TABLE OF CONTENTS

Letter From The Editors and Masthead 2

Into The Unkown - Shelby Mills 3

Grasshopper Hymns - Bri Stokes 4

Mùa Mưa Bên Sông Hương - Adalyn Ngo 5

Together by Ourselves - Maria Pianelli Blair 6

Foam - Paddy Qiu 7

Stash - Michael Montlack 8

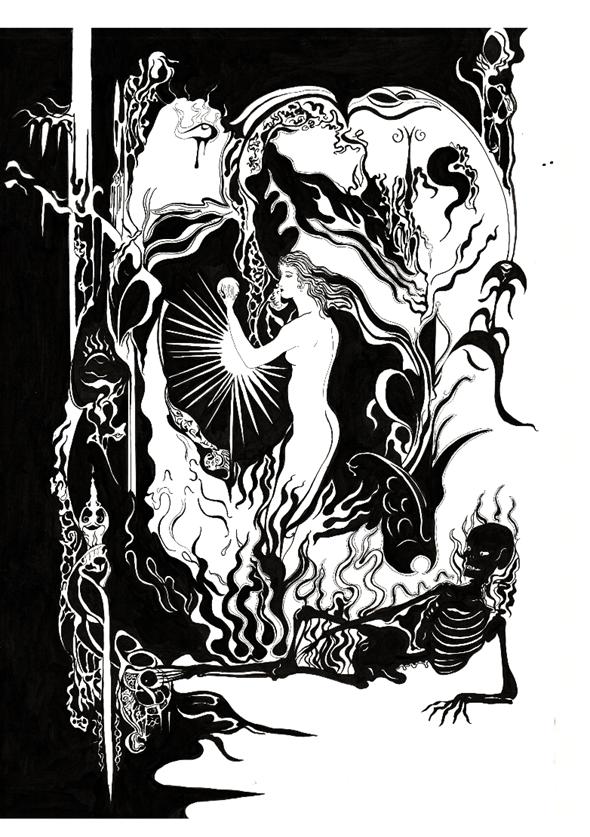

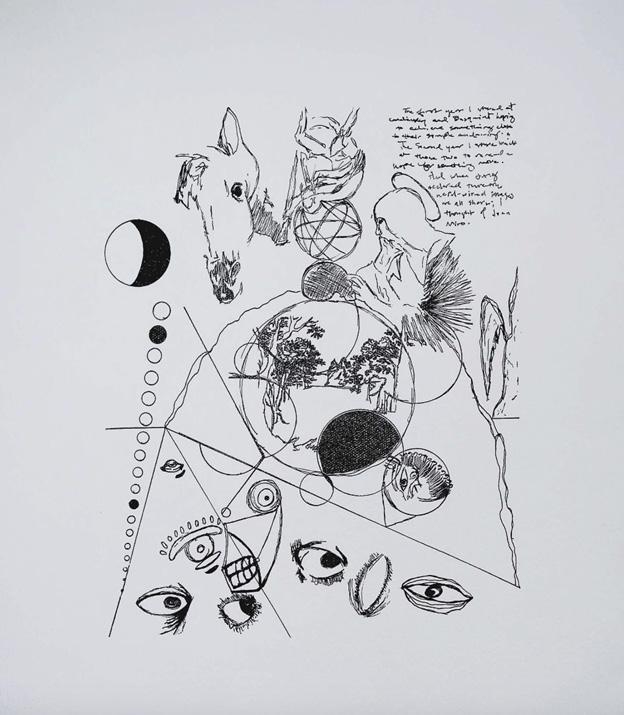

Eros And Thantos - Joseph Milne 9

Evicted - Maurice Norman 10

Hibiscus - Alyson Miller 11

Elvis and the Archangel - Jonathan Jones - 12

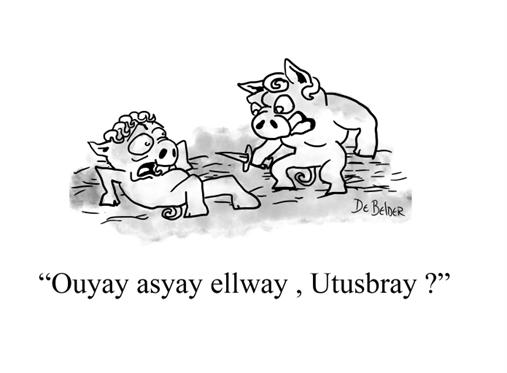

Pig Latin - Sam De Belder 13

For Mother’s Day - Tiffany Promise 14

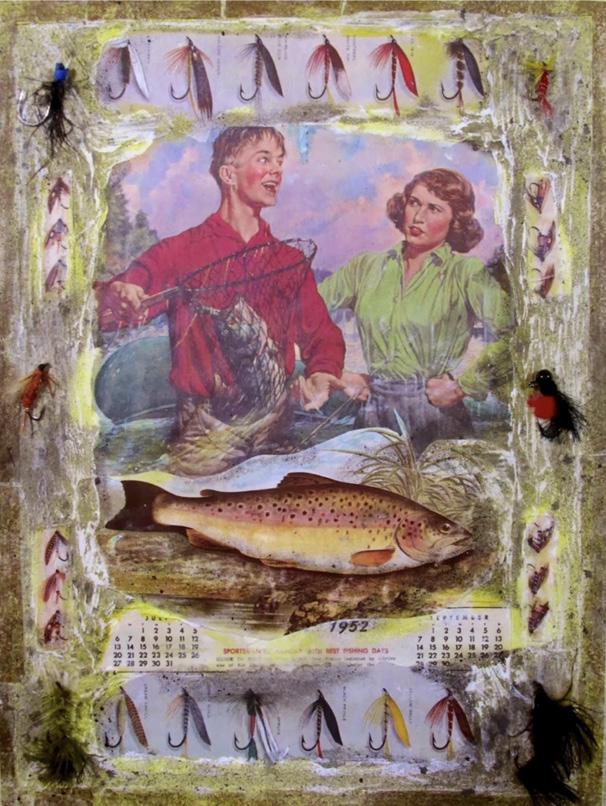

Tippy Canoe - Gj Gillespie 15

Howe Offal - Gia Bacchetta 16 - 31

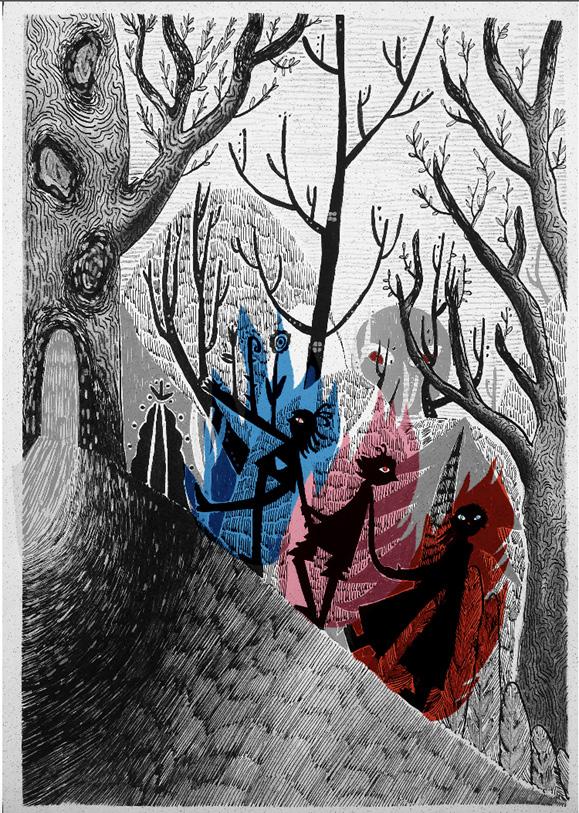

Aishling, Vanja, Aoife - Pauli Pokryvková 32

The Collector - Lucy Zhang 33 - 37

Maina - Lauren Aschoff 38

Dorian Avocado - Sam De Belder 41

The Random Dissolution of Everyhting but a Rake - Bob Bires 42 - 44

Artist Biographies 46

The Pandemic-Resilient Cities Science Fiction Writing Contest

1st Place - Martha Hipley 47

2nd Place – Scott Batson 55

3rd Place – Emma Space 74

4th Place – Shoshana Groom 87

Honerable Mentions 114

Dear Readers,

It is with great pleasure that I present to you the ninth issue of 45th Parallel and the work of our amazing contributors. As you read this issue, I hope yo will be as impacted as our team was by the quality of the following published pieces and the writers and arts behind them.

This year, we’ve had the privilege to work with the Pandemic Resilient Cities Project to run their Sci-Fi writing contest. We have the honor of publishing the winning submissions that have imagined a world where pandemic resilience has been achieved, and all the subsequent implications of such a future. In the wake of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, I believe that art has a way of encapsulating the past so that we might carry the weight of our future a little bit lighter.

I don’t think we could’ve found a more perfect cover, or more appropriate title, than Shelby Mills’ vibrant “Into the Unknown.” Due to the nature of 45th Parallel’s staff of two year masters students, each issue is headed by a fresh team of editors, resulting in a unique publication every June. This year, I believe we’ve captured this ever-evolving patchwork aesthetic quite well—beginning by plunging deeply upwards into the rich and intoxicating blends of stark red and ending with a vision forward through pandemic resilience. I invite you into a dreamy collage of art, poetry, and prose that explore our minds, our environments, and our futures.

I often argue that every poem is a love poem, as anything worth creating must come from a passion within its creator. 45th Parallel too, is a love poem. Even through the most mournful, most angry, pieces of artwork we come across, the love that went into crafting it is still so obvious. We hope you feel this love as you read and take in each poem, story, and artwork included in this issue.

With love,

Amanda Younglund Editor-in-Chief

MASTHEAD

Amanda Younglund: Managing

Editor

Miranda Kross: Prose Editor

Jess Bajorek & J. Webster: Poetry Editors

Grace Hime: Art & Comics Editor

Layne Bolen: Design Intern

Grasshopper Hymns:

You give shape to the howling. You make weightlessness of corpses. The night defines itself by your insistence, like the call of a raven against the whistling air, and I draw down the moon as the evening unwinds for you, and I mimic the cicadas with the poetry in my lungs, and you till the stubborn fields ‘till I burst from summer’s catacombs, all alight in lavender and dusted with honeybees, with oak-colored moths, with the fire of sunrise and the curiosity of arachnids (lithe limbs and peacock-painted eyes), de-fanged; drained of venom; pulled through the clouds like constellations, and vibrating, finally, with the swinging of silence.

For Mother’s Day1

Gank a bouquet from the Fill’er Up. Steal the penny pool while you’re at it. Ain’t a single-backed beast in sight, just a bunch of boys who sling titty2 around in casual convo. Beware: Titty Boys grub the sunset color from your eyes and suffocate your sweetmeats. Like a plastic bag over the head, clenched at the throat. How Jeremiah had to kill that deer. Writhing on the side of the road—a gash through her middle—she begged for sweet release. Jeremiah was your first kiss: at fourteen, giddy on Diet Pepsi and Doom Generation3 Titty Boy will be your last. In his whole bag-of-jellyfish body, his crooked fang is the only solid thing. So, quick! Gobble up that wedding cake—don’t dare stuff it in the deep freeze4— and if you happen to find a tiny baby5 baked inside, eat that too. Get crackin’ on the book you started months ago, the one with the verbs that glut you. But if you accidentally drop it in the tub, and if a waterlogged cover happens to curl like the thin vermilion6 plastic of a fortunetelling fish7, go ahead and let it spill your fortune across the floor. Spittin’ image of those grimy octagons that pooled Nancy’s8 blood.

1 In 1918, Anna Jarvis designated the second Monday in May as Mother’s Day. The singular possessive signifies it as a day for each individual family to celebrate their own mother rather than a celebration of mothers worldwide. My family’s nuclear ceremony—spawning decades—starts with breakfast in bed (an array of snacks that are easily unwrapped & maybe some food-colored scrambleds) and ends with a phone off the hook.

2 From the Middle English “titte.” Referring to a woman’s breast as a “tit” was not considered impolite until the second half of the nineteenth century. Other useful slang: milk-jugs, boobies, knockers, tatas, melons, coconuts, bangers, puppies, buds, maracas, fun-bags. In my family, we call small ones “chiggers,” after that red biting mite that’s tinier than the period at the end of this sentence.

3 Directed by Gregg Araki in 1995, this madcap, raunchy crime drama stars James DuVal and Rose McGowan. Sometimes I’m unsure if my memories are actually my memories, or if they’re Teenage Apocalypse film-stills lodged in my amygdala.

4 Starting in the early 19th century, married couples ritualistically imbibed the mummified top tier of their wedding cake at the christening of their first-born. Shit sandwiches were available for nonchristenings and second-borns.

5 The baby should be pinkie-sized, gummy and boneless, different than the porcelain Christ baby that’s baked inside King Cakes, which are popular in Louisiana at Mardi Gras. Cake babies are said to bring luck. Little godsends that get stuck in one’s teeth.

6 Otherwise known as reddish-orange, vermilion is made from powdered cinnabar, a form of mercury sulfide. Mom had a tube of mercury in her underwear drawer; she’d let us slither it in our palms as a prize for complaisance. Mercury poisoning can cause kidney failure, tremors, and cognitive dysfunction.

7 Trademarked as Fortune Teller Miracle Fish, this classic novelty was originally made in Japan in the 1930s. It is composed of sodium polyacrylate—the same chemical used in disposable diapers—and is activated by palm sweat. I always skew “fickle,” but other fortune options include: jealous, indifferent, in love, false personality, passionate and/or dead.

8 Nancy Laura Spungen (1958-1978) was the girlfriend of the Sex Pistols’ bassist, Sid Vicious. On October 12th, her body was found on the bathroom floor of the Chelsea Hotel in NYC with a stab wound to the abdomen. The murder weapon was identified as the Jaguar K-11 hunting knife that Spungen had purchased for Vicious a few days prior. Vicious was arrested and charged with seconddegree murder. He pled guilty, was released on bail, and overdosed 4 months later. It’s unclear whether Vicious’s mother fulfilled his last wish by sprinkling his ashes atop Spungen’s grave, or if she clumsily junked the urn at Heathrow Airport in London. Mercurial mothers spawn decades.

Aunt Maria brought confetti to Mom’s funeral. Not the paper kind but the Italian, sugar almonds, traditionally a wedding favor. Dad’s friend Donald brought a banquet of cleaned bass, freshly

There’s enough Saran Wrap and aluminum foil here to clothe a giant. Mom would’ve loved it. She ate just about anything. If she were here, she’d sneak in a joke or two about Aunt Maria’s confetti or Rick’s short ribs. She’d say something caustic and unfeeling about one of the neighbors. She’d bring a touch of humor, a sprinkle of bitterness, something to delay the “hard feelings.” That’s what she called them.

another neighbor and a friend of Mom’s

“Greta Rossi,” she begins, “was a dear friend of mine… What a…what a… fascinating young woman that ” she coughs, raising a bony finger and pointing to Dad, “you know better than anyone how that woman could cook.” A few chuckles ring out. “S doorstep after my knee operation. I’d invite her in, and we would talk for an hour or two over tea. She

lived such a full life, for someone so young.” The woman takes off her glasses, wipes her eyes, and stifles a sob. “I know… I know she is still with us, in one form or another.”

I’m used to hearing Mom’s echoes. They began about a month after she passed. It’s been two years since The best thing about funerals in the Deep South is the food, and you haven’t touched any of it. Look at this spread. Y’all better not let any of it go to waste.

Mom was cremated. For months she sat in a small Postal Service box marked “Human Remains” on a chair in the corner of the dining room, like some kind of possessed object. Dad and I didn’t know what to the back of a closet, it just didn’t feel right. It’s almost as if she was willing us not to do anything at all. We couldn’t have a funeral in the midst

She mostly talks about food, if I’m being honest. For a stick

Nat, darling, you and Dad, you’re both sad poets… Life brings you hard feelings, and you have to learn to especially today, she’s been echoing constantly. I’m baffled. To Mom, death was just another step in life.

I can’t remember what, but I’m sure it was small

read “Howe Offal,” a pun on her marriage name. Our freezer is still stuffed with some of her experiments. She’ll be feeding us well after her death. They’re not experiments. Give me some credit, Natalia. You want Dad’s TV dinners for the rest of your can, and shoot them. That’s how they do it in Ap

“And I just… I just… don’t know what I’m going to do, now that she’s no longer here. Everytime I get a

” the woman pauses, sniffs, and continues. “I think it’s her. I think it’s Greta but then I realize I’m just hearing things.”

Ridge Mountains of Georgia. He’s a somber, dramatic ma

GIA BACCHETTA

When we moved to Hiawassee from suburban Atlanta, I was six. We moved into a robin’s

“Oh my dear Greta. How awful…” The old woman stops speaking. Dad has joined her at the podium. “Greta.”

I can’t tell if Mom’s voice sounds heavy or not.

“I know this is a long time coming. We wanted to have a gathering for you, to celebrate you, but the timing never seemed right.” Dad shrugs. “It never is. You said that yourself. I should have listened to to bestow from time to time.”

Dad can’t hear you. Why do you only speak to me?

“Our first date, you ordered a massive steak with chimichurri, and I ordered a side Caesar. You told me the allure. And, of course, your beauty and kindness.”

“Essentially, you ate, and I spoke. And we had a lovely two hours. I told you about Till Eulenspiegel, e that that dinner had been the most fun you’d had in years. You had such a hunger for life, for stories. And you loved that I dabbled in dark comedy.”

“‘Why are there so many stories about eating children?’ You asked.” Dad laughs. “‘Is that a German thing?’ And I think I answered with some nonsense about symbolic language and the harsh realities of mother trope came from the fact that, very often, fathers remarried younger women… I’m sorry.” Dad chuckles and clears his throat. A few people laugh. “I’ve gone on a ta “

“ let’s all eat. Enjoy some of this food. Enough of me speaking. Greta would have wanted us to enjoy ourselves, especially with the fine food you all graciously prepared.” A few Amens ring from the crowd. Amen. A fig for the ‘morrow! I walk to the table with Donald’s bass. The skin, crispy and glistening, looks tasty. I can’t figure out if I’m nauseous from hunger or disgust. I scoop a tiny bit and put it on my paper plate. I take a bite. It’s

I feel like I’m gonna wretch.

Why’d you spit it out? They’re the best part

I’ve always hated my hands. They're too large to be beautiful, too thick to be delicate.

They’re almost manish with their wide palms, girthy fingers, plump tips, and hardened

father's children is because we inherited his chubby toes and fingers. We don’t look like

I’ve always hated my hands. While my father made them chubby and my mother scattered

It’s the worst during winter. When the first snow comes, the biting air splits my grandmother's skin open and leaves her hands white, red, and veiny. She’ll caress my face and I’ll shudder at the sensation of her dry palms scratching my cheeks. My hands will look just like hers when I grow old. She’ll be gone then, but in the winter I’ll

I’ll rest my dry palms against my wrinkled cheeks. Then, I’ll close my eyes and my

I’ve always hated my hands. In middle school we’d stand in a circle, one of us with our hand

“Don’t flex them,” a friend would warn me, “if you’re moving them, we can't see”.

“Sorry, looks like you’re a lesbian,” my friend declared and the rest laughed.

were defiant. I knew that her hands were smaller than mine because we’d compared them

“The fingers are the same, what does that mean?”

Finally, my friend retreated her hand, “maybe it means I’m bisexual,” she joked. Because it

I’ve always hated my hands. Sometimes I stretch out my fingers, just like we did in middle school, and I’ll check if my index finger is still shorter than my ring finger. Sometimes I’ll

I’ve always hated my hands. Last winter my mom decorated the wall in the hallway with a Like scars from a former lifetime, these were the marks they’d left behind.

I’ve always hated my hands. I kneeled on the floor and placed my hand on my bed, palm

I’ve always hated my hands. I raised the hammer and I pictured the cool steel passing through

exposed to the sun and my eyes closed. I won’t remember the hammer or the best friend with beside me, taking the opportunity to observe me while I’m not looking, their eyes slowly scanning each inch of my skin. They’ll say something like, “I never noticed you had so many beauty marks before” and I’ll give them a lazy smile, responding while my eyes are still closed, “They're usually covered since they're just on my upper thighs and shoulders”.

The Collector

When the Collector comes for our hands, we run. Honestly, I would rather give up my hands than live in fear of the Collector plucking our hearts from our chests as penance. It’s all because Yao would rather die than lose his ability to embroider flowers into our cheap robes that have been patched so many times they’re made more of rags than the original silk. I’m not nearly as good as Yao at embroidering, but because he decides to run instead of severing a hand, I choose to leave with him. There’s not much point in continuing to analyze the curves of ducks and pomegranates and bamboo and peonies, images I’ve never been able to embroider quite right, stabbing my thumbs with the needle every time I tried to round a corner. Most of the time, Yao completes my assignments and I buy him his favorite fried seaworm skewers in exchange. Yao insists on fleeing to the mountains where the Collector is least likely to search, and for good reason. Tigers and snakes roam the mountains, and not the ones that move slow enough you can hunt and skin, but the ones who outrun arrows. Even the Collector struggles with them you can’t collect from something that moves too fast to catch. We leave early morning before the adults have a chance to search for us, this month’s sacrifices. I tie a handkerchief stitched with orchids and gold leaves to my wrist, a gift from Yao after my birthday. He’d spent six months on it. We decide to use them to keep an eye on each other since the mountains are notorious for leading groups astray, and the gold threads glint even under moonlight.

The first time we saw the Collector eat, it was not a heart or a hand, but a lung. The sacrifice volunteered willingly, and so the only thing stolen was her lung. She’d been a singer, the best in town, known to even serenade wolves and harmonize their howls. She lived on the outskirts of town with her husband whom none of us liked a stingy man with a balding scalp that smelled like vinegar and rice wine and whenever you passed their home (which was every time you left or entered town), you could hear the bashing of pots and screams and clangs like someone was trying to knock the house’s walls down. But the woman sang better than any trained chorus, better even than the morning bird courtship rituals. Yao said the woman was churning her misery into music. I wondered if that made her any happier.

The Collector had reached its long claw-like fingers into the woman’s chest, each nail sinking through her rib cage like her skin and bone were made of foam rather than flesh. When his hand emerged holding a bloody organ, slick and wet within his phantom palm, the singer collapsed to the ground, her chest sealed shut like nothing had entered to begin with. The Collector swallowed the lung in one take. We could not see where the organ had gone since the Collector’s body resembled cloaks of smog more than a physical vessel. Yao theorized the Collector did not eat the lung at all but rather deposited it somewhere secret. I didn’t think it made a difference the woman no longer had her lung eaten or not. She no longer sang afterward, and her husband fell quiet too. We didn’t see or hear either of them much after that.

But what we did get was a full harvest: the apricot trees that had rotted became strong, the bok choy raided by insects returned to a state of vibrant green, the river that had been polluted by an unknown substance and subsequently killed all the fish seemed clean once again.

As Yao and I begin the trek up the mountain, a constant upward slope with few breaks in the path, I loosen the handkerchief on my wrist, the glimmering threads itchy against my skin.

“Do you think we’re leaving everyone to die?” I ask.

Yao snorts. “They’ll just find someone else to hand to the Collector. It doesn’t make a difference whether it’s us or them.”

“But what if they can’t find anyone?”

“An unlikely story.”

I exhale with each step, too tired to muster a reply. Even though Yao spends more time sitting and embroidering than I do, his endurance outshines mine. He claims it’s a characteristic of a true craftsman the ability to stay quiet and grind despite physical pain but I think Yao just won’t admit he walks insane distances at night because he can’t sleep. I call it the Art disease he even forgets to eat for days while embroidering, and I’ll have to shove a bowl of congee and leftover stale buns in his face to get him to realize his swaying and dizziness are due to depleted sugar stores.

I trail behind Yao who hasn’t slowed at all. “Let’s rest?” I call. Silence greets me. Yao is probably stuck in his head and nature. Even I’m drawn by the geometrically patterned leaves and flowers here maybe more so if I could catch my breath. Yao stops at the bottom of a boulder, drops his bags to the ground, and pulls out his trestle and frame. He sets it on a steep slant on the rock. When Yao works, he stitches so tightly you can make out each strand on whatever animal he decides to manifest the fur of a panda or feather vane of a crane. I can hardly see the needle in his hands, as though he mixes the silk threads with filaments of air. He divides one strand into twenty, sometimes thirty strands, spreading out the colors gradually and softly.

I catch up to him and look over his shoulder where he splits a green strand of silk into threads so thin I can only see them because of the translucent-white backdrop. He faces an osmanthus at the side of our path, its bloomed yellow flowers like tiny suns decorating the mountain.

“At this rate, the Collector will catch up to us,” I say.

“You wanted to rest,” Yao replies.

“Not for an eternity.” The single osmanthus will turn into a forest of embroidered osmanthus and begonias, a several-hour endeavor at the least.

“You should go on ahead. You’re slower anyway.”

I watch Yao work for another few minutes before leaving him behind. I know I’m the bottleneck, and Yao can catch up no matter how long he lags. He has always been efficient and thinks all steps out ahead of time. Plus I slow exponentially with the upward slope while he speeds up so long as there’s an interesting shrub ahead of him.

As it darkens, I set my bags down on a soft patch of grass in an open area, far from ponds or dense forests where the tigers and snakes often roam. Yao should make it here soon, and likely not a single beat out of breath.

The next morning, Yao is not here. I retrace my steps, taking the treacherous hike downhill where the dirt is loose and slippery. I reach for one tree branch at a time to maintain my balance, poking and scraping my hands on the scraggly bark. When I arrive at the spot Yao had stopped to embroider, I instead find the Collector standing over Yao’s wood frame, supporting

rack, and a pile of tangled thread. I outstretch my arms to him, presenting my hands, palms facing upward, hoping my hands might quell his hunger. Instead of taking my hands, the Collector turns from me and descends the mountain. As the Collector’s black, cloaked mass drifts away like smog sinking with its density, Yao’s form is unveiled from beneath the tendrils. Yao’s hands are gone, but he holds his needle between his teeth. I pull the needle from his mouth and help him up.

“Can you pack away the chassis and fabrics?” Yao asks. “You’ll need to carry them too.”

I nod and fold the structure. “I’m going to be slow going uphill with all this extra weight.”

“That’s ok. There’s no hurry. The Collector shouldn’t be coming after us for a while.”

We continue back up the mountain, although Yao trails behind even though he should be lighter than ever.

Harvest and Holy

We are the earring collectors. We are goblins. We are hungry. We are queer.

Our most recent pair are stained glass windows. A wooden frame with thin colorful glass on the back. They’re on the heavier side but when they catch the light just right they’re worth the slight ache in the earlobes.

“I like your earrings,” is probably the most common greeting we get whether it’s on TikTok or waiting in line at the coffee shop.

There is no accessory more symbolic of our gender. Our collections are eclectic, ranging from handbeaded barn owls to sets our partners made from testosterone vials.

We laugh at the question, “Which ear is the gay ear?” The correct answer, “All of them.”

Late at night, we ravenously click on a small business's promoted post of Mothman earrings. We forget we order them and when they arrive we rejoice.

Greedy, we will make whatever we can find into something wearable. Dollhouse food miniatures and our exes fingernails and tiny jars of jam.

We are the keepers. We are the chain link fence back to our gold-earringed ancestors. Back to a needle heated over a flame before piercing skin.

Our flesh asks for more. Asks to hang on. Asks for burial jewelry and bridal pearls. Asks for picture frames and the smallest possible figurine of a dog.

Remembers the clip-on days. Remembers what it was like to first hammer a nail into the wall of a room we knit of our own hair.

Elegant and gaudy. Profane and sincere. We pick up shards of necklaces off the subway floor. We take orphaned earrings to lost and founds, saying, in vain, “Someone might come looking for this.”

We are not sure if we are dragons or angels. We are not sure sometimes what draws us to shape or design but we know we want to be remembered.

A few will stretch our ears wide. Scream into that opening. Place a plug there. A stopped drain at the bottom of a lake.

Often we are told we are too much. In loving ways and painful ways. Our bodies are turned into catalogs and museum gift shops. Our glitter, gulped down too fast. Some of us are eaten. Others, let the hole close. Say, occasionally, “I used to wear earrings.”

Some of us pile our hoards in old jewelry boxes. Some of us hang our lives neatly in a grid on the wall. Share earrings with lovers or say, “These are all mine.”

Our culture is one of harvest and holy. Of reused pickle jars and first dates on the moon. Kissing in the backseat of a car and saying, “Wait, I have to take out my earrings.” Earrings on end tables. Lost in passenger seats. Held onto by the other party, unwearable in their loneliness.

We do not ask what they will think when, in hundreds of years, they try to make sense of what we wore. We already know. We know they will say, “I want to make something, just like that.”

THE DISSOLUTION OF EVERYTHING BUT A RAKE

Not a damn thing happens in this story, just so you know.

My neighbor, Andrew, my athletic, decades-long friend, is out in his backyard preparing to rake leaves. He will never get them raked.

From my spot kneeling on the living room couch looking out through the slats of halfopen blinds, I’ve been drinking coffee and studying him for an hour. Though he stands tall and too thin atop the bank that overlooks my yard, he can’t see me. The sun has risen to just above my roof. His hand is flat over his eyebrows. Behind him waits the huge, old, beautiful tree with small leaves that spiral as they make their way to the ground.

Here's his problem: it is not autumn. It’s a humid as fuck summer day in the South where you’d only go out if you had to. Hot wind rustles the silvery green leaves in his tree. Andrew wears an insulated maroon jacket, jeans, and gloves that don’t match as he has journeyed to and from that tree over and over with a variety of tools and such.

My friend, the once quarterback, appeared first with a ladies’ field hockey stick, swinging it through the air, whacking at some weeds, setting it against a boulder, then heading back around his house to his garage. Next, he brought something three-pronged over his shoulder. Then a black plastic lawn rake. And more. He’s leaned them around the trunk like armaments at the ready. The man who once lined up stuffed bags of leaves like an offensive line between him and the street doesn’t know what to do.

Action? His head swings right toward a rushing noise, and he follows a car that passes by. For a second, he looks as if he will chase after it.

Jeanie, his wife, comes out now, calls and waves him to come inside. No way to know how long she has been looking for him. Sometimes she lets him wander so she can have a break. I know because a man one street over has brought him home twice when he got lost.

Andrew’s quick turn from her suggests he is resolute that this yardwork must be done, but she is still yelling, so he looks at her again, then rearranges his tools under the tree. She gets the hose to water shrubs and fill the bird bath so she can keep an eye on him while he strategizes the leaves.

I should go out. I won’t. Several times I’ve helped him back home when he thought he lived at my house.

Once, after he rolled his garbage bin three houses up the street to a lawn service truck he thought would take his trash, I ran after him. The mowers, who didn’t speak English, stood with their silent weedwhackers, looking to me in confusion. I carried his trash to my bin so he could roll his empty one home. Jeanie pulled up next to me, crying. She had driven the wrong way looking for him. “What am I going to do?” she asked me. I put my hand on her arm on the steering wheel with pity, not compassion. She, whom he has lived with so separately, has inherited his total care.

Andrew is nearly erased. Age, diabetes, a stroke and the Presbyterian church have all ganged up on his brain so quickly that I had to stop him at a recent gathering when he started telling a story about the man whose life we were celebrating. He made himself the hero of a game that never took place. In front of gathered guests, I whispered in his ear to stop.

Good neighbor me.

But I am not the friend I once was either. I resent Andrew. Oh, I miss going with him to a bar for chicken fingers and beer or getting up close at the free downtown concerts to watch the

guitarist’s fingers or comparing notes on a stupid investment we both made, which was my fault. My bitterness dwells in things that will never happen, the confrontations we will never have.

Jeanie gives up and goes in.

I want to rip into him about his political lurch of late, his repudiation of the generosity of spirit he had as a coach when he accepted everyone.

Since he’s been bragging in recent years about being “a sinner” as proof of his dedication to his church, I want to get into it with him about the affair he had twenty year ago, the one he’d triangulate as he regaled us with stories of New Orleans restaurants, of unwrapping muffulettas with her on the airplane, of standing with her in front of Lucinda Williams at a show in Florida, of watching the sun came up over the levee. He knew we would not tell Jeanie, that we loved his company and his shrugged misdeeds more than we liked his cold wife.

I want to ask him about Carl’s house that time when Becca, my wife, was getting her coat off the bed as he was coming out of the master bathroom, when he tried to embrace her. I tried to brush that aside for him. He needs to know that decision has plagued my marriage ever since.

But all he does is shift his shoulders toward Joan’s house across the street as if he has just thought of something. To make a run for it? To try to break coverage against the neighborhood’s soft prevent defense?

No. He takes the rake from its spot and holds it in the air in front of him with two hands, testing his grip. It is upside down.

His memory is like a football that’s been handed off to me to see where I can go with it. Anger doesn’t travel forward. I’ll quit. When I meet him, I’ll give him the candy -coated indifference we reserve for the helpless and those waiting for the right moment.

Shelby Mills is a San Marcos based artists whose work focuses on painting with inspirations from photography and abstraction. She uses electric colors and geometric environments to display themes of mental health, identity, and relationships. Her work has been shown at the Texas State Galleries, as well as Jo’s Café in San Marcos. She is currently working toward her BFA in Painting at Texas State University.

Adalyn Tâm An Ngô is a poet and writer of Little Saigon, California, currently in the mountains of Vietnam under a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Award. She recently graduated from Bowdoin College, where she received the Richard Jr. Poetry Prize (2021) and the Philip Henry Brown Prize for extemporaneous English composition (2023). She has also received the National Gold Medal in the Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards for Poetry.

Maria Pianelli Blair is a multidisciplinary artist born in New York City and based in New Jersey. A public relations director by day, Maria spends her nights dabbling in ceramics, printmaking, embroidery, and analog collage. Her collages, fashioned on everything from cardboard to playing cards, marry contemporary imagery, found vintage materials, and magical realism. Maria's work can be found on Instagram (@ sunset_sews) and Etsy. She has been published in several art magazines, and featured both galleries and virtual exhibitions.

Paddy Qiu is currently an MPH candidate at the Gillings School of Public Health. Their work focuses upon the navigation of spaces, emphasizing the conduits of knowledge found in generational ripples and the nurture of interpersonal relationships. They are the 2023 Winner of The William Herbert Memorial Poetry Contest with honors including The John F. Eberhardt Excellence in Writing Award, The C.L. Clark Writing Award for BIPOC Writers, and The Henry Matthew Weidner Essay Award, being featured in FOLIO, Barzakh Magazine, Zoetic Press, Quarter Press, among others

Michael Montlack is author of two poetry collections and editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva: 65 Gay Men on the Women Who Inspire Them (University of Wisconsin Press). His poems recently appeared in Prairie Schooner, North American Review, december, Poet Lore, Cincinnati Review, and phoebe. His prose has appeared in The Rumpus, Huffington Post and Advocate.com. In 2022 his poem won the Saints & Sinners Poetry Award (for LGBTQ writers).

Joseph Milne is an artist and filmmaker creating work that spans art nouveau pen and ink paintings, altars, projection art collages and surrealist films inspired by jungian psychology, the occult and psychedelia.

Alyson Miller teaches literature and writing at Deakin University, Australia.

Jonathan Jones lives and works in Rome where he teaches at John Cabot University. He has a PhD in literature from the University of Sapienza, and a novella ‘My Lovely Carthage’ published in the spring of 2020 from J. New Books.

Tiffany Promise (she/her) is a writer, poet, punk vocalist, chronic migraineur, and the mother of two wildlings. She holds an MFA from CalArts and has participated in the Tin House and American Short Fiction Workshops. Tiffany's debut chapbook, Blood is Thicker than Blood, will be available in 2025 from Chestnut Review. Winner of the 2023 Honeybee Prize for Literature—judged by Roxane Gay—Tiffany’s work has appeared/forthcoming in CALYX, Narrative Magazine, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, Epiphany, The Ocotillo Review, The Good Life Review, Okay Donkey and elsewhere. A lifelong horror fiend, Tiffany’s work skews gritty. Find her at tiffanypromise.com.

GJ Gillespie is a collage artist living in a 1928 farmhouse overlooking Oak Harbor on Whidbey Island, WA. A prolific artist with 20 awards to his name, his work has been exhibited in 63 shows and appeared in more than 130 publications. Beyond his studio practice, Gillespie channels his passion for art by running Leda Art Supply, a company specializing in premium sketchbooks. Whether conjuring vivid collage compositions or enabling other artists through exceptional tools, Gillespie remains dedicated to the transformative power of art.

Gia Bacchetta lives in Medford, Massachusetts. Originally from Sandy Springs, Georgia, she is pursuing a PhD in English at Tufts University. When not teaching, studying, and generally circling the vortex of academia, she enjoys dabbling in nonfiction and fiction writing. Her work is forthcoming in Trace Fossils Review

Lucy Zhang writes, codes, and watches anime. Her work has appeared in The Massachusetts Review, Wigleaf, Apex Magazine, and elsewhere. She is the author of the chapbooks HOLLOWED (Thirty West Publishing) and ABSORPTION (Harbor Review). Find her at https://lucyzhang.tech or on Twitter

Robert Bires writes in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He has published fiction and poetry most recently in Juste Literary, Piker Press, The Centrifictionist, and Sky Island Journal.

THE PANDEMIC-RESILIENT CITIES SCIENCE FICTION WRITING CONTEST

1ST PLACE - MARTHA HIPLEY

About 2,700 words

An Oral History of Flaviviridae tegumentum, as Told by Ana Merren, on the 10th Anniversary of the Publication of Cracked Screen

As far as I know I was one of the first infected here in Mexico City. It was near the end of January of that first year. Daniela and I had gone to a picnic in Chapultepec on a Saturday night, and we were both bitten to shreds. By Monday I was calling out of the contract job I had at the time to hang over the edge of my toilet the whole day, sometimes from one end, sometimes from the other, sometimes stretched from the toilet to the basin of the tub. By Friday I had lost 3 kilos from the nausea and vomiting and was subsisting on whatever drops of Electrolit would pass through my system between trips to the toilet. I had even switched from the zero calorie to the regular, desperate for the sugar I was already confident in my IUD- it was new since November- but this seemed to confirm more concretely that it wasn't a pregnancy In a dark little spot of my brain I felt glad to lose the weight of Christmas dinners and all the rosca de reyes, just before the tamales in February I could lie in bed and listen to music or a podcast or even walk outside for a bit, but more than a few moments at my desk and I was back to the toilet Daniela was fine

I made it into the study by pure chance. I was supposed to climb with Lore the following Saturday and had to cancel on her Her sister, the one that always seemed to be switching jobs, was doing administrative paperwork for some facility that was looking for people with just my strange symptoms Lore's sister pushed through my information to the top of the pile By Tuesday I was taking leave from my job, dropping off keys at a neighbor's, and taking the 1 line bus into Centro with just some track pants and t-shirts in my gym bag The one from [Sic] Club started to fall apart by the end, and I wondered if I'd ever get to go dancing again

The study had taken over one of those big beautiful buildings in Centro that was surely some kind of cursed colonial mansion Before hosting the study and after being the seat of some ministry of something it had been a pretty high-end hotel that had gone bankrupt during the pandemic. All the rooms were still nicely renovated with new plumbing so that you didn't even have to put the toilet paper in a bin, a real blessing given the nature of the virus. The hotel furniture had already been stripped out and sold, but the study had replaced it all with furniture that wasn't anything worse than what I had at home. The study's stipend for us guinea pigs was only a little less than what my contract had been paying, so if I hadn't felt like shit it would have felt like a real vacation.

My job had been paying in dollars, so I was pretty sure from the start that the study must be funded by some private entity, probably from the US, to be shelling out that kind of cash for participants, especially once I confirmed with the others that we were all receiving the same flat rate. You never know with these things, and you always have to ask It was a pretty solid sum even for the capital, especially if you weren't paying rent or buying your own food

We had anything we wanted to eat or drink besides alcohol, though most of us continued to lose weight at the start I missed drinking, but I almost never craved it because of the nausea They had to scale back the time we each were testing to an hour a day to keep our strength up More than an hour and no one ate at all

The testing varied but was structured in a tedious, self-important sort of way that screamed FAANG to me For the longest time, I was sure it was Apple wanting to hold onto their market share for smartphones, but Julio was set on Meta What's the good of the Metaverse if no one can put a screen to their eye anymore? Once we made the mosquito connection we were both pretty sure it had to be Microsoft

The test was always the same: an image of some generated landscape and then a passage of text from The Mysterious Island I had never read it, but I remembered enough from the Ray Harryhausen movie to recognize it We would have to look at the image, and then they would ask us to read the text aloud The text always changed, but it was always from The Mysterious Island and randomized so that you couldn't even enjoy the story. We would do this with as many devices as they could fit into the hour timeslot. By the end we all always felt awful, so they usually did it first thing in the morning so we would have enough time to recover and eat. Sometimes the devices would be this phone or that tablet, and sometimes they would be more experimental. Towards the end of the study they only used those half-baked things, sheets of floppy LEDs with power sources hanging off the backs, or bubbly things that seemed to be made of silicone. They all made everyone sick every morning.

The rest of our time was essentially free. The center of the building was carved out into a courtyard that had been done up with too many plants as the hotel's dining room. The hoteliers had left a certain amount of crumbling luxury from the colonialists, and all their half-abandoned landscaping had added to the romance Once I was feeling stronger I took to running laps around the edges and sunbathing in the middle Julio liked to hang out in the courtyard as well- that's how we started talking He would bring out a guitar and noodle around with it in the sun, and I would make fun of him every time I looped past

There was a side exit on the courtyard with wooden doors that were venerable enough to have a good three centimeter crack between them where I could look out into the downtown There was a little

newsstand where I could catch the fronts of the nota roja tabloids and people-watch. Julio would keep watch while playing We had a little cue he would play if he thought a nurse or watchman was getting close enough to scold me It never happened, but sometimes he would play the riff just to scare me I would stare for as long as I could before catching a glimpse of someone's phone in their hands, and then I would try to lock it all in my mind Then at night I would lay out on the floor of my room with pads and pencils and draw what I could remember

We could have anything else we wanted to do, and we could call out to friends and family with the help of a nurse At the beginning I didn't tell my family, though I called them often I told friends abroad as-needed Lore already knew and would bring me my favorite foods and gossip whenever I asked, usually about some guy in her office who had a new crush on her, and Daniela would bring her dog, who was a star amongst the nurses. Jorge snuck in a bottle of expensive gin once, but I got so sick I couldn't touch gin again for years. Once the drawings started to pile up, I called up Fer. Every month or so, whenever he was in the city for an installation or an opening, he would stop by and poke through them and pick out the ones he liked the best to whisk away from any nurse who might try to over-tidy.

The first person I told in the US was Michael. He was always easy to tell intimate things, but my reason was that he seemed so depressed from the New York weather. I wanted him to come use my apartment while it was vacant and get some sun. He flew down with an extra suitcase full of English novels for me I liked seeing all the little ways he had marked them up I always wanted him to write more, but he kept his data job with the bank for the first six months at least

Julio had trained to be an architect but was as happy to give that up in favor of doing nothing but playing his guitar as I was to make my drawings I have to admit he wasn't very good at first, or was at least very rusty, but he progressed from passable to enjoyable quite quickly Even when his playing was terrible, he had a good clear voice and was plenty charismatic It was easy for both of us, and for many of

our fellow patients. The only thing we might have worried about was the money, and that was already taken care of He never wanted to talk about the work before, but I assume it was like mine, hunched for hours, clicking through tabs and files

In those early days, the only one who really suffered and the only one to pass was Mafe She was younger, and was something of an influencer, or thought she was Someone told me later that she really never had that many followers, only a few thousand She would cry and scream and refuse to eat, and she even hit the nurses until one of them snuck her in a phone Or maybe it was her boyfriend For years I wondered how the technicians never even noticed that she was wasting away until I realized they probably just wanted to see if she would die

Around the time that Mafe died, Julio and I started sleeping together. I still had the IUD, and what else did we have to do in the evenings? I don't want it to sound perfunctory or boring. It was always good. We just never had to compete for time.

I was writing more as well, and felt like it was interesting enough to tuck it all under the mattress until Fer's visits. What he ended up sending to print wasn't really meant to be a manifesto, it was really just some journaling that he had edited to hell. After it was printed I was sure for weeks that I would be found out and booted, but no one from the study cared enough to pin it to me. By then there were maybe 100 of us in our facility, and however many more in other studies here in Mexico and around the world. I was always careful to make things vague enough

I know there's still all the weird theories, but I'm sure I got it from a bite that night at the park In the early phases there was some hope it might be something like Zika or malaria, confined to the tropics, easy to control by important people in the important parts of the world When it started to spread through sex, that was really the end of it There were little memoirs like mine, but also real books and speeches and marches Julio never wrote any music about it, but lots of people did Here in Mexico it was when the

mayor- married of course- finally got it that things started to shift. Even el PRI couldn't ignore it anymore. But it all added up, the way it always does, from the garbage cans on fire in Paris to the quiet legislation in Reykjavik The New Americans with Disabilities Act was the first thing I felt proud of coming out of my country in years Not proud enough to move back, but enough to have that sort of single patriotic tear that no one I knew seemed to have had since Obama first got elected

Of course there was bug chasing I don't have anything to say about the legal or the moral side of all the stealthing, there are other people you can talk to about that But I don't begrudge the chasing Once, when I was working in Manhattan, I got hit by a car biking to the office, and the best part about it was I didn't have to go to work The second best part was that the cab driver who hit me gave me all his cash from the day, and I took a friend out to dinner.

Anyway, after Anibal Casto got it and spent a month appearing on the mañenera trying to smooth things over with both his wife and the country while looking green thanks to the teleprompter, it all started to settle. Accommodations were made. I knew it was all over when I called Laura and she had it from a camping trip. She went out and bought a typewriter and called her agent to say she wouldn't be available via email anymore. That was it. She and John, they already didn't let their sons have screens, so I think it was just a relief for her to get to follow her own rules finally. We still had photographs, and movies, and the radio, and sports, and beaches. We're lucky here in the city with the Cineteca's archive of 35mm reels

Julio and I milked the study as long as we could We weren't in one of the ones trying to find a cure or a vaccine It wasn't anything invasive We were paid well, and the payments kept going for a while until the US Congress split up Microsoft and everyone got laid off from whatever department was authorizing our transfers By then we had long moved back to my place, with Michael still lingering on the couch He was writing again, and I came home to books stacked high against every wall in towers that

would spill with every little earthquake. Eventually I let Michael take over the place, and Julio and I found a new one together We had all the money saved from the study, and my paintings and drawings were finally selling well thanks to Fer Michael finally had to leave the stupid data job after catching the virus He still hasn't finished a novel, but he's had some stories published

Every crisis is someone's terrible opportunity, and we were able to buy a little place in the city with the money we had saved from the study and the international sales of the book I think Fer lost money on the Mexican edition, but he's made more than enough back from selling the original drawings

It's big enough for me and Julio to have space to work, and for our families to visit, and for Zuzu to have her own room eventually She never got the virus It's not congenital, contrary to popular belief Maybe she'll get it some day, but she's grown up only knowing how easy it can be. People do take the vaccine here, but mostly if they are interested in the screened careers, which always pay well because no one wants them. It's a good way to stay out of debt, I guess.

Last weekend we took the bus to La Merced. Zuzu had earned whatever she wanted from the sweets market for being brave and learning to ride her bike. She only fell twice and didn't cry at all. After she had pointed and picked and filled up a sack with sugar and coconut (she's so particular), we walked to Sonora, through all the incense and candles and back to the shrine to Nuestra Dama de los Mosquitos. It appeared a few years ago, a little cult to all the sex workers, mostly women, who had offered their services to those who wanted to choose in those early days I remember them splashed out in that horrible red on the covers of the nota roja I could see through my little golden prison I lit 3 little candles, and Zuzu left a little marzipan flower I don't believe in God, but I do believe we're lucky

THE PANDEMIC-RESILIENT CITIES SCIENCE FICTION WRITING CONTEST

2ND PLACE – SCOTT BATSON

The Sky Never Changes

Yifan shuffled forward with the line, her daughter’s hand squeezed in the sweaty mess of her palm, and wondered if she should feel guilty for risking the lives of the three hundred people around her. For the hundredth time, she debated leaving the line, sacrificing her entire life’s savings and avoiding the risk of being erased. There’s no turning back, she told herself. And what were the lives of three hundred strangers against the life of her daughter?

With her free hand, she flipped the corner of the ID she’d been provided, the laminate chipping away. Elizabeth Olmsford, the ID read. Yifan repeated the name again and again. Elizabeth Olmsford. Elizabeth Olmsford. The name felt so foreign, so unfitting. They will see right through this, she thought. I don’t look like an Elizabeth.

The taped arrows on the ground guiding Yifan and her daughter to the check-in station were scuffed torn up by the hundreds of feet that walked over them every day. They’d been in

line for hours already, broad blisters forming in the shoes she’d been provided.

“Can we go home soon?” Madeline, Yifan’s daughter, asked.

“Soon, sweetpea.” Home was so close. Home was a lifetime away. Only a three-mile walk to the place where Madeline had been born. Three miles and sixty years.

The check-in center housed two dozen kiosks, separated by large black, stone columns and a slabbed roof that stretched over them all, making it look like a giant comb. In her time, it was still a park. She took her daughter there for softball practice in the spring, where they sometimes played under the buzz of the lights. She and her husband used to watch lightning bugs in that same park when they were teenagers, his arm wrapped around her as he struck up a cigarette with the other. “Those things will kill you,” she used to say.

If only that was all they had to worry about.

A sign above one of the check-in kiosks spelled out a warning in bright, reflective letters: TIME JUMPERS PUT US ALL AT RISK.

For a moment, she thought the sign was meant just for her. YOU PUT EVERYONE HERE AT RISK, Yifan. But she blinked and the sign went back to normal. She focused on the head of the person in front of her instead a bobbing tangle of gray hair as the old man shifted from foot to foot.

Apollo had told her the kiosks never close, but most people arrived toward the end of the work day. If Yifan wanted to blend in, her best chance was to wait in line with the biggest mass of people.

Is Apollo even his real name? He couldn’t have been more than eighteen years old. I don’t look like an Elizabeth; he certainly didn’t look like an Apollo. Maybe it was better if she didn’t know his real name. The ignorant betray very little, after all. What do I care? If I’m

caught, I’m dead. She straightened and squeezed her daughter’s hand. Dead wasn’t the right word. She’d be erased; ripped from time, left in the space in between, and obliterated from existence.

Death was staying in her time. Death was doing nothing. Yifan had watched behind barred windows as death took her community.

“Mom,” Madeline whispered. “These clothes are itchy.”

“I know, sweetpea,” Yifan whispered back. She could feel the eyes from the man behind her his ears were probably clued in too. “It won’t be much longer.”

Apollo had given them the clothes after they made the jump. “This is more akin to the fashion of this time,” he told them. Soft, pastel colors and hard, thick linen cloth. It was like something she saw her great-grandmother wear before she passed away. Funny how fashion was like that, repeating itself across generations.

The man behind her cleared his throat. The line moved again, so Yifan took a step to the next marker and Madeline kept close, without much prompting. Luckily, she’s shy. Yifan thought. She had been a chatterbox herself when she was a kid and Madeline’s father had a habit of always sharing his mind. But somehow, they had made a beautiful, smart girl who shied away from strangers.

JUMPERS BROUGHT US THE DEEP, another sign read neon letters flashing in the hazy afternoon light.

She kept trying to steer the thoughts away from her husband but even in her mind, he was stubborn. Would he still be alive when they got back? Or would he waste away, alone and afraid, locked in their garage where she had left him? She could still hear his voice through the front door after she had barred it.

“What are you doing? It’s me!” He’d shouted, pounding against the deadbolted door, his voice ragged and foreign.

The way he gawked at his hands through the cracks in the window, bluing skin like the deep ocean and veins as dark as midnight coming to the surface like webbing. He punched the door and screamed at her when he tried to walk into the house they had lived in together for eight years the house where they raised their daughter.

He’d only gone out to get groceries. Just fruit and milk. The tragic thing was they hadn’t really needed any of it. After months of being cramped together, Yifan had just wanted a few moments of quiet as Madeline napped. A few brief moments where she could lay down with her eyes closed and try to forget the world was ending. So she’d sent him out to get groceries.

“I’d rather stay in until the next dropoff,” he’d said.

“We need fucking milk,” Yifan had snapped back.

She’d never even picked up the milk and fruit he’d dropped on their front porch. They were probably still out there, rotting and stinking up the floorboards.

Yifan had expected grief to wash over her, but it’d been mostly anger. At herself for sending him out, at her husband for being careless, and at the city for not better controlling it. And now here she was, jumping through time despite all the warnings.

“Keep moving,” the man behind her muttered. How had the line gotten away from her like that? She kept Madeline close, pressed against her hip, and for whatever reason, the kid never complained about her hand being crushed.

“How much longer?” Madeline asked.

“Not much longer,” Yifan lied. She had no idea. The first stop was the check-in station, where they would check the fake IDs Apollo had provided.

“Is Dad coming?” The question was a punch in the gut.

“No, sweetpea.” Could Yifan look up his name on the datapad Apollo supplied...

“Next.” The man at the check-in counter waved Yifan forward, the people in front of her vanishing into the building behind the Comb. He sat behind a few inches of plexiglass, stationed at a metal desk that matched the cold, solemn aesthetic of the building.

A small drawer came out from the wall. “Place your IDs in the drawer,” the man behind the glass said, his voice tinny through the intercom. Yifan’s hand shook as she put the counterfeit IDs in and smiled. She fought the urge to fill the tension with questions.

He held up the ID and looked between it and Yifan. “You look familiar. I know you?” he said, stroking his stubble.

“Just one of those faces.”

“You live up in Brighton?”

Yifan shook her head. “Watertown.” Just like the ID said. But she had lived in Brighton. Sixty years before now.

She glanced down at the placard at the front of his desk. “AJAX BELLAMY” was printed in all capitals and her mouth went dry. What are the odds? Of all the lines she could have selected, she ended up at the one manned by Ajax Bellamy, a boy from Madeline’s class who had lived up the street.

It was impossible to translate an eight-year-old boy into the old man she saw in front of her. He was lanky now, with wiry arms too long for his shirt sleeves. But as a boy, he was always the runt on the street chubby and slow, peddling up the block on a bike that was too big for him. He still had the round face, though, and the wide, curious eyes although the bags under them made his whole face look solemn now.

He scanned the IDs through some machine and when the green light came on, Yifan let herself breathe. “You’re all set,” he said and put the IDs down in the drawer. Before he pushed them back through to her, he bit his lower lip, the same way he did as a kid when he was working out a puzzle. “I swear I’ve seen you around. You work in Quincy Market?”

Yifan had worked as a medical assistant before the world shut down but the last year had been nothing but watching her daughter and worrying that every passerby was infected. “No,” she told him.

“It’ll come to me,” he said and slid the IDs back. Hopefully, it wouldn’t come to him until she was long gone.“Just follow the line to your right there and wait for your number to be called.” He eyed her as he reached for a button that opened the metal gate and lit her way forward.

Yifan collected the IDs and scurried inside, away from the one person who may actually recognize her before his memory caught up. Bad luck seemed to be the only luck she had lately.

The waiting room was a long hall of humming, fluorescent lights, and propaganda posters about time jumpers. Yifan took a small bench for her and Madeline, pressed against the rear wall and away from people.

“Now serving number B-two-thirty-nine at counter six,” a monotone voice said through the loudspeaker. Yifan double-checked her number the paper already crinkled. C-103.

With time to waste, Yifan took out the datapad Apollo had provided a thin, flexible tablet that had most of the controls disabled.

“Remember, we’re watching,” he had told her when they were making their way from the

jump spot. “So you can’t go looking for anything to extort the time jump. No winning lottery numbers or anything like that. But it has the relevant information you’ll need to study.”

She’d only been in this time for a day but she was expected to cram 60 years’ worth of major events into her head. In school, she had avoided studying copying off of friends or getting help with papers. Reading through mountains of text always put her to sleep, so she had to pinch her leg to stay focused. She’d learn as much as she could so Madeline had a future. She’d do anything so she could hug her husband one more time.

“The agents inside, the ones who administer the shots, they know to look for jumpers,” Apollo had explained. “Your ID gets you in the door but you still have to convince the agent you are who you say you are. They’ll ask questions about your birthplace, hometown, parents, and more. Any data they can find publicly. That’s all there in the datapad.” He tapped it with two fingers, holding eye contact with Yifan.

“But they will ask you about current events too. Things anyone should know. Who’s the President, what’s the price of gas, stuff like that. It’s ok if you stumble. People naturally stumble. But they will try to throw in a trick question. Like ‘Who won the Super Bowl?’ There’s no NFL anymore.”

So Yifan studied, doing her best to read over the general facts of the past sixty years. The Super Bowl question she could have guessed. She remembered when the stadiums started shutting down, leaving a season half-finished. That was the first time she realized the Deep was something to be worried about, something more than a problem on television.

“Now serving number B-two-forty at counter twelve.”

The hall curved and stretched on forever, with different markers for the different counters. Over half the world died to this and they still have lines this long? Yifan thought but

then remembered she and Madeline were two extra people added to the queue. No wonder they knew to look out for time jumpers they’d probably given out more shots than they estimated.

Or was Elizabeth Olmsford a real person who would never get her dose because Yifan had shelled out every penny to her name to secure a spot?

It doesn’t matter, Yifan told herself. If she’d trade the lives of those three hundred strangers waiting in line with her, then she sure as hell would give up Elizabeth from Watertown.

Anything for her daughter.

“Now serving number C-one-zero-three at counter fourteen.”

Her mind was stuck in the datapad, her attention divided. She wasn’t quite certain it had been the right number. When no one else got up, she nudged Madeline awake and clicked off the datapad.

“C’mon. We’re almost done.”

Madeline sighed. “Thank god.”

Yifan took her daughter’s hand and guided her up the hall. It reminded her of running through airports, trying to find the monitor to see if your gate had changed, scrambling past white walls that all looked the same.

Finally, she found a sign for counters one through fifteen. Another hall, another turn, and another array of dizzying fluorescent lights showed the way to another impersonal station. At counter fourteen, behind more plexiglass, was a middle-aged woman with thin-rimmed glasses, manicured eyebrows, and a shade of lipstick that was a bit too dark for her complexion.

“You can have a seat right there.” The woman motioned to the two chairs on the other end of the glass. “And just place your IDs in the drawer.” Yifan’s smile did nothing to disarm the

woman as she followed the instructions. The woman scanned the ID and said, “How are you doing today, Elizabeth?”

“I’m fine. Yourself?”

“Not bad. Getting close to the end of the day.” She looked at her screen as she talked, typing like a pianist. “As you probably know, I do need to confirm your identity and ask a few questions.”

Yifan’s heart felt like it would jump up her throat. She pinched the inside of her thigh, hoping the pain would keep her from shaking.

“Where were you born?” the woman asked, her voice muffled through the glass.

“Stoughton.”

“And where did you grow up?”

Yifan had memorized all of this early on Apollo had made her recite the basics before they even made the jump. “Berkeley when I was young, but I don’t remember it. Amesbury after that.”

“When did you get married?”

“June fourteenth. Twenty-one, ninety-three.” That one was easy to remember. Madeline’s half-birthday.

“Where was the reception?”

A trick question already? “The what?” Yifan acted dumb.

“Nevermind. Who is the current President?”

Yifan raised an eyebrow, acting the part. Although Apollo had prepared her for these questions, he had hammered home the point that most people of that time didn’t expect them. They would think: what the hell does this have to do with me?

“I’m sorry?”

“Who is the current President?” The woman repeated.

“Miller, unfortunately.” Yifan grimaced but the woman wouldn’t yield even the slightest smile.

“How many states are in the Union?”

“Twenty-three.” That was a part of her future she wished she could read more about but there had been only so much time to cram.

“Who is the Surgeon General?”

Yifan wouldn’t have been able to name the Surgeon General of her own time, but given the health crises, the position had become glorified or so she read. It was a position more touted than the President. “Regina Keefner.”

“Who won the World Series last year?”

This one felt like a trick like Apollo’s Super Bowl example but Yifan had managed to skim this one bit of relevant news. The previous year had been the first season in several decades with a full baseball season, although there were only eight teams. It had become a cultural phenomenon. Even if you didn’t like sports, her datapad read, people tuned in to watch the World Series.

“The Orioles.”

The woman finally smiled. It was an awkward slant of her mouth that didn’t match her eyes. “Glad that’s over with. Thank you for your patience.” She slid their IDs back through the drawer and opened it with a flick of a switch. “Are you both receiving the shots today?”

Yifan took a calming breath as she reached for the IDs, her hand shaking like she’d downed a full pot of coffee. It was really over. She just had to smile, accept the inoculation, and

be on her way to her century, her daughter safe.

“Yes… yes, both of us.” She smiled down at Madeline, who didn’t seem vexed in the least.

“Your daughter is so patient. Most kids we get through here are complaining by the time they make it to the counter.”

“She’s always been pretty calm. She must get it from her father.” Yifan chuckled, reveling in the honest bit of dialogue. It was the first moment she had felt normal since arriving in the future.

“What grade is she in?”

“Third grade.” The schools had gone remote in her time, and the curriculum was fractured, suffering from a lack of staffing. Still, it was better than nothing.

The woman behind the counter pulled open a drawer and fumbled around inside for a moment. “It looks like I’m out of needles,” she said, her hands still sifting through whatever was tucked away, out of sight from Yifan’s gaze. “I’m just gonna go grab a few. One second.” She swiveled in her chair, stood, and walked back into the room of desks, cabinets, and medical coolers.

Yifan couldn’t see much past the first rows of desks, so she leaned back in her chair.

“Are we almost done?” Madeline whispered.

“Just about, sweetpea.” Yifan was almost giddy. There was still the ordeal of getting back to the jump point without being noticed, but there didn’t seem to be a ton of security on the street. This was the hard part. The final wall to scale before making it to the Promised Land.

But the woman still wasn’t back. How long does it take to grab a couple of needles? Maybe there was more to it than that. Apollo said supplies were extremely limited. It’s not like

they would just be sitting in a bin. There was probably a process for requisitioning them, some papers to fill out. The place reeked of bureaucracy… So much, in fact, that each station should already have the exact amount they needed.

Right?

Was that something she could look up on the datapad? Yifan flicked it back on and started skimming articles. Had she missed something? Every question was expected. She had answered them all perfectly. Unless her data was wrong. How would she know? Would Apollo have given her faulty data? Or was it that… Shit.

Yifan jumped to the index, skimming topics until she found one she had skipped over. Education. She tried to read through the bullet points but her pulse was hammering behind her eyes and she couldn’t make sense of the words.

School for children has been restructured to a tiered system based on merits and not aligned with age. Each subject has its own tier, therefore, and students become more proficient in different subjects at different rates. Due to remote access, schools had to…

The words started to jumble in her head, so she flicked the datapad off, her mouth cotton and her arms shaking. There was no ‘third grade’ anymore. There hadn’t been grades in four decades.

“We’re going,” Yifan told her daughter, motioning for her to stand up.

“Now?”

“Yup.” She took Madeline’s hand, pulling the child up and out of the chair and exiting the cubicle in one motion. She followed the arrows, working toward the exit.

I was so close. The pulsing behind her eyes turned to tears. She bit her lip to hold them

back, resolved to at least make it outside.

The hall stretched on forever neon arrows of yellow tape shining under the hum of the fluorescent lights. There was no nook to hide in, no corner to cry behind. Finally, the exit sign appeared, hung over a turnstile with a guard standing duty. He eyed her as she rushed down the hallway with Madeline in tow.

“Do you have your card?” the guard asked, his voice rough as gravel.

A card, showing that she had been inoculated. A card she had been moments away from getting.

“My card?” She smiled, playing dumb.

“Your inoculation card. Should’ve got one right after the shot,” the guard said.

“They must’ve forgotten.”

The guard rolled his eyes. “It happens. That’s fine. I can walk you back to get it.” He started forward, motioning with his head for her to turn around, his hand on the baton that hung from his hip. “What station were you at?”

“I… I don’t remember.” She lied. C-one-zero-three at counter fourteen. That number would be etched into her mind, like a date on her tombstone.

“I can just check at the terminal.” How long before someone called through to this guard’s radio? How long before shouts came from up the hallway and a rush of men spilled out from the doors to whisk her and Madeline off to oblivion?

Erasure.

“What’s the last name?” the guard asked as he tapped a touch screen on the wall. Could she just run for it? If she picked up Madeline and sprinted toward the exit, could she make it before this oaf even knew what was happening?

“There you are.” A voice came from up the hall. “I was looking for you.”

The guard looked to the man up the hallway and then back to Yifan. “She one of yours?”

“Yes.” It was Ajax the round-faced boy from her street who had grown into a tired, round-faced man. “I forgot to give you your card. Sorry about that.” He handed her a laminated piece of cardboard, no bigger than a playing card, imprinted with the name on her fake ID and a seal she didn’t recognize. Behind it, a slip of paper, torn and jagged.

“Okay.” The guard shrugged, leading them back to the exit. Once he was ahead of her, Yifan took out the slip of paper and read the note Ajax left:

Meet at corner of Milk and Congress.

“I knew I recognized you,” Ajax began, sweat dripping down his round cheeks. “It kept bugging me and my memory ain’t what it used to be. But you remember people from that time.

From the early days of all this.” He looked at Madeline a girl technically his age but he didn’t say anything to her. “We’re told to keep a lookout for jumpers. It didn’t click for me until my shift ended, and I realized who you were.”

“Why were you in the building though?” Yifan asked, holding Madeline close as people passed by on the street, going about their day like death wasn’t looming around every corner.

“I heard the call on the radio when I was at my locker. Your admin figured it out and was calling it in. They were just waiting for a squad to show up. Good thing you made a break for it when you did.” He laughed like it was a clever joke but all Yifan wanted to do was vomit on the sidewalk. She bit her lip, taking deep breaths through her nose, urging her heart to slow down. How close was she to being erased? Would her husband ever know what happened to her and their daughter?

She looked up at the darkening sky, holding back tears that had been trying to break free for the past hour. Dark, gluttonous clouds threatened the city as a wind rushed through the streets, cutting through the cheap clothes Apollo had provided. That feeling of chill that kissed her skin reminded her of her husband and the way they would sit out on their front stoop and watch the rain pour in the street in the summer. Would he even be there when they got back?

“Anyway,” Ajax said. “I’m glad I found you. I know they warn us against jumpers, but I figured they wouldn’t do that unless some got through already. And I thought it can’t be all bad, letting a few people live long lives. Even if jumpers caused the Deep in the first place, it can’t really unravel all this,” he motioned to the city, to the people, to the time.

He reached into his coat pocket and pulled out an envelope. “I want you to take this.”

She held out her free hand, Madeline still gripping the other and took the bulky envelope without much thought. “What… what is it?”

“A vial. Good for two shots. One for each of you. You’ll have to find your own needles, though. It goes right into the shoulder, right in the muscle. No wrong spot as long as it goes in.”

Shots? The word almost had no meaning as she ran it over in her head. Shots.

“Your arms might be sore for a few days. Might even come down with a fever, but don’t worry. Even if you got the Deep already, it’ll cure ‘em. Can bring you back from the brink, even.”

“Why would you do this?” She asked, pulling the envelope closer to her chest, closer to her heart. There was something else in there padding around the vial.

“There’s a note in there… I want you… I need you to give it to me… Kid me. And I don’t want you to read it. You have to promise not to read it.”

“I promise.” A note? From his future self? Apollo had warned about bringing anything

back. They couldn’t even have the clothes he’d loaned them when they made the jump. Just their underwear, apparently.

“They search us before we make the jump. I can’t hide something like this.” If she couldn’t pay the price he was asking, would he take it back? Should she run now while she still has legs under her?

“They don’t do cavity searches,” Ajax said and Yifan took his meaning. Anything for my daughter.

Yifan just nodded again, muted sunlight vanishing even more behind the horizon of dark clouds. “Won’t you get in trouble? Would they erase you for this?”

He nodded. “Yeah, most likely. That’s why I need you to get that note back to me. It should set me on a different path. It should save me now The old me.”

She understood. He was breaking the law for a better life, betting that he’d never have to ante up. Like when you swear someone out on vacation. And when your husband tries to admonish you, you just say “What? We’ll never see these people again.”

“I have to go,” Ajax said, checking his watch. “You can’t stick around long. They know your face now and will be on the lookout, even outside the facility.” He tapped his shoulder with two fingers. “Remember: right in the shoulder.”

She nodded her thanks, holding the envelope to her chest as Ajax made his way back into the busy street. Rain started to trickle down, drumming against the sidewalk and street lights of the city. A city she’d always known. A city that was completely foreign to her. I should probably get inside. But her feet wouldn’t move. Instead, she let the rainwater rush down her face, mixing with the tears she couldn’t hold back. Tears of relief, tears of terror, tears for her husband. A slow rumble of thunder sounded in the distance but she still couldn’t bring herself to move. She

just sobbed, staring at the sky as passersby moved around her like she were a stone in a river.

Yifan sipped her tea ginger and lemon stoking the fire she had started in the living room. Madeline laughed behind her, doing a puzzle with Ajax. It was the first time they’d had anyone over to the house since the whole thing started. Yifan hadn’t known that Ajax was usually left alone while both of his parents went to work, riding his bike up and down the street until they rolled home close to midnight.

She’d never have thought of inviting him in before, but knowing that Madeline wouldn’t get sick, it seemed like the right thing to do. Hell, it was the least she could do, all things considered.

Yifan leaned back in her chair and warmed her feet by the fire, staring out the window at another darkening sky just like the one she’d stood under before making the jump back. As different as the city had been, it was comforting to look up and know that the sky never changes and the stars you grew up watching would still be there long after you were gone. A few stars poked as the city lights died and power was shut off on the street, breaking through a blanket sky a shade of midnight the color of the Deep.

“Feeling okay?” Her husband asked as he came in from the kitchen to join her. Only three days and his skin had gone back to normal, his voice had returned and he was upright. Old Ajax had been right that shot could bring someone back from the brink.

Yifan had tried to give Madeline her shot as soon as she got home a medically sealed needle in her supply closet from before she’d lost her job. When Yifan rolled up her daughter’s sleeve, Madeline stopped her. “What about Dad?” She asked, her eyes wide and pleading. How was it so easy for that girl to know the right thing to do? There was so much good in that girl and

Yifan would do anything to preserve it.

So Yifan never got her shot and maybe that meant that she wouldn’t get to see her daughter grow up. But wasn’t that always the risk? Wasn’t that the ultimate risk of being a parent?

Ajax laughed as he held up a new piece of the puzzle. “I found the other corner!” A kid with a goofy laugh who would grow up to be a tired but brave old man.

“You want to help us, Mom?” Madeline asked.

There was nothing she wanted more in the world. “Yeah, sweetpea.” And when she got up, she tossed the note from Old Ajax into the fire. If his life changed for the better, would he be there in the future to sneak her those shots? She couldn’t take that risk. The chance of that note unraveling everything, leading to a life where he wouldn’t be there for Yifan and her daughter?

Anything for her daughter.

THE PANDEMIC-RESILIENT CITIES SCIENCE FICTION WRITING CONTEST