6 minute read

Picturing Terror

from GR310_Final_Peggy

by Peggy Lin

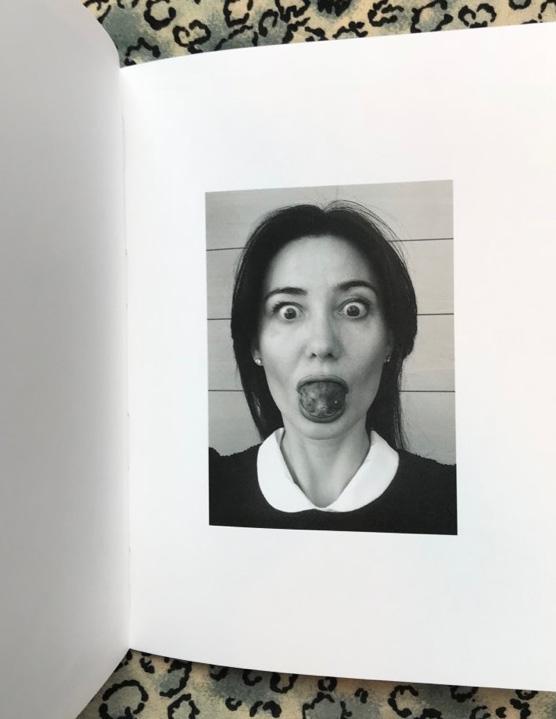

Bassel Barhoum hugs his mother, Jamila Marshid, during his brother’s funeral in the village of Daquqa. Abu Layth died while fighting for the Syrian Army, Latakia Province, Syria, 2013, Andrea Bruce

The tension between terror and beauty has existed at the heart of photojournalism since its inception: it is a practice that originates from recording conflicts through a medium that is intrinsically aesthetic. As the philosopher Walter Benjamin put it, photography cannot delict’s tenement house or a refuse heap without transfiguring it’

Advertisement

The most groundbreaking photojournalism of the 20th and 21st centuries offers a harrowing documentation of some of history’s most terrible conflicts, human rights abuses and environmental disasters. To quote Susan Sontag, from her seminal book Regarding the Pain of

Others, photographs can never simply be ‘a transparency of something that happened’ because ‘to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude’ (2003). Ultimately, they are the authored works of the photographers who took them: subjective documents of history for which lighting, composition and subject matter have all been taken into account. Here, acclaimed photojournalists Andrea Bruce, Giles Duley and Lynsey Addario shed light on how they have negotiated photographing a moment of terror as documentarians, using what is, unavoidably, an artistic medium.

Khouloud and Jamal, Bekka Valley, Lebanon, 2014, Giles Duley

Lynsey Addario

Lynsey Addario is an American photojournalist who regularly works for the New York Times, National Geographic, and Time Magazine. Over the past 15 years, Addario has covered every major conflict and humanitarian crises of her generation, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Darfur, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, South Sudan, Somalia, and Congo. In 2015, she released her first book, It’s What I Do, which chronicles her personal and professional life as a photojournalist coming of age in the post-9/11 world and went on to be a New York Times bestseller. In the same year, American Photo magazine named Lynsey one of the five most influential photographers of the past 25 years, writing that ‘Addario changed the way we saw the world’s conflicts.’ When she’s not travelling, she lives in north London with her husband Paul and their six-year-old son Lucas. I remember walking into Kahindo’s hut, and seeing her in the light of the window, shrouded in a mosquito net with her two small children who had been born out of rape. It was so incongruous—the painterly beauty of the three of them sitting there, juxtaposed with the horrific story she then relayed to me. She was one of the countless victims of the ongoing civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2008: Kahindo had been kidnapped and held captive in the bush for almost three years by numerous Interahamwe soldiers who violated her again and again. I was documenting rape as a weapon of war in the DRC with my first ever grant, and spent two weeks criss-crossing the remote villages of North and South Kivu, where death, torture, and rape had become so commonplace, the better part of the population was palpably traumatized. The brutality of rape is difficult to capture in a still image. With a photograph,

Kahindo, 20, sits in her home with her two children born out of rape in the village of Kayna, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2008, Lynsey Addario

a photographer is often trying to evoke something that happened in the past, and the pain and horror of that moment are present only in a survivor’s testimony, in her posture, her gaze. It is human nature to turn away from brutality, so I try to use light color and beauty to lure the viewer into the horror of reality; an average of 400 women per month were estimated to be sexually assaulted in the autumn of 2007 in eastern Congo. People often look at this image of Kahindo, and comment on how beautiful it is: they assume it is a simple portrait of a mother and her children. And then they start asking questions, and I realise. I have done my job by opening the door to Kahindo’s testimony.

The brutality of rape is difficult to capture in a still image. With a photograph, a photographer is often trying to evoke something that happened in the past, and the pain and horror of that moment are present only in a survivor’s testimony, in her posture, her gaze. It is human nature to turn away from brutality, so I try to use light, color, and beauty to lure the viewer into the horror of reality: an average of 400 women per month were estimated to be sexually assaulted in the autumn of 2007 in eastern Congo. People often look at this image of Kahindo, and comment on how beautiful it is: they assume it is a simple portrait of a mother and her children. And then they start asking questions, and I realise, I have done my job by opening the door to Kahindo’s testimony.

It isn’t the beauty of war that I attempt to capture. It is the beauty in humanity’s attempt to survive and love.

Andrea Bruce

Through documentary photography, Andrea Bruce brings attention to people living in the aftermath of war. She is a co-owner and member of the photo agency NOOR. For eight years she chronicled the world’s most troubled areas as a staff photographer for the Washington Post, focusing particularly on the conflict in Iraq, before going freelance. She has been the recipient of numerous awards including top honors for the White House News Photographers Association and has exhibited internationally. In Syria, working for the New York Times, I photographed a funeral: a Syrian lieutenant had died in the war. To get there I was granted a visa and escorted by the Syrian regime, Assad’s regime, which is seen as an enemy to many in the US. Fear is pervasive in Syria. There is fear of the government, fear of militias and a fear of backlash—of minorities and majorities. Of the other. No one is immune from the fear. The entire village gathered at the family’s house on their way to the funeral. He was the village’s first son, killed for a cause from which the village is far removed. I photographed the mother’s loss and his brother’s rage. These were things I knew people in the US could understand, regardless of their politics. As a photographer, my job is to bridge the differences that are so often amplified in war. It’s our shared humanity that I want people to see. The beauty of love’s darkest form, loss, suffered on both sides in war. War is rarely black and white, though we would like it to be. The people fighting are rarely the people determining a war’s path. Susan Sontag wrote in her book, On Photography, that’ what determines the possibility of being affected morally by photographs is the existence of a relevant political consciousness.’ But emotional consciousness, empathy, is far more universal and can impact a person even in the absence of a political consciousness. Our eyes are drawn to beautiful light and composition but powerful emotions leave an impression and shake the conscience. Photography is an imperfect form. But it is the best medium to bring people closer to reality, make the invisible seen, and help people see themselves in others. Without beauty, few would pay attention. And beauty, as I see it, happens in everyday life. The glance of an eye. The caress of a cheek. Light, color. The combination of movements like a dance, frozen in a toast or a touch. Some say that war photography often mimics paintings of the past. But I believe the paintings of the past simply mimic the grace of violence— in its chiaroscuro shades and layered compositions—of everyday life. Everyday life that happens within war and without.