Nature as Design Mentor: exploring the role of the Earth's natural ecosystems as inspiration and guidance for sustainable human design

“lf the human is a designing animal and the Earth is its design studio, this animal is not a unique and distinct creature moving and thinking within that vast studio. The figure of the human is not sharply defined. lt is part of the living Earth that it designs in just as the living Earth is part of it. The material world, whether the flows in a river valley or in the veins of our own bodies, is never just outside, waiting for human thought and action.”

CONTENTS

1. POSITION

Introduction

Argument

2. PERSPECTIVE

Field of Research

Context

3. APPROACH

Method

Sources

4. DISCUSSION

Argument 1

Argument 2

5. CONCLUSION (Ex5) Findings

Future Directions

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Summary:

Nature-based design thinking is an expanding interdisciplinary field that draws from biomimicry, systems theory, and regenerative architecture. This essay explores how shifting from anthropocentric to eccentric design paradigms enables more ethical and symbiotic approaches to sustainable development. We argue that natural ecosystems provide not just inspiration but methodological guidance for material and structural innovation, as seen in Oxman’s and Pearce’s works. We also argue that ecological design must critique and transcend capitalist aesthetics that commodify nature, as noted by Escobar and Kimmerer. Ultimately, we conclude that nature should be engaged as a living mentor for co-evolutionary human futures.

Word Count: 100

Image-A regenerative architecture is a zero-energy, self-sufficient structure that breathes and adapts to its environment, repairing itself and reducing energy consumption while meeting the needs of its occupants and giving back to the community.

ReGen Villages, 2023

POSITION

Introduction

Human-centered design has historically viewed nature as a passive resource or symbolic muse. Yet, with growing environmental crises, there is an urgent call to reverse this paradigm. As Janine Benyus proposes, nature is a living repository of evolutionary intelligence, having "been innovating for 3.8 billion years."1 This highlights the fact that humans can learn a lot from nature, which is a natural reservoir of information for humans.

The concept of ‘Nature as Design Master’ advocates a radical restructuring of the traditional anthropocentric conception of the environment as a design resource. It argues that humans should shift from being masters of nature to humble learners of its regenerative mechanisms, adaptive strategies and co-evolutionary wisdom. Under this philosophy, designers should not confront or conquer nature but actively understand the operational logic of natural systems and find synergies between human design and ecosystems. Thus, the philosophy challenges conventional design paradigms and emphasises the integration of ecological balance and sustainable development principles into innovative design to build a future where humans live in harmony with nature.

Argument

This paper focuses on the key concepts of biomimicry, regenerative design and materials ecology to understand how nature can provide designers with inspirational processes that help people create solutions that are environmentally efficient. For example, Neri Oxman's research in the field of materials ecology demonstrates how the cross-fertilisation of biological systems with human technology can give rise to innovative materials that mimic natural processes, thereby driving the design transition towards sustainability.2 In addition, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley's work in Are We Human? Integration of ecosystems into the design of humanbuilt environments are crucial and advocates a design thinking that is interdependent with nature, rather than fragmented.3

This paper critically examines theoretical perspectives and practical examples to illustrate how the concept of ‘nature as a design mentor’ can provide a guiding framework for sustainable regenerative design practice. Transforming nature from a passive resource to an active design collaborator not only expands the possibilities of design but also leads to a design that is more respectful of ecological laws and more conducive to the long-term well-being of humans and ecosystems.

PERSPECTIVE

Field of Research

Context

This research falls within sustainable and ecological design, particularly the study of nature-inspired systems thinking, regenerative frameworks, and posthumanism theories that reconceptualise nature as a cognitive partner. Nature as a mentor shifts design from tool-based intervention to relationship-based practice. The development of superhydrophobic self-cleaning materials was inspired by the observation of the water-repelling properties of lotus leaves, a phenomenon known as the ‘lotus effect’.4 The principle is that the lotus leaf surface has a composite layer of micron-scale papillary structures and nano-scale wax crystals, which allows water droplets to roll off quickly after contacting the surface, taking away tiny particles such as dust along the way, thereby achieving a self-cleaning function without external cleaning intervention5 (See figure 1).

This mechanism has been widely studied and cited by researchers such as Mouli Konar and Thimmaiah Govindaraju, who pointed out that ‘the concept of making self-cleaning material surfaces is always inspired by elegant designs in nature’.6 This not only reflects the inspirational role of nature in functional design, but also indicates that bionics is gradually shifting from static imitation of natural forms to dynamic simulation of natural functional mechanisms. This shift indicates that nature is no longer just an object to be copied but is regarded as a design collaborator with cognitive and guiding potential, thus laying an important theoretical foundation for the concept of ‘nature as a design mentor.’

Figure 1. a) Self-cleaning effect observed on a lotus leaf (lotus effect). b) Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image showing the microstructures on the lotus leaf surface. c) Nanoscale wax tubular formotions located atop the micropillar structures of the lotus leaf. d/e) Schematic illustration of the lotus leaf’s self-cleaning mechanism. Konar, Roy, and Govindaraju, 2020, 3.

In her groundbreaking work Biomimicry, Janine Benyus transformed nature from a decorative metaphor in the past to a functional mentor,7 proposing that we should draw deep inspiration from the resilience logic of ecosystems and develop sustainable design principles. Continuing this idea, Michael Pawlyn8 demonstrated the practical application of bionics in architectural systems, emphasizing that nature is not only a source of inspiration, but also can lead technological innovation.

Rachel Armstrong's9 Living Architecture further expands this framework, advocating that architecture should be regarded as a system with living characteristics that can grow, adapt, and even self-repair like metabolic organisms, thereby redefining the boundaries of human interaction with the environment.

Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley have conducted a profound discussion on the ontological status of design in their co-authored work Are We Human?10 They challenged the traditional anthropocentric view of design, pointing out that the body and the environment are not independent entities, but the result of co-construction and evolution in continuous interaction.

This view echoes the discussion of Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi in The Systems View of Life,11 which reshaped the context of design by revealing the complex interconnectedness between life systems, emphasizing that design should serve the coordination and continuation of the life network

rather than override nature. Jeremy Lent also provided strong support for this paradigm shift in The Web of Meaning.12 He advocated that contemporary society should get rid of the linear cognitive model that dominates nature and turn to a worldview based on interconnection and interdependence, laying a cognitive foundation for the revival of design civilization with nature as its mentor.

In her Material Ecology, Neri Oxman13 uses a technobiological perspective to view materials as co-evolving participants in the design process. Her practice echoes Donna Haraway's14 idea of ‘living with dilemmas’, calling on designers to stay connected to the future of multiple species rather than relying on shortcuts brought by technological innovation. The concept of reflective design proposed by Phoebe Sengers15 criticizes the implicit assumption of technological neutrality and advocates the cultivation of critical self-awareness in the design process to reveal the power structure and cultural bias behind the design. In Mushrooms at the End of the World,16 Anna Tsing breaks the teleological narrative of progress and proposes a design model based on uncertainty and spontaneous collaboration, emphasizing the possibility of reimagining symbiosis and recovery from ruins. David Orr's Earth in Mind and Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass17 both emphasize that design must be deeply rooted in ecological literacy and cultural humility and put the relationship between man and nature back based on respect and reciprocity.

APPROACH

Method

This paper adopts a research method that combines theoretical guidance with case analysis and conducts in-depth thinking and analysis of the arguments through relevant works by scholars and practitioners in the fields of natural sciences and bionics. At the same time, it integrates interdisciplinary methodologies such as ecological design, regenerative design and architectural design, and strives to build a multi-angle interpretation framework leading to the symbiosis of human design and nature.

Sources

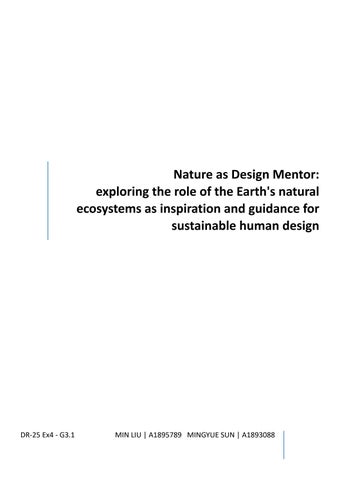

Mick Pearce’s Eastgate Centre in Harare uses a termite mound structure to simulate its ventilation and temperature regulation mechanisms in the building structure, vividly demonstrating the application value of biomimicry18 in energy-efficient buildings (See figure 2). Although the project has achieved remarkable results in energy efficiency, it is often criticized for only treating nature as a tool, ignoring the deep understanding and reciprocity of natural systems and the interaction with the broader social-ecological system. As Tony Fry emphasizes in Political Design,19 ‘sustainability’ without ontological reflection is not enough; truly transformative design activism must engage in a deep critique of the mechanisms that continue to exacerbate the environmental crisis.

The Eden Project in Cornwall20 is a model of transforming an abandoned post-industrial quarry into an educational eco-park. Through giant greenhouses, biodiversity displays and the use of sustainable technologies, the project intends to arouse public attention to environmental issues and provide a space for ecological learning. However, as critic Ingrid Stefanovic21 points out, similar projects also face the risk of aestheticizing, commodifying and entertaining nature. When nature is over-packaged as a visual spectacle, ecological interaction may degenerate into a shallow consumer experience, thereby weakening its original potential for immersive education and emotional connection.

Aithal, 2020; Samimi, 2011.

The mycelium material experiments conducted by Phil Ross22 and academic institutions such as the MIT Media Lab indicate that human design practice is moving towards a new paradigm with material agency at its core (See figure 3). As a material form rooted in the logic of symbiosis and decomposition, mycelium not only embodies the local nature of ecological cycles but also symbolizes a powerful response and challenge to the Western-centric design paradigm. However, such forward-looking explorations still must face the cultural inertia brought about by deeprooted industrial standards and capital logic. As design anthropologist Arturo Escobar23 criticized in Designing the Multiverse, mainstream design thinking continues to marginalize non-Western, non-technocratic knowledge systems and ignores the complex reality and practical logic under a diverse worldview.

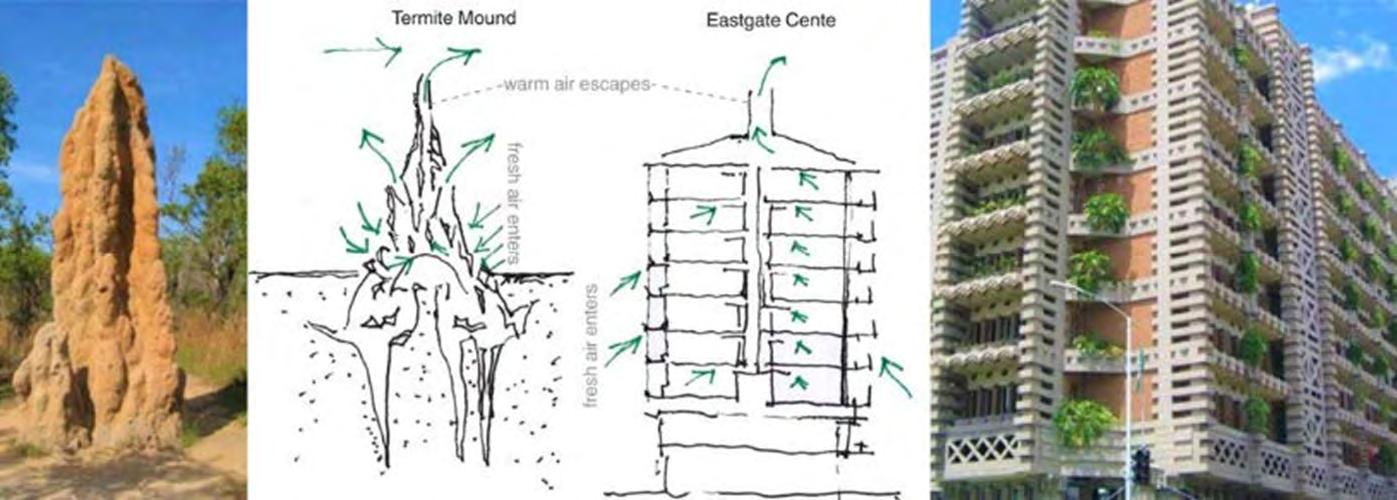

The design concept of ‘cradle to cradle’24 (See figure 4) attempts to reconstruct the production system into a closed-loop metabolic mechanism, emphasizing the technical path of waste reuse and resource circulation. However, this technocratic optimism has also been questioned by scholars such as Cameron Tonkinwise,25 who point out that truly sustainable transformation is not only about technology, but also requires profound behavioral changes, institutional innovations and cultural reconstruction. In this context, the Bionic Institute and the speculative design advocated by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby26 proposed a design logic that goes beyond problem-solving and instead imagines an alternative future centered on empathy, slowness, and deep connections. At the same time, Ursula K. Le Guin's ‘Zhopping bag theory’ and Timothy Morton's27 ecological philosophy also provides important conceptual frameworks for such practices. Together, they promote the shift of design toward narrative diversity and a posthuman perspective.

Figure 4. Cradle to cradle, it advocates that the entire life cycle of a product should be like a circular system in nature, where materials do not become waste after use, but continue to participate in a new life cycle as a resource.

Cradle to Cradle NGO, n.d.

DISCUSSION

Argument 1: Nature as Technological Teacher

We argue that biomimicry offers a systemic shift in architectural thinking by emulating nature’s adaptive and cyclical strategies—treating nature not as an object but as a model of systemic intelligence, where buildings are designed with feedback loops and ecological integration in mind, materials interact and grow in reciprocity rather than dominance, and architecture learns from natural cycles to achieve resilience, mutual flourishing, and regenerative performance across time and scale.

P1: Systemic Shift in Architectural Thinking

Nature functions as a highly integrated system, where each part plays a role in maintaining the whole. Benyus states, “life creates conditions conducive to life,” encouraging architects to design with feedback loops and systemic resilience in mind.28 Capra and Lent similarly advocate for ecological thinking in architecture, arguing that buildings should no longer be isolated from their surroundings, but woven into environmental processes.29 Rather than seeing nature as an object, this view positions it as a systemic intelligence—shifting design from isolated problem-solving toward holistic performance across time and scale.

P2: Emulating Nature’s Adaptive and Cyclical Strategies

The Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe, designed by Mick Pearce, exemplifies how biomimetic architecture can replicate adaptive systems in nature. Drawing from termite mounds, the building uses passive ventilation to regulate temperature, reducing energy use by up to 90%.30 This project

does more than copy form—it models ecological function. As scholars have discussed, design becomes adaptive not by resisting the environment but by learning from its inherent cycles, such as airflow, heat, and moisture exchange.31

P3: Living Materials and Material Intelligence

Robin Wall Kimmerer emphasizes that “all flourishing is mutual,” reframing our relationship with nature from exploitation to exchange.32 Architects like Neri Oxman echo this ethic in her “material ecology” philosophy, where materials are designed to interact with their surroundings rather than dominate them.33 Phil Ross’s “mycotecture,” made from fungal mycelium, represents this in practice—buildings are grown, not imposed.34 Together, these examples show that nature-as-teacher is not only a design model but a philosophical stance: one that values care, dialogue, and regeneration over extraction (See figure 5).

Argument 2: Nature as Ethical and Cultural Guide

Beyond technical efficiency, biomimicry invites a deeper ethical and cultural reorientation in design—one that rejects human dominance in favor of reciprocity with nature, embraces Indigenous and posthuman design epistemologies within a pluriverse of co-authorship, and resists commodifying the natural world by instead practicing slow, attentive, and relational design grounded in humility, care, and mutual flourishing.

P1: Operating in Reciprocity Rather Than Dominance

Design rooted in reciprocity challenges extractive models of humannature relationships. Robin Wall Kimmerer argues that “all flourishing is mutual,”(See figure 6) a perspective grounded in Indigenous wisdom where giving back is as essential as taking.35 This philosophy positions nature as a partner in co-creation, not a passive resource. Ursula Le Guin’s speculative fiction and Timothy Morton’s concept of the “mesh” both reinforce the idea that human design must acknowledge its entanglement with the more-than-human world.36 Rather than imposing control, ethical design emerges from attentive listening and mutual respect across species and systems.

P2: Pluriverse and Posthuman Design Futures

Design anthropologist Arturo Escobar advocates for a pluriverse—a world where many worlds fit—urging architects to move beyond universalizing Western design logic.37 Instead, design should emerge through coauthorship with ecological and cultural agents. In this framework, Indigenous knowledge systems are not referenced as exotic supplements but embraced as legitimate and essential design epistemologies. Beatriz Colomina’s scholarship similarly calls for decentring the human and recognizing nonhuman agencies in spatial design.38 Together, these voices promote posthuman, pluralist futures where design is shaped not just by humans, but with the land, the species, and the stories embedded in place.

P3: Critical Reflection Against Commodification

Biomimicry risks becoming superficial if nature is treated as a catalog of forms rather than a sentient collaborator. Scholars like Phoebe Sengers, Zoran Stefanovic, and Anna Tsing critique the aestheticization and commodification of nature in design.39 Their work warns against quick technological translations that ignore ecological context and cultural meaning. Tsing, in particular, advocates for “slow design” that attends to uncertainty, decay, and improvisation—qualities often excluded in modernist, efficiency-driven design.40 Ethical practice, in this light, means designing not just for performance but with patience, attention, and care.

CONCLUSION

Reframing nature as a design mentor offers a profound shift in the values and methodologies of sustainable architecture. Through both biomimetic strategies and ethical reflection, this paper demonstrates that nature is not merely an inspiration or tool but an active collaborator— technologically, culturally, and philosophically. By learning from nature’s cyclical systems, as seen in passive ventilation or self-cleaning surfaces, design gains resilience and environmental harmony.41 At the same time, acknowledging nature’s agency and cultural embeddedness demands designers to move beyond anthropocentrism, embracing posthuman, pluriverse, and reciprocal perspectives.42

This dual lens—of nature as both technological teacher and ethical guide—highlights the limitations of superficial sustainability and calls for a deeper reconfiguration of design thinking. It urges a design practice grounded not only in ecological intelligence, but also in humility, cultural sensitivity, and critical awareness of power structures.43 Ultimately, only by aligning with nature’s logic—adaptive, co-evolutionary, and interconnected—can we cultivate regenerative futures where human and non-human systems thrive together.44

ENDNOTES

1 Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 213-215.

2 Neri Oxman, "Material Ecology," Architectural Design 80(4) (2010): 78–85.

3 Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 22.

4 Benyus, 1997, 118-121.

5 Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry in Architecture (London: RIBA Publishing, 2011), 2731.

6 Rachel Armstrong, Living Architecture (London: TED Books, 2012), 7-10.

7 Benyus, 1997, 8-17.

8 Pawlyn, 2011, 137-141.

9 Armstrong, 2012,31-36.

10 Colomina, 2016, 33.

11 Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi, The Systems View of Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

12 Jeremy Lent, The Web of Meaning (London: Profile Books, 2021).

13 Oxman, 2010, 81-83

14 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

15 Phoebe Sengers et al., “Reflective Conference on Critical Computing

16 Anna Tsing, The Mushroom University Press, 2015).

17 David W. Orr, Earth in Mind Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

18 Orr, David W. Earth in Mind

19 Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry

20 Pearce, Mick. Design for

21 Ingrid Stefanović, “Phenomenological of Environmental Education

22 Phil Ross, “Mycotecture,”

23 Arturo Escobar, Designs

24 William McDonough and Point Press, 2002).

25 Cameron Tonkinwise, “Redesigning Papers 3, no. 3 (2005): 129

26 Anthony Dunne and Fiona

27 Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Nature (New York:

Design 80(4) (2010): 78–85.

Notes on an Archaeology of RIBA Publishing, 2011), 27Books, 2012), 7-10. of Life (Cambridge: Books, 2021).

Duke University Press,

15 Phoebe Sengers et al., “Reflective Design,” Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing (2005), 49–58.

16 Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

17 David W. Orr, Earth in Mind (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2004); Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

18 Orr, David W. Earth in Mind. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2004.

19 Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry in Architecture.

20 Pearce, Mick. Design for the Eastgate Centre, Harare. Harare: Arup, 1996.

21 Ingrid Stefanović, “Phenomenological Encounters with Place,” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 10, no. 1 (2005): 173–186.

22 Phil Ross, “Mycotecture,” Architectural Design 82, no. 2 (2012): 88–95.

23 Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse (Duke University Press, 2018).

24 William McDonough and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle (New York: North Point Press, 2002).

25 Cameron Tonkinwise, “Redesigning Design Education,” Design Philosophy Papers 3, no. 3 (2005): 129–150.

26 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything (MIT Press, 2013).

27 Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of

the World (Grove Press, 1986)

28 Benyus, 1997, 5.

29 Capra, 2014, 11; Lent, 2021,

30 Mick Pearce, Design for and Architects, 1996).

31 Benyus, 1997, 10.

32 Kimmerer, 2013, 183.

33 Oxman, 2010, 81-83

34 Ross, 2012, 88-95.

35 Kimmerer, 2013, 189.

36 Guin, 1986, 152.

37 Escoba, 2018, 33.

38 Colomina, 2016, 40.

39 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005,

40 Tsing, 2015, 24.

41 Benyus, 1997, 10.

42 Escoba, 2018, 33; Lent,

43 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005,

44 Capra, 2014, 20; Lent, 2021,

Nature (New York: Design 80(4) (2010): 78–85.

Notes on an Archaeology of RIBA Publishing, 2011), 27Books, 2012), 7-10. of Life (Cambridge: Books, 2021).

Duke University Press, 15 Phoebe Sengers et al., “Reflective Design,” Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing (2005), 49–58.

Proceedings of the 4th Decennial (Princeton: Princeton Island Press, 2004); Robin Wall Milkweed Editions, 2013).

Island Press, 2004.

Harare. Harare: Arup, 1996. with Place,” Canadian Journal no. 2 (2012): 88–95. University Press, 2018). to Cradle (New York: North Education,” Design Philosophy Everything (MIT Press, 2013). Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of

16 Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

17 David W. Orr, Earth in Mind (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2004); Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

18 Orr, David W. Earth in Mind. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2004.

19 Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry in Architecture.

20 Pearce, Mick. Design for the Eastgate Centre, Harare. Harare: Arup, 1996.

21 Ingrid Stefanović, “Phenomenological Encounters with Place,” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 10, no. 1 (2005): 173–186.

22 Phil Ross, “Mycotecture,” Architectural Design 82, no. 2 (2012): 88–95.

23 Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse (Duke University Press, 2018).

24 William McDonough and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle (New York: North Point Press, 2002).

25 Cameron Tonkinwise, “Redesigning Design Education,” Design Philosophy Papers 3, no. 3 (2005): 129–150.

26 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything (MIT Press, 2013).

27 Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of

the World (Grove Press, 1986); Timothy Morton, The Ecological Thought -17.

28 Benyus, 1997, 5.

29 Capra, 2014, 11; Lent, 2021, 85.

30 Mick Pearce, Design for the Eastgate Centre, Harare (Harare: Arup Engineers and Architects, 1996).

31 Benyus, 1997, 10.

32 Kimmerer, 2013, 183

33 Oxman, 2010, 81-83

34 Ross, 2012, 88-95.

35 Kimmerer, 2013, 189.

36 Guin, 1986, 152.

37 Escoba, 2018, 33.

38 Colomina, 2016, 40.

39 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005, 70-75.

40 Tsing, 2015, 24.

41 Benyus, 1997, 10.

42 Escoba, 2018, 33; Lent, 2021, 85; Kimmerer, 2013, 189

43 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005, 70-75; Haraway,2016, 20-25.

44 Capra, 2014, 20; Lent, 2021, 30-40

the World (Grove Press, 1986)

28 Benyus, 1997, 5.

29 Capra, 2014, 11; Lent, 2021,

30 Mick Pearce, Design for and Architects, 1996).

31 Benyus, 1997, 10.

32 Kimmerer, 2013, 183.

33 Oxman, 2010, 81-83

34 Ross, 2012, 88-95.

35 Kimmerer, 2013, 189.

36 Guin, 1986, 152.

37 Escoba, 2018, 33.

38 Colomina, 2016, 40.

39 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005,

40 Tsing, 2015, 24.

41 Benyus, 1997, 10.

42 Escoba, 2018, 33; Lent,

43 Phoebe Sengers et al., 2005,

44 Capra, 2014, 20; Lent, 2021,

Primary Sources

Benyus, Janine. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Oxman, Neri. “Material Ecology.” Architectural Design 80(4), 2010: 78–85.

Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016.

Secondary Sources

Armstrong, Rachel. Living Architecture. London: TED Books, 2012.

Capra, Fritjof, and Pier Luigi Luisi. The Systems View of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Fry, Tony. Design as Politics. Oxford: Berg, 2011.

Inzerillo, Barbara. For Nature, With Nature: New Sustainable Design Scenarios. Cham: Springer, 2024.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Le Guin, Ursula K. “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In Dancing at the Edge of the World. New York: Grove Press, 1986.

Lent, Jeremy. The Web of Meaning. London: Profile Books, 2021.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press, 2002.

Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Pawlyn, Michael. Biomimicry in Architecture. London: RIBA Publishing, 2011.

Ross, Phil. “Mycotecture.” Architectural Design 82, no. 2 (2012): 88–95.

Sengers, Phoebe et al. “Reflective Design.” Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing, 2005: 49–58.

Stefanovic, Ingrid. “Phenomenological Encounters with Place.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 10, no. 1 (2005): 173–186.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

“Nature has been inventing for billions of years. What bettermodels could we ask for?"

-Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature

Checklist

Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

Inserted word count of the summary.

Inserted word count of the article.

Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

Researched and cited the required number of sources.

Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student 1: Student 2:

Name: Min Liu

Name: Mingyue Sun