The Discovery of a Lost Masterpiece: An African Boy at the Swedish Court in the Eighteenth Century

By Dr Annemarie Jordan Gschwend

‘Only few tell their story of their life truthfully. This is because of pride, selfishness, fear, sometime shyness, the protection of friends. These five reasons often hinder truth that should be told. But the one who writes these lines, shall not falter, on the road to truth, and [nor shall I make] the reader a fool. The colour of the one who writes is not the same as on what he writes on, but nevertheless, the same as the colour of the lines’.

- Badin (née Couschi), Personal diary, c. 1802-18072

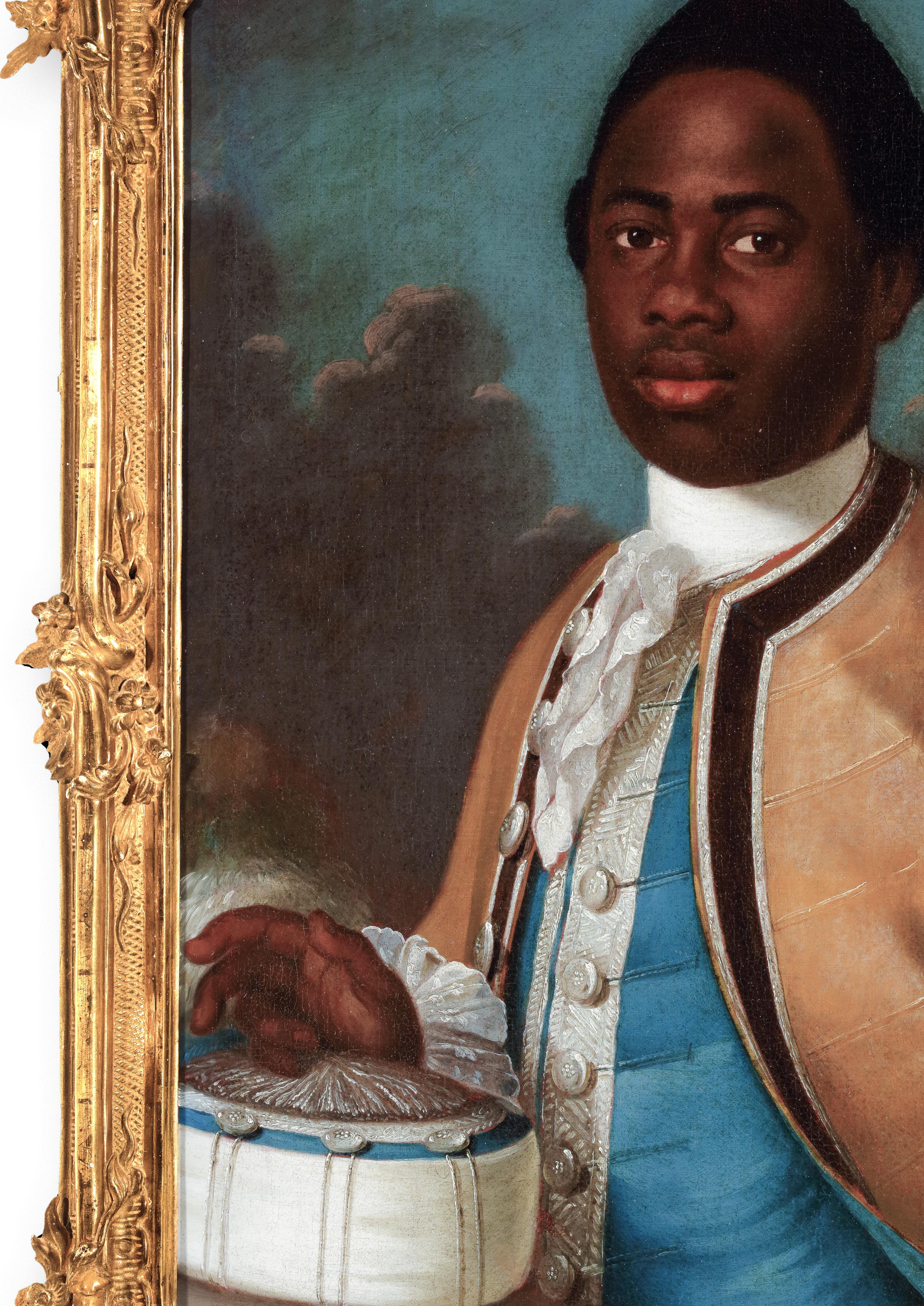

This recently discovered and hitherto unknown portrait of a young black African man wearing the blue and yellow attire of the Swedish court has been identified as the enslaved boy brought to Denmark and Sweden from the Danish colony and island of St. Croix in the Caribbean (Fig. 1).3

According to Lars Wickström’s in-depth study, Badin was born in 1750 into slavery with the surname of Couschi, after his maternal grandmother’s brother.4 His father was named Andris, his mother Narzi, his brother Coffi, and the entire family belonged to the Danish Governor of St. Croix, Christian Lebrecht von Pröck (1718-1780), who returned to Europe in 1758 with the eight-year-old Couschi. Pröck subsequently passed the child to a Dane, Gustaf de Brunck, who, in turn, presented him to the Swedish Royal Court in 1760. Couschi is considered the most famous black African or Afro-Caribbean in Swedish history.5

As the boy transitioned into his new home, he was given the French nickname ‘Badin’6 by Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia (1720-1782), the spouse of King Adolf Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp (r. 1751-1771), to whom he was gifted.7 The queen bestowed this sobriquet because of Badin’s playful character and childish mischievousness. It would ultimately become his official surname. In the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment (in Sweden known as the Age of Liberty), Queen Louisa manumitted and adopted Badin, raising her foster child alongside her royal children who were the same age, albeit Badin was allowed more space and freedom than the royal children. In 1768, he was baptised at age eighteen in the chapel of Queen Louisa’s impressive Baroque residence, Drottningholm, outside Stockholm.8 The extended royal family assisted at this celebration. His foster parents and siblings acted as his godparents, while his given name, Fredrik Adolf Ludvig Gustav Albrecht (c. 1750-1822), reflects the regal names of past and present Swedish kings and princes.

Badin’s positive identification here is based upon two portrayals, one a portrait executed the previous year in 1775 by Queen Louisa’s court painter (hovkonterfejare), the renowned Rococo pastelist Gustav Lundberg (1695-1786). This earlier work is discussed at length below. Drawings and caricatures made of the young Badin while growing up at court sketched by artists who frequented the Stockholm

Royal Castle and Drottningholm Palace have survived, two of which are also discussed below. It is, however, a later realistic drawing by the Swedish engraver and miniaturist Anton Ulrik Berndes (1757-1844), Gustav Lundberg’s former pupil, that helped secure the identification (Fig. 2).9 Berndes signed his sketch with his initials and dated it 15 July 1793, the day Badin sat for him. In this intimate portrayal, we are confronted with a mature, older, welldressed Badin, now a celebrated citizen of Stockholm, who became a member of the Freemasons and was respected as an accomplished intellectual.10

The present portrait, is an extended bust-length portrait of Badin, which portrays him at age twenty-six, discreetly coiffed and dressed in attire. His kid leather cap with silver embroidery and silver tassel is placed on a ledge to

Credit: Alamy Ltd, UK

6

Fig. 2

Anton Ulrik Berndes, Portrait Drawing of Badin as a Freemason, detail with Badin’s head, Stockholm, 15 July 1793.

his right, upon which he casually rests his right hand. The left arm, cut at the wrist cuff, is placed upon his hip. The elegant yellow and blue costume with large silver buttons, white collar, and white lace chemise echo contemporary uniforms worn by the Swedish militia. A rare work written by the officer Carl Gustav Roos, Recueil des Uniformes de l’Armée Swedoise (probably Stockholm, 1783), illustrates the military attire of generals, infantry, and officers during Gustav III’s reign. This hand-coloured folio in Roos’ book of an aide-de-camp compares with Badin’s attire; instead of the dominant blue and yellow, the preferred martial colours, the black African wears a yellow silk or velvet jacket with black trim over a blue vest edged with silver (Fig. 3). Badin’s attire heightens his elevated status and position at the Swedish court, see also for instance the formal costumes preserved at the Swedish Royal Livruskammaren, object no. 31869, 19227 & 31870. (Fig. 17 & 18) He is not portrayed as just a ‘Moorish’ chamber servant or ‘black page’ (kammermohr).11 We are confronted with a singular portrayal in which the sitter is shown with confidence and self-assurance. Badin gazes at the viewer with pride, a black African who had attained upward mobility in his social context and milieu.

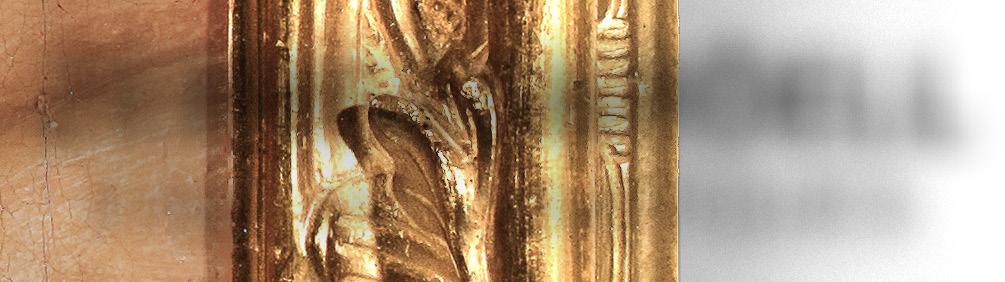

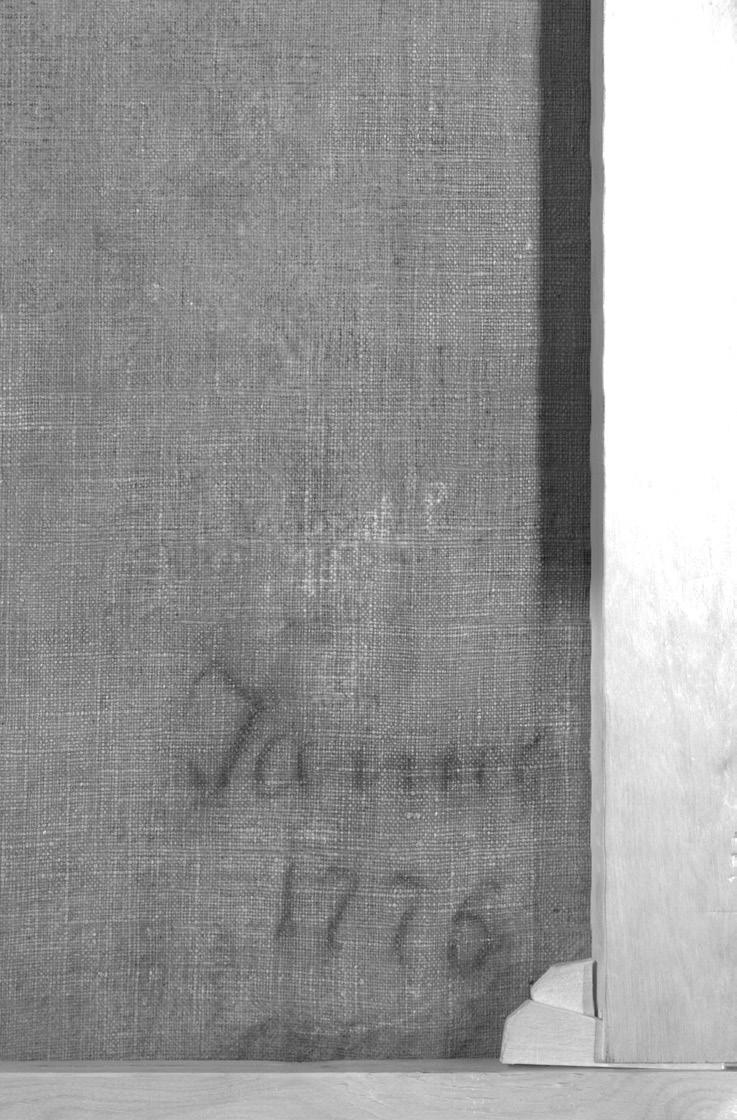

Queen Louisa commissioned Badin’s portrait to mark a specific event and a significant turning point in his life when she appointed her foster son her secretary in 1776; this year, inscribed on the lower right reverse of the canvas (Fig. 4).12 After this promotion, Badin became the queen’s closest confidante and companion, upon whom she would implicitly rely and trust more than her children.

Portraits, particularly this one of her favourite Badin, mattered to Louisa. The queen’s appreciation of portraiture

is well documented, developed since her youth at the Prussian court in Berlin, where the Frenchman Antoine Pesne (1683-1757) served as the leading court portraitist to her father, the King of Prussia, Frederick Wilhelm I (16881740) and her elder brother Frederick II (1712-1786; better known as Frederick the Great).13 Louisa Ulrika was born in Berlin in 1720, the tenth child of Friedrich Wilhelm I and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Hannover. Raised at the Prussian court, the young princess received a solid education from French Huguenot expatriates. She was fluent in French and knowledgeable in music, theatre, literature, and the sciences, educated as an enlightened princess, having mixed at the Berlin court with leading international artists, Italian opera singers, and celebrated French philosophers, such as Voltaire, a protégé of her brother Frederick II, and with whom she corresponded.14

As queen, Louisa imaged herself at the Swedish court and amongst Stockholm’s aristocratic and intellectual society as an enlightened ruler and dynamic patron of the arts, science, and letters. She established the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters (Kongl. Swenska Witterhets Academien) in 1753, informally known as the ‘Queen’s Academy’.15 She promoted Swedish painters and encouraged the development of theatre by reconstructing a theatre at Drottningholm Palace, where plays were performed in French. Above all, she was also a passionate, erudite art collector. Louisa Ulrika avidly collected portraits of rulers and learned scientists and commissioned images of her court ladies for a “Gallery of Beauties”, curating the hanging of these diverse portrayals in specific rooms and galleries at Drottningholm. In one new room, the Green Room, added during her reign, she displayed her Prussian royal family and siblings to remind visitors of her illustrious

7

Fig. 3

Carl Gustav Roos, Recueil des Uniformes de l’Armée Swedoise (probably Stockholm, 1783), 1783-1789, fol. 53. Credit: Public Domain

Fig. 4 Reverse of Badin’s portrait, Credit: Art & Research Photography, Amsterdam

origins and pedigree.16 Louisa encouraged painters to come and study her Drottningholm artworks and paintings. Therefore, her input in this explicitly commissioned portrait of Badin as her new royal secretary cannot be underestimated.

Queen Louisa likely ordered a preliminary pastel study of Badin by her favourite painter, Gustav Lundberg, which must be considered lost. Because of the delicate nature and surfaces of pastels, sensitive to light, moisture, and touch, and which had to be protected by glass, copies in oil were invariably made from the onset. She immediately had this lost pastel replicated in oil, attributed here to Jakob Björk, a Swedish portrait painter and copyist active for twenty-four years in Lundberg’s workshop from 1750 to 1774. Björk worked primarily executing oil copies of Lundberg’s pastels for numerous royal and aristocratic clients, among them Queen Louisa and her favourite minister, Count Carl Gustav Tessin (1695-1770), and he continued to do so after leaving Lundberg’s atelier.17 As Laine and Brown stressed, replicas of Lundberg’s portraits, both in oil and pastel, circulated in large numbers outside his studio.18

As a copyist, Björk’s style relied upon Lundberg’s originals, in which sitters are positioned, bust-length, close to the foreground plane, with neutral brownish-green backgrounds. The high rank and status of the sitters are highlighted by their poses, elegant costumes, accessories,

and jewels. In his oil copies, Björk faithfully reproduced Lundberg’s compositions, as evidenced in the painting of Count Anders Rudolf du Rietz (1720-1792), recently seen on the art market (Fig. 5b).19 Dressed in a blue and yellow Swedish uniform, underneath which his half-armour is visible, Du Rietz prominently wears the Swedish Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword on his left breast; his portrayal reflects the pride of a career officer. When it is compared with the pastel of the Count Claes Julius Ekeblad (1742-1808) by Lundberg (Fig. 5), it becomes clear that Björk is the painter of the oil painting depicting Badin.

Badin’s portrayal imparts a similar psychological characterisation, dignity, and self-esteem. Queen Louisa decided which clothes Badin should wear here, as she did in Lundberg’s 1775 pastel of Badin (see below), probably responsible for the cut and design of both costumes, ever conscious as queen of the visual impact of clothes and dress accessories.20 She equally chose the background setting with Lundberg, which Björk has repeated: a garden with billowy trees that frames Badin, representing her park at Drottningholm palace, where her foster son grew up and lived with the royal family. Diplomats and eyewitnesses at the Swedish court recount in their diaries and travelogues that Badin was short and somewhat stout 21 Badin is fashioned here as the elegant and handsome courtier he had become while growing up in Queen Louisa’s intimate surroundings.22

8

Fig. 5b

Jakob Björk (after Gustav Lundberg), Portrait of Count and Lieutenant-General Anders Rudolf du Rietz, c. 1775-1777, oil on canvas, 67 x 52 cm. Present whereabouts unknown. Credit: Public Domain

Fig. 5

Gustav Lundberg, Portrait of Count Claes Julius Ekeblad, Major General, Governor, and Lord Chamberlain, after 1775, pastel on paper. Nordic Museum, Stockholm (inv. no. NM.0239302)

White Knight, Black Bishop, Checkmate: Badin, Master of Chess

One year prior, the Swedish queen commissioned Badin’s most memorable portrait, which hangs almost 250 years later, in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Fig. 6).23 Louisa arranged for Gustav Lundberg to paint it in a single day on 4 July 1775, an artistic contest, which the pastelist met with aplomb, expertise, and refined technique. The precise details of the queen’s challenge and why her court painter had to execute this pastel quickly are unknown.

Badin is dressed in a fantastic costume with pigeon blue ribbon trimmings, also draped around his neck, thickly encrusted with rock crystal stones, as is the edge of his hat. Opulent white ostrich feathers enhance his attire and adorn his hat; some dyed red and blue. A gold leather case (quiver) filled with arrows is visible above his left shoulder. Queen Louisa deliberately chose Badin’s clothes. This scene mimics a theatrical production packed with multilayered significance, underscored by Badin’s tongue-in-cheek look, pose, and the red and white chess board on a table before him.24 As with the slightly later 1776 portrait under scrutiny here, Lundberg has positioned Badin very close a neutral greyish-green background. Louisa earmarked Roslin’s portrait for her collection at Drottningholm.

to the foreground. The brownish-green background, typical of Lundberg’s style, is heightened with light blue in the middle, spotlighting Badin. this challenging game, a metaphor for the well-educated, courtly gentleman Badin had become by 1775.

That same year, the renowned Swedish painter Alexandre Roslin (1718-1793), who had lived abroad in Bayreuth, Parma, and Paris for his entire life, visited Stockholm after being elected a member of the Swedish Academy of the Arts. During his sojourn in 1774-1775, he took many portraits of the Swedish royal family, including this portrayal of Queen Louisa as the elderly Dowager Queen, which she must have ordered simultaneously with Lundberg’s pastel of Badin, her portrayal almost identical in size (Fig. 7).27 In keeping with Gustav Lundberg’s style of portraiture, Roslin depicts Louisa in lavish attire, richly adorned with pearls and diamonds. As in Lundberg’s pastels, she is seen against

Badin’s portrait, with its ornate neo-classical Gustavian frame, received a place of honour in the queen’s apartment elsewhere at Fredrikshov,28 her winter palace in Stockholm, displayed in her blue study or cabinet d’étude, located in a wing she added there in 1772-1774 now destroyed, designed by her architect, Carl Frederik Adelcrantz.29 She carefully selected the furnishings in this small room, contrasting Asian and European objets d’art. The curtains and the upholstery of the gilded seats were blue taffeta with gold braiding. The Swedish Rococo-style desk with a bookshelf or etagère by the master cabinetmaker Nils Dahlin (active in Stockholm, 1761-1787), after French models, were inlaid with imported Chinoiserie black and gold lacquer panels, outfitted with burnished gilt Ormulu

9

Fig. 6

Gustav Lundberg, Portrait of Badin playing chess, 1775, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, pastel on paper, 74 x 57 cm, inv. no. NMGrh 1455.

Credit: Public Domain

fittings. Stamped with the queen’s initials and dated 1771, this site-specific furniture has survived.30 A bronze French clock with the Allegory of Learning (a woman reading a book) crowned Dahlin’s bookshelf. Other items included export wares: a Japanese lacquer cabinet, four grey and gold potpourri jars, and a fire screen made with painted Indian paper. On the walls, Queen Louisa elected to juxtapose her ‘exotic’ black son - dressed in the matching blue of her study - with a white porcelain bust of the Russian Empress, Catherine the Great (1729-1796), a female ruler she admired. It was an intentional play with black and white. As the queen’s appointed secretary after 1776, Badin was quite familiar with this room and its contents, having unique access to this space and the key to her private files.

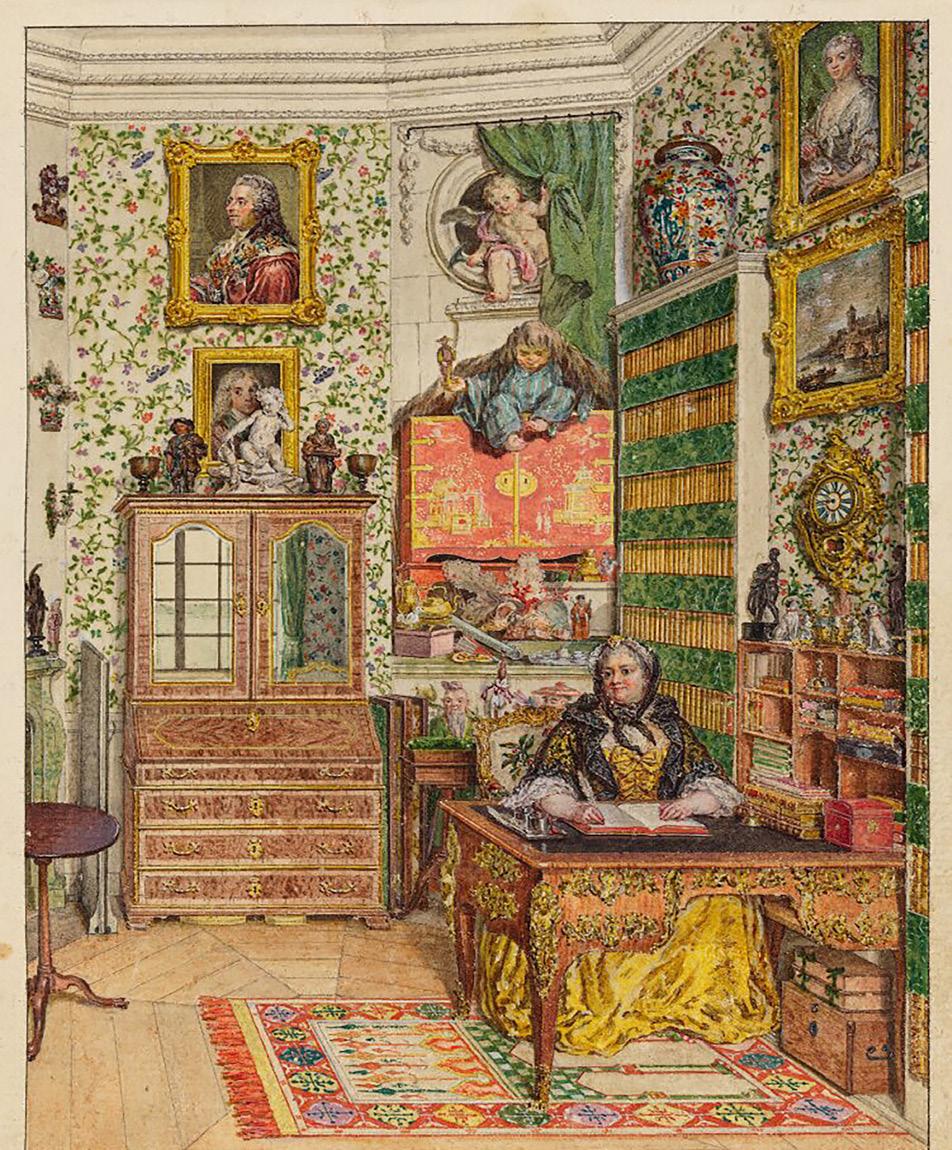

To better visualise Queen Louisa’s blue étude, illustrated here is a small watercolour depicting Countess Louisa Ulrika (Ulla) Sparre in a similar cabinet at her country estate in Åkerö (Fig. 8).31 The wife of Count Carl Gustav Tessin, Queen Louisa’s minster and a passionate art collector,32 Countess Sparre, in her collecting craze, densely furnished her study, much like the blue étude at Fredrikshov. This tiny space, with the countess portrayed at her desk, is crammed with collectables where Asia and Europe intersect. This study was her Kunstkammer (an art chamber) in which naturalia, such as coral, were displayed alongside exotica, such as Asian export wares. Books, paintings, small-scale bronze sculptures, a gilt bronze Rococo clock, a Chinese Imari baluster jar with a cover (Kangxi period, 1622-1722), and a Chinese red and gold lacquer cabinet compete for attention. Above Countess Louisa’s desk is a portrait of an unidentified female painter holding a painter’s palette, possibly by the Venetian Rococo pastelist Rosalba Carriera

(1673-1757).33 On the upper wall in the background is Gustav Lundberg’s pastel portrait of her husband, Count Tessin, which can be seen in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm today.34

African Precedents

In their exhaustive monograph on Gustav Lundberg’s career as painter and pastelist, Laine and Brown looked closely at Queen Louisa’s commissioned pastel of Badin, detailing the artistic sources, established iconographies and stereotypes Lundberg incorporated here.35 The ostrich feathers and gold quiver with arrows echo earlier depictions of socalled ‘moors’, or better, Africans, prevalent in manuscript illuminations, artworks, prints and the decorative arts since the late Middle Ages. This Allegory of Africa, one of the world’s four continents, executed in 1709 by Francesco Trevisani (1656-1746) or his workshop in Rome, encapsulates these wide-spread pictorial models (Fig. 9).36 The African continent is symbolised by an elephant mounted by a half-clad, bejewelled black lady with a parasol, personifying Africa.

In keeping with his eccentric dress and theatrical presentation, Badin’s hair is unruly and uncoiffed, his face unshaven, his black coat reflecting the colour of his black skin underneath. The deliberate reference to ‘African’ elements underscores Badin is not dressed in conventional court attire but wears a stage costume, perhaps one worn during his brief period as an actor and ballet dancer in plays and masquerades held at the French Theatre in Bollhuset in Stockholm between 1769-1771.37 Badin also performed in the Royal Palace, playing the lead as an African ‘savage’ in Pierre de Marivaux’s Arlequin Sauvage A rare watercolour of an African ballet dancer by Louis-

10

Fig. 7

Alexandre Roslin, Portrait of the Dowager Queen Louisa Ulrika, 1775, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, oil on canvas, 74 x 58 cm, inv. no. NMDrh 35. Signed and dated: 1775. Credit: Public Domain

Fig. 8

Olaf Fridsberg, Portraits of Illustrious Men, with Short Biographies of Their Lives, written by Mme la Comtesse de Tessin, 1760s, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, watercolour on paper, 23 x 19 x 5.5 cm, inv. no. NMH 145/1960. Credit: Public Domain

René Boquet (1717-1814), a costume designer for the Paris Opera, may well reflect the costume worn by Badin in 1770 (Fig. 10).38 During this theatrical phase of his life, Badin collaborated with the Swedish court poet, entertainer and songwriter Carl Michael Bellman (1740-1795), with whom Badin composed songs and poems, even appearing in Bellman’s divertissement, Carneval de Venise, staged for the Dowager Queen Louisa, by order of her son King Gustav III in 1776. The production, which recreated Venice with St. Mark’s Square, and the Rialto bridge, took place in the king’s cabinet (Cabinet du Roi) with Badin acting as the masked ‘blackamoor’ in Venetian carnival costume.39

Since her childhood at the Prussian court, Queen Louisa was interested in the Africans she had encountered there and, subsequently, at her brother Frederick the Great’s court, where black men were engaged as musicians and soldiers. The life of one man, especially, fascinated her. Anton Wilhelm Amo (c. 1703-c. 1759) from Ghana, protected by Louisa’s elder sister, Philippine Charlotte of Prussia (1716-1801), Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, was encouraged to study, receiving his doctorate in Wittenberg in 1734. Amo lectured at the Halle and Wittenberg universities and wrote a now-lost treatise on the rights of black Africans in Europe. Much like Badin’s story, another eighteenth-century narrative which fascinated European courts was the remarkable career of the African courtier and royal tutor Angelo Soliman (Mmadi Make, c. 1722-1796) at the Habsburg imperial court in Vienna.

Brought as a slave child to Europe, he achieved prominence in Viennese elite society, highly respected as a cultured man in intellectual circles, joining the Freemason Lodge, ‘True Concord’ (Zur Wahren Eintracht) in 1783, as Badin had in Stockholm in 1773.40 During her reign, Queen Louisa cultivated relations with men of letters, scientists and

philosophers who devoted themselves to studying Africans, such as Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1759), who once resided at Frederick II’s court in Berlin.

The arrival of Mapondé, an enslaved five-year-old African boy with albinism from Angola in Paris in January 1743, created a sensation because of his genetic condition and rare skin colour. Maupertuis, who closely studied Mapondé, was so fascinated by the enigma that a ‘white’ child could be born of black parents he was inspired to write and publish a treatise, La Dissertation Physique à l’occasion du Nègre Blanc (Leiden, 1744).41 News reached the Swedish queen’s minister, Count Carl Gustaf Tessin, the former ambassador to France, who managed to obtain this outstanding, insightful portrait by Jean-Baptiste Perronneau (c. 1715-1783), taken the year Mapondé arrived, which today is in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Fig. 11)42 Tessin gifted this pastel to Queen Louisa, who gave it a place of prominence at her palace in Drottningholm. Perroneau showcases the young Mapondé as a dignified, almost majestic sitter, three-quarters in length, facing to the left. The viewer is nevertheless confronted with a strange ‘curiosity’ - a white-skinned black African boy with expressive blue eyes and white hair dressed in an exotic red silk gown. His ceremonial costume is complimented by his long grey cape and red cap in his right hand, both lined with grey fur, recalling Turkish caftans. Mapondé is explicitly dressed as an oriental Ottoman to reference his ‘otherness’. When commissioning Gustav Lundberg’s pastel of Badin, her ‘wild African boy tamed by court society and its mores’, Queen Louisa looked for inspiration to Perroneau’s earlier, realistic portrayal of Mapondé, which had been in her collection for decades. Mapondé’s portrait and story are images and narratives Badin would have seen and heard at Drottningholm Palace.

11

Fig. 9

Francesco Trevisani and studio, Allegory of Africa, 1709, Amsterdam, Zebregs and Röell Fine Arts & Antiques, oil on canvas, 74.5 x 61 cm.

Fig. 10

Louis-René Boquet, Costume Design for an African Ballet Character, Amsterdam, Zebregs&Röell Fine Arts & Antiques, pen, ink and watercolour on paper, 25.2 x 18.7 cm.

Before 1775: Educating the Queen’s Son

Much ink has been spilt about Badin’s representation in Lundberg’s pastel as the ‘exotic other’, the civilised boy, playing chess in the context of the white Swedish court. Lundberg’s portrayal encapsulates Badin’s biography and life up to 1775, reflecting the close ties and friendship Queen Louisa cultivated with her foster son, whom she liberally educated, following the edicts of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), who in 1762 published his Émilie (or On Education). Rousseau’s premise was small children should be free of formal education, advocating an upbringing without constraints.

Louisa fashioned herself as an enlightened monarch, and when granting Badin his freedom, she allowed him to be raised as a human scientific experiment in keeping with Rousseau’s precepts. Spirited and ill-behaved, Badin could roam free in all the royal palaces he resided in, never reprimanded nor scolded. He could say what he wished and treat his royal siblings as he liked. He often called his adopted brother, the crown prince and future king, Gustav III, a ‘scoundrel’. Queen Louisa thought him witty and verbal. Contemporaries, visitors, and courtiers alike were appalled at the results of her unconventional parenting methods. The Swedish Chancellor, Count Fredrik Sparre, harshly criticised Badin in handwritten notes dated 1763, having himself suffered from the boy’s rudeness:

“It’s [Badin’s] disposition is, like that of all Morians [Swedish for ‘moor’ or black African], very quick, which can be so much less strange that in his upbringing, the rule must be followed to let him do, most of the time, what he wants, at least never let him be nagged with any body language.”

Sparre found Badin’s manners and speech blunt and gross, disapproving he was allowed to run in and out of rooms, climb on the royal thrones, and hang around during meals between the king’s and queen’s chairs. On many occasions, Badin would race around the table, take food from the plates and cause guests to laugh.43 Once, he popped out of a large baked pie. The queen’s lack of discipline transformed the young Badin into a court jester. A littleknown pen and ink drawing of Badin standing on a podium with a jester’s cap, playing the violin, by the queen’s court architect, Jean-Eric Rehn (1717-1793), gives us a glimpse of his early life at court as a form of entertainment. (Fig. 12)44 Another sketch by Rehn gives an even better insight into life at Drottningholm Palace in the queen’s quarters, capturing a moment in time at Queen Louisa’s court (Fig. 13).45 The French sculptor Pierre Hubert l’Archevêque (1721-1778) shapes her portrait bust in clay to the far right.46 Behind, to the left, by the window, she stands next to her official reader, the Swiss Jean François Beylon (1724-1779), whoreads her a text, without doubt in French while a grinning, mischievous Badin peeks from behind

Credit: Public Domain

12

Fig. 11

Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, Portrait of the Albino Child Mapondé, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 1743, pastel on paper, 75 x 56 cm, inv. no. NMB 1674. Credit: Public Domain

Fig. 12

Jean Eric Rehn, Drawing of the young Badin dressed as a jester playing the violin, c. 1760, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, pen and ink on paper, 19.6 x 15 cm, inv. no. NMH 444/1995. Inscribed on the reverse: “Badin négre de la reine Louise Ulrique de Suede, dessiné 1757”.

A Black Swedish Courtier in Prussia

Three years after his baptism, Badin travelled to Prussia, experiencing the country where his patroness grew up. In 1771, after her husband, King Adolf Frederick, died, Queen Louisa was invited by her elder brother, Frederick II, to spend time at his court.53 She arrived on 3 December with an entourage of 82 people, including Badin.54 This trip abroad marked a turning point for him as an educated black courtier. He resided in Berlin for almost a year, becoming the ‘darling’ (joujou) of Prussian royal society because of his eloquence and wit; his presence was coveted everywhere, not just because of his colour. He was invited daily to visit Frederick’s queen, Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern (1715-1797) and the homes of other princesses and court ladies, as Queen Louisa duly reported to her son, Gustav III, in Stockholm.

“As in Stockholm, Badin is everyone’s plaything [joujou] here. The Queen and the Princesses order him to visit them, and he is invited every day, evening, and dinner in town.”55

the sculptor’s legs. Rehn has chosen to caricature Badin as short, rotund with pronounced, exaggerated African features.47

The Rousseau experiment inevitably failed as Badin grew older. Queen Louisa realised her undisciplined young teenager needed education. In preparation for his baptism, she appointed Nathanaël Thenstedt (1731-1808), a Swedish preacher, to instruct him in Christian doctrine, reading and writing, and other subjects.48 Thenstedt tutored Badin from 1763 to 1768; his baptism was celebrated in the chapel of Drottningholm Palace on 11 December 1768. Badin became a gifted polyglot, having mastered Latin, German, French, and Swedish, fluent in the latter two, as his diary confirms. Badin was wellread and appreciated books and, as an adult, amassed a library which counted eight hundred volumes, sold at auction after he died in 1822.49 His high status at Queen Louisa’s court granted him multiple social advantages, as in the 1760s when he met at royal soirées and dinners the Swedish philosopher and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), a harsh critic of slavery and the first Swede to condemn slavery.50 As his diary reveals, Badin’s discourses with Swedenborg transformed his views regarding faith and spirituality.51 After his baptism, Badin refashioned himself from a court jester to a pious, devoted Christian, becoming Queen Louisa’s most trusted secretary, with her 1776 portrait by Jakob Björk marking this momentous transition in Badin’s life.52

Badin and Queen Louisa partook in a full social agenda of concerts, entertainments, operas, dinners, and sightseeing, including a special tour of Frederick II’s Rococo palace of San Souci in Potsdam, where they visited the terraced gardens, park, and the superb art collections of French paintings, among them, works by Jean-Baptiste Pater and Antoine Watteau.56 Badin’s exposure to the arts, culture, music, theatre, and intellectual circles cultivated by Frederick and the Prussian royal family left an indelible mark on him, with Badin wishing to remain in Berlin to study astronomy.57 However, his complex relationship with Queen Louisa influenced his return to Stockholm a year later. After 1771, Badin proved indispensable to the queen because of his loyalty, discretion, and knowledge of the inner workings of the Swedish court, becoming the ears and eyes of the queen and her son, King Gustav III.58 His devotion and loyalty were unconditional, to the extent that he aided in burning Queen Louisa’s papers - upon her directives - after she died.59

More Transitions

Badin’s career at the Swedish court continued to thrive after the loss of his adopted mother. King Gustav III respected his adopted brother’s talents and capabilities, appointing him the assessor of two royal estates in Svartsjö.60 A receipt for the rental of a country house and garden in October 1782 signed by Badin has survived, marking his new career as a royal estate manager and officer with judiciary powers (Fig. 14).61 He remained in Gustav’s service until the king’s assassination in 1792.

Badin took the initiative and oversaw the commission in 1794 of a commemorative silver medal to honour his dead brother executed by Carl Gustav Fehrman (17461798),62 which depicts the bust of the late king on a plinth with a naked, winged old man with an hour clock; the personification of Time, extending his hand towards the dead monarch (Fig. 15).63 Scattered on the ground and on the plinth - the letter G for Gustav inserted in a six-sided star - are masonic symbols, including a compass and a square, referencing the late king’s membership. Afterwards, Badin retired from court life, purchasing two farms in Uppland, where he kept his extensive library, to live the life of a country gentleman.

13

Fig. 13

Jean Eric Rehn, Drawing of the young Badin, Queen Louisa Ulrika, Pierre Hubert l’Archevêque and François Beylon at Drottningholm Palace, c. 1760, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, pen and ink on paper, 36.8 x 26.5 cm, inv. no. NMH 543/1995. Credit: Public Domain

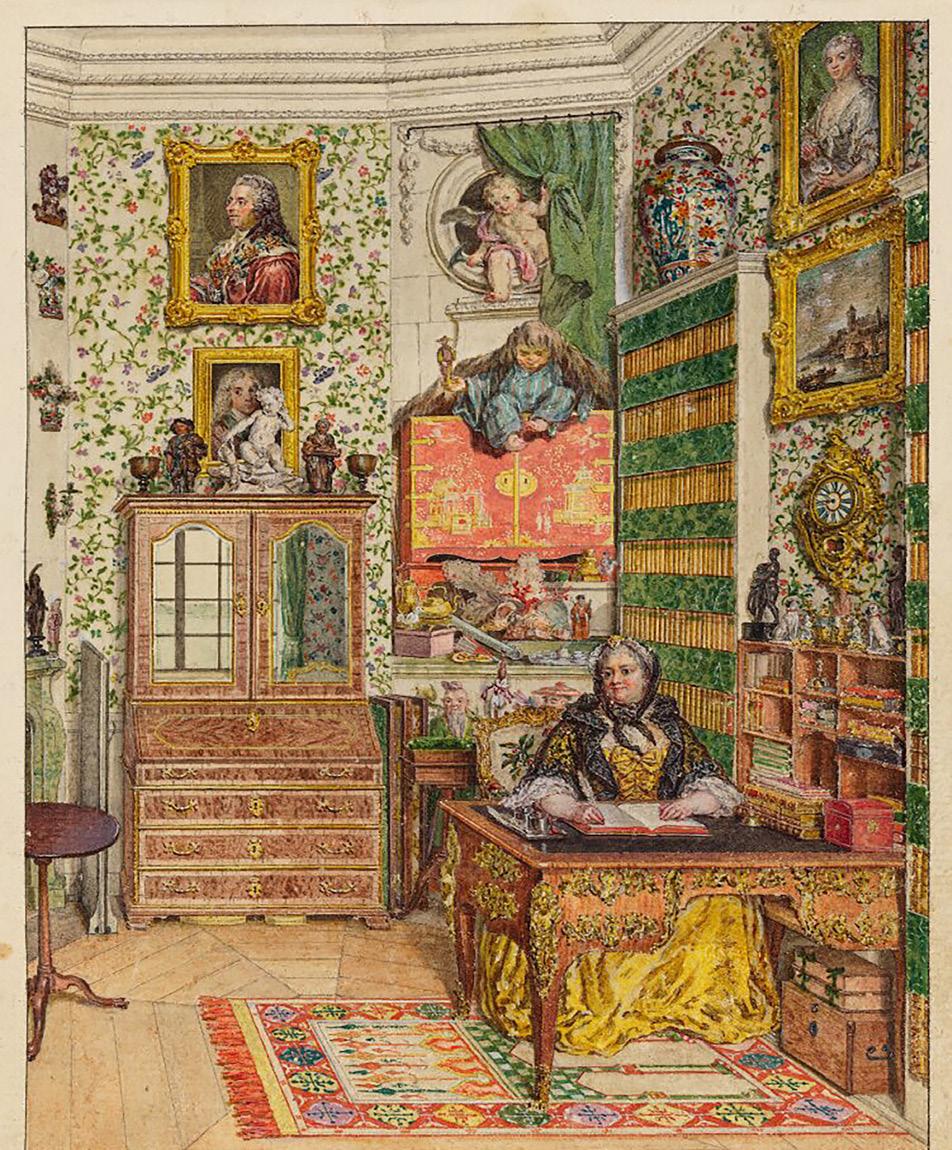

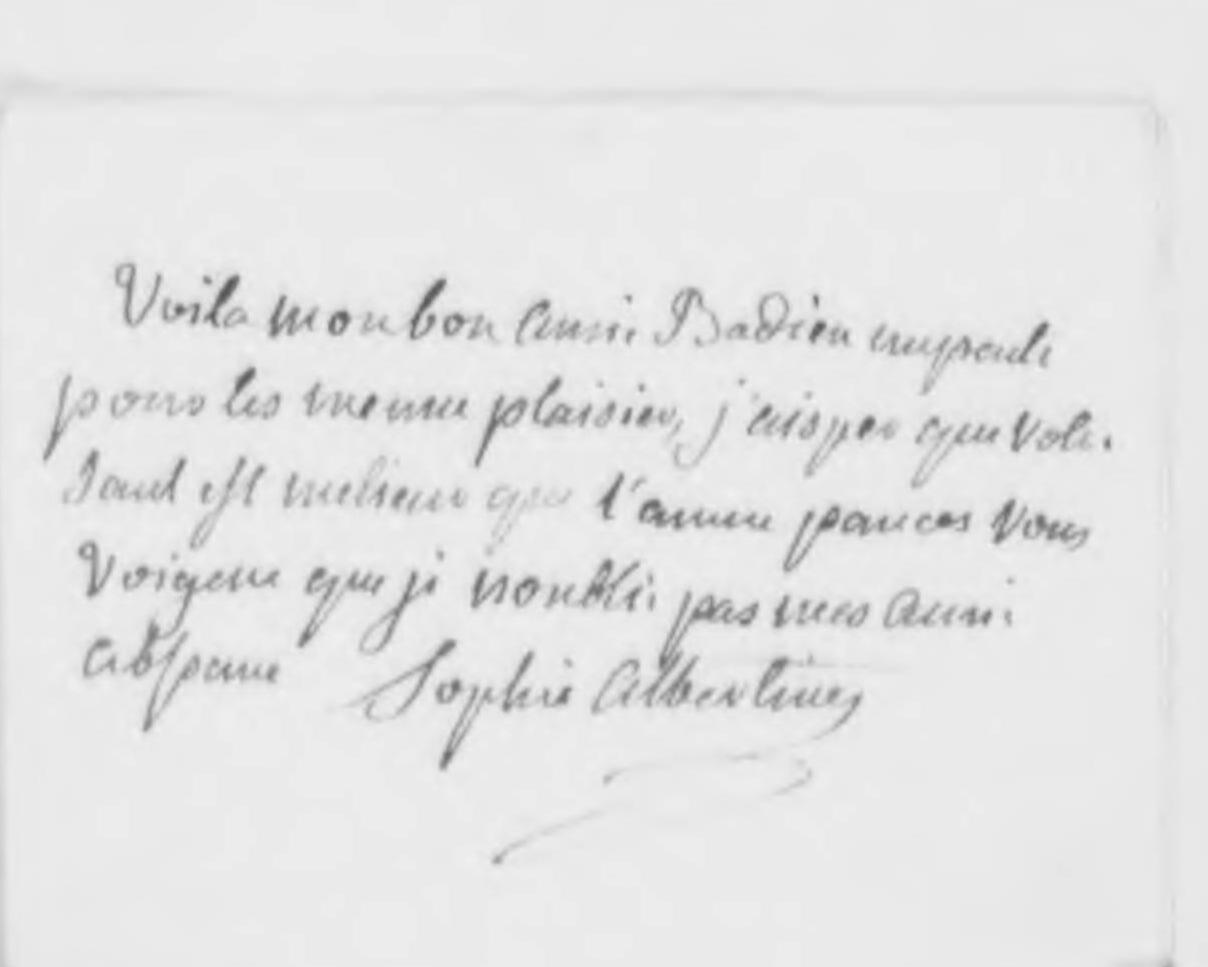

Badin also remained connected to the household of Queen Louisa’s unmarried daughter, Princess Sophia Albertina (17531829), a foster sister he had been particularly close to since his arrival at the Swedish royal court in 1758. This princess watched over Badin’s welfare, and after his first marriage to a white Swedish merchant’s daughter, Elisabeth Svart, in late 1782,64 she granted him a lifetime annuity. A surviving letter confirms her friendship, support and a gift of money (Fig. 16).

‘Here, my good friend Badien [sic; Badin], a gift for your little pleasure; I hope your health is better than last year. You see that I do not forget my absent friends. Sophie Albertine’.65

This princess inherited outstanding artworks and portraits from her mother’s diverse collections after 1782; one was Jakob Björk’s masterful portrayal of Badin as the queen’s royal secretary. Owning this portrait was a personal choice. Sophia’s private residence, Arvfursten Palats in Stockholm, was remodelled by Erik Palmstedt between 1793 and 1794; Louis Masreliez (1748–1810) designed the interior salons in a neoclassical Gustavian style. In the Sällskapsrummet, or the drawing room, Princess Sophia and her courtiers spent hours conversing and embroidering. Most likely, Badin’s 1776 portrait once hung in this representative room. In 1829, the same portrait was recorded in her post-mortem inventory on fol. 110, entry 79 as ‘Portrait de Mr Badin’, appraised for 20 Swedish riksdaler.66 Princess Sophia’s residence is the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs today. Her former Arbetsrummet (study), which initially served as her bedroom and later as her waiting room, contains furnishings dating to her residency still in situ.

Badin’s Legacy

In November 2023, Crown Princess Victoria attended the unveiling of a headstone for Gustav Badin at the Katarina Cemetery on Södermalm in Stockholm, where fellow Freemasons had buried him on March 18, 1822. All traces of Badin’s original grave have since been lost. The National Organisation of Afro-Swedes took the initiative to honour Badin, and they erected this fitting memorial for a former enslaved African who carved out a brilliant career at the Swedish court, refashioning himself as a jester, butler, ballet dancer, actor, erstwhile poet, secretary, and official royal inspector. Badin loved culture, the arts, music and his books. As a Freemason and a person of African descent deeply concerned with his black identity, impacted by the Age of Enlightenment philosophers and intellectuals whose paths he crossed in Sweden and Prussia, Badin believed in social reform, and like others in his court circles and secret societies advocated against racial discrimination in eighteenth-century Sweden.

Jakob Björk’s portrait of Fredrik Adolf Ludvig Gustav Albrecht Badin, née Couschi, is a unique testimony of his life and career at Queen Louisa Ulrika’s court, reflecting his amazing transition from a court entertainer and jester to a trustworthy royal secretary and land assessor. It is a remarkable masterpiece and portrayal of a black Afro-Carribean-Swede to have been rediscovered.

Credit: Public Domain

Credit: Public Domain

15

Fig. 14

Rental contract signed by Badin, Stockholm, 21 October 1782, Uppsala, Uppsala University Library, Erik Wallers Autografsamling, ink on paper, 320 x 200 mm, shelfmark: Waller Ms se-00156. Signed: Adolph Ludwig Badin.

Fig. 15

Garl Gustav Fehrman, Commemorative Medal of King Gustav III commissioned by Badin, 1794, Uppsala, Gustavianum, Uppsala Univeristy Coin Cabinet (Myntkabinett), 1794, silver, diameter: 50.94 mm.

Fig. 16

Note written by Princess Sophia Albertina to Badin with a gift of money, Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Ericsbergsarkivet, Autografsamlingen, Sverige, Sofia Albertina, vol. 282, unfoliated (no date, no location).

I am grateful to Merit Laine, who generously shared archival sources and helped guide me through the holdings of the Riksarkivet in Stockholm. Marie-Louise von Plessen and Franz Pichorner were just as helpful and forthcoming with information. Ragnar Hedlund at the Uppsala Univeristy Coin Cabinet helped clarify queries regarding the 1794 commission of a medal of King Gustav III in his collection. I thank Kate Lowe and Hugo Miguel Crespo for reading earlier drafts of this essay.

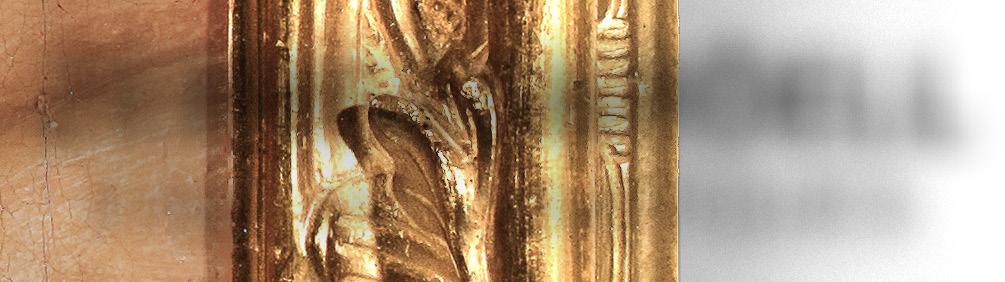

1 Laine and Moberg, 2015, pp. 209-212; Laine and Brown, 2006, pp. 226-233 and p. 245. Consult as well, Serge Roche, Cadres français et étrangers du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle: Allemagne, Angleterre, Espagne, France, Italie, Pays-Bas, Paris, E. Bignou, 1931; Bruno Pons, ‘Les cadres français du XVIII siècle et leurs ornaments’, in: Revue de l’Art, 76, 1987, pp. 41-50

2 Badin’s autograph diary (Dagbook), written in Swedish, is interspersed with commentaries in French. Located in Uppsala, Uppsala University Library, ink on paper, 37 pages, 16 x 10.5 cm, Shelfmark: X 252 a. Acquired in 1916 as a donation given by the French professor Oscar Quensels. Consult online: https://www.alvin-portal.org/alvin/ view.jsf?pid=alvin-record%3A84300&dswid=7423 (accessed 15 December 2023). Cf. Pred, 2004, p. 8, cites a transcribed manuscript of Badin’s life in the archive of the Par Bricole Bacchanalian Society in Stockholm (inv. DIj). More recently, Basir, 2015. Badin wrote entries about spiritual love, poems on the beauty of flowers and friendship.

3 This island was purchased by the Danish West India Company from Louis XV, King of France, for 750,000 livres in 1733. St. Croix (together with St. Thomas) were sold by Denmark to the United States in 1916. Badin is thought to have been born either in West Africa or St. Croix. As an adult, Badin remembered seeing his family’s hut burn but was unable to say precisely where he was born.

4 Wikström, 1971, pp. 272-314; Danielsson, 2021, p. 47

5 Östlund, 2017, pp. 71-91. Badin’s story was recounted in later novels after he died in 1822. For instance, Magnus Jacob Crusenstolpe, Der Mohr oder das Haus Holstein-Gottorp in Schweden. Aus dem Schwedischen, Berlin, Morin, 7 vols., 18421844, whose unreliable accounts of Badin at the Swedish court racially stereotyped him as a wild, untamed African savage. Cf. Lowe, 2005, pp. 17-46, especially p. 18, for the question of black Africans who, if they conformed to norms of dress and behaviour while assimilating European cultural life, were able to neutralise stereotypes of black Africans as “savages”, projecting themselves as accepted, “honorary” Europeans who happened to have black skin. This is precisely the case of Badin, who grew up in the intimate circles of the Swedish royal family to become a respected citizen of Stockholm and accepted in elite circles.

6 This name derives from the French badiner, meaning to joke or banter; badinage means witty remarks. In French badin is a joker, fool or pranskter.

7 In Swedish she was called Lovisa Ulrike. In German, Luise Ulrike. She signed her letters, Ulrike. I have opted for the English spelling of Louisa Ulrika.

8 Drottningholm was built by King Adolf Fredrik’s great aunt, Queen Hedvig Eleonora, designed by the architects Nicodemus Tessin the Elder and his son. In 1744, soon after she arrived in Sweden, ownership was transferred to Princess Louisa Ulrika. It became her favourite and primary residence, where she housed her comprehensive collections of paintings, Old Master drawings, antiquities, coins, medals, books, historical documents, and natural history specimens. Drottningholm remained the focus of Louisa’s intense patronage for thirty years, her energies invested in laying out its gardens, outfitting its interiors and adding buildings, including a Chinese pavilion.

See Laine, 1998, pp. 493-503.

9 This drawing is discussed and illustrated in Östlund, 2017, fig. 4.4 without mention of its present location. According to Östlund, Berndes added a poem (on the reverse?) to Badin’s image: “Born among slaves he wandered among them; till the approach of light drove away darkness: and then it was that transported its luster and warmth, Adolf Ludwig Gustaf Fredrik Albert Badin Cou[s]chi, wished to die as one truly free”.

10 Pred, 2004, p. 77. Through his court connections, Badin joined several secret societies in Stockholm, such as Per Bricole, where he became the second-highest ranking fellow and the Freemasons in 1773, which included his royal foster brothers King Gustav III and Princes Karl and Fredrik Adolph. He actively engaged in their philanthropic projects, donating to these fraternities. Cf. Par Bricoles Gustavianska Period. Personalhistoriska Anteckningar till den Äldsta Matrikeln, Stockholm, Hasse W. Tullbergs Förlag, 1903, p. 86, no. 704: “Badin, Adolph Ludwig”.

11 For black pages at Ancien Régime German courts consult Honeck, Klimke, and Kuhlmann, 2013, p. 10, addressing the question of visibility and mobility of black servants in German aristocratic elite circles; some black people, like Badin, even attaining successful court careers in Central Europe.

12 Before this, Badin had been the queen’s footman and butler.

13 A 1744 portrait of Louisa Ulrika as Princess of Prussia painted by Pesne at the time of her marriage in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, inv. no. 53.1. Consult online: https://recherche.smb.museum/detail/870040/luise-ulrike-prinzessin-von-preußen-1720-1782?language=de&question=Antoine+Pesne&limit=15&sort=relevance&controls=none&collectionKey=GG*&objIdx=7 (accessed 15 December 2023).

14 Louisa Ulrika’s education and upbringing and that of her siblings at the Prussian court are outlined in Oster, 2007. Louisa’s eldest sister, Wilhelmine of Prussia (17091758), Margravine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, became an active patron of the arts, an accomplished musician, composer, painter, poet and playwright. She engaged in significant building projects while transforming her lavish court at Bayreuth into the intellectual centre of Central Europe. See also Rivière, 2003, pp. 41-62.

15 Dermineur and Svante, 2016, pp. 84-96; Dermineur 2015.

16 Dermineur, 2017, p. 71.

17 Levertin, 1902; Laine and Brown, 2006, pp. 199-201.

18 Laine and Brown, 2006, p. 245.

19 Present whereabouts unknown. Oil on canvas (after a pastel), 67 x 52 cm.

20 See Dermineur, 2017, p. 10, for Louisa’s interest in the Prussian army, impacted by her father, Frederick Wilhelm I and the multiple uniforms he wore, who self-fashioned himself as an absolute army officer, shunning court costume and p. 110 for the fabrics, lace and pearls Louisa ordered from Paris and Berlin for her ceremonial clothes made for her coronation in 1751. This splendid silver dress with embroidered gold crowns she designed still survives in Stockholm in the Royal Armoury (National Historical Museums, SHM, Livrustkammaren). Consult online: https://commons. wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lovisa_Ulrika_av_Sveriges_kröningsklänning_från_1751_-_ Livrustkammaren_-_13124.tif (accessed 15 December 2023).

21 The pentimenti around the top of Badin’s head are visible in the X-rays taken by Art & Research Photography in Amsterdam in January 2024. Also slight changes in the nose and lips are visible, which points towards Björk having difficulty in copying a portrait of a man with non-European features.

22 In December 1763, the Swedish Royal Chancellor Count Fredrik Sparre pejoratively observed in his diary that Badin was short: “[…] as a little dwarf, although not unpretty”. Cf. Pred, 2004, p. 215, n. 52.

23 Pastel on paper, 74 x 57 cm, inv. no. NMGrh 1455. For payment made by Queen Louisa to Lundberg for Badin’s pastel, see the published dissertation by Laine, 1998, p. 62, who cites the queen’s account books in which this commission appears.

24 An identical red and white chessboard made of gold-plated leather, perhaps the same one depicted in this portrait, with Queen Louisa’s monogram, was recently purchased in 2017 by the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. Designed by the queen’s bookbinder, Christopher Schneidler (1721-1787), it is dated 1771-1782. See Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv. no. NMK 111a/2017. Consult online: https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ ResultListView/result.t1.collection_list.$TspTitleImageLink.&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=0&sp=3&sp=SdetailList&sp=300&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=T&sp=317 (accessed 15 December 2023).

25 Alfredson, 1987, pp. 85-89.

26 Östlund, 2017, pp. 71-91.

27 Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, oil on canvas, 74 x 58 cm, inv. no. NMDrh 35. Signed and dated: 1775

28 After Queen Louisa died in 1782, this residence was managed by her daughter Princess Sophia Albertina. In the 19th century, it became a prison and military barracks (from 1802-1888), with many sectors destroyed and the former royal furnishings and contents dispersed. Very little of the original palace stands today. Badin’s pastel portrait remained in Fredrikshov Palace, was then transferred to Gripsholm Castle at an unknown date and the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm in 1866.

29 Badin’s pastel cited in the queen’s 1782 post-mortem inventory located in Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Kungliga archiv, Bouppteckningshandlingar, Lovisa Ulrika, vol. 270, 16 September 1782, unfoliated: “Bilder. Badens porträt en pastel af Lundberg - 50 [riksdaler]”. Cf. Laine, 1998, pp. 243-244. After Queen Louisa’s death, Badin’s pastel was relocated to Gripsholm and in 1866 entered the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm.

30 These two pieces are located today in Tullgarn Palace, Nyköping; catalogued as étagère (inv. no. HGK401) and writing desk (inv. no. HGK1249), respectively. Cf. Laine, 1998, p. 243, fig. 70. For the analyses of the Asian lacquer panels (hinoki and Ryukyuan urushi) inserted by Dahlin, see Maria Brunskog and Tetsuo Miyakoshi, “A Colourful Past: A Re-examination of a Swedish Rococo Set of Furniture with a Focus on the Urushi Components”, in: Studies in Conservation (2020): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00393630.2020.1846359 (accessed 15 December 2023).

31 Olaf Fridsberg, Portraits of Illustrious Men, with Short Biographies of Their Lives, written by Mme la Comtesse de Tessin, 1760s, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, watercolour on paper, 23 x 19 x 5.5 cm, inv. no. NMH 145/1960.

32 Consult the exhibition catalogue, Treasures from the Nationalmuseum of Sweden: the collections of Count Tessin, edited by Colin B. Bailey, Carina Fryklund, John Marciari, Magnus Olausson, and Jennifer Tonkovich, New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, 2017.

33 I posit this may be an unknown self-portrait of Rosalba Carriera, which Count Tessin may have purchased in Paris at the sale of the court banker Pierre Crozat in 1741. Carriera lived in Crozat’s residence between 1720 and 1721.

34 Dated 1761. Pastel on paper, 64 x 52 cm, inv. no. NMB 126. Consult online: https:// collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=24067&viewType=detailView (accessed 15 December 2023).

35 Laine and Brown, 2006, pp. 129-135.

36 Amsterdam, Zebregs&Röell Fine Arts & Antiques, oil on canvas, 74.5 x 61 cm. One of four oil sketches or preparatory studies commissioned by Pope Clement XI Albani (1649-1721) for the mosaic decoration project on the pendentives of the chapel of the Baptistery in St. Peter’s.

37 Forsstrand, 1911, p. 127; Pred, 2004, pp. 92-93. For Badin’s theatrical engagements, see Willmar Sauter and David Wiles, The Theatre of Drottningholm – Then and Now. Performance between the 18th and 21st Centuries, Stockholm, Stockholm University, 2014.

38 Amsterdam, Zebregs&Röell Fine Arts & Antiques, pen, ink and watercolour on paper, 25.2 x 18.7 cm

38 Austin, 1967, pp. 126-127.

39 For more on Angelo, consult the 2011 exhibition catalogue online: https://issuu. com/wienmuseum/docs/wien_museum_ausstellungskatalog_ang/19 (accessed 15 December 2023).

40 See Maupertuis’ preface (unpaginated). “Je m’étois trouvé la veille dans une maison où l’on avoit apporté le Negre blanc qui est actuellement à Paris. On nous assura que cet Enfant était né de parens très-noirs; & chacun raisonna à perte de vuë sur ce prodige” / “I found myself the night before in a house where they have brought the white Black who is presently in Paris. We were assured that this child was born of very black parents, and each & everyone reasoned as far as the eye could see about this prodigy” [author’s translation].

41 Pastel on paper in an ornate Rococo frame, 75 x 56 cm, inv. no. NMB 1674. Inscribed in French: “Mapondé, né d’un nègre et d’une négresse à Cabende, de nation Moyo, est a esté traitté au dit Cabende, coste d’Angolle, le 15 Janvier 1743. Peint par J.-B. Perroneau en 1745” / “Mapondé, born of a negro and negress at Cabende, of the Moyo nation, and who was treated at the said Cabende, on the coast of Angola, 15 January 1743. Painted by J.-B. Perroneau in 1745” [author’s translation]. Transferred from Drottningholm Palace to the Nationalmusum in 1865. Cf. Léandre Vaillat and Paul Ratouis Limay, J.-B. Perronneau. Sa vie et son ouevre (Paris-Brussels: G. van Oest, 1923), p. 13, pl. 10.

42 Danielsson, 2021, p. 48.

43 Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, c. 1760, pen and ink on paper, 19.6 x 15 cm, inv. no. NMH 444/1995. Inscribed on the reverse: “Badin négre de la reine Louise Ulrique de Suede, dessiné 1757” (“Badin, Queen Louisa Ulrika of Sweden’s black”).

45 Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, c. 1760, pen and ink on paper, 36.8 x 26.5 cm, inv. no. NMH 543/1995.

46 Hubert L’Archevêque was a Swedish sculptor and director of the Swedish Academy of the Arts, from 1768 to 1777.

47 Another Swedish court artist, Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814), also sketched Badin’s head, in profile; a caricature which grossly underscored his African appearance, stereotyping Badin as a comic figure. See Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, c. 1775, pencil on paper, 32 x 20.6 cm, inv. no. NMH 1853/1875 verso. Consult online: https:// collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultListView/ result.t1.collection_list.$TspTitleImageLink.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=0&sp=3&sp=SdetailList&sp=0&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=T&sp=6

16

(accessed 15 December 2023). Cf, Pred, 2004, p. 89.

48 Danielsson, 2021, p. 48.

49 See note 2 above for Badin’s diary. One French play noted by Badin in his diary on page 14, upper right-hand corner, was possibly the comedy in five acts, Les Femmes Savantes, written by Molière in 1672. The second book he noted was that by the prolific, celebrated French author Catherine Durand (1670-1736), who published in 1714, Henry Duc des Vandales, histoire veritable (Paris: Chez Pierre Perrault). The history of the Capetian King Henry I of France (1008-1060), whose reign was marked by struggles against rebellious vassals, which must have fascinated Badin because his patroness, Queen Louisa, experienced similar problems during hers. Badin also had a personal ex-libris, the letters of his name in gold. Cf. Forsstrand, 1911, p. 137 and p. 136 for the printed list of Badin’s books sold at auction in Stockholm on 30 October 1822.

50 Roy-Di Piazza, 2023, p. 6, for Swedenborg’s thesis that sub-Saharan Africans were superior to Europeans and condemned European missionaries for intruding on African lands.

51 Basir, 2015, p. 72 and Roy-Di Piazza, 2023, p. 6 for a quote from Badin’s diary: “Faith probably without hope, is a promise without impact; but when the deed ratifies faith, hope, religion becomes a goodness […] the one who believes in me, the deeds I perform, those he shall also perform; and perform deeds greater than them: for I go to the Father. Can great deeds of kindness fulfil one, like enhancing my followers’ earthly and eternal felicity. Those are my thoughts about this gospel, I do not ask the doctor in theology, but my question is submitted alone to the well enlightened in the practicing of Christianity”.

52 As Badin wrote, his life between 1762 and 1771 was considered by him to be one of a “wild man or animal”. Cf. Wikström, 1971, p. 275; Pred, 2004, who quotes from Badin’s diary dated 1807-1810, p. 8: “During his childhood he [Badin] was nursed to imbibe the wild in man and thereby embarked into a world of trials. His life resembled that of the wild animals, until it was corrected. That was me in the years 1762 to 1771”.

53 Queen Louisa’s sojourn in Berlin was financed by her elder brother Frederick, which cost him a small fortune. Her expenses are detailed in his surviving account books, Monatliche Schatullrechnungen, 1772, Ms. 779, fol. 9v: “die Unkosten der Königin von Schweden”. Consult online: https://quellen.perspectivia.net/de/schatullrechnungen/ ms_779_tr (accessed 15 December 2023).

54 Dermineur, 2017, p. 213; Danielsson, 2021, p. 54.

55 Schück, vol. 2, 1919, p. 82: “Badin est ici comme à Stockholm; c’est le joujou de tout le monde. La Reine et les Princesses le font venir chez elles, et il est tous les jours invité, soir et dîner, en ville”.

56 See the recent 2023 exhibition held at Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin: Schlösser Preussen. Kolonial Biografien und Sammlungen im Fokus. See the accompanying brochure: https://www.spsg.de/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/SPSG_Schloesser-Preussen-Kolonial-Flyer.pdf, and the film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSxp4_lf59k&t=17s (accessed 15 December 2023).

57 Wikström, 1971, p. 280.

58 See Pred, 2004, p. 78, for Badin being ordered by his adopted brother, King Gustav III, to spy upon members of their Freemason’s Lodge.

59 The obliteration of his mother’s correspondence and papers infuriated King Gustav III, who seriously reprimanded Badin for his actions, to which Badin responded that he could not contradict his dead mother’s last wishes and had to obey his former protector. Cf. Bonde, 1902, p. 411 and p. 422; Forsstrand, 1911, p. 131.

60 Forsstrand, 1911, p. 132; Wikström, 1971, pp. 285-288; Pred, 2004, p. 94.

61 Uppsala, Uppsala University Library, Erik Wallers Autografsamling, Stockholm, 21 October 1782, ink on paper, 320 x 200 mm, shelfmark: Waller Ms se-00156. Signed: Adolph Ludwig Badin. Badin rented this home from Frederik Munck.

62 Fehrman was a student of the sculptor Pierre Hubert L’Archevêque, who established his career in Stockholm, executing portrait and commemorative medals for clients, which included King Gustav III, who patronised the medallist. Badin knew and met Fehrman at court.

63 Uppsala, Gustavianum, Uppsala Univeristy Coin Cabinet (Myntkabinett), 1794, silver, diameter: 50.94 mm. Inscribed obverse: MDCCXCII. Reverse inscribed in Swedish: UPRORISKA WAPEN OMRINGADE MÄSTARN WID MIDNATT II GUSTAF LEFDE SÅRAD XIII DYGN DOG BEGRÅTEN WID FULL MIDDAG XXIX MART / “Rebellious arms surrounded the Master at midnight […; 16 March] Gustaf lived wounded XIII days [.] Died mourned […] at noon XXIX March [author’s translation]”. Cf. Forsstrand, 1911, p. 131.

64 Elisabeth died in 1798. Badin remarried a white Swedish lady, Magdalena Eleonora Norell. Both marriages remained childless.

65 Wikström, 1971, p. 293, n. 56: “Voilà mon bon ami Badien un peute pour tes menus plaisier, j’aisper que votr[e] sant[é] est melieur que l’ anne [année] pance. Vous voigesse [voyer] que [je] noublie pas mes amis abssence [absent]”. Wikstöm quotes the autograph letter he consulted in Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Ericsbergsarkivet, Autografsamlingen, Sverige, Sofia Albertina, vol. 282, unfoliated (no date, no location).

66 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Kungliga arkiv, Bouppteckningshandlingar, Princessan Sofia Albertina, K 387, fol. 110.

A

1770-1790 Collection Royal Livrustkammaren, Stocholm (no. 31869_LRK)

Credit: Livrustkammaren, Livrustkammaren/SHM (CC BY 4.0)

Fig. 17

formal costume of the Swedish court, c.

Fig. 17

formal costume of the Swedish court, c.

About the author

Dr. Annemarie Jordan Gschwend is a Senior Research Scholar and Curator associated with the Centro de Humanidades (CHAM) in Zurich, Switzerland and Lisbon, Portugal since 2010. Jordan’s areas of specialisation include Kunstkammers and menageries at the Renaissance courts in Austria, the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal. She is the author of numerous publications: articles, exhibition catalogue essays and books, including, The Story of Süleyman. Celebrity Elephants and other Exotica in Renaissance Portugal (Zurich-Philadelphia, 2010). With Kate Lowe, Jordan co-edited the award-winning book The Global City. On the streets of Renaissance Lisbon (Paul Holberton Publishing, London, 2015).

Primary Sources

Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Stafundsarkivet, vol. 29: Relations des évènements en Suède, les années 1771 et 1772, faite par le maréchal de la cour Mr S. A. Piper à la Reine Louise Ulrique de Suède

Stockholkm, Riksarkivet, Kungliga archiv, Bouppteckningshandlingar, Lovisa Ulrika, vol. 270 (16 September 1782)

Stockholkm, Riksarkivet, Kungliga archiv, Bouppteckningshandlingar, Stockkolm, Riksarkivet, Princessan Sofia Albertina, K 387

Select Literature

Hans Alfredson, ‘Svart spelar vit. Gustaf Lundbergs porträtt av Badin’, Porträtt. Studier I. Statens Porträttsamling På Gripsholm, edited by Ulf G. Johnsson, Stockholm, Rabén & Sjögren, 1987, pp. 85-89

Paul Britten Austin, The Life and Songs of Carl Michael Bellman: Genius of the Swedish Rococo, Malmö: Allhem Publishers, 1967

Eric Curtis Muhammad Basir, Badin’s Diary: An English Translation, edited by Sandra Gustafsson. Raleigh, North Carolina, Lulu Publishing, 2015

Carl Carson Bonde, ed., Hedvig Elisabeth Charlottas Dagbok. I. 1775-1782, Stockhom, R. A. Nokstedt, 1902

Susan Danielsson, ‘Gustav Badin: The Afro-Swedish Experience in Eighteenth- Century Sweden’, in: The Saber and Scroll Journal, 10, 1, 2021, pp. 45–61

Elise M. Dermineur, ‘Queens Consort in Premodern Europe. A European Research Project in Progress’, in: Frühneuzeit-Info, May 2015: https://fnzinfo.hypotheses. org/406

Elise M. Dermineur, Gender and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Sweden. Queen Louisa Ulrika (1720-1782), London & New York, Routledge, 2017

Elise M. Dermineur and Norrhem Svante, ‘Luise Ulrike of Prussia, Queen of Sweden and the Search for Political Space’, Cultural Encounters as Political Encounters: Queens Consort and European Politics, c.1500-1800, edited by Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly and Adam Morton, London & New York, Routledge, 2016, pp 84-96

Julie Duprat, ‘Gustav Badin, un homme éclairé’, 2018: https://minorhist. hypotheses.org/196

Hubert Daunoy, ‘Le pastelliste Gustave Lundberg’, in: Le Figaro. Supplément Artistique Illustré, 1929, pp. 266-267

T.F. Earle and K.J.P Lowe, eds., Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005

Karin-Feuerstein-Prasser, ‘Luise Ulrike. Königin von Schweden (1720-1784)’, in: Friedrich der Grosse und seine Schwestern, Munich, Piper Verlag, 2014, pp. 195-229.

Carl Forsstrand, Sophie Hagman och hennes samtida; några anteckningar från det gustavianska Stockholm (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1911).

Annemarie Jordan Gschwend, ‘Images of Empire: Slaves in the household and court of Catherine of Austria’, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, eds. Thomas Earle and Kate Lowe (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005), pp. 155-180

sociabilité entre cour et ville’, in:

My Hellsing, ‘Stockholm aristocratique à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Hôtels et sociabilité entre cour et ville’, in: Noblesses et villes de cour en Europe (XVIIe- XVIIIe) La ville de résidence princière, observatoire des identités nobiliaires à l’époque moderne, edited by Anne Motta and Éric Hassler, Rennes: Presse universitaires de Rennes, 2022, pp. 1-29

Mischa Honeck, Martin Klimke, and Anne Kuhlmann, eds., Germany and the Black Diaspora. Points of Contact, 1250-1914, New York, Berghahn, 2013

Olaf Jägerskiöld, Lovisa Ulrika, Stockholm, Wahlström & Widstrand, 1945

Paul H. D. Kaplan, ‘Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography’, in: Gesta, 26, 1, 1987, pp. 29-36

Peter Kasper, Das Reichsstift Quedlinburg (936-1810). Konzept-Zeitbezug- Systemwechsel, Göttingen, V & R press, 2014

Merit Laine, ‘En Minerva för vår Nord’: Lovisa Ulrika som samlare, uppdragsgivare och byggherre, Stockholm, M. Laine, 1998

Merit Laine, ‘An Eighteenth-Century Minerva: Lovisa Ulrika and Her Collections at Drottningholm Palace 1744-1777’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 31, 4 (Summer 1998), pp. 493-503.

Merit Laine and Carolina Brown, Gustaf Lundberg 1695-1786, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 2006

Merit Laine and Ellinor Lindeberg Moberg, ‘An 18th Century Frame’, in: Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm, 22, 2015, pp. 209-212

Ola Larsmo, ‘Skuggan av Badin: några dagboksanteckningar av Gustav III’s morian’, in: Bonniers litterära magasin, 65, 6, 1996, pp. 4-9

Oscar Levertin, Gustaf Lundberg. En Studie, Stockholm, Aktiebolaget Ljus, 1902

K.J.P. Lowe, ‘Visual representations of an elite: African ambassadors and rulers in Renaissance Europe’, Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, edited by Joaneath Spicer, Baltimore, Walters Museum of Art, 2012, pp. 98-115

K.J.P. Lowe, ‘The stereotyping of black Africans in Renaissance Europe’, in: Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, edited by T. F. Earle and K. J. P. Lowe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005, pp. 17-46

Edvard Matz, ‘Badin – ett experiment i fri uppfostran’, in: Populär Historia, 15 March 2001: experiment-i-fri-uppfostranhttps://popularhistoria.se/sveriges-historia/1700-talet/badin-ett(accessed 15 December 2023)

Joachim Östlund, ‘Playing the White Knight. Badin, Chess, and Black Self- fashioning in Eighteenth-century Sweden,’ in: Migrating the Black Body: The African Diaspora and Visual Culture, edited by Leigh Raiford and Heike Raphael- Hernández, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017, pp. 71-91

Uwe A. Oster, Wilhelmine von Bayreuth. Das Leben der Schwester Friedrichs des Großen, Munich, Piper Verlag, 2007

Marc Serge Rivière, ‘‘Divine Ulrique’: Voltaire and Louisa Ulrica, Princess of Prussia and Queen of Sweden (1751-1771)’, Irish Journal of French Studies, 3, 2003, pp. 41-62

Vincent Roy-Di Piazza, ‘Enslaved by African angels: Swedenborg on African superiority, evangelization, and slavery’, Intellectual History Review, 33, April 2023, pp. 1-31

Henrik Schück, Gustav III:s och Lovisa Ulrikas brevväxling, Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, vol. 2, 1919

Lars Wikström, ‘Fredrik Adolph Ludvig Gustaf Albrecht Badin-Couschi: Ett Säll- samt Levnadsöde’, in: Släkt och Hävd, 1, April 1971, pp. 272-314

18

18

Renaissance experiment-i-fri-uppfostran

Fig. 18

A jacket and a vest worn at the Swedish court, c. 1770-1780 Collection Royal Livrustkammaren, Stocholm (no. 19227_LRK & 31870_LRK)

Credit: Livrustkammaren/SHM (CC0)

Published by Guus Röell and Dickie Zebregs

Tefaf 2024

Maastricht

6211 LN, Tongersestraat 2

guus.roell@xs4all.nl

tel. +31 653211649 (by appointment only)

Amsterdam

1017DP, Keizersgracht 541-543 dickie@zebregsroell.com

tel. +31 620743671 (by appointment only)

Instagram @zebregsroell

More images and further readings can be found at www.zebregsroell.com

Photography

Michiel Stokmans

Design

A10design

Printed by Pietermans Drukkerij, Lanaken, Belgium

20

Fig. 17

formal costume of the Swedish court, c.

Fig. 17

formal costume of the Swedish court, c.