YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

Loving Legacies

I HOPE ALL OF YOU enjoyed the summer months and were lucky enough to visit Yosemite. As we now look toward the remainder of the year, there is certainly something inspiring about visiting our majestic park and taking your favorite hike in the crisp, colorful fall season under a beautiful blue sky. I especially like seeing young children in the park — it could easily be the beginning of what may be their lifelong connection to this incredible place, as their parents start or continue traditions that can last for generations.

This issue highlights legacies of loving Yosemite. We spent time with some of our oldest fans, now in their 90s, who literally grew up in the park and attended the Yosemite Valley School together in the 1930s and ’40s. They are still connected to each other and the park, and their stories are as entertaining as they are inspiring. We also interviewed members of the Conservancy’s next generation of leadership — part of the Future Leaders Advisory Circle (FLAC) — some of whom began coming to the park as toddlers and some as adults. All share a deep commitment to Yosemite legacies of their own. In these pages, you’ll meet Yosemite’s “Welcoming Committee” — visitor information assistants who support the park through monthlong volunteer positions — including people who have been volunteering for decades and those who spent their very first summer here in 2024. You’ll find a photo montage of Yosemite “Then & Now”; maybe you’ll recognize some of your favorite buildings — maybe you won’t! Additional stories celebrate the 33rd Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series and the 25th anniversary of the Yosemite bear team, which has worked for more than a quarter-century to keep bears safe and wild.

Being inspired by the legacies of people and places is easy in Yosemite National Park. I hope this issue will help you reflect on the legacy you are providing for future generations through your ongoing support. Thank you!

Steve Ciesinski CHAIR

COVER Half Dome peaks over Stoneman Bridge and the Merced River on a crisp autumn day.

Yosemite’s Welcoming Committee

Visitor information assistants — veterans and first-timers — play a key role in keeping park visitors safe and happy. PAGE 14

Then & Now

Do you recognize the iconic landscapes, people, and structures of yesteryear? PAGE 18

Schoolhouse Rocks

Nonagenarian classmates from long ago learned their lessons both inside and outside the Yosemite Valley School. PAGE 4

Keeping Bears Wild

A quarter-century after Yosemite’s bear team began their efforts, people and bears are still learning to co-exist. PAGE 8

Etched in Stone

The beloved Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series celebrates 33 years of inspiration. PAGE 22

The Next Generation

Future Leaders Advisory Circle (FLAC) members bring innovative ideas and diverse voices to shaping Yosemite’s tomorrow. PAGE 28

Love Letters to Yosemite

Inspired by Thomas Hill and the Firefall, hiking up waterfalls, and human history, friends of the park share their stories. PAGE 32

Meet the Team: Emily Brosk

Yosemite Conservancy’s director of volunteer programs talks about what it’s like to run “adult summer camp.” PAGE 34

Junior Rangers

Your actions affect Yosemite! Play your way up the Mist Trail by making good choices in the park! PAGE 36

Through Your Lens

Park fans share their photos of Yosemite. PAGE 38

OUR MISSION Yosemite Conservancy inspires people to support projects and programs that preserve Yosemite and enrich the visitor experience for all.

SCHOOLHOUSE

Rocks

The Yosemite Valley School forged friendships and advocates who are as deeply rooted as the granite that shaped their childhoods

BY LAUREN HAUPTMAN

orn in the park, Michael Adams was a student at the Yosemite Valley School in the 1930s and ’40s. Life in Yosemite included attending class in the two-room schoolhouse, teaching skiing at Badger Pass, managing Tuolumne Lodge, and marrying his wife, Jeanne, in the Yosemite Valley Chapel, followed by a reception at The Ahwahnee. It was the same date, July 28, that his grandparents had been married under Bridalveil Fall. The Yosemite lineage comes through both sides of Michael’s family. His mother’s father was Harry Best, a landscape painter and political cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle, who opened “Best’s Studio” in a tent in the Valley, later becoming a park concessioner.

MICHAEL ADAMS, DICK OTTER, AND JANE LUNDIN (now in their 90s) all attended the Yosemite Valley School as young children. The building pictured was not the first, but the second school building constructed in the park.

Harry and Anne Best’s daughter, Virginia, married Ansel Adams in a newly constructed Best’s Studio in 1928. Virginia and Ansel turned the studio over in 1971 to their son and daughter-in-law, Michael and Jeanne, who renamed it The Ansel Adams Gallery that same year.

Yosemite is in Michael’s blood. And at age 90, he remains devoted to the park’s stewardship.

“I was fortunate to live in the wild environment,” Michael says. “Lots of people came up from the city for their week or two weeks. I lived it year-round.

“We went to school in the two-room schoolhouse with two teachers, one for the first four grades and one for the second four grades. Everybody got along, and it was fun. One of my strongest memories is of the ranger-naturalists coming to talk to us about the local programs.”

It’s a memory he has put to good use for the good of the park. He joined the Yosemite Conservancy Council in 1997, taking a post on the programs committee.

“I had a lot of knowledge of what had gone on in Yosemite over the years,” Michael says. “I knew many of the programs and had something to say from a different angle than the other members. And I had a lot of good friends there.”

One of those good friends is Dick Otter. Together, Michael and Dick attended Yosemite Valley School; worked as desk clerks in Camp Curry, Yosemite Lodge, and Wawona Hotel; and served on the Conservancy’s Council. They remain close to this day.

Dick moved to Yosemite at 2 weeks old, and his very first memory is of his mother taking him to the park administration building on July 15, 1938, to watch President Franklin D. Roosevelt come into Yosemite among a phalanx of motorcycles.

“My mother was killed in an automobile accident in about April of 1940, so I came to live with my grandmother in San Francisco; but I had seven wonderful years in the park as a very small child,” Dick says. “The Yosemite School helped me develop self-reliance. I used to walk two miles to school and two miles home every day — rain, shine, or snow.”

Dick’s father went back to work for the park when he returned from World War II, so Dick was able to spend summers in Yosemite until he graduated from college. Among his favorite memories are parties he and Michael Adams threw — at Michael’s mother’s urging — when they were teenagers.

“We used to have car dances outside the tunnel at the

LEFT: The Ansel Adams Gallery in Yosemite Valley. RIGHT: Jeanne and Michael Adams in the Mariposa Grove.

parking lot of West Valley View (now called Tunnel View),” Dick says. “We’d put down the tops on our convertibles, have the radio on, and dance out there. And then if you walk into the tunnel, about a third of the way in, there’s a little side terminal for fresh air. We’d go out there and neck, and that was kind of fun.”

His time in the park left an indelible mark — strong enough that Dick was instrumental in founding the Yosemite Fund, a predecessor of the Conservancy, to help pay for projects deemed important by the National Park Service. The first projects he remembers working on were the removal of a sewer plant near Bridalveil Fall, returning bighorn sheep to the backcountry, and rescuing DDTaffected peregrine falcon eggs. Dick served on the Council from its inception until 2023; he is now an emeritus director of the Conservancy.

Like Michael and Dick, their classmate Jane Lundin was formed as much — maybe more — by the environs as she was by the school. The San Francisco native lived with her grandmother, who taught at Yosemite Valley School when Jane was in sixth through eighth grades.

“It was quite wonderful,” Jane says. “I loved climbing up mountains. I’ve climbed next to the waterfalls and on a trail to Glacier Point that’s no longer used. I loved the freedom of having a bicycle and just being able to go where I wanted.

“Yosemite was a very nice island in a somewhat stressful childhood. Views and waterfalls and wonderful wildflowers — and back in those days, lots of bears. A bear once put his paws on the windowsill and listened to me practice the piano. I only saw him as he was leaving, but the neighbors said he was there for quite a while with his nose pressed to the screen just to the left of the piano.”

Jane spent her honeymoon with her second husband in Yosemite, around the same time she chose to honor her first husband’s memory with a gift to the Conservancy for the renovation of Bridalveil Fall.

“The last time we were in Yosemite, my first husband spent a lot of time photographing Bridalveil from across the river,” she says. “Yosemite was always a favorite place for both of us. He loved photography, and that day the wind was blowing the spray.

“I support Yosemite by contributing to Conservancy projects because I love the place — the time I lived there was the happiest part of my teens.”

“The Yosemite School helped me develop self-reliance. I used to walk two miles to school and two miles home every day — rain, shine, or snow.”

Dick Otter

EMERITUS MEMBER OF YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY BOARD AND COUNCIL

DICK OTTER , emeritus member of Yosemite Conservancy board and council, and his wife Judy Wilbur in Yosemite Valley.

KEEPING BEARS WILD

For 25 years, Yosemite's bear team has preserved the delicate balance between protecting visitors and rewilding bears

BY ZOE DUERKSEN-SALM

hree bear tags rest in Yosemite ranger Jeffrey Trust’s uniform pocket. They are the tags of bears that had become acclimated to humans and, as a result, posed a threat to visitor safety. They’re the tags of bears Trust had to help kill — and wishes he could have saved.

Those bears were born as all black bears are: afraid of humans, active during the day, and motivated by food. Once exposed to humans, though, bears begin to adapt. In national parks — where bears cannot be hunted — bears will learn that humans are, for the most part, not dangerous. They’ll find new tricks to grab food from backpackers; they’ll sneak into campgrounds at night to raid unattended food; and, if successful, they may become less fearful around people.

Park rangers do their best to keep bears wild, but bears that boldly approach people threaten visitor safety; and once a bear reaches this point, sometimes the only option is to kill it.

Trust has been a member of the bear team, a collective of Yosemite staff and community members dedicated to

educating visitors on bear-safe practices, since 1999. Over the past 25 years, the team’s efforts to encourage proper food storage, safe driving, trash removal, and more strategic human–bear management have drastically reduced the annual number of negative human–bear interactions.

Despite the program’s success, Trust carries the three bear tags wherever he goes to remember those bears and the tumultuous history of human–bear management in Yosemite National Park.

BEAR TEAM BEGINNINGS

Relationships between humans and bears in Yosemite have changed dramatically during the past century. In the early 1900s, bears became accustomed to human food from scraps they could gather at open dumps, which were common in the park, and food they’d receive from employees at bearfeeding shows for visitors’ enjoyment. In those early days, folks were unaware that with each feeding, bears were learning that humans had food and were not a threat.

By the 1970s, when the park began to bear-proof trash cans and close the dumps, bears had become reliant on these food sources and were passing along this behavior to offspring. Instead of backing down, bears refocused their attention on

BEAR-FEEDING PITS were created outside of Yosemite Valley — after the formal bear-feeding shows ended in 1940 — to lure bears away from populated areas.

PHOTO: (ABOVE) © COURTESY OF NPS.

“It was an exciting opportunity to create a program aimed at visitors. Shifting the focus from the bears to park visitors acting responsibly was instrumental to its success.”

Scott Gediman

PARK AFFAIRS OFFICER

taking food from cars and backpackers, regularly injuring visitors in the process.

In response, Yosemite implemented its first bearmanagement plan in 1975. But without increased funding for staff and bear-resistant trash and food lockers, the problems continued into the 1990s. Steve Thompson and Kate McCurdy, head staff in Yosemite’s wildlife program at the time, and their team worked tirelessly to manage human–bear incidents. It was an impossible task with limited resources.

The problem peaked in 1998 with nearly 1,600 documented bear incidents — when a bear causes property damage, is aggressive, or injures someone — totaling more than $650,000 in damage.

This dramatic rise in incidents captured the attention of news outlets, such as National Geographic , Dateline NBC , and Nightline , and prompted widespread national coverage of the “Yosemite bear problem.”

“National media attention was instrumental in raising awareness,” says Scott Gediman, the park’s public affairs officer of 28 years. “It’s because of one of these programs that Thompson and I connected with a member of Congress, who secured $500,000 annually in federal funding for bear management in Yosemite.”

It was this funding that allowed Thompson and McCurdy — along with McCurdy’s successor, Tori Seher, and others in the park — to develop and launch Yosemite’s interdivisional bear team in 1999.

A BEAR traverses the Valley floor under the shadow of El Capitan.

A

by visitors. Bears can easily become dependent on human food sources and will begin to seek out and steal food from visitors — potentially endangering visitor safety in the process.

“With this new funding, Kate, Steve, and Tori began a new era of proactive human–bear management for the park,” says their successor, Caitlin Lee-Roney, a Yosemite wildlife biologist. “Their leadership is the reason the park has such a successful bear program today.”

With increased staffing and funding, suddenly everyone in the park — from rangers to store clerks to campground hosts — was part of the solution. In that first year, the team educated visitors on proper food storage, better managed park trash, enforced food-storage regulations, and began managing bears in new ways. They also hosted an annual Bear Awareness Day and a spring press conference on bear safety. In just the first year, documented bear incidents were cut in half.

“It was an exciting opportunity to create a program aimed at visitors,” Gediman says. “Shifting the focus from the bears to park visitors acting responsibly was instrumental to its success.”

The Yosemite Association and the Yosemite Fund (now collectively the Yosemite Conservancy) also made essential contributions to human–bear management at that time. Donors funded and installed new bear boxes, and the association began renting bear-proof canisters to visitors. In

more recent years, the Conservancy has funded the creation of the Keep Bears Wild website, the purchase of GPS collars to track bears in the park, and other key efforts.

“After several encounters with bears stealing my food on backcountry hikes, I wanted to fix the problem,” says Dave Dornsife, chair of steel manufacturer Herrick Corporation and a Conservancy board member.

It was Dornsife and his wife, Dana, who supplied steel and designers to develop the original Yosemite bear-proof food lockers.

“We teamed up with the National Park Service and created a design that worked so well that we have donated hundreds of boxes,” he says.

A NEW PHASE OF MANAGEMENT

The first 12 to 15 years of management required intense work from the bear team to de-habituate bears that had already learned how to reap the benefits of visitors. This meant late nights for staff and scaring off dozens of bears — yelling, using noisemakers, and shooting them with rubber slugs and bean bags to retrain them to be frightened of humans.

BEAR FAMILY eats human food left behind

PHOTOS: (ABOVE) © DAN SPARKS. (RIGHT) © NONIMATGE.

“It took well over a decade to get to a point where it felt like we caught up,” Lee-Roney says.

Now, bear incidents have dropped from 1,600 to fewer than 50 per year, and the bear team has transitioned to a monitoring and proactive management phase — trying to prevent new bears from learning behaviors that get them into trouble. The team can now focus on educating visitors on appropriate behavior toward bears (see right side bar).

In 2024, on the 25th anniversary of the bearmanagement program, day-use visitors are the newest challenge. Lee-Roney and Trust note that many don’t realize bears will still steal food from cars or lunch spots during the day. Unlike with most overnight visitors, the park doesn’t have a direct way to contact day visitors. Trust notes that if the park implements a permanent reservation system in the future that includes day visitors and requires an email to complete the reservation, it could provide a new way to educate visitors before they even set foot in Yosemite.

Trust recalls the late Steve Thompson saying that bears will always find the gaps in our program.

“This is a program that will require vigilance forever,” Trust says. “Even as negative human–bear incidents decline, it’s still up to us, as employees and visitors, to keep bears wild.”

BEAR-SAFE PRACTICES

DRIVE SLOWLY

Dozens of black bears are struck by vehicles each year. Please drive slowly and alertly, and obey posted speed limits. Pay attention: Every time you see a “Speeding Kills Bears” sign in the park, that’s a location where a bear has been hit by a vehicle this year.

STORE YOUR FOOD

Food and scented items should ALWAYS be properly stored — in bear-proof lockers and canisters, buildings, and fully enclosed hotel rooms (NOT tents or canvas tent cabins) — to prevent bears from becoming conditioned to human food. When food is out of storage, it should be kept within arm's reach at all times.

Interested in bear safety?

Donors can help keep bears wild by sponsoring a bear-proof food locker, which will include a plaque recognizing you or a loved one. Learn more at yosemite.org/bearbox.

KEEP YOUR DISTANCE

If you see a bear in a wild place, watch quietly from a distance of at least 50 yards. If a bear approaches you, act immediately to scare it away by yelling as loudly and aggressively as possible.

Learn more at KeepBearsWild.org

Scan to learn more

PHOTOS: (RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM) © MICHAEL VI. © YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/NOEL MORRISON. © SED PHOTOGRAPHY.

YOSEMITE’S WELCOMING COMMITEE

Volunteer visitor information assistants are an essential part of visitors’ safety and experience at Yosemite National Park

BY ZOE DUERKSEN-SALM

enn Bennett is headed out for his 284th volunteer day in Yosemite National Park. It’s May; melting snow brings water to the falls, warmer weather welcomes new guests, and the visitor information assistant volunteers have returned for their monthlong summer positions.

In the busy season — May through September — Bennett and fellow volunteers act as a welcoming committee in the park. While National Park Service (NPS) rangers are stationed inside visitor and wilderness centers, the volunteers are placed at popular lookouts, arrival points, trails, and other areas where visitors are likely to need assistance.

“Yosemite is humongous. For a first-time visitor trying to wrap their head around the scale of the park and how to orient and connect, it can be mindnumbing,” says volunteer program director Emily Brosk (more about her on page 34). “That’s really why the visitor information assistants are important.”

The volunteers are always ready to help visitors orient themselves to current conditions and plan the day ahead, and their characteristic blue shirts make them easy to spot. Their joyous attitude and enthusiasm for Yosemite also give them away.

In Bennett’s eight seasons as a volunteer, he’s answered, “Where’s the nearest bathroom?” and “Where can I see a bear?” more times than there are miles of trails in Yosemite (see page 8 for how the Yosemite community is protecting bears). Yet Bennett enjoys being able to share his love of Yosemite

VOLUNTEER visitor information assistants support visitors with important information regarding park operations, safety precautions, and more.

PHOTO: © YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/MARK MARSCHALL.

Scan to learn more about our visitor information assistant program

with new visitors and help others make lasting memories, as he has during the past 50 years.

“You can make a visitor’s experience for them just by giving them some advice,” he says.

Bennett also loves the camaraderie among volunteers. He reminisces about evenings back at camp (volunteers share campsites throughout the month) where they gather around campfires to get to know one another and discuss unique questions visitors have asked.

“The purpose of this is not, you know, to get a free campsite; it’s to take some of the stress off the NPS,”

Bennett says. “But part of the joy of volunteering is you get to make new friends who become lifelong friends.”

In June, a new cohort of volunteers takes the helm, bringing their own traditions and veteran volunteers. Among them are Peggy and the Pinecones — a group of eight that performs classic songs rewritten with a Yosemite twist by volunteer Peggy Schubert. Each new song is a love letter to Yosemite, starting with Schubert’s first rewrite, “Yosemite Valley” to the tune of “Red River Valley,” to a more recent rendition of “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” but as “I Want to Climb Half Dome.”

The Schuberts — Peggy and her husband, Paul — have developed their passion for Yosemite during 10 volunteer seasons. As New York residents, the two had only been to Yosemite twice before their volunteer journey began. Since then, they’ve made new friends, spent nearly 300 days living in the park, and shared their new Yosemite knowledge with other visitors.

“I’ve always appreciated that the program allows us time off to experience the park on our own,” Schubert says. “We can go off on our own hikes and then have the experience of being there to share with people.”

Schubert and Bennett represent the typical volunteer: Yosemiteobsessed and retired. When the program began in the 1980s, the opportunity to volunteer was considered a donor benefit. Combined with the monthlong commitment, the result has been an amazing base of retired and dedicated volunteers in their 70s and 80s.

“Over the years, we’ve started more targeted recruitment to reach people who aren’t solely Conservancy donors or retirees,” Brosk says. “Spanish speakers, people of color, folks in the workforce — and it’s very much working.”

Joining Schubert and the June cohort for the first time are Jonathan Puentes and Jen Lincoln. The couple — ages 30 and 28, respectively — live and work in the Bay Area, spending as much of their free time as possible outside hiking, backpacking, and scouting the best national park Bloody Marys.

Puentes and Lincoln noticed that younger visitors seem to gravitate toward them for information. Lincoln thinks millennial visitors might just

TOP: Visitor information assistant Dyane Jackson volunteers at Olmsted Point.

BOTTOM: Two visitor information assistant volunteers — Joyce Mason (left) and Sonya Edwards — support a park visitor at the Mist Trail trailhead.

be excited to talk to someone their own age.

“And I had a really long beard,” Puentes adds. “So all the backpackers would come to me asking, ‘Where are the showers?’”

Equally important to diversity in volunteer ages is diversity in backgrounds and languages. It came as no surprise to Puentes that encountering someone who speaks your language in the middle of Yosemite would be comforting. He notes that people would see “Puentes” on his nametag and ask if he speaks Spanish.

He recalls a time when he gave advice on Yosemite activities in Spanish to a dad: “He kept coming back to my stand and would say, ‘We finished, what else can we do?’ and at the end of the day he asked, ‘Are you working again tomorrow?’ He was just so excited.”

Of course, the couple also found time to enjoy Yosemite. To volunteer for a full month, they had to bank all their time off and skim down on other vacations. While they admit it was tough to volunteer while working full

time, they believe it was “1,000%” worth it.

“We’re going to do everything we can to figure out how we can come back next year,” Lincoln says. “It was the best month of our lives.”

At the end of September, the final cohort of volunteers says goodbye to Yosemite for the off-season. Next year, much will stay the same, visitors will learn valuable information from our volunteers, Peggy and the Pinecones will rewrite another hit song, and volunteer friendships will be forged around camp.

Brosk hopes that, bit by bit, the program will grow to include a more diverse volunteer base (perhaps even college students on summer break), additional support for NPS staff, and extra trainings to enrich the volunteer experience.

“Volunteers are some of the hardest working people you’ll ever meet,” Brosk says, “and they’re also having fun and enjoying Yosemite just as much as the visitors they help!”

Give the Gift of a

Yosemite Experience

From naturalist-led hikes and guided birding programs to instructor-led art classes and retreats, Yosemite Conservancy's professional artists and expert naturalists will help you experience Yosemite in a new way.

Get your gift card now for Conservancy-led experience in the 2025 season.

Every booking with Yosemite Conservancy helps preserve the natural beauty of the park.

*Some programs include park entry/day-use reservations.

NOW THEN& YOSEMITE VALLEY

BY HOLLY YU

Connecting Visitors to Yosemite’s Natural and Cultural History

From celebrating diverse stories to cutting-edge conservation science, Conservancy-supported interpretive retail spaces connect visitors with Yosemite's past, present, and future.

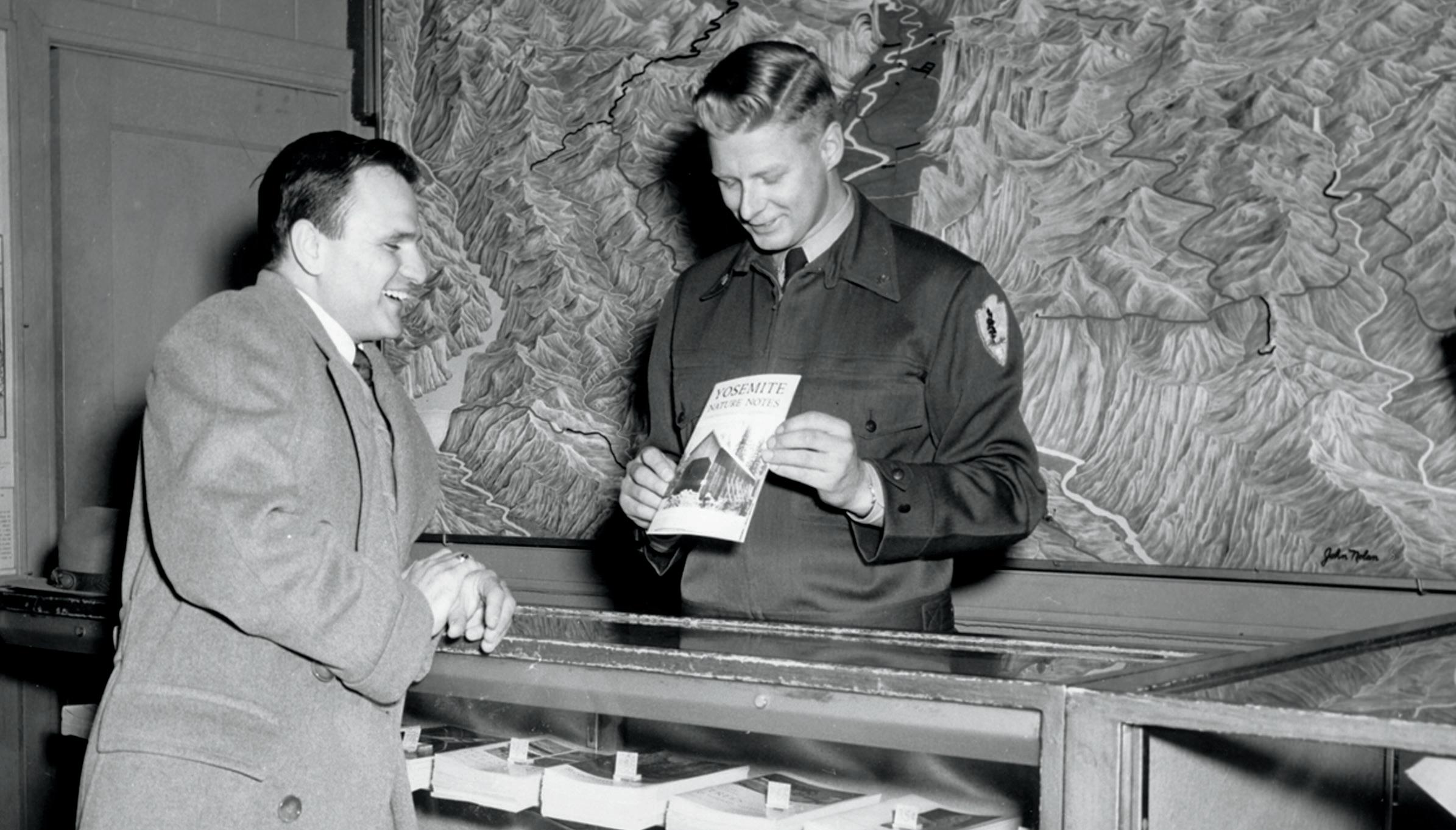

THEN

A Yosemite National Park staff member shows the original Yosemite Nature Notes to a visitor. Yosemite Nature Notes lives on as a series of video shorts, easily found on YouTube.

NOW

Yosemite Valley Bookstore Operations Manager Olotumi Laizer interacts with visitor at Yosemite Valley Welcome Center.

PHOTOS: (TOP TO BOTTOM) © COURTESY OF NPS. © BLAKE JOHNSTON.

Happy

Isles: From a

Fish Hatchery to the Home of the Art and Nature Center

Hook, line, and watercolors? The building at Happy Isles has served many purposes throughout the years. The structure was built in 1927 by the state of California as a fish hatchery to stock lakes and streams. The program ended and the building was transferred to the National Park Service in 1956. Today, Happy Isles is home to the Conservancy’s Art Program.

THEN

The Fen Restoration from Parking Lot to Natural Ecosystem

Yosemite National Park is always striving to find the balance between providing for visitors’ experience of the park and protecting the park’s natural resources. Looking at the Happy Isles’ Fen today, many would have no idea this bubbling wetland was a paved parking lot nearly a century ago.

THEN

A parking lot was built over the fen in 1928. A series of restoration projects beginning in the 1980s — led by the late restoration enthusiast Marty Acree — helped restore the area's natural hydrology.

NOW

Participants in a nature journaling class sit on the boardwalk over the restored fen.

NOW

Artist Alice Lee sketches with participants in an indoor drawing workshop at Happy Isles Art and Nature Center.

The fish grown in the hatchery were sent to stock High Sierra lakes and streams for recreational fishing.

PHOTOS: (TOP TO BOTTOM) © COURTESY OF NPS. © YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/KRISTIN ANDERSON.

PHOTOS: (TOP TO BOTTOM) © COURTESY OF NPS. © YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/LORA SPIELMAN-DELL ISOLA.

Meadow Restoration Work in Yosemite Valley

Meadows in Yosemite Valley, since time immemorial, have required care and attention. In more recent years, working with the associated Tribes, Yosemite’s fire management program has begun to bring back the Indigenous knowledge around cultural burnings to maintain meadows.

THEN

A group pulls invasive plants in the mid-1900s.

NOW

Student volunteers from the donorsupported Yosemite Leadership Program work on a stewardship project.

Legendary Yosemite Valley Trails and Hotels

As a tourist destination, Yosemite Valley has always offered visitors incredible treks and remarkable accommodations, from Hutching’s Hotel to the High Sierra Camps to the Stoneman Lodge. La Casa Nevada was once nestled along what is, today, one of the most highly trafficked trails in the National Park Service.

THEN

La Casa Nevada, also known as the Snow Hotel, was a popular spot for adventurists to stop for food and rest.

NOW

Although La Casa Nevada no longer exists, hikers continue to trek to Nevada Fall and beyond.

PHOTOS:

PHOTOS:

Cultural Demonstrators of Yosemite Valley

Cultural demonstrators have had — and continue to have — an important role since the National Park Service began providing interpretation to the public. A lineage of knowledgeable and talented demonstrators of the Indian Cultural Program share the story of the associated Tribes of Yosemite.

THEN

One of the first of many American Indian woman cultural demonstrators, Maggie Howard, makes acorn cookies in the 1930s.

NOW

Cultural demonstrator and ranger Ben Cunningham-Summerfield leads a walking tour showing traditional Indigenous housing.

PHOTOS: (TOP TO BOTTOM) © YOSEMITE HISTORIC PHOTO COLLECTION (RL-12801).

© YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/AL GOLUB

Stone ETCHED IN

BY GRETCHEN ROECKER

Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series celebrates its 33rd year as a “lively place” brimming with inspiration

rom a distance, the stone building nestled on a slope north of the Tuolumne River, between Pothole Dome and Lembert Dome, could be a geologic formation. Up close, details tell the structure’s story. Granite rocks form the rough walls. Lodgepole pine logs serve as rafters. Inside, the single room houses bookshelves, wooden tables, and a fireplace. A plaque declares: Parsons Memorial Lodge has been designated a National Historic Landmark.

“Parsons is such a unique space,” retired

Yosemite ranger Margaret Eissler says. “It’s part of the landscape, and it breathes in the outdoors.”

Eissler is deeply familiar with the lodge, which the Sierra Club built in 1915 in honor of adventurer and activist Edward Parsons to serve as a High Sierra headquarters, reading room, and gathering space. From 1956 to 1961, Eissler’s parents were summer caretakers of the lodge and surrounding property. She recalls the lodge, designed by Mark White of the Bay Area architectural firm Maybeck and

“What’s spoken or shared in Parsons radiates beyond the park boundaries … The presentations can broaden perspectives and deepen visitors’ connections with the park and even their own home places in unexpected ways.”

Margaret Eissler

YOSEMITE PARK RANGER

White, as a “lively place” where campers stopped by to share stories, peruse hiking and climbing guides, and shelter from storms. After their final caretaking season, the family regularly returned to Yosemite’s high country.

When the Sierra Club sold its 160 acres in Tuolumne Meadows to the National Park Service in the 1970s, Yosemite Natural History Association (now Yosemite Conservancy) volunteers opened the lodge again to the public. Nearly 20 years later, in 1992, Eissler — by then working as an NPS ranger naturalist — helped dream up a celebration at the lodge that would honor the Sierra Club’s 100th anniversary and the legacy of the space.

“We wanted to celebrate all the people who had passed through and their stories,” Eissler says. “It felt so right to bring the building back to life as I had remembered it.”

That centennial gathering, which featured 15 presenters for an event filled with music, art, history, and storytelling, was just the start. 2024 marks the 33rd Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series, an NPS tradition that has continued through wildfires, 20-foot snowpacks, and a temporary pandemic-driven shift to online programming.

When Eissler retired in 2016, Karen Amstutz, an NPS ranger naturalist who shares Eissler’s love of Tuolumne Meadows and Parsons, took over.

“Keeping this tradition alive, it’s the best part of my job,” Amstutz says. When she reaches out to potential presenters, even the biggest names, “people want to be part of the series and part of history in this way.”

After the summer series’ first few years, Eissler added a poetry festival and incorporated more naturalists and scientists, and over decades, Eissler and Amstutz have seen how the series affects people.

Eissler remembers the joy of two hikers who happened upon a Terry Tempest Williams talk, and a mesmerizing scene when poet David Mas Masumoto invited people to taste fresh peaches as he described links between the Yosemite watershed and his Central Valley farm. Amstutz saw an audience overcome with emotion as Mohawk seed-keeper Rowen White encouraged them to consider their connections to nature. Earlier this year, a teacher told Amstutz how the poetry festival had

Parsons Memorial Lodge is open to the public during the summer. The free Summer Series is supported by Yosemite Conservancy donors, as well as NPS and Conservancy volunteers and staff.

POET JOY HARJO speaks at the Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series in 2018.

prompted her to bring poetry readings to her school.

The inspiration goes both ways.

“The authors, musicians, and poets who come to Parsons are not just giving to the audience; they’re also receiving,” Amstutz says, citing writers who have drawn inspiration from the setting, as well as Outdoor Afro founder Rue Mapp, who was moved to tears when her son was invited to join a conversation about outdoor experiences.

This quiet corner of the high country has hosted countless moments of enthralled silence, intense joy, and conversations about, as Eissler says, “how to live on this Earth.” Today, the legacy of Parsons Lodge as a place that sparks discussions and ideas is very much alive.

“It sometimes feels magical,” Amstutz says. “I don’t use that word lightly; there’s something that happens within those walls. Maybe it’s the history, or all the voices of the people of the past lingering there.”

NOTABLE R eadings

INSPIRING AND INSPIRED, the voices of those who have enthralled visitors at Parsons Memorial Lodge are many. Eissler and Amstutz shared a few notables:

Glen Denny

Glen Denny: Yosemite in the Sixties

Camille Dungy

What to Eat, What to Drink, What to Leave for Poison

Joy Harjo

Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings

Robin Wall Kimmerer Braiding Sweetgrass

Ada Limón

You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, The Hurting Kind

Richard Nevle & Steven Nightingale

The Paradise Notebooks: 90 Miles Across the Sierra Nevada

James Prosek

James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice

Gary Snyder

Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems

Terry Tempest Williams

Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place

Fall Favorites

WHETHER YOU are shopping for loved ones this holiday season, preparing to cozy up yourself, or gearing up for a winter adventure with friends, we have you covered!

Scan here to view these items and more in our gift guide.

Yosemite Conservancy Logo Hat

Dad hats aren’t just for parents. Driftwood tan with velcro back. Sourced from a small Central Valley company just down the canyon.

$17.99

Wild Sierra Nevada

Foster observation skills and a love of nature in young children with this beautiful companion, which provides a depth of information and stunning illustrations that will engage the whole family.

$18.99

Conservancy donors receive a 20% discount with code HOLIDAY2024*

*Code valid through Jan. 31, 2025; online purchases only.

shop.yosemite.org

Conservancy & Wildlife Enamel Pins

Adorn your favorite backpack, jacket, or hat before you hit the trails with our enamel pin collection. $5–$10 each

PHOTO: © BLAKE JOHNSTON.

Klean Kanteen Water Bottle

Insulated and climate neutral? Drink it up. This 20-ounce stainless Klean Kanteen is insulated and has a loop cap.

$33.99

Half Dome Mug

Half Dome and half-caf? Hand-thrown 14-ounce ceramic mug by Deneen Pottery, a family-owned company in Minnesota and run in a 100% solar-powered facility.

$24.99

Granite Dreams: Yosemite Note Cards

Climbing and painting are inseparable in these elegant notecards from artist/climber Rhiannon Klee, who brings sublime, surreal views of Yosemite icons to life.

$16.99

Antsy Ansel

You may be familiar with Ansel Adams’ iconic black-and-white nature photographs, but do you know about the artist who created these images? Learn about his connection to nature and Yosemite in this beautiful picture book by award-winning nature writer Cindy Jenson-Elliott and award-winning collage artist Christy Hale.

$18.99

THE NEXT GENERATION

FUTURE LEADERS ADVISORY CIRCLE UPLIFTS

SUPPORTERS AND VOLUNTEER LEADERS

BY LAUREN HAUPTMAN

nsuring Yosemite will continue to thrive in the coming decades requires innovative ideas, diverse voices, and more park champions. With a prosperous park future in mind, the Conservancy created the Future Leaders Advisory Circle (FLAC), a program that invites early- and mid-career donors making leadership gifts to advise on strategic park initiatives while gaining valuable nonprofit experience.

Convened by Caitlin Allard, the Conservancy’s regional philanthropy director, FLAC has welcomed more than 20 young professionals from diverse backgrounds, industries, and perspectives since it launched in 2020. Some grew up visiting Yosemite, while others were introduced to the Sierra Nevada as adults. All share a deep love of and commitment to Yosemite. Members participate in Yosemite Conservancy Council committee meetings, share candid input with the organization’s leadership, and take part in events and projects in the park.

FLAC members, including those profiled below, have advised on annual grants to Yosemite, helped expand the Conservancy’s audiences, supported fundraising, served on volunteer work crews, and acted as organizational ambassadors.

MARJORIE KASTEN & EVAN SMOTHERS

Neither Marjorie Kasten nor Evan Smothers felt much of a connection to the outdoors growing up on the East Coast. Even so, Marjorie became “obsessed with Yosemite” in the eighth grade when she did a history project on 19th century artist Albert Bierstadt, who painted landscapes of the American West. His work had such a profound impact on her

FUTURE LEADERS ADVISORY CIRCLE (FLAC) members support trail restoration in Yosemite Valley on a park trip in 2021.

that, six years later, while on a summer math research internship in San Bernardino, California, she convinced all the other interns — including Evan — to take a weekend trip to Yosemite.

“I’ll never forget that weekend,” Marjorie says. “After so many years of looking at those paintings and then finally seeing the Valley in person, it was unforgettable.”

Marjorie later followed Evan to live and work in Northern California, where the couple developed a strong connection to the outdoors. They spent most of their free time hiking in the Sierra, eventually planning a wedding at The Ahwahnee for May 8, 2020. COVID intervened.

“We rescheduled a bunch of times and finally decided to just elope,” Marjorie says. “The day was pretty incredible. We drove up and stayed at Tenaya Lodge. We ran around the park all day taking pictures with our photographer. There was a wildfire nearby that summer, so we basically had the park to ourselves.”

With the photographer and an officiant in tow, the couple hiked to Taft Point for a sunset ceremony.

“The light refracted off the smoke from the wildfire, and it was surreal,” Evan says. “I felt a very overwhelming sense of the power of where we were at that time. I’m not an especially emotional person, but that was an exception. I can’t even put it into words.”

Marjorie, now a program manager for Airbnb, and Evan, a software engineer for Meta, moved in 2022 to Snoqualmie, Washington. They both miss being near Yosemite, but their connection to the park is stronger than ever.

Since joining FLAC, they’ve committed to being in

Yosemite at least once a year for the group’s volunteer retreat weekend.

“It’s time we try to protect,” Marjorie says.

“Being part of FLAC has made me feel more committed, as I’ve had to assess how important it is to be involved with Yosemite,” Evan says. “You have to plan and get on a plane and fly down there and then drive. You’re not gonna do it if you don’t really wanna do it. We really wanna do it.

“We have our own story of how we came to discover Yosemite, and it has become a huge part of our lives. We want to facilitate that for other people in the future. Because having something like that in your life is one of the most rewarding things you can experience.”

VISH SUBRAMANIAN

Vish Subramanian’s visits to Yosemite have always been a “big family affair”: from scrambling up boulders below Lower Yosemite Fall with his sister as kids during annual family trips, to his own son and daughter now climbing the very same boulders.

A Bay Area native, Vish went to college in Boston, then on to Asia for eight years to work in finance in Hong Kong and Singapore.

“My first year in Hong Kong was probably the first year I didn’t go to Yosemite since I was 2,” he says. “That was sad for me.”

Returning to the Bay Area in 2015, Vish and his wife, Neha, set about recreating those annual experiences in the park with their own children — including this past May when Vish hiked with his daughter and father to the top of the Mist Trail. He also started rock climbing, which has given him new ways to see the park he has always loved.

“Rock climbing has been really fascinating for me, because I’ve been able to go to a place I love and explore it in a completely different way from new vantage points than I had in the past,” he says.

Just as Vish’s experiences in the park have expanded, so has his involvement with the Conservancy, especially since he joined FLAC’s initial cohort in 2020.

“I’ve been a financial donor since 2016, and FLAC offered me another way of giving to the park in a more active capacity,” he says. “FLAC also sets me up to be part of the organization for a much longer time — for the rest of my life — because I feel much more involved and integrated. It’s another dimension of being involved in a place I really love.”

Vish, who works for crypto company FalconX, is also pleased to be able to use his own expertise and perspective to support the Conservancy’s work: Through FLAC, he has the opportunity to participate in the Conservancy Council’s finance and investment committees.

“Yosemite, to me, is a sacred place and one of the most important places in the world,” he says. “I want to ensure it’s taken care of and preserved not just for my kids, but for my kids’ kids, and so on. FLAC provides that opportunity for me to be more active in that contribution. It melds my own inspiration for the park and its preservation with my own experience. I see a really unique opportunity to combine all that together.”

ANDREW COMSTOCK

Southern California native and Salesforce Vice President Andrew Comstock needed a hobby beyond watching UCLA sporting events. So he took up hiking. His future wife, Amy Wong, suggested he might like Yosemite, but they never found the time to visit. In 2010, Amy’s parents gifted the couple with two nights at Evergreen Lodge. Amy insisted Andrew sit in the passenger seat as they entered the park.

“That first part of the drive, where you’re going by Bridalveil Fall and the Three Brothers and El Cap — I remember being fundamentally overwhelmed that such a place could exist,” he says. “We hiked to the top of Yosemite Falls, and I said: ‘This is the coolest thing I’ve ever done. We should do more of this.’”

So more they did. He started tracking his hikes in 2013 and will hit 4,000 miles this year.

Andrew first learned about the Conservancy through the magazine. An article drove him to the website, where he found giving options and donated on the spot.

“I just started donating because I loved it so much, and I spent so much time there,” he says. “I didn’t know what the Conservancy did. I didn’t know what their projects were.”

That all changed when he was invited to join FLAC in 2021.

“Yosemite feels so big, and it’s part of the federal government, which is massive in and of itself," he says. “Now I’m figuring out how I can, in my own way, have an impact on the park. FLAC is a great channel to both do the actual hands-on work and also influence the Conservancy and where they’re going.

“I just want Yosemite to continue to fire up all people for a long time — like, forever and ever and ever.”

For information about FLAC, please visit yosemite.org/flac, or contact Caitlin Allard callard@yosemite.org.

LOVE LETTERS TO YOSEMITE

Conservancy donors share stories of why they are inspired to give back to the park they love

Scan the code to read more stories, or submit your own

Layering Memories

“My family has loved visiting Yosemite ever since I was a young kid, but it was during my weeklong stay as a sixthgrader camping with my class that I fell in love with Yosemite. I was a shy, reserved kid who was not athletic and had never gone hiking before. On our first outing, my group hiked up Vernal and Nevada falls. Hiking up the Mist Trail, out of breath, and barely able to see because of the spring snowmelt coming off the waterfall, I never thought I would make it to the top. I wanted to turn around and give up! However, with the encouragement of my group and leaders, I did it! Standing at the top of Nevada Fall is a memory I have never forgotten. And every other hike and activity I did that week only grew my love and appreciation for the park and for nature, as well.

This past summer, I volunteered with Yosemite Conservancy in Mariposa Grove. I had never been to this part of the park before. But walking among the giant sequoias and learning about the human history in Wawona — especially of the Indigenous, Black, and Asian people who worked to protect the park — gave me an even deeper appreciation for Yosemite. I hope I can keep adding more and more layers to my Yosemite story for years to come.”

SATOMI FUJIKAWA Sequoia Society Member & Conservancy Volunteer

SATOMI FUJIKAWA volunteers with the Yosemite Conservancy as a visitor information assistant in Wawona.

The Connection of Visual Art to Yosemite

“It all began with my mother. Her love of the Valley and Half Dome, especially, traces back to her great-grandfather, the landscape painter Thomas Hill. Just as she was introduced to the park as a child by my grandparents during the Great Depression, she was determined that I would grow up with the same fascination and appreciation of Yosemite. On my first trip to the park as a 5-year-old in the 1950s, my impressionable mind was startled by the neck-bending geometry of the sheer towering cliffs and the roaring power of the waterfalls.

My earliest activities were focused on hikes and auto tours of the Valley floor while staying at Yosemite Lodge or Camp Curry. Each day climaxed with our viewing the famous Firefall cascading from Glacier Point; as we waited in the dark, I challenged my eyesight to locate the pinpoint of light of the smoldering embers on the cliff top.

In the summer of 1960, our family ventured out to drive the tortuous Tioga Road to Tioga Pass. I loved it, but my poor mother was a nervous wreck. To recover from this “ordeal,” we later journeyed south to Wawona and its famous hotel. My singular memory there was viewing a tall, narrow Hill painting of one of the magnificent sequoias in nearby Mariposa Grove. That same day, I saw the real things during our drive through the Wawona Tunnel Tree.

As I reached teen and college years, Yosemite and Thomas Hill’s artistry were among the greatest influences in my discovery of John Muir’s writings, my embracing of an environmental ethic, and my decision to pursue geology as a professional career. My explorations in Yosemite expanded to camping, more-challenging hikes to the rim of the Valley, backpacking in the high country, and even field trips to the park for my geology classes.

Since then, my wife and children have become fans of the park, and we are pleased to see the Park Service has recognized Thomas Hill’s art studio as its visitor center in Wawona.

A few years ago, as I was driving home along the Tioga Road after geologic fieldwork on the east side of the Sierra, I reflected on how lucky I am. The connection of visual art to Yosemite is powerful as displayed by Hill’s paintings.”

CHRIS HIGGINS Friend of Yosemite

TOP: Chris Higgins at the base of the Half Dome cables. BOTTOM: Higgins' family — his wife Jane, son Brendan, and two grandchildren — at Lower Yosemite Falls

PHOTOS: © CHRIS HIGGINS.

MEET THE TEAM:

EMILY BROSK

EMILY BROSK is an essential part of the Conservancy's volunteer programs. (Above) Brosk smiles on a solo trip out to Hetch Hetchy. (Right) Brosk speaks at a staff gathering in 2022.

PHOTOS: © (ABOVE) EMILY BROSK (RIGHT) © YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY.

Scan to learn more about our volunteer programs

EMILY BROSK, Yosemite Conservancy’s director of volunteer programs, runs a program that provides close to half a million dollars worth of labor to the park each year.

Hundreds of people come to Yosemite to assist with projects ranging from trail restoration to removing invasive plants to helping visitors navigate the park pointing them to trailheads, restrooms, and activities to match their interests and abilities. And they have a lot of fun while doing it. (Read more about our volunteer program on page 14.)

If I had to explain my job to a stranger, I’d say …

I run the volunteer program for Yosemite Conservancy — aka adult summer camp! I recruit and train hundreds of individuals to be part of a

volunteer team that either provides visitor information or participates in restoration projects in the park.

Colleagues come to me for …

Last-minute things for anyone’s project. I’ve hosted hundreds of events during my Yosemite career and specialize in creative solutions for last-minute crunches … and emergency plans! After living in Yosemite Valley from 2007 to 2019, I’ve seen a lot of different natural events dominate the landscape: fires, floods, hantavirus and plague outbreaks, rockfalls, road closures, evacuations, shelter-in-place orders.

My favorite part about my job is …

The people. My role focuses on the people who are obsessed with Yosemite — not just in love but truly obsessed to the point that being a longtime visitor isn’t enough; they want to do more for the park. I get to facilitate their dreams of living in the park and participating in park operations and resource protection.

People are surprised to learn this about me …

I was studying outdoor recreation and geology at Middle Tennessee State University — to become a state park ranger — where I happened to meet Cory Goehring, who’s now the Conservancy’s senior naturalist. A bunch of friends were hanging out on the front porch one night listening to a young couple who had just returned from working a summer season in Yosemite. They told us tales of living in Yosemite Valley and hiking in the high country, wildlife encounters, and rafting the Merced River. Prior to that, I had only seen Yosemite in books and movies.

Most of my friends took off for Yosemite as soon as they graduated — at least 10 of them! After hearing so many more stories and seeing their pictures, I knew I needed to head west for my career in public lands. It was hard to turn down the state park ranger gig I had been working toward, but I knew there were bigger rocks I needed to play with! I gave up limestone

and karst topography for life surrounded by granite and glacier-carved landscapes. Ultimately, I came to Yosemite for a seasonal job almost 18 years ago and couldn’t be happier to call this my home.

I spend my days …

With Finnegan, a super-mutt I adopted from the local SPCA this past spring. We’ve been swimming in rivers and exploring the back roads of Mariposa County. Now that I own a home in Mariposa, I’m growing a garden. The goal is to grow enough produce to support our volunteer teams who are up living in the woods and my household of furry friends! Colby, the bunny rabbit, and Tito, my sweet cat, help with rodent control and the abundance of fresh greens.

I’m inspired by …

Seeing people achieve their Yosemite goals! Working with folks through the whole process of identifying their goals, identifying risks and hazards, planning and prepping for the worst while hoping to experience the best, and then seeing their faces light up at the end of an epic experience. Giving people the opportunity to live out their dreams and passions is absolutely what inspires me to be dedicated to the volunteer program and the work I do in Yosemite.

Legacy Begins With You!

Have you ever thought about the impact of your actions on Yosemite? See if you can make good choices as you navigate up the Mist Trail steps. Each challenge station shows how choices made in the park will affect future Junior Rangers.

Stay on Trail

Following the path protects habitats (and you!) from getting hurt.

HOW TO PLAY

1. Grab a small object (a leaf, a pebble, etc.) and a die.

2. When it’s your turn, roll the die, and move along the board.

3. At Challenge Stops, roll again — even numbers mean you made a good choice and can move up 1 space; odds mean you chose poorly, and must move back 2 spaces.

4. Be careful — near the end of the trail is the Search and Rescue Square. Land here, and Search and Rescue rangers will have to help you back to the beginning to try again.

5. Everyone wins when the whole group makes it safely to the top of the waterfall.

Take Only Pictures

Plants that grow along trails are protected in national parks. Take pictures, don’t pick wildflowers.

Respect Wildlife

Stay a safe distance from wildlife, and never share your snacks — no matter how much they ask.

Be Prepared

Make sure you are trail ready: snacks, water, shoes, layers, and sun safety.

Junior Ranger

YOSEMITE THROUGH YOUR LENS

Park fans share their photos of Yosemite

Misty Mood

© MICHAEL KLIMAS.

Autumn Splendor in Cook's Meadow

© DAN KURTZMAN PHOTOGRAPHY.

PeekABoo

© ROSS CUMMINGS.

Daydreaming of Half Dome

© ADVENTURE TRAMP.

Thanks for sharing your shots, Yosemite fans!

To see more photos of the park, and share your own, follow @yosemiteconservancy on social media:

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL MEMBERS

CHAIR

Steve Ciesinski*

VICE CHAIR

Dana Dornsife*

SECRETARY

Robyn Miller*

TREASURER

Jewell Engstrom*

PRESIDENT & CEO

Frank Dean*

COUNCIL

Hollis & Matt* Adams

Gretchen Augustyn

David & Amelia Cameron

Jessica* & Darwin Chen

Diane & Steve* Ciesinski

Kira & Craig Cooper

Hal Cranston & Vicki Baker

John & Meredith Cranston

Carol* & Manny Diaz

Leslie & John Dorman

Dana* & Dave* Dornsife

Jewell* & Bob Engstrom

Kathy Fairbanks

Sandra & Bernard Fischbach

Cynthia & Bill Floyd

Bonnie Gregory

Rusty Gregory

Laura Hattendorf & Andy Kau

Christy & Chuck Holloway

Christina Hurn

Mitsu Iwasaki

Erin & Jeff Lager

Bob & Melody Lind

Patsy & Tim Marshall

Kirsten & Dan Miks

Robyn* & Joe Miller

Juan Sánchez Muñoz* & Zenaida Aguirre-Muñoz

Kate & Ryan* Myers

Daniel Paramés

Sharon & Phil* Pillsbury

Gisele & Lawson* Rankin

Bill Reller

Pam & Rod* Rempt

Skip Rhodes

Alain Rodriguez* & Blerina Aliaj

Dave Rossetti* & Jan Avent*

Greg* & Lisa Stanger

Ann* & George Sundby

Alexis & Assad Waathiq

Clifford J. Walker

Wally Wallner & Jill Appenzeller

Helen & Scott* Witter

*Indicates Board of Trustees

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK

Superintendent Cicely Muldoon

Ways to Give

There are many ways you and your organization can support the meaningful work of Yosemite Conservancy. We look forward to exploring these philanthropic opportunities with you.

CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER

Marion Ingersoll mingersoll@yosemite.org 415-362-1464

LEADERSHIP GIFTS – NORTHERN CALIFORNIA & NATIONAL

Caitlin Allard callard@yosemite.org 415-989-2848

LEADERSHIP GIFTS –SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

Julia Hejl jhejl@yosemite.org 323-217-4780

PLANNED GIVING & BEQUESTS Catelyn Spencer cspencer@yosemite.org 415-891-1039

Contact Us

VISIT yosemite.org

EMAIL info@yosemite.org

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

ANNUAL, HONOR, & MEMORIAL GIVING Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemite.org 415-891-2216

MONTHLY GIVING Cailan Ackerman sequoia@yosemite.org 415-966-5252

GIFTS OF STOCK Eryn Roberts stock@yosemite.org 415-891-1383

FOUNDATIONS & CORPORATIONS Laurie Peterson lpeterson@yosemite.org 415-906-1016

PHONE

415-434-1782 MAIL

Yosemite Conservancy 101 Montgomery Street, Suite 2450 San Francisco, CA 94104

Magazine of Yosemite Conservancy, published twice a year.

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren Hauptman

DESIGN

Eric Ball Design

JUNIOR RANGER ILLUSTRATOR

Lou Zabala

Autumn Winter 2024 Volume 15 Issue 02 ©2024 Federal Tax Identification No. 94-3058041

LEADERSHIP

Frank Dean, President & CEO

Kevin Gay, Chief Financial Officer

Marion Ingersoll, Chief Development Officer

Kimiko Martinez, Chief Marketing & Communications Officer

Adonia Ripple, Chief of Yosemite Operations

Schuyler Greenleaf, Chief of Projects

For a full list of staff, visit yosemite.org/staff

For a full list of our 2024 grants, visit yosemite.org/impact

YOUR Yosemite Legacy

WHEN YOU include Yosemite Conservancy in your will or trust, or as a beneficiary of your retirement account, you create a legacy that will protect this amazing place for generations to come.

Your gift becomes part of the legacy fund, which makes meaningful work possible and sustains programs that will benefit visitors well into the future. It is a wonderful way to commemorate your special memories in Yosemite National Park, while also ensuring future generations will be able to create memories of their own.

To learn more about a legacy for Yosemite, please contact Catelyn Spencer at cspencer@yosemite.org or 415.891.1039.

yosemite.org/legacy