As autumn settles into Kittitas County, the crisp air and golden leaves remind us to slow down, explore and truly appreciate the beauty in both our community and one another. Fall is a season of gathering—whether that’s strolling through a local market, visiting a favorite shop, enjoying a hometown event or simply sharing a cup of cider with a neighbor on the porch.

This season, let’s lean into kindness. Support a local business, cheer

on a musician or invite a friend to join you at one of the many fall happenings across our valley. Every small act of support strengthens the threads that connect us, weaving together the vibrant community we all call home.

Cheers to a season of kindness, connection and celebration.

Robyn Smith, Publisher Andrea Paris, Editor/Designer

Editor’s note: This is the conclusion of the Craven Family history as told by author Alisa Weis

While true that tensions eased after the strike of 1888/1889 ended and that Black and white miners worked together, the Craven family still experienced barriers because of their color.

Ethel Craven-Sweet said that her family would go to the Company Store (as did all the miners) for goods, but there was at least one occasion where one of her older sisters wasn’t given the items she requested.

When her sister told the clerk she needed sanitary napkins, she was turned down and told “you don’t need that.” Once their father Samuel heard of this, he reported to the Company Store, and no one denied him. The clerk’s initial refusal led Ethel to say, “the Company Store was not a pleasant place.”

While the Cravens excelled in their studies, not all teachers and students were willing to acknowledge the awards they’d earned. Ethel recounts being the Valedictorian of her class, but says that title was taken from her because of her race.

“Being the Valedictorian is such an honor, and then someone snatches it from you,” said Kanashibushan, reflecting on the disappointment and anger her younger sister must have felt. “My mother went to speak with the principal. He apologized, but said he wouldn’t have a job if he allowed her to be Valedictorian. I don’t agree with his decision, but I understand it…It takes more courage to do what’s right, but that’s asking a lot sometimes.”

Ethel said that while were some good teachers, the music teacher in Roslyn was prejudiced. “She would not let my sister or me sing during school performances and told us to sit down. After eighth grade my parents sent us to school in Easton (since we were treated better there.) Roslyn provided a good education, but there were things that made growing up here an unhappy time.”

Kanashibushan added that if she and her sisters experienced these slights from some of Roslyn’s teachers, she knew it must have been even harder for her brothers.

Ethel credits her parents for insisting their children take her studies seriously. She and her siblings worked diligently toward their varied dreams and aspirations. While their paths often took them in various directions, the Cravens are noted for being difference makers in whatever field they followed.

Ethel completed her shorthand training at Edison Technical College (now part of Seattle Community College) and became the second African American woman to work for Boeing in 1958. She was brought on as a secretary, but said that in the early days that the personnel clerk “tried to hide me.” Her employer moved her to

the Central Medical Library, which was secluded from the main place, but six months later, she became a secretary to doctors and was in a position that involved working with a lot of people and “being seen.”

Harriet Joyce echoed some of her sister’s experiences, saying that while school wasn’t segregated, she was only invited to about two classmates’ birthday parties over the years and “never got to go to school dances.” In 1947, she was one of two African American students to attend Central Washington State College. Four years later she graduated with three Bachelor degrees.

“In 1951 only two schools would interview me for a teaching position,” she said. She had to leave Washington since Portland, Ore. was one of the only districts that would offer her a position. “At first I was only allowed to scrub floors or work at restaurants.”

Ethel Craven-Sweet in her beautiful yellow graduation dress. She was the Valedictorian of Easton High School in 1953. Photo courtesy of the Craven Family

Her sister, Kanashibushan, reiterated that Roslyn was not a place where Black women could readily find work; they had to go to other towns to find positions even for cleaning or waitressing.

Kanashibushan earned her Business degree from Griffin Murphy, but was quickly disappointed when denied opportunities

because of her color. At 43, after spending years raising children, she went back to school at Seattle Central Community College for a degree in Mental Health/ Human Services and was able to connect with people in need through Seattle housing and runaway shelters.

Kanashibushan also found a calling in working as a psychic. She studied metaphysics for 15 years, worked alongside psychic healers in London, and “is not so much a predictor of wild, unknown events...as she is a confirmer of things people already sense” (The Daily Record article). There’s a natural strength and calm to her that draws people to her for guidance.

Wes found success and acclaim in the boxing ring. Before a serious eye injury eventually sidelined him, he was a Golden Glove Heavyweight and Welterweight champion in Seattle. One of his championship pictures is proudly on display at the Roslyn Historical Museum, and he is mentioned in local history books for his accomplishments in the sport.

One of the family’s greatest triumphs came when Will Craven was appointed as the first Black mayor not only to Roslyn, but in Washington state in June of 1975. He ran for the vacant position in 1976 and won by a great majority of votes. Will filled this role for four years and earned a lot of recognition for his civil service. What’s so incredible—and ironic—about this appointment is that Will is a descendant of the Black miners whose train was initially chased out of Roslyn by striking miners.

“Some people will like me, some people won’t,” Will said in an interview for The Spokesman Review during his years as mayor. “I didn’t run for this job as a Black man, but as a man. I wanted an equal chance to try.”

Though his responsibilities as mayor ended long ago, Will’s accomplishments as mayor are upheld and remembered. Nov. 3, 2015 was deemed “William Craven Day” in honor of his service 40 years prior and the history that was made through his appointment.

The Craven family have proven gracious educators to all those in the Pacific Northwest who have expressed interest in knowing their history. Before her passing in 1993, reporters would approach Mrs. Craven since she had a photogenic memory until her later years. She was passionate about people knowing of the impact made by Roslyn’s Black Pioneers.

“My sisters and I went to school districts across the state to give presentations,” said Ethel. “The junior high students loved our talks on Roslyn Black Pioneer history. Some of the things we shared with them included coal from the mines, a washtub from the past, and an old train model. We got a lot of letters from kids thanking us for being there over the years.”

Roslyn residents of the 1980s and ’90s are sure to remember the vibrant floats the Cravens created to pay tribute to their ancestors and raise awareness of their Washington presence. Ethel fondly recalls floats from years gone by, especially since she was in charge of creating them. The Cravens participated in upward of 13 parades a year, which carried them anywhere from Yakima to Olympia. Mrs. Ethel Craven joined in to represent in Roslyn/ Cle Elum and was the first African American hailed as Pioneer Queen in 1983.

One year 19 people were on board, including three

babies, and they couldn’t have had more fun. Ethel recalls wearing a shimmering “shake shake” silver dress, delighted to have the chance to wear it, all the while knowing that the Roslyn Black Pioneers were being recognized. “We had so much fun. People liked us because we were noisy,” she said, with a laugh. “We had our last float in 1998, but I’m so thankful for the memories. We had a ball.”

The Cravens have also proven strong activists for Civil Rights, partaking in marches and protests in Seattle and Olympia over the years. Harriet Joyce had the opportunity to march with Dr. King, and she was given an award from Jesse Jackson for her efforts to further the work of justice and equality. Her oldest sister, Leola Woffort, is remembered as a brilliant woman who led her siblings in the fight for justice and championed for welfare rights no matter the person’s color. The sisters were devoted to affecting positive change in as many lives as they could reach.

While able to look back and draw on the strength and perseverance of their ancestors, the Cravens are ever aware of the work that still needs to happen at local and state levels and will continue to speak out on that which matters. One of the first ways to introduce others to this work is to educate on their family history, one that still isn’t rightly recognized in enough historical accounts. Knowledge of Roslyn’s Black pioneers gives more hope and fuel to today’s generation and all that will follow.

“It’s important to know that Black people were part of the pioneer energy,” said Kanashibushan. “We have a pioneer spirit. It took something for my grandmother to come as far as she did with a child. Almost 3,000 miles.”

Chamara Smith was mourning the loss of her grandmother, Joyce, when she was recently greeted by a blueish gray hummingbird that wanted to linger.

This one didn’t come to simply drink and fly off to feeders in other yards. It stayed awhile on her porch.

“It was singing. This one was different,” Chamara said. “I felt my grandmother’s spirit. It was her

personality. What the hummingbird did, like how it danced, sang and did a little wink at the end. Like my grandmother used to do.”

This hummingbird made Chamara wonder if her grandmother just might be sending her a comforting sign that she was with her in the midst of her sorrow. If so, it was in her grandmother’s nurturing nature to do so.

Harriet Joyce (Craven) Hawkins – Joyce to those who knew her well – graced this earth for more than 91 years, and what a full, beautiful, accomplished life she lived.

Not long into a conversation about Joyce, and you hear of her tremendous faith in God.

“Joyce was a prayer warrior,” said her younger sister, Kanashibushan Craven. “Those who knew her, knew not to call her between 7 and 8 in the morning because she was praying.”

This faith, which guided her life’s path, began in her early years. It sustained her through trying and uplifting times and gave her a peace that drew others to her.

As many in Roslyn know, Joyce was a descendant of the first Black miners to arrive on Washington soil. In her later years, she became known as the matriarch of the Craven family, the only remaining Black family from that era to still call Roslyn their home.

For those unfamiliar with the history, back in 1888/89, more than 300 Black miners and their families migrated to Roslyn after being told they would have promising positions in the new No. 3 Mine. They weren’t told until their trains arrived in Montana that they would be used to break a contentious strike with angry European miners who wanted better pay and safer conditions. Despite this contentious reception, Black and white miners eventually worked together,

Continued from Page 5

putting aside difference in color to get a hard job done. Over time, most Black families sought work opportunities across the state, but the Cravens remained.

Joyce was Samuel and Ethel Craven’s fourth daughter. The couple had nine daughters, followed by four sons. Joyce “was known as a beauty,” said her daughter, Merrilee Smith.

She had a few health challenges with her appendix when she was young, which meant she wasn’t expected to do as much labor around the house.

“She stayed close to my grandma,” Merrilee said.

Although Joyce was never drawn to sports like many of her siblings, she found plenty of other activities that held her attention: dancing, singing, reading and cooking among them.

“She was a homebody by nature, but she liked people and got along with them well. She was quiet and never raised her voice. She could be a tattletale though,” said Kanashibushan, with laughter in her voice.

As they grew up in Roslyn, the Cravens grew accustomed to often being the only Black students in a class of 27 to 28.

While some teachers treated them well, others tried their best to place restrictions on Joyce and her siblings, refusing to grant several of the girls their rightful place as Valedictorian.

While there were blessings to living in Roslyn –having a small, tightknit community, knowing who to turn to for help – the Craven sisters knew early on that Black women wouldn’t be hired for even waitressing or cleaning positions. They’d have to go elsewhere for employment.

The Cravens didn’t let societal limitations, spoken or unspoken, prevent them from pursuing their goals and ambitions.

Kanashibushan wasn’t surprised her sister wanted to be a teacher.

“She had to work so hard for it,” she said, thinking back on her older sister’s experience.

Joyce was one of two students at Central Washington College of Education, now known as Central Washington University. She graduated with three bachelor’s degrees.

“They didn’t hire Black teachers often unless you had light skin. It’s still like that today sometimes,” Kanashibushan said. “She had to go to Portland to work since there were no positions for her in Washington.”

While she considered herself a lifelong teacher and later completed graduate work at Seattle University, Joyce’s work wasn’t only accomplished within classroom walls.

She joined forces with her oldest sister Leola Woffort, to fight for the rights of marginalized and underrepresented populations. They worked tirelessly for Motivated Mothers and defended Welfare Rights in various states.

“My sister won awards for her work in the community,” said her younger sister, Ethel CravenSweet. “She flew all over the country helping people

with their welfare rights. She helped people in the community better their lives.”

Said Merrilee, “My mother was an activist. She saw what needed to be changed and fought for the rights of women and children.”

Joyce’s faithful activism included marching with Dr. King during the Civil Rights Era.

She was also awarded a certificate from Rev. Jesse Jackson for her work with vulnerable populations.

Joyce and her eldest sister, Leola Woffort put their efforts into helping those who were redlined in the Central Area in Seattle between Madison Street (north) and Jackson Street (south). They ensured that more people knew which social services were available to them and where to find them.

“My mother and her older sister were phenomenal,” said Rose-Ethel Finister Harris, Joyce’s youngest daughter. “They were strong women who worked for positive change, not only for people of color, but people, period. My mother was an advocate for the community, and she worked to bring the best changes for everyone.”

Joyce also prioritized the needs of her family. The mother to three: Merrilee Smith, Ricci Greenwood, and Rose-Ethel Finister Harris, and the grandmother to many, she made sure she was available to lend a hand or an ear. Given her strong focus on education, Joyce inspired her children to follow in her footsteps and prioritize their education.

“My mother was very interactive with our studies,” said Rose-Ethel. “She spent three years as the president of the PTA when my siblings and I were growing up.”

All three of Joyce’s children attended the University of Washington.

Accolades, Memories and Joyce’s legacy

“My mother was my first teacher,” said her son, Ricci Greenwood. “Kindergarten at Lafayette Elementary School. I lived under my mother the first 18 years of my life. Her lessons were biblical and glorious.”

Whether it was caring for a loved one after a surgery, singing to the children, or remembering family and friends with birthday cards, when Joyce saw a need,

she rose to the occasion.

There was a quiet strength and boldness about her that lives on. So does her whimsical, sultry side that brought great joy and amusement to those who knew her.

“My grandma knew how to dress,” her granddaughter Chamara said, with a smile in her voice. “She was a flirt, too. People always wanted to help her wherever she went, both men and women. She had a presence when she walked in a room.”

Her daughter Merrilee reiterated her mother’s flair for style, saying that her mother would opt for a pencil skirt over pants on any occasion.

“My mother had a lot of “get up and go,” said Merrilee. “She was walking until she was 87 or 88 and rarely used her scooter. She barely stayed home (in her later years), but her home was a beautiful sanctuary.”

Although she made her home in Washington, Joyce loved to travel and treasured her trips to Jamaica, Germany, and Israel.

Joyce’s younger sister Ethel has fond memories of their activism on behalf of the Roslyn Black Pioneers over the past few decades. In addition to speaking at numerous schools in the Pacific Northwest and teaching students about their family heritage, the sisters spent time assembling floats for parades across the state in the 1980s and 1990s.

“I’ll never forget when Joyce showed off her legs on our float,” said Ethel. “We were wearing shimmering dresses, and at one point, my sisters and I all raised our legs together. The driver saw what we were doing, and he put his skinny, pale leg up too,” Ethel laughed.

“We had so much fun. I didn’t know how to make a float at first. We were facing backwards and should have been facing the people in the crowd, but that didn’t matter. We went into the Kingdome for our Roslyn Black Pioneer Centennial Anniversary in 1988 and were met with a standing ovation,” said Ethel. “In 1990 we won first place at Renton River Days.

Our message was about love, having a dream, and letting people know about the Roslyn Black Pioneers.”

Though it’s bittersweet for Joyce’s family and friends to look back on such memories, her legacy is only just beginning.

“My mother was my best friend throughout my life,” said Ricci. “I have the biggest hole in my heart, which can never be filled. I just hope as I live the remainder of my life, I can be 1/100th what my mother was.”

There’s no doubt in Rose-Ethel’s mind that if her mother was still here, she would be advocating for positive change with the events happening in our nation now concerning criminal justice reform.

“If my mother was still here, she’d inspire people to get out there, be active and affect the change we need,” said Rose-Ethel. “She wants people to be blessed.”

While Joyce’s family is grieving her loss, it’s heartening for them to know that the work she started can be upheld and furthered by future generations.

“Sometimes I think about my great grandmother and my grandmother surviving in this country, and I hear of all they went through, it gives me strength,” said Chamara.

“My grandmother taught me to be committed, loyal, and dedicated. She is someone who kept on going.”

She said she can’t help but think when she sees signs like the beautiful hummingbird outside her door that her grandmother’s presence is with her still.

Editor’s note: This is the conclusion of the Donaldson Family history as told by author Alisa Weis

With a growing family of seven children living in Tennessee, Jessee and Anna Donaldson kept hearing of improved opportunities for African Americans in a small town called Roslyn way out west in Washington state. At the end of the 19th Century, Roslyn was quickly becoming a coveted destination for diverse and immigrant populations. Coal was an ever-increasing energy commodity, fueled by the Northern Pacific Railroad’s expansion. Opportunity abounded for those willing to work hard with long hours. African American labor recruiter James “Big Jim” Shepperson led hiring efforts. Big Jim was also a politician, business owner, and community leader for African American families ready to spread roots west.

Not quite ready to relocate their entire family to the Pacific Northwest, Jessee and Anna made the difficult decision to send their oldest son solo, 13-year-old General. He was (named after Jessee’s friend General Townsend who served with him in the United States Colored Troops 15th Regiment. General was entrusted to scout out the region for them first. Soon after General boarded the Franklin, Wash. bound company train, he was taken under Big Jim’s wing, and the Donaldsons came to regard him as a benevolent family friend. General is referenced by one of his nicknames “James Donaldson” in Ernest Moore’s The Coal Miner Who Came West for the May 1891 passenger record, disembarking in Cle Elum prior to the train’s final stop.

Despite Mr. Shepperson’s valuable aid, the modern-day Donaldsons shake their heads in wonder, envisioning their own 13-year-old family members taking a train across the country. So often kids this age are just coming into their own, taking off on bike rides or starting to go to the movies with their friends. Moving to another state alone full of uncertainty of how you’ll be received for the color of your skin is hard to fathom.

“General inspires me almost as much as Jessee for traveling to Roslyn by himself,” Butch said. “He may have had Big Jim’s guidance, but he decided to travel ahead of his family, and it was a [contentious/difficult time]. They didn’t know they’d be breaking a white coal miner’s strike and issued rifles. Some Black men got off the train rather than [enter the fray]. They were considered “scabs” for being the replacement to white miners. They weren’t well received, and it was a difficult beginning in Roslyn.”

Though recognized for his vast influence as a leader, including his founding of the Black Masonic Lodge, Shepperson remains a

controversial character in Roslyn’s history. He appealed directly to Black families, promising opportunities to own land, but he reportedly failed to mention that they’d be breaking white coal miners’ strikes. When revealed, this intentionally omitted information tempered the enthusiasm of the recruited Black families seeking a better life.

When Black male miners and their families arrived, they were met with an intense and oppressive environment. One telegram sent to Tacoma in December of 1888 details how the “new men were badly used up” and how “mob reign rules in Roslyn tonight.” Families customarily traveled later to join their brothers, uncles, and husbands.

Though some historical accounts tend to gloss over the ease at which Black families were accepted and enabled to earn equal pay, not all accounts mention the first years when African Americans were threatened and treated with hostility. In the first year they arrived, they froze through the winter in inadequate housing and their loved ones were reportedly not even permitted burial in the Roslyn Cemetery (see Coal Town in the Cascades). Organizations like the Knights of Pythias would soon enough form to cover such essential expenses with Mount Olivet designated as the separated African American burial site.

(From left) A man believed to be General Donaldson with his brother George “Sharkey” Donaldson, ca. 1904. Photo courtesy of Al “Butch” Smith

General saw enough potential beyond the shortcomings of this new Pacific Northwest destination that he urged his entire family to join him. General began mining soon after his arrival in Roslyn and survived the deadly explosion that claimed many lives on that notorious day of May 13, 1892. Regarded as Roslyn’s bleakest time to this date, General experienced the dangerous gas filling the air and the subsequent wave of sadness that enshrouded Roslyn in the wake of 45 men killed.

Continued from previous page

One doesn’t have to look too hard to realize General inherited his father Jessee’s persistence and fortitude. Surviving through the town’s tragedy, General continued to work the coal mines and learned the trade of carpentry in his spare hours. He had the support of Big Jim and so did his father. Shepperson’s signature is found on one of Jessee’s many petitions for his pension.

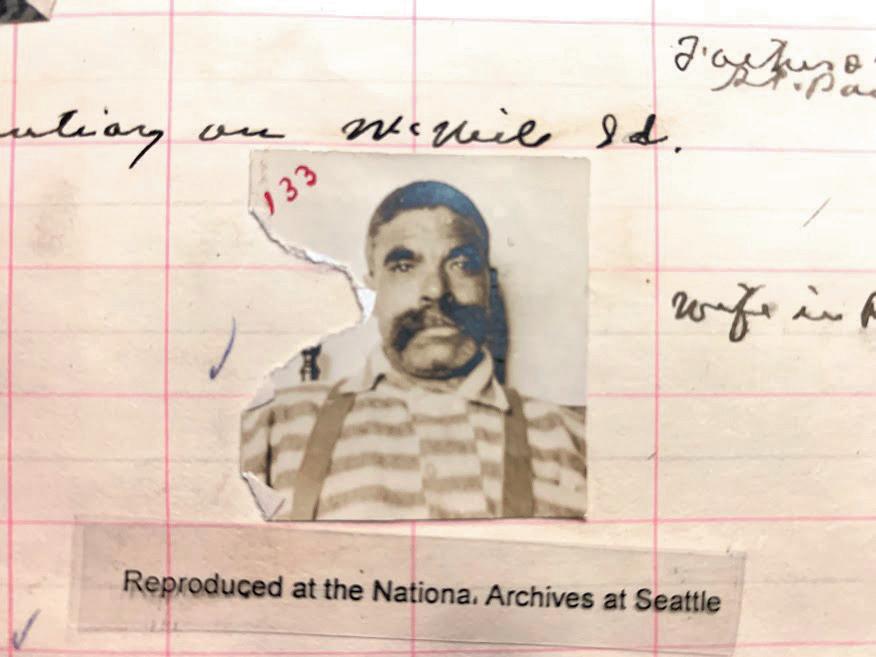

According to his McNeil Island prisoner intake ledger, Jessee Donaldson and the rest of his family finally set out for the land of purple wildflowers, plunging blue waters, and evergreen surroundings in 1894.

In 1897, Jessee realized his dream, becoming property owner of a Roslyn frame house and all outhouses on the south and east of the sixth block. He stepped into the dual roles of coal miner and farmer for the next five to seven years.

It took 15 years for Jessee to receive his first pension check. To obtain it, he’d applied repeatedly, enlisted the testimonies of friends, and endured setbacks from his injuries without it. The musket that had blown up in his face took a lot of his eyesight along with a diagnosis of photophobia. To imagine that he endured this plight and still tunneled below ground with his pickaxe and lamp on his hat for years is humbling. There’s record that Jessee finally received his first pension check for $24 in 1908.

Though living in the Pacific Northwest demanded much of his sweat and toil, Jessee didn’t allow anything to hold him back. He kept one foot in front of the other. What’s monumental about his time in Roslyn is that he was able to put down roots on land that belonged to him. It was a dream fulfilled after 16 years enslaved by his birth father and his white stepmother, his four years of service in the War, three years of jailtime in Tennessee, and more years of waiting until he had an adequate income stream. But life didn’t get easier for Jessee.

He unfortunately lost his wife of 30 years, Anna, to tuberculosis in 1904 and was tasked with raising his children alone. It’s a responsibility he took to heart like all the rest that crossed his path.

One instance of Jessee looking out for his own occurred soon after his son, George “Sharkey,” was injured in the mines.

When he was 19, Sharkey was working as a switcher in Mine No. 2 and was in an accident that injured his leg and his foot. His father filed guardianship of Sharkey’s affairs and obtained his son’s settlement from the Northwestern Improvement Company. Sharkey was awarded $400 for damages caused, and Jessee continued to look out for his son’s accounts until he was 21 years of age.

Sharkey worked the Roslyn mines for years, even after he married his wife, Pearl, and they had three children of their own. Sharkey dabbled in gold mining for a time under his father-in-law’s direction, but his mining years began to wane after his wife’s tragic death, also to tuberculosis. He eventually followed in his family’s footsteps and moved further west to Seattle seeking opportunities.

Though the Donaldsons didn’t remain Roslyn residents beyond the 1910s, the town’s significance is paramount to them. One of the Donaldson’s precious

Jessee Donaldson photograph in McNeil Island Penitentiary Inmate Intake Register, Dec. 17, 1902. Photo courtesy of the National Archives at Seattle

keepsakes is the land deed to the family’s home on First Street and Montana Avenue. A Roslyn map gifted by the Roslyn Ronald Cle Elum Heritage Club is one of the family’s most cherished documents.

Moved by the sacrifices of his ancestors, Ray Donaldson presented a script on Jessee’s life (cowritten by son Ryan and cousin Butch) as part of the Living History Portrayal at the Roslyn Cemetery Kiosk Dedication in June 2021. Donaldson family members made the trip over the Cascade mountains, some for the first time, in honor of this event. For all involved, and it was an enriching experience to return to the stomping grounds of ancestors.

“It’s intriguing to consider what Jessee and Anna endured, but I also can’t imagine it,” Ray said of his family’s determination to forge forward in a society so often opposed to their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Forced to grow up quickly, General forged his own Pacific Northwest path. In 1897, he married Louisa “Ollie” Nicholas-Clark, the daughter of another Roslyn Black pioneer family hailing from Illinois. General learned that the Nicholas family traveled to Roslyn on the same train as he, though he didn’t make their acquaintance until later.

Though skilled at coal mining, General’s first love was always carpentry.

Babe writes in the Red Book that “every opportunity that was made available to him, he would remodel, repair, or build homes. Not only did he enjoy this work, but he was also able to supplement and provide for his growing family.”

General and Louisa were blessed with 12 children. Ray and his son Ryan Anthony Donaldson emerged from this branch. The family house that General built at the turn of the century, called “The Robin’s Nest” still stands in Roslyn today. For those unfamiliar with it, it’s a renovated, painted-blue home available for vacation renters in near downtown.

General sold the home back in 1916 to a Roslyn resident named Eva Strong. General had decided it was time for his branch to move to Yakima to farm. With the demand for coal decreasing in Roslyn, General felt the need to put down roots where he could make more of a living.

Before he took up farming onions, General and his family weathered uncomfortable living arrangements in Yakima. They had to reside in large wooden boxes with tarps for roofs as they awaited ownership of a

new home. His son, Henry Donaldson, later attested to them being warm, but it still took considerable time and patience for the large family to have a more suitable home.

The area where the Donaldsons first lived in Yakima was called “Shanty Town.” In 1918, General found the land for his family to settle. Unable to produce a down payment, he and his family had to stay in tents and rent the acreage until they could save enough money to purchase it. Fortunately, the onion crop of 1920 was so strong that General was able to afford the down payment.

Over time, General owned 20 acres of orchard and 30 acres of farmland. The going wasn’t easy from thereon out, especially as the Depression swept over the nation and diminished the value of farm products. Though General had a surplus of apples on his farm, he sometimes had to dump them when they didn’t sell.

He was forced into the wrenching decision to give up owning his land and work as a ranch foreman for white rancher Harold Cahoon. Through saving up, General eventually was able to purchase the Yakima family home his children had grown up in.

General’s perseverance against the odds —which mirrors that of his parents, Jessee and Anna—is indicative of the resolve that runs in the Donaldson bloodline.

Whereas General traveled east to farm, many Black miners moved west to Seattle and other nearby cities once work in the mines leveled out.

Donaldson Presence in Seattle

It might surprise some to learn that Manuel Lopes, a Black man, made his home in Seattle 10 years before the Civil War. Or that there was an African American man named York who contributed to the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveling down the Columbia River to the Pacific Coast. Or that a Black man named George Washington is responsible for settling Centralia, Wash., with a monument, unveiled last year, commemorating him at Olympia’s Capitol Campus. Or that Nettie Asberry, a Black woman suffragist, was a co-founder of the Tacoma NAACP, the first chapter west of the Rockies. Until recent years, such history was left to the margins of history books if there was a mention at all.

Following the footsteps of these early founding pioneers, the Donaldsons migrated to Seattle at the beginning of the 20th Century.

“There’s a belief that Black people don’t exist in the west,” Dr. Quintard Taylor said at the June 2022 book launch for his second edition of The Forging of a Black Community at the Seattle Public Library. He went on to say, “There are a lot of Black experiences, and they are as valid here as anywhere.”

The Caytons were among some of the most educated people in Seattle regardless of color, and yet they endured the racist constraints put upon them. Together in 1894 they first published the widely circulated The Seattle Republican. Utilizing informants and based on the Caytons’ travels through the area, every issue of their paper included a local Roslyn section, along with other Black pioneer towns and cities. In combing through the succinct summaries, interested family members or researchers can quickly gain insight into lives from the past, including trips, church functions

Continued on Page 10

and special events, as the Donaldsons have had the good fortune to do. Digitized versions of The Seattle Republican can be freely accessed on the Library of Congress website, Chronicling America.

The Caytons with their children composed one of two Black families to reside in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. According to African American historian Ralph Hayes, Dr. Taylor, and others, they lost some of their standing when their publication spoke out against the lynching occurring in other states. As soon as their reporting turned slightly political (emphasizing human rights), their business was made to suffer, with white readers cancelling subscriptions en masse. In 2021, the Cayton-Revels House was designated a City of Seattle Landmark in recognition of the family’s historical significance. The landmarks nomination, written by Taha Ebrahimi, is available online and provides an extensive background and further details on the Caytons and their children.

Though Washington is often hailed as a progressive state, some historical accounts will tell you that the Black tolerance might in part be because the African American population was so small for the first four decades of the 20th Century. There are too many occasions of racial upheaval—the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1888, being one of them—to claim ethnicity had no bearing on where one stood in society. By the onset of World War I and the Great Migration, Seattle had more clearly defined norms for where nonwhite communities could frequent and reside. Prior unspoken “rules” dictated how non-white people could interact, socialize, and marry.

In his foundational work, Dr. Taylor chronicles the African American community from the 1870s through the Civil Rights Movement. He said that the work he does as a historian involves refusing to “propagate American mythology that Black people haven’t done anything in the west.”

One need only look to the online resource center Dr. Taylor he oversees, BlackPast.org, to comprehend the global experiences and contributions of hundreds of people with African Ancestry. With more than 8,000 posts and growing, BlackPast.org provides worldwide access as the largest web-based resource for African American history.

After Seattle’s Great Fire of 1889, opportunity abounded more for some people than others. With an influx of European immigrants moving to the region, competition grew for manual labor and service jobs. John Thomas Gayton, who arrived in Seattle as the coachman to a white doctor and his father at age 24, began his own business as a barber, then worked his way up to being a head steward and eventually a Federal Court Librarian. William Grose, Seattle’s second Black settler, became a prominent hotel and restaurant operator and property owner. While Gayton’s and Grose’s stories were successes, not all Black families experienced such an ascent up the ladder.

Babe’s own father, Henry Donaldson, contributed to a video series called “The Forgotten Pioneers” for the Washington Centennial Ethnic Heritage Project. Airing in 1988 on KIRO, video producer and anchorwoman Nerissa Williams interviewed him about his experience growing up in Roslyn. He

recounts the story of his father, General, traveling west when he was only 13 years old.

“I heard three train loads came out, and my dad came out on one of them,” Henry said. “No. 3 mine was the biggest mine is Roslyn, and that’s where they had all this trouble starting, and that’s when they brought the [Black miners] in.”

For decades coal was the desired commodity, and men toiled long and hard to extract it from the earth. Despite a contentious start where African American newcomers were often threatened, Black and white miners eventually formed a working relationship in the mines. One’s color was not of utmost importance when faced with the rigors of tilling the earth as a team, trying to stay clear from cave ins and other injuries.

As demand for coal subsided and Black families dispersed throughout the state, they found opportunities in other trades. Yet they were often limited by the “powers that be” by how far they could reach, where they could frequent, and where they could reside.

When Henry later lived in Seattle, his business –Donaldson’s House Contracting Co. – suffered from his African American customers facing financing barriers. “We couldn’t get loans or FHAs from the bank,” he said of the widespread discrimination.

There were also spoken and unspoken rules about which people could frequent businesses. For instance, Seattle’s Metropolitan Theater would only allow Black patrons to go to a separate box office and sit in the balcony. It was called “N---- Heaven” at the time. Seattle’s Moore Theatre still has the original segregated side door that once separated access for the theatre’s Black patrons. If a proprietor wanted to open a barbershop, they had to decide Black or white customers — it wasn’t acceptable to serve both.

“I’ve been to a lot of places that refused to serve you,” Henry said. “Of course, if I knew I wasn’t going to be served, I didn’t want to be embarrassed so I wouldn’t go in. You couldn’t go to a lot of shows. You couldn’t sit wherever you wanted to; you had to go where they put you.”

Henry Donaldson purchased a home for his family in Seattle by 1940, but as his daughter Babe tells it in The Donaldson Odyssey, “We were one of the first Black families to move into the neighborhood and were the subjects of racial harassment both day and night. Some of the neighbors wasted no time in putting their homes up for sale.”

This trend of “white flight” is well documented through the mid 20th Century. Lenora Bentley said that her mother was a white woman who claimed she was “mulatto” so she wouldn’t have to explain why she’d married a Black man. Her mother and her aunt, Babe, bought two respective homes in Seattle around 28th Avenue South and Dearborn Street in the early 1950s. She said, “They both looked white. When their husbands, who are Black, showed up later, all the whites eventually moved out.”

Though Seattle is often credited for not having segregated schools, Donaldson family members will tell you integrated schools had more to do with the low percentage of Black students in the region than a sense of justice or progressiveness of the times. African American students experienced unequal treatment from an early age.

Lenora recalls an occasion when her father, whose

skin appeared darker than her own, arrived at her school, doing his job as an employee of Seattle Disposal. As he was on his way out, “Dad hollered at me. When I said, ‘hi Daddy,’ a little white boy said, ‘is that n---- your daddy?”

“I beat that boy up for saying that, and they kicked me out of school because of it,” Lenora said, meanwhile alluding to the fact that her classmate wasn’t corrected for his racist remarks. Not even a slap on the hand.

Butch Smith, son to Isabelle “Izzy” Donaldson and renowned African American photographer Al Smith, recalls what it was like to grow up in the “segregated redline district” of Seattle. He didn’t often consider the limitations placed upon African Americans until realizing that only Black doctors would treat him. He was sixteen years old before he saw a white doctor for the first time.

In reflecting on his father’s photography, which captures the spirit of the Central District Al resided in for all 92 years of his life, Smith said, “He knew down deep what needed to be documented.” He recalls the “magic” of assisting his father with images in the dark room and waiting to see what would materialize. Al couldn’t have known how many of his photographs from his “On the Spot” business would stand the test of time. Some of his photographs are currently on display at the Smithsonian’s traveling “Negro Motorist Green Book” exhibit, as part of the art collection on display at the Jackson Apartments in Seattle’s Central District, and forming part of the Interview Wall at Black-owned Emmy award-winning media company Converge Media’s studio in downtown Seattle.

As evidenced from Smith’s body of work, the Central District night clubs were diverse and integrated. Jackson Street was regarded as the city’s melting pot. In group photos, you’ll find whites alongside Native Americans, Asians, and African Americans. The photographs prove that despite unspoken societal restrictions and active suppression, there were places where interracial acceptance, friendship, and love was revered and encouraged. While photographs taken at community venues such as the Black and Tan Hall don’t eradicate the problems and pitfalls outside those walls, they instead showcase a community willing to disrupt the status quo (Black & Tan Hall | Seattle, Wash. (blackandtanhall.com).

It might surprise some to realize that Washington is the only western state without an anti-miscegenation ban. Whereas there was a short-lived ban on interracial marriage when Washington was a territory back in 1855, the ban was eradicated in 1868, revisited in 1935 and overturned again. But simply because there wasn’t a legal jurisdiction didn’t mean that love across color lines was commonly accepted. The Donaldsons would know, having been a biracial family since the 19th Century.

The current Donaldson elders pay homage to the self-published family history book, The Donaldson Odyssey for connecting across five generations. Without its carefully preserved records, they admittedly wouldn’t know much of where their ancestors’ footsteps across the country had taken them.

“There’s a lot in that book I have no knowledge of,” said Ray Livingston, the oldest of George “Sharkey” Donaldson’s grandchildren. The family’s journey from

Continued from previous page

a plantation home in Alabama to the coal mining towns of Washington State would be lost to him if it weren’t for book author and family member Lillian Babe (Donaldson) Warren’s scrupulous research.

“I read about Jessee in The Donaldson Odyssey that Babe put together. Other than that, I haven’t heard of him.”

Now 86, Ray said that the Yakima he grew up in was a segregated town. Since he grew up with the division, he didn’t pause to think of its racist implications until later. “Strangely enough, I didn’t realize we were being segregated. It didn’t cross my mind.” he said. “But now when people ask me, ‘Was Yakima racist?’ I tell them, ‘You bet it was.”

Of Yakima’s many taverns on First Street, Livingston says he grew accustomed to seeing signs that said, “We cater to white trade only.” If he wanted to attend a performance at Capitol Theater, he was made to sit in the balcony. There were other theaters in Yakima where he wasn’t welcome at all. Because he was a regularly performing vocalist and singer, Ray evaded some of the restrictions placed upon Black patrons. He was allowed to enter in at the stage door along with everyone else.

He does recall an occasion back in 1954-’55 when he won a Yakima singing contest. He and some other performers from surrounding areas like Tacoma, Spokane, and Bremerton were invited on a trip to Hollywood. He, another Black singer named Sammy Pleasant, and four white singers together embarked south on this trip.

“They wanted to set us up at the Hollywood Hilton,” Ray said, “but the promoter turned to Sammy and me and said, ‘you guys can’t stay here.’ The white singers got to stay, but Sammy and I were brought to South Central LA instead.”

Though The Negro Motorist Green Book was in circulation at this time, neither Ray nor Sammy had access to it when they could have used it. For those unfamiliar with it, The Green Book was the manual for travelers of African descent between 1936-1967 who needed to know which restaurants and lodging were inclusive safe spaces.

The Smithsonian traveling exhibit, “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” vividly portrays what some of our American brothers and sisters endured as they faced the caustic realities of Sundown towns and hostile inequalities on the road. Civil Rights in the PNW though the western road symbolizes freedom to many Americans, there are definite reasons The Green Book remained in print until the late 1960s. With over 5% of the population being African American in Seattle, the disparities in jobs, housing, and de facto education became even more visible, and it was tiring to revisit the same restrictions the Civil War’s conclusion was meant to resolve a hundred years before.

The Civil Rights movement sparked by 1963 in Washington state. Committees such as Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) implemented strategies which included, as noted by Dr. Quintard Taylor in The Forging of a Black Community, “negotiation with store managers and direct-action boycotts with accompanying picketing of businesses.” Other influential organizations included the NAACP, the

Urban League, and the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, which assisted non-white people who sought housing outside Seattle’s red-lined Central District. The Donaldson family varied in their involvement and approach to the Civil Rights movement but all attest to its importance.

“I didn’t participate because I couldn’t be nonviolent,” Lenora Bentley said. Unfortunately, an early childhood incident with a white classmate calling her father a racial slur was far from the only brush with racism she experienced growing up.

She recalls an occasion where her parents attended a Communist meeting—the offering of a free meal and drinks enticed—and her father was made to pay for it the following night. She remembers how she and her sister were sleeping on a hide abed in the living room when police officers suddenly kicked down the front door and dragged her father outside.

“I didn’t understand why they had to drag my father—a Black man— in the middle of the night. They kept him for a day. At least long enough for Mama to bring him some clothes. My uncle [Henry Donaldson] came over and fixed the door,” she said, pausing to reflect. “It scared the hell out of us. How our government can drag a Black man. It still bothers me to this day. It really does.”

Lenora said that she saw a lot of good emerging from the Black Panthers, a community organization that a lot of the Donaldson “uncles” were part of. “They were trying to educate our young people. They gave them breakfast, money for lunches and dinners. A lot of older Black people donated.”

Aware of the “dangerous” reputation that attached itself to the Black Panthers so readily, Lenora said, “It wasn’t a violent organization. I don’t feel it was.” Instead, she comprehends how the Black Panthers were necessary to protect people like her father from being signaled out for further injustices. While there are always outliers who detract from the cause, Dr. Taylor suggests that Black Panthers were sometimes written off for their black leather and beret ensemble and inflammatory rhetoric.

He says in The Forging of a Black Community, “Seattle’s Panthers established a free medical clinic, prison visitation programs, a statewide sickle-cell anemia testing program, tutoring programs, and a free breakfast program for impoverished children. They were also credited with quelling random violence and attacks on police and property in the Central District in 1968 and 1969 and participating in dialogue with Asian American business groups in the District through the Seattle chapter….”

One of the many things the Civil Rights Movement did was shatter “the illusion of inclusion” that began presiding over our region since before Washington became a state. Though the work is far from finished—as we hear Henry Donaldson recount in The Forgotten Pioneers— Dr. Taylor concludes “Courageous Seattleites—primarily Blacks but also some sympathetic Asians and whites—had, during the 1960s demolished decades-old barriers to opportunity and equality throughout the city.”

Since The Donaldson Odyssey’s inception, not every Donaldson family member has embraced the knowledge of their Black roots, though most pride

themselves in having an ancestor who showed such unwavering courage and determination as family patriarch and Civil War veteran Jessee Donaldson. Paula said her great uncle’s children were told to “stop acting Black” and that she watched them “being put down for presenting as they really are.” She said that she handed a copy of The Donaldson Odyssey to a cousin and that it “took a while for her to digest it and decide that she wanted to come in.

She was told she was white growing up and later learned she was part of this larger family.” Paula has one relative who has yet to reach back after being told of her Black ancestry, saying “she is probably comfortable with who she is being white, but she probably knows in the back of her head” there’s more to her story. Not everyone from Jessee’s direct bloodline visually presents as African American, but they still closely identify with their Black ancestry and celebrate it.

“We have a number of people like Ryan and myself who don’t look Black at all,” family member Al “Butch” Smith said, adding that he has a biological sister who has dark skin, both of whom are the children of Al Smith Sr. and Isabelle “Izzy” (Donaldson) Smith. “There are a few of us who essentially look white, but don’t identify as white. We pass in the context of white privilege since people don’t know our history.”

“We’re a proud family,” Paula said, reflecting the various shades that comprise the Donaldsons, Bentleys, and Livingstons. “I love all the different dynamics. I embrace every aspect.”

While much is already researched and written on them, the Donaldsons continue charting their family’s legacy. More than a dozen Donaldsons attended the 44th annual Roslyn Black Pioneers Picnic in August 2022. They cherished the opportunity to exchange stories of their Roslyn roots with the Cravens, the only original Black pioneer family who still resides in the coal mining town. The picnic has a celebratory tone every year, yet there’s also seriousness to the time when ancestors are spoken of and remembered with respect.

The Donaldsons are writing a narrative account expanding on Jessee and Anna’s lives. Built upon the foundation of The Donaldson Odyssey, this new account will include additional details that have been discovered with an intended audience of intergenerational family members. It is important for each generation of Donaldsons to understand their Alabama and Tennessee roots. They also want to research the white Donaldsons prior to the Revolutionary War.

Lenora said, “I want to know more about our white side. Who were they? What kind of people were they?” Ryan echoed her sentiment, saying “I’ve wondered about them too. With [my wife] Lori’s parents living 30 minutes from the original planation in Hazel Green, Ala., we went to visit it. While we there, we came across some of Levi and Charlotte’s line, and we paid our respects at the gravesite. We wanted to center our Black relatives first and [though it’s still our focus], we are interested in knowing more of the white side.”

Tia Juanita Jackson, one of Jessee and Anna’s descendants, said that she revisited The Donaldson Odyssey a year ago and that the work Babe did on

Continued on Page 12

Continued from Page 11

it is extraordinary. She wouldn’t have known about her Alabama roots without the anthology. If there’s anything left to uncover, Tia said she’d like to know more about matriarch Anna and the women who followed in her footsteps.

“The women in our family are strong. I’d love to know more about Anna and see where that gene came from. I’m curious to know how she lived her life. There’s a church characteristic that runs through out family. I have distinct memories of going with Aunt Lenora and Aunt Babe, and it [appears] evangelism is woven into our fabric. I don’t know much about the women, the sisters in our family, and I’d really like to.”

Since made aware of the verified image of his five times great-grandfather, Ryan said his impression for what Jessee endured has deepened considerably. The photo depicts Jessee on the day of his arrest in December 1902, decades after fighting for his freedom with the United States Colored Troops in the Civil War.

Upon seeing the image of Jessee for the first time ever this July, relative in-law Vernon Jackson couldn’t stop marveling over the uncanny resemblance Jessee shared with Jessee’s son, George “Sharkey” Donaldson, a man he said, was “tall, handsome, always chewing tobacco and carrying a Folgers can around. He was a wonderful man and treated us real good.”

Ryan said “I thought about how Jessee had to spend Christmas without his family. The sensitivity in his eyes amidst another episode of indignity in his life. How Jessee’s life literally shows the connection between enslavement to the development of prisons in the

photo from the 2016

Paula Terrell photo

United States. Seeing through his body posture the physical pain and injuries he sustained. I am astounded that Jessee summoned the strength and fortitude to work the difficult and dangerous labor in the coal mines in Roslyn.”

Ryan said its bittersweet knowing that this verified photo came from Jessee’s incarceration. He wishes the circumstances were different, such as the photo of Jessee attending one of his children’s weddings. “I also recognize how rare it is for us, as an African American family, to even have a photo of our patriarch, a man who had been born enslaved in 1846 and had passed on in 1913. Many families do not have any photos of their

From Old Country to Coal Country

A story of determination and bravery

By Marcy Bogachus

These are the key words behind these collected stories of life in Roslyn, Ronald and Cle Elum in the Central Cascades foothills of Washington state. These small towns remind our families of the lands they left in Europe. Amid hardships and happy times, here are some of the stories we strive to preserve for future generations. Author Marcy Bogachus compiled these firsthand accounts for the Roslyn, Ronald, Cle Elum Heritage Club to produce this book as a fundraiser.

Learn more about our vision at rrche.com

enslaved ancestors.”

Despite reflecting on the gravity of Jessee’s experiences, Ryan and his family see with Jessee’s photo a renewed a sense of purpose and hope. Jessee rose above his circumstances at every turn, and he never stopped advancing toward the life he and his family desired. It’s time more people knew his name. In a letter from Babe to the Roslyn Museum, Babe summed up the overall goal carried forward today, for the Donaldsons “to take their rightful place as part of the history of Roslyn,” joining alongside their fellow Black Pacific Northwest pioneer families, including the Cravens, Barnetts, Breckenridges, Taylors, and Harts.

Ronald Remembered

The tale of living in a small, close-knit town

By Marcy Bogachus

Marcia “Marcy” Minerich was born in the small town of Ronald in 1940 when doctors still delivered babies at home.

Then a town of 300 people, Marcy grew up knowing every single one of them. Growing up in a close community, the memories are more precious.

Working and maintaining their hay farm and raising their two daughters, Kimilee and Renee, kept them busy though the years. They also have one grandson, Weslee.

“As you grow older, the more you think back of your “growing-up” years and the more your heritage means to you,” quotes Marcy. “Remembering Your Heritage has been my motto.”

Aricka Webb is originally from Modesto, Calif., but was raised in a very small town of less than 400 in Maryland. She moved to Washington state almost 11 years ago and eventually settled in Kittitas County.

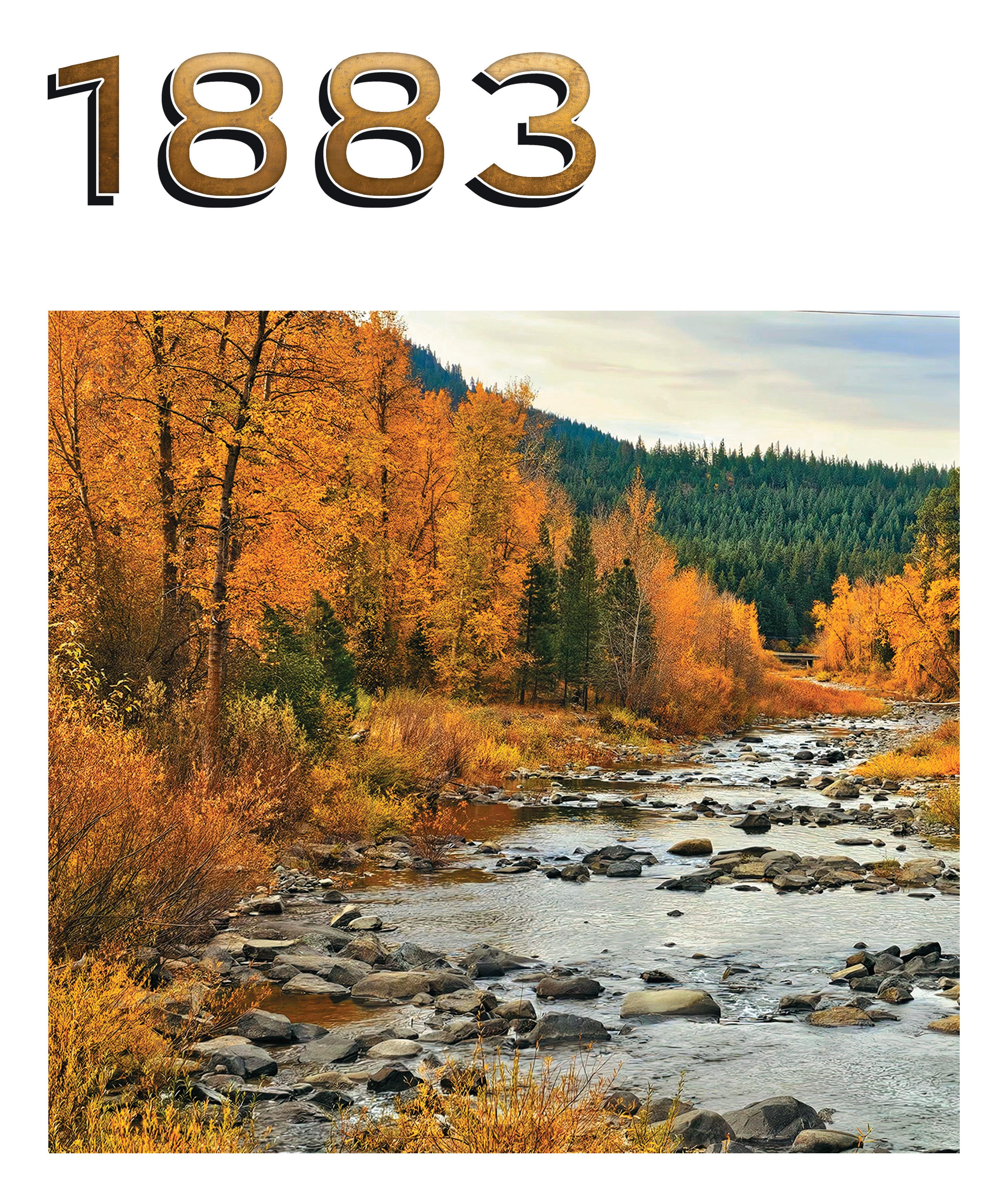

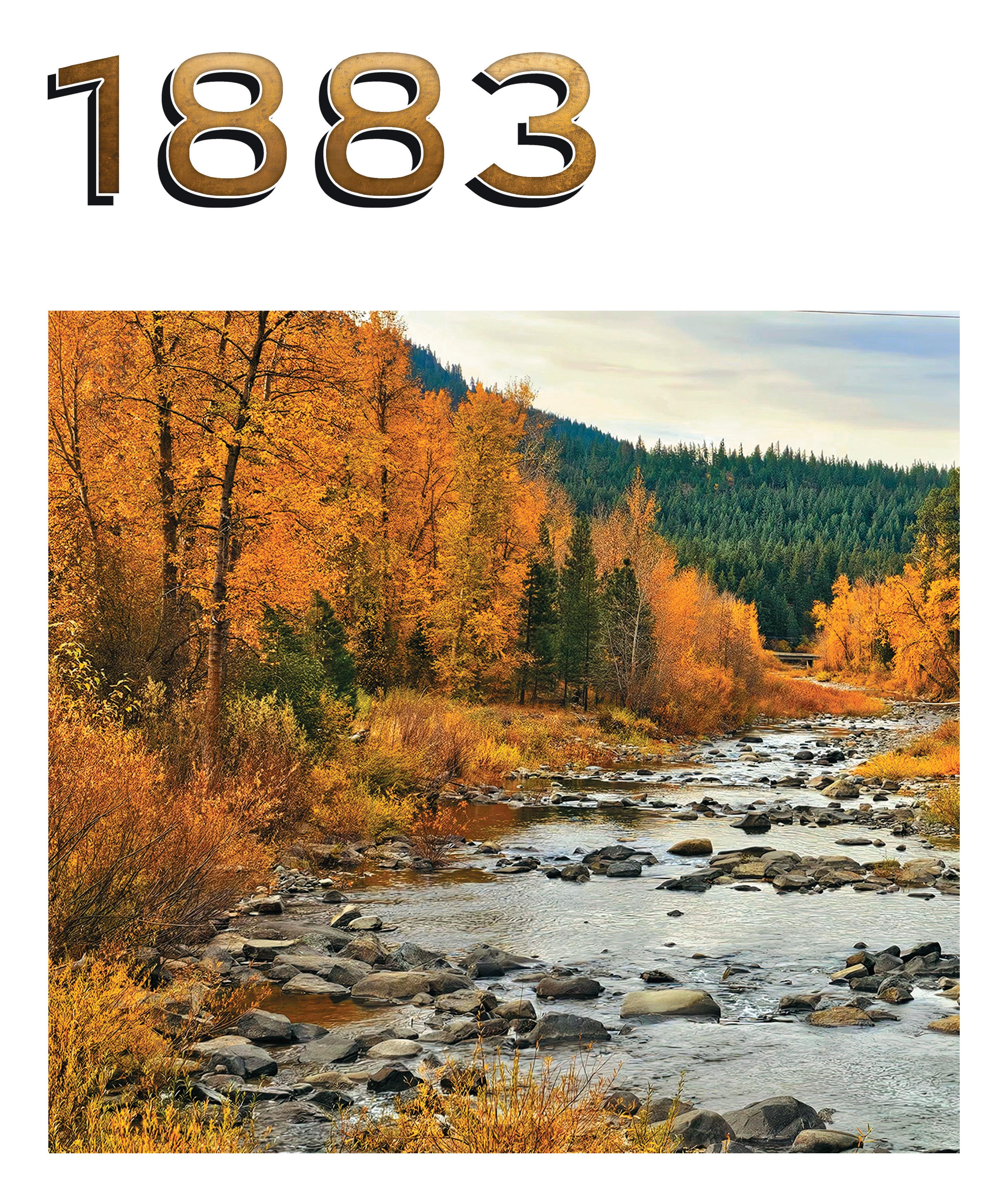

Webb has two children — a girl, 17, and a boy, 20. Her favorite place to photograph is Kittitas County saying, “It doesnt matter where — every corner you turn in Kittitas County has something beautiful. My addiction is what brought me to Washington, and more so, what has brought out the talent in me. My biggest reason for taking pictures and sharing is to inspire others and my hope is to reach others struggling and get them out into nature and to see how much nature heals. But at the end of the day my addiction is how I found my talent. Some say there’s no place like home, I say home is where the heart is. I’m finally home.”

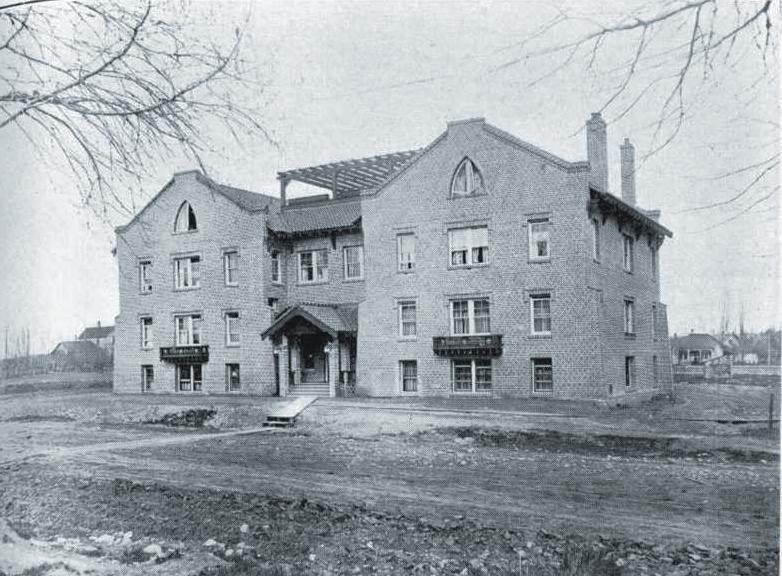

If one were to pick a building on the Central Washington University campus that would be haunted, Kamola Hall would certainly be among the top candidates. For one thing, it’s old and historic, which is usually a criteria for haunted places. For another, as a residence hall throughout its existence, it’s housed thousands of students as well as faculty and visitors—so plenty of potential ghostly patrons.

The more-or-less straight history of Kamola is that the structure was built in 1911 as the first student housing complex (prior to that, students lived in housing in the community). Its original name was simply, “The Dormitory,” which was changed in 1916 to Kamola Hall.

The name change was suggested by Andrew Jackson Splawn, a local historian and one of the earliest residents of Ellensburg. He wrote a letter to the school requesting the dormitory be named to honor Kamola (also spelled Quo-mo-la or Quo-mallah), the favorite daughter of Chief Owhi, once the principal leader of the Kittitas band of the Yakama Nation.

In 1858, Chief Owhi was killed while escaping from military custody. He had been a key figure during the Yakama Indian War of 1855 and a signatory of the Treaty of Walla Walla. His daughter was believed to have been born in 1843 and died in the mid-1860s.

In an article in the March 14, 1934 Campus Crier CWU’s student newspaper, Splawn’s widow explained the origin of the name. She said the chief’s daughter did not originally have a name. One day, her father held her up to a rose and said, “Kamola.” Pleased with the sound and connection he saw between his daughter and the flower, he announced that would be her name.

“The word has no Indian meaning so far as we can discover, but Kamola came to be a prominent figure in their history,” the article said. “Wise in council, she was consulted by both her father, Chief Owhi, and her husband, Chief Moses. She was undoubtedly a remarkable Indian woman, for when she died she was mourned by the whole valley and, tradition says, was given the largest and most impressive funeral ever accorded to any Indian woman.”

The building named for Kamola was expanded in 1913, 1915 and 1919 to meet the growing demand for more student living and dining space. Architectural historian Lauren M. Walton described the design of the building as proto-Modernism styling with Spanish Colonial Revival influences and a touch of Gothic Revival. This design template was later also utilized in the construction of Sue Lombard Hall and Munson Hall.

Kamola was restricted to female residents during its first three decades. Between January 1943 and June 1944, the female students

previously housed in Kamola were relocated to Munson Hall so the dormitory could serve as housing for U.S. Air Force training at the college. Following the war, the building reverted to being a women’s dormitory. It did not become co-ed until 1974.

In 2003-2004, the building underwent a $10M renovation, to ensure it could continue to serve as a student housing facility well into the 21st Century. Stories about Kamola Hall hosting a spectral resident or two didn’t begin appearing until the early 1980s, when the building was converted annually into a haunted house during Halloween. For years, residents dressed up the hallways and rooms with creepy cobwebs and other scary imagery to frighten their fellow students and children from the community.

In 2003, the CWU Observer student newspaper quoted an alumnus, Evan Sylvanus, who claimed Lola was simply a ghostly character concocted in about 1982 to promote the building’s haunted house evenings.

According to the most prevalent Lola “legends,” Kamola is said to be haunted by the ghost of a deceased Central student named “Lola.” Apparently, sometime in the 1940s, Lola (last name allegedly Wintergrund, according to some sources) is said to have died of a broken heart or hung herself while garbed in her white wedding dress.

This tragedy, which happened either in the attic or from an upper floor of the dorm, occurred after she learned of the death of her sweetheart or husband during World War II. Interestingly, the university’s records indicate no one named Lola ever died in Kamola at any time—and, of course, women were not living in the hall during the early 1940s.

Despite the dubious origins of the story, the most compelling argument for there being something supernatural about Kamola came in the early 2000s. CWU’s then-official photographer, Richard Villacres, was tasked in 2002 with taking a moody photo of a female student dressed in a 1940s white wedding gown for a story about

the building’s renovations. As he later explained, he was trying to create an image that would reflect the ghost stories about Lola.

Speaking in 2009 to the Ellensburg Daily Record, Villacres said, everything went fine with the photo shoot, but strange things began to happen when he developed the film.

“I shot three rolls of film inside Kamola of my model and the three rolls of film that I shot inside—two of them came out black, nothing—which has never, ever happened to me,” he said. “The one roll that came out had all kinds of bizarre fogging and weird marks on it. Especially one that was taken in the hallway inside. There is this ghostly figure in the background—all this weird effect is on there. I had no explanation for that.”

Villacres told the newspaper that he sent the film back to the manufacturer, Polaroid, to see if anything was wrong with it and the company found nothing. He said other photos he took that day came out just fine. He used the same camera on a subsequent shoot and, he said, everything worked fine.

“She [Lola] screwed with my film and, honestly, I have no explanation for it,” he told the Daily Record. “Something weird happened.”

There have also been reports of residents in Kamola hearing strange music in the building, of elevators opening and closing for no reason, and cold gusts of wind in places without windows. Some have claimed to have seen ghostly apparitions wandering the hallways.

In recent years, the legend of Lola of Kamola has gained momentum, appearing

on nearly a dozen haunted places websites and blogs, and on ghost-hunter videos on YouTube and TikTok. In an Aug. 29, 2009 entry on the www.ghostandcritters.com blog, a person named “Ivy” said that a few years earlier she had stayed in a room on the fourth floor of Kamola Hall for week in the summer and it “is most definitely haunted.”

Ivy said that during her time in Kamola several weird things occurred including hearing a knock on her door, only to open it and find no one there, and walking through a space in a hallway where she suddenly couldn’t move and was overwhelmed by feelings of dread. She also found the light in her room turned on, after she knew she had turned it off when she had left earlier that day, and her room key mysteriously moving from where she left it to other places in her room.

Is Kamola Hall haunted? That’s difficult to determine based on the conflicting evidence. Perhaps the right question to ask is: would you spend a night there?

— Richard Moreno is the author of 14 books, including Frontier Fake News: Nevada’s Sagebrush Hoaxsters and Humorists and the forthcoming Washington Historic Places on the National Register. He is the former director of executive communications at Central Washington University and was honored with the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame Silver Pen Award in 2007.

By Rich Moreno

“The Boys of Riverside: A Deaf Football Team and a Quest for Glory,” by Thomas Fuller

New York Times reporter Thomas Fuller tells the story of an all-deaf high school football team’s journey from underdog team to an undefeated season. The remarkable tale began in November 2021, when Fuller received an email from the California Department of Education detailing how the California School for the Deaf in Riverside, a state-run school with only 168 students, was enjoying an undefeated football season. Fuller,

who had covered wars, wildfires, and mass shootings, became captivated by their story. During the gloom of the pandemic, it was an uplifting story about a group of underestimated boys and their tireless coach, a former deaf athlete himself.

“Guide Me Home,” by Attica Locke

This latest book by Attica Locke is the final chapter in the award-winning Highway 59 trilogy. Named one of the best books of the year by the Washington Post and National Public Radio, “Guide Me Home” features Texas Ranger Darren Mathews, who is pulled out of early retirement

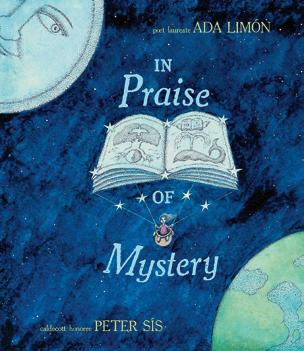

A Poem for Europa,” by Ada Limón (author) and Peter Sis (illustrator) (Ages 4 to 8)

U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón and Caldecott Honoree Peter Sís have crafted a compelling picture book focusing on a poem that is currently traveling through space aboard NASA’s Europa Clipper ship. Limón was invited by NASA to write the poem, which was engraved on the spacecraft, which took off to Jupiter and its moons on October 14, 2024. The book celebrates humankind’s endless curiosity, asks us what it means to explore beyond our known world, and

shows how the unknown can reflect us

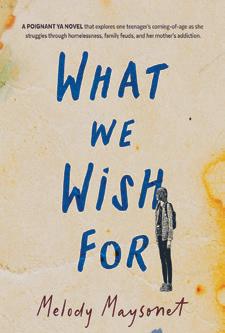

“What We Wish For,” by Melody Maysonet

“What We Wish For” is a poignant YA novel that

struggles through homelessness, family feuds, and her mother’s addiction. The story’s protagonist is 15-year-old Layla Freeman, who tries to pretend her life is fine, but her mom has substance abuse problems and they live in a homeless shelter. After her mother suffers a relapse, Layla is sent to live with rich relatives, where she begins to make new relationships, and thinks her dreams may come true, until a secret threatens come out that will turn her world upside down--and destroy her entire family.

Did You Know?

• The Ellensburg Public Library hosts a Spanish and English Conversation Club that meets Mondays from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. on Mondays in the Hal Holmes Community Center Kittitas Room. All learning levels are welcome and the meetings are free and open to all.

Located about two miles southwest of the Thorp Fruit and Antique Mall, the Thorp Cemetery sits on a lonely rise surrounded by green, open fields, and with a spectacular view of Thorp Cliffs and the Stuart Range. Near the center of the cemetery are two tall trees and at the entrance is a brown wooden sign that spells out the cemetery’s name and the fact it’s part of the Kittitas County Cemetery District.

Wandering through the neatly-groomed burial grounds, you can see hundreds of headstones of various sizes and shapes. The oldest grave dates back to 1878 (Mary Agnew, who died at the age of 38), while the newest is fairly recent since the cemetery remains in active use. According to records, the land for the cemetery was donated by a farmer, Herman Page, a native New Yorker who homesteaded the area in 1875 (he is buried in the cemetery).

Sometime in the 1880s, the three-acre cemetery became the property of the Thorp Methodist Episcopal Church and was apparently operated by the Thorp chapter of the Odd Fellows Lodge until 1940, when the chapter dissolved. In 1962, it came under the management of the Kittitas County Cemetery District No. 1.

So, why is this picturesque but fairly typical rural cemetery considered haunted? No one is certain when the story first appeared, but apparently sometime in the past few decades websites devoted to paranormal activity and ghost stories started recounting how the Thorp Cemetery was one of the most haunted burial grounds in the state.

In each telling, the cemetery was apparently the site of a tragic event. Sometime in 1890, a Native American woman named “Suzy” was lynched on or near the cemetery. Since that time, visitors to the cemetery have reported seeing, on moonlit nights, a ghostly Native woman riding on a big white horse through the headstones. It’s also been reported that the figure has been seen weeping or sobbing in front of the tombstones.

“Thorp Cemetery is one of the most haunted places in Washington state,” notes the website, Washington Haunted Houses. “Located in Kittitas County, the town of Thorp has been documented for its conflicts between Native Americans and American settlers.”

In spite of that latter characterization, it is unclear what conflicts between Native people and settlers from Thorp would still be occurring by 1890. The town of Thorp wasn’t organized and plated until 1895, although John M. Newman and Sarah Isabel Newman homesteaded the land that would become Thorp a few years earlier, in 1882.

The Thorp region, and the rest of today’s Kittitas County, was the home of the Kittitas tribe prior to the arrival of white settlers in the 1860s. About a mile from the current town of Thorp was an ancient indigenous village called Klála that was one of the largest in the valley, which was said to be rich in wild berries, fish and game.

In addition to Newman, other white settlers who came to the area included the Fielden Mortimer Thorp family and Frank Martin. When the townsite was established, it was named after Mortimer Thorp, as he was called, who previously lived in Goldendale and then had homesteaded at the head of Taneum Canyon and was recognized as the first permanent non-Native American settler in the valley. By the 1870s, the future site of Thorp was known as Pleasant Grove.

In 1872, a post office was established at Pleasant Grove. By then, most of the native population had dispersed or been moved from the valley to the Yakama Reservation under the terms of the Yakama Nation Treaty of 1855. Under that agreement, the 1.3 million-acre Yakama Reservation was established, but in return the tribes were forced to cede 11.5 million acres of their traditional lands in what would become the state of Washington to the United States government.

The impetus for creating the town of Thorp was the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railway, which in the late 1880s, built a line through the Kittitas Valley, including Thorp. The completion of the hydropowered North Star Mill in 1883, which later became known as the Thorp Mill, had created a product (flour) that the railroad could transport to other markets.

The three-block town of Thorp soon began to develop around the train depot and the railroad’s maintenance facilities, shipping facilities, and warehouses.

According to the “Illustrated History of Klickitat, Yakima and Kittitas Counties,” published in 1904, “Thorp is a substantial and prettily situated farming town of perhaps 200 inhabitants . . . The main line of the Northern Pacific railroad passes through the town, affording excellent transportation facilities and making it an important shipping point for the upper Kittitas Valley.”

While there were occasional conflicts between the settlers and indigenous people in the mid-19th Century, by 1890 such clashes would have been a thing of the past. Which brings us back to Suzy, the ghost of a hanged Native American woman who is said to wander through the Thorp Cemetery. A review of Ellensburg’s historic newspapers or local histories reveals no mention of any lynching ever conducted in or near Thorp at that time.

Did it really happen or is it just a ghost story to be told around the campfire on a warm summer night? In the end, it’s difficult to know the truth. But if you head out to the Thorp Cemetery at dusk, while the shadows of the tall trees are lengthening over the surrounding gravestones, and listen hard, you just might hear something that sounds at least a little bit like moaning—or perhaps it’s just the wind. — Rich Moreno

By Matt Boast General Manager

Kittitas Public Utility District No. 1

As we move into the final quarter of 2025, I want to take this opportunity to update our customers and community on the work your public utility has been doing this year. Kittitas PUD No. 1 remains committed to our mission: to provide safe, reliable, and affordable electric service while planning for the future needs of our county.

Wildfire Mitigation and Safety

Wildfire risk continues to be a top concern for utilities across the Northwest, and we are no exception. In 2025, we have taken several key steps to implement our Wildfire Mitigation Plan:

• Expanded tree trimming and vegetation management efforts to increase right-of-way clearance and reduce fire risk.

• “Non-reclose” settings on our protection systems from June through October reduce the chance of utility-related wildfires. This does, however, mean longer and potentially more frequent outages when they occur, as linemen must patrol before restoring service.

• Planning for “non-expulsion” fuses in fire-prone areas, with installation expected to begin in winter due to high regional demand.

• Undergrounding power lines in select high-risk remote residential areas, a major long-term investment in safety.

Investing in Reliability: Capital Projects for 2025 and beyond

Our capital projects this year and next represent the most ambitious efforts in recent memory. These include:

• Feeder Tie Upgrade between Bettas and Teanaway Substations

This project dramatically increases system redundancy for customers in the Upper County, enhancing reliability and reducing potential outage duration from up to 18 hours to under 4 in many cases.

• Automated Metering Infrastructure (AMI) Rollout

We are transitioning from our “fly-by” meter reading system to a real-time, two-way communication network. This upgrade enhances efficiency, improves outage response time, and provides detailed data on system performance.

• Ellensburg Substation Modernization

Built in 1958, the current station has served us well but needs to be updated. Design and equipment procurement are underway in 2025, with energization expected in 2028.

• New District Service Center Design

After more than 50 years at our current site, we’re preparing for a move. Our newly acquired property on Kittitas Highway will provide the space and functionality we need for the future. Construction is targeted to begin in 2026.

Additional projects include replacing aging transformers, poles, and conductors, upgrading vehicles and equipment, and expanding wildlife protection measures like bird guarding.

Staffing and Training

We’ve had several key staff changes last year, including retirements and resignations. We have since filled the roles of Controller, Engineering Manager, and Auditor. Our focus remains on ensuring a smooth transition with comprehensive training for new and existing employees—so we continue to deliver excellent service.

In compliance with Washington’s Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA), we are updating our 2022 Clean Energy Implementation Plan. This roadmap ensures we are doing our part to support a cleaner, more sustainable energy future.

The district continues to invest in energy efficiency across all customer sectors. We offer a variety of programs designed to help residential, commercial, and irrigation

customers reduce energy use and lower their bills. These include incentives for lighting upgrades, HVAC improvements, energy-efficient appliances, and irrigation system enhancements. By supporting these efforts, we not only help our customers save money but also contribute to a more sustainable and resilient energy system for Kittitas County.

Commitment

As a publicly owned utility, we continue to uphold the highest standards of transparency, accountability, and good governance. This includes full support for state and federal audits, public reporting, and compliance with the Open Public Meetings Act and Public Records Act. The district board of commissioners have regular public meetings on the last Tuesday of each month. Customers and members of the public are welcome to attend. A virtual option is available if people are unable to attend in-person.

The district continues to evolve in response to changing technology, climate, and community needs. We are proud of the progress made in 2025 and are excited about what lies ahead. As always, I thank you for your trust and support as we work to remain the premier energy provider in Kittitas County—delivering reliable service at the lowest possible cost.

Sincerely,

Matt Boast General Manager

Kittitas Public Utility District No. 1

Have you ever heard the story of The Red Pickle?

You may know it as a cornerstone of Ellensburg, with delicious burgers, tacos, cocktails, fresh seasonal specials and more. But owner Mario Alfaro’s journey to Ellensburg—and the story of The Red Pickle—started with love and a dream.

Alfaro, originally from Guatemala, met the love of his life while working at a restaurant in Washington, DC.

“I saw her, and then, you know, I feel like it was an instant moment love,” Alfaro said. “She’s from Ellensburg, so that’s how we started, because of her.”

Nea Charlton, now Nea Alfaro, and Mario decided to move to the West Coast after discovering Nea was pregnant with their first child. They moved back to be closer to Nea’s family. From the first time he saw Ellensburg, it was somewhere he wanted to live.