Best Of The Mountain West

CHERRY CREEK MALL | PARK MEADOWS FORT COLLINS | FLATIRONS | BOULDER

Introducing ELIXIR GOLD

Colorado State is committed to student success before and after graduation. On-campus academic support and career resources enable CSU students to graduate with the confidence, skills, and spirit to change the world.

Our third annual celebration of the people, places, and things changing the way we live for the better—from a megasculpture in the Nevada desert to a Montana bison preserve recently returned to Indigenous control.

EDITED BY JESSICA LARUSSOBakeries are having a mo ment, thanks to Denverites’ appetites for carb-loaded comfort and a pandemicdriven rise in storefront-free operations. We nibbled our way through fluffy cupcakes, vanilla-creamstuffed buns, and crackly sourdough loaves to find the tastiest goodies in and around the Mile High City.

BY PATRICIA KAOWTHUMRONG & RIANE MENARDI MORRISON

Denver has been a hot spot for millennial transplants. But what happens when the generation born between roughly 1981 and 1996 suddenly becomes the one that can’t afford to stay?

BY ROBERT SANCHEZAt National Jewish Health, the nation’s leading respiratory hospital, we bring doctors, scientists and caregivers together to find answers, develop treatments and solve the medical challenges of today and tomorrow. From providing care for adults and children with complications from COVID, to addressing the needs of patients with lung, heart, immune and related diseases — our experts work within our communities and across the nation.

Our research breakthroughs are improving and saving lives around the world, while our innovative care leads to extraordinary outcomes.

To learn more or make an appointment, call 800.621.0505 or visit njhealth.org.

Following two years of pandemicinduced closeness, we could all use a little space. This holiday season, we suggest giving the gift that says, “Please leave.”

CBS4 News’ Jim Benemann and 9News Mornings’ Gary Shapiro both announced that they are retiring soon. Before the celebrated newsmen sign off, we asked them to cover one last story: their own.

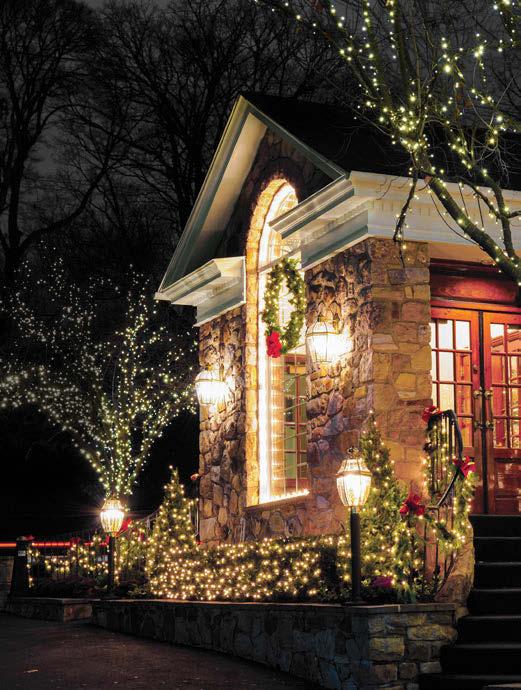

Shawn Sealy, owner of Little ton’s St. Nick’s Christmas and Collectibles, shares decorating tips for keeping the stress low when putting the lights high.

Instead of hibernating when the mercury drops, take your hatch lings (and our bird-watching field guide) to Barr Lake State Park.

One year after CharlestheFirst’s death, Denver artists reflect on the ways the electronic musi cian continues to inspire them.

Self-care mecca Nurture has a new way to indulge: dinner at Rewild.

Meet Adam Freisem, the executive chef behind Castle Rock’s beloved Manna Restaurant.

Chef Zin Zin Htun introduces patrons to the culture and cuisine of Myanmar.

40 REVIEW

The Cole neighborhood gets a taste of Brasserie Brixton’s refreshed bistro fare.

BY ALLYSON REEDYUnder financial strain and a heavy mental load, ski patrollers are grinding to keep the slopes safe—and to make their profession more viable.

BY JAY BOUCHARDJerome Osentowski is known the world over as a pioneer of permaculture. But can the Eagle County resident survive a challenge from a pest he never anticipated?

BY CHRIS WALKER

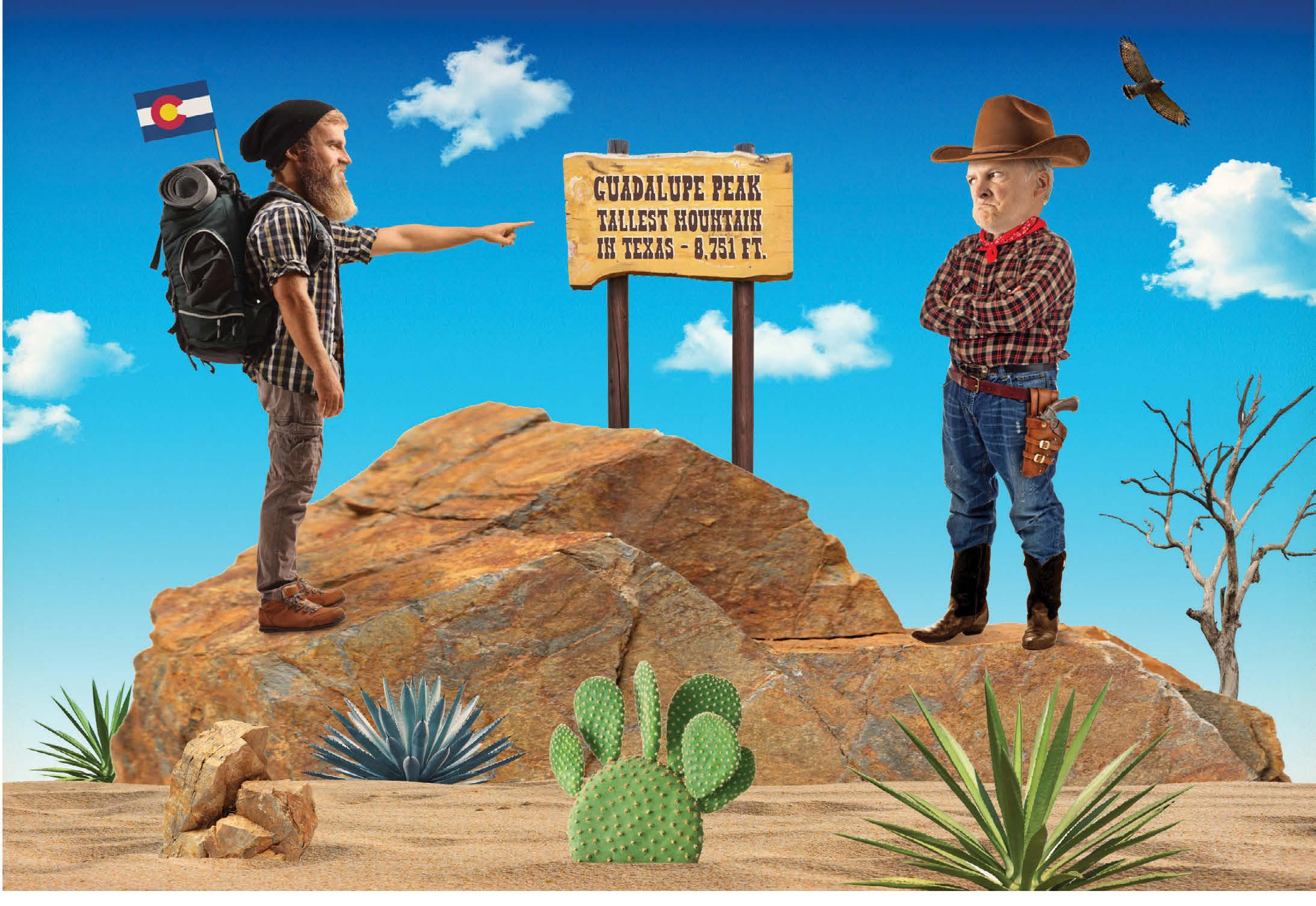

Four fun places in Texas where you can escape the cold this month—and annoy the locals while you’re at it.

If you’re ready for merry making or searching for good tidings, you will find places that light up your spirit this season in downtown Boulder. With local shops stocking unique gifts; cozy restaurants serving holiday cheer; and magical moments around every corner, come discover your happy place to fill your heart with holiday wonder.

Find your holiday happy place in Downtown Boulder.

VisitDowntownBoulder.com

CU Medicine always puts our patients first. With nationally recognized physicians, we CU and treat you with the most advanced technology—and provide personalized, comprehensive care you can trust. Because at CU Medicine, we CU as more than a patient. We CU as the inspiration behind everything we do.

We CU as our #1 priority. Find a provider near you at CUmedicine.us.

A one-year subscription to 5280 costs $16 for 12 issues. A two-year subscription costs $32. Special corporate and group rates are available; call 303-832-5280 for details. To start a new subscription, to renew an existing subscription, or to change your address, visit 5280.com/ subscribe; call 1-866-271-5280 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. EST Monday through Friday; or send an email to circulation@5280.com.

Letters to the editor must include your name, address, and a daytime phone number (all of which can be withheld from publication upon request). Letters may be submitted via regular mail or email (letters@5280. com). To have a restaurant considered for our Dining Guide, contact us by phone or email (dining@5280.com) to receive a submission form. We also encourage you to contact us if your experience at a restaurant differs significantly from our listing. Information for these sections should be subm itted at least six weeks before the issue’s cover date.

Writer’s guidelines can be found online at 5280.com/writers-guidelines. To suggest a story idea, email us at news@5280.com.

offers businesses the most costeffective way to reach Denver’s upscale consumers. Information about advertising is available on the web at 5280.com/ advertising. Call 303-832-5280 to request a printed media kit.

actively supports organizations that make our city a better place to live and work. Submit sponsorship proposals to Piniel Simegn, director of marketing, at sponsorship@5280.com.

Adults don’t often make wish lists, even if they’re feeling confident that Santa would characterize them as nice. But I have a friend who likes to say that “if you want something, you’ve gotta put it out into the universe.” Thought leaders in the self-help space (see: Deepak Chopra) would probably call this “manifesting.”

I’m not typically prone to woo-woo philosophies—in fact, my pragmatism enjoys near-mythic status among those who know me—but as we entered the holiday season and began to wind down yet another challenging year, even I found myself wondering if there were any harm in this if-you-think-it-it-will-come notion.

On a crisp November day, I decided a little chat with the cosmos couldn’t hurt. My index of desirables wasn’t to be about me (although I could use some help with that novel I’ve been wanting to write). Instead, I would focus my good juju on the issues I’d encountered—and lain awake thinking about—as a journalist and editor in Colorado over the past year. And so, as I sat in my backyard and watched the leaves fall, I came up with the following requests.

I would love it, I said to no one in particular, if those made lonely by the isolation of the pandemic could find the outstretched hand of a friend. If Marshall fire survivors could get the support they still desperately need, nearly a year later. If Colorado’s underrepresented voices could more frequently find welcoming audiences. If we could all sacrifice just a little comfort and convenience—and the almighty dollar—to protect our state’s natural beauty. If we could simultaneously recognize the root causes of crime and address the state’s sharply rising rates. If leaders could put in place smart policies that mitigate Colorado’s housing crisis. If Coloradans could stand up to safeguard the rights we believe we are afforded as Americans. And, maybe most important, if we could all treat each other with kindness and dignity, even when we disagree.

My short list is a tall order. But, hey, I’ve put it out there now. Maybe the powers that be will answer. If not, I probably still have time to send a letter to old Saint Nick.

Jay Bouchard Freelance Writer

Bouchard put his ski skills to the ultimate test when he tried out for Eldora Mountain’s ski patrol (“The Price Of Powder,” page 44). But the New Hampshire native was confident his East Coast upbringing had prepared him well.

EAST

“East Coast skiers don’t complain about conditions. And I’m not trying to start anything, but there’s a reason Mikaela Shiffrin moved to the Northeast to train as a kid. OK, maybe I am tr ying to start something.”

”Most of your sources are very cool people and very good skiers. It’s hard to be objective when you want to quit writing for a living and hang out with them instead.”

BEST SKI RUN IN COLORADO “Do you actually think I’d let you print that?”

Email: lindsey@5280.com

Twitter: @linzbking

Still looking for last-minute gifts for your loved ones this holiday season? Don’t panic. Head to 5280.com for a comprehensive list of the best presents from local companies for every kind of Coloradan, from skiers and hikers to dog lovers and, well, dogs.

ICON Eyecare’s team shares one mission: To improve people’s lives through better vision. As a medical ophthalmology provider, ICON is committed to providing you with expert eye care and quality lens-based and laser vision correction options including EVO ICL, LASIK, PRK, and CLE. EVO ICL is a vision correction option that implants a lens in the eye, instead of altering the shape of the cornea as with LASIK or PRK. ICON’s Dr. Eva Kim is Colorado’s top ICL surgeon and we are the only provider in Colorado to use advanced testing technology to precisely fit your ICLs. To find out if EVO ICL is the right vision correction option for you, schedule a consultation at one of our 5 Front Range Colorado clinic locations.

The past two-plus years have forced us to become closer than ever with our loved ones. Like, straitjacket close. In other words: You could use some space. Not a permanent split, of course—but a short-term separation? Yes. Please. Now. Our present to you is five gift ideas that’ll make your heart grow fonder by creating temporary distance between you and the rest of your household.

In November, JSX airline began offering direct flights from Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport in Broomfield to Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport five days a week. The Dallas-based carrier flies smaller planes that don’t require passengers to suffer through TSA lines, yet round-trip tickets cost less than $500.

The newest offering from Longmont-based Rossmönster, the Lagom series (from $205 per night) consists of off-roadready rental rigs featuring a hard-walled pop-up camper that could sleep two but would also be supercomfy for one (hint, hint). And the floor-to-ceiling windows provide unimpeded

views of the landscape, which might inspire the gift recipient to remain in the wild for an extra sunset or two.

Galena Mountain Projects, an outdoor retailer in Leadville, has everything you need to encourage your SO to head for the hills, including Arkansas Val ley guidebooks providing local knowledge on the area’s best sunbaked crags and flowy single track. Pair a book with Galena’s 5-9-5 Shirt ($86), a versatile spandex blend with a Western twang, so your loved one can dress the part while exploring.

Give yourself the gift of quiet by sending your budding Dave

Grohl to Drum Box. The threeyear-old company turned two ATM vestibules, in Longmont and Lafayette, into mini drum studios equipped with four- and five-piece kits. Book online (one hour costs $30, but a bundle of 10 one-hour sessions runs $150) and boom: the sound of silence.

Kids are prone to breaking things— like that fancy Apple AirTag tracking device you gave them last Christmas in order to monitor their movements. This year, stick a snazzy, protective case

from Fort Collins–based Otter Box into their stockings to serve as a safeguard. Decorated with vibrant swirls, the company’s new Figura Series option ($20) is made with synthetic rubber and features a handy clip to protect your peace of mind while your kids are out and about—leaving you home all alone.

After more than 30 years in the Denver market, CBS4 News’ Jim Benemann and 9News Mornings ’ Gary Shapiro both announced that they will soon hang up their microphones for good. Before the celebrated newsmen sign off, we asked them to cover one last story: their own. —SC

5280: Finish this sentence. The most accurate thing about the movie Anchorman was…

Gary Shapiro: The most accurate thing in that movie was the mustaches. It was the ’80s. I had one, for sure. And Jim, I know you did, too.

Jim Benemann: Yeah, quick mustache story. When I went to Channel 9 in 1981, they had Ron Zappolo—mustache. They had Greg Moody—mustache. They had John Ferrugia—mustache. Roger Ogden, the general manager, said, “Jimmy, I don’t want to be the mus tache station. Lose the mustache.”

Shapiro: When Dave Lougee became the news director at Channel 9 in 1990, he called me into his office and said, “You know, I think the era of mustaches is over, Gary. I think you need to get rid of the mustache.” I said, “Aw, really?” And he said, “Man, it’s not that good anyway.”

Other than the facial hair, what has been the biggest change in TV news over the past three decades?

Shapiro: The way the internet has affected audiences. Channel 9 in the ’80s used to get about a 50 share on its 10 p.m. news cast [meaning half the households in the Denver market tuned in]. That’s incredible. Now, you’re lucky if you get a six or seven share. I don’t think the stories are all that different. We still try to give people information about their communities in a way that’s understandable and compelling.

Benemann: Local news didn’t just sit back and watch social media explode. Gary’s station was the blueprint in this market for how to be part of that. Now, all the stations have aggressive websites and are figuring out ways to monetize the eyeballs that visit those websites.

Anchorman lampooned the idea of TV newspeople being icons, but what’s it really like being a local celebrity?

Shapiro: Jim is more of a celebrity than I am, so I’ll let him talk about that.

Benemann: I do get recognized, but I am at a point in my life, 66 years old, where people say, “God, I remember when I was a toddler, my mom and dad used to watch you.” It’s a smack in the face that we’ve been at this for a long time.

Shapiro: I decided I wasn’t going to take myself too seriously after a guy came up to me and said, “I recognize you.” I said, “Channel 9?” And he goes, “No, that’s not it. You ever work at the meatpacking plant?”

Shapiro: In 1986, I went to Florida to do a piece on these great kids from Colorado who had won a contest to watch the Challenger space shuttle take off. We all know what happened to Challenger.

Benemann: The one that was such a game changer for our society and our community was the Columbine High School shooting. Sadly, that was just the tip of the iceberg.

Benemann: No. I think the most important emotion I have as I move toward the door is gratitude.

Shapiro: I remember when I started on 9News Mornings, I thought I’d give it a year or two. Thirty-three years later, I still enjoy doing it. Although I am going to enjoy sleeping in.

Hanging holiday lights often begins with Griswoldian ambitions, only for the mediocre results to leave you feeling like the Grinch. To help preserve your festive spirit, we asked Shawn Sealy, owner of Littleton’s St. Nick’s Christmas and Collectibles, for tips to keep the stress low when putting the lights high. —KATIE ROTH

Nothing is more frustrating than purchasing lights and then, after you’re on the ladder, discovering you need more. Whether trying to illuminate a porch, roofline, or tree, having an accurate idea of the feature’s di mensions will save you a return trip to the store during an already busy time of year.

The right amount of tree lights can turn ordinary displays into regular Rudolphs. The general rule of thumb is about 100 bulbs per foot for pines (so a five-footer needs 500 bulbs) and a little less for deciduous trees; wrap the trunks as tightly as possible. Canopies, however, look better with just a glimmer, so use a strand with bulbs that are two feet apart.

Don’t add to the spike in ER visits during the holidays. To reach higher places, such as branches or peaks in rooflines, use a paint roller with an extension pole attachment. “It makes this awesome install hook for lights,” Sealy says. Those with children and pets will want to stake cords for yard decorations to eliminate tripping haz ards. Elevate cords by hanging them within bushes or securing them to trees to protect them from moisture at the ground level.

Inflatable decorations are a fun and relatively inexpensive way to up your game, but blow-up Frosty requires careful maintenance to ensure a return performance next season. (Pro tip: Roll, don’t fold, when you store inflatables.) Even with the best care, inflatables will only last a few years; fiberglass decorations can endure for decades, though they are more costly.

Replace every third or fourth bulb of a traditional strand with a twinkle bulb to give your display extra flair. Just be sure they’re energy-efficient LEDs, rather than old-school, power-sucking incandescents. (That advice goes for all your lighting paraphernalia.)

Discover Western Nestled in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, Western Colorado University delivers small class sizes, engaging faculty, career preparation, and a robust liberal arts and STEM curriculum to 3,000 intellectually curious students. With access to over 2 million acres of public land, 700+ miles of single-track trails and two ski resorts within an hour of the university, you’ll have the chance to pursue your outdoor passions while working toward a degree in one of 100+ academic areas.

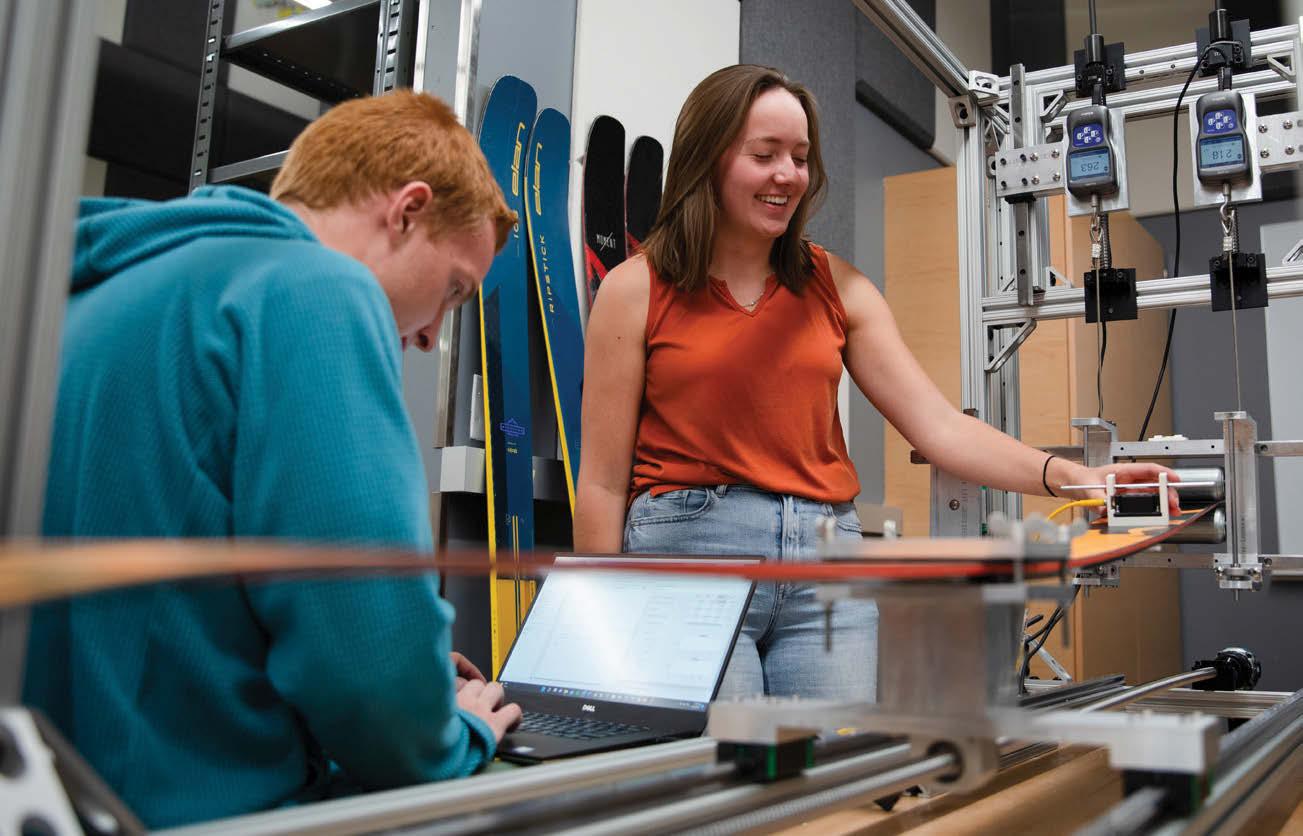

Earn a University of Colorado Boulder engineering or computer science degree while enjoying personal attention from faculty, access to cutting-edge lab facilities and the unbeatable natural surroundings of Western Colorado University.

Head to western.edu/rady to learn more about the partnership program, our unique areas of specialization, and opportunities for program-specific financial aid.

Instead of hibernating when the mercury drops, take your hatchlings (and this field guide) to Barr Lake State Park.

These medium-size ducks from the boreal forests of Canada dive underwater to find their food. Wait about a minute, and they’ll pop back up.

This bird’s bright yellow eyes stand out against the snow. They also have a distinctive, bulbous head and a small beak. Males feature black-and-white bodies with iridescent green heads. Females have gray-brown bodies and brown heads.

You’ll have the best luck finding these smaller song birds by wandering through the cottonwood groves along the nature trail south of the Barr Lake Nature Center. Be sure to keep your eyes down, though. The charismatic junco is most likely hopping around near the low-lying shrubs and tree trunks.

What to look for: Although there are several variations of this mediumsize sparrow, the most distinctive is the Oregon form, denoted by its dark black head, pink bill, and white outer tail feathers.

“The number one draw for Barr Lake in the winter is bald eagles,” Doxon says. America’s mascots move to Colorado when the weather turns cold because their home lakes freeze over, making fishing difficult, while our lakes often do not.

Although birding is considered a pastime for boomers, it’s an ideal excursion for kids, too, says Sarah Doxon, education programs manager for Bird Conservancy of the Rockies: “Not only does it get them outside...it gets them noticing the world around them.” There’s no better time to introduce your little ones to the hobby than December, when northern birds move to Colorado for the season, and the conservancy is hosting two events for kids at Barr Lake State Park in Brighton: the Christmas bird count (December 3) and a winter birding camp (December 28 to 30). If you go on your own, though, you don’t have to wing it. Use

—MALISSA RODENBURGWhat to look for: Juve nile bald eagles can easily be misidentified as golden eagles because they don’t start to look like the distin guished figures we know until they are three to five years old. Some telltale differences: Goldens have feathered legs; balds do not. Goldens have a uniform dark breast and belly, while balds are mottled brown and white.

fig.

fig.

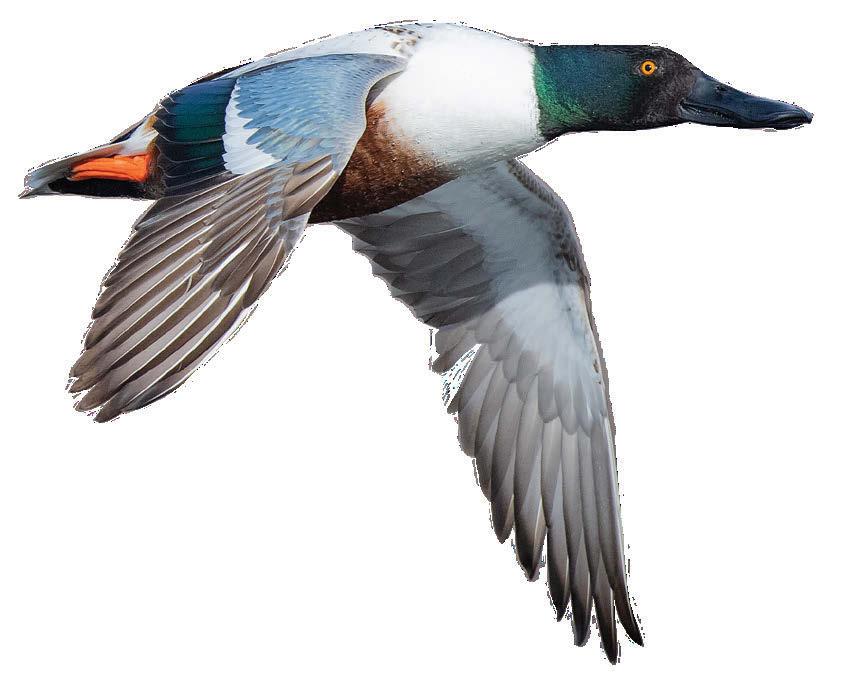

Look for these waterfowl (among the most readily identifiable and abundant winter guests at Barr Lake) feeding just off the shore, bobbing their heads in the water to fish out inverte brates, seeds, and plants. What to look for: The bird’s large bill (about 2.5 inches long) is shaped like a shovel. Males have bright white chests, rust-colored flanks, and green heads. Females and adolescent males are mottled brown and white.

File this objectively adorable bird under “intermediate to advanced identification,” as it camouflages itself against brown trees. But don’t fret if you miss it this month. The variety that visits Barr Lake spends summers in Colora do’s mountains, so they’re available year-round.

One year after CharlestheFirst’s death, Denver artists reflect on the ways the electronic musician continues to inspire them.

Charles Ingalls may have called California’s Truckee home, but the musician forged a lasting legacy in Denver. Going by the stage name CharlestheFirst, Ingalls special ized in electronic bass music, and his signature sound—low, throbbing frequencies interplayed with rich, ethereal melodies—could be heard during his frequent visits to perform at local venues big and small, from Cervantes’ Masterpiece Ballroom to Red Rocks Amphitheatre. In December 2021, Ingalls died during a tour stop in Nash ville, Tennessee, from what a coroner determined to be an accidental overdose of drugs that included fentanyl. Thousands amassed for Ingalls’ memorial concert at RiNo’s Mission Ballroom the following month, when a mural of him was unveiled. But perhaps a more telling tribute is the number of Colorado musicians and industry veterans who count CharlestheFirst among their most important influences. —CHRIS WALKER

I learn from his music all the time just by listening to it. He had such a unique way of creating his bass and drum sounds: They’re so bubbly and rounded. And his sound design work was both beautiful and powerful. We collabo rated in 2016 [on a remix, and later on “The Mist,” a single], and I’m grateful to have toured with him that year; he was always doing amazing things.

JOSH TEED Producer and instrumentalist

Charles’ music to me always will be the pinna cle of emotionality through bass music. More often than not, I feel that bass music is geared toward getting that crowd reaction and going hard. Charles’ music opened a lot of minds to a whole other aspect of creativity and expression within the genre. The way he was able to transport a listener to a different place will stick with me for life.

ORENDA DJ and producerWhen I first heard and saw Charles perform, in 2016 at a festival in California, I was blown away and knew that this was the kind of sound and story I wanted to tell through my own music. He proved that you could play soft, raw, and emotional music in a bass music set and it would be received well by even the biggest crowds. This is something no one really knew was possi ble. The sky was suddenly the limit for us all.

SCOTT MORRILL Owner of Cervantes

SCOTT MORRILL Owner of Cervantes

He was always lifting up his musician friends who were just getting started by mak ing sure they were included on lineups. One story his agent told me: [Ingalls] requested his name be smaller on a festival poster, because he wanted to be the same size as everyone else, which I have never heard of anyone doing. His music will live on forever, but I think perhaps the big gest impression he left on others was his kindness.

Self-care mecca Nurture offers a new way to indulge: dinner at Rewild.

Since it opened in 2020, Nur ture, a wellness marketplace, has enriched West Highland with a Pilates studio, acupuncture practitioners, and nutrition and counseling services. The heart of the 25,000-square-foot former elementary school, however, is its velvet-seat-lined cafe. During the day, the eatery is filled with natu ral light and goes by the name of Nest, but as of six months ago, the space has been transform ing into a moodier counterpart, called Rewild, at night. Guests still gather for gluten- and dairy-free breakfast and lunch fare, but the new suppertime concept—helmed by onetime Clayton Members Club chef Juan Tapia—delivers an afford able farm-to-table experience with hyperlocal ingredients from purveyors such as Tasty Acres, Rock River Bison, and Hazel Dell Mushrooms. This fall and winter, the menu is graced with dishes such as roasted delicata squash with muham mara, Camembert cheese, and crispy quinoa with walnuts and a bison burger topped with fennel-cranberry slaw, arugula, and mushroom gravy. Those hearty items are accompanied by organic wine and botanicinfused cocktails. The lineup is built for sharing, and the ambi ence—thanks to small tables, dim lighting, and cascading foliage— promotes intimate conversation, resulting in an eatery that nour ishes both the body and the soul.

—RIANE MENARDI MORRISONManna Restaurant has all the trappings of a buzzy hot spot: a locally sourced menu that changes with the seasons, an open kitchen, and dishes sporting spins on clas sics such as cilantro lime wings doused in black garlic and a jalapeño pickle pizza with fresh dill. The catch? The eatery is located inside Centura Castle Rock Adventist Hospital. “Oftentimes in hospital cafete rias, you see patients’ family members come down and look around at the stations, and they don’t know what to do or where to go,” says Adam Freisem, who was tapped to open the eatery with fellow chef Dan Skay in 2013. “That’s why we wanted to have a [true] restaurant. We wanted to be a place where people could get away from the clinical environment, sit down, and be taken care of.” The pair delivered, and the community responded: In fact, 90 percent of Manna’s diners now come from outside the hospital, even though it doesn’t have a liquor license. Prices are lower than those at area fast-casual restau rants ($4 to $16 for small plates and entrées), and there’s a heightened focus on nourishment through whole foods. In advance of the eat ery’s 10th anniversary, we sat down with Freisem to discuss what makes the restaurant destination-worthy. —BRITTANY

ANAS

ANAS

5280

Adam Freisem: Mostly our location. I can’t tell you how many times I get phone calls from people saying, I keep plug ging you into the GPS, and it drops me off at the parking lot of the hospital. The fact that we’re a nonprofit also makes us really unique. We’re not here for any other reason than to be a service to the community. We’re not here to turn a profit.

create?

One of the challenges we have is running a restaurant as well as patient room service. We operate hotel-style room service as opposed to the typical bulk cooking seen in a lot of hospitals. Our patients are our top priority, so adding the operations of the restaurant on top of it is always a balancing act.

You rotate your dishes regularly, but what items won’t your customers let you take off the menu?

The Fatted Calf is a halfpound, certified Angus burger we get from [Denver’s] Lom bardi Meats. We top it with caramelized onions, arugula, garlic aïoli, and a Port-Salut cheese. It’s a basic burger, but the cheese is melty like a raclette [dish] and has just a hint of funk. We also have a pizza called the Diamond Ridge. We do a fig jam on the base, with some beef prosciutto, and then we top it with Gorgonzola, moz zarella, and Parmesan. When it comes out of the oven, we give it a balsamic glaze.

How do you plan to keep Manna going for another decade?

Inflation and the cost of food have gotten insane. Our next menu will be more veggiecentric. You can treat a lot of veggies like a protein; I’ve done a cabbage steak dish before. We partner with Farm Box Foods in Sedalia and get these blue oyster mushrooms from them. Mushrooms are a beautiful substitute for meat products. You can treat them exactly like you would a steak. You can braise them, you can grill them, you can fry them. There’s definitely a demand for more plant-based meals, but from a restaurant perspective, it’s also more cost-effective.

: How is Manna different from other restaurants in Colorado?

Alcove Residences is located in the state of Colorado. All reservations, contracts and other documents relating to the sale of this real estate shall be executed only in the state of Colorado. No state bureau or division of real estate has inspected, examined, or qualified this offering. This advertisement does not constitute an offer or solicitation in any state where prior registration is required. All renderings and illustrative maps are conceptual only and subject to change. Amenities shown in renderings and illustrative maps are proposed, and may not occur. The developer reserves the right to make any modifications and changes as deemed necessary. Square-footages, dimensions, sizes, specifications, furnishings, layouts, and materials are approximate only and subject to change without notice. Window sizes, layouts, configurations and ceiling heights may vary from home to home. Prices are subject to change without notice. Errors & omissions excepted. Listing courtesy of Slifer Smith & Frampton Real Estate.

Colorado reminds Zin Zin Htun of Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), a country she left as a refugee. “I like it here a lot because my native town has a lot of mountains. [Colorado] feels like home,” says Htun, who arrived in Denver with her husband and two young children in 2015. Although she became accustomed to the West’s landscapes and traditions, she soon realized that many people aren’t familiar with her birthplace. “I tell people I’m from Burma, and they’re like, What is that?” she says. Those reactions fueled Htun’s desire to teach locals about her roots by posting cooking videos on YouTube that featured foods she ate growing up. In 2021, she opened her own catering

Htun imports whole green tea leaves from Myanmar and turns them into an earthy, tangy paste. After boiling and squeezing the excess liquid out of the leaves, she crushes them into a pulp using a mortar and pestle, adds minced garlic and lime juice, and lets the mixture ferment at room temperature for a few days. The dark green condiment is covered in vegetable oil and stored until ready to serve.

The chef shreds red and green cabbage and chops tomatoes and serrano peppers into bite-size pieces.

Big slices of toasted garlic deliver aromatic and sweet notes.

All of the elements are arranged separately in takeout boxes so everything stays fresh and crispy in

Htun urges customers to add the ac companying lime juice and fish sauce and then toss the salad with their hands, gently squeezing and dispersing the tea leaves with their fingers. This ensures every forkful is the ideal balance of salty, sour, spicy, and bitter—a trademark of her homeland’s cuisine.

The Cole neighborhood gets smacked by Brasserie Brixton’s refreshed bistro fare. BY

ALLYSON REEDY

ALLYSON REEDY

Brasserie Brixton doesn’t care what a French restaurant should be. It doesn’t mind that people have been conditioned to expect white tablecloths and a pretentious menu. Yes, Brixton often serves escargot and pâté—albeit with Ritz crackers sprinkled over those snails—but there’s also blood-sausagefilled wontons, Star Wars stormtroopers painted behind the bar, and hip-hop on the speakers.

To be honest, I think calling Brasserie Brixton a French restaurant is a stretch. I highly doubt, however, that a place folding blood sausage into wonton skins worries about what I think. So, if chef-partner Nicholas Dalton wants to bill it as such, then oui, French it is.

Classifications out of the way, what diners need to know about Brasserie Brixton is that it’s a very good restaurant where Denverites can enjoy smart dishes they won’t find anywhere else in town. That includes anchovy-saucelaced asparagus, a rotating beef tartare that riffs on everything from Arby’s Beef ’n Cheddar to a Thai-spicy crying tiger sauce, and inventive versions of the more typical French-ish suspects.

Dalton was inspired to break the mold with Brixton by his experiences at bistros in Montreal, where fine din ing chefs have swapped the pompous for the comfortable and are moving their opera tions from the city center to suburbs. “We wanted to cre ate something more casual, inviting, and fun,” says Dal ton, a California native. In short: No sky-high prices, no dress code, no fuss.

The menu here avoids norms, too. Instead of being divided up in the usual res taurant way between small plates and mains, everything is instead listed in one giant stack—but you can tell where the entrées begin as the prices rise. Among the

There are vacations and there are escapes. where a long weekend is nothing short of eternal.

more petite offerings, the asparagus is taut but yielding, like an angler’s pole when it has something on the line, and the stems are drizzled with miso bagna cauda, a garlic-andolive-oil sauce heavy with diced anchovies. The fishy flavor hits the palate hard, but combined with the freshness of the asparagus and the crispiness of toasted pine nuts, it’s a truly special bite. The baguette (sourced from RiNo’s Reunion Bread) with butter and the pâté— sweet, smooth, and white-portforward—are similarly enjoyable.

Where the dollar signs head north of $30, you’ll find the duck, which is served two ways: There’s the confit leg whose skin crackles when you bite into it and then the fried egg whose yolk oozes onto the turnip cake it sits atop. All of the components should be used to sop up the splatters of sweet ginger soy sauce and chile

may be off the menu when you get there: Brixton’s lineup changes often, and not just seasonally, but on a whim. “We’ll change dishes periodically,” Dalton says, “when ingredients and ideas come to us.”

Still, there are a few staples, and the cheeseburger is one. Most French eateries probably wouldn’t boast that their hamburgers are bestsellers, but Dalton wanted something approachable. The Brixton burger is a fancy take on In-N-Out Burger’s DoubleDouble, except it arrives with Gru yère cheese fused onto two thin, smashed patties that have the per fect griddle char. The melty-messy goodness is served with matchstick fries that are far superior to what you’d get at the drive-thru.

The short cocktail menu is remi niscent of the roster of food in that it mixes cuisines and ingredients in surprising ways—and downplays the whole, you know, French thing. My tasty X Marks the Spot was an almost tropical blend of apricot, pineapple, and cachaça garnished with mint. In the Pinky Promise, tequila, aquavit, and Aperol coex ist with salted watermelon in a sweetly delicious way. Sake (yes, the Japanese rice wine) is listed at the top of the menu, while the more French-centric grapes by the glass appear far below. “I love sake, and it pairs well with rich, fatty foods, which we lean toward with French cuisine,” Dalton says.

From a nautical-themed bar to a beloved taqueria, here are four other bars and restaurants to try in and around Denver’s Cole district. —AR

crunch. Clearly, this plate borrows flavors from the East, but I’ll con cede that its indulgence and preci sion feel decidedly à la française. The chicken is a rare miss; the smashed half bird was bland despite its ’nduja butter sauce and veggie accoutre ments. The version I tried, however,

What Dalton doesn’t lean into is the conventional French eating house ambience. The basic space, in the largely residential Cole neigh borhood northeast of downtown, is devoid of white tablecloths, yes, but it also lacks a cohesive vibe. Dal ton and his team set out to ditch the pretense surrounding French fare—so keeping the atmosphere simple and decidedly un-French was intentional, a part of their mas ter plan to redefine what we think about restaurants that serve pâté and escargot. The Brixton team is cooking the food they want to cook in an unintimidating space. It’s up to us to change our expectations.

Chef-restaurateur Henry Batiste serves Creole special ties his mom and grandma cooked during his child hood in New Orleans. That includes hearty gumbo, crispy catfish po’boys, and creamy red beans and rice—best washed down with a bottle of Abita, a Louisiana-brewed beer.

This establishment began as a food truck in the 1980s and is one of the original brick-and-mortar restaurants in the area. Inside, neighborhood dwellers have gathered for giant barbacoa gorditas, chicharrón tacos, and smothered burritos since 2002.

This petite watering hole, which opened in Cole last December, melds all the upsides of a divey hangout and a polished cocktail bar with a thoughtful natural wine list, cheap beer-and-shot specials, and a lineup of loaded hot dogs.

The seven bowls of noodle soup on deck—includ ing the indulgent, spicy lobster iteration—might be most tempting on a chilly winter night. But Cole residents know that the pork belly buns, poke, soba, and udon are just as tasty no matter what the thermometer says.

Under financial strain and a heavy mental load, ski patrollers are grinding to keep the slopes safe and make their profession more viable. We sent our writer to Eldora’s ski patrol tryouts to investigate what that looks like—and why skiers should care.

Nearly 20 skiers are squeezed into a hut atop Eldora Mountain on March 27, but only a handful know what’s going on as the radios begin to squawk. I’m one of 15 candidates in the room who are trying out to fill the four or so openings on the resort’s ski patrol, and we’ve been taking a break to warm up after an hour of ski drills on icy slopes. Now, we watch as our judges don helmets, pull on goggles, and rush out the door.

Zach Ryan, a patrol supervisor, stays behind with us and listens to the radio traffic. There’s a mechanical failure on the Indian Peaks lift, leaving hundreds of people stranded on chairs. Patrollers must close part of the mountain to ensure other guests don’t ski down to the malfunctioning lift until it’s fixed. While we wait for the tryout judges to return, Ryan fields our questions.

Most of the people in my group are vying to become full-time patrollers, others want to volunteer, and a few teenagers hope to ski their way onto the youth patrol, which would see them learn emergency first aid and assist in incidents to prepare them to join as adults. I’m here on assignment for 5280 to better understand what it takes to be a ski patroller in Colorado—and to see if I have the right stuff to put on the red-and-white jacket. But despite being a lifelong skier and a journalist who often covers the ski industry, I realize as Ryan answers our questions about wages, housing, medicine, and skier fatalities that I know almost nothing about the realities of his profession.

If I’m being honest, I also sometimes ski like an asshole. I’ve ducked ropes and run from patrollers. I’ve straight-lined groomers trying to set a new personal record for speed and weaved between beginners like they were racing gates. And I’ve always kept an eye out for patrollers, hoping to avoid a lecture from the fun police. Call it willful ignorance, but until today, it never occurred to me that the same patroller roping off terrain in the afternoon might have spent her morning responding to an uncon scious skier who hit a tree at full speed. I also never considered that she might go home to sleep on her buddy’s couch because she can’t afford housing—or that she might not sleep at all because she’s dealing with crippling stress from her chosen line of work.

After one morning on the mountain, I was only just beginning to realize how difficult the job could be.

WHEN THE JUDGES RETURN, they’re led by Neil Sullivan, Eldora’s assistant patrol director and the person facilitating the tryout. The 53-year-old is calm and affable, and if his heart rate has risen because of the Indian Peaks call, you’d never know it. He motions the candidates outside, addressing each of us by our first names as we clip back into our bindings. Then he tells us to ditch our poles. Earlier in the day, we’d done what felt like elementary drills—side-stepping down hill, then climbing back up in herringbone (reverse pizza) stances—but the tests help the judges evaluate our abilities to navigate the steep slopes and tight spaces required to access injured guests. (Eldora Ski Patrol used to recruit snowboarders, too, but skiing the mountain proved easier.) As Sullivan had told us earlier, carving turns is only a small part of the job. Now, though, those of us in my largely capable group have a chance to prove our true skiing abilities. We drop into a mogul run called Alpenhorn with instructions to ski fast and in control. Without poles, the judges

watch how well we square our shoulders to the mountain and manage our speeds—essential skills for running a toboggan. A couple of can didates drop in with swagger only to wash out. When we reach the bottom, I board the lift with Sullivan and ask about his approach to the tryouts. I’d heard other mountains give ski patrol candidates bib numbers and only learn their names if they score high enough. Why, then, does he take a more personal tack? “We’re pretty selective, too,” he tells me. “But we’re not just looking for good skiers. We’re looking for good people on top of those skis.”

In the 1990s, Sullivan tried out for another patrol he prefers not to name. “I remember thinking, It’s interesting they’re not talking to us,” he says. “They have 15 judges on the side of the trail, and they’re rank ing us.” Sullivan skied well enough that they learned his name, and he spent sev eral years patrolling at that resort. Now at Eldora, where he’s been for nine years, he’s found that creating a welcoming environment instead of a competition during tryouts is a good first step in building a cohesive group with high morale that wants to come back each season despite what he admits are paltry financial incentives.

LIKE MANY SKILLED WORKERS, ski patrol lers do a lot for a little. Sometimes they’re just pleading with out-of-control knuckle heads to slow the hell down. Other times they’re thinning out trees. But on many days, they’re using the professional training they’ve been given, including first-aid medicine and avalanche mitigation, to respond to skiers who need medevac flights and to bootpack explosives into avalanche zones. Historically, their pay has not been commensurate with those skills.

According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, professional patrollers in the United States earned an average wage of just over $13 per hour in spring 2021. The patrollers I spoke with told me starting pay in the Centennial State this past season was closer to $15 per hour, still barely enough to survive in most Colorado mountain towns. When Ryan, the patrol supervisor, started working at Eldora in 2016, he was a snow maker, but when he passed the ski test and was hired as a patroller, he started at $12 per hour, a $2-per-hour pay cut. It was worth it because he planned to go to medical school, and the experience would help him get there. (He enrolled this summer and is no longer

Cocktails

CANDY CANE FOREST

1 ½ oz. Candy Cane infused Breckenridge Vodka*

2 oz. white chocolate liqueur

2 dashes Bittercube Cherry Bark Vanilla Bitters Whipped cream

FIREPLACE TIPPLE

2 oz. Breckenridge Bourbon 1 oz. smoked grapefruit shrub* 1 oz. grapefruit juice ½ oz. lime juice 12 elderberries

Shake first three ingredients with ice. Strain and serve up. Top with whipped cream. GARNISH: mini candy canes

*Pour 8 oz. vodka and 4 oz. slightly broken candy canes into a mason jar. Seal, shake, and rest a few hours. Strain, return to mason jar, and refrigerate.

In a shaker tin, muddle elderberries. Add all other ingredients with ice. Shake and strain over ice. GARNISH: smoked sage, citrus and elderberries

*Over low heat, add 1 cup pink grapefruit juice, 6 oz. Turbinado sugar, and 2 oz. honey. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Turn off heat, let cool, and add 1 oz. grapefruit balsamic vinegar. Stir to incorporate. Add shrub into a sealable container. Smoke with a smoking gun or cylinder using applewood chips. Seal and refrigerate. **Smoking is optional.

WHISKEY MULLED WINE { batched , serves 6-7 guests }

6 oz. Breckenridge Spiced Whiskey 1 bottle Cabernet 1 oz. honey

1 oz. Turbinado sugar

1 tbsp. cardamom seeds, muddled

FIRST CHAIR

2 oz. Breckenridge Gin

1 oz. fresh lime juice

¾ oz. pine simple syrup* ½ oz. egg white

Top with sparkling soda

WINTER WONDERLAND

1 ½ oz. Breckenridge Pear Vodka 3 oz. pear juice

¾ oz. mace simple syrup*

1 oz. Breckenridge Spiced Rum 2 oz. cream liqueur 5 oz. Dark Roast Coffee

Over low-med heat, add all ingredients. Stir to incorporate. Continue to heat for 20 minutes. Then turn to low and cover for 30 minutes. Strain when you have the balance you like. Return to low heat and serve garnished with orange, cinnamon stick, star anise.

Dry shake first four ingredients (no ice). Shake again with ice and strain into glass. Top with sparkling soda.

GARNISH: pine sprig

*Over medium heat, add 1 cup water, 1 cup sugar and ¼ cup rinsed edible pine needles. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Let cool, strain, bottle and refrigerate

Shake all ingredients with ice. Strain and serve up.

*Over medium heat, add 1 cup water, 1 cup sugar, and ½ cup whole mace. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Let rest 20 minutes, cool, strain, bottle, and refrigerate.

Stir in all ingredients. Serve hot. Top with whipped cream.

GARNISH: pralines

an Eldora employee.) To be able to pay the bills, he spent his summers fighting fires in Montana and relied on hazard pay and over time to squirrel away enough cash to make it through each winter. It’s a balance that is more challenging than ever to maintain as housing costs in Colorado continue to soar.

Nowhere is this truer than in Breckenridge. With pay failing to keep up with the town’s high cost of living, patrollers at Breckenridge Ski Resort voted to unionize in 2021 and began

bargaining with Vail Resorts, which owns the mountain, to establish a new wage structure. In March, Vail Resorts finally announced a $21 hourly rate for entry-level ski patrollers at its 37 resorts—a higher wage than the union expected. While the increase was cheered across the industry, $21 per hour equates to about $41,000 a year. In Breckenridge, the average annual rent for a one-bedroom apart ment is $30,000, and that’s if you can find a unit that hasn’t been turned into a short-term

rental. “You could argue $21 an hour gives you a little more breathing room,” says Ryan Dineen, president of the Breckenridge Ski Patrol Union. “But if it’s impossible to move here unless you’re wealthy, we’ve eliminated so many people for whom this [profession] is not attainable or available.”

Still, Vail Resorts’ announcement could force other resorts to raise their wages to attract and, more importantly, retain patrol lers. There are encouraging signs: In 2022, Eldora and Copper Mountain, both owned by Powdr Corp., raised starting pay for patrol lers to $18 per hour. “For us to be able to get people to stick around for a couple of years, that’s been a challenge,” Sullivan says. “With all the effort that goes into the training, it’s disappointing if someone leaves after a year or two.” That high turnover makes it harder for patrol leaders to build reliable, experienced teams. In 2021, for instance, Eldora had to onboard nine patrollers, and because their first year on the mountain is essentially a

NOV. 18 APR. 9, 2023 18 de Noviembre al 9 de Abril de 2023

training course, more than half of Sullivan’s full-time team of 16 that season were learn ing on the job.

Larger resorts also struggle with reten tion. “Our patrol is younger now,” says Kara Flores, a supervisor at Winter Park. Flores has been patrolling for 16 years, and like so many of her colleagues, her love of skiing is what keeps her coming back. “You don’t do this for the money,” she says, but she recognizes that passion alone is no longer enough for many. “We used to have a ton of patrollers who’d been here for 30 years. Now, three to four years is average. With the cost of living being so high, it’s hard to keep people around because they don’t have a place to live.”

She hopes the job will become more viable as a career and not just as seasonal work, especially as pay increases and the advent of lift-served mountain bike parks help some patrollers keep their jobs year-round. But many resorts don’t have bike parks, and even if they do, there’s no guarantee they’ll pay the same in the summer as they do in winter, meaning most patrollers in Colorado are still on a seasonal grind. That financial stress only compounds the job’s mental toll.

“There used to be this misunderstanding that, as long as the powder was good, nothing we saw could actually hurt us,” says Laura

“They feel like they’re betraying their families for their jobs.”

Over 200,000 Denver-area children go to school hungry and it’s getting worse. Fill the Void: Amp the Cause to End Hunger is a program created to alleviate hunger through grocery gift cards. With your help we can Fill the Void created by overrun food banks, supplement SNAP benefit programs, and ensure children have reliable access to food. Your $250 donation will feed a family of four for two weeks.

Help end hunger by donating at fillthevoidcolorado.org

FILL THE VOID

Amp the Cause is a nonprofit that works with over 55 beneficiary organizations to improve the lives of Colorado’s children and families.

McGladrey, a psychiatric nurse practitioner at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medi cal Campus and a longtime patroller. “That was somewhat magical thinking.”

When skiers are critically injured on the mountain, those who respond often experience so-called stress injuries, which can mani fest as sleep loss, lack of motivation, anxiety, and depression. That’s why, several years ago, McGladrey created Responder Alliance, a program that helps outdoor professionals

by connecting them with each other and resources for psychological first aid and stress management. She created the program with techniques adapted from the United States Marine Corps and law enforcement, filling a gap in the outdoor emergency response field. “I saw some of the patrollers I worked with have career-ending stress injuries,” she says, “and I thought it was time to start adapting some of those tools.” Today, McGladrey vol unteers at Eldora as its stress and resilience

adviser. She trains patrollers to recognize stress injuries in themselves and others and helps them communicate about traumatic on-mountain events.

Over the past several years, Eldora, Vail Resorts, and others have also committed funding to help patrollers via counseling and other peer-supported initiatives. Many patrollers, however, still struggle to talk about their experiences. “It’s a lot more fun to tell someone on a chairlift I get to ski powder,” says Breckenridge’s Dineen. “[Not that] I did CPR on a dad while his daughter watched. People don’t want to hear those stories, and first responders don’t want to tell them.” When coupled with the economics of sea sonal work and mountain town life, stress injuries can make it difficult to justify staying on the mountain.

AS THE TRYOUT ENDS at Eldora, Sullivan lets the group know he’ll be in touch one way or the other. Then he quietly speaks with a few skiers, including me, to let us know we made it to the next round. Over the next several weeks, he will invite those who passed back to the mountain for a ride-along to see how well they mesh with the existing team.

Whether they stay on for multiple seasons, however, depends on how the profession con tinues to evolve. Powder laps and pro deals on new gear are great perks, but in the long term, they aren’t enough to overcome the “mountain tax,” the term for accepting lower pay to work in the outdoor industry than what you would receive doing a similar job elsewhere. Multiple patrollers told me that to stop the burnout—and the brain drain that comes with it—they need better access to affordable housing and health care, and they need some guarantee they won’t have to find a new gig every time the snow melts. “The future of this profession depends on retain ing experienced patrollers,” McGladrey says. “But many people who love patrolling have to leave it because they feel they’re betraying their families for their jobs.”

That’s bad news for Colorado’s skiers. As crowds have grown, Sullivan has seen skier speeds and poor behavior increase, too. “It’s what I call a reckless, out-of-control X Games mentality,” he says. Which made me think about my less-than-responsible behav ior over the years. Even though I didn’t end up joining Eldora’s team, I’ll slow down the next time I pass a patroller. And I’ll keep in mind what that white cross on their jackets really means. m

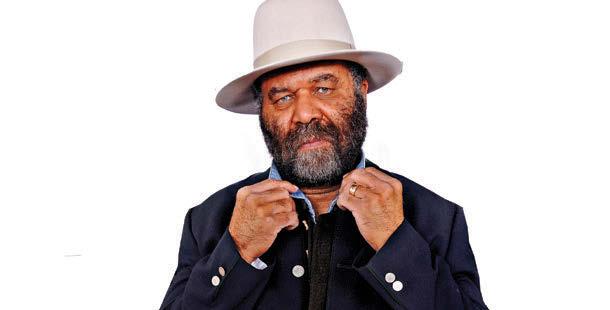

LAPOMPE Holiday Show Acoustic Christmas by El Javi

Around Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley, the legend is well-known: An eccentric old man living on Basalt Mountain had grown bananas at 7,200 feet. And from a patch of rocky hillside, perched precariously above a cliff, this gardening guru hadn’t only grown bananas; the lore suggested he’d brought to life all kinds of plants that seemed impossible to cultivate in the Rocky Moun tains, including guavas, papayas, dragon fruit, grapes, figs, and passion fruit. A quick scan of Jerome Osen towski’s property suggests the stories surrounding his high-elevation green thumb aren’t fables. “We have about 10 different citruses,” Osentowski tells me one afternoon, gesturing toward a cluster of bright green fruits emerging from a tree branch.

It’s a hot July day, and the short, bespectacled 81-year-old with unkempt gray hair is ambling along a wooden-plank pathway that bisects one of his greenhouses, which has been constructed—with the help of contractors and volunteers—with scrap material, giving the whole compound a DIY, dystopian feel. In fact, the property relies only on solar power, and Osen towski sometimes compares himself to a survivalist. “We’re

kind of the ultimate preppers here,” he says. “I look at this as a kind of ark—but Noah just had two of everything. We have 10 of everything.”

Osentowski is certainly right when it comes to plant life. Between his tropical- and Mediterranean-climate greenhouses and an outdoor food forest—where a cornucopia of fruit trees and herbs thrive—his property is a high-country Garden of Eden, teeming with so many plant species that his land may hold the largest diversity of edible species in all of Colorado. “Everything we have here has multiple yields,” Osentowski tells me. His eyes brighten while he demonstrates how one yield of a latticed vine is shading understory plants from direct sunlight. “And another of the yields is education,” he continues. “We have these plants here to teach people.”

Osentowski has done plenty of that educating himself, having overseen the longest-running permaculture design course in North America as part of the Central Rocky Mountain Per maculture Institute (CRMPI), a nonprofit he established in the early ’90s, with its headquarters on his property. Permaculture is a design discipline that can cover many different applica tions—not just gardening—but it generally aims to mimic

Jerome Osentowski is known the world over as a pioneer of permaculture. But can the Eagle County resident survive a challenge from a pest he never anticipated?

Affordable Certified-Organic in America. Urban Mattress.

nature, including replicating the kinds of diversity, resilience, and cross-species relationships found in self-sustaining environments. “We’re looking at native ecosystems and asking: How do they survive for millenniums?” he says as we walk past a pollinator garden buzzing with bees. “Every plant and every tree has a story.”

It’s obvious that Osentowski holds a special reverence for flora, and his connection to the world of roots, leaves, and seeds hasn’t just made him a local celebrity: He’s considered a pioneer of permaculture worldwide and has taught classes and presented at conferences in places like Nepal, Australia, Argen tina, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. But as beloved as Osentowski is by acolytes near and far, his adoration for plants usually exceeds his esteem for people. Halfway through my tour of his property, his cellphone rings.

“Excuse me,” Osentowski says, annoyed.

While he takes the call, I wander toward some cages that hold more than 70 rabbits— CRMPI’s main source of manure—but I can’t help but overhear Osentowski’s voice rising.

“No! No! NO!” he exclaims. “We don’t have any campfires here. That’s not a concern. I wish people wouldn’t go off the deep end and just talk to us!”

Even from a distance, I can tell Osen towski is venting about his neighbors, at least one of whom has lodged written

complaints with county officials about certain activities on his land. It’s one of the reasons I’ve made the trek from Denver to Osentowski’s property near Carbondale. This isn’t some minor quar rel between neighbors; complaints to Eagle County officials around issues such as traffic, construction permits, and perceived fire danger at CRMPI have drawn the attention of various government departments, and now the nonprofit’s future is in jeopardy due to a bureaucratic banality: zoning.

It’s a saga years in the making and has pitted the longtime plant whisperer against county land-use codes. After more than three decades of running CRMPI, the octogenarian stalwart who helped launch a global garden ing movement finds himself battling a tangle of fees and red tape that may be his and his beloved nonprofit’s undo ing. It also raises a slew of questions: What will become of Osentowski’s institute if the county moves against him? And what does the uncertainty around Osentowski’s property mean for his one-of-a-kind food forest—and his legacy?

Boulder Showrooms www.urbanmattress.com

JEROME OSENTOWSKI never planned to trans form one flank of a rocky hillside outside of Carbondale into a verdant paradise—much less one that’s become known around the world. By the time he pressed the first seeds into the nutrient-poor clay on Basalt Moun tain, he was already in his 30s, and his life had taken a number of unpredictable turns.

Born in 1941 on a farm in central Nebraska, Osentowski was one of five children in what was essentially a one-parent household where

the only language spoken was Polish. “We lived very close to the bone,” Osentowski wrote in a book he published in 2015 titled The Forest Garden Greenhouse. “My mother raised [us] on a hundred dollars of public assistance a month.”

The hard times instilled in Osentowski a sense of frugality, as well as a knack for selfpreservation and a desire for independence. At the age of 17, he left home and signed up for the U.S. Air Force, first playing drums in

the Air Force band in Denver, then serving in administrative roles in England and Ger many during the Cold War. Paper-pushing didn’t suit him, though, so Osentowski’s gaze eventually turned stateside, where he returned to attend Orange Coast College and then San Diego State University in California on the GI Bill. Officially, his focus of study was political science, but it was Lee Canyon ski resort in Nevada that drew more and more of Osentowski’s attention; after a few winters, he became a full-time ski instructor.

Like any skiing careerist, Osentowski quickly found himself lured by the dry powder and black diamond descents of Colorado’s slopes. In 1969, he moved to the Aspen area to work winters as a ski instructor and summers as a carpenter. He even taught Hunter S. Thompson how to ski. (“He didn’t have any ether with him,” Osentowski jokes about the lesson. “But all the other drugs were there.”)

It was around this time, in 1975, that Osentowski saw an ad for land for sale on Basalt Mountain. It was the cheapest prop erty he’d seen available in the Roaring Fork Valley—$13,000 for nine acres—but most important, it fulfilled the one requirement Osentowski was looking for: a secluded spot to build the proverbial cabin in the woods. At the time, the 34-year-old didn’t know much about gardening and nothing about perma culture, but he planted a few root vegetables anyway. His first attempts failed miserably.

It wasn’t until years later, when he crossed paths with a permaculture designer named Michael Winger at the Aspen Commu nity School, that Osentowski would begin to unlock many of the discipline’s secrets— such as enriching soils in raised beds and planting species that work symbiotically with each other—that would enable edible plants to flourish on Basalt Mountain. The concepts fascinated Osentowski enough that he signed up for courses with Bill Mollison, who, along with David Holmgren, coined the term “permaculture” in the ’70s. The two Australians rejected modern industrial con cepts such as constant growth and reliance on nonrenewable resources. Much of what they espoused had been practiced by vari ous Indigenous peoples for millennia. But Mollison and Holmgren’s practical design applications—including greenhouses—as well as their writings on the topic inspired farmers to pick up the practice.

Inspired by the nascent movement, Osen towski decided he’d give gardening on Basalt Mountain another try. He even constructed a 60-foot-by-22-foot greenhouse and named it Pele, after the Hawaiian goddess of fire,

who he hoped would keep his plants warm. In Pele, Osentowski also engineered a prototype of something for which he’d later become famous: a so-called climate battery. Basically, the device consists of an underground sys tem of plastic tubes connected to fans that suck the hot, moist air from the greenhouse atmosphere and distribute it beneath the soil. Thanks to this innovation and others, the plants thrived, and Osentowski’s timing was such that he became a central player in a mixed green salad revolution.

In the 1980s, Osentowski says Aspen restaurateurs were trying to transform Ameri cans’ understanding of salad away from a sad standard. “They were just eating ranch dressing and iceberg lettuce,” he says. So as he began producing mixed greens such as Swiss chard, kale, and arugula, his roster of restaurant and grocery accounts swelled to 18; for many years, he was making $1,500 a week selling mixed greens to area businesses.

Word about Osentowski’s successes with permaculture spread around the Roaring Fork Valley—and then outside of it. The more people heard about it, the more they asked if they could come learn. The demand to understand the gardening guru’s floral for mulas inspired Osentowski to begin teaching classes in 1987 and ultimately offer his now well-known permaculture design course, which covers topics such as soil building, greenhouse maintenance, and water-capture technologies.

Osentowski’s longtime friend Michael Thompson took the course himself and mar veled at Osentowski’s abilities with plant life. As a trained architect, however, Thompson couldn’t help but notice that Osentowski’s greenhouse “looked like it was built with baling wire and bubble gum.” Still, he was impressed by Osentowski’s innovations, including the subterranean air system. The architect eventually entered into a greenhouse design business partnership with Osentowski called Eco Systems Design; it was Thomp son who coined the term “climate battery.” Over the past 21 years, they’ve given back to the community by helping design gardens and greenhouses at roughly 60 percent of the schools in the Roaring Fork Valley and have taken on more than a hundred com mercial greenhouse projects in Colorado and around the world.

But life at CRMPI has not always been rosy. At around 3 a.m. one night in October 2007, Osentowski woke up to the smell of smoke and found flames erupting out of the top of his beloved greenhouse. By the time firefighters made it to his property, Pele was in ruins. “It was said to have started in the flue of the sauna,” Osentowski says of the

fire, referring to a wood-burning sauna he’d attached to one end of the greenhouse. “But I think it could have been arson. People have been trying to get rid of me for a long time.”

BASALT MOUNTAIN HAS LONG BEEN a place where people come to seek peace and quiet, as Osentowski originally did himself. But over the years, the institute has drawn several thousand people to its greenhouses and edible food forest, many of whom have camped on the property in order to spend more time learning on-site from the man who can grow almost anything at elevation. It’s the comings and goings of the permaculture-curious on the area’s main road—a winding, treacher ous drive with heart-pounding drop-offs and few places to pass vehicles—that have sometimes led to altercations.

Osentowski says he’s tried to make nice with his neighbors—inviting them for tours of his land, giving them fresh produce—but anyone who’s spent enough time with him knows that Colorado’s godfather of per maculture can come off as prickly. Some of Osentowski’s students and volunteers halfjokingly refer to him as a thistle: He’s resilient and hardy, as evidenced by how he replaced Pele with a better greenhouse after the fire, but he can sometimes poke or sting with his words. In 2018, one neighbor felt she’d been pricked enough by CRMPI’s existence that she filed a written complaint with Eagle County administrators.

The complaint, which referenced possible nonpermitted construction activities, put CRMPI on the radar of Eagle County’s planning department; its property inspectors subsequently found a litany of issues. As Thompson puts it, when Osentowski built most of the structures on his property and established CRMPI, “it never even crossed his mind that he should be looking at the Eagle County land-use code.”

Osentowski says he has since spent more than $250,000 on new construction, engi neers, and consultants to get his property up to code—including doing electrical work and improving emergency evacuation routes in case of a fire. The most frustrating expense of all, though—and the biggest insult to Osen towski—has been having to justify the very existence of CRMPI within Eagle County’s zoning code. Because CRMPI teaches classes and hosts a campground in a residentially zoned area, Eagle County officials told Osentowski he needed to apply for a special-use permit if he wanted to continue those activities. As guidance, the planning department recom mended he apply for a resort recreational facility permit, because it was the closest

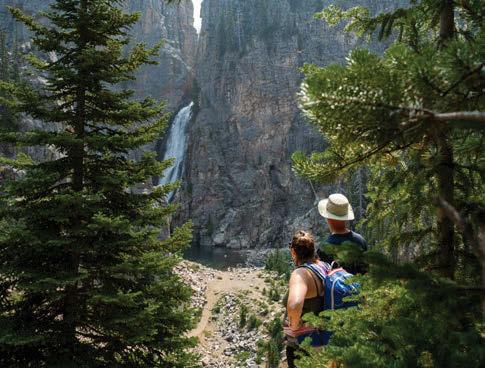

The world comes out west expecting to see cowboys driving horses through the streets of downtown; pronghorn butting heads on windswept bluffs; clouds encircling the towering pinnacles of the Cloud Peak Wilderness; and endless expanses of wild, open country. These are some of the fibers that have been stitched together over time to create the patchwork quilt of Sheridan County’s identity, each part and parcel to the Wyoming experience. Toss in a historic downtown district, with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a vibrant art scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; small town charm from one historic outpost to the next; and living history on every corner, and you have a golden ticket to the adventure of a lifetime.

classification they could find in their zon ing code. Osentowski begrudgingly hired a consultant to prepare the application.

After years of delays due to the pandemic and county staffing issues, he finally got a chance to make his case to the Roaring Fork Valley Regional Planning Commission on July 21. Before a packed room in the Eagle County Courthouse in El Jebel, a consul tant named Maya Ward-Karet explained how CRMPI had accommodated every county

request it could and laid out a plan for how CRMPI would prohibit campfires, import port-a-potties, and use shuttle buses to reduce vehicle traffic.

Before the commissioners made a decision, they opened the floor to public comment, and a rather remarkable scene unfolded. Over three hours, dozens of community members spoke in favor of CRMPI, includ ing former Aspen Mayor Bill Serling. They provided various reasons for why CRMPI

should be allowed to operate. “This is about preserving a legacy in our valley, a jewel rooted literally—pun intended—in Basalt Mountain,” said Doug Graybeal, an area resident. Eagle County local Richard Blair concurred, adding, “With all due respect to the other homeowners, but with just a little change in perspective, living in such close proximity to an international legend could be an asset. It could be something that they could be excited about.”

Some commenters asked the planning commission to be less rigid with its zoning code. Even Bob Schultz, a former volunteer member of the commission, pointed out that, in the past, neighboring Pitkin County had been amenable to allowing two farming- and climate-focused nonprofits in its municipality to operate in ways—including creating heavy traffic—and in residential areas that conflicted with rules in the zoning code. “[Pitkin] went through [a process] to try to straighten out some irregularities over there because everyone agreed [those nonprofits] were important things to keep in our community,” Schultz said. “I would ask you to actually consider that rather than a strict interpretation…because Jerome and CRMPI have been a net positive to the Roaring Fork Valley.”

Others focused specifically on climate change and explained how, in these tenuous times, humanity needs more sustainable, zerowaste farms like Osentowski’s. One speaker even referenced This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, a book by Naomi Klein. “[Klein] points out how bureaucracy and its red tape is the reason why our global crisis of climate change is such an issue,” the woman told the commission. “Are you here to help our community? Or are you here to hinder our community?”

We’ve been in the dream-making business since 1973.

As dusk fell, the wave of support swelled on, backed by more than 100 letters submitted championing CRMPI. In the end, the plan ning and zoning commission was not swayed. By a 4-1 vote, the commissioners denied the application, citing inadequate road access and evacuation plans, as well as general incompat ibility with the surrounding neighborhood.

ccu.org | 303.978.2274

Osentowski hung his head. While the July 21 vote was only a recommendation, he’d just lost a major battle, and it was all but certain how the county’s commissioners would rule on that recommendation a couple of months later. Being denied a special-use permit would mean he could no longer teach in-person classes on his property—his finan cial lifeblood—or host volunteers on-site. Any retirement plans he once had, includ ing living in the tropics for half of the year, would have to be put on hold. By the time

the county commissioner meeting arrived on October 17, he’d prepared for the worst. He listened while officials, aggrieved neigh bors, and permaculture allies all argued the finer points of CRMPI’s special-use permit. Almost three hours into the proceedings, the county commissioners broke for an execu tive session. When they returned to the dais, something unexpected happened.

“I think CRMPI clearly provides a public benefit to residents and visitors,” said Eagle County Commissioner Kathy Chandler-Henry. “We have grave concerns about climate, the heating up of the planet, and the food inse curity around the world. And I think that this is a benefit not only to Eagle County, but to a much broader region.”

With that, the three commissioners said they were prepared to approve CRMPI’s application if Osentowski agreed to meet 18 separate conditions, including improving evacuation routes and prohibiting camp fires on his property. Finally, it seemed Osentowski’s bureaucratic woes were nearly over. But always the thistle, there was one condition the permaculture guru would not agree to: that the permit be tied to his ownership of the property.

“Part of permaculture is being able to turn [things] over to the next generation,” he told the commissioners. “The education continues beyond me.” The commissioners, clearly not expecting an 11th hour request to extend the permit beyond Osentowski’s stewardship of CRMPI, said they couldn’t trust that a future owner would honor their conditions, and tabled the vote until a ten tative date of November 30. (Eagle County declined to comment until after the county commissioners have voted.)

To many, Osentowski’s move will come across as risky—and possibly boneheaded. But he told me that he views this permit application as his one shot to ensure CRMPI endures over time. While he could start the whole bureaucratic process over, retooling a special-use permit application under a dif ferent designation, he’s not sure he has the heart, the cash, or the strength to pursue that at his advanced age. And the meetings haven’t been all bad. “I felt validated that my life’s work was appreciated,” he says. At the same time, Osentowski’s future—and the future of his food forest—remains blurry. Until the final vote, all he can do is stay grounded in what’s always spoken to him: his plants. “The land knows you,” he says, “even if you’re lost.” m

Alien Throne Visit FarmingtonNM.org today and awake your thirst for adventure.

The CSKT Bison Range, managed by the Confederated Séliš and Ksanka Tribes, covers more than 18,500 acres in Montana.

The CSKT Bison Range, managed by the Confederated Séliš and Ksanka Tribes, covers more than 18,500 acres in Montana.

For the nomadic community, home is where you park it, and over four days in June, that was the tiny hamlet of Hudson for more than 120 camper vehicles. Souped-up custom vans, vintage Volkswagen buses with pop-up tents, and skoolies (converted school buses) descended on the mountain-nestled Wind River Country for the inaugural Wind River Rally. The gathering—which featured live music, gear swaps, perfor mances by a traveling circus family, morning yoga sessions, and fresh ink from mobile tattoo artist Chris Montes—is slated to return in August. That’s good news for van lifers and overlanding enthusiasts and even better news for area businesses such as Svilar’s Bar & Steakhouse and Wyoming Whiskey. Local outfitters also got an economic boost by host ing add-on adventures like hot air balloon rides, guided rock climbing, bighorn sheep viewing, and historical mine tours. —Karyna Balch

About 2.5 miles from the extravagance of the Las Vegas Strip sits chef Natalie Young’s breakfast and lunch joint, Eat. Like its no-frills name, the restaurant’s menu is light on adjec tives, with options such as “shrimp and grits” and “chicken salad.” But sample the homemade sourdough bread and aged cheddar that make up the grilled cheese or the Parmesan-rindinfused tomato soup and you’ll taste their creator’s dedication to fine-cooking techniques. “I keep it simple and approach able,” says 59-year-old Young, who was trained by a classical French chef at the Paris Las Vegas casino. Her food’s subtle depth is a big part of the reason why the restaurant is celebrat ing its 10th anniversary this year—an extraordinary tenure for a low-key, alcohol- and smoke-free eatery in a town full of glitzy, celebrity-chef dining destinations. Young says she still feels gratitude for each pancake- and Reuben-ordering patron: “Every person that makes their way over to my little restaurant makes me feel blessed.” —Courtney Holden

When Heidi Rentz Ault and Zander Ault first visited Pata gonia, a small town 18 miles north of the Mexico border, in 2015, they quickly real ized they’d stumbled onto a gravel biking paradise. The then nascent cycling discipline steers riders off pavement and onto wider, less obstacle-laden trails than mountain biking singletrack, and the couple has since tapped into the fastgrowing sport via a variety of ventures. In Patagonia, they hold gravel camps through their guide company, the

Cyclist’s Menu; they launched the annual Spirit World 100 ride in 2019; they run Patago nia Lumber Company, a cafe and bar; and they converted two homes into Instagramworthy Airbnb destinations in 2020. Their two-wheeled empire is built on the San Rafael Valley’s 100-plus miles of gravel roads, which wind between the Santa Rita and Huachuca mountain ranges that rise dramatically from the desert floor. In early 2023, the duo plan to expand their lodging offerings, all under the Gravel House moniker, to include a nine-room hotel in town—meaning even more people will be able to discover this gravel riding mecca. —JL

90°, 180°, City); Eric Piasecki/© Michael Heizer/Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation (City, 1970–2022); Courtesy of Tandem BASE

Area 51 isn’t the only mysteri ous locale tucked away in the Nevada desert. For more than 50 years, large-scale sculpture artist Michael Heizer has been building “City,” a mile-and-ahalf-long installation within Basin and Range National Monument composed of dirt, rock, and concrete. The project, which opened to the public in September, is reminiscent of ancient ruins while simultaneously evoking a futuristic metropolis. Actually seeing Heizer’s monumental work might be as difficult as spotting a UFO, though: Only six people (who are picked up in the nearby town of Alamo, nearly 100 miles north of Las Vegas) are allowed to visit each day. Heizer, 78, hopes the exclusivity will allow viewers to be fully immersed in the structure’s eerie geometry and shifting shadows instead of theme-park-esque crowds. Booking for 2022 has already closed, but the Triple Aught Foundation, which manages “City,” will resume accepting reservations ($150 per person) for 2023 in January. —Barbara Urzua