10 minute read

Changing Faces

from GR310_Final_Peggy

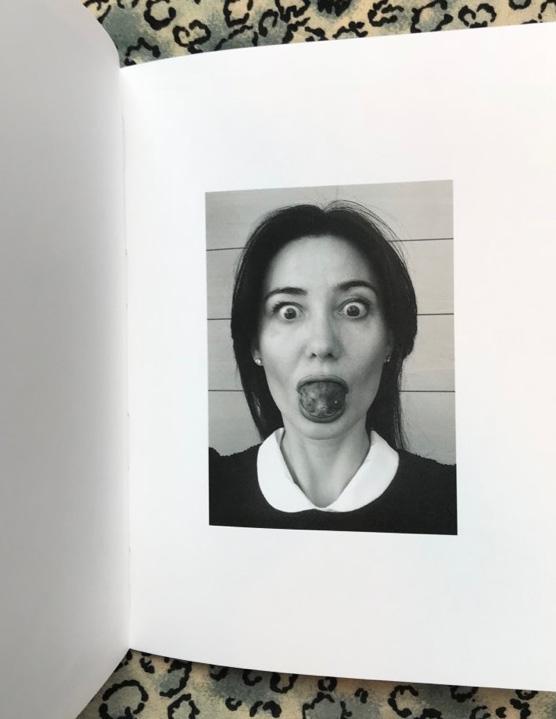

by Peggy Lin

Faces Changing

We attribute great significance to faces. In Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through The Looking Glass (1871), Humpty Dumpty warns Alice that he might not recognise her if they should meet again, because her face is so regular. If her features were more creatively arranged, he reasons, that would make things easier. Blonde, symmetrical Alice looks at him aghast. ‘But it wouldn’t look nice!’ she protests, to which Humpty Dumpty replies, ‘Wait till you’ve tried.’ On this side of the looking glass, we all try to look different from time to time, with varying degrees of success. But being different naturally, or being rendered different by an accident or condition, is another thing entirely. Despite our attempts to be perceived as unique, for the most part we all fit somewhere within the bounds of aesthetic ‘normality’. At this point I should probably note that I’m one of the few who don’t quite fit, thanks to a port wine stain birthmark on my right cheek—a series of vivid fuchsia patches that snake from the outer corner of my right eye across my cheek and into my hairline, covering most of the right side of my face. Years of laser surgery have faded the patches from deep purple to pink, and ordinarily I cover them with makeup so that in everyday life I can shrug off my difference without too much difficulty. But recently, something’s shifted. As our visual culture becomes increasingly fixated upon a narrow ideal of airbrushed perfection, I’ve been reconsidering what it means to be ‘different’. In attempting to answer that question, I’ve spent the last six months talking to women who don’t quite ‘fit’, either.

Advertisement

My first meeting is with Tulsi. Small and sharp-eyed, she is friendly but intimidating and exudes a steely confidence. We’re sitting in a crowded café, and the conversation naturally turns to starers, about whom she is defiant. “I think, now, I’d rather give them something to stare at. If you’re going to look, look properly. I try to make them feel as uncomfortable as they make me.” When Tulsi was just ten years old, she survived a plane crash in which she lost both parents and her brother. Waking up in hospital, her eyes bandaged and her mind dulled by sedation, she says she found the accident hard to comprehend. ‘I can hear voices around me,’ she describes waking up in hospital, slipping into the present tense. “my cousins speaking, my family speaking, and the voices are very close. I’m wondering why my parents aren’t here and they’re trying to explain but it’s not getting through.” For two months, while she underwent intensive treatment for the severe burns that covered her face and body, Tulsi remained unaware of the extent to which her appearance had been altered. She can’t remember if it was she or one of the nurses who first suggested looking in a mirror. “At that point, I didn’t know what burns looked like’, she explains.”So, I was inquisitive more than anything. When the nurse held a mirror up and I saw the face looking back, I asked which of them had drawn it on because it wasn’t me.” In his book, Changing Faces: The Challenge of Facial Disfigurement (1990), James Partridge highlights this moment as definitive in the psychological recovery of a patient with a disfiguring injury. In a sense, it’s actually a repetition of Lacan’s Mirror Phase, the moment an infant first becomes aware of themselves as an ‘I’, which occurs somewhere around the age of 6 to months A unique identity begins to construct itself from this moment on, combining one’s own—often rather delusional—sense of self with the reactions of other people. Partridge, who sustained severe facial scarring when he was 18, argues that after an incident resulting in disfigurement this process must be repeated, fracturing the self-image that existed before. As the port wine stain on my cheek is a birthmark, I have never undergone this kind of re-identification. A few weeks later, I am introduced to Amanda, who was born with a double cleft lip and cleft palate, clubbed feet, missing fingers and no tear duct in her left eye. When I ask her whether there’s a distinction to be made between those who are born with differences and those who sustain them later, she is thoughtful: “if you’re getting bullied for it from the start, that’s how you define yourself. Being born the way I have been makes it a strong part of my identity. It’s not like I have pictures of myself from before to gaze at. This is me.” Amanda has had 39 operations at last count, 25 of which took place before the age of five. If you have always lived with visible difference, in a strange, destructive way you’re encouraged to wait for that moment of psychological Throughout these conversations, the importance of institutions—medical, educational and governmental—becomes increasingly apparent. From the moment a child is born with a visible difference, or an individual is brought in with appearance-altering injuries, they enter into a new kind of relationship with public services. The first, and most enduring of these relationships is with the hospital. Tulsi remembers her initial period of treatment and recuperation as an oasis of calm before her reintroduction to the outside world. “In hospital, I always felt safe because no one treated me differently,” she explains. “On a burns unit they’re accustomed to seeing those kinds of injuries and the doctors and nurses were always incredibly kind to me.

of them had drawn it on because it wasn’t me.

Amanda’s experience was quite the reverse. “I have really horrible memories of hospital. It was the 80s, when children weren’t really listened to in that environment and my first surgeon was ex-army so he didn’t call me by name, just “the cleft girl”. I became rather phobic of surgery.” Later on, when Amanda was picking up cleaning jobs to fund her Masters degree, she found that the industrial cleaning products evoked the smell of hospital operating theatres, making her feel violently sick. Even now, lying with her back flat on the floor recalls the sensation of being wheeled into surgery on a gurney. I meet Natalie—an assistant at a prominent telecommunications company—during her lunch break in a coffee shop in the financial district. Diagnosed with vitiligo when she was just two years old, she describes similar rounds of treatment. It began when her parents noticed a small mark, bright white, almost albino, on her hand, which stood out starkly against her caramel skin. ‘In the 80s it was quite difficult to diagnose someone with vitiligo because people didn’t necessarily know what it was,’ Natalie explains. But after 18 months, 75 per cent of her legs, arms and face were also affected. ‘From that point on I was in and out of hospital—it felt like it was every week. Tring different creams, different patient trials.’ Natalie retreated into herself. ‘I didn’t’ want to answer questions about it, see it or look at it,’ she says sadly. ’I wore two pairs of thick black opaque tights because I hated the idea of anyone realizing that there was something different about me.’ Amanda’s father, whom she describes after a pause as ‘often horrible’, developed a fixation with her surgeries, projecting unrealistic expectations onto the results and telling her that once she completed them all she would look like a

model. Although they never discussed Amanda’s condition as a family, her father documented everything religiously, photographing her before, during and after every surgery, despite her protestations, and typing out every minute detail. ‘He used to rush in and say, “I’ve read in the Daily Mail that they’re growing fingers!” I remember telling him I didn’t want anyone to grow fingers for me.’ When I suggest that in some way, he saw her as an unfinished body, Amanda nods gravely, ‘Definitely. At some point in my twenties, he actually said to me, “You never got to the point I hoped you would, physically,” I supposed he finally gave up on me turning into a model.’ The prevailing assumption, in both medical and social treatment of difference is that we all want to be ‘normal’. For Tulsi, Amanda, Natalie and myself, treatment began well before the age of sexual consent, before the drinking age, and before any of us could vote. I make these comparisons only to highlight the unique way in which we regard ‘correction’ as the default response to difference. In the cases of Amanda and Tulsi, many of the operations that they underwent in their early years were for purely medical reasons and intended to reduce discomfort, as opposed to achieving any kind of aesthetic improvement. Still, the psychological effect of being treated as a work in progress is a pernicious one. Natalie recalls her mother in the kitchen, mixing up different combinations of creams, storing them in the fridge overnight and then slapping them onto her skin the next morning, hoping for a miraculous recovery. ‘When I think back now,’ she says, ‘I would never fault her for doing that because she was following the doctors’ advice. But she was doing it to make me look like everyone else and I don’t think we need to do that anymore.’ Tulsi describes attending a workshop to learn how to cover up scarring and visible injuries with the medical makeup skin Camouflage. She told the expert that she wanted to conceal the pigmentation and uneven textures on her arm, the result of several necessary skin grafts shortly after her accident. Once it was covered, ‘I suddenly started to have a panic attack because I couldn’t see my arm; its textures and colors.’ The expert removed it immediately, but on the car journey home Tulsi was still wiping at it, trying to get it all off. ‘I didn’t expert to feel that,’ she says slowly, ‘I thought I would be happy.’ Tulsi’s surprise at preferring herself uncovered seems to identify another prevailing assumption within our culture—that beauty correlates to happiness. Achieve the former and the latter will follow, no soul-searching required.

Natalie sees things in a rosier light. Having, as a child, been struck by the lack of faces that looked like hers, she finds the recent upswing in positive representation of models of colour and with disabilities cheering. Winnie Harlow, a model with vitiligo, has become one of the most recognisable faces in the industry and takes pains to be seen with and without makeup. ‘I think it’s a lot easier to have a skin condition or disfigurement today,’ asserts Natalie, ‘and in 15 to 20 years time it’ll be even easier. I think I was born in the last generation where it wasn’t cool to be different. Now, it’s cool.’ One commonality that does emerge from these polarised visions of the future is the importance of the narrative we construct as a society. To deliberately misquote Orwell: whoever controls the present controls the future and, as members of a (nominally) democratic society, the agency lies with us. It seems that a simple reframing of the narrative surrounding difference could have a profound effect. When she was about 15, Amanda spent some time volunteering with the Brownies, who she saw were fascinated by her hands. Instead of scolding the children for looking, or concealing them in her pockets, she made up a story in which her hands were a forest filled with rare trees and shrubs, teeming with enchanted animals. The children were transfixed. ‘They were like, “Wow, you’re magical,’” she laughs. ‘So I said, “Yeah, your hands are boring!’” And just like that, for a moment, the paradigm was reversed.