IN YOSEMITE, scale is a matter of perspective. We’re awed by the big: granite walls glowing at sunrise, lakes framed by peaks, the sweep of dedicated conservation work. But spend enough time here, and you realize the small things can carry great weight.

This issue celebrates that interplay of big and small. You’ll read about research that reframes millions of years of geologic history — and revitalizes a modest stone hut at Glacier Point. You’ll see how nearly two decades of steady work transformed Tenaya Lake’s fragile shoreline into a haven for people and wildlife. You’ll witness how a single match, in the hands of Tribal stewards, can restore the health of a forest and the culture of a community. And you’ll meet the lichen, fungi, and other overlooked wonders that quietly sustain Yosemite’s ecosystems.

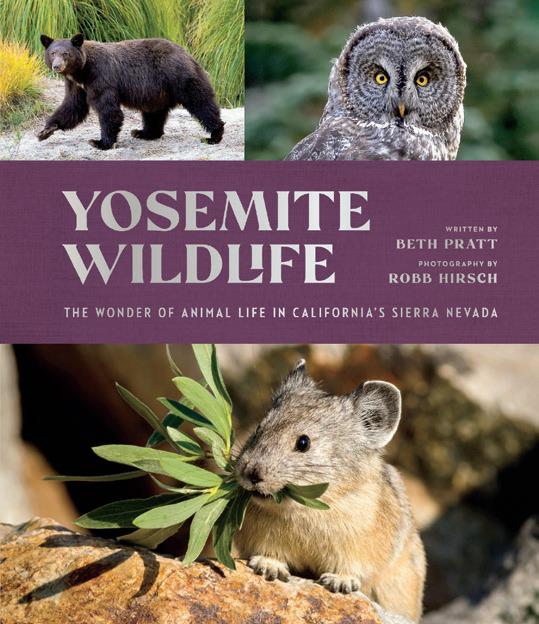

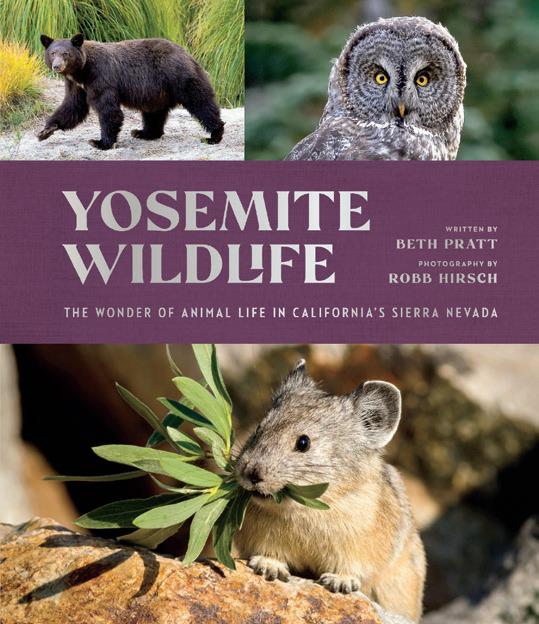

We’re also celebrating something both grand and intimate: the first comprehensive Yosemite Wildlife book in more than a century. It’s a hefty volume, yet within its pages, the smallest pollinator shares equal importance with the largest mammal, reminding us that Yosemite’s story is written by all its inhabitants.

In philanthropy — just like in nature — small things can have a big impact. A modest gift, a few volunteer hours, a heartfelt conversation … each one can shape Yosemite’s future. Your generosity protects the sweeping landscapes and the most delicate life-forms alike.

Here’s to seeing it all — and to valuing it all.

With gratitude,

Cassius M. Cash PRESIDENT & CEO

From lichen to fungi to tiny wildflowers, Yosemite Conservancy naturalists reveal how small life-forms are essential to the park’s grand landscapes. PAGE 4

Breakthrough research is rewriting the Valley’s geologic history and giving new life to a century-old hut at Glacier Point. PAGE 14

A Tribally led project is reviving cultural burning in Yosemite, healing the land, as well as the relationship between people and fire. PAGE 8

Meet Yosemite’s small, firetruck-colored amphibians in this excerpt from the recently released Yosemite Wildlife book. PAGE 12

18 years of steady improvements — from trails to revegetation — have revitalized this iconic alpine lake. PAGE 20

Join these skilled travelers through an adventurous excerpt from the recently released Yosemite Wildlife book. PAGE 24

As regional philanthropy director for Southern California, Julia pairs donor passions with projects to make a lasting difference in Yosemite. PAGE 26

From big summer meadows to small winter burrows, pikas show how life in Yosemite changes with the seasons. PAGE 28

Park fans share their photos of Yosemite. PAGE 30

OUR MISSION Yosemite Conservancy inspires people to support projects and programs that preserve Yosemite and enrich the visitor experience for all.

BY LAUREN HAUPTMAN

t’s easy to think everything in Yosemite is about the big: the world’s largest granite monolith, some of the world’s largest trees, and one of North America’s largest waterfalls. But what excites many naturalists about the park are the little things of Yosemite. Like countless visitors, these naturalists came for the big, but what keeps them here is the little.

Yosemite Conservancy’s Outdoor Programs Manager and Senior Naturalist Cory Goehring loves lichen. Goehring’s wife loves lichen. Goehring’s son’s middle name is Lichen. His wife suggested the name, explaining their child represents the symbiotic relationship between them, just as lichen represents the symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae. In fact, the word symbiosis was created in the 1800s to describe lichen.

With more than 500 different species of lichen in Yosemite, you’ll see them everywhere — once you start looking.

“Lichen are one of those little things people overlook,” says Goehring, a self-described lichen evangelist. “But as famous Yosemite naturalist Carl Sharsmith said, ‘The more you know, the more you see.’ Once you know, you’ll notice them everywhere, and they’re so beautiful. They come in the darker blacks on the cliffs of Yosemite, but if you

look closely, you’ll also see these vibrant greens and almost psychedelic-looking oranges on the rocks that are all lichen.”

Lichen often look like a simple patch of crust, fuzz, or leafy growth on a rock or tree, but they’re actually a remarkable team effort between two very different organisms: a fungus and a photosynthesizing partner such as algae. The fungus provides a sturdy structure where the algae can live, shielded from harsh weather. In return for living inside the fungi’s structure, the algae use sunlight to make food for the fungus that the fungus can’t produce on its own. This partnership benefits both organisms and allows lichen to survive in places few other life-forms can live.

Lichen are excellent indicators of air quality. They are sensitive to air pollution, because everything they need to exist comes from air and sunlight, which photosynthesizes with water. If you see lichen in the area, it’s a good bet the air quality is good, so take a deep breath.

Lichen are also considered a pioneer species. A fresh rockfall won’t have lichen, but one that has been there for several decades or much longer will likely have a patina of lichen that grows over it. Once that patina covers rocks or cliffs, it can serve as an anchor for other things to live on the surface — dust and pollen particles, spiders and other small creatures, and so on.

Adventurers, too, like to explore where the lichen live. It’s easy to look at a popular route — say, Half Dome from the Yosemite Conservancy spotting scope at Olmsted Point — and see where climbers and cables have worn away a path in the lichen patina. It’s yet another reason to adhere to Leave No Trace principles in alpine areas. By being mindful of where we tread, we give lichen and other sensitive alpine species a greater chance of survival.

Way before dinosaurs, way before sequoias, way before the earliest mammals, there were fungi — one of the two parts of lichen. Fungi play vital roles in our lives, as well as the life of the park. They aid decomposition, breaking down everything from bananas to big-leaf maple leaves.

“One of the things people don’t know about fungus is that it’s not a plant,” says Dan Webster, a naturalist who leads a fungifocused Yosemite Conservancy Field School program each year. “And when you see the bright red, beautiful mushroom growing out of the ground, it’s only a small part of the fungal body — just the fruiting part. The rest of the fungal body is deep inside a dead and decaying tree, or way, way underground. It just pops up a fruiting body so it can release spores to reproduce.”

There are many dozens of species of fungi in Yosemite — from those underground to those on trees to those in microhabitats on the Valley cliffs.

“As fungi spreads their mycelium — a root-like structure through which a fungus absorbs nutrients from its environment — out underground, they’re in search of food,” Webster explains. “Fungus grows into its food, then enzymatically breaks it down and absorbs it, often by creating a symbiotic relationship with tree roots and plant roots.”

Some 90% of the world’s plants have a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Tree roots and root hairs are covered with mycelium, which is composed of thread-like filaments that greatly extend the reach of roots, allowing the tree to gain more water and nutrients than it would by itself, all the while feeding the fungi.

The list of Yosemite’s little organisms is seemingly endless: alpine butterflies, tiny wildflowers, elusive salamanders, countless species of bees, lichen, fungi, moss … all these petite parts are essential members of the park’s ecosystems.

Single drops of water froze to form the glaciers that sculpted this area, Goehring adds.

“Even those pesky mosquitoes we curse throughout the summer are feeding bats and helping pollinate some of the flowers,” he says. “The lichen that are breaking down the rocks are feeding 1,600 different vascular plants that are here in the park. It’s all interconnected, and if you take away one small little thing, it can mess up the entire ecosystem.”

Yosemite Conservancy donors appreciate the importance of every single species and are passionate about funding projects ranging from big wall bats to studying monkeyflowers on the side of a cliff to teaching visitors about the importance of tiny pollinators. Donors, too, are part of the interconnectedness of the park.

“People can look at Half Dome or El Capitan or giant sequoia trees, and it’s so easy to feel that sense of awe and wonder,” Webster says. “But the opportunity for awe and wonder is not limited. These smaller things can be found in many, many, many places, and once we develop wonder about them, we get that sense of that awe everywhere.”

“Yosemite is a living puzzle, and our donors ensure no piece ever goes missing. Their support helps protect the big picture by safeguarding every little piece.”

Cory Goehring SENIOR NATURALIST

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

To learn a little bit more about the big picture of Yosemite, join a Yosemite Field School program. Our expert-led courses piece together the story of the park — from the grand landscapes to the smallest details.

Scan to find your course

BY KIMIKO MARTINEZ

quiet transformation is underway in Yosemite Valley — one that promises to restore not just the landscape, but the deep-rooted relationship between people and fire.

The “Little Fires” project, a Tribally driven, multiyear initiative funded by Yosemite Conservancy donors, is reintroducing cultural burning practices to the park. Using the same traditions and techniques that Native people used to tend these lands for millennia, Little Fires will focus on small areas with low-intensity fire.

Though it’s starting as a pilot program, project leaders hope it creates a foundation for a lasting paradigm shift.

“For over a century, we’ve suppressed fire; but fire is the Sierra Nevada’s natural recycling mechanism,” explains Garrett Dickman, a forest ecologist and National Park Service branch lead for vegetation and ecological restoration in Yosemite National Park. “Without it, dead material has stacked up like tinder. In the most fuel-loaded locations, it can get to be so much, it’s like the equivalent of stacking six [Boeing] 737s. It’s just energy waiting to burn.”

The consequences have been catastrophic: high-severity

wildfires that devastate forests, destroy wildlife habitat, and threaten communities. But Little Fires takes a different approach. It centers Native knowledge and leadership, placing crews from local Tribes — people whose ancestors have spent millennia tending these lands — at the heart of forest stewardship. Rather than viewing fire as a threat, these teams are trained to wield it as a tool of care — clearing fuels, reviving traditional plants, and healing the land.

“This isn’t just restoration of the land; it’s restoration of the people,” Dickman says. “That relationship between land and people, with fire as the connecting thread, has been here since time immemorial.”

Irene Vasquez, a Southern Sierra Miwuk Tribal member and cultural biologist formerly with Yosemite National Park and now with the Great Basin Institute, puts it more personally: “Fire is good for us — our hearts, our health, our food. It’s spiritual, physical, cultural. These plants evolved with people. And people evolved with fire.”

Vasquez notes the long history of Native people tending to the plants and the critical use of fire to cultivate foods and strengthen crops, such as acorns, on which local

animals rely. Fire, she says, is “needed to make food healthy again. To make us all — humans and our non-human relatives — healthy again. And to remind us that people are part of this landscape, too.”

For Tribal communities, fire is not only ecological, but deeply cultural. Many species — such as black oaks, willow, and deer grass — depend on regular, low-intensity burns to thrive. Those burns, in turn, support traditional foodways, medicine, basket-making materials, and ceremonies.

“This is the kind of burning we don’t normally do in Yosemite,” Vasquez explains. “We don’t burn to reduce acorn pests. We don’t burn to renew straight willow shoots for baskets. But now, we can.”

What makes Little Fires different is the structure: Tribal crews aren’t just participating; they’re leading. While federal compliance still applies, the program is designed to reduce bureaucratic delays and place decisionmaking power in Native hands.

As Dickman notes: “We’re not trying to run a project. We’re building a program. And in time, we want it to be fully Tribally led.” That leadership includes more than just technical training. It’s about restoring generational knowledge and connection.

“People used to have fire every day — cook fires, ceremonial fires. We lived with fire,” Vasquez says. “This is about regenerating that relationship, not just for us, but for future generations.”

It’s an issue she thinks more about since she became a mother. “I used to do this cultural work for my grandma and my elders,” says Vasquez,

“This is about regenerating that relationship [with fire], not just for us, but for future generations.”

Irene Vasquez, SOUTHERN MIWUK TRIBAL MEMEBER

whose son was born in 2023. “But now it’s shifted. Now I’m thinking more about the future generations, and it gives me more reason to keep it going.”

The work isn’t quick or easy. Fire suppression during the past century created a dangerous backlog of fuel. Healing will take time — decades, maybe more.

“It’s like peeling back layers,” Dickman says. “We start with needles and sticks, then branches, then logs. Some places need heavy machinery. But everywhere else, we’ll use fire.”

And fire, when used responsibly, gives back.

“We’re finally meeting our mission — restoring natural and cultural resources, unimpaired, for future generations,” Vasquez says.

Perhaps most importantly, Little Fires reflects a larger shift: away from a one-size-fits-all approach to fire management, and toward one rooted in place, people, and long-standing knowledge.

“Fire looks different everywhere,” Dickman says. “Yosemite fires aren’t Southern California fires.”

Vasquez agrees. “Cultural fire isn’t wildfire,” she says. “It’s tended. It’s intentional. It’s medicine.”

As Tribal crews began their fieldwork late this summer, and the first cultural burns in two decades start this fall, a new narrative is taking hold in Yosemite — one where fire is not just a force to fear, but a partner in healing. Not just a tool of destruction, but of renewal.

Gift an unforgettable experience that supports the park you love.

From stargazing programs and guided hikes to watercolor workshops, Yosemite Conservancy’s expert-led experiences will deepen your loved one’s connection to the park — and help preserve it for future generations.

Looking for a great digital gift that doesn’t require shipping? Get your gift card now for the 2026 season!

Enjoy this excerpt about one of Yosemite’s small creatures from Yosemite Conservancy’s new legacy publication, Yosemite Wildlife by Beth Pratt, photography by Robb Hirsch. A companion piece is featured on page 24.

he first heavy rain in January in the Sierra foothills usually marks the beginning of a wonderous time: newt season! The morning after each rainfall, I excitedly dash to the Merced River, ready for seasonal newt patrol. Even being cold and wet and kneeling in mud cannot diminish my joy of watching the annual “commute of the newts.” These small amphibians the color of a firetruck amble on outsized webbed feet with the rhythm and motions of a child’s wind-up toy. As they awaken from their winter slumber and walk down the river canyon to their breeding ponds, their paw-like toes move at a slow, methodical pace. These purposeful travelers connect me to the patient clock of nature, one attuned to geologic time; these paths along the Merced River are likely the same trails the newts have followed for thousands of years. Research has shown these long-lived newts, who can reach up to even 40 years of age, return generation after generation to the ancestral ponds of their birth to breed. How do they navigate each year from their winter retreat, sometimes miles away, to the newt version of the singles bars to find a mate? Newts possess incredible navigational abilities, talents we don’t yet fully understand.

As journalist Kathryn Schulz wrote, nothing we humans possess “enables us to navigate even half as well as a newt.” What we have learned, however, is remarkable. Newts are thought to navigate partially from a sense of smell; the odor of their birth pond is imprinted upon them. Herpetologist Robert Stebbins observed seeing a California newt leave what he considered a series of odorous breadcrumbs, “droplets of fluid exuding from the vents of California newts as they make their way along their migratory routes.” Other studies have shown that newts employ visual cues, such as rocks or trees, and they even gaze at the stars to help with their wayfinding.

When they arrive at their ponds to trade their winter terrestrial existence for months in the water, the males wait for the females. During this anticipatory period, males are at their most charming: they swim quickly to the surface when I arrive (perhaps thinking me a prospective date), and at times they dart to the top and then hang suspended with their head at the surface, endearingly blowing bubbles. When the females eventually arrive, the newt version of WrestleMania begins, the ponds serving as the ring. Multiple males often try to secure a female, and this competition creates wriggling balls of tussling newts as they float underwater — a marvelous spectacle of unsynchronized swimming … Yosemite cultural ecologist, Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation member, and my friend, Irene Vasquez intimately knows the rhythms and cycles of the natural world in our area. She also knows of my passionate advocacy and affinity for newts, and she shared with me a story to give me hope after I had been despairing of finding newts mushed by bike tires. “I thought of you when I was reading this research,” she related to me over the phone. “I’ll send it to you.” The research was a section from the 1967 ethnological notes by C. Hart Merriam that says that the water dog “with red or orange belly … common in streams and pools … [was] among the First People … a powerful chief. Every time you kill one it will rain.” So, to save a newt, and to spare the wrath of a mighty animal lord, follow the advice of the sign we erected at the start of the risky proposed [mountain bike] trail location along the Merced River: “Slow down for newts!”

Curious about other small creatures who call Yosemite home?

Read this and more only-in-Yosemite stories in the new Yosemite Wildlife book, available at shop.Yosemite.org or wherever books are sold.

Breakthrough research is rewriting the Valley’s geologic history and giving new life to a century-old hut on Glacier Point

BY ZOE DUERKSEN-SALM

igh above Yosemite Valley, a small stone hut sits peacefully among the trees on the edge of Glacier Point. At first glance, the Geology Hut is quite unassuming, with its stone walls and timber roof that mimic the natural architecture of the surrounding landscape.

Once inside the hut’s century-old walls, however, you’ll begin to understand its purpose. Exhibits teach visitors about Yosemite’s geologic history and importance, and through the hut’s large arched windows, these geologic wonders can be observed with inquisitive eyes.

Yosemite Valley stretches below. To the east, the Valley splits in two: The southern Merced River Corridor showcases cascading waterfalls and remnants of Yosemite’s historical glaciers, while the northern Tenaya Canyon carves a path between Mount Watkins and Clouds Rest.

As permanent and grand as this view feels, the truth is that long ago — before the Geology Hut was built as the National Park Service’s first “Trailside Museum” in 1925, before the designation of Yosemite National Park in 1890, and even before people inhabited this land — these marvelous valleys and canyons didn’t exist.

Previous age estimates for Yosemite Valley ranged from 3 million to more than 50 million years old. Some geologists hypothesized the canyon must be as old as the long-standing Sierra Nevada range, while others thought the shape of the Valley suggested it was created by glaciation much more recently.

“There are some ideas that Yosemite Valley is tens of millions of years old, and I’ve always had some trouble with that,” says park geologist Greg Stock, who has lived and worked in Yosemite for nearly 20 years. “The steep Valley walls are composed of fresh-looking granite that experiences rockfalls every few days. To me, that suggests a youthful landscape.”

It wasn’t until the late 2000s that a new canyon-dating technique was developed, finally allowing geologists to determine a more precise age estimate for the view from Glacier Point.

The method — known as helium-4/helium-3 thermochronometry — relies on a simple principle: Rocks are hotter the deeper they are underground, and they cool as erosion strips away overlying layers. These temperature

changes leave a measurable record of helium trapped within the rock minerals. By analyzing that record, researchers can reconstruct the temperature history of a rock and approximate the time when the rock was carved and exposed.

In 2010, glaciology professor and researcher Kurt Cuffey from the University of California, Berkeley, joined forces with Stock and others to apply this new technique in Yosemite. While they couldn’t date Yosemite Valley itself — because the Valley’s rock bottom is unreachable at 2,000 feet under a sandy floor — they were able to date the adjacent Tenaya Canyon, which, given its close geological ties to the Valley, is likely around the same age.

“Yosemite is a spectacular place, but geologists have never been able to rigorously pin down when the canyon was formed,” Cuffey says. “Until our study, it was all just assumptions.”

The team compared granite from the canyon’s rim with granite from its floor. The upland rocks revealed long-stable, cool temperatures, indicating that the high plateau has remained largely unchanged for tens of millions of years. But the canyon-floor rocks revealed a very different story: they were still warm about 10 million years ago, then cooled rapidly between 10 million and 5 million years ago — evidence that Tenaya Canyon was carved deeply during that window of time.

In 2023, after years of modeling and analysis, Cuffey

and his team published their findings: Tenaya Canyon is geologically young, with an estimated age of only 5 million to 10 million years.

“Five million years seems like a really long time, but in the context of an Earth that is 4.5 billion years old, that’s just a tiny, tiny fraction of time,” Stock says.

Given these younger estimates, Cuffey and Stock believe the area was once a shallow valley. Then, 5 million to 10 million years ago, a river began to slice into the canyon floor and initiate the carving of Tenaya Canyon. A couple million years later — likely 2 million to 3 million years ago — the climate cooled, and glaciers came down through Tenaya Canyon into Yosemite Valley. These glaciers further sculpted the canyon walls and reshaped the landscape into what we see today, including Yosemite’s iconic peaks and monoliths.

One of these iconic spots, Glacier Point, has given pause to scientists for centuries. Looking down on Yosemite’s deep canyons, the mind questions how and when such a marvelous feature formed ... it’s no wonder that Cuffey and Stock spent the past two decades researching just that.

The overlook sparked such awe that early scientists wanted to share these ideas with the public by building the Geology Hut, which was funded by the Yosemite Natural History Association — now Yosemite Conservancy.

Cuffey and Stock, alongside granite specialist Allen Glazner and others, are continuing this work by revitalizing the 100-year-old Geology Hut’s informational panels with updated scientific knowledge, including their recent geologic findings.

“The old displays in the hut were in serious need of updating since the science has progressed so much over the past several decades,” Stock says. “Development of the new displays is also coinciding with the rehabbing of the hut itself … remortaring the stones, replacing the roof and beams. The combined projects will revitalize one of Yosemite’s most beautiful sites.”

The project builds on the hut’s long history of using interpretive displays for visitor education and is made possible, in part, by Conservancy donors. One of the

project’s biggest donors, UC Berkeley adjunct faculty member Nadine Tang, found her way to funding the hut through auditing one of Cuffey’s geomorphology courses, in which he highlights his work in Tenaya Canyon and the joys of exploring geologic landscapes.

“While I have always been awed by the beauty of nature and landscapes, it wasn’t until I got to know Kurt Cuffey that I became curious about how these landscapes were formed,” Tang says. “It is my hope that the new Glacier Hut elements will enrich the experiences of those fortunate enough to set eyes on it.”

Those who look inside and outside the Geology Hut are not just witnessing the grandeur of Yosemite; they’re looking into a geologic story that’s still unfolding. Thanks to the passion of researchers and supporters alike, this small stone hut continues to invite big questions, spark curiosity, and deepen our understanding of one of Earth’s most aweinspiring landscapes.

SO SMALL

THIS HOLIDAY SEASON, celebrate your love for Yosemite with gifts — big and small — for little explorers and seasoned adventurers. Whether you’re shopping for family, friends, or yourself, we’ve got you covered!

Conservancy donors receive a 20% discount with code HOLIDAY2025*

*Code valid through Jan. 31, 2026; online purchases only.

Scan here to view these items and more!

shop.yosemite.org

Yosemite Wildlife

Yosemite is more than scenic vistas — it’s home to a remarkable wild animal world. Written by Beth Pratt with photography by Robb Hirsch, this 456-page volume is the first comprehensive book on Yosemite’s wildlife in over 100 years. It showcases 150+ species with 300+ stunning images, rewilding success stories, scientist profiles, and more.

$60.00

So Big! Bundle

This set comes with the So Big! book and a bear plush. Journey through Yosemite’s iconic wonders — Yosemite Falls, Half Dome, El Capitan, and Tuolumne Meadows — with a whimsical bear and squirrel as guides, helping children feel at home in the park’s grand scale.

$27.00

Yosemite Conservancy Logo Wax Hat Sustainable looks good on you! Blue with strapback and metal adjuster. Organic cotton ripstop, drywax finish, cork–bamboo brim. Plastic-free.

$42.00

Klean Kanteen

Plastic-free and adventure-ready. 20 oz insulated stainless steel bottle with metal–bamboo loop lid. Made from 90% postconsumer recycled steel. Keeps drinks hot or cold on the go.

$37.99

Tuolumne Meadows Bandana

Bright orange like a Sierra sunset. Original art by Hanna Hedstrom celebrates Tuolumne’s sweeping alpine meadows. 100% organic cotton.

$19.99

This set comes with the So Small! book and a plush chickaree. Follow a bear and a chickaree as they explore Yosemite’s tiniest wonders — from a wee frog to a teeny sequoia cone — and learn that even big animals feel small in this vast park.

$17.00

BY PETE BARTELME

18 years of major improvements to trails, habitat, and visitor amenities have revitalized Tenaya Lake

he grinding power of ancient glaciers burnished the granite around Tenaya Lake into smooth domes and peaks, framing the alpine lake’s sapphire waters into one of the most beautiful and accessible spots in Yosemite National Park.

This shimmering lake has also suffered from overuse and erosion. With crowds came packed parking lots and vault toilets that took some of the shine off this remarkable gem. But thanks to the determination of those who love this place, including Yosemite Conservancy donors, many of these problems have been solved.

“What happened at Tenaya is a model of how people can come together to preserve the places they cherish,” said Yosemite Trails Work Supervisor Steve Lynds, who led a series of projects to create a full Tenaya Lake Loop Trail that improves habitat protection and the visitor experience in this area.

Tenaya Lake’s story is one of endurance and love. It begins with its special geology. The lake itself is at an altitude of more than 8,100 feet, feeding a stream that cascades down Tenaya Canyon and into Mirror Lake. Granite peaks rise more than 2,000 feet above, their flanks smooth from cycles of glaciation and thaws.

Over the years, more and more people flocked to the lake’s sandy shores along

Tioga Road. Some sat in silence, watching clouds drift overhead or climbers inch up nearby domes; others hiked along forested trails or ventured into the cold and clear water to swim, paddleboard, and kayak. A campground was established on the west shore for summer visitors, and in the winter, when conditions were just right, you could lace up skates and fly across ice.

The lake’s popularity took a toll. Heavily used trails created erosion issues in wetlands. Parking areas covered fragile habitat and marred views. Traffic flows created unsafe conditions.

In 2007, the National Park Service launched a multiyear environmental assessment concluding that nearly 10 acres around the lake needed to be restored to reinstate natural habitat and improve visitor enjoyment and safety in the area.

Leslie and John Dorman are longtime Yosemite Conservancy Board and Council members and were involved in the project’s early planning.

“It’s an iconic spot, yet it was obvious the site was really degraded,” Leslie says. “There was consensus that comprehensive work needed to be done all around the lake. In the end, it’s exciting to see what partnerships can accomplish.”

The final vision would unfold gradually — and intentionally. With an estimated cost of nearly $2 million, the project called for a series of phased efforts that would ultimately repair the landscape while improving visitor access and safety.

Over the next 18 years, Yosemite Conservancy donors, along with matching funds from the Federal Highway Administration, helped bring that vision to life by funding work carried out by National Park Service crews and Yosemite Ancestral Stewards (YAS), a local Tribal crew that protects and preserves the park’s cultural and natural resources.

“This project was a slow but powerful burn,” says Schuyler Greenleaf, chief of projects at Yosemite Conservancy.

“We split the work into bite-size pieces, starting with the East Beach restoration in 2012, and tackled one project nearly every year after that. The final piece was connecting the Tenaya Lake Loop Trail and revegetating the area, which finished up in 2025. I love that the project was intentional and took time!”

Now, nearly three miles of trails with jaw-dropping views of the lake and granite are realigned to avoid sensitive natural and cultural resources. Signage makes it easier to find

trailheads, picnic spots, and parking areas. Pedestrian bridges and boardwalks guide hikers over waterways and wetlands to protect habitat. About 10 acres of habitat have been restored to natural conditions. Reconfigured parking for 230 vehicles protects trees and reduces the number of cars visible from the area’s viewpoints. New crosswalks and traffic-calming devices slow motorists from 35 to 25 miles per hour.

This year, finishing touches were made to the Murphy Creek area of the Tenaya Loop Trail to protect the sensitive shoreline habitat. A place that was once a parking lot with a vault toilet is now a restored riparian habitat with a loop trail that includes boardwalks to protect the surrounding wetlands. There’s an improved picnic area, accessible vault toilet, and a more efficient parking lot. During the past two summers, crews planted more than 4,000 native flora in this area as part of the restoration.

For Irene Vasquez, a Southern Sierra Miwuk Tribal member and cultural biologist — formerly with Yosemite National Park and now with the Great Basin Institute — who works with the YAS program, the work has special

meaning. Since 2020, she has led the revegetation of areas around the lake, seeking advice from Tribal elders on cultural matters and working with more than 100 local Tribal members, ages 18 to 30, from YAS crews.

“The lake is a sacred spot. Our crews live here, want to be here, and care about their homeland,” Vasquez says. “You can see that working at Tenaya inspires contentment and a positive feeling about the world. To see the Murphy Creek area returned to a more natural state at the water’s edge is a privilege.”

Another example of improvements is at the lake’s East Beach. This effort relocated a trail from the parking lot to the beach, so it no longer bisects a fragile wetland; reintroduced native willows and other wetland plants for better soil protection; and restored picnic areas, including the addition of a long communal table perfect for larger gatherings. The East Beach trail, which is wheelchairaccessible, includes educational signage highlighting Tenaya Lake’s sensitive ecology, history, and trail systems.

“I’m excited to teach my son about Tenaya’s history and spirituality, and what was done to protect the lake,” Vasquez says. “That’s a joyful experience I wish for the next generation and the ones after that.”

2007 Comprehensive, multiyear assessment of Tenaya Lake area

2012 East Beach rehabilitation

2013 Trail upgrades along the lake’s southern edge

2016 New accessible trail and boardwalk on the west end

2021 New wayfinding and informational signage

2025 Completion of Tenaya Lake Loop Trail

Enjoy this excerpt about one of Yosemite’s big creatures from Yosemite Conservancy’s new legacy publication, Yosemite Wildlife by Beth Pratt, photography by Robb Hirsch. A companion piece is featured on page 12.

ule deer in Yosemite are nomads, wanderers who journey on ancient paths, their routes passed down generation after generation in a landscape of memory from mother to offspring, the ultimate maternal gift of survival. These skilled travelers shift from the snow-covered passes to the forested and shrub-filled lowlands on an annual migration. Although some of the lower-elevation dwellers remain residents year-round, for most mule deer in the park, movement is life. They spend their days seeking out food, following the “green wave” brought on by the changing of the seasons.

Schooled as a child on epic nature documentaries that showcased herds of animals dashing, seemingly blindly, across vast plains in a competition for food, I held a preconception that migration was nature’s great race. But it’s not. There is no endgame — no final destination or ultimate winners. Instead, the journey itself is the thing, the essential purpose. As nature writer David Quammen shared: “Animal migration is a phenomenon far grander and more patterned than animal movement. It represents collective travel with long-deferred rewards. It suggests premeditation and epic willfulness.”…

Biologist Katie Rodriguez … has studied many animals in Yosemite and the Sierra and is working to build a wildlife crossing to preserve a historical deer migration route on the east side of the Sierra on Highway 395 near Mammoth Lakes. Deer traveling from Yosemite may someday avoid death by car by using

this crossing. “They’re master conquerors of the mountains,” she says. “They’ve maintained these paths for thousands of years. And a road doesn’t stop them, [or] avalanches or other weather situations. They are just hard driven to continue moving in those same migration paths.”… How do deer truly choose their seasonal pathways on the land? Perhaps the answer will remain elusive, the deer’s behavior mysterious. …

Yet I can’t help but try. When I wander in the High Sierra, I often follow deer trails, and sometimes deer join me on my travels. One summer as I searched for migrating butterflies at 11,000 feet, below Sharsmith Peak, three healthy and alert does on a nearby ridge thrust their necks toward the sky when they noticed my presence, considering me for a few minutes. After determining I was no threat, they descended to the meadow where I looked for a butterfly sign. Nibbling on lupine, they became my unintentional research assistants, flushing out some butterflies as they ate.

When I departed, I followed the path up that they had taken down, trying my hand at navigating as an ungulate, even though most of the trail was invisible to my eyes. How many years did this route stretch back?

To the deer’s mother? Grandmother? Great-grandmother? Some of these routes are ancient, thousands of years old, handed down through multiple generations. I trust their navigation skills better than I do those of humans. Some trails are faint, and they start or end with no warning — at least to my senses. I tried to think like a deer, recalling what longtime park historian Jim Snyder told me about the philosophy he followed in his trail-building days, a philosophy he had learned from Gabriel Sovulewski, who served as assistant superintendent of Yosemite from 1906 to 1936: “If the deer won’t use it, there’s something wrong with it.”

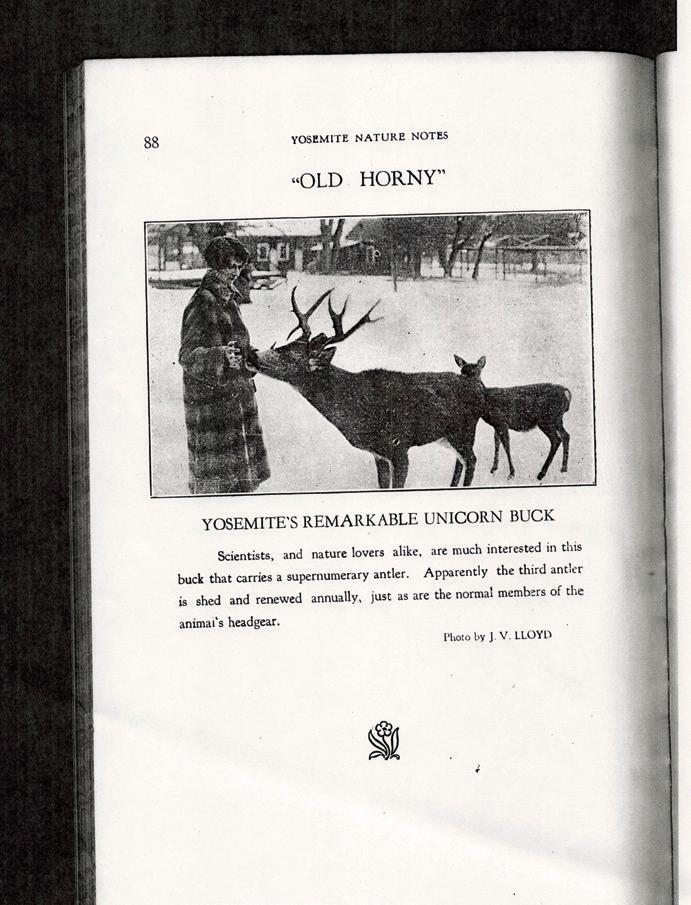

“Where is ‘Old Horny’ in the collection?” Certainly this was one of the more unusual (and perhaps inappropriate-sounding) requests Paul Rogers and the rest of the Yosemite archives team had ever received. To his professional credit, he took it in stride and replied: “Who?”

Curious about Old Horny? Read this and more only-inYosemite stories in the new Yosemite Wildlife book, available at shop.Yosemite.org or wherever books are sold.

ABOVE: Julia Hejl stops to enjoy the view on a hike to Glen Aulin.

RIGHT: Julia Hejl helps plant native seeds in Yosemite Valley alongside NPS staff and other Conservancy volunteers.

PHOTOS: (ABOVE)

© YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/ MARION INGERSOLL. (OPPOSITE PAGE)

© YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY/ RILEY APPLEWHITE.

JULIA HEJL plays an important role in connecting donors with the park they love as Yosemite Conservancy’s regional philanthropy director for Southern California. Based in Los Angeles, she works closely with supporters to match their passions with impactful projects in Yosemite, helping to ensure the park is protected for years to come.

Originally from Michigan and raised near Philadelphia, Julia joined the Conservancy in April 2020, bringing her enthusiasm for the outdoors and deep appreciation for the park’s legacy to her role. When she’s not meeting with donors or planning events, she’s likely spending time with her family or out hiking local trails.

If I had to explain my job to a stranger …

I help make the connections between Yosemite Conservancy donors in Southern California and the in-park programs and projects they feel inspired to support. It’s a little like matchmaking — I meet with folks to learn about their interests and identify areas where they can make a meaningful impact in Yosemite National Park.

Colleagues come to me for …

Strong opinions on what paper stock to use for our materials. Beer and food recommendations. Stories about wildlife encounters on my local Monrovia trails (bears and bobcats and deer, oh my!). Early morning coffee deliveries at our donor events.

My favorite part about my job is …

Meeting so many people — donors, colleagues, park partners — who are connected through their love for this incredible place and hearing their stories. Everyone has their own reason why Yosemite is meaningful to them, but it all comes back to making a difference in this place and preserving the park for future generations.

People are surprised to learn this about me …

I didn’t grow up hiking or backpacking. When my husband and I moved to Los Angeles in 2008, we realized how many outdoor gems there are throughout California and started exploring. Now, I’m excited to pass these experiences on to my children. I took my 7-year-old on his first backpacking trip to Mt. San Jacinto this year, and I’m eager for my 4-year-old to join us soon.

I spend my days …

Hiking, trail running, enjoying our native backyard garden, at the library or playground with my kiddos, planning my next adventure in the Sierra … anywhere outdoors!

“The Conservancy is the oldest park partner organization in the country.”

I’m inspired by …

The impact Yosemite Conservancy and our donors have made in the park over 100+ years of partnership. The Conservancy is the oldest park partner organization in the country. Last year, we hosted a conference of similar friends groups from across the country. It was an incredible experience to show off the projects the Conservancy has played a hand in — from the Mariposa Grove to Yosemite Falls to the new Welcome Center. Our work has touched every corner of this park, and I am so proud to be a part of it.

Meep! Meep! American pikas (Ochotona princeps) live year-round in Yosemite’s beautiful, rocky, alpine slopes. During the brief three- to four-month High Sierra summer, Yosemite is SO BIG for pikas! They scamper around collecting plants, drying them on rocks, eventually storing them for winter. Then the snows come and the pikas hunker down in cozy dens, and their Yosemite becomes SO SMALL!

Summer! Yosemite SO BIG! What big adventures have you experienced this summer? Draw or write about your BIG adventure below.

Pikas are masters of mountain living. They thrive during cool summers and snowy winters. As our climate changes, summers are warming and winters are shifting — making life trickier for the pikas. They can’t regulate their body temperatures like we can — too hot for too long can end badly.

The good news? Pikas are finding locations that stay cooler and provide shelter, even when the nearby area heats up.

Stay curious, Junior Rangers!

Winter! Yosemite SO SMALL! Now that winter is coming, how will you make your home as cozy as a pika den? Draw or write your answer below.

Park fans share their photos of Yosemite Autumn Glow Beneath Half Dome © MARC BOULDOUKIAN. Feeling Fungi!

Thanks for sharing your shots, Yosemite fans! To see more photos of the park and stay in the loop with park news, follow @yosemiteconservancy on social media and sign up for our newsletters. Scan the QR code for links.

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

COUNCIL MEMBERS

CHAIR

Steve Ciesinski*

VICE CHAIR

Ryan Myers*

SECRETARY

Robyn Miller*

TREASURER

Jewell Engstrom*

PRESIDENT & CEO

Cassius M. Cash*

COUNCIL

Hollis & Matt* Adams

Matthew Adams

Sarah Adams

Susanah Aguilera & Bob Kiesling

Blerina Aliaj & Alain Rodriguez*

Gretchen Augustyn

David & Amelia Cameron

Jessica* & Darwin Chen

Diane & Steve* Ciesinski

Kira & Craig Cooper

Hal Cranston & Vicki Baker*

John & Meredith Cranston

Carol DeVol & Katy Fox

Carol* & Manny Diaz

Leslie & John Dorman

Dana & Dave Dornsife

Jewell* & Bob Engstrom

Kathy Fairbanks

Bill & Cynthia Floyd

Bonnie Gregory

Rusty Gregory

Laura Hattendorf & Andy Kau

Christina Hurn

Mitsu Iwasaki

Erin & Jeffrey* Lager

Patsy & Tim Marshall

Kirsten & Dan Miks

Robyn* & Joe Miller

Kate & Ryan* Myers

Daniel Paramés

Sharon & Phil Pillsbury

Gisele & Lawson* Rankin

Skip Rhodes

Dave Rossetti* & Jan Avent

Greg & Lisa Stanger

Pranav Sudesh

Ann* & George Sundby

Clifford J. Walker

Wally Wallner & Jill Appenzeller

Ryan & Susan Wiley

Helen & Scott* Witter

*Indicates Board of Trustees

There are many ways you and your organization can support the meaningful work of Yosemite Conservancy. We look forward to exploring these philanthropic opportunities with you.

CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER

Marion Ingersoll mingersoll@yosemite.org 415-362-1464

LEADERSHIP GIFTS – NORTHERN CALIFORNIA & NATIONAL Caitlin Allard callard@yosemite.org 415-989-2848

LEADERSHIP GIFTS –SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

Julia Hejl jhejl@yosemite.org 323-217-4780

PLANNED GIVING & BEQUESTS Catelyn Spencer cspencer@yosemite.org 415-891-1039

VISIT

yosemite.org

EMAIL info@yosemite.org

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

ANNUAL, HONOR, & MEMORIAL GIVING Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemite.org 415-891-2216

MONTHLY GIVING Cailan Ackerman sequoia@yosemite.org 415-966-5252

GIFTS OF STOCK Eryn Roberts stock@yosemite.org 415-891-1383

FOUNDATIONS & CORPORATIONS Laurie Peterson lpeterson@yosemite.org 415-906-1016

Yosemite Conservancy 101 Montgomery Street, Suite 2450 San Francisco, CA 94104

Magazine of Yosemite Conservancy, published twice a year.

MANAGING EDITOR

Zoe Duerksen-Salm

PRODUCTION MANAGER

Josh Byrd

DESIGN

Eric Ball Design

JUNIOR RANGER ILLUSTRATOR

Lou Zabala

Autumn Winter 2025

Volume 16 Issue 02 ©2025

Federal Tax Identification No. 94-3058041

LEADERSHIP

PHONE

415-434-1782

Cassius M. Cash, President & CEO

Kevin Gay, Chief Financial Officer

Marion Ingersoll, Chief Development Officer

Kimiko Martinez, Chief Marketing & Communications Officer

Adonia Ripple, Chief of Yosemite Operations

Schuyler Greenleaf, Chief of Projects

For a full list of staff, visit yosemite.org/staff.

For a full list of our 2025 grants, visit yosemite.org/impact.

WHEN YOU INCLUDE Yosemite Conservancy in your will or trust, or as a beneficiary of your retirement account, you create a legacy that will protect this amazing place for generations to come.

Your gift becomes part of the legacy fund, which makes meaningful work possible and sustains programs that will benefit visitors well into the future. It is a wonderful way to commemorate your special memories in Yosemite National Park, while also ensuring future generations will be able to create memories of their own.

To learn more about a legacy for Yosemite, please contact Catelyn Spencer at cspencer@yosemite.org or 415-891-1039.

yosemite.org/legacy