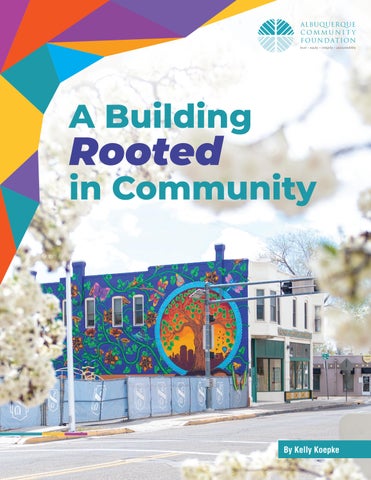

A Building Rooted in Community

By Kelly Koepke

THE CHAMPION BUILDING, the permanent home of the Albuquerque Community Foundation since 2012 at 624 Tijeras NW, demonstrates the hardworking nature of immigrants to the United States who endured hardships to provide livelihoods for their families. The enduring structure, today more than 120 years old, also exemplifies the value to a community of preserving its architectural legacy while anchoring a more than 40-year-old organization within a historic downtown neighborhood.

The Neighborhood Store

Alessandro Matteucci first came to America in 1899 from Luca, Italy, as part of a wave of Italian immigrants brought to the expanding West by the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. When he arrived, Albuquerque had only about 6,200 residents. As with many new arrivals Matteucci counted on family connections to establish himself. He worked as a clerk at his uncle’s Porto Rico Saloon and Grocery Store located near the present site of the Albuquerque Little Theater. The store, in what was called “New Town” Albuquerque to differentiate the city’s expansion eastward from Old Town, sold the community Italian wine and olive oil and other imported goods as well as staples like coffee, sugar and flour. The Porto Rico also acted as a proto-travel agency, selling steamship tickets back to Italy. Soon after his arrival, the industrious Matteucci took over the business.

Matteucci’s achievements and ambitions could not be satisfied with one store. The Porto Rico simply wasn’t enough. As one of the first Italian immigrants to find success in the Albuquerque grocery and saloon

business, he decided to expand his existing ventures by partnering with another Italian immigrant, Pio Lommori. The men started building the two-story, red brick and stone foundation, Lommori and Matteucci Grocery and Meat Market, in 1902-3. Upon its opening in 1904, the market was within close walking distance of Immaculate Conception Church and the devout Catholic ladies who needed groceries (and gossip time) after mass. With entry doors facing the southeast corner of Tijeras and Seventh Street, the store’s large windows fronted Tijeras with displays of the variety of goods for sale. The stand-up basement, a rare feature of Albuquerque buildings even today, provided cool space for wine making and storage before air conditioning.

Like most of the other grocery stores in the city, door-to-door delivery was the norm, with customers calling in by telephone or sending children with their daily and weekly orders. The horsedrawn delivery wagons, laden with fruits, vegetables, meats and dry goods, many imported from Italy, would make the rounds of neighborhoods throughout the city. The wagons (and later, trucks) were loaded through large double doors (today preserved in forest green but no longer functional) on the Seventh Street side.

Though the hitching posts to which horses would be tied are long gone, metal rings in the sidewalk remain a reminder of the original mode of delivery transportation.

In the book “Italians in Albuquerque,” a caption on a 1910 photograph describes the delivery process, as told by Mario Menicucci. “Nobody ever went to the grocery store. The grocery stores all delivered. The telephone was it. My mother called up, in Italian, and put the order in. The store clerk would make up a bill and keep the bill there until the end of the month. Anything she needed, she would just call up the store. She’d give them the order, and they would deliver in a wagon, on a bicycle, or, in later years, in a truck.”

The Foundation still has one of the store’s account ledgers, a fragile book filled with yellowing pages with Italian notations of who ordered what, when and the tallied amount, donated by the Marianetti family. These stores, and certainly the Lommori and Matteucci Grocery, were more than retail outlets. They were community hubs, where neighbors gathered to socialize. Often, relatives of the owners would find their first employment behind the counters, like Matteucci, or as delivery drivers. That was indeed the case in 1907, when Lommori exited

the partnership. Matteucci brought his brother Amadeo on board, renaming the enterprise the Champion Grocery and Meat Market. At this point, signage (as noted in photographs) was written in both Spanish and English to appeal to the city’s Hispanic community. The store became one of the most popular in the city, which now counted about 10,000 inhabitants.

When the Champion building was first built, the ground floor was designed as retail space, while the second story was configured as living quarters. This common practice at the time has all but disappeared in the city. Four handsome bay windows on the west side provided upstairs residents with bird’s eye views of the neighborhood, while a diamond shaped, multi-colored stained glass window allowed the setting sun to cast rainbow hues into the parlor room. Cast stone decorative courses and mosaic tile work above and below the first floor display windows added attractive touches. Based on photographs dated between 1906 and 1907, the Matteucci brothers expanded the building, adding a two-story east wing that increased both the retail and residential space. Shortly afterwards, a fire destroyed the new wing, which was promptly rebuilt.

While the east wing added space and continued the ground floor’s large display windows, only one more bay window was added to the eastern end of the second

story’s north facing façade. As before, the second story of this new wing was designed to be residential apartments, and a garage and apartment to the south were added between 1919 and 1924.

Alessandro and his family lived in the original west wing second floor quarters until about 1910, when they purchased a two-story house across the street. Alessandro’s success as a business owner also allowed him to purchase an automobile in the 1920s, a luxury for most people at the time.

In 1914, the fraternal Matteucci partnership dissolved when Amadeo left to go into business with another immigrant store owner, Michael Palladino. They opened the rival Matteucci and Palladino, just one block away (now the former First Financial Credit Union building). The presence of competition did not deter the larger Champion’s prosperity, though, and Alessandro continued to operate the store until his retirement in 1938.

Building of Many Uses

In the more than 120 years since the Champion Building’s construction, it housed grocery stores and meat markets on the ground floor until the 1960s. After that, a succession of retail and service establishments, including the Gypsy Beauty Salon, Orr Refrigerator Service, Holland and Globe Tailors, the Korea Karate Institute, and architects’ offices, among

other businesses, found homes in the structure.

A notable business from 1978 to the early 1990s was The Uniform Store, provider of parochial school clothing and fabric. Today, nostalgic individuals still visit the Foundation’s lobby, sharing that they would buy their uniforms there for next door’s St. Mary’s Catholic School. Douglas Wright-Meyer, son of the original owner Patrica Meyer, wrote on a Facebook post in 2023,”If you wore school uniforms from 1977 to 1995 in Albuquerque, you surely purchased them from her business…”

One of the architects who called the Champion Building home was Isaac Benton, who also served as an Albuquerque City Councilor representing Downtown. He described school children lining the sidewalk as they waited to enter St. Mary’s, sometimes taping on the windows to gain his attention. Though he often talked with owners Paul and Patti Marianetti about purchasing the building, added to the New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties in 1977 as significant historically and culturally, and part of the Historic Landmarks Survey Register for the City of Albuquerque, it was not to be.

“I was surprised that Paul [Marianetti] was going to donate it. But if it had to go somewhere, I was pleased that the Albuquerque Community Foundation got it and that it was not going to be sold for speculative purposes. It could have been torn down, or used neglectfully until no more use was left. As an architect, and someone who worked in the building for years, I had a keen, critical eye towards what was being done in the renovation. I think they did a beautiful job keeping the sense of the building,” Benton says.

The building remained in use and in the family, through Alessandro Matteucci’s daughter Yolanda Marianetti and her son Paul, until 2010. With offices on the street level and residential units above, the upper story saw a rotation of residents

The Senator and the Stained Glass

The beautiful western facing multi-colored, diamond shaped stained glass window that created rainbow beams in the second story parlor room was at one time covered over, as it was prone to leaking and breakage. Thelma Domenici, godmother of Albuquerque Community Foundation CEO Randy Royster, recounted to him that her parents, Cherubino “Chope” and Alda Domenici, both immigrants from Italy who ran their own grocery store, raised their family in the neighborhood. Apparently, the window was an attractive target for the baseball of her brother to get the attention of the children who lived there.

“When the Foundation got the building, I brought Thelma for a tour. She had fabulous stories about the building, as the Domenicis lived close by when she was growing up. I had showed her pictures of the building, and she said there used to be a window that didn’t exist in the photos. Maria Matteucci, wife of Alessandro, had commissioned the window in colors to match the furniture and décor of the room, the family parlor.

“As a boy, Thelma’s brother Pete liked to play with the children who lived in the building. In fact, Pete’s nickname was Bocce (both because of his love of “ball” and for the shape of his head). One day Pete tossed his baseball up at the window to alert his friends and broke it,” said Royster.

During the building’s renovation in 2010-12, this stained glass window was commissioned and donated by SMPC Architects in similar colors and replaced as an homage to the building’s original charm and the mischief of the little boy who would become United States Senator Pete Domenici, who served New Mexico for a record six terms from 1973 to 2009.

who valued the location and walkability to downtown Albuquerque’s business scene, restaurants and artistic offerings, and public transit to take them throughout the city. For many years, the University of New Mexico housed scholarship architecture graduate students there, including the eventual husband of the interior designer charged with bringing the Champion back to life.

Serendipity Four Times Over

In 2010, the Champion Building’s aging owners Paul and Patti Marianetti decided to donate the property to the Albuquerque Community Foundation. The Marianettis still lived across the street in a house that his grandparents, Alessandro and Maria Matteucci, had purchased. The gift came with one stipulation: that it be renovated and used as a permanent home for the Foundation.

“My grandfather got his start here, made his living here and lived most of his life here,” said Paul Marianetti in an interview published in the Albuquerque Journal. “We really wanted to pay back the city that has been very good to us.” The Marianettis also found the tenants of the Champion’s apartments new homes before the official transfer to the Foundation.

But the story of how the Champion became the permanent home of the Foundation can only be told as a series of serendipitous events. Two contemporaneous conversations occurred in 2010. The first was between engineer and then Albuquerque Community Foundation Trustee and Chair of the Board, Vic Chavez, and the Marianettis.

“I got a call from Paul, who is the cousin of a good friend, about him possibly donating the building. He and Patti and I toured the building,” says Chavez, who also happened to be a structural engineer and founder of Chavez-Grieves

Consulting Engineers. “The first floor was in good shape, but the four second floor apartments and the basement were rough. We saw water damage, rotten wood and structural challenges. There’s a thing called dead-load deflection. For example, when you put weight on the floor, it’ll deflect half an inch. Over the years, due to dead load deflection, it becomes three quarters of an inch. During my first visit with Paul, we discovered excessive loads and uncomfortable deflections. As we talked, I said that the Foundation would also need a donation of cash to help with the needed structural renovation. They agreed.”

The second discussion happened at the same time between Randy Royster, Foundation CEO, and the Matteucci’s attorney Tom Blueher, a former Foundation Trustee, whose wife Francesca Matteucci Blueher, was a cousin of Paul’s. The two had discussed the possibility of the building’s donation to the Foundation. “I called him [Vic] about hearing from the Marianetti’s attorney out of the blue and he laughed his big laugh. I said, what are you laughing about? He said, yeah, I was just over there with Paul and Patti. It was one of those very Albuquerque and New Mexico coincidences that often mean that something was meant to be.”

In a third instance of serendipity, when Royster had interviewed for the Foundation’s CEO position five years earlier, one of his stipulations in taking the job was that the Foundation commit to finding a permanent home. The organization had been leasing strip mall office space, which had been generously provided by the Blaugrund family, long term significant donors to the Foundation. Royster’s concern was that a strip mall, with its constantly changing tenants, did not appropriately reflect the Foundation’s mission of legacy in perpetuity. How could they profess their intention to stick around when their office space was temporary? Another of Royster’s conditions was that

the Foundation’s permanent residence be in the Downtown city center, and, if possible, in a historic building.

“When this opportunity [to receive the Champion building as a donation] arose, it was right in line with what I had envisioned,” he says. “The opportunity to own, occupy, and be stewards of a historic property in downtown Albuquerque directly aligned with the vision and mission of the Foundation.”

The cherry on the serendipity cake was three-fold, revealing the depth and diversity of the Foundation’s Board of Trustees. First, Vic Chavez, donated his time and engineering expertise to provide construction oversight of the project while serving as Foundation Board President at the time. Second, Kevin Yearout, owner of Yearout Mechanical and also a Board Trustee during this period, also provided his services at no cost. Finally, Royster’s own background included not only his

profession as an attorney, but his former background in real estate development and construction management. His experience perfectly positioned him to become the owner’s project manager for the extensive renovation project. He spoke and understood the language of contractors and builders.

Renovations, Surprises and Community Support

As might be expected from a century-old, 6,000 sq. ft. structure, the Champion Building needed extensive renovation to create the Foundation’s permanent home with office space, conference rooms, a kitchen and other requirements. An initial estimate of $975,000 would include abatement of hazardous materials and the desire to provide better access to the entire building. Selective demolition of the plaster ceilings

Whad revealed serious stress issues with the roof and second floor framing. At every turn, another issue was uncovered, and additional costs added to the total.

The building donors had provided $150,000 as seed money for a capital campaign to complete the extensive structural stabilization and reconfiguration of the space. The Foundation planned to raise an additional million dollars by seeking sponsorships for everything from conference rooms to offices to the new elevator. Though the building was listed on the state register for historic properties, there were no tax credits available to offset the cost.

Fortunately, donors and sponsors began to step up, as they recognized the value of the Foundation’s opportunity to own, occupy and be stewards of an historic property in downtown Albuquerque. SMPC Architects, led by architect and Foundation Trustee Glenn Fellows and interior designer