ISSUE 2

SPRING 2017

ISSUE 2

SPRING 2017

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Nonfiction Editor

Comics Editor

Fiction Editor

Poetry Editor

Web Editor

Social Media Manager

Zoë Bossiere

Dakota Clement

Karie Fugett

Julia Malye

Sarah Kosch

Robin Cedar

Joe Donovan

Robin Cedar

Readers

Chessie Alberti

Colleen Boardman

Mohana Das

Sheila Dong

Joe Donovan

Paisley Green

Taylor Grieshober

Jessie Heine

Kristy Hae Su Joe

Kay Keegan

Addison Koneval

Ryan Lackey

Randy Magnuson

Sam Mitchell

TJ Neathery

Linnea Nelson

Jenna Noska

Kayla Pearce

Ben Sandman

Jess Silbaugh-Cowdin

Ben Swimm

Holly Taylor

Natalie Villacorta

Andrew Zingg

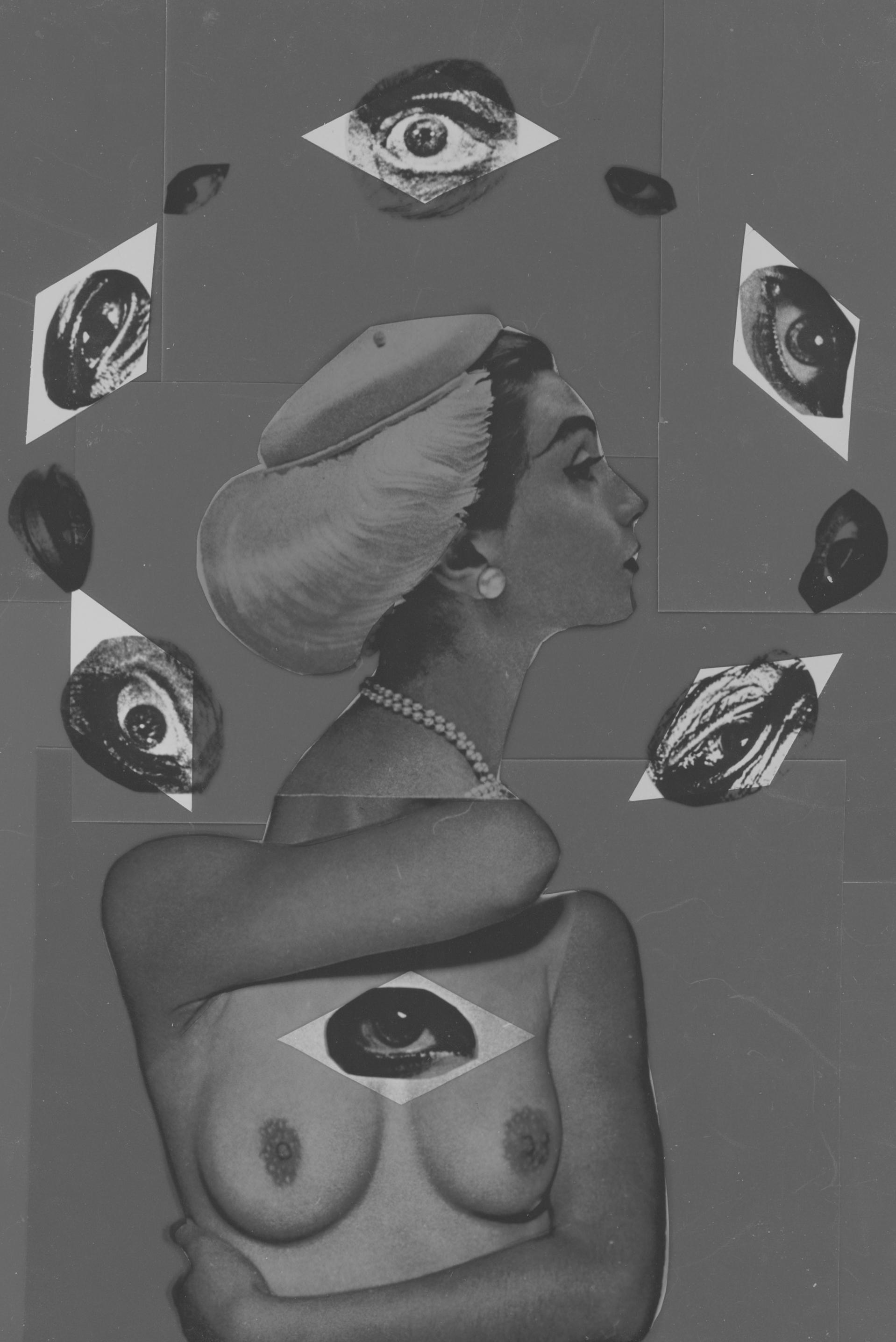

Cover & Insert Art by Micah Mermilliod

“Color Theory #1 (Communication)“ 2017

“Color Theory #4 (Connection)” 2017

“Color Theory #5 (Observation)” 2017

www.45thparallelmag.com

Copyright © 2017 45th Parallel

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This year, at the AWP conference in Washington D.C., I did a good amount of promotional work, spreading the reach of our fledgling magazine to other editors of other magazines, hoping to establish a few lasting connections. On this expedition, I encountered more than one writer who would nod in recognition when I introduced myself as our Editor-in-Chief. “Oh, you’re with 45 th Parallel?” they’d ask, shaking my hand. “Haven’t I heard that name somewhere before?” To my surprise, this happened again and again.

What a testament to the strength of our first issue that we’re already on the radar of so many writers looking to submit their work! I can recall the uncertainty of only two years ago, when we had no issue, no money, and only our own determination to guide us. As the magazine’s second ever Editor-in-Chief, I felt a tremendous pressure not only to curate a second issue as strong as the first, but also to keep the magazine alive in its most vulnerable early stages. I’m relieved and pleased to say that 45 th Parallel’s second year was a huge success, an emphatic reassurance that Oregon State’s literary magazine is here and here to stay.

Because of our rotating staff as a two-year MFA program, 45 th Parallel is by necessity a magazine whose aesthetic is always in flux. Each year, our editors write a short description of what they’d like to see published in the next issue. Though this year our call for submissions didn’t specifically ask for themed work, we received (inevitably, I think) an overwhelming number of political submissions across genres, many of which made it into these pages. I’ve heard it said a lot recently that to write is a political act. We at 45 th Parallel believe publishing is also political, and we are always committed to publishing work from a diverse range of perspectives. In this issue, you’ll find our writers grappling with issues of identity, race, religion, sex and sexuality, and feminism in uncertain times. We are proud to represent these voices, and it is our hope that these works will surprise you, teach you, and leave you inspired.

I’m so proud of all we have achieved in only two short years. I want to thank our readers for their critical eyes and thoughtful perspectives, our editors for their dedication and verve. Thank you especially to our Faculty Advisor, Justin St. Germain, for his continued advocacy and support of 45 th Parallel’s vision.

It is a real joy to have been a part of 45 th Parallel’s early years, and a comfort to know the future of the magazine will be left to capable hands. I sincerely hope you enjoy our second issue of 45 th Parallel magazine, and stay tuned for the many more to come.

With affection,

Zoë Bossiere, Editor-in-Chief

Editor’s Note

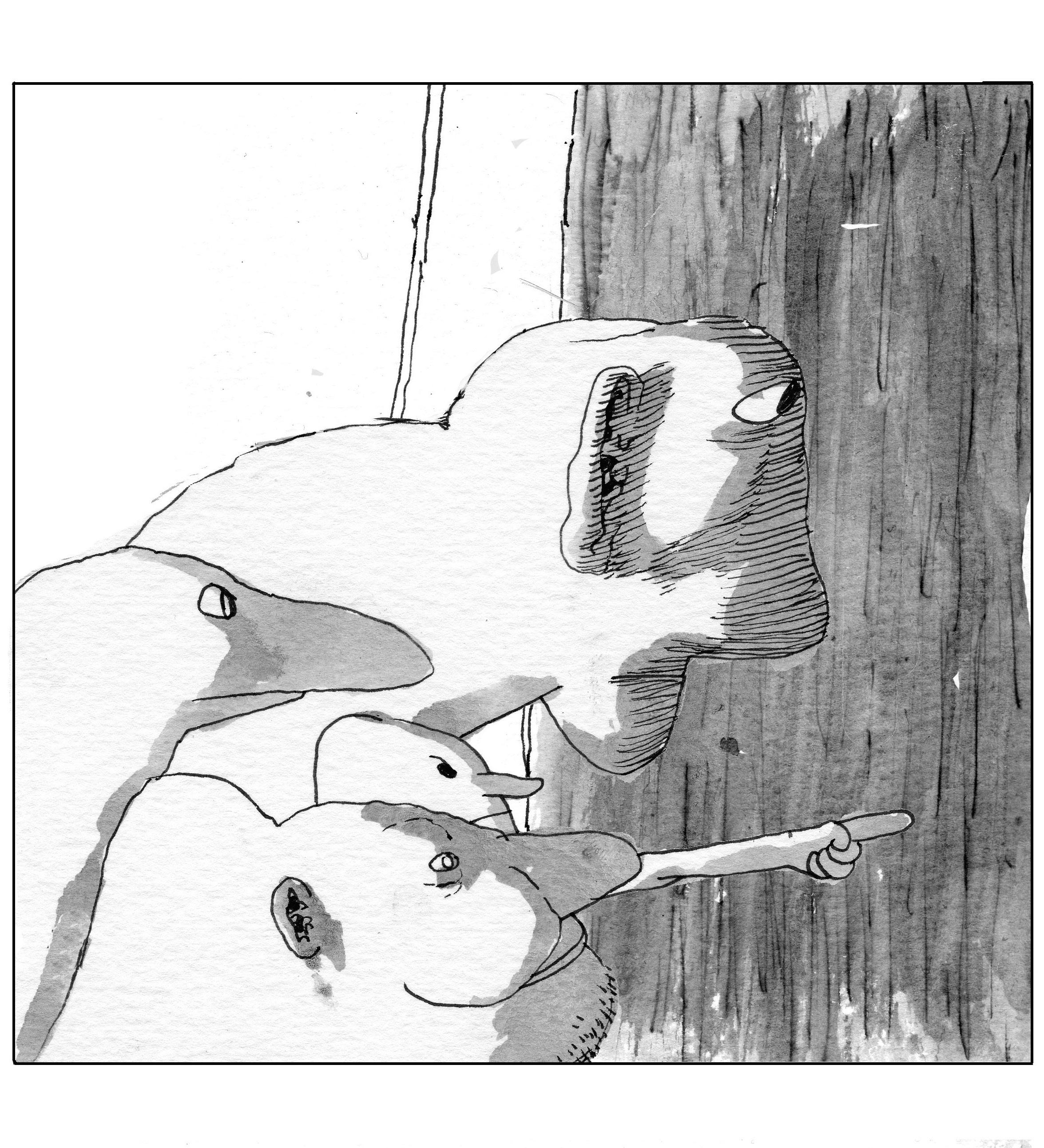

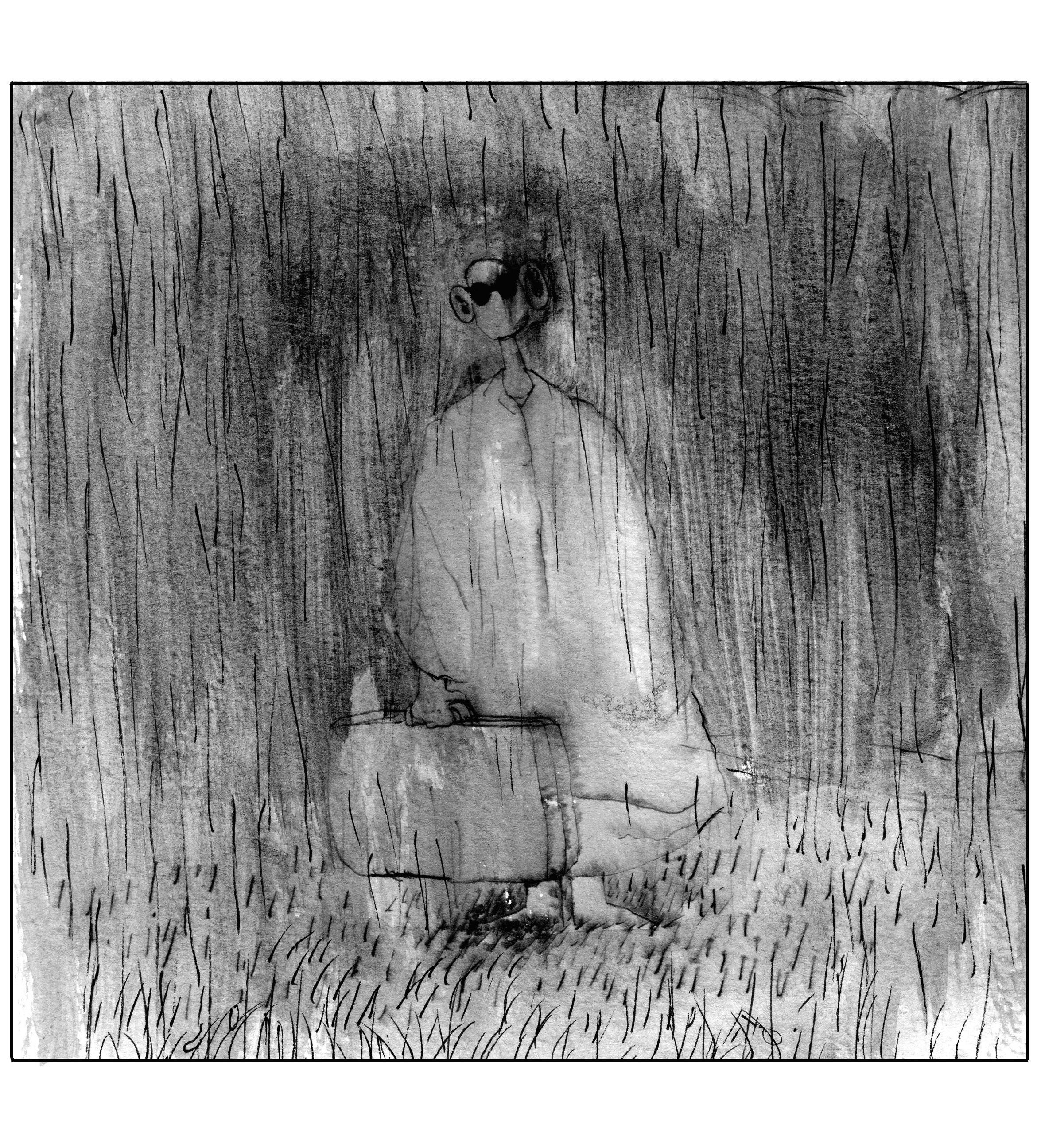

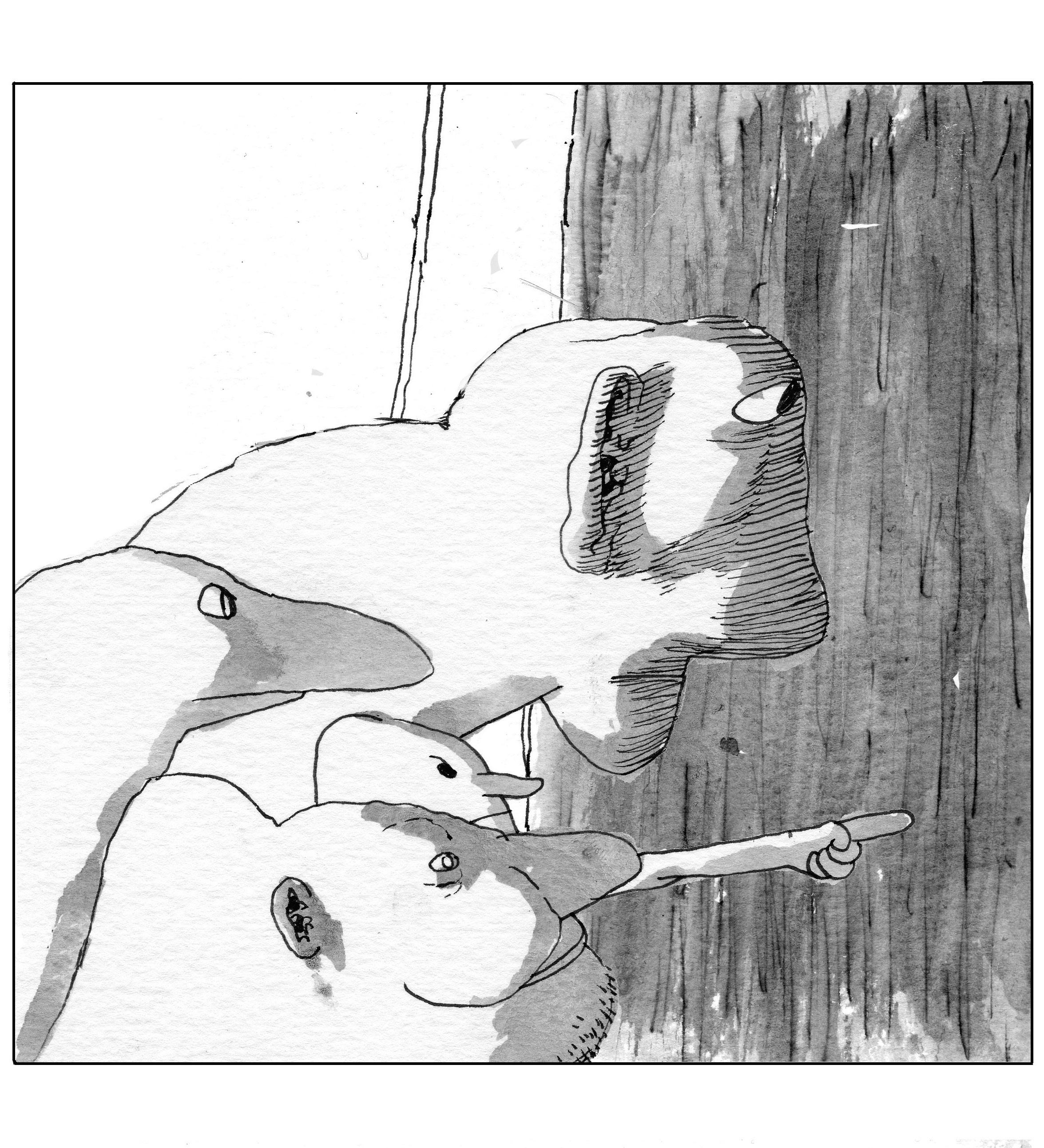

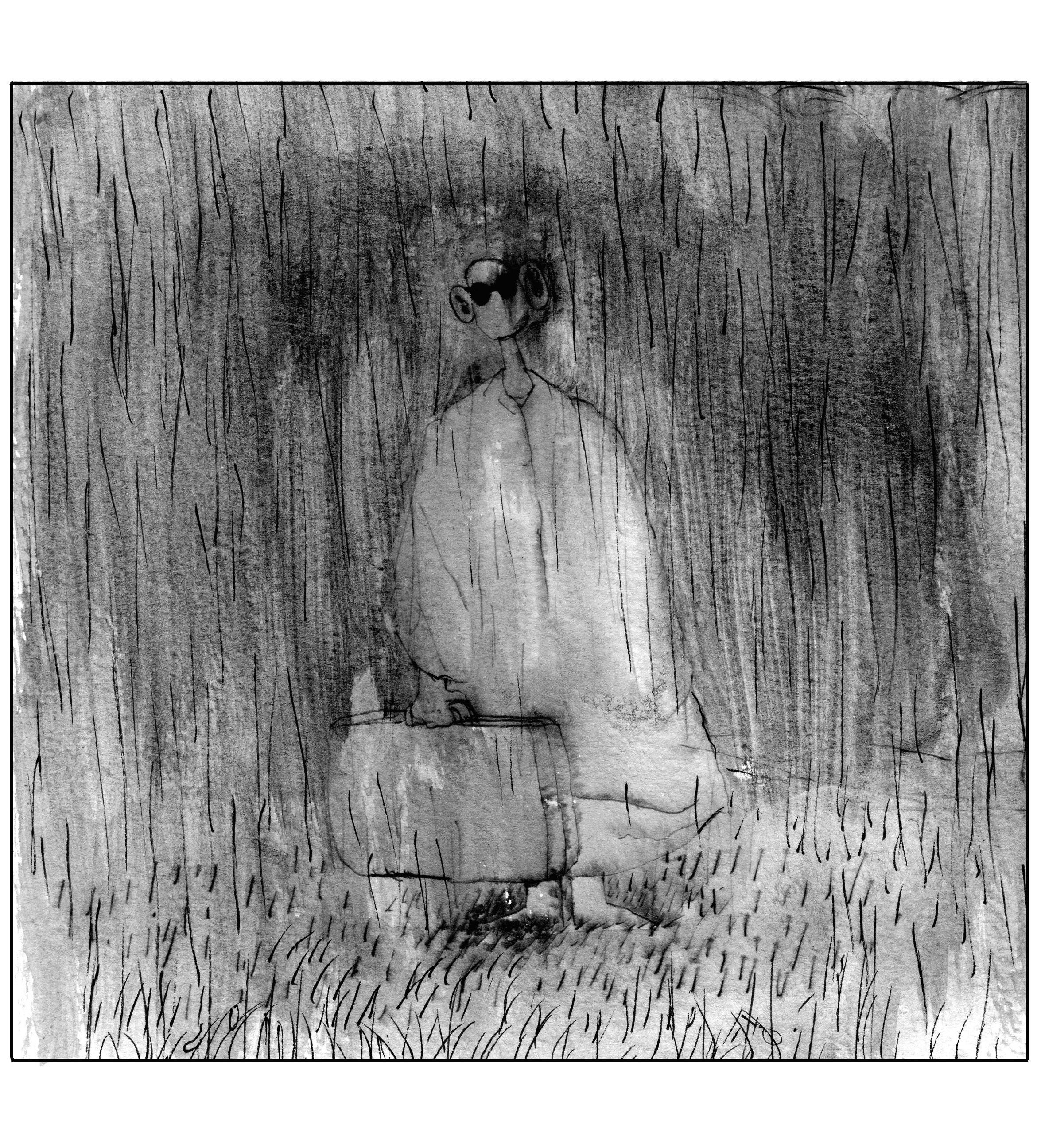

CONTENTS Poetry Katherine LaRue Right Atrium 1 Jory Mickelson Cloud 4 Kimberly Grabowski Staryer I wanted the gun in my mouth 5 Cheyenne Black Ten is Too Girl 11 Bonnie Arning Gathering Evidence 14 And all the papers read... 16 Kathryn Merwin Necromancer 26 Amanda Stovicek Drawing Death 27 John Paul Davis Fuel 32 Sasha West The List of Broken Things 33 Husbands are Deadlier Than Terrorists 34 F. Daniel Rzcinek Leafmold 43 Gail Langstroth Ultraviolence 49 Rebecca Givens Rolland Blazoning Leaves 59 Nicholas Brown Mom’s Still Afraid 60 Emma Bolden The Gods Have a Bullet 70 The First Time After Surgery 71 Fiction Robert Fromberg River 6 Mark Hodge Grandpa and the Duke 18 Corey Farrenkopf You in Another Body 30 Hannah Gilham Bobby 36 Jeff Ewing The Insurrection at Fort Bob Ross 44 Commute 45 Kent Kosack Misanthropy LLC 50 Rick Krizman A Field Guide to Billionaires 68 Nonfiction Crystal J. Zanders Everyday Racism 2 Rachael Peckham Lift 12 Krys Malcolm Belc The Broad Street Line 40 Your Father, The Cab Driver 42 Shaun Anderson Write the Scene 46 Jackie Huertaz Public Notice 56 Emely Rodriguez Reflections 62 Comics & Art Joel Orloff The Stranger 28

Katherine LaRue

Katherine LaRue

Right Atrium

You called for me so I went across the red bridge. Girls gripped the railing, dresses caught by the wind. Girls took pictures on their phones. Maybe their lips were red. Between the white streams of traffic animals were crushed, unidentifiable. Underneath the boats unzipped the river in the dark.

Nosebleed after nosebleed, we sat in your expensive bed, garnets distilling in the neat cube of my palm. If my thumbs were cold you blew on them, epic-eyed. You draped your jacket over me and it said there there.

I came over, but I shouldn’t have brought my body. You left it more or less a pendulum. Twine tied around a stone very badly, filled with your mean vowels. Every anatomy is eventually faulty. A dumb pile of rope and boulders.

45th Parallel 1

Crystal J. Zanders

Everyday Racism

Ms. Alma, my grandfather’s mother-in-law, at 95 is the oldest black person I’ve ever known. She didn’t have much formal education, so when she was my age, she kept the kids and the house for a rich white family.

When I was in the 8th grade, they decided to build a park next to our school. They took a survey to see whether we would prefer a skate park or basketball courts. The basketball courts won, but they built a skate park anyway. They didn’t want to attract the wrong element. I knew that we, the black kids, were the wrong element.

My white ex-husband told me that black people treated him differently when they found out he was married to a black woman. He became “honorarily black.” I think it only went one way.

My grandfather was walking down the street when a white recruiter shouted, “I bet a nigger can’t pass this test.” He stopped, took the test, and signed at the bottom “so it could be graded.” The recruiter welcomed him to the U.S. Army, where he served 20 years. He did three tours in Vietnam.

I told my mom that I hated high school because I felt like I had to work so much harder than everybody else to get the same thing. Years later she told me that I had.

When I taught alternative school, at the beginning of every year I had to explain that “Profanity is not allowed” included the “n-word.” Every year someone would say, “Why can’t we say nigger? We’re all black.”

My friend and I tried to see a play in Mississippi. Most of the seats were pre-sold, but the lady told us that if we waited, we might be able to get seats. We waited over an hour, but the same lady gave the last two seats to the older white women who came in after us.

In college, I went to talk to the head of the Honors Program. Because I had an African American scholarship, I wasn’t forced to participate like most of the other students. He tried to talk me out of it, as if I didn’t belong there. I wanted to belong there; I wanted to be an honors student. There were over a hundred students in that class. I was the only black student.

In Mississippi, a white kid has to set something on fire to be sent to alternative school. A black kid can get too many tardies.

45th Parallel 2

I went car shopping with my brother. At the second dealership, a white man asked to run my credit before he would show me a car in my price range. I asked him why, and he said he wanted to know if I could pay for the car. I left.

When I look up my former students, several are incarcerated at Parchman Prison. Most of them committed crimes as juveniles. It is expensive to imprison a juvenile, so their cases are postponed until weeks before their 18th birthdays.

I quit my grad school babysitting job when they asked me to clean the bookshelf. I was already washing the dishes and vacuuming and straightening the playroom on my oncea-week visits. That bookshelf hadn’t been cleaned by anyone since I got there. I felt like Ms. Alma, keeping kids and cleaning house for a rich white family.

I read that black preschoolers are expelled at higher rates than white preschoolers. Do they hate our babies, too?

My mom made me go back to the dealership and talk to his boss. I told the man my story and he apologized profusely. He told me that if I still wanted to see a car, he’d be happy to make me a deal on anything on the lot. I told him that I was going to buy a car with the folks who treated me right the first time. The next time I went car shopping, five years later and a thousand miles away, it happened again.

The state of Mississippi’s convict leasing program was designed to reenslave as many black men as possible. When it became a political liability, the state forced the convicts to build a plantation where the prisoners would work. Parchman Prison used to be Parchman Farms which used to be Parchman Plantation.

45th Parallel 3

Jory Mickelson

Cloud

Hum of uncountable, shadowed wings, as though the lake’s reflection

has taken to air. When I hold you I am shadowed, as from a dark

leafed tree, an orchard clouded by fruit, burnished and graspable, easily peeled. It may be enough to see the citrine segments lit within—

the air about my head, like branches crowned in water and light—enough to know and to know and to know your fingers barely around my wrist.

45th Parallel 4

Kimberly Grabowski

I Wanted the Gun in my Mouth

In high school, we investigated how big my mouth was—cups of yogurt, water bottles, my fist. I couldn’t swallow pills when I was little, so I formed a habit of forcing them down my throat with my fingers. Doesn’t hurt. A girl who looks virginal but is really a sex kitten is every man’s dream. Maybe rhythm is the key, sometimes I play a techno song in my head. I start to remember I have a body when the song isn’t playing. Think of my mouth as a womb-space. I’m on a kick, womb-denial. I want to use my mouth because I thought it was never birth-worthy. I ate a jar-full of marshmallow fluff, I think I wanted someone to tell me to stop. That game, “chubby bunny,” kids died from asphyxiation. My girl pretended not to want to kiss me. I had to use my tongue to pry her mouth open passionately. I’m pretending. I want my teeth to cut the insides of my lips. That’s mouthwateringly-good, that blood. And doesn’t it feel nice to gasp like that, delicious like deciding not to drown. Then going back down. I bought lip gloss that burned my skin. It was called Venom. Wasn’t that ravishing, the way it hurt? My eyes were screwed shut, and nothing about me was waterproof. He says you’re so pretty without makeup, and then what did I tell you about wearing makeup. It appears I have a gag reflex, after all. Maybe he has the virgin/ whore thing going on, maybe Madonna and Mary Magdalene. Don’t laugh at me, I thought my finger was on the trigger. We’re supposed to be honest with each other, tell exactly what we want. That’s why his hands push. I’m sore, I can’t move the muscles around my mouth. I’m too tired to say what I want. I wanted the gun in my mouth. Better that than someone pointing it at me and yelling “bang bang.”

45th Parallel 5

River Robert Fromberg

“I told Mr. Sloan that he had nothing to worry about and so he shouldn’t worry.”

—John Dean, testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, June 25, 1973

1.

Sitting in the window seat, looking through the picture window that dominates the small room, what is mostly visible to the boy are needles and branches of evergreen trees. But if he strains just a bit, he can see, through the needles and branches, a sliver of the yellow house across the street. A serious yellow, a dangerous yellow.

He wonders why, at school, the topic of favorite color comes up so frequently, even more frequently than “what is your middle name?” And he wonders why the question seems so freighted with meaning. He answers “blue” because he believes that answer is least likely to lead to any but a neutral reaction. That has proven to be the case. No one has looked askance, and no one has said, “Really? Mine, too.” At first, he believed that the lack of reaction meant the topic had been dropped, and that he was free to proceed as though it had never arisen. However, once someone had glanced at a piece of his coloring in progress that relied on oranges and browns and said, “I thought blue was your favorite color.” From that time on, he colored mostly in blue.

Yellow is his favorite color, the yellow of the house across the street. He accepts as an article of faith that yellow would not be an acceptable answer to “what is your favorite color?” He also recognizes that “yellow” is not the correct word for the color in his mind, that to even name the color would belittle it. The word “favorite,” too, is only a rough approximation of his feeling toward this color.

His mother is standing in the front yard, talking with a neighbor, a woman the boy only vaguely remembers seeing previously

“They left a month ago,” the neighbor says. “They left in the middle of the night.” The neighbor’s enunciation becomes more studied. “The man,” she says, “was being pursued.”

“Oh?” the boy’s mother says.

45th Parallel 6

*

“You just hide behind your trees,” the neighbor says. “You don’t know what’s happening right across the street from you.”

She pauses, as though relieved to have had this opportunity to say something that needed saying for a long time.

The boy knows that the accusation is just and appreciates its clarity. He tucks it away.

At first, when people asked his middle name, he did not reply. However, that only made the questioners ask again and once even drew a crowd who circled him, demanding an answer. The next time he was asked this question, he answered immediately, and the questioner, looking deflated, walked away.

In the winter, the picture window frosts on the inside. When the boy sits on the window seat, he etches lines in the frost, even though he knows that when the frost melts, smudges will remain that will draw attention. The frost reaches only the lower third of the window, and he can still see the evergreen branches, a sliver of the yellow house, and, if he looks to the very top of the window, the winter sky, which seems to hold incredible weight.

Every other summer, a truck goes once up and once down the long street in front of their house, laying down glittering tar. Another truck goes once up and once down the street depositing gravel on top of the tar. For weeks after, as the family car drives on the street, the boy hears the gravel ricocheting off the car’s undercarriage. The fact that his family and their neighbors have the task of tamping down the gravel over a several-week period makes him feel that he is part of a tiny, forgotten community.

The boy thinks that if this were the last picture he ever colored, if he were to die that day, he would work slowly and not worry whether he finished.

At the house across the street, did the father tell the mother and children in the evening that they would be leaving later that night, giving them time to pack? Or did he wake them and tell them they had to leave immediately? Evaluating these option, the boy believes that the terror of each would be different in kind but not degree.

Their car would fill rapidly with their possessions. How did they decide what to take and what to leave? Were the children allowed to choose things to take? He imagines that those things would be limited to things they could hold in their lap as they rode in the car’s back seat.

He does not know how many children are in the family. He has never seen the father or

45th Parallel 7

*

*

*

*

*

mother. However, he has a strong sense that the father wears short-sleeved white dress shirts and black-framed glasses.

Did the man expect his pursuers to arrive the next morning? Or did he expect them that night? Did the family have to keep their voices lowered when packing? Did they have to close the house and car doors silently? Were they worried that the sound of the car starting would draw attention to them?

When the pursuers arrived at the house and found the family gone, would their reaction be rage? How must it feel to the man to know that someone felt such rage toward him?

He imagines that one child, a girl, would be holding some form of stuffed animal whose fur was a dirty grey but that had around its neck a ribbon the same yellow as the house. This child would feel the rage directed toward her father as palpably as though it were directed toward herself.

James Earl Ray shot Martin Luther King, Junior, but has not been caught. According to the radio, James Earl Ray is in the region of the country where the boy lives. That night, the boy waits for James Earl Ray to climb in his window. The window in his room is square and small, perhaps too small for a man to fit through. It is also high, not too high for James Earl Ray to reach, but perhaps just high enough that James Earl Ray would decide to choose another house through whose window to climb. The window lets in very little light, and its height is such that the boy cannot look through it to see the back yard or other houses. Considering the matter logically, the boy thinks, the placement of the window should give him comfort. Yet the boy knows that the placement of the window will make the inevitable arrival of James Earl Ray, wriggling and emerging through the small opening, even more terrifying.

The needles that gather under the evergreen trees are a wonderfully bouncy cushion. They are only sharp if you touch them at the wrong angle.

He has an intimate understanding of each interior door, how to subtly lift, push, pull, and guide each door to open or close without a sound. Because a sound could draw attention.

Every other summer, led by his father, the family stains the redwood siding of their house. The boy loves the weight of the brush and the watery consistency of the stain. He cannot make a mistake. He can slather on the stain any way he wants. He can see no difference in the appearance of the redwood siding, yet his father assures him that this is a good thing that they are doing. The project does not take long. After it is over, the air is still.

2.

Driving along a river. Three parallel lines: road, train tracks, river. A grey day. Early fall.

45th Parallel 8

*

*

*

*

The road and train tracks are raised. Glancing away from his driving, he looks down at the smattering of houses on the stretch of land that is separated from the river by the road and train tracks.

There are no trees. No fences. Viewed from above, the houses are exposed. They are naked.

From many, the content appears to have spilled out—chairs, couches, toys that can be ridden or sat in, pets, tables, cars, trucks, boats. No, “spilled out” is not right. Rather, it is as though, in this neighborhood by the river, a house is not considered the sole container of one’s life. A house is like another chest of drawers or set of shelves. Possessions can be inside the house or outside the house. Life can move fluidly from inside the house to outside the house.

However, he sees no people.

Inside the neighborhood, the drive along the long street is like a tracking shot in an arthouse movie.

He sees two cushioned rocking chairs on a lawn, side by side. Leaves and inscrutable debris have collected beneath the chairs. The debris and the seats of the chairs are almost touching. He imagines the years that have passed, the arc of rocking diminishing each year. Now, the chairs would be able to rock a few inches at best. Within several years, the chairs will disappear entirely.

A white house seems longer than the others, but also shorter, so short it is hard to imagine the inhabitants being able to stand up straight. A girl who lived there later became part of the ensemble of a popular television show and continued to pop up in various roles, although her career has quieted as she has come to occupy middle age.

The street signs are a different color than they once were.

The yellow house has brown trim. The house appears soft. The brown trim appears soft. Were he to touch either, it would be the consistency of cake frosting.

Across the street, the trees are gone. There is no sign of their ever having existed.

The redwood is gone. Instead, there is a deliriously ugly light-blue siding, a light blue the color of signs on small-town drug stores. A light blue that even the owners, upon seeing it covering their house, would stare at a moment, shake their heads, perhaps grin, and shrug.

The picture window has a shadowy curtain inside.

On the lawn next to the house is a large white boat on a trailer. Next to the boat, taller than the house, is a bus the size and type that a moderately successful rock band would use on tour. It is a soupy, swirling brown. Its driver’s side front bumper is coated with layers of duct tape.

Directly in front of the house is a Triumph sports car, in its potency somehow larger than the bus, boat, and house.

45th Parallel 9

He pictures a rock band returning from tour in the dead of night, spilling out of the bus, the band members stumbling giddily toward the house, except for one or two, who hop into the Triumph and zoom down the road along the river toward the all-night convenience mart for essentials.

The vehicles overwhelm the house. Driving past, he can only think about a cartoon he once saw of a muscle-bound man walking a tiny dog. He tries to hold his laugh within pursed lips.

Turning back onto the river road, a thin strip of black, patching a crack in the road, extends ahead, wobbling and disappearing beneath him as he drives. He would be happy to spend the rest of his life studying its movement.

45th Parallel 10

Cheyenne Black

Ten is Too Girl

ten is too girl to know what he looks like naked his finger on the detonator a field of burrs in sand she vomits bubbles of heat pop on her skin prick tick-tock /wait/ wait until the phone rings and she hopes its her mother

scuffed Mary Jane’s with School House Rock punctuation in her head

the blue dog, the one they call a bitch digs under desert scrub for shade—drinks limeade not water because ten is too girl to want water when there’s limeade

she’s hesitant to merge with what’s next? like the first in line after the ambulance

saturday morning I’m trying to wake up make some fucking coffee bring me a beer a bitch

two months in the summer and every other christmas—one foot hovering over the date the wait

trampled under the rodeo bull wicked girl wrong girl too girl bitch we lost her in sight of the Hollywood sign she was wearing /something/ something too little

chin-dripping gulps of limeade ten is too girl to smell like cowboy

45th Parallel 11

Rachael Peckham

Lift

You’ve heard it said that to understand the basic science of flight, just stick your arm out the window of a moving car. The rush of air you feel above and below your hand is the same force of pressure that gives a wing lift, making you think of all the times, growing up on a pig farm in Michigan, you piled in the back of your dad’s farm truck with your siblings. How even the dogs loved to hop aboard and lean out the side, flying headlong into the wind. How effortless and good it feels to sail through open air—less a freedom than a return to the lost memory of being cradled and carried, our first means of movement in the world, aloft in the safest clutch.

But this is not always the case. Sometimes the relinquishing is a reckless one. Years ago, on a distant beach, you and your college roommate catch a lift from some off-duty lieutenants on a spontaneous invitation to surf an hour’s drive up the coast. Even drunk, you request to sit up front, but the cab is already too crowded, and somebody grabs hold of you under the arms, fingers pressing into the padding of your bikini—I got you—and hoists you up onto the bed. The driver guns it and you’re all thrown backward on your butts, laughing obscenities. The one who so courteously lifted you onto the truck pats the space next to him, Here, lie down, and you oblige, letting him curl around you in feigned protection, eliciting a pointed look from your roommate that says you have a boyfriend. Never mind that she’s the one who signed you both up for this joyride, when she knows damned well how you hate piling onto friends’ laps for even a short ride to a party.

You’re shivering, the lieutenant says, hugging you so tightly you’ll wear his cologne on your skin. Normally, you’d place some breathing room between your pelvises, if not push him away altogether, but the truck rounds each curve so fast, his hips keep knocking into your backside with a little too much momentum, like he’s leaning into the turn without any counter-balance. Like he’s colluding with the driver to make it a fun ride. And all the while, you can’t stop the vision of a tight bend up ahead, the driver miscalculating the turn, braking too hard and too late. Will you fishtail? Cross the center lane and plow into the guardrail? Roll over? No matter what, it proves catastrophic for everyone in back, either pitched out or crushed, and at this thought, your fear shifts into sharp anger, not at the driver or your roommate but at yourself for always going along, for what your mother calls the disease to please. And you pull your anger around yourself like a tent, refusing to put so much as a toe in the surf once you’re safely parked on the beach.

Your roommate gets the message, her buzz killed along with yours, and demands that you both sit up front on the way back, or you’re catching the bus. For once, you’re glad for her direct and overbearing tone—the one you’ll never quite harness nor joke about again because your friendship won’t survive graduation. You’ll slowly drift apart, attending each other’s weddings as guests, not bridesmaids, and without so much as a Christmas card to tether you to each other now. And you’ll feel both sadness and relief

45th Parallel 12

at having walked away, for once, only to realize much later that flight has nothing to do with going with the flow, or riding the current or any other cliché. No, it has to do with tension—with enough difference in pressure. It’s the force of resistance that keeps us aloft.

45th Parallel 13

Gathering Evidence Bonnie Arning

I once read how upon learning of her caretaker’s miscarriage, Rita, the chimp, used her fingers to sign: cry-please-person-hug.

Even then, I wondered if all nature’s creatures were designed to respond in this way. On the night of her miscarriage, my wife

set the spent fetus atop a folded towel. She paced as if establishing perimeter—a nervous boundary that marked the edge of where

their country ended and ours could begin. Can I touch it? I asked, unsure if she would allow. Though curious, the fist-sized sack of blood

did not resemble a baby. It looked as though if poked, the membrane might rupture, burst and flood out like a punctured skin of wine. The only

evidence of its once curled form— a single wad of tendons and lumpy head-like bulge. I couldn’t fathom what relationship was meant to form

between myself and that dark tissue until hours after nightfall, when she scooped soil from the base of a tree and tucked her slick bundle into the

dirt. As I covered the mound with brush, I was reminded of Bonobos,

45th Parallel 14

about how at night, the primates gather earth and sticks to construct raised beds, how their care is expressed through subtleties—the primatial parents who carefully kneel to blanket their child in leaves.

45th Parallel 15

Bonnie Arning

—for my grandmother and I thought of you, and your white plume of hair and the white plume of smoke puffing off the head of a state-wide fire—

it was smoke from the fire that killed you, your lungs already pumice each vein a wire wound through stone. How it slowed

your heart—your fist-sized slug, wheezing in the foyer. I have learned

the noise your heart makes is the sound of each valve closing. How violent. What shut.

A whole body battering in time; allthewhile inside us a billion slamming doors, or

the same door opening and shutting in bloody perpetuity.

Who knew? Our refusal to remain open is what keeps us alive.

The heart is such a grinder. Wound until it wouldn’t.

Your heart unfolded like a magician’s fist to release a smoke white dove

blood entering and then—

—poof

And all the papers read: Yesterday, during a thunderstorm, a white Buffalo was born

45th Parallel 16

The coroner takes your body

and flings apart the chest: lungs hard and gray, heart, white as ash.

45th Parallel 17

Mark Hodge

Grandpa and the Duke

Grandpa’s Grave

Every spring, around the anniversary of our Grandpa’s death (none of us remember the exact date), my cousins and I visit his grave. We wear cowboy hats and boots to convince ourselves we are honoring him. In our outfits we look more like a parody than a memorial, more likely to break into an acapella version of “Home on the Range” than bust a bronco or run down an outlaw, but we are pretty sure Grandpa would appreciate the gesture, yet, equally sure he wouldn’t really care one way or the other.

We stand around the grave and try to carry on a conversation in his cowboy speak: “Devil-of-it-is,” “cotton-pickin’,” “mmkay,” “like I told...,” and other things that our Grandpa must have decided he liked the sound of saying before they became his habit. Sometimes we spit, like we have a big chaw in our mouths, then worry that we might have just spit on Grandpa’s grave. Grandpa probably wouldn’t mind that, or our soft hands and dirtless fingernails, or the little tear gathering in my cousin’s eye.

Harry Carey and John Wayne

John Wayne and Ollie Carey both cried after that scene at the end of The Searchers, when he put his hand to his elbow, just as Harry Carey had done so many times in his own films.

Carey had been Wayne’s favorite Western actor when he was growing up. He respected the realism that Carey brought to the genre, and he learned to imitate many of his mannerisms in his own films. Later, Carey would become a kind of surrogate father to the Duke.

Things We Didn’t Know About Each Other

I never knew if my Grandpa’s name was Freeman or Jack. I’m pretty sure one was his first name and one was his middle name. That was the kind of thing that our family didn’t really know about each other. We always just called him Boots.

45th Parallel 18

“End of a way of life...too bad...it’s a good way.” —Hondo Lane

John Wayne’s Feet

Part of the reason for John Wayne’s distinctive, sauntering walk was the fact that he had relatively small feet compared to his large frame.

Grandpa’s Thumb

When he was younger, Grandpa cut off half his thumb with a circular saw. It’s hard for me to imagine him losing concentration and doing such a thing, but it is easy for me to imagine him calmly picking it up and walking to a doctor’s office so they could sew it back on, which he did. But it was too late, so he had a kind of half-thumb, rounded off on the end with no fingernail, the rest of his life. Grandpa was always practical, so he found ways to put the thumb to good use: killing wasps, pushing in loose nails, testing knife blades, whatever the situation might call for. I asked him one time if he still had any feeling in the thumb. He looked at me kind of funny and said, “mmhmm.” Whenever Grandpa talked he always gestured with his thumb, and when he pointed to something he always pointed with his thumb; so the thumb became a commentary on the point he was making, or the object he was indicating. I can’t ever really think of Grandpa without thinking of his thumb.

John Wayne and Acting

John Wayne would never admit that he had ever wanted to become an actor. He liked to tell stories of how he had just stumbled into it, and how he would have preferred to be a prop man if the pay had been as good.

Grandpa’s Clothes

Grandpa always wore denim coveralls, a sweaty cowboy hat, and old, tan boots; unless he was going to a wedding or something like that, then he would wear a western shirt with silver buttons, gray pants, a clean cowboy hat, and black boots. Even in our small town he had grown into an anachronism, but I never thought to ask when he had settled on exactly those clothes. As a kid, I just assumed he had always worn them, even though I had seen pictures of him as a kid during the depression wearing different, though related, clothes (in the pictures the other people are dressed similarly to Grandpa, but I’m also pretty sure they were family).

John Wayne’s Horse

In The Big Trail when John Wayne rides a horse he looks like Shaquille O’Neill riding a donkey. He got better at riding a horse later in his career...or maybe his directors just got him a bigger horse.

Grandpa’s Horse

Grandpa used to have an old horse named Smokey. He said we could ride her if we could

45th Parallel 19

get on her. Grandma would let us have some sugar cubes or carrots so we could lure her over to the barbed-wire fence and climb on. We used to ride her bareback, two at a time, until she got old and cranky and started bucking us off. I never saw Grandpa ride Smokey, though he did say hello to her every morning.

At the Grave

“There was one time, Grandpa said, ‘you boys can play anywhere you want, just don’t go in the Northeast field, where that bull is.’”

“Devil-of-it-is, we didn’t know which field was the ‘Northeast field.’”

“But we were too embarrassed to admit that to Grandpa.”

“So, of course, we ended up in the Northeast field, and sure enough there’s that bull.”

“And he was between us and the damned gate.”

“I remember we looked at each other like “oh shit,” and yelled, “run!” at the exact same time.”

“Probably the fastest we ever run.”

“We went right through a cotton-pickin’ sticker bush...”

“Why didn’t you go around?”

“I remember looking over, as we were in the bush, and seeing the bull running right beside us.”

“He was smart enough to go around.”

“And then we dove under, jumped over, or maybe went right through the barbed-wire fence...”

“Yep, it’s like we told Aunt Sue at the time, we couldn’t even remember, because we were so scared...”

“Then we had to walk back to Grandpa, with cuts and stickers all over our legs, and tell him what-the-devil happened.”

“Was he mad?”

“Ah hell, he wasn’t really mad. He thought we probably learned our lesson.”

“Only thing he said was, ‘is the bull okay?’”

Oliver Hardy

John Wayne looked up to Oliver Hardy.

Things We Didn’t Know About Each Other

My Grandpa didn’t know if his birthday was June 21st or June 22nd . His birth certificate said one and his mom said the other. I didn’t even know his birthday was in the summer until someone told me that as a funny anecdote at his funeral. It wasn’t the kind of thing we knew about each other, though he might have been aware that my birthday was in the spring, because we had cake at his house every year around that time.

“Why’d You Have to Marry That Whore?”

That’s what John Ford said to John Wayne after refusing to attend his second wedding. According to people who probably knew, Chata actually was a prostitute in Mexico, but

45th Parallel 20

I still don’t think Ford was being very generous (it didn’t seem to change how Wayne felt about him though). Duke didn’t really like her hairy legs, but by all accounts he did love Chata. It was also a little stressful for him that she was an alcoholic with a bad temper, and she invited her equally alcoholic mother with an equally bad temper, up from Mexico to live in the spare room, but he drank a lot, too, so he couldn’t really begrudge them that. In the end, the marriage didn’t work out.

Bad Habits

Grandpa didn’t have any bad habits. If he thought something was a bad habit he just quit doing it.

Ain’t

John Wayne always had to remind himself to say “ain’t.”

At the Grave

“Do you guys remember the time that cotton-pickin’ cow kicked Grandma in the nose?”

“Yeah, Grandpa punched that old heifer right in the face.”

“Knocked him flat on his ass.”

“Her ass—a heifer is a girl cow.”

“Mmkay.”

“I swear that cow was out for a few seconds.”

“I’m surprised Grandpa didn’t kill the damned thing.”

“He was practical like that.”

Ward Bond’s Ass

Ward Bond had a humongous ass.

Grandpa’s Discipline

I don’t believe Grandpa ever thought anything he didn’t want to think.

The Mexican Revolution

After the war, John Ford started spending long hours in his room, wrapped in a sheet, drinking heavily, listening to the same recording of songs of the Mexican Revolution over and over.

Louis L’amour

Grandpa had a shelf full of Louis L’amour books. He always liked Western books and

45th Parallel 21

movies, but he never read or watched anything about the war.

Walter Brennan’s Teeth

Walter Brennan used to ask directors if they wanted him to do his scenes “with teeth” or “without.” My Grandpa always did “with teeth.” Until the end. It was strange seeing him like that.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

We used to play upstairs at Grandpa’s house. There was a room up there that seemed to be designed just for us. It was full of old cots, big pieces of foam, Lazy Susan cabinets, two bars with a built-in table between them, and no other furniture. We made baseball fields, forts, zoos, farms, restaurants, and anything else that came to mind, while the adults sat downstairs, in the living room, talking about mortgages, or whatever adults talked about then.

One time, I went downstairs to get a drink, and maybe steal a cookie, and I noticed that all the lights were off in the living room. The adults were sitting quietly, watching the flicker of the TV. I had only known the adults to watch baseball on that TV, and never with the lights off, so I was curious. I snuck in and sat down in time to see “Directed by John Ford” and hear the chorus “Cavalry! Cavalry!” fading into that Technicolor red mist behind the 7th Cavalry flag. The only movie I had ever seen in Technicolor was The Wizard of Oz (every Thanksgiving), so the bright red of the mist and the deep blues of the uniforms gave it all a surreal, dreamy feel to me. I was mesmerized, and forgot to go back upstairs for my turn at bat.

It was the first time that I remember really loving something that the adults also loved. My Aunt Sue had taken us to see Bambi, Peter Pan and Star Wars, and she humored us in the car afterwards as we rattled on about how great those movies were, but she only enjoyed them because we were so excited. But during She Wore a Yellow Ribbon I felt like, for the first time, I was seeing the same thing that the adults were seeing. It was as if they hadn’t noticed, but I had been magically transported into their world, or, rather, that we had all been transported into John Ford’s world.

My aunts talked in hushed tones about watching the same movie with their grandfather at a theater, and how he had been indignant throughout, saying “that ain’t what it was like.” My dad said that he preferred The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but this one was up there, too. Grandpa just sat there, silently.

It was the first time I had seen John Wayne. He resembled Grandpa, in build and features, expressions and demeanor. I knew John Wayne wasn’t Grandpa, and that he wasn’t playing a character that was supposed to be Grandpa, but they became tangled in my mind. When John Wayne gave advice to the younger cavalrymen it felt like Grandpa was giving advice to me. When he talked to Joanne Dru, I thought that must have been how Grandpa was with my aunts when they were first dating boys. And when John Wayne talked to his dead wife at her grave it felt like a presentiment of my Grandma’s death.

I never thought to ask Grandpa what he thought of John Wayne—that somehow seemed a little too personal.

John Wayne and Acting

45th Parallel 22

There are two related criticisms of John Wayne. The first is that he never really acted, that he was just himself in every movie. The second is that he wasn’t really John Wayne, that he was a fake, that he grew up in Los Angeles, and was never really a cowboy.

Victor McLaglen’s Hands

According to Ingrid D. Rowland, Michelangelo and the sculptor of Aule Meteli both exaggerated the size of their figures’ hands “because they carry such a weight of significance.” The same could be said for Victor McLaglen’s hands on film. To watch him spit in his hands and rub them together, wipe his nose, grab a man’s shirt, punch a man in the face, light a cigarette, or hold his hands in front of his face in frustration or consternation, is to feel the physicality of the film world he lives in. Every time his hands are shown on screen it is a cinematographic event, an important part of the mise en scene. His mangled, oversized hands juxtaposed with his battered, smiling face tells us we are in a world of brutality and honor, Hemingway’s world, but with whiskey instead of wine. Where someone like Anthony Quinn seems to be an artist convincing himself to play lovable brutes, McLaglen seems to simply be playing a slightly larger version of himself, and all the authenticity can be seen in how he holds his hands. I sometimes think I would like to have Victor McLaglen’s hands, but I’m not sure I would have enough commitment to the beauty of cinema to go through the act of punching so many men in order to sculpt my hands into such monuments.

My Hand

You can squeeze my hand. I won’t think you’re a sissy.

John Wayne and Acting

“I sat there, trying to be John Wayne.”—John Wayne, on when he found out he had cancer.

Ancient Greeks, Cowboys and Modern Medicine

It is hard to live by the Ancient Greek code of a completed life now. Our society, with modern medicine, conspires against a graceful exit. Modern death may be just about fitting if you have lived as a Woody Allen, with your anxiety on your sleeve, but what if you lived as a John Wayne, with your self-control and honor. There is no simple progression from not being able to get on your horse to dying. When we see that you cannot mount your horse, we lay you in a bed for weeks, months, or even years, and pump you full of medicine so we can watch the façade of pride slowly die, while your body continues its operations, however incompetently, without you. The cowboy’s hope of dying in his sleep is no longer about dying of natural causes instead of being gunned down, it is about dying before your loved ones, and their doctors, know you are sick.

45th Parallel 23

Galloper

You can almost feel John Ford grin, when he has John Wayne (as Brittles) tell Ben Johnson (as Tyree) that he is “well-mounted;” it is almost as if Ford is saying, “watch this,” before Johnson has his big scene where he runs from the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers. I had never seen anyone ride a horse like that. I had only seen people I knew clip-clop along on a fat old horse, in a pasture or on Main Street. Johnson embodies Ford’s idea of the importance of competence, that a man gained respect through being able to do something well, to the benefit of the group. Johnson had that in spades, in his characters and his acting/stunt work. Ben Johnson could have been a painting of the perfect horseman. His torso, arms, and legs all composed on the graceful animal, bursting with kinetic energy, yet tranquil—it was beautiful. I found out much later that many of Ford’s scenes were based on Frederic Remington’s paintings, but Johnson’s riding allows the filmed version to easily surpass the source material. It was after watching Johnson ride that I was really hooked on Westerns, for the rest of my childhood I would wake up every Saturday morning to watch them with my dad.

At the Grave

“You remember that cotton-pickin’ old cur-dog that was out at Grandpa’s place?”

“Had a devil-of-a scar right on his forehead.”

“Grandpa’d never call it ‘his,’ but it always followed him around.”

“And he wouldn’t ever let us feed him...”

“It was like he told Aunt Sue, he didn’t want that dog being dependent.”

“Yep, said he could catch his own rabbits and squirrels...”

“And if we got close to that old dog, Grandpa’d say, ‘That dog don’t take much to pettin’.’”

“Yep.”

“Devil-of-it-is, that made me want to pet the damned thing.”

“You were always stubborn.”

“So, one time I asked Grandpa if he minded if I pet that dog.”

“What’d he say?”

“He said, ‘I told you before not to, but you go on and do what you wanna do.’”

“What’d you do?”

“I tried to pet him.”

“What’d the dog do?”

“Bit the ever-lovin’ shit outta my hand.”

“What’d Grandpa do?”

“Laughed his ass off.”

“I can see that.”

“Grandma got all kinds of mad, and said, ‘Boots, why’d you let that boy pet that dog, when you knew he’d bite him.’”

“And Grandpa?”

“Well, he got kind of serious, and he said, ‘Man learns from gettin’ bit,’ and that was that.”

Two Vultures

“You get those goddamn birds up in that tree right now or one of their heads is gonna be sticking out of your mouth and other head out of your asshole.”—John Wayne to Jack Elam, when he tried to raise the price of the trained vultures, that he had won in a poker game, when they were due to appear in a scene of The Comancheros.

45th Parallel 24

Things We Didn’t Know About Each Other

I sat at my Grandpa’s bedside for an hour with my dad before I realized that he had already died. Maybe that was something else that we didn’t always know about each other.

Explanations

Please allow me to not quite explain myself. I don’t want you to say you love me. They won’t understand, and you are too far gone to clarify—not that you would have if you were still here.

Grandpa’s Wagon

Grandpa had an old wagon that he kept out in front of his house. It was the wagon that his family rode in when they moved up from Texas when he was a kid. We used to play cowboys and Indians in it. Every Fourth of July he would hook Smokey up to the wagon and drive us in the parade. We rode with the horses, at the back, behind the marching bands, four-wheelers, and Shriners in their clown cars. You could always tell the parade was almost over when you saw the horses. They had to be last because they shit all over Main Street.

45th Parallel 25

Necromancer Kathryn Merwin

Lasses Birgitta was an alleged Swedish witch. She was the first woman executed for sorcery in Sweden. Here on the island of windmills & winter, earth disappears slowly. Vanishing waves through another polar night, avalanche of stars, cool shell of the moon. Lips to keyhole, she breathes into the sepulcher, glass & skin glowing with oil & light. She exhales to make ghosts, turns the doorknob: o ne, two, three. Black anemones dagger starlight through crumbling rock: she bathes her hands in honey, her lips in sulphur. She presses her ear to dirt. She calls a name into earth: someone calls back. She whispers into rabbit-holes, paints her skin with their fear. Midnight, frost-girl dancing in the forest, wild, unforgiving.

45th Parallel 26

Amanda Stovicek

Drawing Death

The sun shining on the roof of your mouth. The body in the swamp with a bullet hole found in the morning. The body found under the blackgum tree. The body making necklaces out of cattails and algae. The crows sweating feathers into the water. The sweep of clouds like a wisp of baby’s hair. The space on the steel table empty even when filled. The nocturnal silence of blackgum and cypress uncovering more bodies. The bodies clasped together like necklaces. The bones of their hands, a puddle of pearls. No one touches you like that. No one touches you.

45th Parallel 27

45th Parallel 28

45th Parallel 29

Corey Farrenkopf

You in Another Body

“Describe me. The other me you said you saw,” Hamilton says. Whenever I see photographs of him, a profile picture or polaroid hung on his mother’s refrigerator, it’s a different man. The same man in all, but not the one before me, in real life. The one who puts his arm around my waist, who kisses my neck the way I like.

“Well, you have thin lips,” I say. “You’re really tan. Probably a few inches shorter. Beer gut. Balding. There’s this mole beneath your ear.”

His hand wanders up his neck, searching for the growth. He finds nothing on his unblemished skin and smiles. He waves the waitress over and asks for another beer. I turn down a second seltzer, mine still half full. She walks across the brick patio, heels clicking, and disappears into the cafe. Hamilton leans a muscular arm over the metal railing and tosses a crust of bread to a pair of pigeons.

“Doesn’t sound like me, does it,” he says, without looking away from the birds.

“No, I wouldn’t say so.” I sip from my straw. No, Hamilton is tall. You can count hours at the gym on his biceps. Blonde hair. Clean in every way his counterpart is filthy.

I wanted to ask his mother, that one time he invited me over, who the guy on the refrigerator was. I thought it was some complicated joke. I saw the same man in images of college keg parties and intramural soccer matches, out of breath, slumping by the sidelines. He appeared in every Instagram image and upload Hamilton posted on social media. Some joke.

Hamilton was the kind of person who desired documentation of every occurrence with a photograph. Proof he was alive, that his life wasn’t all television and nine to five. Over four-thousand pictures on Facebook: eating dinner, surfing lessons, a cousin’s baby shower. I’ve scrolled through, trying to find Hamilton’s grinning face—the face before me now—something to let me know he’s there somewhere.

The first time I noticed his doppleganger was in a photo we took inside the Met. It was our third date. My art history professor snagged us discounted tickets. I asked a German woman to take a shot of us next to an upright sarcophagus. The flash flickered before my eyes. Then the German woman said something I couldn’t comprehend as she returned my phone. She might have been holding back a laugh or wishing us a nice day. At first glance, I thought someone had stepped into the shot, that some paunchy Italian man had gotten lost in the exhibit. But when Hamilton saw the image, he smiled, claiming she captured his good side, no tick of humor on his face. I didn’t ask what he meant, afraid of the answer. Now I avoid sharing the frame with him, not knowing who I’ll meet on the screen.

Our paninis arrive, steam wicking off melted cheese, the scent of parmesan and basil floating about. He takes a bite then passes me his smartphone, screen unlocked. It’s opened to his camera. Only the white metal mesh of the table is visible through the lens.

45th Parallel 30

“Take a picture,” he says.

“Shouldn’t I wait until we’re done eating?” I reply, dread souring the bread in my mouth.

He gulps down another bite. “Nah. I want to see what I really look like.” He laughs. My hands shake, lifting the plastic shatter-proof case. Hamilton is still blonde haired, blue eyed, polo commercial ready as my finger hovers over the shutter release. His smile broadens, minute wrinkles crease around his eyes. I press the button.

“Now let me see,” he says, extending a hand.

I hold it back, dropping it level with my hip beneath the table. I block the screen with my palm, eliminating the sun’s glare. I squint. It’s the tan disheveled man, panini in one hand, the other grazing over his thinning scalp. He wears the same collared gray sweater as Hamilton, the same aviators tucked into the neckline.

“Come on, I want to see this other man,” he says, hand reaching across the table. He knocks what’s left of my seltzer over, spilling ice cubes onto the latticed table top. I feel cool water dampen my sock.

“Let me take another,” I say, raising the camera again.

He snatches it from my hand, fingertips tapping the screen to bring up the shot. He flips through previous images and smiles.

“Why? This one looks fine. Could be my new profile pic,” Hamilton says, placing the phone face up on the table. I can see it’s frozen on the image of the tanned man, his bulging gut resting on the edge of the table. Hamilton raises his hand and waves the waitress over, ordering me another drink and napkins for my wet sock.

“It’s a real keeper,” he says, tucking the phone inside his jeans.

“I guess so,” I reply. He doesn’t ask me if I saw the other man on the screen, doesn’t ask if our perceptions have realigned, doesn’t ask who I believe the other guy to be. A slipped dimension. The foreshadowing of a future self. A ghost hiding beneath his fitted t-shirt. Instead he asks if I want a lime for my seltzer.

“No, I think I’m fine without.”

45th Parallel 31

Fuel John Paul Davis

Do cars crave the neat alcohol sting of gasoline spluttering into their tiny round mouths does the A express simmer with pleasure uncoiling its tongue lathering it over the crackling third rail is it wagging its long steel body delighting in the spiciness of voltage does my laptop enjoy suckling its thin wire eager as a puppy before a full bowl its mouth is open all day long do I tantalise it moving my fingers over its many teeth does my bicycle lean against the wall daydreaming of my pumping legs does my press on the pedals have a flavor when I was a child Mom gave me small green stars phosphorescences I could sticker to my bedroom ceiling so I borrowed a star chart from the library & fastened the night to the dark above my bed all day they gulped & gulped in all available light then after sundown sweated it back out of their burning little bodies they were so ravenous they’d swallow any photon but did they prefer certain varietals maybe what bounced from the sun through the window to my cat then a poster or perhaps from the lightbulb to the spine of a book then upward say the light absorbed a small taste of whatever it touched then did they gulp down particle after glowing particle like someone eating strawberries hoping for a truly sweet & rich one pausing a little after to glory in the gift of such luxury when a ray or two reflected off my skin, was I their ambrosia do they know why when I lay my tongue against you soft & firm as you crumple & buck above me do I jones for the sour salt anointing no energy is transferred yet afterward I boil I smolder until sunrise I lie next to you photoluminous.

45th Parallel 32

The List of Broken Things

Wheel on an elephant cart, one petal of the cat’s bell peeled back to extract the metal seed that made noise, a doll’s head, the first cup and also the second, pencil gripped too hard with effort, pencil gripped too hard with anger, a doll’s head, a doll’s head, one nuclear family, the plants growing along the border of the garden, a window where we moved to when we fled, the drought finally, the clouds again and again and the temperature falling,

thermometer that scattered metal fish across the floor, but not the fever, the smallest bone in the foot, a connection made across the buried lines of the sea then: static, that pulpy thing buried in the body, your voice when you spoke in Latin, chair legs dragged through too many climates, ice that continued to crack, first the metal shell of the bullet then the skin above the clavicle, the seal over the door, the seal of the envelope, falling down, the world around me.

45th Parallel 33

West

Sasha

Sasha West

Husbands Are Deadlier Than Terrorists

Valentine’s Day: I cut hearts out of maps, needle them onto twine, and hang them across our rooms.

I kissed the terrorist goodbye so he could take our daughter into his car, wrapped in black coats, off to daycare.

Reader, I married him. Statistics say: if someone’s hands end my life, they will be his. He is

my God’s little body. All the danger of the world sleeps in his muscles.

Still, I place gently my hand on his head, I marvel at his skin, I bring him inside my house, my body, I bear his child.

It is love that keeps the darkness down, love that in the sea cradles. I place my life

here, in my life, with the dangerous stairs, our bathtub and ladder,

45th Parallel 34

him. All could kill me—my daily life in pieces. I say yes and wed his beautiful risk.

45th Parallel 35

Bobby Hannah Gilham

The physical suspicion that something was not going well and that perhaps it never had gone well.

– Julio Cortázar, from Hopscotch , 1966

Eve had read all about the funhouses, and leaving their rotting corpses inside the hotel. She was equally enamored by and in horror of:

All things

Bobby

The freckled face on the back of her milk carton

Her dreams about Jonathan and his…

Her mother’s locked cabinet

The hole beneath her ribs where she kept an EpiPen and a few scraps of paper

This was not a metaphorical hole; rather it had been put there

Oh darling, don’t fret, you’ll get wrinkles.

She’d been reading a lot; perhaps that was the problem. Reading about vampires and homes that held secrets and lovers and extendable walls. She was reading about the Master and his Margarita, about the devil and photography and about Geryon and Herakles, about Little Red Riding Hood and pretending to understand she understood Maria. She was devised as someone literary, by someone who purported to be literary. As if that meant something.

She wanted you to stop and think. Not about her, of course, but about it.

There was a collection of short stories, something she’d been compiling, pulling from library books and stealing from her mother’s extensive collection. She carried the stuffed notebook around, asking others to contribute to it, interviewing her friends at school, her teachers, the talking dog who lived down on Wilshire. She wanted to know: What are you afraid of?

They all had different answers. Needles. Shotguns. Dogs, cops, my mother. My lover. God. The Devil. Incorrectly-modified pronouns. Losing someone, something. An eternal life after life. Falling in love. Dying alone. Dying too soon. Coming back as a toilet brush. Coming back at all. Getting stabbed in the eye. Being tortured. Living through a horror movie. Having to rewatch The Shining. Getting left. Leaving the wrong person. Leaving the right person.

It was all very interesting, she supposed, but no one had an answer to suffice her burning desire. Her small and rapidly developing mind was attempting to reckon with all the things she’d always known but could never properly convey.

What is fear? Am I afraid? Where does everyone else keep their fear, if not in this little cavity behind his or her ribs?

45th Parallel 36

She’d been in a haunted house once as a child. She’d also been in exactly three therapists’ offices. And fifteen drug stores. Two theme parks. One carnival. With Bobby. Today. Right now, in fact.

She was awfully fond of Bobby. And Bobby was not afraid of anything. And that worked out just fine.

She’d always wanted the company and Bobby had a nice way of existing, but not entirely. He didn’t speak much, he didn’t ask for much, and he never snorted. Not like Mr. Frenzen did, whom she hated. Even though Dr. Gonzalez told her she must be mistaken about Mr. Frenzen. He was a dear friend, after all.

But she was not mistaken, and she was not going to think about it anymore.

“When you at last begin to seize those things / which don’t exist, / how much longer will the night need to be?”

And anyway, Eve eventually had a wish to crumple little Bobby up and store him in that compartment behind her ribs, in her chest, where she also kept a few fortune cookie papers and a sliver of an old photograph. To keep him company.

She’d had the hole since she was a toddler, and she didn’t remember a time before. Her mother did, and she’d weep, and weep. But there is no use explaining something to someone who doesn’t know any different because they have nowhere to go but down down down.

So picture this: Bobby and Eve are walking. Maybe they’re holding sweaty palm to sweaty palm, passing the cotton candy stands and arcade games, all sleepy in the frame. Eve will remember how painfully aware she was of the heat and the new, earthy way she smelled on warm days that summer.

Eve thinks about the word earthy and how, to her, an earthy smell was one of corpses, not of earth.

Well, are they so different, honey really?

While walking, Eve suddenly and horribly imagines the day when Bobby might die. She sees his clean white collared shirt beneath a small suit, wonders absently about the conversations that might go into the planning of a child’s wake.

“Well, does lasagna seem too, I don’t know, festive?”

And Eve pictures how his sweet face might look in the casket, his thin lips hiding a jagged upper jaw line. He really does have terrible teeth, Eve thinks now, giggling to herself while Bobby shoots at disappearing bullseyes. He wants to win her a stuffed bear and she wants to pull his teeth out, start fresh.

She thinks she might be able to do it better. Oh, she would ask first of course! It’d only be if he wanted her to. Come now. A few inches taller than Bobby, Eve has to shrug her shoulder to hold his hand. Realizing this, Eve suddenly knows that they are incompatible, she and Bobby, and that somehow this matters to her plan. She’d only seen a few sex scenes from movies, nothing too racy, but she knows that if they don’t fit together, they are not meant to be. Eve so badly wants to fit with somebody. To crawl under their skin and never leave. She just wants someone to wear, to live so fully in their self that the two might become inseparable, that they might share the same thoughts, the same dreams, that they might speak in short brain waves, ordering the same dish at a restaurant and finding humor and sickness and love in all the same places. In all the right places.

Eve wants so badly to know someone. Inside out. And she wants Bobby. Mismatching parts or not. Never to control Bobby, though; she just wanted in.

She wants to wander down the corridors of his arteries, lit by red paper lanterns and a half-burned string of Christmas lights in an apartment uptown where Bobby will never actually live. She wants to slide drunkenly down the walls, her tights full of runs,

45th Parallel 37

hair a chaotic mess and mind free for once. Bump like cars into partygoers, creeping slowly towards a door at the end of the hallway, light thumping, burning, some psychedelic, dissonant song is playing, and it’s all there for her, like a scene she would never allow to play out. The music is climaxing, her fingers are burning and behind the door, fun mirrors, only a whole mess of red.

Smile.

Smile.

That’s all Eve really wants. To find her connection.

But Eve does feel a great many things, not least of which is fascination.

She pulls away from Bobby’s hand, reaching into her notebook stuffed with fear. She’s stolen pages from library books, her mother’s collection, her neighbor’s journal, the recipe book from her aunt.

What are you afraid of?

She smoothes a sheet and reads to him just outside the funhouse on the pier, near the lazy waves and prickling sunlight. It really is a beautiful day.

“I feel that the period will sooner or later arrive when I must abandon life and reason all together in some struggle with the grim phantasm FEAR,” she reads.

Bobby is not stupid, but he is twelve, and there’s that.

“What else is in that notebook?” he asks. Eve wonders if she makes him nervous. Perhaps his mother always taught him to ask questions when he is uncomfortable. To get to know people.

Bobby really was an awfully polite little boy. Eve really, truly, did not want him to change. Not a day. She wanted him to stay like this forever. Sweet and earnest and soft. Eve felt it to be the tragedy [were she old enough to fully understand that word] of the opposite sex. To become slowly transformed, to grow aggressive and brash and brazen. Eve knew the tragedy of women, and unlike her mother and those women in her family before, she was not afraid of it. Although, perhaps she should be.

Bobby’s funeral was held on a Sunday at the Presbyterian church on Wayward with a wake that followed at the Whitaker’s house down the street. They served lasagna. Eve was not invited.

The casket was closed, but Lillian Whitaker had insisted her little Bobby wear the altered suit. She could hardly finish that thought though because last summer they were celebrating new love, new life, hugging family and drinking and she and Bobby had shared a dance to Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me.” There were tea lights in all the birch trees. And that all was a thousand years ago, now, a different dimension, a different era, a kaleidoscope. Like dinosaurs and asteroids and astrophysicists and the discovery of penicillin; to Bobby’s mother, there was no time, no space. Only Bobby. And no Bobby. His father Robert greeted the guests and his mother Lillian sat in the bedroom and tried to focus on inflating her lungs, slowly. In. Out. In. Hold. Out.

Eve imagined the woman sitting there, sobbing, breathing into a bag, going through her son’s notebooks and toy boxes and making an infinite scene. Webbed fingers crawling through toy train sets, wrapping in and around bedposts, cocooning there forever.

But Eve was not an adult, and so she did not understand, yet.

Bobby’s mother merely sat in silence, breathing in. And out. And in. Hold. Out. The coroner was able to do quite a lot; there was even talk of considering an open casket. But Lillian would have none-of-it-Robert.

But he did have a fairly easy job, really, as many of the organs were never found, and those that were, Mr. Whitaker had asked be donated. A little girl named Suze would get a brand new liver because of Eve and she would grow to do wonderful and terrible

45th Parallel 38

things. I’m sorry, not because of Eve. Because of Bobby. Because Bobby died. Eve had nothing to do with it, surely. This is coming out all wrong.

Which, in turn, means that Bobby was alive (somewhat) when they found him for the organs to be salvageable, as you may have deduced.

Eve doesn’t like to pander, so there will be none of that.

But for the morbidly curious, the coroner was able to remove twenty or so crumpled up sheets of paper, of library book papers, actually, from inside his ribs. From stories about the long nights, about the houses falling, the clocks ticking, the hearts beating, the knives reeling, eyes flashing, about the jungle, the carnival, the funhouse.

That was the construct of which they found him in. Stuffed politely with beautiful words, stained in, well you know.

“Therefore he will construct funhouses for others and be their secret operator –though he would rather be among the lovers for whom funhouses are designed,” one cop read aloud from the papers. The words, her words!

And Eve couldn’t help but wonder if she’d misunderstood the whole thing, just a bit. But she did so wish Bobby could’ve seen it, anyway. Well, really seen it. All of it. The little girl stumbling into the funhouse minutes after them, searching, huffing, lost lost lost. The steps getting closer, further, mirrors warping closer, further, Bobby’s sweet and shallowing breath.

Oh you really should have been there!

The little girl’s name was Martha Carson and she would overdose fifteen years later on (insert your medication of choice) while her toddler Rachel slept in the next room. Just before she gave it all up, Martha so badly wanted to write down the strange smells recurring from that day as a child near the ocean. Inside the funhouse.

Earthy, almost. Like paper and pipes and late nights in the library and lost nights in a stranger’s bed and the smell of birth and of removed organs lurking somewhere behind a funhouse, maybe near the garbage cans, festering somewhere behind a set of ribs, somewhere stuffed with little snippets of love letters and grave misunderstandings.

Bobby tried to explain it to the paramedic, too. The smells-sounds-sights.

The horror!

But the oxygen mask was sucking in all his words and he died before they got to the hospital.

And really, I wasn’t there, so I probably shouldn’t say another word.

45th Parallel 39

Krys Malcolm Belc

The Broad Street Line

You always hold my hand at night, in the beginning. You’re afraid of campus, of the thick woods, the heavy black. It’s quiet; the nerds are asleep. You talk a lot, talk all the time; I learn everything about you, unbelievably fast, and keep my secrets. It’s impossible to explain how dark my childhood room was, how lonely. Months later I sleep with you in the twin bed you slept in before you left home, even though your parents think I’m on the floor. The Long Island Railroad roars by every so often. It’s New York City; people come and go and come again, all night. This is the normal you came from.

When you graduate and move to Philadelphia, you live on the fourth floor of an apartment building. Apartment 4D. At night with the windows open we hear loud echoes, voices bouncing off the buildings: rugby players from the University of Pennsylvania singing and chanting in a wild rumpus; couples screaming outside bars. One night, a pop. You fucking shot me, we hear. You shot me with a cap gun, what the fuck? The trolley comes by every few minutes, rattling like coins shaken in a piggy bank.

You have a job that’s the stuff of nightmares. All day you perform experiments on people with schizophrenia. We call them studies, you say. But I’m not convinced. Electrodes are involved, to measure responses, reflexes. Sometimes you sit with them for ten hours, alone. It’s not Law & Order, you say. These people are not violent. The patients come day after day; there are so many in this city. You videotape them being startled by a loud tone. You test their sense of smell; I don’t get why. It’s good to learn more about this disease – I understand that – but I also think about tiny electrodes on their eyelids, the men with flat faces, loud beeping noises, a panic button behind your chair. You’re not afraid.

But you won’t take the Broad Street Line. I ask you to meet me for dinner in South Philly. We’re driving, right? You ask nervously. I’ve known you a year and think I know your fears: quiet, dark places. Your parents finding out I don’t sleep on your floor. Having to say a word you’ve never read for the first time out loud. Especially if it has a lot of vowels. You grew up in Warsaw before the wall fell. You became a New Yorker. The Broad Street line is, like all things in Philadelphia when you are from New York, a miniature version of the thing. It runs for a few miles, straight up and down underneath a single street. There’s nothing to fear there.

You could get hammered, you say. A guy was. You saw it on the news. I ask where you saw the news – you have no TV – but you don’t remember. That’s not important, you say, annoyed that I question everything. It happened. Hammered in broad daylight. No one called anyone.

45th Parallel 40

I look it up. I’m someone who looks things up. The victim was a hospital worker, a tech, who fell asleep on the train. The man who hammered him had a five-year-old standing next to him, his son. A hammer in a duffel bag. Screamed something about God. These are the ones you tell stories about: the ones who think they’re God, think God is talking to them, think they have something to teach you about God and the universe and all the things in the world we should fear.

Sometimes after work you come to see me on the dark campus where I still live, but you take a regular train, a commuter train where they still issue paper tickets. Trains with quiet cars. Trains you can sleep on. When we go to sleep in my dorm room, it is completely silent. A fearful thing, now. I’m afraid. I’m afraid that the world is not made for people like us. I’m afraid of you locking yourself in small rooms with strange people all day, people who think they can feel sounds, people who think they are God, people who won’t startle no matter how loud the tones are. I’m afraid I’ll never lie in your childhood bed again, never hear the LIRR scream by again. We go to sleep: quiet, afraid.

45th Parallel 41

Krys Malcolm Belc

Your Father, the Cab Driver

Has perfected the art of speaking much and saying little.

He reads widely; listens to NPR. He can talk to anyone about non-controversial subjects for hours. The weather. Nature. International vacations. Car repair. Traffic. Baking bread. Local high schools and colleges. He would never say so to your face but he is proud of you: Stuyvesant, Swarthmore, Penn; he drives around waiting for other parents who will know all that these places mean to a cab driver’s daughter.

For Christmas and birthdays, you send him sad, soulful woman singers on CD. Norah Jones. Adele. Regina Spektor. He sends you a long text message from his cab one night; it can only be described as poetry. He describes driving through Manhattan with his windows down, in the middle of the night, listening to Begin to Hope.

He spends evenings idling in the taxi line at JFK among his Polish buddies, some of whom barely speak the language he long ago mastered beyond mastery. They talk about their kids. Bridges and tunnels. Soccer. The evils of the Taxi and Limousine Commission. But his art, the art of waiting and of talking, is dying.

In 2005, in an interview for the New York Times, he says: “With cellphones, nobody wants to talk to the driver anymore. Even on a five-minute trip, they always think of some long-lost aunt they can call.” When I ride in his cab, I cannot play on my cellphone; I want to make a good impression. Having perfected the art of speaking much and saying little, your father actively chooses not to employ these skills with me.

He asks what I study; when I tell him African American History, he says, Really? Why? That sounds depressing. He asks about my family: where they live, the names of all my siblings. He judges them for being too big and too wealthy without saying so. I memorize his taxi number so I know who I’m hiding from. You tell me I’m being ridiculous – Do you know how many cabs there are in this city? But I say one can never be too careful about these things.

Later, after a years-long series of awkward cab rides and awkward dinners, he expresses confusion at your choice to marry me. All this about being gay, and you go and choose someone who is barely a woman to begin with? When you tell me this later, I can see it: I picture him drumming his steering wheel, not waiting for your answer. Opening his windows and pressing play.

45th Parallel 42

F. Daniel Rzcinek

Leafmold

Time to get to work: giant haystacks, the first freeze of November, longing like a broken hammock, jackpot of loneliness. The jackpines redacted. The deer hit by traffic falls dead outside your front door, bloodying the morning paper. Logic of herons. The half-full gas can on the garage’s stained floor. The drums begin like this. Nephew of an albatross, orphan of a frigate. Take a long break and then coast on silence. After the island. I promised to cook dinner and forgot. The over-examined life is all I am left with. Churn the farm, my dream commanded. The rest was lost. A psychic broadcast from the deck of the Shirley Irene as it makes the crossing from Kelleys Island to the coast of Ohio. The shallow end of the bathtub. Trees creep up to the gunwales and the mouth drops, spilling cars. Six freshly shot buffleheads add choral static to the mainland’s drone. No shut-offs. At the junction of water and electric, the heels of shoppers go clicking by. This is not a form of song yet it suggests it. We go for full integration and the resulting enchilada known as whole. Laughter of swans in the fog. Fog like a bow bent at the sky. Sky like a chant: silver blue silver, silver blue blue.

45th Parallel 43

The Insurrection at Fort Bob Ross

Happy little trees fell one by one with an unhappy sound, and the sky ran many-colored toward the approximate horizon. We could hear catcalls in Russian sifting through the gaps in the wall—“I might not know art, but I know what I like”, “Absence of intent is not method”—that sort of thing.