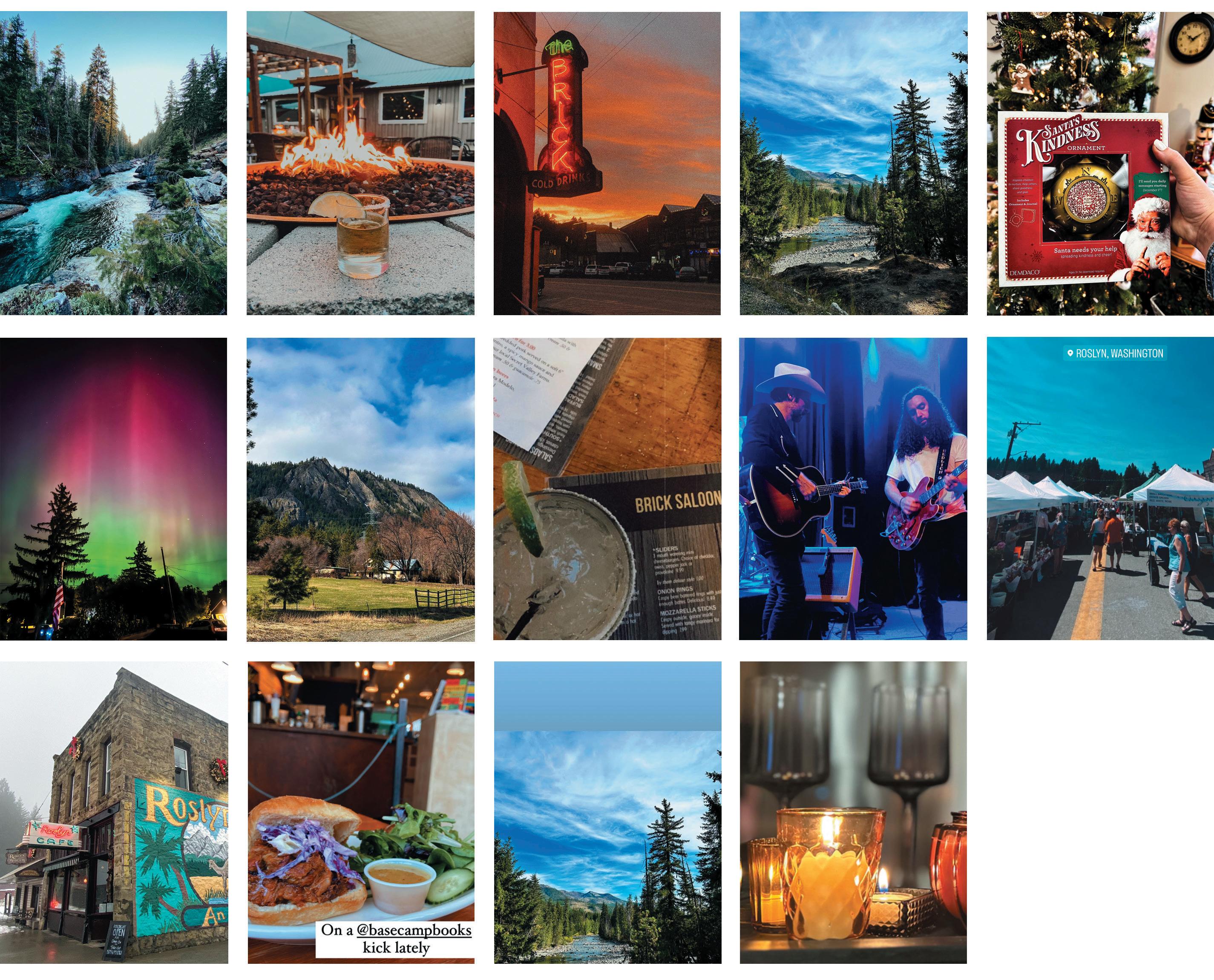

For Kittitas County resident Chelsea Stalder photography has been a lifelong passion. She picked up her first camera at just 8-years-old, sparking a creative journey that has grown into a vibrant way to connect with her community.

Stalder’s love for photography intertwined with her professional life while working as an event coordinator at Heritage Distilling Company in Roslyn. Surrounded by local businesses, rich history and the charm of Roslyn, she realized she could capture more than just moments — she could capture the spirit of a town.

That idea blossomed into Experience Roslyn WA, an Instagram account dedicated to highlighting the beauty, businesses and people of Upper Kittitas

County. From Elk Heights to Ronald and beyond, Stalder uses her lens to shine a light on the unique stories that make the community special.

“I wanted to create a space where locals and visitors alike could see what makes this area so incredible,” Stalder said. “Roslyn has so much history, character, and creativity — and every business and street corner has its own story.”

Since its launch, Experience Roslyn WA has quickly gained attention as both a visual love letter to the region and a helpful guide for those looking to explore it. Stalder continues to combine her passion for photography with her devotion to supporting small businesses and sharing the heart of Roslyn with the world.

This month’s cover features several vintage photos that portray a significant part of Kittitas County history - coal miners. The black rock was found in abundance throughout northern Kittitas County and it brought people of many nationalities here to work the mines in search of a better life for themselves and their families. Many of their descendants still call these quaint towns home today.

— Photos courtesy of Washington Rural Heritage

September in Kittitas County carries its own rhythm. The mornings turn crisp, school doors swing open, rodeo memories still echo in the air and the land stretches out in shades of lightly burned butter. It’s a month that reminds us of where we’ve been and where we’re going, rooted in both tradition and change.

This September begins with an especially meaningful moment for our community: The Wall That Heals in Rotary Park. Standing before it you can’t help but feel the weight of history and the depth of sacrifice it honors. It’s a reminder of the lives given, the families forever changed and the gratitude we owe.

From reflection we move into celebration. We gather downtown for the traditions that fill our streets with life—Bite of the ‘Burg and Buskers in the Burg—where food, music, art and talent bring neighbors together in the kind of joy that makes this county so special.

Inside this issue you’ll discover stories that speak to

the strength and character of our communities, past and present. We visit the Roslyn Miners Wall, a lasting tribute to those who built lives and futures in this valley’s rugged hills. We share the legacies of the Craven and Donaldson families, whose roots and contributions remind us how much individual families shape the larger story of Kittitas County. And, a story about the humans and non-humans who dedicate their lives in rescuing others. As always, you’ll find even more voices, events and moments that make this place shine.

As 1883 heads into another autumn, I remain grateful for your response to our passion, stories, for your traditions and for the way this community continues to inspire us month after month. Thank you for allowing us to reflect, celebrate and share alongside you.

Robyn Smith, Publisher

Andrea

Paris, Editor/Designer

Contact us at editor1883kittitascounty@gmail.com

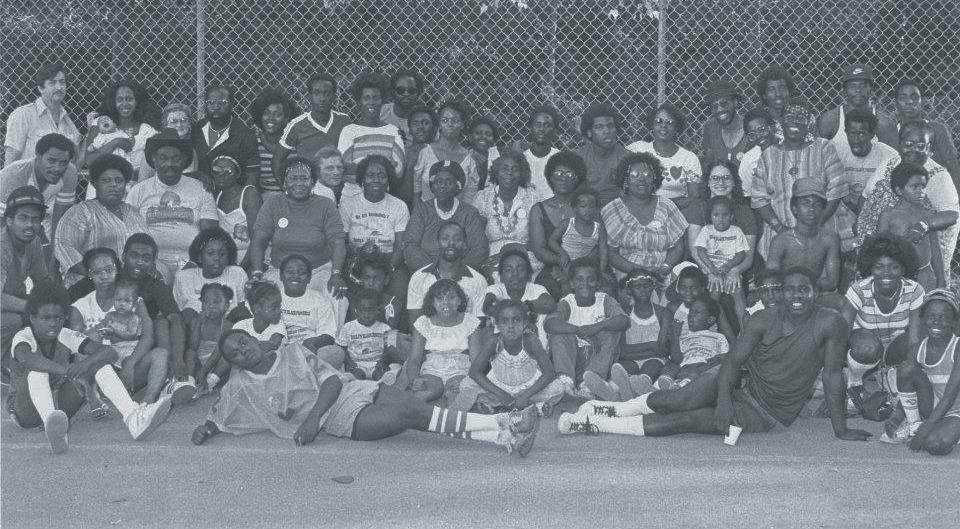

Every August the Craven family upholds an important tradition that began back in 1889. Passersby might take a glimpse of the large African American family and friends celebrating at the Cle Elum Park and not realize there’s more to the scene than a roasted pig, delicious homecooked sides, singing along with Marvin Gaye and games for all generations. But walk a little closer, and visitors will start to hear bits of history preserved, especially from the living of Samuel and Ethel Craven’s 13 children, who are now in their 80s and 90s.

If you incline an ear, you’ll begin to note the substance of a littleknown history. You’ll learn that the Roslyn Black Pioneer Picnic is a tradition that started as Emancipation Proclamation Day celebration. The picnic was noted for its inviting atmosphere not only for family, but for the people of all backgrounds and colors. Newcomers and regular attendees were thrilled to feast on mutton stew and dance into the night on a constructed stage during the earlier years. Though the picnic took a hiatus before World War II, it was revived in 1978 with the efforts of Beulah Craven-Hart, daughter to Samuel and Ethel.

For those unfamiliar with the origins of the small coal mining town, coal seams were discovered in Roslyn back in 1886. Under the ordinance of Logan Bullitt, the town was named Roslyn. It became a well-sought destination for more than 24 ethnicities as word spread that the land was coal rich. Some of the most noted populations included Serbians, Croatians, Poles, Italians, English and Welsh.

The Black miners’ presence started back in 1888-1889 soon after disgruntled miners united with the Knights of Labor and called for a strike. Dissatisfied with the long working hours, the poor pay and the lack of safety conditions, the miners demanded a change and took to picketing. In response the Northern Pacific Railroad brought in more than 300 African American miners from midwestern and eastern states to serve as a replacement over the next six months. It was greatest surge in African American migration to the state.

What follows is a nuanced history, one that is wrought with gains for those looking to the hope of a post-Jim Crow America and setbacks because of some unwilling to honor the progress of an equal nation. “We can memorize what’s written in history (books),” said Harriet Joyce Craven, the matriarch of the family, “but we know that a lot is left out. History is often written by people who want control.”

Northern Pacific was strategic in their ploy, hiring Black businessman Jim Shepperson to do their bidding. Utter his name and some of the Cravens will frown or tell you he was not to be trusted. With the use of brochures that boasted the benefits of

working in the Pacific Northwest, “he was able to lure people with talk of good jobs and good pay,” said Ethel Craven-Sweet, the ninth and last of the Craven daughters and the one named after their mother.

Shepperson told Black miners of the promising employment they’d find in the west. He mentioned a new mine, the No. 3, where laborers were needed. Meanwhile, he failed to mention that a strike had broken out in Roslyn, vital information which would have changed the life course of many had they known. “The labor recruiters weren’t honest,” said Kanashibushan Craven, the eighth of the Craven’s daughters. “They talked about good jobs and wages, but it was a lie. Some smart Black men allowed themselves to be used.”

And despite the fact that Shepperson was responsible for the founding of the Black Free Mason Lodge: Knights of Tabor, two churches and Big Jim’s Colored Club, his initial deception left a sour taste in the mouths of many for years to come. The first 50 or so Black miners to board the trains were from Streator, Ill. Eventually, more than 300 workers would come from states such as Alabama, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia in 1888 and 1889.

The Cravens’ link to the region is their grandmother, Harriet Jackson (Taylor) Williams, who at 17-yearsold, arrived on a train with her young son, Fred. She was escaping an abusive first marriage and eager to make a new life for herself west of the mountains. She succeeded by homesteading over 250 acres. Today she is lauded for her bravery and fortitude. Her image graces the CWU project insert, “Through Open Eyes:

Roslyn’s Black History” and appears on the tops of cakes at family get-togethers.

In 1902, the Cravens’ grandfather, David Williams moved to Roslyn from North Carolina and soon after he married Harriet. In 1906, their mother, Ethel Florence Williams, was born. The first Black miners weren’t made aware there was a strike breaking out over their intended destination until Pinkerton guards joined them on board their trains in Montana. These guards were clutching rifles and handing out some to the passengers, alerting them to the trouble brewing ahead.

“We’re not strikebreakers,” Ethel Craven-Sweet, one of Samuel and Ethel Craven’s daughters, clarified, stressing that this derogatory term was placed upon them and has no part of their identity. “We’re Roslyn’s Black Pioneers,” she said.

Headlines from various publications in the Pacific Northwest tell of the turmoil that awaited the first African American residents. The Daily Oregonian Aug. 20, 1888’s headline reads: “Probably Going to Roslyn: A Special Train Loaded with Negro Miners, Detectives, Winchesters.” The article goes on to tell how the detectives built a barricade of logs and wire to protect the Black miners upon arrival, knowing violence could ensue. Governor Semple sent telegrams to Washington State Attorney General Metcalfe, deeming the influx of Black workers an “outrage” and calling for the arrest of the armed guards (Historylink.org). But upon journeying to Roslyn himself, Semple was able to see that the climate wasn’t as tumultuous as he’d thought. Were the out-of-work miners originally more rattled about their replacement’s skin color, their threatened job

security or both? It’s a question that presents itself even 120 years later. A close examination of written history tells us that the answer is complex at best. After all, a reported 200 white families left Roslyn in early 1889 after their hoped-for terms in the mines weren’t met. Many others returned to the mines and worked with their Black counterparts, reportedly looking beyond race to get a difficult job done. Historical sources remind us, it was difficult to discern one’s color underground.

Working in such close corridors broke racial barriers and created unity unlike many other professions in the country.

A CONTENTIOUS RECEPTION

While it didn’t take long for Black and white miners to work together, what we know of the initial upheaval

Continued on Page 6

tells us that even progressive states like Washington left much to be desired on the road to freedom and equality. Though there are some telling headlines from the time, much of the wrong done is remembered not in writing, but in the memories of Roslyn’s residents.

A Seattle Press journalist wrote, “they came across as slaves, and as slaves they will remain in Roslyn” and then “at the muzzle of Winchester rifles, our free white laborers are displaced by slaves.” And also: “think of the injustice being done to free white miners at Roslyn.”

A headline from Dec. 30, 1888 from The Seattle Press claims that “mob reign rules in Roslyn tonight.” And then a month later, on Jan. 28, 1889, the Tacoma Daily News reported: “Affairs at Roslyn: A Black Miner Shot at a Dance.” The Black miner was reportedly singing at a club. After refusing to stop at the insistence of a drunken white miner, the man was shot and killed.”

The response from the community is not widely recorded, if at all, but reports of subsequent Black miners still being brought to the region follow this early crime. In an article from The Tacoma Daily Ledger on Feb. 15, 1889, it says that “about 300 Blacks arrive at 7 p.m. in eight coaches and three baggage cars.”

At one time tempers over the incoming Black workers struck such a fever pitch that angry Knights of Labor miners dragged Mine Superintendent Alexander Ronald out to the train tracks and tied him down. A railroad brakeman leapt from the train and untied him at the last minute, saving his life. (Roslyn: Images through Time).

While widely reported that the Pinkerton guards did their due diligence in guarding the Black miners, the newcomers lived in fear and were made to live in crude shanties or tents in Jonesville, beyond the town of Roslyn where they’d thought they’d make their homes.

“My grandmother carried a gun in her purse for protection,” Harriet Joyce said, echoing historical accounts that speak to the need for Black people to defend themselves against violence.

“Coal Towns of the Cascades” tell us the white miners who remained were more accepting of the company’s conditions and the fact that they’d work alongside Black miners once the strike ended. While there aren’t written accounts of further bloodshed, we’re told that, “discrimination took such forms as excluding Blacks from the city cemetery.”

Despite the absence of written records on burial rights for African Americans in those initial days, local historian/ Kittitas County Coroner Nick Henderson said that it was common knowledge that there are unmarked graves in Ronald. In fact, he met with Dr. Raymond Hall, a Central Washington University professor with an emphasis in Africana/ Black Studies, who wanted to use ground penetrating radar to identify the graves and place a memorial near the No. 3 mine in Ronald. Hall completed substantial research for the Africana and Black Studies program at CWU and was African American himself. He passed away in the spring of 2019, which left some of his Roslyn research unfinished. (https://www.cwu.edu/anthropology/raymond-hall).

Though there’s insufficient funding at this time, Henderson hopes that more people will become interested in honoring the first Black miners who died with a Memorial. “The area had been leveled by the NWI Company many years ago so we could not use GPR as they did many years ago,” said Henderson. When asked what she knew of unmarked graves,

Harriet Joyce had further insight on the cause of the deaths of the first Black miners to the state.

“There was a creek in Ronald where Blacks were murdered (when they first arrived here),” she said, confirming the century’s-old rumor that there was in fact further violence over the new miners’ arrival. The place they were buried was called N(explitive) Hill. According to Henderson, that location is even listed on residents’ birth certificates, but there is strangely no mention of it in any recorded sources.

Within several years of their arrival there was an established burial ground for Black miners. Anyone who visits the Roslyn Cemetery is undoubtedly fascinated by it: expanding over the hills, the graveyard is segregated, representing the 24 nationalities of people who came to Roslyn. Mt. Olivet, the Black Cemetery, eventually came into being by three Black women: Lilla Nichols, Eva Strong and Sally Claxon (who was married to Jim Shepperson at one time), Harriet Joyce said.

Honoring their ancestors has, in part, encouraged brothers Will, Wes and Nathaniel Craven to work as gravediggers at the Roslyn Cemetery over the years. It’s a work that their father, Samuel —a man noted for his strength — began, and they took on, though Wes is the only one who continues it today. The Cravens’ devotion at Mt. Olivet pays beautiful tribute to the Black pioneers who have passed, including some of the earliest Black miners who weren’t given markers. Though the Craven family is faithful in their maintaining the grounds of remembered loved ones, visitors also can’t help but reflect on the past and the Black pioneers who gave their all to make Roslyn such a thriving coal town.

Back in 1900, 22% of Roslyn was comprised of African American residents. The majority of Black

families arrived between 1888 and 1889 after the call for labor in the mines was sounded by Jim Shepperson, a Black businessman who failed to tell hopeful miners that a strike was ensuing in Roslyn until their trains were already in motion. Though the initial months in the Upper County were contentious between Black and white miners and not without violence, over time the feuds abated. Miners of different races and ethnicities worked together to complete grueling work underground. Many European miners, who weren’t pleased with their unmet working conditions or what they perceived as their “replacement” workers, left town in early 1889.

Over time some Black families left mining for other job opportunities across the state, many of them less harrowing than coal mining. Today there is only one remaining family from the original Black miners, the Cravens. But though they are one family, they have a history wrought with triumphs, sorrows and perseverance that speaks to only those with a pioneering spirit. Their history is upheld by the descendants who speak of the strength of their ancestors and return year by year to attend events like the annual Roslyn Black Pioneer Picnic and New Year’s Celebrations.

At these uplifting gatherings the family talks with pride of their resilient heritage. They are committed in passing this knowledge on to the younger generations. Who could forget that their grandmother Harriet had the tenacity and courage to travel alone with a young child and take to homesteading on her own? And who wouldn’t look to Ethel Florence Craven for her calm and perseverance in raising so many children and still caring for others? And who could forget a man with as much strength, capability, and kindness as Samuel Craven?

Listen to the Cravens for a little while and it won’t take you long to learn more of Roslyn’s storied history. While the town of Roslyn was comprised of more than 24 different nationalities in the early 1900s, there wasn’t a lot of intermingling amongst the races outside of working hours in the early days. The fraternal organizations throughout town had a selfsegregating component to them. Among the Black fraternal organizations in Roslyn were the first Prince Hall Masonic Lodge in Washington territory and a lodge of the Knights of Pythias. Black women joined organizations like Eastern Star and Daughters of the Tabernacle. Black families attended Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches. (www.blackpast. org) While the fraternal organizations and churches were established to assist with members’ care, there were times members of differing organizations crossed paths to help one another. One such occasion came “when the entire community needed a school house, and the Black citizens of Roslyn offered up their church” (www. blackpast.org).

Despite such kindness and the friendships that formed because of it, some Roslyn residents held on to their prejudices. “Even when men were no longer fighting over the mines, prejudice fought for them,” said Kanashibushan Craven of racial climate that persists in the nation at large. “It’s so subtle that it cuts underneath.”

Even years beyond the initial strike, Kanashibushan said “it took a long time for race relations to improve in Roslyn. We were not welcome here.”

Though true that after the strike ended, many Blacks acquired “a social status unlike any they’d ever

Continued from previous page

had before,” it’s suggested that the utmost reason was because of the railroad’s need for more workers (Coal Town of the Cascades). While some friendships formed between the races, the Cravens tell of personal blights they dealt with during their own growing up years, which came long after the first Black miners set foot east of the Cascade Mountains.

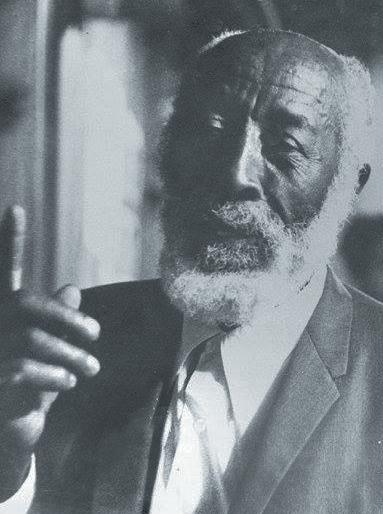

The Cravens’ father, Samuel, came to mine in Roslyn in 1922 from Texas. He’s still highly regarded for the impact he made, breaking barriers to assist his fellow miners and demonstrating a selfless spirit to those around him.

“I got along with everyone (in Roslyn) because of my dad,” said son Will Craven. “He was athletic and he saved a lot of people in accidents. He really understood mining.”

His sister Kanashibushan discussed her father’s attributes at length.

“(Daddy) was tall, handsome, and gentle… I knew he was a helpful man because he’d always help anybody,” she said in an interview on her family lineage (2007). “He had a good sense of humor and a beautiful smile.

“A man came to the house (after my dad died) and he told me my dad he saved many people in the mines. And he was crying, this man was actually crying. And he must have been in his late 60s or 70s. He said what happened was the mine started to cave in, so the head

person said, ‘everyone run.’ And then they ran and got out and then they looked around to see where this gentleman was. And my dad looked around and said he was back there. They said ‘somebody needs to go get him, and nobody would go back. But my dad went back.

And they said he lifted a 1,000-pound rock and carried the man out like a baby…That’s the kind of man my daddy was,” Kanashibushan said.

Will said that their mother was a woman who kept boundaries needed to protect her family. His sister Ethel echoed this sentiment by saying their mother was her “daughters’ protectors” and a staunch disciplinarian, who “watched over her brood, which is a good thing.” Mrs. Craven raised nine daughters and four sons, in that order (one daughter, Georgia Mae, passed away at only 18 months due to health complications). When she wasn’t with her own family, Mrs. Craven assisted others as a midwife, with cleaning homes and watching other children. While her children received their education alongside white students, Mrs. Craven established rules that would keep her children safe.

Her children were allowed to play with white students outdoors, but she didn’t invite them past fence in the 1940s, as a safeguard against judgments on how she ran her household. The Craven children didn’t frequent many restaurants or other establishments as they grew up, given the size of their family, but some of them found fun in sports (baseball was an American phenomenon) or in walking the hill to the Roslyn

Cemetery behind their house, especially on holidays. The Cravens worked hard for everything they had, including a sought-after house on Second Street that became their family home in 1943. Before moving there the Cravens lived with in their grandmother’s 12 room boarding house without an indoor bathroom and a No. 3 metal tub for everyone to bathe in. It was through Samuel and his children’s picking of hops for long hours outside of Yakima that gave them the funds to purchase this new home which came with more space, four bedrooms and a bathroom. The Craven home on Second Street remained with the family for 60 years until a fire devastated the structure in 2009. Thankfully, no one was injured. While sad to see their family home of so many years go, the Cravens’ memories of growing up in Roslyn can’t be compromised. Roslyn remains “home” to those born east of the mountains in the small, promising coal town.

Editor’s note: These are the first two parts of the Craven Family history as told by author Alisa Weis whose love of the creative arts led her to pursue a BA in Literature/ Writing from Whitworth University (2003) and a Masters in Secondary Education (English) from the University of Phoenix (2007).

Parts three an four will apprear in the November issue of 1883 Kittitas County magazine.

In one snapshot Jessee Donaldson is frozen in time: It’s 1902.

He’s sitting up straight in a chair, wearing a striped prison issued shirt and a hardy expression that hints at the struggles he’d overcome. He faced more than your average man and lived to prevail despite so many atrocities placed upon him.

Jessee began his life enslaved by his presumed white father and white stepmother and their children. Joining him in this same household was his Black birth mother and Black half siblings who were also enslaved.

Jessee joined the Union Army exactly one year after the Civil War began to escape slavery. He sustained lifelong injuries that hindered but did not hold him back.

In years to come he and his wife Anna successfully relocated their family 2,500 miles west for a better life in the mining town Roslyn, Wash.

His story wouldn’t be stopped by three months of federal incarceration for a questionable offense. Jessee’s legacy carries on today through the hundreds of Donaldson descendants in Washington state, California, Texas, Ohio and beyond.

In analyzing Jessee’s photo taken 120 years ago, you’ll note his strong jawline and mustache befitting a man at the turn of the 2oth Century. His eyes engage the camera with blurred version, one eye wounded from war, the other looking directly to the camera. Perhaps he realized that this three-month stint served at McNeil Island, charged, and convicted for “selling liquor to an Indian,” would only be a minor setback. His journey was paused but he wouldn’t be stopped for long.

“He was arrested for selling to family!” great great granddaughter Lenora Bentley declared, alluding to the fact that the Donaldsons are a multiracial family comprised of a skin shade spectrum since at least the 1800s.

Jessee’s great (times five) grandson, Ryan Anthony Donaldson, who works as an archivist, gazed upon Jessee’s image at the National Archives at Seattle for the first time along with his father, Ray Donaldson, cousin Butch Smith and Butch’s son Greg Smith, and can’t stop reflecting on the experience. To say he was moved is an understatement.

Ryan was notified of the image’s existence from Seattle historian, genealogist and author Cynthia A. Wilson, who is designating a chapter of her upcoming book on United States Colored Troops to Jessee Donaldson’s legacy. Jessee joins 31 men that Wilson researched for her book. The four Donaldson men left the archives in awe to finally behold a verified photo of Jessee and that he will be featured in Wilson’s book.

For years they’d thought that Jessee was another man, identified in an early family photograph. They were astonished to realize

Jessee appeared different than the man whose face they’d come to see as their patriarch.

As elusive as his likeness might be until now, details of Jessee’s journey are recorded so that his descendants might know and remember the steep price he paid for his freedom and their own.

The Donaldsons also draw awareness to the fact that they share many white relatives tracing back to the Revolutionary War, but they look to Jessee as their biracial forefather with good reason. That said, more than a few of Jessee’s kin express interest in knowing and meeting more of their white side “as long as we take care of the Black side first.”

It was the mid 1980s one of Jessee’s descendants, Lillian “Babe” (Donaldson) Warren, ventured to the coal mining town of Roslyn, Wash. with her husband, Robert Williams, for the first time.

While there, she found herself walking the strangely familiar terrain her Donaldson descendants had trod 100 years before.

She started letting her imagination take flight. What must their lives have been like? What were their struggles? Their triumphs? Their unique experiences? What could she uncover about their stories as one large family within the Pacific Northwest Black Pioneers community?

Babe went to spoken-of haunts: everywhere from the Ronald No. 3 mine where her ancestors worked to the Mt. Olivet Cemetery where Jessee, his son Thad, daughter Rusia and

Continued from previous page

reapplying for lengthy applications and affidavits, while being examined by doctors dubious of his true condition.

It was later discovered that Jessee was jailed in Tennessee from 1871-1873 for allegedly “stealing hogs.” Though Babe didn’t include this account in The Red Book—perhaps to appease relatives who didn’t want the past publicized, to protect Jessee’s legacy or because the documentation was not available to her — the Donaldsons recently learned more details of his difficult experiences in the Jim Crow South.

Ryan recognizes how uncanny it is that sections of Jessee’s story have seemingly fallen in his lap. He may have set out to visit his ancestor’s past dwelling places, but he didn’t expect the Donaldson plantation site to be only half an hour driving distance from his wife’s childhood home.

Likewise, in searching for Jessee’s past records, Ryan learned of the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America project and found Jessee’s name mentioned in a multi-year batch of Pulaski Citizen newspapers. More research showed the county prison where Jessee was held was burned to the ground, so Ryan was amazed to find the old prison ledger preserved during a visit to the Giles County Courthouse.

“We were able to hold 150-year-old documents, and it was almost poetic,” Ryan said. “You can see the smoke seemingly smoldering on it and the water stains. The fact that it survived and that it’s there for us to see is remarkable.”

Invited to inspect the local jail’s mobile holding pen, a historic relic similar to the one Jessee was made to

rest while performing the manual labor of his sentence, Ryan recoiled. Realizing that farm animals are treated better, he was unprepared to further explore the inhumanity of his ancestor’s living conditions.

“His story is one of justice deferred,” Ryan said, alluding to the fact it took three entire years to schedule Jessee’s trial, with his sentence ultimately a fraction of the time he was imprisoned. “Going to the courthouse in Tennessee, I was struck by the coarse indignity that denied his freedom yet again.”

In The Odyssey, there’s record of Jessee’s first marriage to a woman named Lizzie, who passed away soon after they married. Jessee remarried to Anna Smalley in 1875 in Georgia. Family tradition describes Anna as having African and Native American ancestry. The Donaldsons have one photograph they believe to be her, handed down to them. They are interested in elevating what is known about their matriarch.

Digitized period newspapers such as the Seattle Republican reveal that Anna was a leader in the local Mt. Zion Baptist church, traveled to Cincinnati as a delegate for a national Baptist convention and volunteered with the Home Foreign Mission Circle. But beyond that, Anna remains an elusive yet equally important presence, as Jessee’s life partner and the mother to their 10 children, seven of whom survived to adulthood. Their names are as follows: Hattie (born 1876), General (“J.J.” born 1878), Thad (born 1881), Mary (born 1885), Elizabeth (“Lizzie” born 1888), George (“Sharkey” born 1890) and William (“Peck” born 1893). Today, there are six branches residing throughout Washington state, California, Texas, Ohio and beyond.

“I feel called and compelled to tell Jessee’s story,”

said Ryan. “It interacts so much with U.S. history and is laced through so many eras. I’m living and embracing this laid out path, so many [of my family’s anecdotes] have found me.”

Over his lifetime, Jessee toiled in numerous trades to make a living. He was a Union soldier. A farmer. A coal miner. It was the late 1890s, in fact, when coal called. There was such a high demand to extract coal from the earth that Jessee, like many hardworking men, heeded its call. As labor unions formed and white miners striked for better wages and other benefits, recruitment intensified for Chinese American workers and later African American workers. Jessee and Anna’s embrace of the opportunity to move their family west proved to be a seismic change for their future. Jessee’s son, General, would also take part in the same coal mining venture as his father and was the first family member to see the Pacific Northwest with his own eyes.

Editor’s note: This is the first and second parts of the Jessee Donaldson Family’s history as told by Alisa Weis and Ryan Anthony Donaldson. Much of the information came from the research of Lillian “Babe” (Donaldson) Warren and her husband Robert E. Williams through “The Donaldson Odyssey: Footsteps to Freedom” as well as the continued efforts of Donaldson family to bring their family history to light.

Parts three through five will appear in the November edition of 1883 Kittitas County.

town, Roslyn was rebuilt using brick and sturdier materials. A short time later mine workers, angry that the coal company had laid off miners who had petitioned for an eight-hour work day and higher wages, went on strike.

In response, management began recruiting strikebreakers, including some 50 African American laborers from the East and Midwest. Eventually, the company brought in more than 300 African American workers and their families, including many from Virginia, North Carolina and Kentucky. While initially tensions were high between the striking workers and the newcomers, relations cooled after the strike ended a few months later. By 1890, Roslyn’s African American citizens represented more than 22 percent of the overall population of the town, making it one of the highest in the state.

In 1892, Roslyn experienced its worst-ever mining accident when an explosion and fire in Mine No. 1 killed 45 miners. Workers had been in the process of connecting an airway from the fifth level to the sixth level (the mine went down seven levels, to a depth of 2,700 feet), when blasting powder used to break the rock ignited a pocket of gas. Miners not killed immediately by the blast quickly suffocated.

A second equally-devastating mining disaster struck the community on Oct. 3, 1909 when another underground explosion killed 10 workers. The following day Portland’s Morning Oregonian reported that the loss of life could have been far worse had the blast occurred not only a Sunday but during a regular work day when as many as 500 workers would have been in the mine. The paper said the cause of the explosion was still under investigation.

The following year was the peak in terms of the community’s size, when it boasted a population of 3,126. With a decline in the use of coal because of the increasing popularity of other fuels such as diesel oil, Roslyn began a gradual decline. The last coal mine in operation closed in 1963, marking the end of an era.

But the town’s deep and abiding connection to its mining roots served as the impetus for the creation of the Miner Memorial in the mid-1990s. In 1995, the Roslyn/Ronald Heritage Club proposed erecting a permanent monument to the region’s mining past. By June of the following year work had begun to erect a lifesize bronze statue of a miner and a black-tile memorial wall that would display the names of all local miners and their families.

Funding for the $20,000 statue, which was sculpted by Pacific Northwest artist (and Central Washington University graduate) Michael Maiden and entitled “The End of the Day,” came from donations and the sale of 6 x 9 commemorative tiles.

Statue committee chair Tony Alquist, who grew up in Roslyn and died in 2006 at the age of 95, told the Ellensburg Daily Record on July 5, 1996, “We want this memorial to honor the local miners—not as tired, beaten men—but as warmhearted, family men who appreciated having a good day in the mines.” He added that was the reason the miner was smiling.

On Sunday, Sept. 1, 1996, in front of what the Daily Record described as a “crushing crowd of people,” the Roslyn Coal Miners’ Memorial was officially unveiled. Standing in front of the historic former Company Store (formally known as the Northwest Improvement Company building) on Pennsylvania Avenue, the monument is a celebration of the town’s rich mining history and culture.

“They came to honor Roslyn’s heritage, a colorful microcosm of this country’s origin,” Pat Woodell wrote in the Daily Record on the dedication day. “They came to honor the miners who arrived ‘from the old country’ to work the coal mines and make a new life for themselves.”

Among the speakers that day were sculptor Maiden, along with representatives of the Washington State Heritage Society, the Roslyn/Ronald Heritage Club and the city of Roslyn.

Of special note was the inclusion of a time capsule in the statue’s pedestal, not to be opened for 60 years, which was prepared by Roslyn High students. It was no doubt fitting that the next generation helped to honor its predecessors.

— Richard Moreno is the author of 14 books, including Frontier Fake News: Nevada’s Sagebrush Hoaxsters and Humorists and the forthcoming Washington Historic Places on the National Register. He is the former director of executive communications at Central Washington University and was honored with the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame Silver Pen Award in 2007.

“Letters” by Oliver Sacks, edited by Kate Edgar Dr. Oliver Sacks, acclaimed author of books such as “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” and “Awakenings,” was a committed letter writer throughout his life. This new work collects the insightful notes he wrote to his parents, friends, colleagues, his beloved Auntie Len and many others from the time he arrived in the U.S. from England as a young man, through different stages of his life (Sacks died in 2015 at the age of 82). According to

the New York Times Book Review, the book reveals “his passion for life and work, friendship and art, medicine and society, and the richness of his relationships with friends, family, and fellow intellectuals over the decades.”

“Orbital: A Novel” by Samantha Harvey Winner of the 2024 Booker Prize, Samantha Harvey’s Orbital follows one day in the lives of six men and women traveling through space. The crew, which includes members from America, Britain, Russia, Italy,

Elizabeth Lim

This new book by Elizabeth Lim is an exciting sequel to “Six Crimson Cranes,” her successful fantasy YA novel released in 2021. In this work, Lim tells the story of Princess Shiori, who makes a deathbed promise to return a dragon’s pearl to its rightful owner. To do so, she must journey to the kingdom of dragons, survive political intrigue among humans and dragons, and fight thieves attempting to liberate the pearl from her. The trick is that the pearl emanates a malevolent power of its own, which threatens to betray the princess at any moment.

author and photographer Shelley

With simple text and photos depicting matter includes easy-to-use activities to

• The Ellensburg Public Library offers Neuro-Friendly Storytime programs? Neuro-diverse youth and their families are welcome to participate in a fun, interactive and well-supported storytime that includes a variety of sensory engagement tools and activities. Contact the library at 509-962-7250 to find out when the next one is scheduled.

• The Ellensburg Public Library is open Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

— The Reference Desk: What’s New at the Ellensburg Library is written by Richard Moreno

Ken MacRae, DVM worked alongside Dr. Newman at Ellensburg Animal Hospital and tells the story of the early days, just joining the practice, and a conversation with Mrs. Newman, wife of Dr. Leonard Newman.

Ken’s Musings Stories and Memories

By Kenneth R. MacRae

One story I cannot leave out happened one day shortly after I had joined Dr. Leonard Newman in practice.

In those early days we still used liquid ether as our anesthetic for cats. The procedure required one person to hold the cat’s four legs and the other person to restrain the animal’s head by holding it forcefully into the open end of a soup can that had cotton soaked in either in the bottom. The animals struggled mightily and since I had undergone much this same procedure as a child during tonsillectomy surgery, I was aware how

unpleasant the experience was.

This day our patient was a young tomcat to operate on for the neutering that was the commonest surgery we performed.

I was just making conversation when I remarked to Mrs. Newman, “This is probably the cruelest thing we do to animals.”

“Why do you say that?” she asked.

I replied, “I know because I’ve had it done to me”

Mrs. Newman, wide-eyed replied “You have?”

“Yes,” I said, “When I was about 8-years-old.”

“You mean castration?” she asked.

“No! No!” I said, “I mean ether anesthesia!”

As my Aunt Mary Andlar, who operated Roslyn’s old Freezer Shop, told me, families in the old country had been making their own wine for centuries. When they came here it was no different. They always had their own homemade wine or slivovitz (brandy) on hand, and when company came to visit, the first thing they did was offer you a glassful. I found this tradition to still be true when visiting Croatia a few years ago and was given a glass of home brew at every single home I visited. It was a lovely, inviting gesture that had been passed down for centuries.

With that cultural history ingrained in most of the Upper County population, I had two questions to answer for this report: 1. How in the world did the idea of Prohibition ever come about? and 2. How did our Upper County folks deal with it?

I’ll start with a short history of how Prohibition came about. The first serious anti-alcohol crusade in the United States actually started around the 1830s-1840s with the Temperance Movement. The Temperance Movement was formed during a period of intense religious revival primarily by women who protested against the use of alcohol.

They saw alcohol as the root cause of many social ills including domestic violence, family abandonment, workplace accidents, political corruption and prostitution. This Movement eventually led to the formation of a powerful organization called the Anti- Saloon League, founded in 1893. Their efforts in lobbying for prohibition was so effective that by 1913, nearly half the United States had gone “dry” though local option laws that allowed voters to ban alcohol sales on a district-by-district basis.

By1917, Congress passed the 18th Amendment which illegalized the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol. This National Prohibition act was sponsored by Republican Minnesota congressman Andrew Volstead, which is why some refer to Prohibition as the Volstead Act. The 18th Amendment was ratified on Jan. 16, 1919, and the country officially went “dry” on Jan. 18, 1920. Washington state, though, was ahead of the game. Efforts here to outlaw the sale of alcohol actually started in 1854. Then in 1914 the Prohibition amendment to the U.S. constitution passed in Washington state. Ellensburg was one of the first cities in the state to go dry in 1914. By 1916, state-wide Prohibition was enacted –three years before the United States ratified the 18th Amendment. That bit of history answered my first question of how Prohibition came about. Now I’d like to get into the more interesting details of my second question of “How the Upper County folks responded to Prohibition.”

Prior to 1916, the Upper County enjoyed a “wet” climate. Ellensburg had gone dry two years earlier, so us “Hooligans” in the

Upper County must have really lifted a few eyebrows down there. It’s been reported that back then every other door in downtown Roslyn was that of a tavern, plus the immigrants were brewing their own drink at home. Roslyn alone was reported to have 27 taverns. This was due to the fact that there were 27 different ethnic groups here and each group had their own lodge, their own cemetery and their own tavern. But the “dry” laws were going to change that — right?

Not so, according to one of our old timers, Mary Brozovich. Mary was born in Roslyn in 1917 and started working for her dad, Marco Korich, at his tavern, Marko’s Saloon, in 1930 — three years before she graduated high school and three years before the end of Prohibition. She passed away in Roslyn in 2012 at the age of 95. When interviewed by Fred Krueger in 1999 she recalled her days at the saloon as business as usual and the community continuing to enjoy a very “wet” climate. (“Mary Brozovich Interview” (1999). Roslyn, Cle Elum, and Ronald Oral History Interviews. 15.)

With the “dry” laws coming into play on the Firstt of January 1916, the Cle Elum Echo newspaper reported on Dec. 31, 1915, that most of the saloon men were “in favor of having the prohibition law enforced to the letter so that the people who voted it in could see the real merits of the issue.” The report went on to describe the current saloon status in the Upper County and described how they planned to deal with the new law.

That report said there were 40 saloons here: 23 in Roslyn, 12 in Cle Elum, three in South Cle Elum andtwoin Ronald. It didn’t mention any saloons in Easton, but since it was a railroad town I can only assume they had at least one. Of the 12 saloons operating in Cle Elum, six planned to change their operations to ice cream parlors, card rooms, soda fountains and candy stores.

Prohibition affected the operations of all the taverns in the Upper County, but there were other changes made in response to the new law. One change made was the appointment of a new deputy sheriff for the Upper County – that of W. C. Minton, the former chief of police of Ellensburg. Another couple of changes made came about from loop holes in the Prohibition Law. When the law was first passed, doctors could prescribe booze to help patients with their maladies, but this loophole was soon cleared up and the upper county doctors and drug stores got together and agreed among themselves that no one should obtain a prescription for intoxicating liquor from them unless it was a case of absolute necessity.

Another loophole in the original law allowed the selling of liquor permits which allowed the permit holder to buy two quarts of hard liquor. Permits were sold by the County Auditor’s Office for $3 each (which was a considerable sum in those days). The one month of

‘Ladies of the evening’ are a colorful part of Upper County history

Cle Elum was a rough town for years, full of loggers and miners. From far away the Italians, Croats, Poles and Slovaks heard of Cle Elum and the coal mines and they came by the hundreds. The expensive trip prevented many of the men from bringing their wives, sweethearts and families to Cle Elum. The men boarded until they could save enough money to send for their loved ones. Soon the prostitutes came in by rail and later by bus or car to take advantage and cash in on the situation. They would be working on Railroad Street.

As one lifelong old timer explained it, “There were five houses, all on Railroad Street. The Burcham Hotel was one the main houses.”

Another old timer said, “Cle Elum was a Wide Awake town.”

None of the women were from the Upper County. They spent money freely around town at the jewelry store and other businesses. They visited the doctors for regular checkups. After a while they would leave town and a new group would come in.

The old timer said, “Church goers ran them out.”

Following is a newspaper account of a move made by Mayor Morton to close these houses:

That at all times between Jan. 4, 1949 when Morton took office, and Jan. 1, 1952 houses of prostitution “operated openly and notoriously in the city … (three in number) were required to post bail in the amount of $75 each every six months as a condition precedent to their continuation in business,” that the mayor caused them to cease operating Jan. 1.

There were many stories. One of the girls stayed many years after the houses were shut down in the ’50s. She was a kind, thoughtful and pleasant person who was always going to save her money and go back to the state she came from. She passed away before she could get home.

Some of the old gentlemen who were spending their last days in the Cle Elum nursing home would often mistake the staff as “ladies of the evening.”

A newspaper report from May, 1914: DISSOLUTE WOMAN HURLS HERSELF IN YAKIMA AND SOON DISAPPEARS

Annetta Brown, as she was known in Cle Elum, was about 27-years-old and a dissolute woman with something of a bad record in Cle Elum. She was once mixed up in a knife scrape. When the trouble that followed was passed on, the woman was in Ellensburg. There the authorities had trouble with her and she drifted back to Cle Elum. She congregated with some others at Frank Dere’s place, was arrested and brought into police court. She was fined Monday and given 24 hours to leave town.

Tuesday morning she bought a ticket to Roslyn and checked her trunk there. About noon

Continued from previous page

“K-9s certified in HRD have by far the most activity,” Ybarra explained. “After that, it would be the evidence dogs … then trailing is next busiest for like when kids wander off a trail or people with dementia get lost.”

When asked what his dogs Ember and Roci think about all this work, Ybarra stated that it’s more of a game for them.

“They’re not out there being heroes saving lives,” he said about his beloved dogs. “They know when they do a good job when they get their favorite toy or reward.”

Nale referenced the great success the volunteer SAR K-9 team has brought to rescue efforts, with a focus on the evidence and HRD K-9s.

“The group trains really hard and they put in hundreds of hours of training a year … they train weekly” he explained.

Ybarra echoed Nale’s sentiment about the dedication needed to provide experienced and qualified SAR K-9s, as certification and training costs thousands of dollars over a dog’s lifetime and it takes anywhere from four to 25 hours a week of training time to get the K-9s prepared for their certifications. There are some additional difficulties related to the nature of the organization on top of the K-9 teams’ training time and cost.

Every spring there is an academy training course for new recruits to get all volunteers the required statemandated training.

“The academy is only once a year, it’s a small window for new volunteers … the turnover is high because it’s a hit and miss agency,” Ybarra said.

These challenges don’t deter him from maintaining a strong presence in SAR. Now that he is an experienced member, he enjoys the chance to teach new generations of volunteers. He says he loves being able to help people and that he loves having a real purpose to go out into the woods.

Kittitas County SAR efforts are made possible by dedicated volunteers and all materials and equipment are paid for by donations. The organization often partners with local breweries such as Iron Horse, Whipsaw and Dru Bru where proceeds from pint night sales are donated to the organization. Members walk in local parades and have booths at farmers’ markets.

To learn more, get involved or provide donations, visit the Kittitas County SAR website, Facebook and Instagram or stop by the booth at the Sept. 27 at the Ellensburg Farmers Market.

— Madelynn Shortt is a freelance journalist published in The Yakima Valley Business Times, The Ellensburg Daily Record and KV Living Magazine.

Left: Kittitas County Search and Rescue members wheel a patient out of the woods during a mock missing.

Top right: SAR members assist in loading a patient into a LifeFlight helicopter.

Below far right: SAR member and K-9 handler Wendy Neet with her dog, Oakley. The 2-year-old Cane Corso specializes in trailing. Her favorite rewards are chicken and his squeaky toy. Contributed photos

*In case of emergency, always call 911; do not call SAR directly as they are only ever dispatched through approval of the Kittitas County Sherrif’s Office.

SEPTEMBER 3

Bike Night, The Porch, 6pm Bingo, Whipsaw Brewing, 6pm RDA Roslyn Music Jam, Roslyn Creative Center, 6:30pm Trivia, Iron Horse Brewery, 6:30pm

SEPTEMBER 4

The Wall That Heals Opening Ceremony, Rotary Park, 9am Open Mic Poetry, Club 301, 6pm

SEPTEMBER 5

The Wall That Heals, Rotary Park, open 24 hours Yard Sale at KVUUC, 400 N Anderson Ellensburg, Noon First Friday Art Walk, Ellensburg, 6pm

Big Sky: Modern Mountain Art Show, Nuwave Gallery, 5pm Blusers, Gard Vintners, 6pm Kyle Bain, Valo Tasting Room, 6pm

Trick Pony, The Brick Saloon, 9pm Kevin, Nodding Donkey Bar, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 6

The Wall That Heals, Rotary Park, open 24 hours Ellensburg Farmers Market, Downtown Ellensburg, 9am Roslyn’s Women’s Mountain Bike Ride, Roslyn Yard, 9am Mary Duke, Art in the Park, Unity Park Ellensburg, 10am Snow White, Roslyn Yard, 7:30pm The Canyoneros + Tinned Fish, Iron Horse Brewery, 6pm YouFouric, Cle Elum Eagles, 7pm Santo Poco, The Brick Saloon, 9pm

Roadfever, Unity Park, 5pm

SEPTEMBER 7

The Wall That Heals, Rotary Park

Roslyn Farmers Market, Downtown Roslyn, 10am

SEPTEMBER 8

Noontime Ukulele Club ages 15115, 201 N Pearl, 12:10pm Trivia, Whipsaw Brewing, 6pm

SEPTEMBER 9

Kittitas County Master Gardener Plant Clinic, The Armory, 11:30am

Paint Party, Valo Tasting Room, 5:30pm

Poirot Tuesdays, 420 Loft Gallery, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 10

Bingo, Whipsaw Brewing, 6pm

Mr. G, Gard Vintners, 5pm

SEPTEMBER 11

United We Stand. Remembering September 11, 2001

SEPTEMBER 12

Petting Zoo & Crafts, 730 Alford Road Ellensburg, 10am

Barbie, Roslyn Yard, 7:20pm EHS Football vs Selah, Ellensburg High School, 7pm Cirque ma’Ceo - Ellensburg, KV Event Center, 7pm

Jesse James & The Mob, Gard Vintners, 6pm

Kyle James & The Hay Dogs, Iron Horse Brewery, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 13

Community Apple Pressing party, Wheel Line Cider, 10am Blues, Brews & BBQ, 671

Midfield Drive Ellensburg, 4:30pm

Quilters Yard Sale, Ellensburg Presbyterian Church, 8am

Mel Peterson, Whipsaw, 6pm

Dirtbag Carnival 2025, Iron Horse Brewery, 4pm

Star Anna, Kittitas Cafe, 7pm

Under the Covers, Wenas Creek

Saloon, 8:30pm

Mufasa, Roslyn Yard, Roslyn, 7:20pm

Contraband, Cle Elum Eagles, 7pm

Darci Carlson, The Brick Saloon, 9pm

Karaoke, Nodding Donkey Bar, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 15

Ellensburg Swing Dance Project, Hal Holmes Community Center, 7pm

Brochet Night, Iron Horse Brewery, 5:30pm Trivia, Whipsaw, 6pm

Readers Theatre VTC Script in Hand Series, Gard Vintners, 6:30pm

SEPTEMBER 16

Kittitas County Master Gardener Plant Clinic, The Armory, 11:30am

Paint & Sip, Whipsaw Brewery, 6pm

Poirot Tuesdays, 420 Loft Gallery, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 17

UKCSC Field Trip Bus Legends Casino, UKCSC Centennial Center, 10am

Knudson Lumber 85th

Anniversary Bash & Barbecue, Vantage Hwy, 11am

Bingo, Whipsaw Brewing, 6pm

SEPTEMBER 18

Mel & Dre, The Brick House Nursery, 5pm

SEPTEMBER 19

Mikestoberfest 2025, Mikes Tavern Cle Elum, 5pm Loco Motion, Gard Vintners, 6pm

Teanaway Ranching with Phil Hess, Carpenter House Basement Cle Elum, 5:30pm

Poetry Open Mic, Roslyn Public Library, 7pm

The Boys in the Boat, Roslyn Yard, 7:10pm

Vaught Rock, Nodding Donkey Bar, 7pm

SEPTEMBER 20

Ellensburg Farmers Market, Downtown Ellensburg, 9am

Cle Elum Cars & coffee, Dru Bru Cle Elum, 10am

Oktoberfest, Dru Bru Cle Elum, 11am Cle Elum Eagles Crab & Chowder Feed, Cle Elum Eagles, 4pm

Hip-hop of Hades, Old Skool’s, 7pm

Auditions: Cabernet Cabaret Broadway’s Dark Side, Make Music Ellensburg, 9am

Auditions: Twas the Night Before Christmas, 118 E 4th Ellensburg, 3:30pm

Gallop to Greatness Dinner & Auction, Spirit Therapeutic Riding Center, 5:30pm

Abbigale, Kittitas Cafe, 7pm

Fish Food Bank Pint Night, Iron Horse Brewery, 1pm Wicked, Roslyn Yard, Roslyn