5: Fight against discrimination 70

Section 6: Confidentiality 74

Section 7: Criminal incrimination 81

Section 8: Conclusions of the legal framework validated by the sociological study 88 V. RECOMMENDATIONS 90

I. Glossary of graphic symbols employed in the research report

Qualitative research stage

This symbol marks that the data in that section results from the qualitative stage of our sociological research.

Quantitative research stage

This symbol marks that the data in that section results from the quantitative stage of our sociological research.

HIV/AIDS Gay person

This symbol marks a discussion around HIV/AIDS or about people living with HIV (PLHIV). HIV stands for Human Immunodeficiency Virus. HIV attacks the immune system and gradually damages it. This means that without treatment and care, a person living with HIV is at risk of developing serious infections and cancers that a healthy immune system would ward off. Current HIV treatment works by reducing the amount of virus in the body so that the immune system can function normally. It cannot get rid of HIV completely, but with the right treatment and care, a person with HIV can expect to live a long and healthy life.

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to a gay person, i.e. a person attracted to other people of the same gender as them (eg: a man attracted to other men, a woman attracted to other women).

Heterosexual person

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to a heterosexual person, i.e. a person sexually and/or romantically attracted to people of a different gender than themselves (eg: a man attracted to a woman; a woman attracted to a man).

Transgender person

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to a transgender person, or trans person. This is an umbrella term that includes those people who have a gender identity other than the sex they were assigned at birth. The term includes those individuals who feel the need, prefer, or choose, through language, terms of address, clothing, accessories, makeup, or bodily modifications, to present themselves differently from the expectations associated with their assigned gender at birth. This concept

6

includes people who have undergone medical or legal transition (people with a trans past), but also people who identify as transgender but do not transition, as well as all those who have a gender identity or gender expression that does not conform to the standard of „male” or „female”.

Drug user

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to drug users. In this research, we focused in particular on people who use injecting drugs, as they constitute one of the categories at risk for HIV infection.

Person who practices commercial sex

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to commercial sex workers, i.e. adults who occasionally or regularly receive money or goods in exchange for consensual sexual services or erotic performances.

Social activists

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to social activists, namely those people who fight for the rights of disadvantaged or discriminated people, such as people living with HIV, LGBTQ+ people, Roma people etc.

Medical staff

This symbol marks a discussion/mention related to medical personnel: doctors, nurses, nurses etc.

Sources:

• Informat HIV, Asociația Sens Pozitiv: https://informathiv.ro/;

• Raportul Trans în România, Asociația Accept: https:// transinromania.ro/trans-in-romania/;

• Understanding Sex Work in an Open Society, Open Society Foundations: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/ understanding-sex-work-open-society

7

II. Introduction

Background to the research

“Organizing for Change” is a project aiming to support the fight against HIV/AIDS through a variety of actions targeted at MSM, TG, persons practicing commercial sex and people living with HIV.

Within this project, ACCEPT and ECPI have coordinated a sociological research in order to understand the health needs of people living with HIV and LGBTI people, the difficulties they face and the way in which the Romanian legislative framework responds to these challenges.

This report consists of three main sections:

Qualitative exploratory research aiming to highlight the health needs of people living with HIV, Quantitative research analyzing data obtained from an online questionnaire on a sample of 139 people, Legal research on the relevant legislation.

Objectives of the research

Investigating the current Status Quo on:

• information,

• education,

• prevention and

• access to health services by MSM, TG, sex workers and PLHIV.

Identifying the needs and challenges faced by these persons as well as the impact of these situations on the physical, mental and emotional health of the health service beneficiaries.

Investigation of the discriminatory perceptions and situations in the context of the access to the health services.

Reflection of the legislative framework in the daily lives of MSM, TG, sex workers and PLHIV.

9

Methodology of the Research

Stage 1: Qualitative research

Methodological design: 13 In-Depth Interviews with the interview duration of approximately 60 minutes and 2 Focus Groups with the discussion duration of approximately 120 minutes.

Target group investigated: included a mix of social actors relevant to the topic under investigation: PLHIV, HIV/AIDS activists, sexual and reproductive health and women’s rights activists and persons within the health system.

The data collected in the qualitative research is not statistically representative due to the small sample size. The role of the qualitative research was to explore and understand the challenges faced by persons living with HIV.

Stage 2: Quantitative research

The sample consisted of: 139 respondents (LGB/MSM people, persons living with HIV, persons practicing commercial sex, transgender persons, homeless persons).

• Nationwide distribution (respondents from 24 counties in 27 localities)

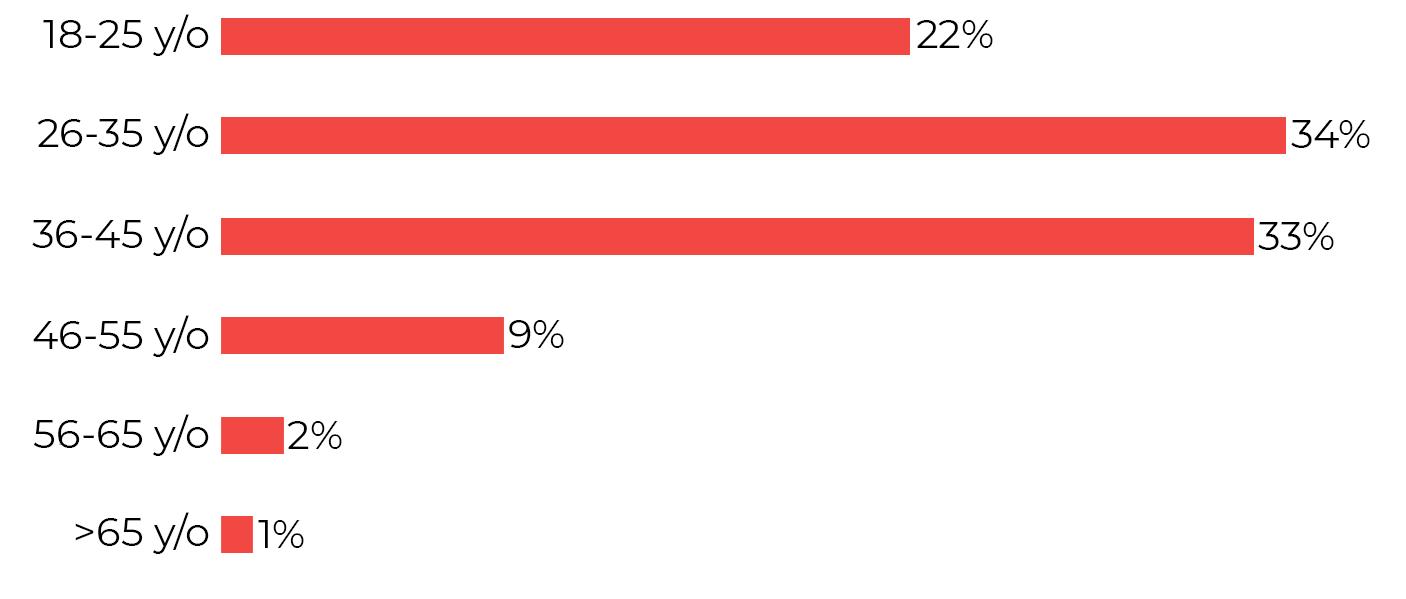

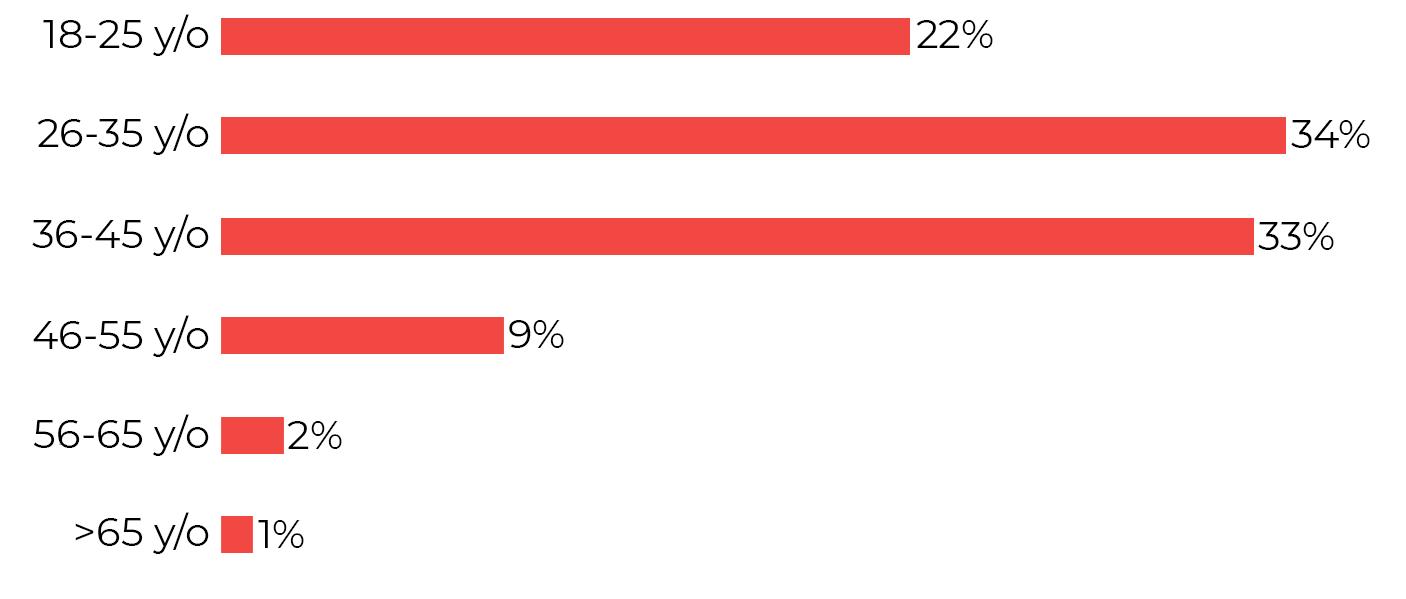

• Balanced mix by age group 18-65 (good distribution, especially in the 18-45 age range) and active-passive in employment

Sample structure in the quantitative stage

Age of the respondents How old are you?

10

Gender of the respondents

Gender

The answer to the question “Gender” was left open so that the participants could define and declare their gender identity as they wished.

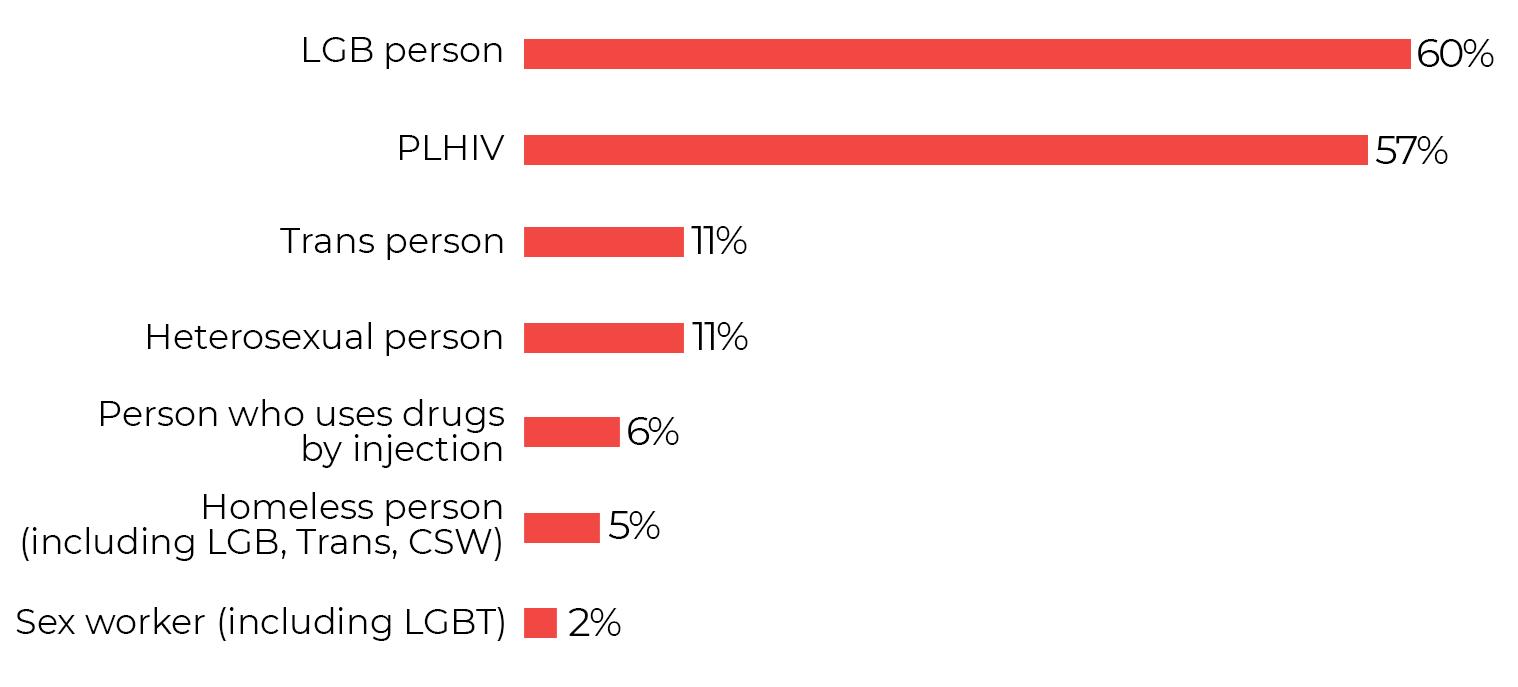

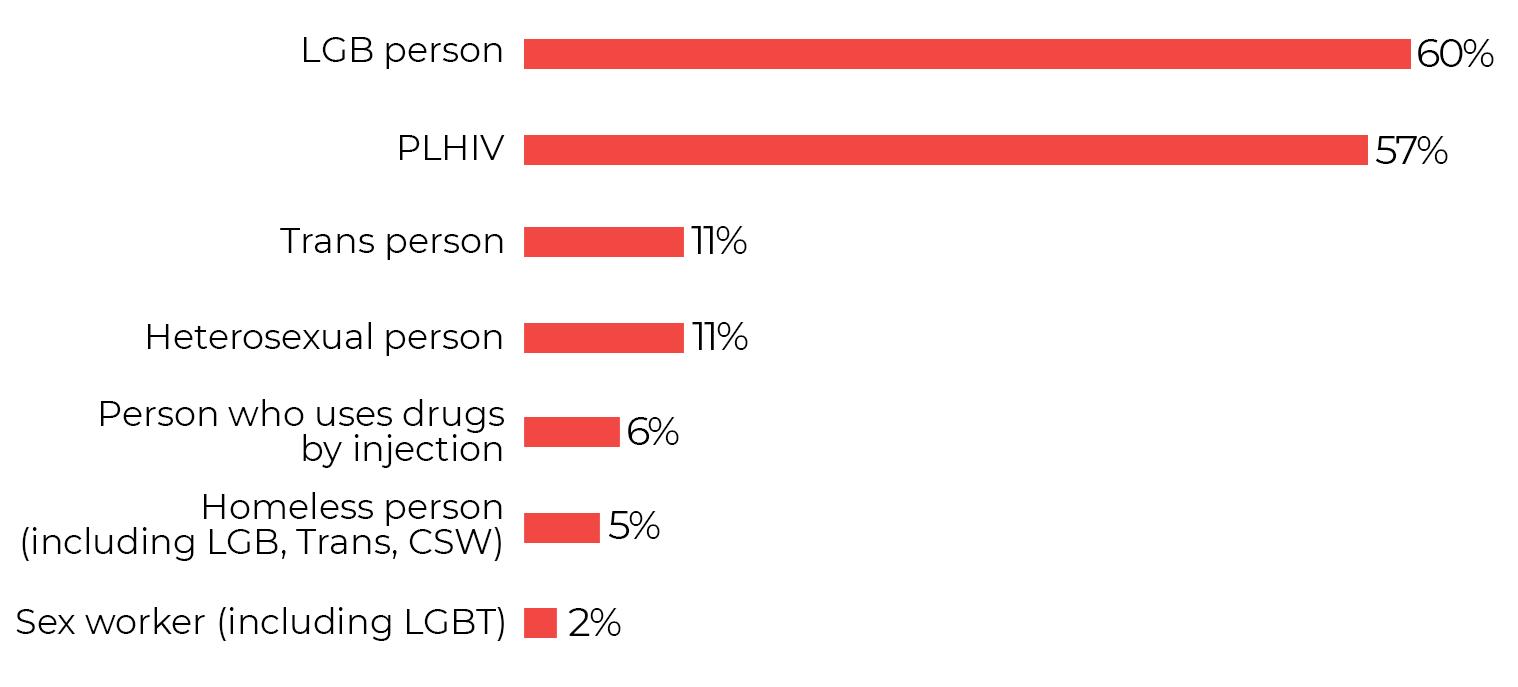

Categories of interest included in the study

Which of the following categories do you fall into?

Pre-determined sampling quota of minimum 30% HIV+ and minimum 50% LGBT in order to obtain a sample that is representative of the topic under investigation and reflective of the community of interest for this study.

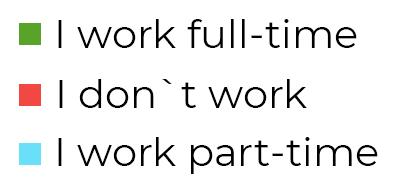

In terms of the current occupation, half (53%) of respondents work full-time, 9% work part-time, and 38% do not work.

11

Occupation

In terms of level of education, the majority of respondents (87%) have at least completed the high-school courses (primary school 8%, vocational school/ technical college 4%, high school 25%, university 35%, post-graduate studies 27%), and in terms of the time of the positive HIV diagnosis, for half of the respondents it occurred within the last 5 years.

Stage 3: Legal research

The legal research identified and structured the main legal milestones and the medical legal framework. In the analytical approach, the most relevant sources composing the HIV/AIDS normative framework were considered, such as: the HIV Law and its implementing rules, the Law on the rights of the patient and other rules in the medical system and on social protection, the Penal Code, the Ordinance on the prevention and sanctioning of all forms of discrimination.

This report presents the integrated results of the sociological and legal research.

The sociological research identifies and exposes the difficulties that persons living with HIV and those from the LGBT community face in accessing the health services in Romania.

The legal research is complementary to the sociological study and highlights the legal framework that should ensure the protection of HIV positive persons.

12

III. Sociological research

Section 1: Exploring the needs of people living with HIV in accessing the health services in Romania

The in-depth interviews conducted as part of the qualitative research revealed a positive correlation between the level of education of the study participants (PLHIV) and their own health management: the higher the level of education (university, master’s degree), the better PLHIV manage their own health. Persons with a high level of education were able to achieve an undetectable viral load due to increased adherence to the prescribed treatment. Thus, their health status is described with a focus on comorbidities (lipodystrophy, lung disease, endocrinological disease, etc.) rather than HIV.

In the case of persons with a low level of education who were more likely to be drug users and persons practicing commercial sex, the state of health was often described in terms of AIDS, with a poor management of the various manifestations of the disease. Adherence to treatment was very low, in one case non-existent.

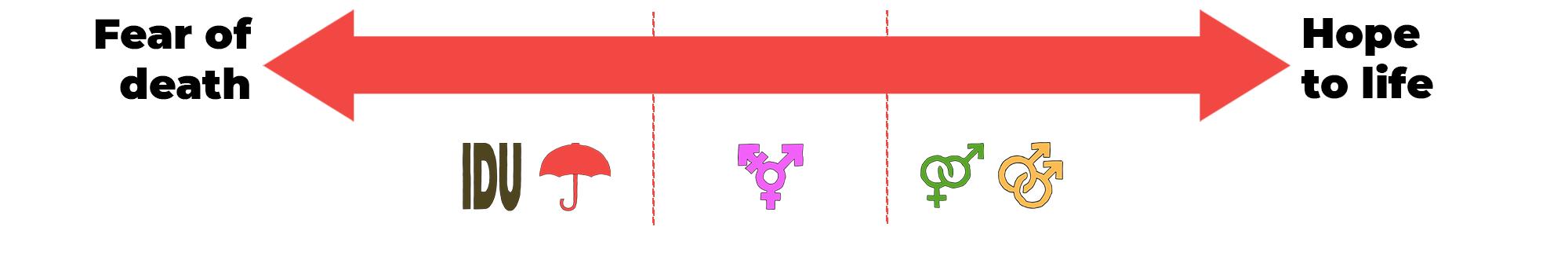

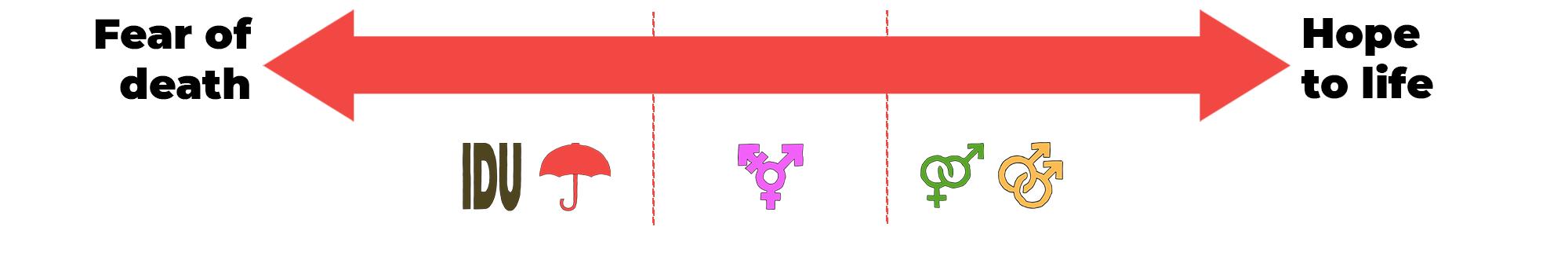

The attitude of the HIV-positive patients towards their own HIV status is generated by 2 main factors:

The drug users and the persons practicing commercial sex with low levels of education (regardless of their sexual orientation) view their HIV-positive status with a high level of negativity and resignation. The fear of death is a frequent topic in their conversations.

Low adherence to treatment is an effect of a whole vicious circle: lack of access to information makes them unaware of the importance of treatment and health professionals are reluctant to explain the long-term medical effects to these patients. Even more, these patients sometimes experience hostile behaviour from health professionals and thus end up refusing to go to hospital.

Transgender, heterosexual and highly educated gay people are rather tolerant and optimistic when it comes to being HIV+. They project a long-term future, plan for personal development and want to be actively involved in HIV and AIDS prevention and information campaigns.

14

The health professionals interviewed for the study believe that the medical progress in terms of HIV therapy has been impressive since the 1997-1998 baseline year. The treatment regimens have evolved greatly and HIV is now seen as a chronic disease that can be “compared to hypertension or diabetes”.

If I had to choose between HIV or diabetes, I would happily choose HIV. You live much more decently with HIV than with diabetes. (healthcare professional)

The medical and emotional pathway of the HIV-positive patient

The HIV-positive patient’s medical journey is accompanied by a lot of uncertainty that increases the anxiety and leads to emotional imbalances.

A state of drowsiness, muscle pain, headache, cough, fever occurs. Some patients experience very severe colds which prompt further investigations.

ELISA test (screening test) Western blot test (confirmatory test) Both tests are performed in test collection laboratories.

Following the confirmation of the Western Blot test, the patient is referred to an infectious disease physician who will take over the patient for therapeutic management and monitoring. The infectious disease physician will certify the final diagnosis

NGOs intervene at this stage and provide support.

The initiation of the treatment is performed by the infectious disease doctor. The therapeutic objective is to lower the viral load to as low as possible for long periods of time in order to restore the immune system.

After the patient has adjusted to the antiretroviral therapy and the new lifestyle, their mood improves. Adherence makes a decisive contribution to the patient’s quality of life.

Lack of treatment, especially in newly diagnosed individuals, severely impacts the balance of the HIV-positive patient and jeopardizes the previously acquired therapeutic benefit.

15

Challenges associated with HIV/AIDS

The challenges of PLHIV investigated within the qualitative research could be grouped into two main categories: direct challenges and indirect challenges generated by the presence of HIV in their lives.

Adversely affected health condition: frequent feelings of malaise, frequent chronic fatigue, nausea, muscle and joint pain, rash, fever, chills, coughing

The impact of treatment on health: multiple side effects (vomiting, drowsiness, watery stools, dental problems, etc.), the appearance of associated diseases such as candida, the therapeutic fatigue that sets in due to the fact that the treatment must be administered for life, the strictness of the treatment administration also has a strong impact on the social life of PLHIV.

Lack of treatment represents another challenge faced by PLHIV

Lack of pills is a recurring issue, HIV-positive persons face this situation every year with no explanation as to “when and how” this problem will be solved. Alternative solutions offered by the health system are:

Providing antiretroviral treatment for short periods of time: for 7-10 days; for 2 weeks; for 1 month. This alternative causes multiple lifestyle disruptions for PLHIV. They have to leave their workplace frequently to pick up their treatment. In addition, the frequent visit to the hospital brings an increased exposure of the patients and the impossibility of preserving the confidentiality of the diagnosis within the community they belong to.

Hospital visits are a source of anxiety and a constant reminder of illness for all respondents surveyed. The frequent hospital visits for treatment pick-up contribute significantly to amplifying this anxiety and to the development of a “hospital phobia” among PLHIV

16

You do realize that if I’m at the hospital every week to get my treatment, it’s almost impossible not to run into someone I know in the hallways. I most wish people didn’t know about my illness, in a small town if they do, you can say goodbye to your job, your friends... not to mention the impact it would have on my parents. (LGB HIV+ person)

Changing the therapeutic regimen with treatments that are available. Often, the therapeutic regimens recommended as substitutes are ‘outdated’ regimens containing inferior treatments in terms of the tolerability profile associated with the prescribed drug. This alternative feeds the patients’ fear of developing resistance to the therapy, thus compromising the therapeutic benefit.

Providing preferential treatment only for patients at an advanced stage of disease severity. Current protocols guiding the management of HIV-positive patients direct the health care professionals to provide immediate and nonpreferential treatment to all patients diagnosed with HIV.

I didn’t receive any treatment for the first two years after the diagnosis because my tests looked very good and the doctor said no treatment was needed. I had to have a certain CD4 and viremia value to go on treatment. Later, these protocols were changed and now the patient has to receive treatment immediately after diagnosis. (Heterosexual person, HIV+)

The emotional health adversely affected: frequent feelings of anxiety, inadequacy, depression, low self-esteem, feelings of guilt and suicidal thoughts.

Social life is severely affected: self-isolation and lack/limitation of sexual relations due to the fear of passing on the virus (especially among the less educated persons), frequent discriminatory situations leading to the rejection of HIV-positive people (avoidance and stigmatization of PLHIV, exclusion from their circle of friends, humiliation of PLHIV, difficulties in establishing long-term relationships, etc.). It is not the virus itself that is stigmatizing but the way in which the HIV+ person became infected: HIV is often associated with a depraved sexual behavior, drug abuse and a sexual orientation other than the heterosexual one.

17

I don’t understand why people are empathetic and compassionate when it comes to sick people but not when it comes to HIV+ people. You would say that we are not sick but that we should be punished for having this virus. They feel the need to blame and instigate discriminatory behaviour... as if that would make us better. (Heterosexual HIV+ person)

Exposure to potentially discriminatory situations when interacting with authorities: the medical system and the Police. Interaction with the medical system revealed situations where HIV-positive people felt humiliated and felt their right to treatment was denied. Treatment of dental problems and gynaecological conditions were listed among the most common potentially discriminatory situations.

Humiliating attitude and aggressive behaviour among the community policemen/public constables, is especially mentioned by the drug users and the commercial sex workers.

The dentist freaked out the moment I told him about my diagnosis and I saw him get all agitated around me. He started postponing my appointments and eventually told me he couldn’t see me anymore. (LGBT HIV+ person)

I think that visit to the cardiologist was the shortest consultation I’ve ever had. After I told him I was HIV positive, he immediately told me he had a lot of patients and couldn’t see me anymore. I saw him take a compress on which he had put some alcohol and touched the doorknob with that compress in his hand when he opened the door to ask me out. (HIV+ LGB person)

At the hospital they didn’t even want to give me any more pills, they said I was throwing them away so they wouldn’t give me any more. But I don’t throw them away, they paint us with the same brush and it’s not fair. And when the guards come down the street, they shout at me ”Get away from there, you AIDS-man” and they’re so scared of me you’d think I had the plague. (HIV+ drug user)

The challenges for the health professionals in managing HIV-positive patients are related to the patients’ lack of adherence to the treatment. They believe that relatively few HIV-positive patients are truly adherent (more than 90% comply with treatment) and this is due to a lack of awareness of the risks and the long-term effects of the disease.

Logistical and financial challenges that limit the public information campaigns on HIV and AIDS are also mentioned and thus a limited understanding of the disease among the general population persists.

18

At an early stage of the quantitative interview, we estimated the extent of the challenges the HIV-positive persons experience due to their current health status and how often they face them, trying to cover the challenges highlighted in the qualitative research stage:

Challenges generated by the disease stage/life with HIV (impact on overall health if you are not HIV+ but have health problems)

Challenges arising from the current treatment (side effects of the treatment)

Challenges in relation to the health system (difficulties in obtaining treatment due to the mode of distribution/absence of treatment, recurrent treatment interruptions)

Emotional challenges (psychological/emotional impact + personal life/ relationships)

Social challenges (stigmatization, discrimination, self-isolation, physical inability to take part in different activities, denial of certain health services, etc.)

The biggest challenges were found to be emotional (58%), health-related (45%) and social (45%).

Challenges

19

The data in the conclusion above represent the cumulative percentages of codes 3=Sometimes, 4=Often, 5=Very often

*Other (34 respondents). Most mentions were related to the relationship/ interactions with the physicians and the medical staff (not very LGBT friendly, lack of empathy/ disrespect of gender identity by assuming the gender at birth is same as the current gender/ fear of coming in for regular gynaecological check-up due to the sexual orientation/ older physicians and they don’t care financial challenges and finding a job or problems at the current job (absences due to ill health, fear of not being found).

A warning signal is that because of the interaction with the public health personnel, there is a risk that some patients will stop the treatment (one patient said “The physicians treat us like animals, that’s why I didn’t take treatment at all”).

Coping mechanisms in the interaction with the medical system

Coping mechanisms used by PLHIV to cope with the interaction with the medical system in Romania

Certain PLHIV prefer to avoid the interaction of any kind with the medical system in Romania even if it means depriving themselves of the antiretroviral treatment.

There are also people who, once in the halls of hospitals, try not to disturb and stay in a shadow so as not to generate an interaction with the medical personnel.

20

When I go to pick up my treatment, I don’t lift my eyes from the ground for fear that there will be an argument. The nurses are capricious... today they ask you how you are and tomorrow they pick on you because you breathe the same air as them (LGB HIV+ person)

I stopped going to the hospital because I was going in vain. The last time I went they gave me something and put me to sleep and when I woke up I was thrown out on the street...they didn’t know anything about me. I don’t need their treatment anymore because I go there and nobody pays any attention to me (Drug user and commercial sex worker, HIV+)

There have also been instances mentioned where buying small gifts (candy, coffee, flowers, etc.) and giving them to nurses/physicians manages to de-escalate the interaction between some PLHIV and some health care professionals.

Other patients, especially those with a higher level of education, make fun of trouble and adopt self-irony as a language of communication.

There are also HIV-positive patients (those with higher levels of education) who try to live with the medical system and inform themselves in advance about the degree of tolerance and acceptability of the physicians towards PLHIV and LGBT people. ARAS supports these patients with various contacts of physicians who accept to treat LGBT HIV+ persons.

I’ve made friends with the nurses at the hospital, I always buy a box of candy and tell them I’ve come to get my ”treatment” (candy) so I bring them candy. (HIV+ heterosexual person)

I don’t want to risk running into any more doctors who tell me they’re too busy so I talk directly to ARAS and ask about doctors who agree to treat HIV+ LGBT persons. That’s how I found my dentist and it’s very ok to interact with him. (HIV+ LGBT person)

Offensive attitudes are present both among HIV+ people with a high level of education and among those with a low level of education. The revolt of the patients can be found among both profiles, but it manifests itself differently.

21

People with education + : adopt an assertive attitude and do not allow medical professionals to have discriminatory behavior or show a hostile attitude. These people know their rights and are most often supported/ guided by various NGOs in claiming their right to treatment/life.

People with education – : are often conflicted and respond with verbal aggression to hostile attitudes from medical personnel. The lack of access to informative resources, the lack of education regarding the management of one’s own emotions, as well as the repeated exposure of these patients to various discriminatory situations, lead them “to the brink of despair” and make them exhibit aggressive behaviors.

I understand that they may have hard days when they see a lot of patients (and this Covid situation has further burdened their work) but that’s not my fault. When I go to the hospital, I don’t go for love but out of need and I want to get answers to my questions, I don’t accept to leave there without answers, without treatment or feeling like taken for a ride. (HIV+ LGB person)

I get angry very easily and if somebody says something to me, I’m not at all ashamed to make a fuss... I even swore at the nurses in the hospital corridor. (LGBT person, commercial sex worker, HIV+)

The physicians interviewed for this study are somewhat reserved about the mentions of the HIV-positive patients referring to their interaction with the health services in Romania. They attribute the “dissatisfaction” of the HIV-positive persons to the therapeutic fatigue and the tense situation generated by the Coronavirus pandemic.

Social activists believe that there is “no smoke without fire” and the HIV-positive patients often have to deal with medical staff who approach them from positions of power and manage to intimidate newly diagnosed patients in particular.

In terms of accessing the health services for persons living with HIV, the most common situations are:

22

Lack of treatment/interruption of treatment (delayed stock, delayed approval of funds, incorrect estimate of the treatment needed, etc.) – 65%

Breach of confidentiality (name calling in the corridor in relation to diagnosis/treatment release, waiting in shared queues with other patients with the same diagnosis) – 48%

Treatment offered for less than 30 days – 45%

The state of health not being regularly assessed (every 6 months) through specialist investigations occurs in 39% of cases, and changing treatment according to the existing stocks without a medical reason occurs in 35% of cases.

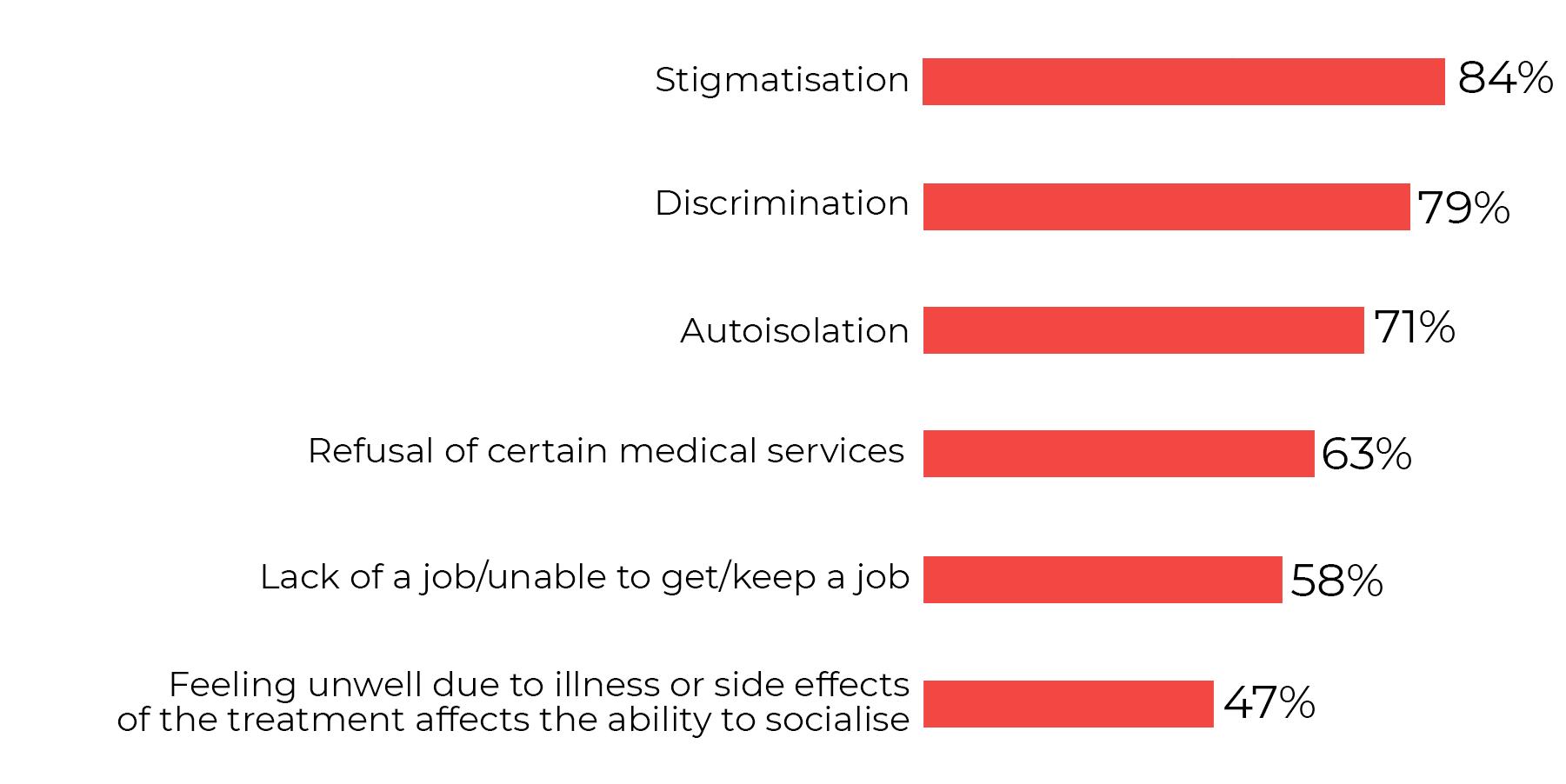

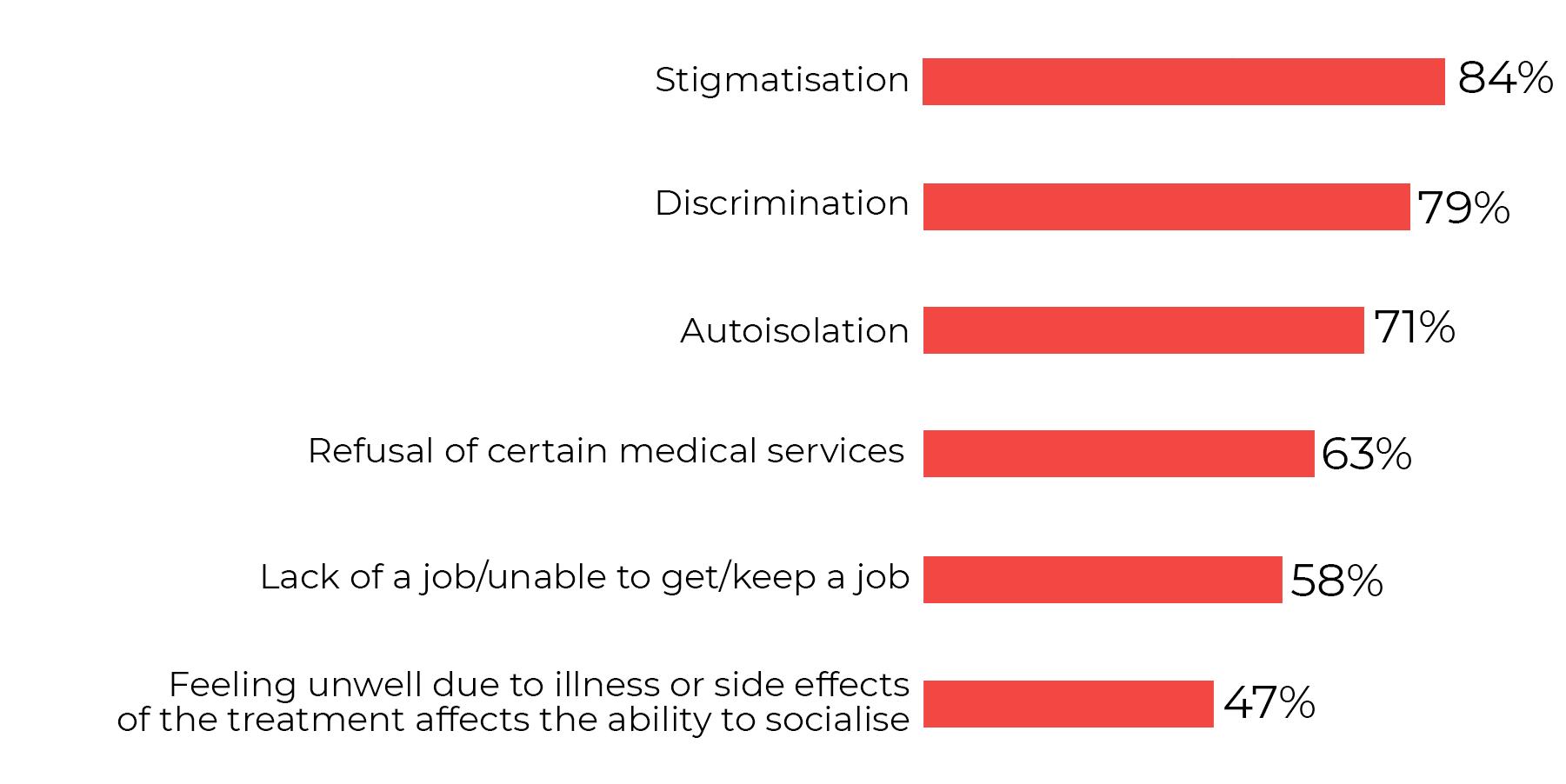

In terms of social challenges, the majority faced by the community are stigma (84%), discrimination (79%), self-isolation (71%), denial of certain medical services (63%). Also worth mentioning are challenges such as lack of a job/ inability to get/keep a job (58%) and feeling sick due to illness or the side effects of treatment affecting the ability to socialize (going out with friends, family obligations, etc.) – 47%.

Social Challenges

The data in the conclusion above are cumulative percentages codes 3=Sometimes, 4=Often, 5=Very often

When community members were asked to think about the current needs they face and their order of importance, the order in which they should be addressed,

23

the most important was the need for social acceptance, followed by (in order of importance):

Easier access to healthcare

Acceptance from those around me (family, friends, partner, etc.)

Belonging (inclusion in a group of friends)

Easier access to treatment (receiving treatment on time)

Finding/keeping a job

Access to counselling services (counselling and support through psychotherapy)

Access to financial benefits (monthly food allowance, tax relief, etc.)

Keeping my HIV status confidential

The need for acceptance and social belonging of the person living with HIV implicitly speaks to the social stigma associated with HIV and the multiple discriminatory behaviors that result from it (including in accessing the health services).

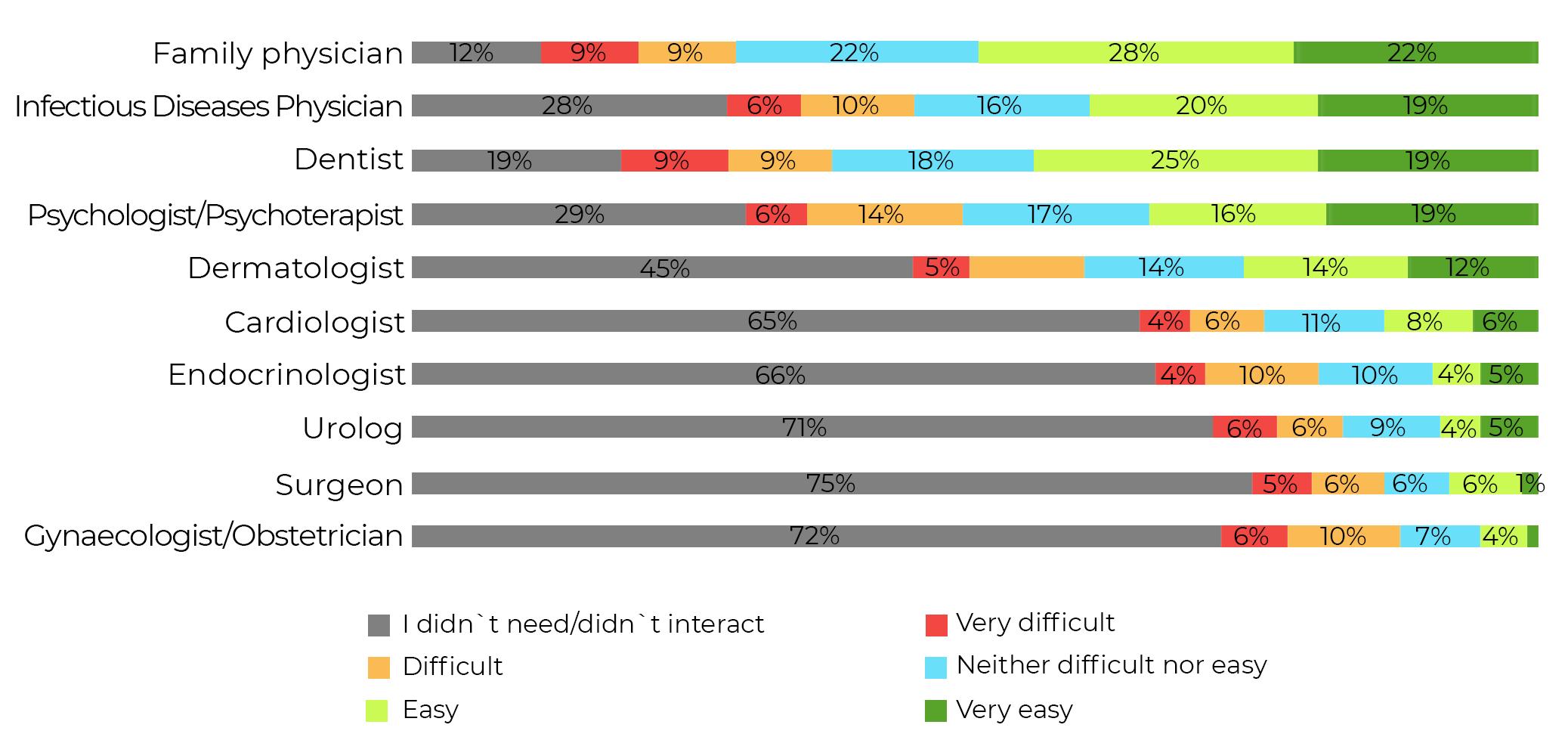

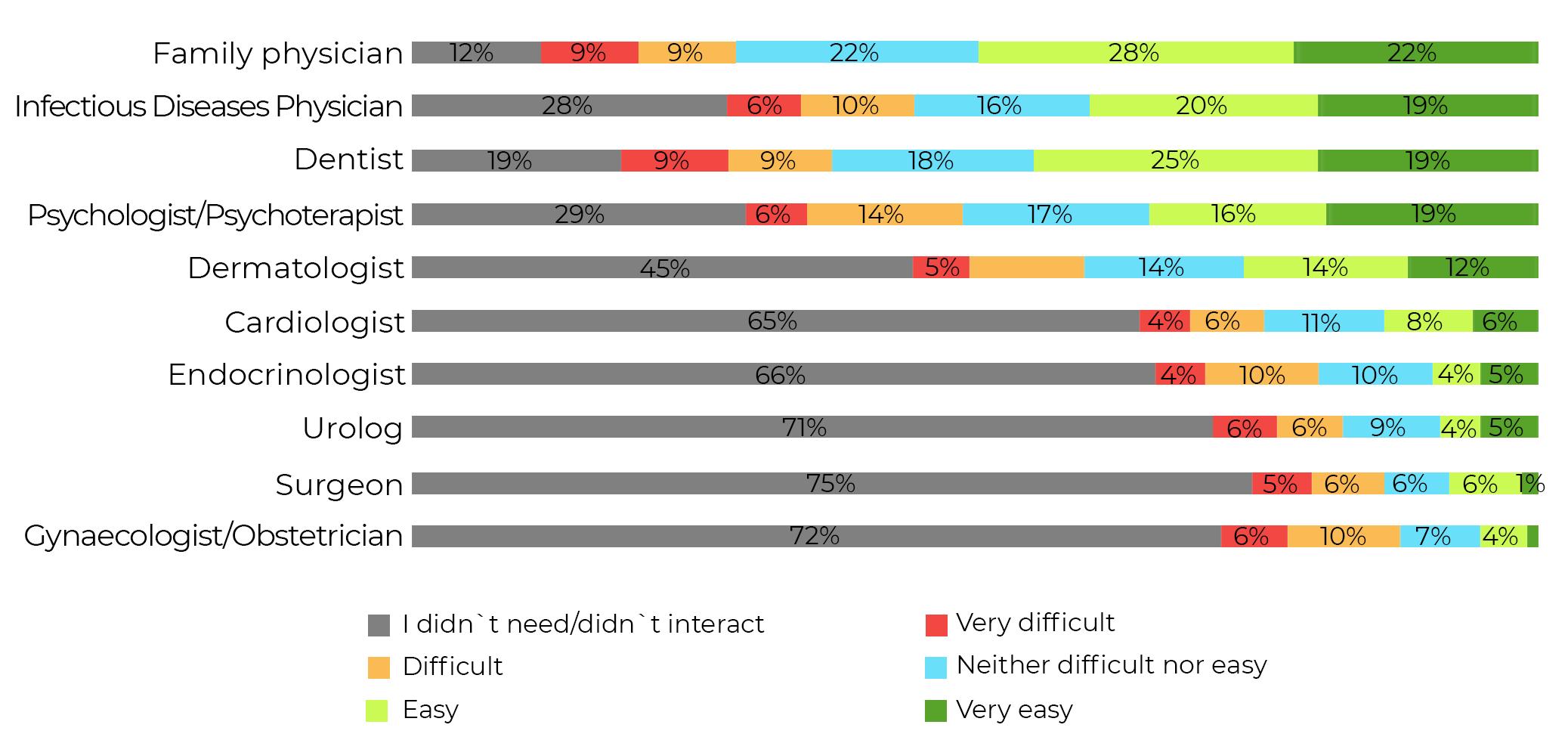

When it comes to accessing certain medical services/specialist physicians, half of the respondents have easy or very easy access to their family doctor. Other physicians accessed relatively easily are the infectious diseases physician and the dentist.

More than half of the respondents did not need or did not interact with any Cardiologist, Endocrinologist, Urologist, Surgeon or Gynaecologist

Which physicians have you interacted with so far and how easy was for you yo access that medical service?

24

According to the quantitative data, over the course of a year, the community members interacted most often with the Psychologist/Psychotherapist (on average 10 times per year, some respondents even dozens of times per year), the Family Doctor (on average 4 times per year), the Infection Doctor (3 times per year) and the Dentist (3 times per year).

Circle of trust of the person living with HIV

The qualitative research revealed that the presence of the psychotherapist is extremely important for all respondents included in the study. The positioning of the psychotherapist in the diagram of relevant people is with family members and close friends. The relationship with the psychotherapist is often described as honest, based on mutual respect and extremely helpful to PLHIV especially during the period of diagnosis and acceptance (first 6-12 months).

The relationship with the infectious disease physician is defined by the degree of professionalism of the physician (which cannot be easily assessed by the HIVpositive person) and the empathy shown towards the patient. The interaction between the HIV-positive person and the infectious physician is described as a distant relationship and contact between the patient and the physician occurs once every 6-12 months (coinciding with the time of the viremia and CD4 cell investigations).

25

An empathetic attitude on the part of the infectious disease physician and genuine interest in the patient’s problems are the two fundamental characteristics that contribute to strengthening the relationship of trust between the physician and patient.

The HIV-positive people interviewed are often anxious about interacting with the infectious disease physician; they often feel rushed, not actively listened to and unsure of the physician’s ability to recall each patient’s medical history.

I’m not sure my physician knows who I am, every time I tell him as much detail as possible so he can spot me... the problem is always time, he doesn’t have more than 5-10 minutes and things seem to be on a conveyor belt there. I would like to see that he asks me how I feel, that he actually cares about me as a person. (HIV+ LGB person)

Some HIV-positive people (especially respondents with higher levels of education) keep in touch with their infectious disease physician via text messages when needed. However, due to the pandemic context and the restrictions imposed by the authorities, some patients have not interacted with their infectious disease physician in the last 1.5 to 2 years.

In the last two years, many infectious disease physicians have been giving priority to coronavirus-infected patients and there has been a transfer of HIV-positive patients only to certain infectious disease physicians. This setup is a source of dissatisfaction both for the patients who feel “abandoned” and for the health professionals who feel they no longer have control over the therapeutic progress of their HIV patients.

Now, because of the pandemic, we have had to do some re-organisation, the vast majority of physicians are only dealing with Covid patients and we have kept only a small core of physicians dealing with the HIV patients. This nucleus consists of about 6 physicians who have to see 1500 HIV patients every month... and I no longer have direct contact with my HIV patients who I used to see every 1-3 months. (medical professional)

26

The role of NGOs

The role of the NGOs is also extremely important in the relationship dynamics of the HIV-positive person. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the work of the NGOs has been hampered by the large number of requests received from PLHIV.

Access to the hospital was restricted and many of the questions from the HIVpositive patients were addressed directly to the relevant NGOs.

NGOs are invested with a lot of trust (both by the patients and the health professionals) when it comes to accurate, complete and always updated with relevant HIV information in the medical and social sphere

Preparing the necessary documentation to access various social benefits is another support activity offered by the NGOs in support of the HIV-positive persons

The role of emotional support, advocacy and membership of the relevant groups for the HIV-positive persons is also associated with non-governmental organisations.

The NGOs are seen as a binder between PLHIV and health professionals, often accompanying the HIV-positive patients when they first interact with health professionals

The quantitative research shows that for half of the respondents (54%) living with HIV is more of a disadvantage in accessing the health services, and 32% cannot judge whether it is a disadvantage or an advantage.

Similarly, for half of the respondents (53%), being part of the LGB/ MSM community is more of a disadvantage in accessing the health services, and 43% cannot judge whether it is in their favour or not when accessing the health services.

27

And for the majority of those from the Trans community (93%), their status is more of a disadvantage when they need to access a medical service.

Health services in Romania

On a scale of 1 to 10, the average level of satisfaction with the quality of the health services in Romania is 4.8, and the average level of trust in these services is 4.7, with the Trans persons and the persons practicing commercial sex giving the lowest scores (averages of approx. 3 and 2 respectively), the highest scores being given by drug users and homeless people (averages of 7 for quality of services and 6 for trust in these services).

The quality of care is described in terms of access to modern treatments with fewer side effects, easier administration (one pill a day) and less impact on the lifestyle of the HIV-positive persons.

PLHIV who took part in the current study believe that state-of-the-art treatments are now available in Romania. However, access to these treatments is sometimes considered to be preferential offered by the physicians especially in small towns or rural areas

I know that there are treatments with fewer side effects and that they are administered in one pill a day but my physician didn’t want to prescribe me this therapeutic scheme. ARAS encouraged me to ask for a newer (therapeutic) regimen, but the physician said he knew better. I kept hearing about the different gifts and attentions you have to give if you want to have access to better treatments. (LGB person, HIV+)

I know for sure that there are state-of-the-art treatments in Romania, but due to certain political and economic interests, some patients are still kept on outdated therapeutic schemes. I encourage everyone I talk to go and ask their physicians to reevaluate the need to change the treatment... especially when they are experiencing serious side effects. (social activist)

When it comes to personal experience with public health services, the intention to recommend the public health services in Romania to a friend is very low (average of 4.1).

28

Satisfaction scale: 1=Very dissatisfied, 10=Very satisfied

Confidence scale: 1=Not at all confident, 10=Very confident

Recommendation scale: 1=I would definitely not recommend, 10=I would definitely recommend

29

Section 2:

Contextualising the lack of antiretroviral treatment.

In terms of receiving treatment/prescription refills, this type of service is accessed on average 8 times per year, and the health monitoring tests take place on average 2 times per year (for 44 of the respondents, the tests were performed only 1 time per year, and for 15 persons, not at all).

In general, tests to monitor treatment are carried out at the request of the patient in 62% of cases or on the recommendation of the specialist/infectious disease specialist in 56% of cases.

Satisfaction with the current antiretroviral treatment is good (average 8.2, with half of the respondents giving a score of 10).

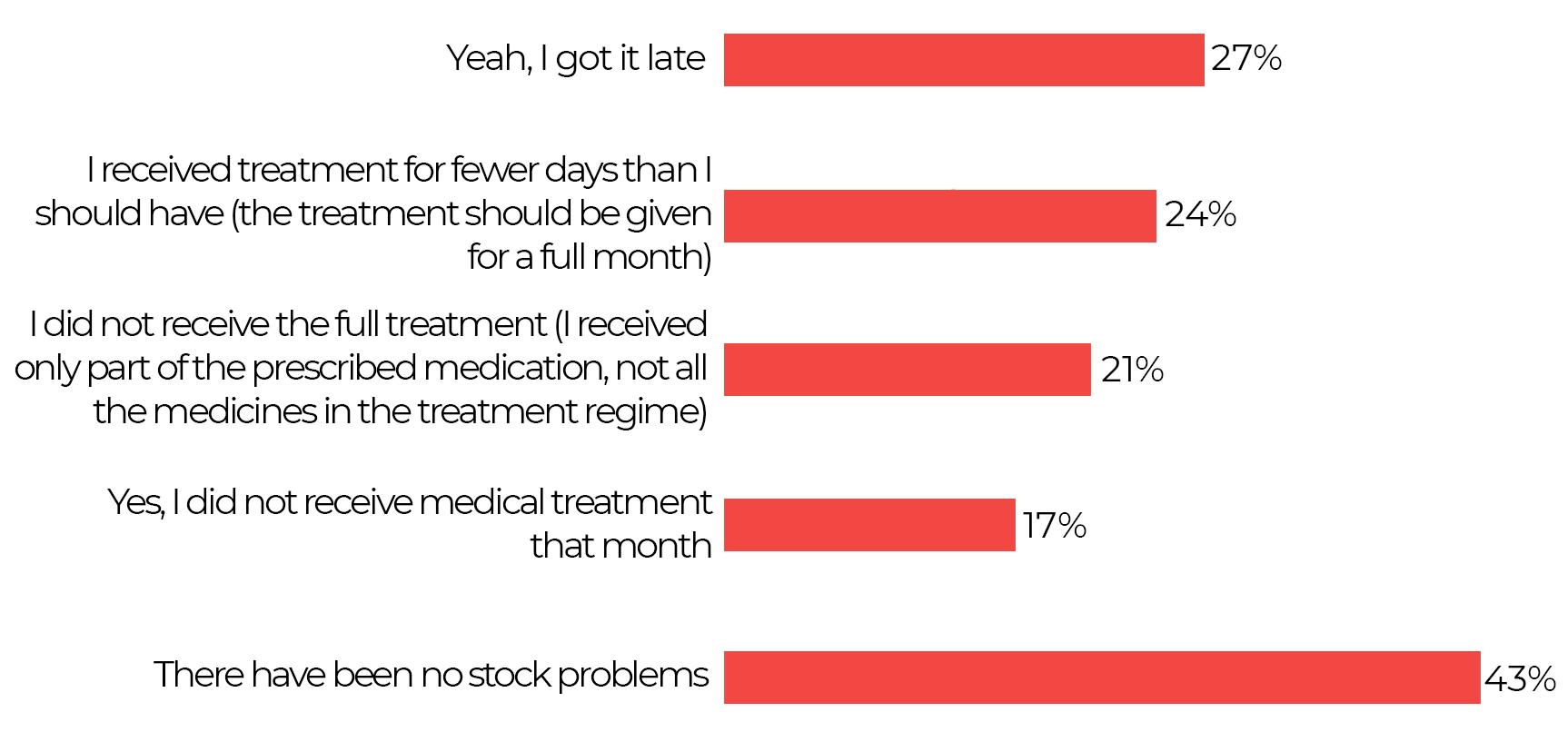

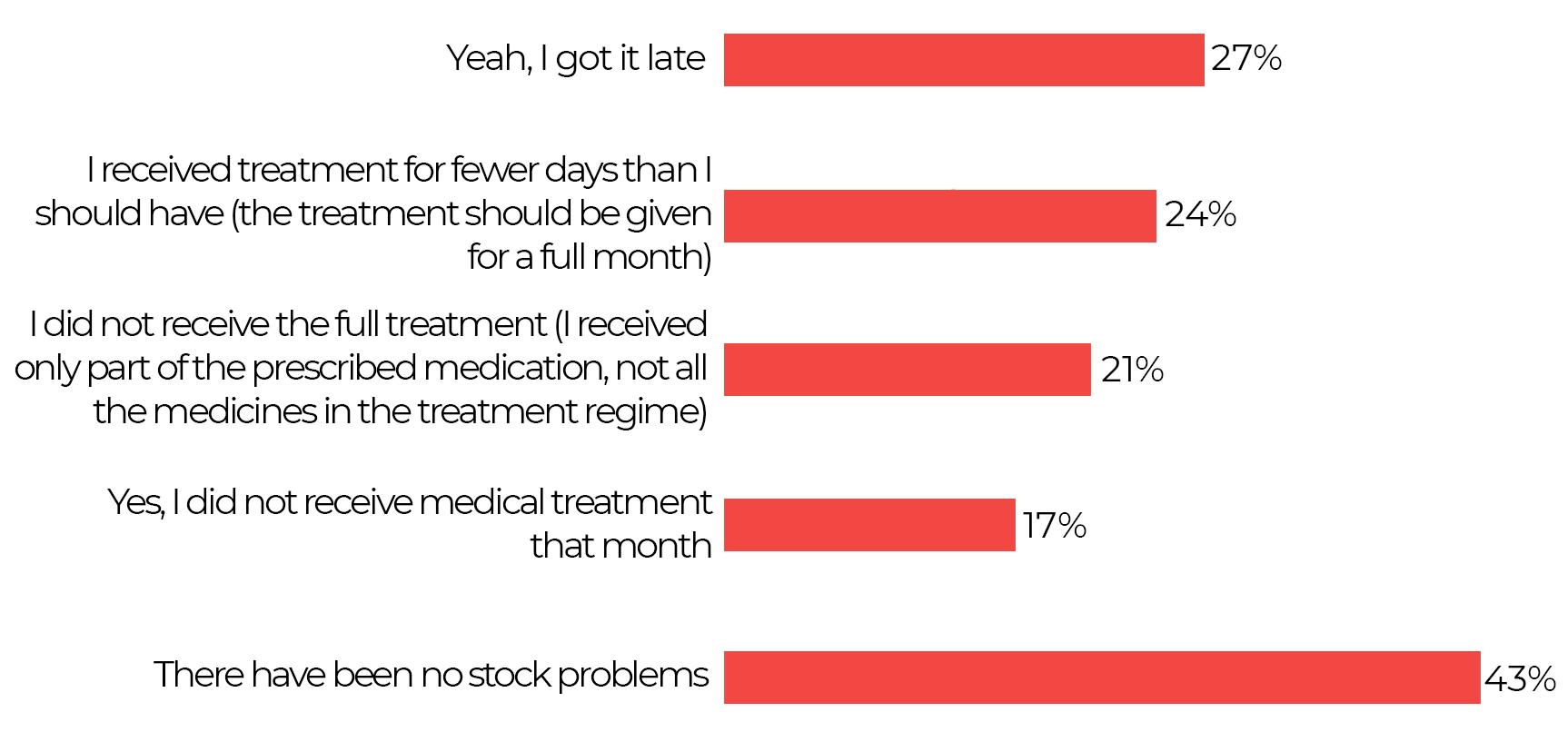

When asked if there were situations where treatment was not available, more than half of the respondents (57%) encountered problems: they received it late or for fewer days than they should have (treatment was supposed to be offered for a whole month) or they even did not receive the full treatment (they received only part of the prescribed medication, not all the drugs in the treatment schedule). In these situations, the patients have to create/build up a stockpile. 43% of respondents had no stock problems.

Availability of the treatment

30

In the pre-COVID period the patients were told on average twice a year that one or more of their medicines were missing, and in the COVID period these situations doubled in number (on average 4 times a year). n).

Coping with the lack of treatment has generated anxiety and fear among the HIV-positive persons (especially among newly diagnosed patients in the last 1-2 years) and there are various ways in which these patients try to acquire a reserve stock in order to avoid such future stresses: go to pick up their monthly treatment 2-3 days earlier and thus manage to save a few pills each month they try to buy a refill bottle from other countries but the cost is prohibitive for most of the respondents surveyed they try to borrow or buy from other HIV-positive persons if the treatment regimens are similar in desperate situations, they turn to Alina Dumitriu (Sens Pozitiv) for help in getting the treatment

Interviewees from the health system see the gaps in the provision of antiretroviral treatment as a consequence of the turmoil created by the Coronavirus pandemic. Basically, the whole medical system focused on treating Covid patients and they had priority over the chronically ill. The strategy of the medical system was decoded as one of ‘survival’ being highly reactive to the large number of Covid cases.

Since Covid-19, all we’ve done is survive and we’ve focused less on the quality of survival. We hope to get back to better times. (healthcare professional)

The representatives of the non-governmental organizations which were involved in this study are of the opinion that this “pill crisis” is not only rooted in a mismanagement of the logistical implications generated by the pandemic context, but is linked to an underbudgeting of the national HIV plan in the context of the non-existence of the National Strategy for Surveillance, Control and Prevention of HIV/ AIDS. The recurrence of the “pill crisis” occurs year after year and is not an isolated event generated by Covid-19, but accentuated during the

31

pandemic. Every year, the signing of the budget amendment is usually delayed and thus the whole logistical circuit suffers, and the stocks of treatment needed by the HIV-positive people are significantly reduced.

There is also the perception that the more social actors are involved in the decision making, the more diluted the responsibility will be and the final decision will be repeatedly delayed.

It’s no use that it falls under the responsibility of the Minister of Health because it has no power if it has no money to allocate to these treatments. Antiretroviral treatment is free for all HIV-positive patients and yet there are long periods when they do not have access to the treatment. The responsibility for providing this treatment should be in the hands of those who have the power of financial decision, those who sign the initial budgets and their amendments. (social activist)

The quality of life at this moment for the HIV-positive patients, with the current treatment, taking into account the services provided by the Romanian public health system, was evaluated at an average level (average of 6.4, on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1=very bad, 10=very good). The persons who practice commercial sex tend to have a significantly lower quality of life.

32

3: Understanding discrimination,

The main sources of information used to stay informed about HIV or other diagnosis (prevention, disease, health status) are the Internet/search engines (Google, etc.), NGOs, the Internet – specialized websites and the specialist (the specialist being a source used significantly more by the heterosexual persons).

Information sources - HIV/other diagnostics

Regarding the sources of information used to stay up to date with the information about the treatment and the health services, the preferred ones are the Internet, the specialist physician and the family doctor (especially the LGB persons tend to access the various sources more, compared to Trans persons, sex workers, drug users).

Specialized Internet sites, NGOs and Social Media are sources of information used to a significantly greater extent by Sex Workers to keep up to date with information related to HIV or other diagnosis. The Psychologist/Psychotherapist

33

Section

prevention, information and the interest of the persons living with HIV in the context of the legal framework in Romania

and the persons with the same diagnosis are sources of information that are significantly more used by the persons aged 18-25 when they need information about treatment and medical services.

The fact that the Internet is the main source of information accessed shows the need for effective national information campaigns to encourage people to access official sources, and at the same time to understand which sources are relevant in order to access accurate, up-to-date and useful information. The fact that the NGOs are at the top of the list of preferred sources could facilitate a close collaboration between the NGOs, the state and the health professionals.

Discrimination

1 Intersectionality = “analytical tool for studying, understanding, and addressing the ways in which sex and gender intersect with other personal characteristics/identities and how these intersections contribute to unique experiences of discrimination.” (https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/ default/files/a_union_of_equality_eu_action_plan_against_racism_2020_-2025_ro.pdf )

34

The anxiety regarding the access to health services by PLHIV is strongly rooted in the “Intersectionality” 1 of different social identities that can generate discriminatory behaviors among the health professionals. The lower

Surse de informare - tratament și servicii

the educational level of the HIV positive persons investigated and the more overlapping social identities (sexual orientation, ethnicity, socio-economic status, etc.), the more they will experience fear of the interaction with the health professionals.

There is a preconception that the attitude of the health professionals is rather distant, authoritarian and lacking empathy towards the patients in hospitals. When a highly socially stigmatising pathology (HIV+) and a sexual orientation other than the heterosexual one also plays a role, the risk of discrimination and aggressive behaviour (verbal, emotional) increases significantly.

...he/she shouted after me ”Mister” like it was the first time he/she had seen me and I was dressed just like I am now, in girl clothes and I have long hair and I was wearing make-up. They just don’t want to respect that I feel like a woman and they always talk dirty and I get reprimanded when I go for my treatment. (LGBT person, sex worker, HIV+)

I went to the hospital in my home town with a friend who had been bitten by a bee and was feeling sick and we went to the emergency room and when the nurse came in, he told her he was HIV positive and she shouted across the corridor to another nurse ”Be careful, he’s an AIDS-person, don’t touch him... you can tell from far away that he has AIDS”. (LGB person, HIV+)

When discussing the legal framework which assesses/manages cases of discrimination, 6 out of 10 respondents are aware of this type of information, but only 12% of respondents have also taken such steps when they/ someone else in the community has been discriminated against.

Do you know information about the legal framework that assesses/deals with cases of discrimination?

35

For cases of discrimination of any kind (gender, race, etc.), people in the community prefer to turn to anti-discrimination NGOs in 54% of cases, or to the CNCD = National Council for Combating Discrimination in 42% of cases.

Although they know which authorities can help them report a discriminatory behaviour, most HIV-positive persons prefer not to do so for fear of exposure. Most often they seek help from the NGOs and ask them for legal support to solve their problems, without agreeing to come forward and file a formal complaint.

The vast majority of respondents, almost 80%, believe that the incrimination2 of HIV transmission makes access to HIV testing/treatment services more difficult/ influential.

Exposure of HIV-positive status

There are three factors that determine the exposure of HIV-positive status especially when accessing health services. Most respondents interviewed declare their HIV+ status out of concern for their own health status as well as the health status of others.

2. Article 354 of the Criminal Code: “(1) The transmission, by any means, of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome – AIDS – by a person who knows that he/she suffers from this disease shall be punished by imprisonment from 3 to 10 years.”

36

Who do you turn to in cases of discrimination of any kind (gender, race etc.)?

Legal framework: Few people living with HIV see the legal framework as the main motivating factor for declaring their HIV+ status. Some respondents consider it a legal obligation to declare their HIV-positive status though, others consider it <slightly abusive> because their confidentiality is violated and once declared, they risk hostile attitudes.

Care for others: even though there are well-established protocols for the protection of health professionals (wearing masks, surgical gloves, etc.), certain HIV-positive persons feel the need to draw the attention of the health professionals so that they can protect themselves properly.

In couple relationships, even when the HIV-positive person is undetectable (i.e. the virus is not transmissible), they still feel the need to share this information with their partner as a sign of respect and care for their relationship.

Caring for oneself: the declaration of HIV-positive status is often initiated by patients in order to ensure that the physician will take this diagnosis into account when conducting clinical investigations and recommending treatment. There are multiple drug interactions that HIV-positive patients fear could have a negative impact on their health. Most are of the opinion that this exposure of the HIV+ diagnosis brings the risk of hostile/discriminatory behaviors but prefer to choose the <most manageable evil>.

The medical professionals investigated are of the opinion that this diagnostic confidentiality is not violated because there are now well-established protocols by which the physician can have access to the patient’s medical history in order to treat him/her: during the consultation, the physician will ask the patient what other treatments he/she is currently taking and, depending on his/her answer, he/she will know exactly which treatment to prescribe in order to avoid drug interactions that may be harmful to the patient.

We have very clear protocols that guide us to ask the patient what other treatments they are currently undergoing. Depending on the patient’s answer, we will also find out about the HIV+ diagnosis immediately without forcing the patient to reveal this to us. In this way, we will be able to immediately recommend a treatment that does not interfere with the patient’s current treatment”. (healthcare professional)

Social activists believe that there is a clear protocol regarding the protection of healthcare professionals when interacting with their patients: physicians, nurses and any healthcare professional must take

37

all protective measures as if the patient in front of them might have an infectious disease. Some of those interviewed believe that HIV-positive patients should not be asked if they are HIV+ in order to avoid exposure to potential discriminatory behaviour.

The physician must behave as if all their patients are possible carriers of HIV, hepatitis, etc. They must wear gloves, a mask and have a whole protocol which if they follow, they will be perfectly safe. I don’t understand why the patient has to declare whether they have HIV or not... this is a violation of the confidentiality of the diagnosis and then the patient risks hostile or aggressive behaviour. (social activist)

HIV Prevention

Both PLHIV interviewed and the social activists involved in this study are of the opinion that ”HIV prevention” in Romania is an almost non-existent topic and this initiative is rather left to the NGOs.

In the context in which Romania has been lacking for several years a national strategy for the surveillance, control and prevention of HIV/AIDS cases to be approved by the Government, the subject of prevention is not widely addressed.

Health professionals support initiatives that address HIV prevention in Romania but believe that these initiatives should be coordinated at ministerial/government level so that there is alignment and consistency in the information provided to the general public.

They believe that prevention can only be achieved through integrated public information and education campaigns on HIV and AIDS.

NGO efforts in this direction are conditional on the availability of their own resources. There is very little testing capacity among hospitals and the testing services provided by NGOs are insufficient.

The Semper Musica Association is mentioned as an example of ”good practice” because it has managed to implement various actions in high schools to discuss the topic of HIV and methods of prevention in the spread of this virus.

8 out of 10 respondents have heard about PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis to HIV infection), the vast majority (97%) consider that the introduction of PrEP in

38

Romania is important, and almost unanimously (99%) the community members who were included in the survey consider that it is important that this protocol is communicated and explained within the community (for 92% of them it is even very important, and especially for HIV positive and LGB persons).

PrEP involves the use of an HIV/antiretroviral drug by an HIV-negative person to prevent HIV infection. The anti-HIV drugs in PrEP stop the replication of the virus in case of sexual contact with an HIV-positive person. Access to PrEP and information about this prophylactic measure can positively impact the intimate and social lives of the persons living with HIV.

Moreover, 94% of respondents say that it would be useful to organise a national campaign to promote this protocol.

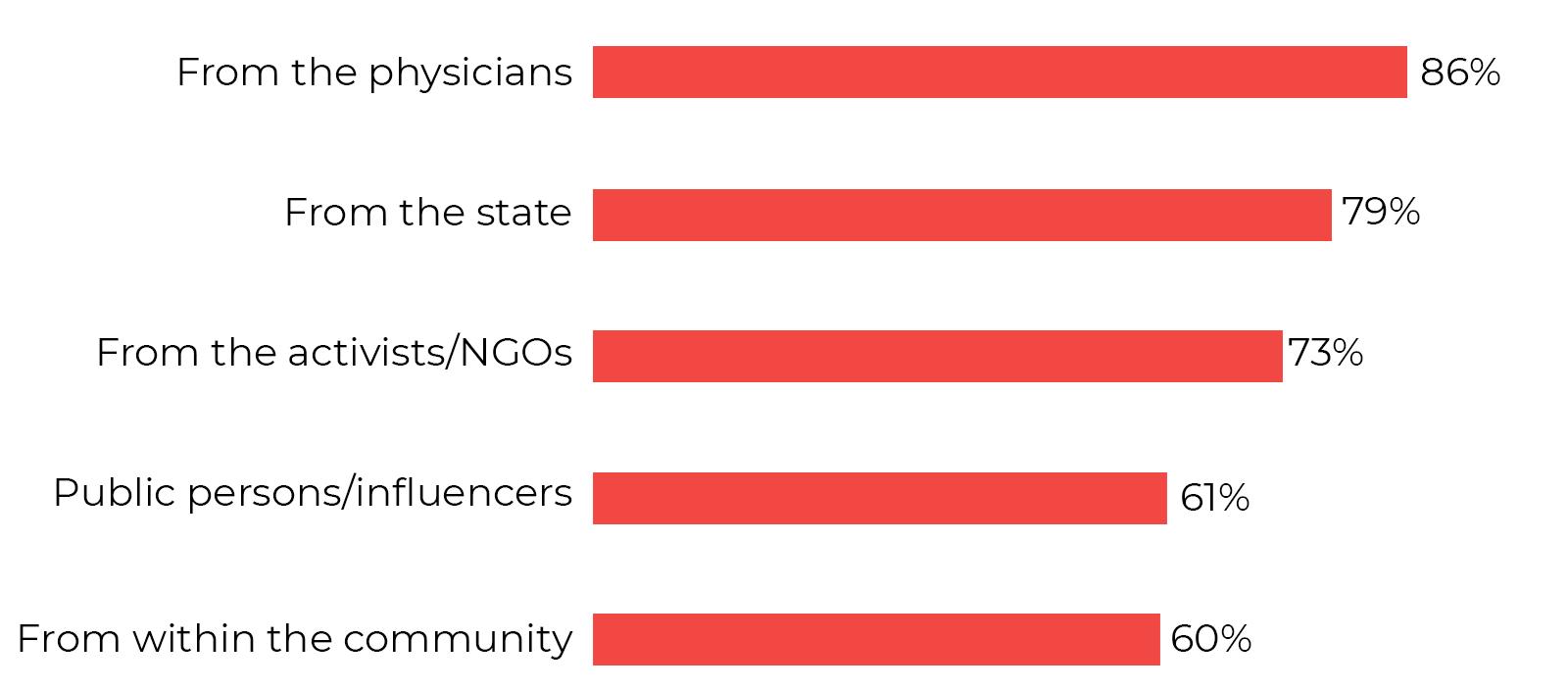

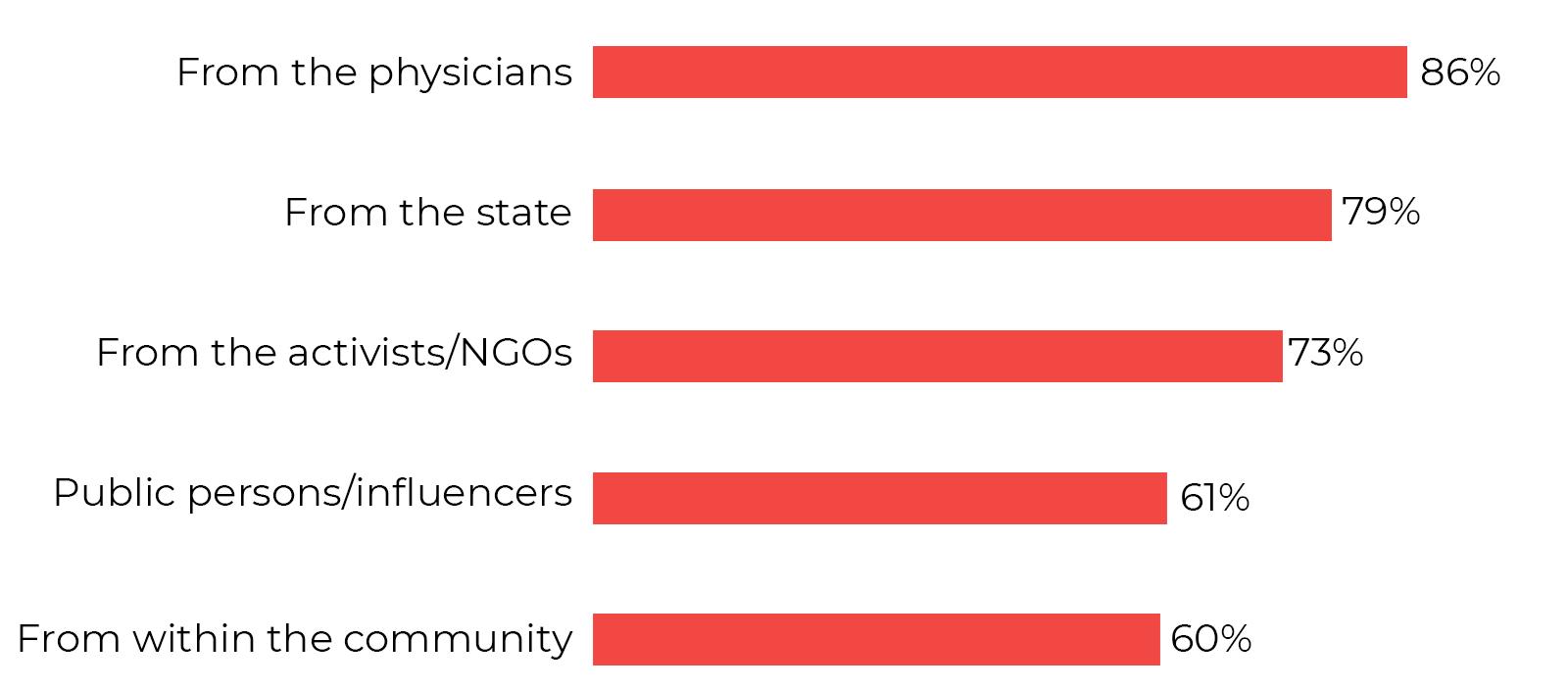

The respondents believe that this information about PrEP should come mainly from physicians and the state, and that the activists/NGOs would come third in this ranking.

From whom should information about PrEP come

In the Top 3 biggest problems faced by the Romanians, the respondents included access to health care, access to education and access to equality, without any restriction of status, race, gender, etc. (non-discriminatory access to work, access to public and private services, etc.). Access to legal advice (particularly important for LGB persons and those aged 18-25) and access to free expression follow in the ranking. Access to equality is particularly important for PLHIV and persons who use drugs

39

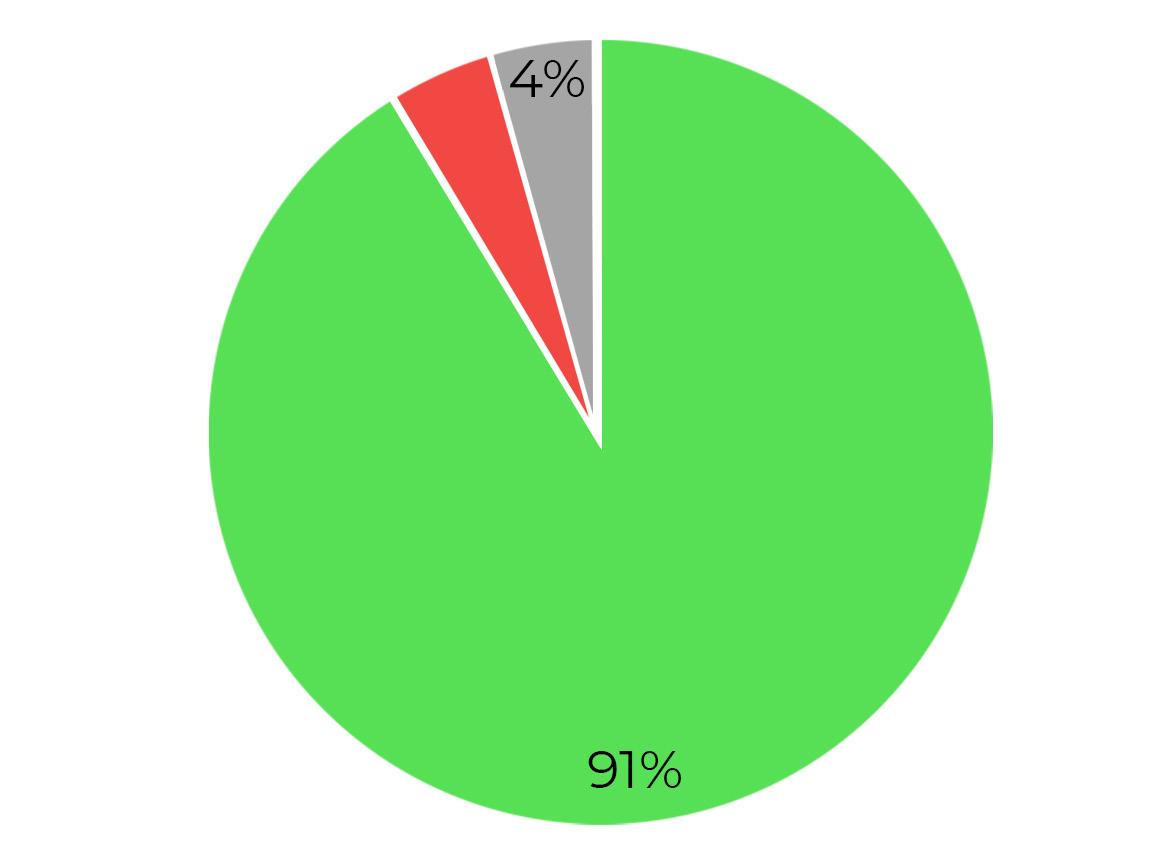

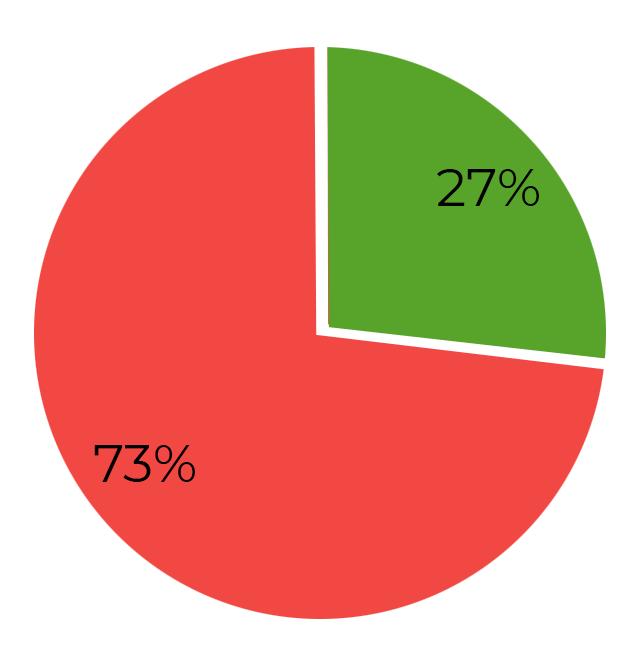

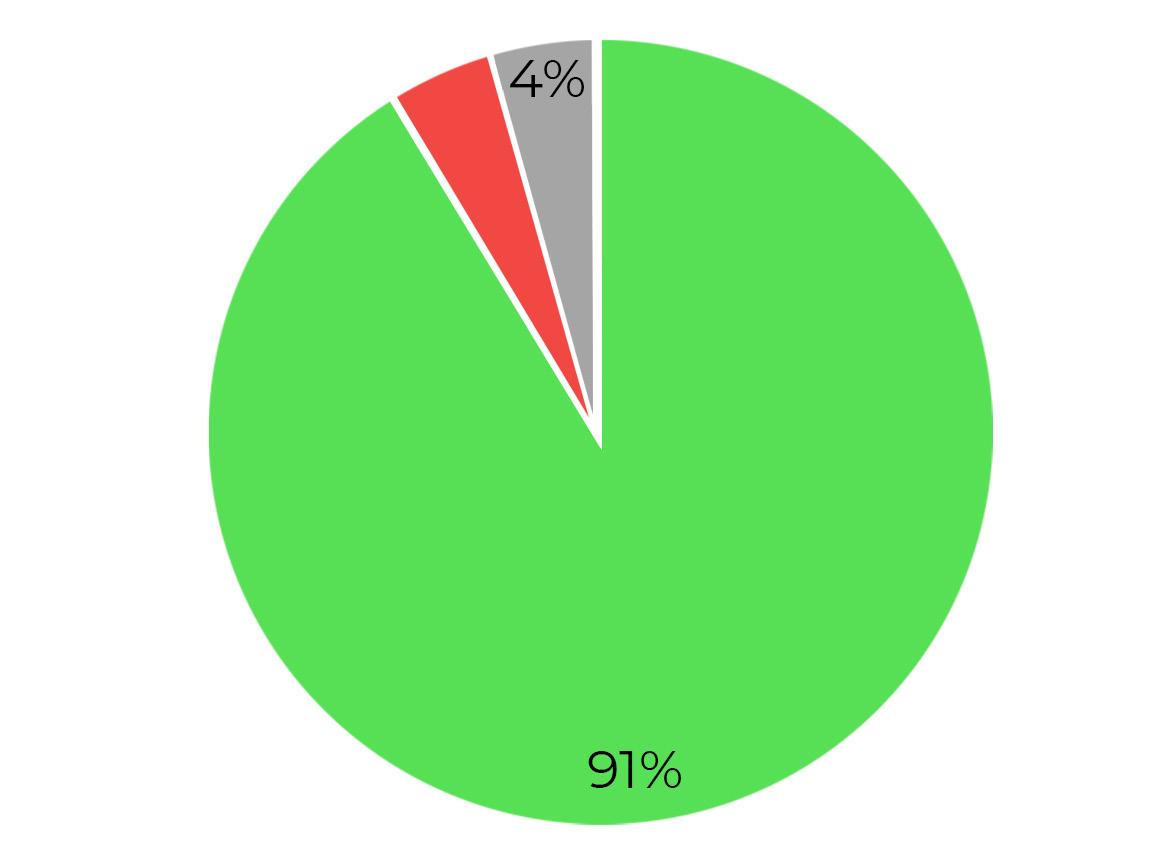

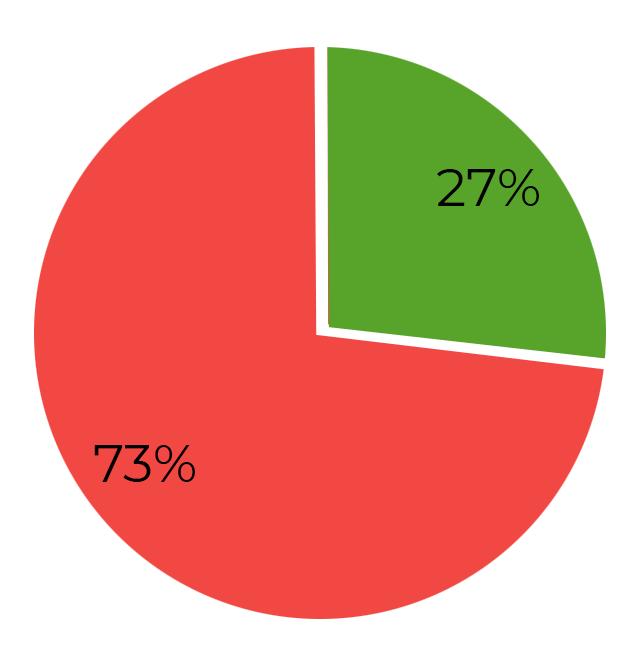

Regarding sex education/health education in schools, 73% of the respondents did not have access to this type of education in school.

Have you had access to sex education/health education in school?

91% of the respondents believe that sex education/health education definitely contributes to a healthier population.

Do you think that the access to sex education/health education is necessary/ contributes to a better health of the population?

40

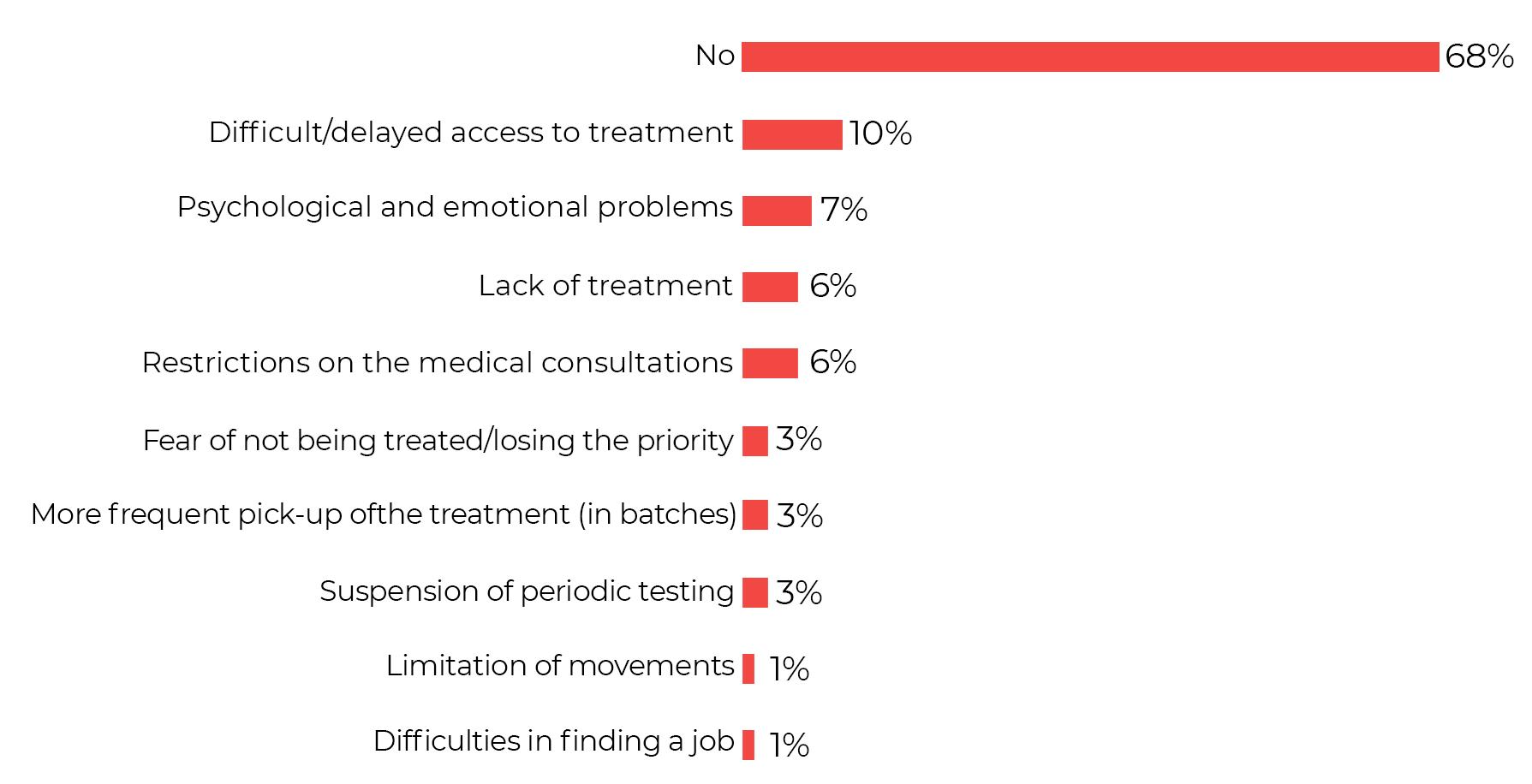

Impact of Covid-19

The impact of the COVID pandemic was felt mainly through restricted access to the health services (hospital, doctor, tests), the medical system was blocked and the lack of organisation was felt. Patients were also affected by the hampered/ delayed access to treatment. Some patients lacked proper communication with health professionals, some feared the way in which COVID could impact HIVpositive persons, they needed psychotherapy more often, chronic diseases were sometimes neglected by the specialists, exacerbations occurred following the COVID infection.

An interesting response was the opinion of one patient: “It seemed to me that the GP didn’t consult as often anymore, but just gave referral notes.”

Psychologically, PLHIV lived with the fear of getting sick, anxiety, a sense of unpredictability, putting off everything that could be put off.

Certain patients felt a positive impact, through the respect for confidentiality (e.g., no more shouting of names in the corridor) or by receiving treatment for 3 months and having an easier access to doctors through online consultations.

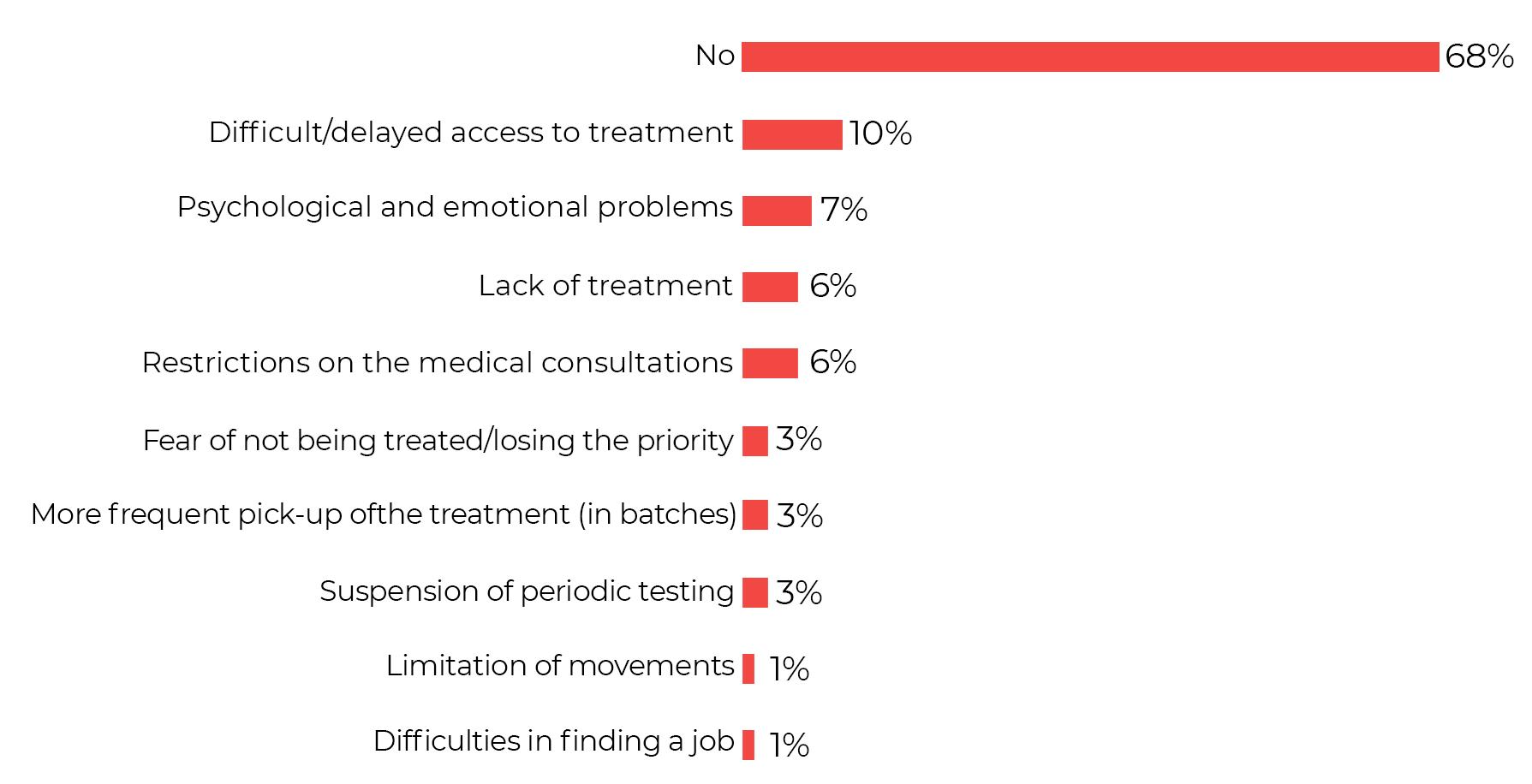

What impact/implication have you experienced as a result of the COVID pandemic in terms of access to healthcare?

41

Other implications experienced as a result of the COVID pandemic, related to HIV patient status, were:

Psychological and emotional problems (fear, insecurity, social marginalization)

Lack of treatment (“Lack of specific drugs was motivated by the diversion of funds to fight COVID”)

Restriction of medical consultations (difficult access especially to specialist physicians)

Fear of not being treated/no longer having priority (“initially the anticovid vaccine eligibility database does not communicate the HIV patient eligibility”)

Were there any other implications, felt in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic, related to your status as an HIV patient?

42

Section 4: Conclusions of the sociological research

The main fear and difficulty of PLHIV resides in the social stigma (84%) that feeds the discriminatory behavior (79%) among the general population and specifically even among the health professionals.

Discrimination arises as an effect of the intersectionality of different social identities and HIV-positive status: HIV/AIDS has a strong social stigma associated with it, on top of which overlaps the sexual identity, socio-professional status, ethnicity, etc. The more overlapping social identities there are, the greater the risk of discriminatory behavior.

Although aware of the existence of certain rules and laws aimed at protecting people living with HIV, PLHIV prefer not to seek help from the authorities because they fear public exposure. They often turn to the NGOs (54%) for help and guidance

The respondents surveyed believe that there are inconsistencies in the way these laws are implemented in practice and there is no effective control procedure to redress the discriminatory and illegal behavior.

Life with HIV is an overwhelming emotional rollercoaster and the difficulty in managing it does not come from the medical challenges associated with HIV, but rather, from the social and emotional ones: rejection, lack of belonging, feelings of loneliness, anxiety, depression, guilt projected by others onto persons living with HIV and internalized by them, etc.

The HIV-positive person’s circle of trust is limited and the specialist physician is often not invested with a priority support role. Family, friends, NGOs and the psychotherapist are part of the emotional support team accompanying the HIV+ patient’s journey.

The involvement of the NGOs in the dynamics of the relationship between HIVpositive patients and the health system is very important because the social activists are invested with the role of ”Patient Navigator”3 .

3.The navigator is the person who helps the patients to understand and accept their illness, explains the therapeutic pathway, helps them with their medical file, accompanies them to medical check-ups and explains the results of the medical investigations; tries to motivate the patient by presenting success stories and offering emotional support.

43

There are discrepancies between the experiences of PLHIV and the statements of health professionals when discussing the lack of treatment:

he HIV-positive patients notice a recurrence of the lack of treatment and often become anxious because they feel their lives are in danger; their emotional burden is high and fear dominates the health professionals speak more about the lack of financial resources and logistical gaps that have been further affected due to the pandemic situation; emotional burden is rather reserved and optimistic about the future

With the support of NGOs, most patients have identified possible solutions they can turn to when they do not receive full treatment. These emergency solutions are not made available to the patients by the state authorities, but are the result of the individual efforts of the patients and various social activists involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

In terms of the currently available therapies, most treatments are perceived as modern, effective and with high tolerability profiles. However, access to these modern therapies is still difficult, especially outside Bucharest, and it is the patients who have to insist on more easily administered treatment regimens with fewer side effects.

The HIV/AIDS information and prevention campaigns are considered important and necessary by all participants in the study. Currently, there is no centralized effort in Romania towards HIV/AIDS prevention. The state authorities have difficulties in implementing large-scale education and information campaigns and the NGOs have financial limitations because their efforts are self-sustained without external support.

The context of the Covid-19 pandemic has destabilised the medical routine of the HIV-positive patients, who have encountered multiple difficulties in accessing the medical services and the availability of antiretroviral treatment.

44

IV. Legal research

Section 1: General aspects

1.1 General aspects

The general legal framework applicable to the situation of the persons living with HIV and the fight against the spread of the virus is based on Law 584 of 29 October 2002 on measures to prevent the spread of AIDS in Romania and to protect the persons infected with HIV or suffering from AIDS (“HIV Law”) and its implementing regulation of 24 November 2004 (“HIV Law Implementing Regulation”). The two laws generally concern the division of tasks between various governmental bodies and state institutions, but also include a number of provisions concerning the rights and obligations of the persons living with HIV and issues of confidentiality in the medical and professional sphere. The HIV Law regulates the process of developing National Strategies for the Surveillance, Control and Prevention of HIV/AIDS (“National Strategies”). According to an earlier form of the HIV Law and the still in force form of the Regulation on the Implementation of the HIV Law, the National Strategies should be developed by the National Commission for the Surveillance, Control and Prevention of HIV/AIDS (“National HIV Commission”).1

A system of legislation for ensuring THE access to medical treatment is in place, starting with Law 95/2006 on health reform (“Health Law”), which includes the HIV/AIDS-specific treatment within the intervention areas of national public health programs (“National Public Health Programmes”). These national health programs are key to providing the necessary funding for free access to the appropriate treatment – they are drawn up periodically by the Ministry of Health with the participation of the National Health Insurance Fund. In the field of HIV/AIDS, there is a separate national program called the National Programme for HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance and Control. An important role in regulating the access to medicines is played by the technical norms for the implementation of national public health programs (“Technical Norms for the Implementation of National Programmes”). There is also Law 46/2003 on

1. The legal situation of the National HIV Commission is unclear given the abrogation of Article 4 of the HIV Law, but the other references and powers of the Commission remain in force. These issues are discussed in Chapter 2.5 below

46

patients’ rights, a normative act which establishes the rights of the beneficiaries of health services.

In terms of social protection, the persons living with HIV or AIDS receive a monthly food allowance – the methodology for granting this is established by the order of the Minister of Labour and Social Solidarity and the amount is set by government decision. Currently in force is the Methodology for granting the monthly food allowance to adults and children infected with HIV or AIDS and for controlling its use by those entitled to it, approved by Order no. 223/2006 (“Methodology for granting the food allowance”) and its amount is currently established by Order 1177/2003 approving the amount of the monthly food allowance for persons infected with HIV or AIDS (“GD on Food Allowances”). In the case of children for whom special protection measures have been established, the sum of the amounts due under Law 272/2004 on the protection and promotion of the rights of the child (“Law on Child Protection”) is increased by 50% in the case of children infected with HIV or AIDS.

Romania’s anti-discrimination legislation, specifically Ordinance No 137 of 31 August 2000 on the prevention and sanctioning of all forms of discrimination (“Anti-Discrimination Law”), explicitly states HIV status as a characteristic in relation to which discrimination is sanctioned.

In the area of criminal law prosecution, Romania continues to criminalise the “transmission of AIDS” through the offence of “transmission of acquired immune deficiency syndrome” in Article 354 of the Criminal Code. At the same time, the Criminal Code provides as an aggravating circumstance the commission of other offences for reasons related to HIV/AIDS infection and establishes the restriction of the exercise of the rights of persons infected with HIV/AIDS as a separate ground for the offence of abuse of office.

1.2 HIV law and main legal milestonese

From a formal point of view, the HIV Law sets out the main coordinates of the Romanian state’s response to the spread of the virus and the protection of PLHIV:

(i) Assignment of ministries and public authorities – designates the main State authorities with responsibilities in this area, in particular2:

2. The current names of the relevant entities at the time of drafting this material are used

47

Ministry of Health

Ministry of Labour and Social Solidarity – under which the Authority for the Protection of Persons with Disabilities (also designated) operates

Ministry of Family, Youth and Equal Opportunities – under which the Authority for the Protection of Children’s Rights and Adoption operates

Ministry of Education

The following are also designated:

National Health Insurance House

Romanian College of Physicians

Romanian College of Pharmacists

County and Bucharest Public Health Directorates

Hospitals (public or private) and schools (public or private).

(i) Establishment of the National HIV Commission – the original version of the HIV Law established the National HIV Commission, an inter-ministerial body to plan and monitor the implementation of the Government’s HIV/ AIDS policy.

(ii) Establishment of formal measures and objectives – the law establishes two categories of measures:

Measures of preventing the transmission of HIV infection – which generically include:

Educating the population on how HIV is transmitted

Mandatory provision of the necessary precautions and means in all health facilities

Mandatory provision of means to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection

Obligation for all mass media to promote the use of condoms free of charge on a quarterly basis to prevent sexual transmission of HIV infection

The provision by the employers of the post-exposure prophylaxis free of charge

Social protection measures – which follow the two main coordinates: Unrestricted and unconditional right to work and non-discriminatory career advancement

Respect for the right to education

48

In concrete terms, however, while the HIV Law establishes the right to a monthly food allowance, the amount of which is set by government decision.

(iii) Regulation of confidentiality relationships – the law sets out the principles of the right to confidentiality and the obligation of the employers, officials and employees of the health networks to respect this right. On the other hand, the law establishes the obligation of the patients to inform the health care personnel of their HIV status.

(iv) Financing the prevention activities and protection measures – the law states that the budget of each relevant ministry must include a separate chapter for financing prevention, education and social protection activities. At the same time, the law establishes that therapeutic and health care activities shall be carried out from the budget of the Ministry of Health free of charge

1.3

Allocation of tasks to authorities according to the HIV Law Enforcement Regulation

The HIV Law Enforcement Regulation is the legal instrument that sets out the government institutions with responsibilities for the HIV Law enforcement.

The table below illustrates a number of actions and tasks prescribed by the legislation in which the various authorities are charged with duties:

Duties

Preparation or, where appropriate, participation in the preparation of draft legislation governing:

a) measures to prevent HIV transmission;

(b) social protection measures for persons infected with HIV or AIDS;

(c) confidentiality of data relating to HIVinfected persons;

Responsible authority3

Ministry of Health Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family Ministry of Education and Research Ministry of National Defence Ministry of Administration and Interior Ministry of Justice

3. The names in the tables are based on the names in the legislation - their powers have been transferred through successive takeovers of portfolios by the current authorities.

49

d) appropriate treatment of HIV-infected persons eligible for treatment;

(e) specialist training and the development of medical research in this field;

(f) financing of activities for the prevention of HIV transmission and treatment of PLHIV, as well as social protection measures for the affected persons.

Elaboration and proposal to the Government for the approval of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy

Ministry of Transport, Construction and Tourism

General Secretariat of the Government Chancellery of the Prime Minister

Development of the national HIV/AIDS prevention, surveillance and control programme and measures to reduce the social impact of HIV/AIDS cases.

National Commission for HIV/AIDS Surveillance, Control and Prevention Ministries and institutions with responsibilities in the field and/or with their own health network

Carrying out research in order to determine the groups at risk

Ministry of Health, in collaboration with:

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family, Ministry of Education and Research, National Youth Authority, National Agency for Sport, National Authority for Child Protection and Adoption, National Authority for Persons with Disabilities, National Health Insurance House, Romanian College of Physicians, Romanian College of Pharmacists

50

Informing the population and training the medical and auxiliary personnel on universal precautions and means to prevent HIV transmission

Informing the population and training the medical and auxiliary personnel on universal precautions and means to prevent HIV transmission

Mandatory means of preventing motherto-child transmission of HIV infection, including:

- measures of ensuring the free counselling and testing of pregnant women

- provision of antiretroviral treatment for pregnant women infected with HIV or AIDS

- clinical and laboratory monitoring of newborn babies born to mothers infected with HIV or AIDS, - and any other measures necessary for lowering the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection

Ministry of Health Ministry of Health Ministry of Health

Development of a list of professions and activities at risk of occupational exposure to HIV infection

Monitoring of compliance with the obligation of all health facilities and physicians, regardless of their form of organization, to admit and provide medical care for HIV/AIDS-infected patients and

Ministry of Health Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family

Ministry of Health National Commission for HIV/AIDS Surveillance, Control and Prevention

51

take appropriate action against those guilty of non-compliance with this obligation

Activities aimed at ensuring the continuous training of health workers in the field of HIV infection

Ensuring the appropriate level of amounts allocated from the budget of the Single National Health Insurance Fund for specific medicines and healthcare materials to be acquired for this purpose and carrying out their acquisition

Ministry of Health

Ensuring, monitoring and controlling the use of amounts allocated from the budget of the Single National Health Insurance Fund, monitoring, controlling and analysing the physical and efficiency indicators during the implementation of the programmes

Providing information every six months to the Health Committees of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies on the indicators of the sub-programmes for the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, the way in which the specific therapy and of the associated infections have been provided

National Health Insurance House

Monitoring compliance with the right to work of PLHIV or suffering from AIDS

National Health Insurance House and the county health insurance funds

Ministry of Health

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family, through the Labour Inspectorate

52

Providing free of charge to persons infected with HIV or suffering from AIDS all information and professional counselling services, including job search according to the stage of the disease, according to the law

Informing the employers about the rights and obligations of the employees infected with HIV or suffering from AIDS and their obligation not to discriminate on grounds of health

County and Bucharest Employment Agencies

Educating the employees on the right to free post-exposure prophylaxis

Ensuring the payment of monthly food allowances to adults and children infected with HIV or suffering from AIDS who are hospitalized, institutionalized and in state outpatient clinics, in accordance with the methodology approved by order of the Minister of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family, together with Ministry of Health,

Conducting annual sociological research aimed at monitoring the number of recipients of monthly food allowances, their family and social situation and will advance proposals for the development of new social protection programmes and measures

Dissemination of educational and information programmes on HIV prevention and appropriate behaviour towards persons living with AIDS in all state

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family

Ministry of Education and Research, together with:

53

and private school establishments and free, universal and unconditional access to this information for all young persons attending a level of education.

Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and the Family, National Youth Authority, National Agency for Sport, National Authority for Child Protection and Adoption,

National Authority for Persons with Disabilities

Ensuring the introduction into the curriculum, differentiated by school cycles, of a health education programme, including, inter alia, a separate chapter on HIV/AIDS, as well as the introduction into the teacher training/continuing education system of general knowledge on HIV/AIDS, the protection of the affected persons and the behaviour towards them and the development of extra-curricular and extra-school activities, and ensuring the monitoring of the implementation of these programmes

Promotion in the educational establishments of the development of an appropriate attitude towards persons infected with HIV or suffering from AIDS in order to eliminate their marginalisation and discrimination and to create a tolerant environment towards them.

Ministry of Education and Research

Ministry of Education and Research, through the county school inspectorates

54

Section 2: Medical legal framework

2.1

Ensuring the universal provision of treatment

The universal access to treatment for persons living with AIDS was introduced in 2001 and the programme has been recognised as a model in the region3. The HIV law currently provides that specific antiretroviral medication and HIV/AIDSrelated diseases are established free of charge4. The HIV Law also stipulates that the financing of therapeutic and health care activities shall be provided from the budget of the Ministry of Health or, where appropriate, the National Health Insurance Fund5

The Health Law includes a number of activities of public hospitals that can be financed from the state budget and these include HIV/AIDS programmes6 Specifically, the subject matter and funding mechanisms are determined by: National Public Health Programmes developed periodically by the Ministry of Health with the participation of the National Health Insurance House – in this case the National HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance and Control Programme; and Technical Norms for the Implementation of National Programmes issued by the Ministry of Health

At the time of writing, the technical rules in force are those of 30 March 2017, established for the years 2017 and 2018, their applicability being extended successively – according to the last extension, they remain in force until the end of the month in which 60 days after the date of entry into force of the state budget law for the year 2022 will have passed7

This system of rules is complemented by:

Government Decision No 720/2008 approving the list of international common names of medicines available to the insured persons, with or without personal contribution, on prescription, under the social health insurance system, as well as the international common names of medicines available under the national health programmes; and

Order of the Minister of Health and of the President of the National Health Insurance House No 1.605/875/2014 approving the method of calculation, the

3. UNAIDS Country Progress Report on AIDS – Reporting Period January 2015 – December 2015

4 Article 10 of HIV Law

5 Article 16 (2) of HIV Law

6 Article 193 (2) (h) of Health Law

7. Article II of the Order of the Minister of Health No 1087/2017

55

list of trade names and the settlement prices of medicines to be granted to the patients under national health programmes and the methodology for their calculation.

2.2 Distribution of medicines exclusively in hospital pharmacies

According to the rules in force8, in contrast to the previous regulations9, the medicines for the outpatient treatment of HIV/AIDS patients are distributed through the closed-circuit pharmacies of the health units through which these programmes are implemented, on the basis of a prescription/medical order10 As such, medicines cannot be obtained free of charge through the private pharmacy networks and the beneficiaries have the only option of purchasing medicines in the relevant hospital pharmacies.

This issue – the need to obtain medicines in hospital networks, which often involves the access to wards, or queuing designated for persons living with HIV –has been identified as a source of anxiety for the beneficiaries, jeopardising the legal right to the confidentiality of the medical status.