michael sugich

a traveler met the Angel of Death. “Where are you headed?” the traveler asked. The Angel replied, “I have been sent by God to such and such a city to take one thousand lives.” There was a plague in that city. Sometime later the traveler met the Angel of Death on the way back from the city. He said to the Angel, “You told me that you were sent by God to take one thousand lives, but I have heard that five thousand citizens perished.” The Angel of Death replied, “I did take only one thousand lives. The other four thousand died from fear.”

Our age is marked by fear. We’re all living through a prolonged period of uncertainty and constriction: lockdowns, layoffs, closures, bankruptcies, the zero-sum mindset that is breaking democracy, and a grim reaper promising to reappear in perpetual war and in contagions. Employment, schooling, rent, mortgages, car payments, taxes, health care, and all the heavy demands that loom up at us can easily induce depression, stress, anxiety, and fear—most of all fear of insolvency and poverty.

I have found that what we most fear, adversity itself, can be the best teacher, as humbling and painful as it can be, because one is rendered helpless and in need, which is, in fact, our true condition. Only when we have reached the end of our tether and are forced to give up our will do we see marvels. During such times, an extraordinary dynamic is set in motion, and we witness the oneness of action and existence as God moves us through His creation, responding to our need in real time, and to the needs of others, including our worldly benefactors. “States of need,” wrote the thirteenthcentury jurist and Sufi master Ibn ‘Aţā’ Allāh, “are gift-laden carpets.”

My own gift-laden carpets have been many. I will share three below.

Fifty years ago, my friend Daniel Abdal-Hayy and I were sent on a fool’s errand to the Bay Area in California to set up a kind of community center in Berkeley. We arrived with pocket money but not enough to pay for accommodations. Nor did we have a clue as to how we were going to raise the security deposit and first and last months’ rent for a property that could serve as a decent-sized gathering place. I didn’t know a soul in Northern California. The souls Hajj Abdal-Hayy knew were from his previous life among the Beat literati. He made a call to fellow poet Allen Ginsberg, but the only thing Ginsberg wanted to know was whether Abdal-Hayy was… celibate. We passed by City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, and Abdal-Hayy gamely hit up his old mentor, the poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti. We left empty-handed. In retrospect, this must have been a humiliating exercise for the former rising star of the City Lights set, now reduced to scrounging for cash and sleeping in a used car.

The used car was mine. Every evening, we would find an empty street in some San Francisco neighborhood—Potrero Hill was a favorite landing place—park my hideous (but trusty) mouthwash-green 1963 Plymouth Valiant, and laugh ourselves to sleep, switching places every day between the relatively comfortable back seat and the front

Muha MM ad u . Faruque

it is so M ewhat puzzling that while the vast majority of the world (around 80 percent) believes in some form of supernatural transcendence, the dominant view in many scientific and philosophical circles is that those who affirm God’s existence bear the burden of proof. Meanwhile, atheists, who deny God’s existence, need not prove God’s nonexistence, because theirs is the default position; belief in God is the extraordinary claim. This assumption gets reinforced by the widespread notion that atheists and agnostics are the “normal” people, but this idea is contradicted by the beliefs of most human beings worldwide. The paradox begs the question: Shouldn’t the burden of proof rightly rest on those who deny God’s existence?

Nonetheless, the rise of scientism, agnosticism, and atheism in recent times warrants rational debates about the existence of God or ultimate reality. New Atheist writers such as Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Lawrence Krauss, Leonard Mlodinow, and others frequently invoke the authority of science (often equating it with reason) and point out that our best scientific theories make no reference to God; thus, naturalism— the belief that reality consists only of the physical world and that science is the best way to understand it—must be true.1 These writers assume that empirical and experimental science is the only genuine form of knowledge—a highly controversial metaphysical presupposition not shared by all scientists or based on any “evidence.” With this assumption, they respond to traditional arguments for God’s existence with a wide range of counterarguments. For example, they contend that if God is the cause of everything, then God Himself must have a cause, which leads to the problem of infinite

Thomas h ibbs

in a pivo T al scene in the recent film A Complete Unknown, a young Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet), celebrated as a voice of the 1960s protest movement, complains about the expectation that he should keep playing popular songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” for the rest of his life. The film, which covers Dylan’s early career, culminates with his famous 1965 performance at the Newport Folk Festival, in which he repudiates both the acoustic musical style and the standard political content of the folk revival movement.

The pivotal moment represented in the film, when Dylan scandalized his folk fans, established a precedent that would be repeated regularly over Dylan’s long career—his penchant for asserting his artistic independence from any external influence. Dylan turned from folk to rock, from secular to religious and back again, from pleasing audiences by repeatedly singing hit songs to challenging them by performing obscure songs from his repertoire.

Dylan’s insistence on the integrity of art—its freedom from external compulsion—

Fiddler, Leonid Solomatkin, ca. 1850

As A d Isl A m

sc I ence A nd rel I g I on have had a complicated relationship for centuries. These two subjects fascinated me growing up. As a curious child drawn to nature, I would inwardly question the how and why of the natural world. How did the universe form? Where did the stars, constellations, and our planet with all its wondrous beauty come from? How did humanity start? What is the purpose of our lives? Is there a God? What happens after we die? As someone who loved to read, I would pore over books on science and religion to satisfy my curiosity. Science opened my eyes to how nature worked, while religion offered a perspective on why things existed. Each provided its unique worldview and sounded satisfactory to my budding intellect. In my youthful, inexperienced mind, shielded from Western philosophical debates between the two, science and religion could coexist. I did not see any conflict. My proclivity for mathematics and the exact sciences led me to pursue a career in engineering. After my undergraduate degree, I moved to the United States for several

Angel Ad A ms P A rh A m

This is an edited version of an address on beauty that sociologist and educator Angel Adams Parham delivered at the 2024 Zaytuna College Commencement.

be A uty. if you remember nothing else from today’s talk—and I’m aware of how forgettable many such speeches are—remember Beauty, as this will be my first and last word. Among the transcendentals, Beauty is often left for last: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. It’s often given less attention, or actively avoided, because it’s perceived to be frivolous at best or dangerously seductive and deceptive at worst. But Beauty has a transformative power to heal and to lead us toward Truth and Goodness when other means fail us. We must not, therefore, underestimate the life-giving importance of Beauty.

Let me tell you a story. Here’s the portrait I want you to paint in your mind’s eye: There are vacant lots, weeds growing with abandon. Old tires tossed here and there, black blights on neglected lawns. Children, nevertheless, play in the streets, a bit bedraggled but full of energy, still filled with hope, and taking delight in the smallest things. Walk down this street with me, and you will see that it is quite a different story with the adults. Many of them look back or down with a darkened gaze. Some, desperately hungry, hunt for more of what they shouldn’t have on streets too eager to give what will destroy.

Standing Firm, Youssef Ismail

Oubai Elk E rdi

I have not made them witness the creation of the heavens and the earth, nor their own creation.

qur’an 18:51

History, if viewed as a repository for more than anecdote or chronology, could produce a decisive transformation in the image of science by which we are now possessed.

th O mas kuhn

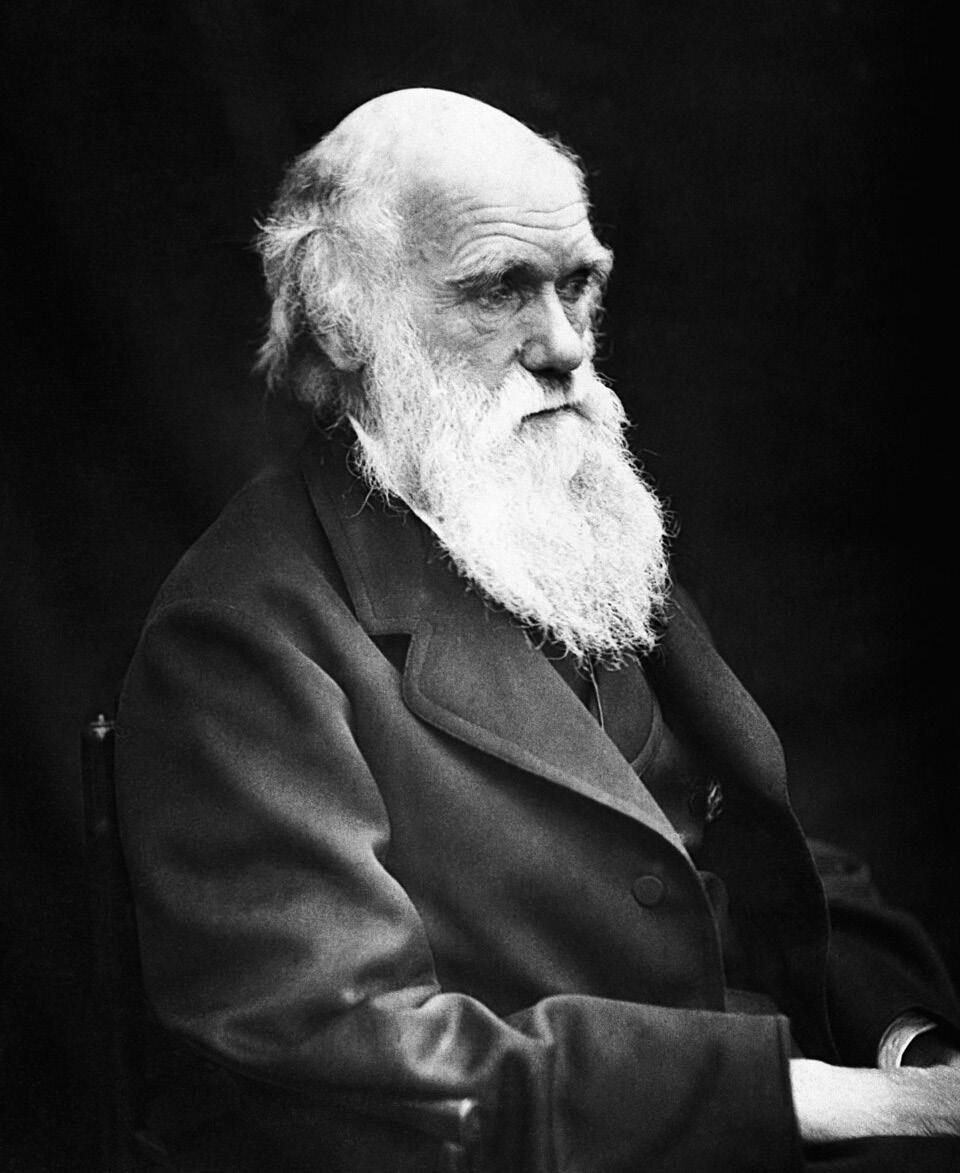

think “charl E s darwin” or feed the name into a search engine and there turns up a mild-mannered, heavy-bearded, elderly gentleman in a three-piece suit. The man we see, typically cast in sepia or gray tones, broadcasts sagacity. We might as well be staring at the Victorian incarnation of a Greek philosopher. No paraphernalia, no backdrop—no context—situates him. Few have ever met a younger Darwin or would recognize him if they did. An elementary school or literary encounter might portray him “as a naïve, innocent, school-boyish, outdoor, nature-loving traveller and

Charles Darwin,

1869

Nasri N r ouzati, Hamza Yusuf, a N d a is H a s ub H a N i

Nasrin Rouzati’s book, titled Trial and Tribulation in the Qur’an: A Mystical Theodicy, examines Qur’anic teachings on the providential purpose of suffering in our lives on earth, something the prophets experienced more than most. This conversation with the author, recorded during Ramadan 2024 as part of the First Command Book Club series, was hosted by Hamza Yusuf and included Zaytuna College vice president Aisha Subhani. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Hamza Yusuf: Our scholars give seven reasons for writing a book, and one of them is that it hasn’t been written. This book, as far as I can tell, wasn’t written before you wrote it. It’s a profound reflection on something central to the Qur’anic narrative, and surprisingly, many people seem to completely miss it. I want to begin by asking you, What compelled you to write this book?

Nasrin Rouzati: The driving force behind my research and writing was this existential question that I always had. As human beings, we all go through different experiences. Some experiences bring us delight and happiness, even though they may be shortlived, and other experiences bring us sadness, despair, suffering, and anxiety. When

A Sanctuary, Lebanon, Askia Bilal

Seyyed Ho SS ein n a S r and Munjed M. Murad

t H e environ M ental cri S i S is not the result of only material causes, since it is also rooted in a spiritual crisis that arose first in the modern West, although few realize this truth.1 In the midst of much discourse and concern about environmental degradation today, most people in the West, and many in the Islamic world, believe that the solution to the environmental crisis lies simply in a wise and correct application of modern science and technology and a wise and correct practice of modern economics. The environmental crisis, however, is not only a natural and material crisis; it is grounded in a spiritual and intellectual crisis that began with modernism itself.2 This crisis began in the West and has now spread to the whole globe, including the Islamic world, which is not only a passive recipient of environmental pollution but is also itself a transgressor against nature, having actively adopted modernist modes of thought, action, and production. To create an Islamic environmental program on any level, Muslims must pay attention not only to material and social elements, but above all to the spiritually and intellectually false understanding of nature as a secular entity rather than God’s creation, and they must revive authentic Islamic teachings concerning God’s creation and man’s relation to it.3

Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, East Java, Indonesia