The original Module Magazine was founded at the Syracuse University department of architecture in the 1950’s, serving as a record of the year, cataloging student architectural projects, architecture events, class activities, and those who are graduating. We hope by adopting the name to continue the rich history of student writing and discussion at the University and situate it within the modern context.

Module 01 - Destruction

Board Members

Zach Ehrenreich

Editor in Chief

Isabela Santana Editor in

Chief

Anita Yasinska Editor

Rabi Qiu

Editor

Kelly Lopez

Graphic Designer

Violet Reichel

Promotions Chair

Lewis Miller Treasurer

Edgar Rodriguez Faculty Advisor

Architecture has a long history of destruction and reformation. Destruction can act as positive metamorphosis, or as a necessary aspect to reformation, symbolizing beginning anew. However, destruction can also act as a tool of the unrelenting politics of progress, destroying communities and critical architectural works—as in the case of the destruction of Penn Station and modernist Tabula Rasa planning. More often, this destruction causes controversy and discussion both in its time and beyond. To destroy is to decide what is of value, and in that lies an inherently controversial act.

We can further conceptualize our understanding by reshifting our perspective of creation and its intrinsic relation to destruction in a larger aperture. A fundamental tenet of all aspects of architecture is that in order to create, we must first destroy. Trees must be processed, buildings must be demolished. We build upon the rubble of eras past, disputing preservation with modernization. The cycle of creation and destruction is primordial. Forests must be managed, by fire or by forestry, to prevent invasive old growth forests and allow new growth. In biblical canon, Noah builds the ark, his shelter, to save himself from the flood of destruction clearing the world of evil. War fundamentally reshapes landscapes, defining new sites of creation.

In architectural theory, modularity and metabolism prioritize the discarding of diseased and aged elements for the health of the whole: a part must be sacrificed for the good of the greater organism. In model making, we destroy material to produce our model by adding or subtracting, and then we destroy our models to revitalize the space of our desks. In drawing, we destroy light from our slate with graphite, and remove it with rubber, adding or subtracting as we see fit. We work in cycles in which the destruction of the unviable is as important as the making of what is, shaping the world as if it were clay.

In architecture, we must embrace destruction as part of reforming the environment anew. The first edition of Module hopes to address destruction in a new lens, as it relates to our works and writings, considering how destruction affects creation at all scales. We hope you enjoy our first edition.

Sponsors

Syracuse University

Gelman Architecture

Big Bear Gear

Best Regards,

Zach Ehrenreich

8 9 3 5 6

7 1 2 10

4

1INTRODUCTION

Zach Ehrenreich Class of 2029

3

EPHEMERAL STRUCTURES

LA F[i]ESTA

2025 Directed Research

5DESTROYING SPACE

Rabi Qiu Class of 2029

7MIRRORS

Yitang Zhang Class of 2028

9

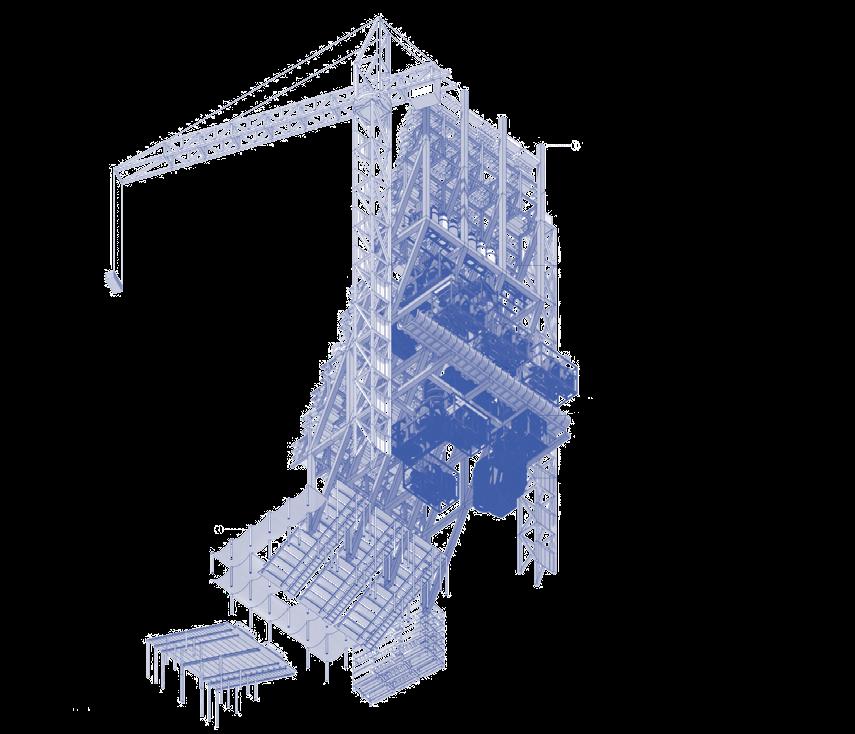

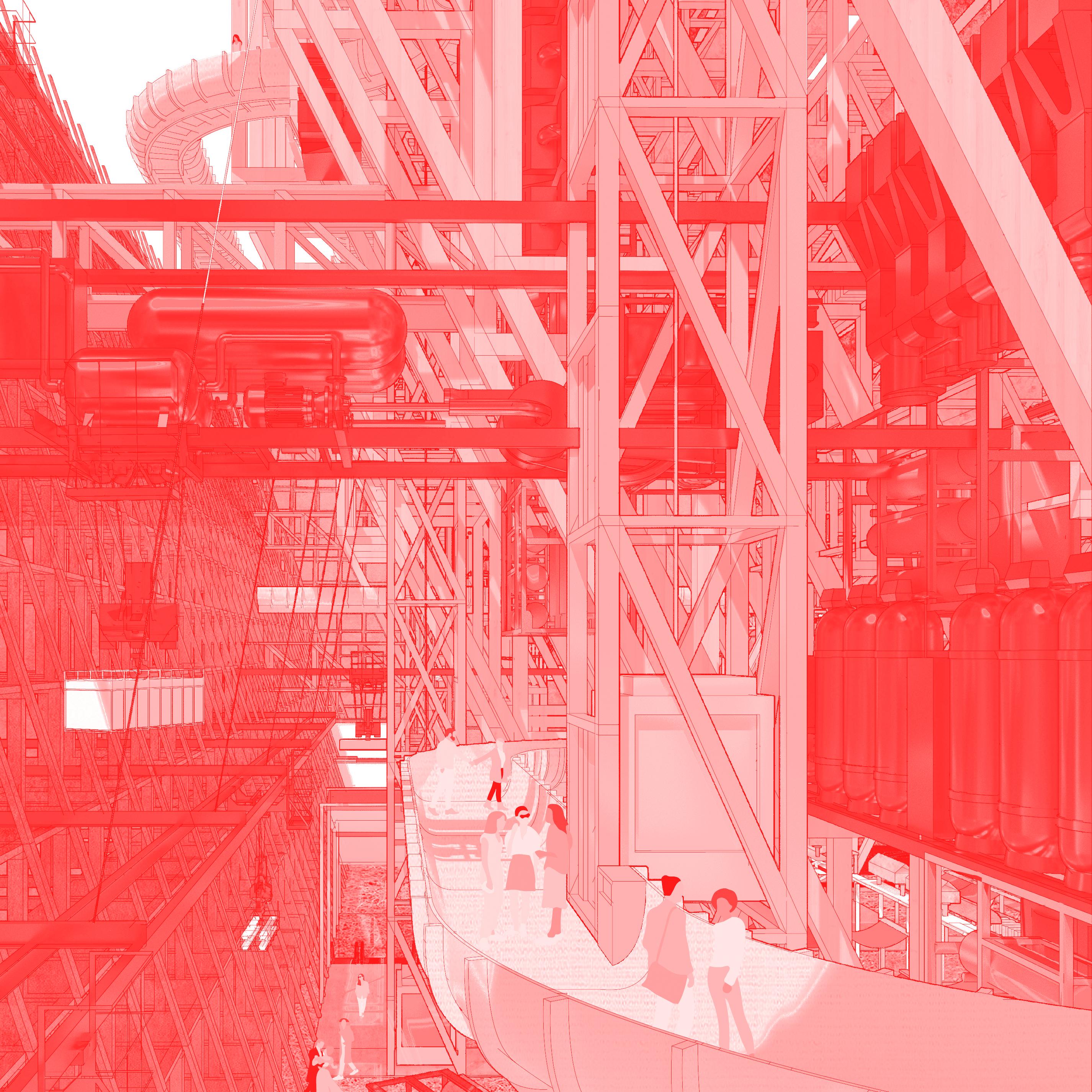

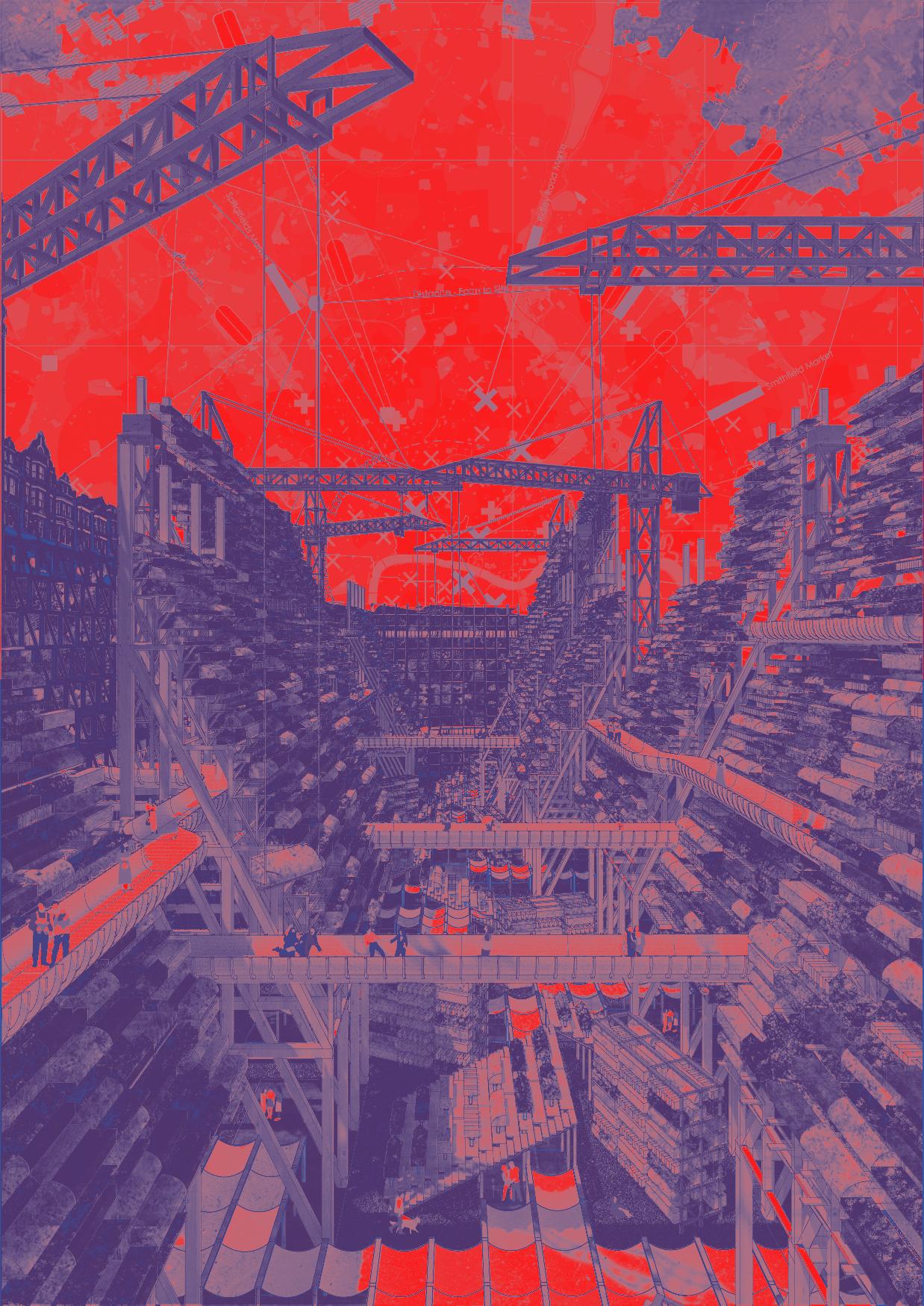

FARMING DEPOT CITY

Yifan Shen, Yue Zhuo, Fei Xiong

Class of 2025

2COMBAT ZONES

Sophie Mays Class of 2029

4

STAIRWELL BETWEEN

Vengkeng Meng Class of 2028

6METABOLISM

Isabela Santana Class of 2029

8INTERVIEW

Anita Yasinska Class of 2029

10 DWELLING

Samuel Piconcik Class of 2029

Schools Designed as Combat Zones: How Preparing for the Worst-Case Scenario Makes it the New Norm

Sophie Mays, ‘29 Architecture Student

In the United States, as of 2024, there is an average of one school shooting every other week of the school year.1 With these issues prevalent and gun control laws and regulations far from being enacted in any way, many schools and community spaces across the United States are prompted to redesign in order to protect their students and community members. However, the social impact that these redesigns may have, while enacted with good intentions, could greatly affect student life in America.

The New Design

One example of a school renovation is Fruitport High School, located on the west coast of Michigan. With a cost of $48 million, the school’s

1 Based on the statistic of 83 school shootings in 2024 and an average of 36 school-weeks per year. Source: Matthews, Alex. “School Shootings in the US: Fast Facts.” CNN, Cable News Network, 11 Feb. 2025.

layout includes curved hallways to break up sightlines, little nooks and half walls to create cover, and impact resistant glass installed into every door and window.2 The design also features a front desk with a view of the single, secure main entrance in and out of the building, described by the architectural firm who designed the space, TowerPinkster, as reminiscent of a “Panopticon”.3 Though intended to create a feeling of security and safety within its walls, the design has the unintended effect of brewing uncertainty.

Designing for violence may address the current safety related concerns surrounding school shootings in America, but changing these spaces that are meant for students to learn and grow in to instead focus on protection shifts the atmosphere of the environment as a whole. For example, adding cover fundamentally recontextualizes the space you’re in- if it exists, it was built for a reason, and since it was built, it was meant to be used. Anyone familiar with a shooting-related video game will subconsciously recognize these spaces as places of danger, where something bad is about to happen and the half-walls that otherwise serve no purpose will fulfill their role. These small design changes recontextualize schools as dangerous combat zones, where cover is necessary and the first thought on any student’s mind should be what they can dive behind should the need arise. Similarly, increasing security in schools, through the single observed Wentrance and exit and addition of extra security cameras—or even in some cases security guards and metal detectors—heightens feelings of anxiety and fear in students, as well as reduces their privacy and comfort levels in the learning environment. Even the reference to the front desk as a ‘Panopticon’ supports this, with the design originally used in prison complexes so one guard could observe every prisoner at once. As the superintendent of Fruitport, Robert Syzmoniak, has stated, the school was designed “so there aren’t too many places where a kid can be

2 Gibson, Eleanor. “Michigan High School Designed to Reduce Impact of Mass Shootings.” Dezeen, 5 Sept. 2019.

3

Aug. 2019.

that the eyes of an adult could not be on that kid”.4 Though these measures were taken to improve safety, they lessen individuality and create a sense of distrust and suspicion that fragments the community, negatively affecting students’ experience.

The Impact

These school redesigns, while having good intentions, fail to target the real root issue of gun violence and instead lean into the narrative of schools as a danger zone that students should be fearful to study in. In preparing for the scenario in which gun violence occurs, and designing around this concept, gun violence further embeds itself in the narrative as an expectation of life in America, an inevitability like any natural disaster or freak accident. Following this logic, these designs promote both the destruction of space and the dismantling of student communities. Walls designed against being torn apart by bullet holes invoke feelings of unsafety and suspicion, with students too focused on survival to create meaningful connections with each other. Structure designed against destruction instead redirects the damage, splintering the threads intertwining the students, further progressing feelings of isolation and the dissolving of a community. Architecture reflects culture, and culture affects architecture. This intertwined and varied interplay between the spaces we spend our day-to-day lives in, and the way in which we interact with each other and ourselves, emphasizes how horrific it is that a place for a 14 year old to learn algebra necessitates hiding places, quick escape routes, and bulletproof glass. There should be no similarities between the spatial relationships of a combat zone and a school, but using these redesigned highschools as examples of the narrative America is telling its students, it is evident that something needs to change. Architecture affects the way we view the world, whether consciously or subconsciously, and the future students of the United States need not grow up learning to expect violence.

4 Chambers, Jennifer. “Michigan School Designed to Foil Shooters: ‘It Slows Them Down.’” The Detroit News, 8 Jan. 2020.

EPHEMERAL STRUCTURES

LA F[i]ESTA, 2025 Directed Research

Instructors: Palladino, Valdevenito

Written by Corrine Soo

LA F[i]ESTA: EPHEMERAL STRUCTURES is a collaborative, design-build project led by faculty members, Rosita Palladino and Magdalena Valdevenito, and twelve fifth-year students taking Directed Research. Its focus lies in studying, developing, and documenting 1:1 scale material assemblies inspired by the findings of archival research on celebrations around the world. The studio will design, build, and assemble temporary installations on-site in the Quad to create a celebration of their own. The event will run for two days, from April 29th - April 30th, and is open to all students, faculty, staff, and the greater Syracuse collective. Themed around graduation, LA F[i]ESTA is not only a showcase of student work, but also a commemorative gathering that marks the culmination of students’ academic journey.

Schedule

The first day features a collective procession that anyone and everyone can join; it begins at the center of the Quad, passes through the Orange Grove, and concludes at Hendricks Chapel. Stationed along the route are student-built installations inspired by global festival architecture and traditions. Each creates a unique, interactive experience for attendees and passersby. Paired with this procession will be a performance by the East Syracuse Minoa Marching Band.

The second day is the final review where the class will walk through the installations once again with critics before having a group conversation — dubbed the Sobremesa — about the event’s successes and failures. In the evening, a collaborative event with the National Organization of Minority Architecture Students (NOMAS) will take place; participants will receive a white paper bag that they can decorate as they like — writing hopes, giving thanks, and sending other wellwishes — before putting a tea light inside and placing the lantern around one of the installations. This will be the culminating act for the two-day celebration.

Throughout both days will be live music, student club meetings, as well as dance and vocal performances by student organizations.

Installations

The first temporary installation, situated at the center of the Quad, marks the start of the LA F[i]ESTA celebration and procession. Six modules made of reclaimed wooden pallets are arranged along a circular path to create a gathering space in the center; it is meant to be a place for people to take a pause from their daily routine and engage in being thankful and reflective. The collection of objects are designed to encourage interaction and play, inviting participants to move through the space in a way that reconnects them with the elements of nature and fosters a sense of grounding and gratitude.

The core material is reclaimed wooden pallets that have been collected, sanded and cleaned-up, partially disassembled, and then reassembled into something new and engaging. The rest of the materials are either hardware — which allows for partial disassembly and a collapsible quality that makes them easy to transport and store — or embellishment to activate user experience. The aim is to take less from nature, minimize human impact, and honor the land we all occupy.

The starting module is a gateway offset from the middle of a main path in the Quad. Its arch form signifies an entrance point, or “passing through,” into this newly imagined space. The rest of the modules represent the five elements, or states of matter, in nature. First is earth: triangular pods are filled with rocks, dirt, and sand for people to step in as a way to reconnect with the land. Next is water: planters are filled with water and foliage, a sign of life, for people to smell and brush their hands over. Afterwards is fire: pallet pieces are spread apart to resemble a hearth; they face inwards toward the center of the installation and act as seating. Then is air: hanging from a totem pole are windchimes for people to listen to. Lastly is space: a portal framing the White Pine Tree, the symbol of peace, invites people to look through as they reflect on their time at Syracuse. Finally, in the center of them all, is an elevated stage for performances that can expand out to double as seats for rest.

The second temporary installation is placed within the Orange Grove, which serves not only as a place where students often congregate to talk or study, but also as the only alumni landmark on campus. Part of the design is inspired by its stone grid that has been and will continue to be carved with the names of alumni. The main theme of this installation is reflection and tradition. It reimagines and revitalizes a Syracuse University tradition that started 20 years ago following a competition to establish a new tradition on campus. It is said that graduating seniors who tie a ribbon, representing a wish, in the Orange Grove during the week before Commencement will have their wish come trueWafter graduation. This ribbon-tying tradition is enhanced when students are brought together to participate in the collective ephemeral act.

The installation includes two pairs of interlocking wooden frames that use a lap joint and a half lap joint for the corner and interlocking connections. The design is meant to minimize the amount of material needed to support the frames at their desired angle, yet still be able to bear the weight of the entire structure. One of the frames has horizontal poles that hold ribbons for all of the graduating seniors, while the other is filled with reflective mylar film. The mirror-like surface produced encourages introspection from students who go to tie their ribbons. Together, the wooden frames serve as a visual symbol of the transition from student to alum as the ribbons in the installation are physically transferred to the trees beside it.

The final temporary installation is positioned in front of the steps of Hendricks Chapel, a landmark that symbolizes graduation and serves as a popular setting for commemorative photos. It is the last stop of the procession, serving as a threshold that graduates, family, and friends can pass through to symbolize the transition to a new stage of life.

The installation is a pair of adaptable structures joined together by banners to create a gate that frames the center of Hendricks. They are made out of dimensional lumber fixed together with metal hardware and dowels. The design keeps the wood at regular lengths as much as possible to minimize waste and increase their ability for reuse. A key component is an adjustable board that can be raised or lowered to serve as either a bench, table, or canopy. The frames can also be rotated or moved to match the intended set-up and function. The flexibility of the installation allows for various uses, including gatherings, casual meetups, and spontaneous celebrations. Its design naturally frames key views and will serve as an aesthetic backdrop for graduation photos, enhancing the ceremonial quality of the space. The installation provides graduates with a special opportunity to capture memorable moments in front of a significant campus location. This combination of symbolism and functionality fosters a sense of community between students, the university, and Syracuse as a whole.

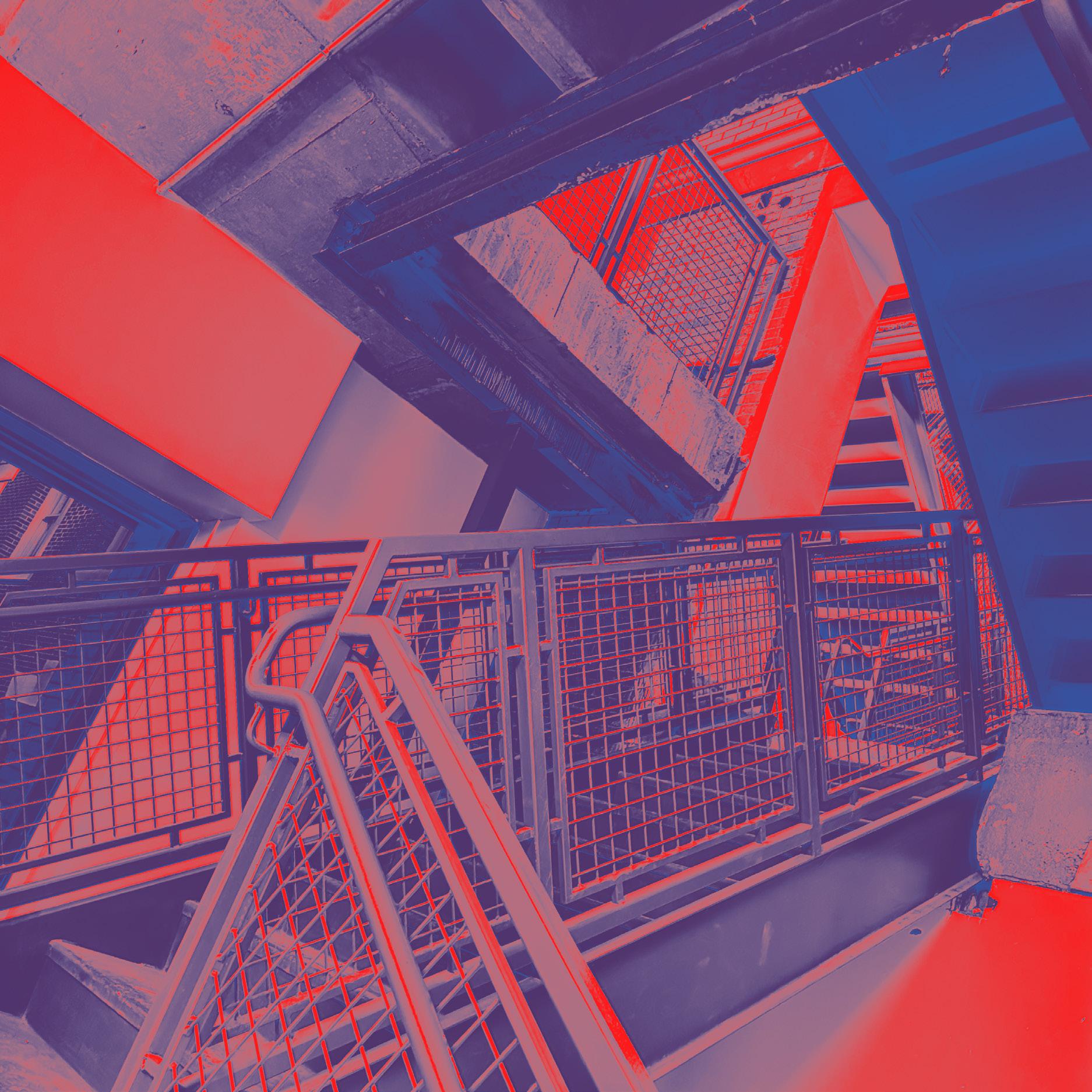

Stairwell Between

“Part I: Spiralling”

Hidden inside Slocum’s School of Architecture, where weary-eyed students pay to rush deadlines, stairs many walked up to Studio just as we do, the bustling occupants sweating pure epinephrine, there is a space unlike others. Maybe I was sleep deprived (I am), but amid a call on hold, I walked out of the secondfloor studio and sat on the stairwell nearby —those stairs that join Link Hall, the School of Engineering to Slocum’s School of Architecture. Stairwell 2 is a literal manifestation of the tacit connection we have with the engineering students. Maybe it’s the tired eyes, but these walls don’t seem to align. Nothing makes sense here. The ceilings pull far up and immediately push down. Partition walls try, as they might, to block the light scattering from the large glass pane. The floors just don’t meet at all to Slocum’s own ground. Gray stairs extend left and out. You have to go down to go up. Standing in one spot, the adjacent floor meets you at eye level. Have I finally done it? Was that too many Celsius in one day? In many countries, death is in progress. We, all living organisms, and energy live in a cycle of samsara. We are born, die, and are reborn. A loop that keeps going and going. If you could remember the lives you lived and the lives you could live… maybe it would be better not to. If we live in a perpetual cycle of insanity, is this the space between? The null, the void, the between. Sitting on the dusty grey floor, I don’t remember entering at all. Looking around, stairs talk over each other, from wall to wall, sporadic turns after turns, floors have no numbers, nor should they be numbered. Connecting to each crevice of Slocum, my gaze tilts up to the plastic sign “Floor 3”. Every door is a door to the lives that could have been lived.

Souls I could meet murmuring from behind each closed door, creaking open ever so slightly in the breeze. Gazing down, there were doors to the lives I had lived spelled in “DANGER KEEP OUT”. One by one, the lattice grid above me barricades places I could be. Cracks in the walls, cold air blowing on my sides through slits of plasters. Mechanical systems, HVAC cooling, pipes, I-beams, and bolts hang precariously. It’s as if ; the stairwell itself appears not meant for habitation, like people were never supposed to be here, like I shouldn’t be here. Maybe that’s why no one ever stays. Construction workers walk up and down. Students pass without a second glance. Cracks and crevices, objects from a century ago, exist undisturbed. The old Slocum entablature breathes asthmatic whilst a 6-foot stair jabs across its front visage. Walking down those same steps, each stride accompanied by gasping for air, the broken entablature whispers to me.

“You barely noticed this stairwell standing outside - with all the cold air rushing you, how could you? The ridiculous facade where Link and Slocum join certainly doesn’t help. How could the stairwell be seen?”

Yet, from inside, everything is clear. Every step, all the time you carried museum boards from Schine, you never even noticed you were being watched. An invisible space that never was meant to be, born from pure contingency.

“Part II: Ruminating”

Certainly, this isn’t the only strange space that excited passersby. Many nooks and crevices exist in the landscape of architecture. Residual spaces left behind as we continuously expand the empire. The strangeness and byproduct of progress leave these zones

unfamiliar yet familiar. The Catalonian philosopher Ignasi de Sol-Morales, in his essay, envelopes the concept into a word: “Terrain Vague.” The author describes Terrain Vagues as abandoned, uninhabited, residual spaces, left for vegetation to regain as materials decay slowly.

“The Romantic imagination, which still survives in our contemporary sensibility, feeds on memories and expectations. Strangers in our own land, strangers in our city, we inhabitants of the metropolis feel the spaces not dominated by architecture as reflections of our own insecurity, of our vague wanderings through limitless spaces that, in our position external to the urban system, to power, to activity, constitute both a physical expression of our fear and insecurity and our expectation of the other, the alternative, the utopian, the future.” 1

The power of these overlooked areas lies in their lack of authoritative control. No single program has dictated the space, no one truly holds ownership. The potential and unbounded identity pokes at uncertainty, both fearful and hopeful. Terrain

1 Ignasi de Sol-Morales, “Terrain Vague,” in Anyplace, ed. Cynthia C. Davidson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 120.

Vague often laughs at capitalism as a mindless rapid expansion with careless oversights. Neglected spaces hold limitless potential. Ignasi de Sol-Morales doesn’t outright reject urban redevelopment of the area but encourages a sensitive approach, one that embodies the uncertain and open-ended qualities.

The Fremont Troll project, for one, was an artist community that transforms the leftover space of an underpass through an installation of a too-well-known Scandinavian icon. From somewhere drugs were injected into veins to the vibrant blood of the neighborhood, the troll sculpture continued the expression of ambiguity and mysticism but drew a touristy crowd.2 On the other hand, a poor example of the Terrain Vague may be the Highline in NYC. The project in itself was highly successful as a green development. However, it completely sanitized the obscure and vague potential, transforming the railway into a capitalistic venture that dominoed the gentrification of surrounding sights. Although a less extreme example of Terrain Vague, Stairwell 2 and its sister construction are an afterthought that retain a mystic quality, one that is isolating and contemplative. In the broader conversation, the stairwells hint at Michel Foucault’s Theory of Heterotopia, the in-between space of utopia and dystopia, othered and strange places that disobey human norms by layering meanings after meanings. Although heterotopias are spaces constructed and Terrain Vague spaces deconstructed, both mirror society. The two terms have a shared quality.

“The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible.” 3

One such heterotopic space is a museum. An othered place where time and space accumulate, artifacts from all corners of the continents and time collapse into a singular point. Not just Museums, but theaters, Persian gardens, cemeteries, and zoos are all juxtapositions of the world. Theaters, through a collage

2 Daniel Winterbottom, “Residual Space Re-evaluated,” Places 13, no. 3 (2000): 48–53, https://placesjournal.org/article/residual-space-re-evaluated/. 3 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” Architecture / Mouvement / Continuité, no. 5 (1984): 6.

of actors and sets, bring unreachable space and periods to the audience. Persian gardens and their four parts are symbolic of the world. The cemeteries accrued bodies from all ages and places. Zoos trap fauna that wouldn’t normally exist in a particular location. As well, the stairwell collecting century-old dust speaks of a time long past, now meeting the contemporary pipes and beams. Not only does the stairwell juxtapose space, but also reflects the insanity and artificiality of everyday life. The disorganized chaos of elements and history contrasting places outside is an illusionary heterotopic reality. If societal norms dictate the way we should act in certain places, I find this stairwell and its inability to reconcile with society as messy as freedom.

“Part III Releasing”

The Salk Institute plaza’s travertine floor parted softly with the thin flowing stream towards the horizon is a void space leftover from the two buildings. Louis Khan’s residual space creates a musing, contemplative transition, arguably the highlight of the architecture. The void isn’t made because it is empty itself but because it’s between the two towers.4 I’m often drawn to these strange spaces because, just like everything in my identity, I’m always in the middle. Often, when Slocum is mapped like an assembly line, there is solace in the stairwell. There is a soft atmosphere. A soothing space where one can hide from all the pretension, all the hustle and bustle, all the eyes staring at me, all the competition, all the anger, and all the fear distilled in my blood. Going up and down, left and right in this maze, I realize I’m not the only one lured to the stairwell’s whisper. Two stools conversing next to the aperture. Foil of chips and sweet wrappers scurrying along the floor. Cushions hiding behind stairs. Guitars, larynx, and cajon lost in symphony. Voices murmuring at the old man’s split face entablature. If life is a cycle of action and inaction, construction and deconstruction, birth and extinction repetitively mad, there is a quiet sanctuary in the fleeting gaps of the space between.

4 ArchDaily, “AD Classics: Salk Institute / Louis Kahn,” last modified March 22, 2010, https://www.archdaily.com/61288/ad-classics-salk-institute-louis-kahn.

Destroying Space: Core Aesthetics

Rabi Qiu, ‘29 Architecture Student

Most of us, while scrolling over the internet, would at some point encounter one of these odd images, typically featuring the snapshot of a place that triggers an uncanny sensation. Strangely, these pictures do not create uncanniness by horrific elements. The architectural elements and objects often appear normal and insignificant, except for some dissonance in the way they combine. Moreover, rather than being forwardly scary, these spaces come across as disconcerting yet nostalgic or even soothing on occasions. Netizens refer to these arts as the “core aesthetics,” such as Weird Core, Dream Core, and Urban Core. Many of these core arts rely on the use of space to achieve the effects. In these eerie environments, space is deliberately distorted, and the normal spatial experience is destroyed to create an unsettling, surreal feeling that one would not experience in day-to-day life. These internet aesthetics, especially Dream Core, are partly a continuation of the 20th century surrealism, which shares many commonalities in concepts and executions. Surrealism emerged as a reflection of its time; it uses symbolic languages and irrational expressions to evoke reflections on society, politics, and culture. Surrealistic arts similarly distort our perception of familiar objects and settings by either twisting their features or misrepresenting them in a manner that we

do not see in real life. Cores, as its modern parallel, inherit many of these characteristics. The connection of these two art movements provides insights into, beyond arts, reflection of space and society they dwell upon. A common association regarding the creation of this strangeness is the concept of liminal space.1 While liminality does work as a frequent component, it is far from being the whole story. The key to the unique experience of these spatial compositions is the distortion of the familiar, and liminality is merely one of the integrals. Looking at these distorted spaces triggers discomfort because the brain is alerting that something is wrong and trying to stir up an instinctual response. Even though this response to things being weird is a survival instinct that has existed for millions of years, the element that triggers

1 Liminality/liminal space: Liminality describes a transitional stage, in which the past phase is still lingering and the phase ahead is yet to come. The transition can be both spiritual, such as going from high school to college, or physical, such as going from the garden to the living room. Liminal space is the space when this moment of transition is prolonged and becomes a state of existence on its own; people described the experience as being trapped between two worlds and being neither-nor. Arts sorely built on liminal space (which is often directly titled “liminal space” largely falls into the parachute term “core” but has certain unique qualities compared to other subcategories with the suffix “core.” It is however not the focus of this article.

the alarm—which in this case is the subtle oddity in spatial composition—is not that old. Nevertheless, these distortions of space universally trigger a subconscious feeling of uneasiness, almost as if they are something humans shared deep inside. Could this be a feature from the collective unconscious of modern humans? If so, how was it formed?

I took a closer look at these “cores” and found out that although formed by different elements, they mostly share a commonality: dissatisfaction. There is dissatisfaction from personal to cosmopolitan scale: trauma, regrets, alienation, society… Under this premise, the spaces are means to question and quietly rebel against their reality—very much like their 20th century precedent. As a form of art, the uniqueness of these “cores,” as opposed to ordinary internet venting, is that rather than plain negativities, they are faintly reaching towards an alternative reality, one where physical and mental autonomy has space to stretch. They are a means to escape: distressed by reality, people turned towards this conceptual destruction for expression and for comfort; they made spaces where things do not have to make sense—in contrast to the stressful reality, where things are forced to be in a certain way and where people have little control over their present and regret for the past. This is a means to temporarily release oneself from the modern environment and its way-too-recognized routines. It silently challenges the existing conditions by twisting its associated features and invoking reflection on their rationality. The spaces are weird because they do not comply with the norms of the world with which we are familiar: staircases that lead into walls; long corridors without windows; grass grows inside the room; furniture placed in awkward positions;

empty public spaces, such as shopping malls, which should be busy. The spatial dissonance links to a feeling of “incorrectness,” as only a fragment of all possibilities is defined as “correct” or “normal.” Our world operates under an artificial rule set that, implicitly or explicitly, demands things to be in a certain way. Very much like social norms, there are uniform, underlying rules on how spaces should be that people have absorbed and called “normal.” When the space needs to promote efficiency, methods that increase space utilization, lower moving distance of mostly used routes, and maximizing the user’s speed in getting things done are the major controls. These straight path solutions lead to spaces that are highly monotonous and rigorous in their logics, as we see in many office and commercial buildings. While configurations vary, their nature remains unchanged. Under the frame, the range of spaces that are “correct” to create is fairly narrow. Modern spaces of all kinds have evolved to be highly efficient, comfortable, and scientific--things “core spaces” are now challenging. Of course, space must admit the validity of rules—comfort, safety, harmony, efficiency, materiality, and more—to function properly, which is why architects must go through rigorous training. Not that the prevalent point-to-point method in commercialized spaces is invalid; quite the opposite, it is too logical, especially under a framework that is questionable by itself. The point is not to design internetaesthetic-based quirky spaces—many of them are not inhabitable or simply do not make physical sense. “Core” are not solutions but inspirations; they lead us to rethink what space should and can be. If people are destroying space to seek shelter, should this rise some reflection on the out concept of “good” space and the systems of thought they are built upon?

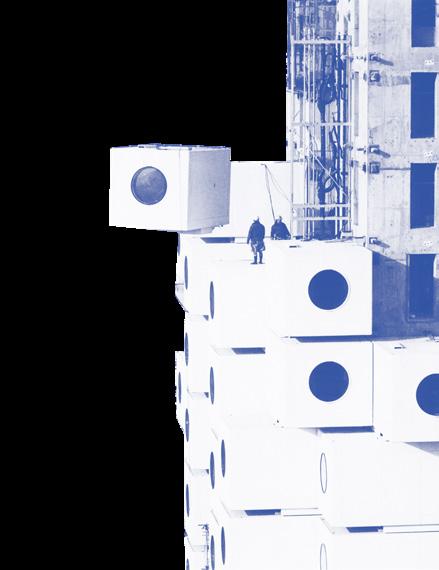

Architecture’s Life Cycle: Birth, Death, and Rebirth in Metabolism

Isabela Santana, ‘29 Architecture Student

The life cycle in which architecture undergoes, is parallel to the one in which humans have seen for centuries. Life begins at birth for humans, and ends in death. When examining architecture, this cycle is no different. A proposal is made, creating “life”, and when destruction occurs, death triumphs. Metabolism, a type of architectural movement, has roots in the phenomena that architecture can equate to life. Not in the sense that architecture is metaphorically life, but rather, architecture holds the power to revive and bring life into something as large as a city, and down to something small like a person’s life. When life is given in the form of architecture, it changes and adapts to thrive, but can sometimes fail and become destroyed when its structure can no longer sustain itself.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa (Figure 1), for example, resonates heavily with the idea of life, death, and rebirth within architecture. For Kurokawa, the building of the capsules had innuendos to life. Through clever design choices, he regards the lifespan of a capsule as, “not a mechanical one, but rather a social one, implying that changing human needs and social relationships would necessitate such periodic replacement.”1 As how a human body changes and evolves as it ages, Kurokawa anticipated that the Nakagin Capsule Tower would do the same. This phenomenology between the human experience and architecture deepens the meaning of what it means to bring life into architecture. By regarding the Nakagin Capsule Tower as a system that has a life and body, rather than a machine, it allows for a more personal connection between the space in which people inhabit.

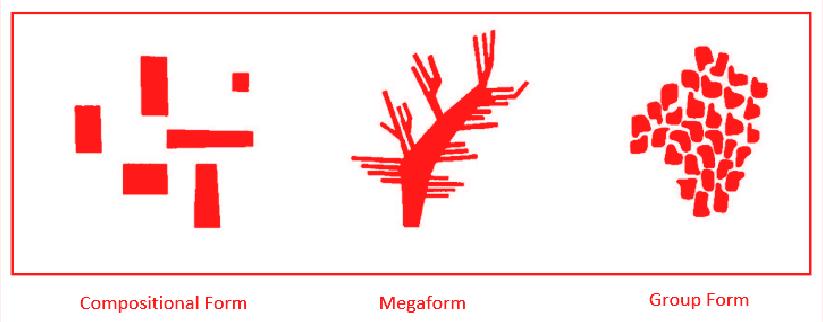

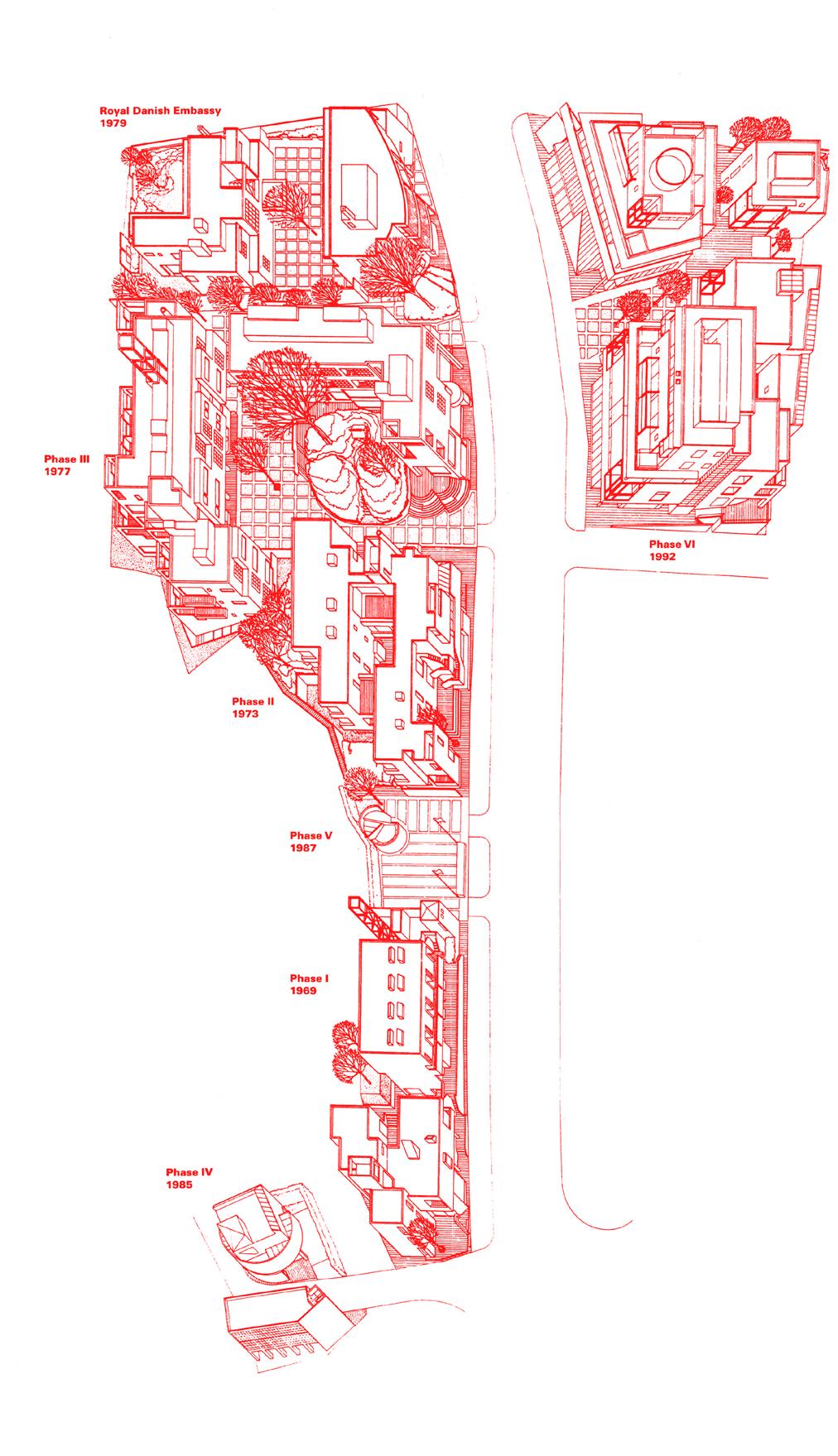

Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, also recognized for his metabolism approaches to architecture, had opposing views to Kurokawa. In his book, Investigations In Collective Form, he argues that modern

1 Lin, Zhongjie. “Nakagin Capsule Tower Revisiting the Future of the Recent Past.” 2011, Accessed 2024.

cities are chaotic and visually unappealing, leaning too much into the concept of being flexible and temporary when they should become organized and permanent.2 Maki created his own design form in retaliation entitled “Collective Form” which consists of three sub categories for designing future urban spaces: compositional form, megaform, and group form (Figure 2). Through this collective form of design, he theorized that future building practices in urban settings would begin to grow as time went on, culminating into something larger and more impactful than the simple top-down approach. One of Maki’s most successful projects, the Hillside Terrace (Figure 3), utilizes group form in order to accommodate a mixed space used for living, socializing, and commercializing. Though Maki’s practice is distinct to those of Kurokawa, there is an underlying similarity between both projects—the notion of rebirth. In the case of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, the building was destroyed in 2022, but rebirthed through saving twenty three capsules and repurposing them for further residential use. The Hillside Terrace continues to thrive and continue its cycle of life through newer additions, never remaining static but always in continuous motion and growth. As humans have to adapt to the challenges life brings, buildings and cities also need to adapt to destruction, chaos, and change. The design impacts of Kurokawa and Maki have continued to influence the way in which architects build for the needs of urban spaces, allowing for more future forward designs and emphasis on the building being an organism—not just a solid volume.

Diagnosis and Healing of the Postwar Wasteland

Yitang Zhang, ‘28 Architecture Student

“Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?”

- The Grimm Brothers’ Fairy Tales.1

After the guns of the World Wars had fallen silent, Sigmund Freud’s consulting room deliberately placed a mirror directly opposite the window. When the patient sat down, he was forced to face his reflection head-on, representing the patient’s externalized self. This spatial layout metaphorically represents the essence of therapy: the individual’s confrontation with oneself. The analyst sat in the middle, becoming the mediator who guided the patient to dissect himself. Here, the mirror simultaneously serves as a symbol of diagnosis and healing. Freud was more sensitive than anyone else of his time to the psychological upheavals caused by the war. He was acutely aware of the fundamental and irreconcilable tension between human instinctual desires and civilization’s moral, legal, and social norms.

1 Brothers Grimm, The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales (Pantheon, 2011)

2 This internal tension had been eased in the pre-war era by religious faith, a vision of the future, and an optimistic spirit, but the war destroyed culture and belief, and people’s previous trust in power—whether political or religious—transformed into widespread dissatisfaction, culminating in hostility towards architecture. Why would dissatisfaction with power connect with architecture? Michel Foucault pointed out in Discipline and Punish that architecture is not a neutral physical space but a medium through which power is most directly implemented.3 For example, the spatial layouts of prisons, hospitals, and schools imply a profound logic of discipline, in which bodies and behaviors are strictly monitored and shaped within these structures. Each individual within architectural spaces is subject to control. Architecture is stable, orderly, and solid; thus,

2 Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and Its Discontents. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 1930.

3 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1975).

architecture becomes the most immediate intermediary of manipulation between power and individuals. The gunfire of war and the rapid expansion of industrial technology have infected architecture with illness. Unprecedented doubt has made us unable to trust the stability and eternity that architecture once claimed. The architecture and authority once regarded as absolute truths have all shattered into fleeting and illusory dreams in the face of the violence of war.

However, the city’s destruction was accompanied by enthusiasm for reconstruction and regeneration. In post-war Paris, people became obsessed with the spacious and bright streets of upper-class residential areas. At the same time, in the old city, spaces following medieval patterns remained dark, damp, decayed, and crowded, lacking sufficient ventilation and drainage systems. Working-class families were compressed into cramped attics and back alleys. Architecture thus became both a symptom and the only means of self-healing, becoming a mirror called “modern.” As Mumford said, people at one with the world need no mirror. Still, in an era of psychological regression and cultural disintegration, people must hold up a mirror to examine themselves.4 Le Corbusier keenly perceived this necessity, starting to reflect and heal the wounds of the times through architecture.

Mirrors are permeable.

In most pre-modern or traditional architecture, the unmistakable sense of boundaries creates a sense of physical security and order, with walls, roofs, doors, and windows demarcating a stable social order and a space for memory. Solid boundaries typically correspond to stable traditions, identities, and memories of traditional society. However, modern architecture has broken this clarity.

4

Deleuze’s classic image of a person facing two parallel mirrors vividly expresses the infinity of mirrored space. In Paris, people trapped in narrow alleys longed for breath and openness, precisely the traditional city conditions that Le Corbusier deeply resented. Through techniques such as the spiral staircase and continuous ramps of the Villa Savoye, he continuously extended and expanded the space, allowing people to experience the infinity of space beyond physical boundaries, achieving a psychological therapeutic effect akin to mirrors.5

Mirrors are Hallucinatory.

In “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” Georg Simmel pointed out that urbanites have developed a “blasé attitude” (an attitude of indifference) in the face of excessive stimulation, which is a mechanism of escape and self-protection from the overload of urban cultural symbols.6 This reveals the reality of people’s boredom with the explosive proliferation of cultural symbols. In the mirror-like modern space, people experience detachment from reality and mental emptiness. The infinite nature of mirror-like architecture forces people to repeatedly re-orient themselves in a space that is unclear where it begins or leads. As Mumford said, in a fragmented reality, people must constantly use mirrors to relieve anxiety, reaffirming their subjectivity.7 Alternatively, they confirm their objectified self-image and identify with their reflected self.

Mirrors are sublime.

When Le Corbusier revisited the Acropolis in 1933, he described its architectural space as transcendent.8 The experience created by this space approached Edmund Burke’s definition of the sublime,9

5 Anthony Vidler, Warped Space : Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture (Cambridge, Mass. ; London: MIT, 2002).

6 Georg Simmel, The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903; repr., Rome: Europaconcorsi, 2017).

7 Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1934).

8 Le Corbusier, Journey to the East (MIT Press (MA), 1987).

9 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (Scholar Select, 1757).

for he felt violence and oppression from the Parthenon, a feeling that directly produced the sublime. This sharply contrasted with the Parisian slums he considered ditches.

Modernist architecture significantly weakened preexisting “decorative meanings.” Here, architecture is like a vast, smooth mirror where all external cultural textures are erased. The purity and abstraction of space imbue architecture with a certain violent power—direct, intense, uncompromising.

Mirrors are revealing.

In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas suggests that the vertical collage and functional juxtaposition of Manhattan’s skyscrapers reflect a radical urban logic: the infinite expansion of human desires and ambitions. Each floor is like a fragment of the city’s subconscious, separated yet collectively forming a surreal whole.10 This practice is not absurd or random on the surface but profoundly reveals the essential nature of the modern city as a projection field of the collective unconscious.

Koolhaas further argued that architecture should actively correspond with the city’s unconscious. As Freud said, the subconscious is not evil or chaotic but an authentic reflection of human internal trauma and desire. Architecture thus subconsciously resonates with human psychology, offering a therapeutic response—an absurd yet precisely effective remedy for an absurd reality.

Just as mirrors reveal inner truths, this deep dialogue exposes urban trauma to the daylight, becoming the starting point for healing. The city and its architecture no longer suppress desire but become sites for releasing and reconstructing it. Thus, we understand architecture’s more profound significance—a collective therapy of confronting truth and accepting oneself. Humanity can finally reconcile with itself through countless gazes and introspections, and the city’s wounds will ultimately become the source of creativity.

Interview with Hermine Demaël

Anita Yasinska, ‘29 Architecture Student

This interview was conducted by Anita Yasinska, a 1st year Architecture Student, in conversation with Hermine Demaël, a professor at the Syracuse University School of Architecture. Within this interview, Demael discusses her stance on architecture as both destruction and renewal—exploring borders, housing, and the shifting role of the architect through teaching, research, and design.

Hermine Demaël is an architectural designer and researcher. Her work investigates the political ecology of building practices and the role of architecture in our transitioning energy landscape.

The theme for this issue is destruction as architecture. Architecture has a long history of destruction and reformation. Destruction can also act as a positive metamorphosis—to destroy is to decide what is of value, and in that lies like an inherently controversial act. So it’s very much up to interpretation of people’s view.

I saw one of your projects, it was called peekaboo. It was for the 26 international garden festival. And it was where you rethink the notion of border in today’s post-colonial context. I thought that was

very intriguing because I feel like you could tie in some aspects of our theme into that.

In the future, how do you think destruction and reformation is important in advancing architecture and the role of architecture in society?

I’d say my work right now is maybe a form of destruction of what is the role of the architect. I feel like my interests are very fragmented right now, and that’s a result of where I went to school, where I’m interested in going. A big part of what I do is teach, obviously, then I do research that’s pretty signed, maybe more like a scientific approach .I’ve been working for many years at retrofitting existing social housing stock.

And then what I also do and that’s maybe the funniest part is design, mostly with Steven Zimmer, who also teaches in the school, and that’s the garden competition that you were talking about. We’re breaking ground soon, so that’s exciting. We were responding to a theme about borders, which was an open call and how we approached it is more through the sense of disrupting what landscape architects want from a garden but also provoking architects by bringing in more landscape strategies.

Is there anything that surprised you and what’s your approach to teaching? You were teaching mostly people introduced to architecture rather than teaching at a graduate level.

Yeah, I think it’s really a challenging thing, when you’ve been designing for a while, to remember how to talk about architecture to people that don’t know yet. I do quite a bit of that in some of my research work, like with those people working in social housing. A lot of the stakeholders I interact with don’t really have the architect lingo. So I’ve been used to being a type of stakeholder. But working with young students that want to be architects, honestly, is also about positioning myself as an instructor. I think there are things that I learned in school that I don’t want to teach you guys. The first year of teaching is about recalibrating how I learned and how I think you guys should learn, because it’s been like a decade. So, things like different priorities, different scholarships have happened. So, there’s some shift.

What

inspired

you to become a professor?

It’s a number of things. I think mostly right now, it’s the flexibility that it allows us to find time to do other things. I’m still pretty early on in my career and I don’t want to just go down the practice path or just go down the purely research path. So I think teaching is a nice way of balancing both. I think what my peers often talk about is: do you teach to practice or do you practice to teach? They are two different positions in the field and are represented equally in the building.

What inspired me to teach? I think a number of mentors particularly in grad school really suggested that I go down that line. I feel like schools are more exciting environments than offices. You’re more aware of what the trending topics are. You’re more challenged by your peers, you’re challenged by students. I like the discourse and the dialogue that that allows.

What do you hope to get out of teaching—any future goals?

Become a better teacher first. Work on understanding how you can teach architecture well, given the crisis the profession is going through, or if it’s about destruction, the different things that are going on, how do you still make architecture relevant and how it can be applied differently. So thinking through that with students, I also think architecture education, even if you don’t want to be an architect, is a really, really good program or major to go through. In many ways I think it’s the best education. There’s all the social sciences, the history, the theory, and you become super aware of how the built environment is designed. So I want to get better at that and then down the line building good housing. Ultimately I just want to focus on the housing models.

And moving forward, you mentioned the crisis in architecture. Can you just go a little bit deeper into that?

Everyone always says architecture is in crisis, but architecture has been in crisis for centuries.

Due to technology?

Nothing really has changed. It’s still a service industry, you still have your clients and still are subject to the pressures of the market. So it can get really hard to do work, get work or do good work. I think there’s just a lot of conflicting things. Technology is disrupting some of the roles that we’ve historically had. Some climate problems are really forcing us to reevaluate how we build. Some people are not really willing to reevaluate, but they’ll have to. So that’s one thing. I think historically, the profession of the architect is enabling a certain form of power. Obviously as a service industry, you have clients and you’re putting things out there on behalf of the client. That’s something that people are grappling with.

Everyone will have an answer as to why architecture is dying–but also why it’s then so relevant.

A lot of people will say architects can’t do anything anymore. It’s all developers or AI, and people, depending on what they care about, find something like this crisis in different discourse.

So what made you pursue architecture?

Maybe I have to ask you that question. I feel like I wasn’t really sure. I just went into it with a loose interest. I honestly have no answer to that whenever people ask me.

Why are you in architectural school?

I took architecture courses in high school and I was always around my dad when he would go to sites since he works in construction. I am interested in the philosophy of it, why people have the need to build and toward what future? I’m very interested in post-war Architecture. It’s very important because with our theme surrounding destruction, I feel like architecture can both act as destruction, but also act as a replenishment.

I think destruction is a nice theme. As you said in your introduction, things fall apart, things crumble, and it can be an exciting time to rebuild. So, finding a fine line between rebuilding from scratch.

But now, I don’t know why I walked in, I know I have many reasons to stay. It was a journey. It’s a journey that never ends for sure.

Do you have any particular pursuits in architecture that you’re interested in? Because architecture is so diverse; it’s not just about designing. There could be a political side of it. There could be the theory side of it. There’s so many different pursuits

within architecture.

Right now, because of the work that I’m doing, I’m really obsessed with gardens, atmospheres, histories of this and how that has impacted architecture and this loosely. I think also down the line, I just want better housing and so that really is my goal. We’re going to be living differently, probably more collectively, with plants, with people, with different types of conditions that we haven’t, maybe in some parts of the world we haven’t experienced yet. Also thinking about what aesthetics that is going to produce. That’s something I’m working on, or excited about.

I think what I’m interested in is making sure that my design work remains fun. There’s the tendency, especially in schools, to really be so serious about everything. I think at times it’s good to have restraints. It’s very good to understand the histories of things, and be careful, be attentive to context and so on. But it’s important as designers that we keep finding what we do fun and entertaining. It should be fun. And that’s also what I hope my students retain. Some parts are really hard and some parts are really annoying, but ultimately, you should find it fun because you can only really sell an idea that you like or believe in. if it’s not a labor of love, don’t do it.

And then one last question. I just wanted to ask if you have any remarks, because we also care about how architecture students are doing, so I know that there’s students that go through things like mental health, obstacles and also, just roadblocks. So, any advice or wisdom that you would give to architecture students?

When they feel defeated?

Yes.

It’s hard. It relates to my point about trying to keep it silly

and fun. It is a really hard profession and the thing that I would love to remind students is, it doesn’t get easier and maybe that’s not fun to hear when you’re a first year and you’re already finding it hard. Some parts get easier, like, drawing convention, you get better at it. But you kind of always live with the struggle and the doubt. Learning to love parts of it, as early as possible; learn as much as you can from your professor, but it really is not about if your professor loves your project or not. And I know that’s very hard to get to that level of confidence in your own work, but that’s what you should be striving for.

Is the morale feeling a bit destructed? Is that what’s going on? Is it a first year thing or is it something that you hear from upper years?

I feel like all around, it’s so easy to feel defeated in this profession. It’s very difficult. I feel it’s easier to feel defeated than to feel like you’re doing it right.

That, unfortunately, I will say will last forever. But, you need to define your own metrics for what you think. Learn as much as you can from each method. What’s really awesome in the school is you get 10 semesters, you’re going to be exposed to 10 different methods of doing things. You will never fully love all ten of them or even one entirely. But learn from some methods from professor one, then from professor two. I say get sleep, as what everyone is going to say, eat well. Architecture can do a lot, but architecture is really not everything. Whenever you think it’s the end of the world in this building, go to another department. Go learn from the people in visual arts. Talk to the structural engineers, talk to people in other departments, because I think putting things into perspective is helpful and you can only really become a good architect if you have outside interests. That’s my main suggestion. Go to the lectures, but also the lectures in different departments. Read books, watch movies. That is my advice.

Urban Food Production System

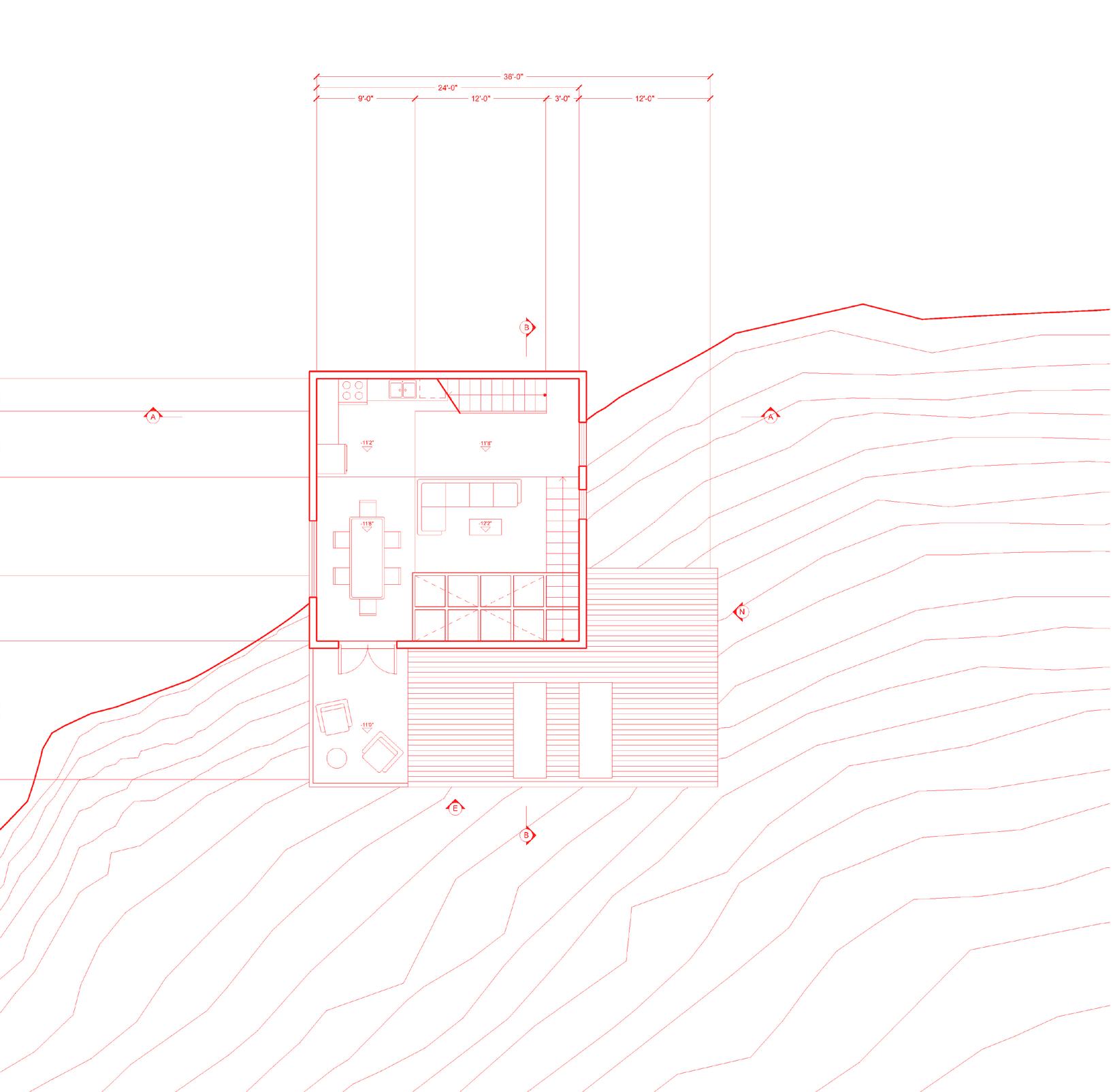

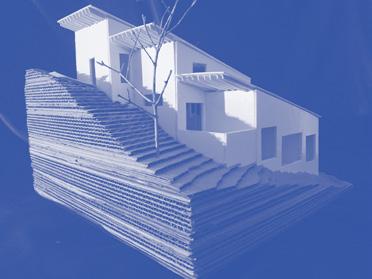

A Dwelling for a Man and His Daughter

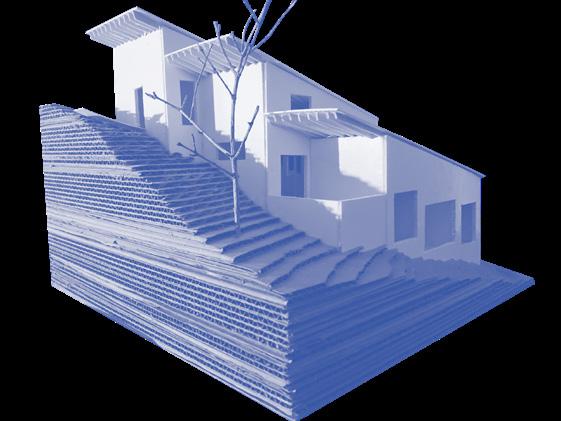

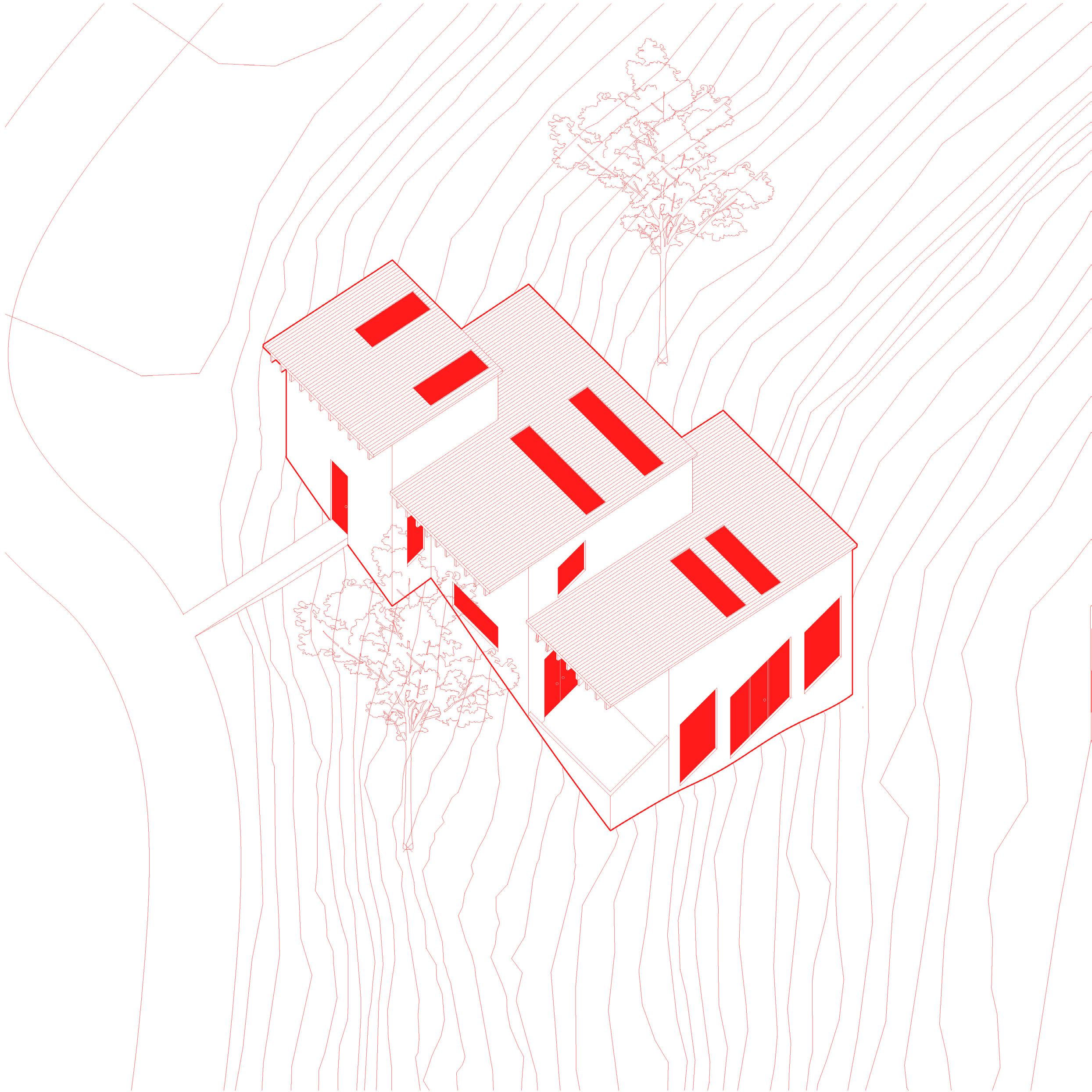

Samuel Pisoncik, ‘29 Architecture Student

Last semester in ARC 107, our studio class was tasked with creating a dwelling inspired by spatial logics of a precedent house. From my precedent, the CIEN House, I utilized ideas like a processionary circulation path to develop the design for a dwelling for a man and his daughter situated diagonally on a hill. Throughout the semester I put in place a rational, logical based approach to my design where all design moves fit together like puzzle pieces. The puzzle piece of aperture placement was connected to the puzzle piece of views which is connected to the puzzle piece of the procession, which in turn is connected to the puzzle piece of the hill. Architecture is like a puzzle, there are a vast amount of different systems and puzzle pieces and apertures that need to be integrated together into one cohesive system that makes sense. This semester however, I have become more aware of emotionbased architecture. It’s an architecture that has more spontaneous material, lighting, or sectional-based moments. Although it still forms what seems to be a puzzle, that puzzle is more fluid, and almost dissolves in certain places. The logical puzzle has a strong material quality while the fluid one contains a presence that can’t really be dissected. Although the two types seem to be disparate, they both are critical for creating truly amazing architecture. An architecture that is financially, structurally, spatially, and sustainably feasible, yet still has special moments that make it unique.

DESTRUCTION

NEW TO OLD TO NEW R B U I L D I G E U S E U T F L D

Module believes in the power of print publications. The printing of this publication involved 34 pages in 8 sheets, printed by risograph using 35 masters and 2100 impressions on Mohawk Superfine Paper, with 60 copies printed, trimmed, and hand-bound by members of Module Magazine.

The opinions articulated in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views or policies of Module Magazine’s sponsors.

Back cover image: Toby Pang