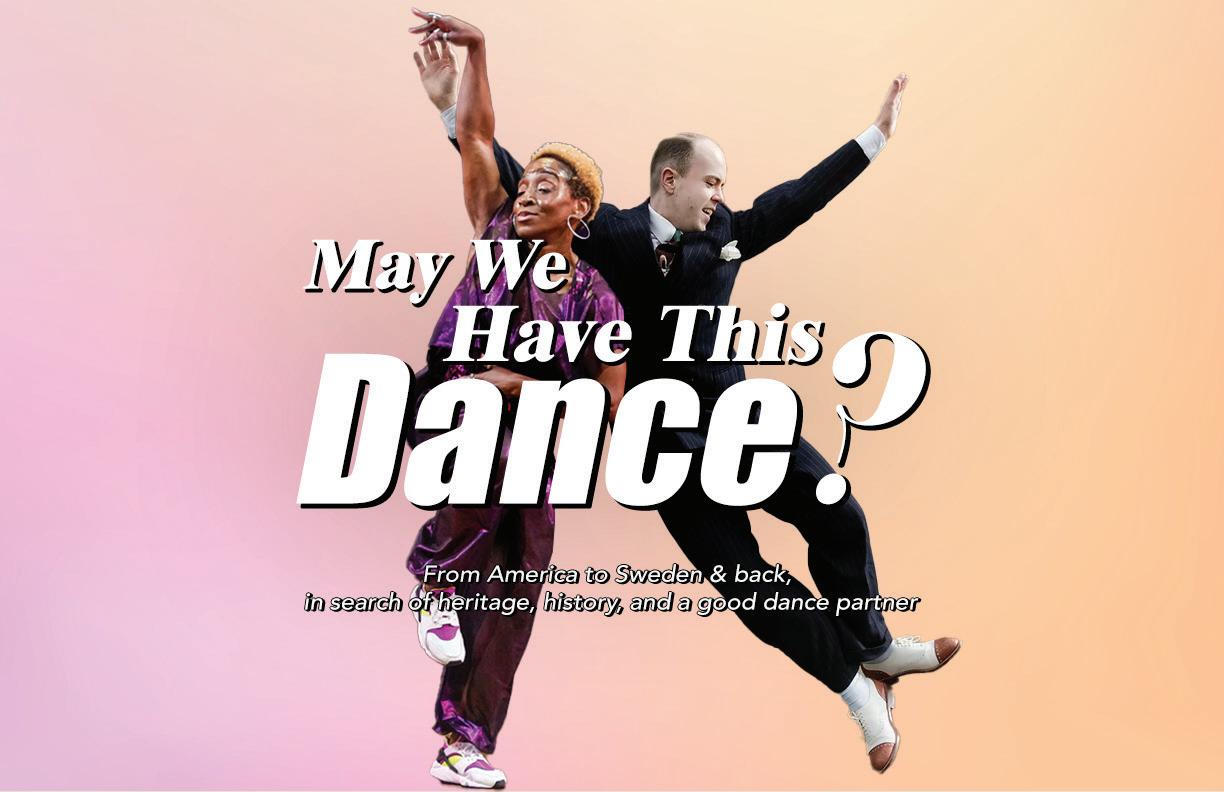

Main Characters

LaTasha Barnes is a critically-acclaimed dance artist, choreographer, educator, and tradition-bearer of Black American Social Dance. She is globally celebrated for her musicality, athleticism, and joyful presence throughout the traditions she bears: House, Hip-Hop, Jazz, and Lindy Hop, among them.

Felix Berghäll is a choreographer, performer, educator, and DJ in Lindy Hop and African American Vernacular Jazz. He has been part of the Swedish national team as an athlete in Boogie Woogie and Lindy Hop and is now Co-Head Coach with his partner Mikaela Hellsten.

Marie N’diaye is a Lindy Hop and African American Jazz dance choreographer, performer and educator. She fell in love with Lindy Hop in 2006. She also leads Collective Voices for Change, a nonprofit created as a platform to address social issues in the Jazz dance community.

Frank Manning was an American dancer, instructor, and choreographer. He is considered one of the founders of Lindy Hop. He was a member of the Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. He choreographed the spectacular Lindy Hop sequence in the 1941 movie “Hellzapoppin’.” He also co-choreographed the Broadway musical Black and Blue, for which he received a 1989 Tony Award.

Other Characters

LaTasha’s Great-Grandmother

Herräng Dance Camp President

Barack Obama

Chorus

Herräng Lindy Hoppers

Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers

LaTasha

Synopsis

On Easter Sunday when LaTasha Barnes was four, she saw her great-grandmother dancing with a friend. LaTasha started dancing too.

“I ran past her and I jumped and she kind of lifted me a little bit higher. This is how we danced growing up. We called it fast dancing.”

LaTasha wasn’t taught swing dancing in elementary school. Her family didn’t want her to pursue dance professionally, so she joined the military out of high school, and by her late twenties she was a telecommunications specialist for the Obama administration. LaTasha continue to dance on the side, winning the World Championship in house dance in Paris in 2011. That same year, her greatgrandmother passed away. LaTasha was in her 30s, and wanted to know more about her great grandma’s dancing, to reconnect to her heritage.

“I realized that I’d had an elder I hadn’t gleaned enough from. There was some understanding missing; I did not have that personal relationship with jazz.”

She found out pretty quickly that the acknowledged center of Lindy hop had become Herräng, Sweden, a tiny town of several hundred. Every summer it hosts thousands of Lindy Hoppers from all over the world, including Norma Miller, Sugar Sullivan and Chester Whitmore, some of the original dancers. In 2016, at thirty six, LaTasha won a scholarship to study Lindy Hop in Herräng.

Growing up in a small Swedish town called Axvall, Felix Berghall never quite felt like he fit in. In a culture about not standing out, Felix was emotional — an oversharer. When he was eight he discovered swing dancing in PE class. He started going to dance lessons, meeting new friends, and soon he was performing at local events.

“I do remember very vividly that I felt accepted for being that person that was loud and expressive and so, like, you know, very outgoing.” Felix

In 2004, at twelve years old, Felix attended his first national dance championship. He saw a couple dance to Julia Lee’s “Snatch and Grab It”.

“They were hitting everything in the music! I thought, how can they do it? How can they understand each other?”

Felix was hooked. He started to compete more, and by the time he was 21, Felix had snagged a spot on the national team. In 2009 Felix began working at Herräng as a staff instructor. In 2013 he went to the International Lindy Hop Championships in Washington, D.C., where he and his partner won first place in their division.

Herräng

When LaTasha got to Herräng in the summer of 2016, she loaded up her schedule with workshops. She had come to Herräng to study historical footage with teachers that could break down the mechanics of Lindy Hop. There was good footage, but some nights there were clips that LaTasha was not comfortable with.

“ I remember one being called ‘The Beauty of Southern life’. I was like, I know you lying. In the 1840s, the beauty of Southern life for Black people? OK. All right. Cool.”

Felix was asked to be part of a panel with two Black dancers from the U.S.

“I said that if I could, I will go back to the Savoy, where Frankie Manning made his name. I was like, that will be incredible to see and hear the music and the bands.”

Frankie Manning, widely considered the greatest Lindy Hopper of 30s and 40s, had become the inspiration of the Herräng Festival. He was a hero to Felix, but to the Black attendees it sounded like he was saying he wanted to go back in time to an era of segregation. After the panel, Herräng organizers began to discuss an idea for a special skit they wanted performed for the whole camp.

“A time machine where I would enter and come out at a house rent party. We wanted to have police come arrest someone on stage.”

Breai Mason-Campbell, another Frankie Manning scholar, called the skit cosplaying Jim Crow.

One night following this, LaTasha saw a dancer arrive for an event in blackface. She walked out and confronted the Herräng Dance Camp organizers. They said that their aim was to unite people from all over the world with a common interest in jazz culture”, adding, “We have no intention of politicizing the camp.”

The story told in Herräng was that Lindy Hop had faded away until it was revived in Sweden. They saw Frankie Manning’s style as the only authentic Lindy Hop. LaTasha saw things differently — Lindy Hop was always being passed around. It lived on in the continuum of Black dance that includes house and and hiphop. The Swedish dancers had codified Lindy Hop as a series of steps to master, and discouraged steps from modern styles. LaTasha felt like an outsider in her own culture.

May We Have This Dance?

LaTasha considered leaving Herräng, but ultimately didn’t. She’d come to learn, so she decided to stay. One night, a friend suggested she dance with someone new, and introduced her to a tall, cheerful twenty four yearold. All she could think was…

LATASHA: Oh, he’s one of the Swedes. But, the song started and he was like… “Hey. Do you want to dance?” And then…

FELIX: Step.

LATASHA: Step, step, triple step. The artist in me resisted, asking every step — did I do that right?

FELIX: We’re trying to hang on with each other.

LATASHA: Step, step, triple step.

Then LaTasha started to improvise, throwing in steps from house and hip-hop.

LATASHA: Ok, my feet are executing …is there a way that I can…?

FELIX: Whoa!

LATASHA: (vocalizing).

FELIX: Whoa!

LATASHA: Oh, yeah. OK. I hit that one.

FELIX: She just do what she wants!!

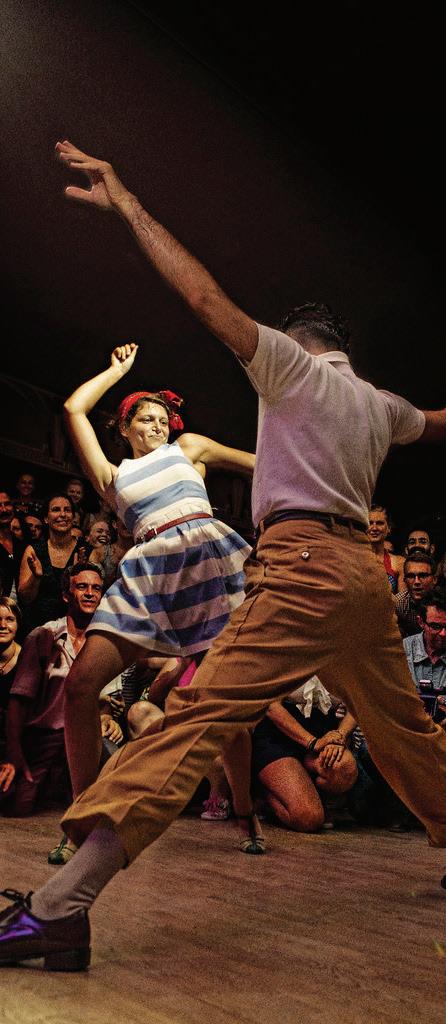

Felix could feel LaTasha hitting the rhythms, and the pair began speaking through movement. It was a conversation, full of surprising, delightful comments. LaTasha tried rhythmic explorations and Felix was right there with her.

LATASHA: “It was like a perfectly prepared tomahawk ribeye with corn on the cob and a perfect glass of red and a perfect creme brûlée.”

LaTasha could relax. It restored her sense of safety. After that summer, the pair found ways to keep dancing together. In 2019, they competed in the International Lindy Hop Championships — the same competition that Felix’s team used to dominate.

Felix still wanted to think of himself as the happy Lindy Hopper, and was still part of the Herräng inner circle. But LaTasha pushed him to speak up. Felix worried people might not hire him anymore. But dancing together had opened up a space between them, and LaTasha knew he felt differently.

LaTasha and Felix planned to teach together in Brazil and South Korea in 2020. Then the pandemic happened, and classes around the world were cancelled. One of the few events left was a virtual celebration of Frankie Manning on what would’ve been his 106th birthday, May 26, 2020. On May 25, George Floyd was murdered.

LaTasha calls herself a tradition-bearer. She wanted Felix to see himself not as a silent ally, but as an active partner helping to carry Lindy Hop forward. Felix found new ways to participate. He deepened his practice of improvisation. Latasha showed him how to bring more of himself and his own style into his dancing. He decided to end his involvement with Herräng.

LaTasha came up with a term that she hoped would create a role for non-Black dancers like Felix — cultural surrogate. It was an idea that made room for LaTasha, too.

“If a white community had not appropriated Lindy Hop, I probably would not have had any interaction with it, not in this way, not to this degree - to be able to learn it. There was a point in time where I felt like a cultural surrogate because I didn’t have a personal relationship with jazz - not in the way that I do now. I used to listen to it with my great grandmother. But that was my great grandmother’s relationship that I got to enjoy because I was with her. Then it became my personal relationship, because of the memories that it evoked in me.”