7 minute read

Unit D. URBAN WATERS, BODIES, (dis-)CONNECTIONS

OUR CHALLENGE: FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE

Water was always an integral resource to urban settlements and a primary link between city knowledge and society building. Across contexts, different typologies of water infrastructures were created by communities as ways to use, channel and control this precious natural resource. Around this, cultural and social practices have emerged, underpinning how people connect to the built environment and its resources. At the same time, throughout history, we have witnessed an accelerated loss of the connection between the city and water. Certain urban waterscapes have become forgotten, by-passed, abused or left to decay and pollution. Yet, they remain an integral asset of cultural heritage and a precious ecological resource today. Linking the past to the present and future, heritage is understood through its tangible assets, such as buildings, sites and environments, in addition to intangible assets such as “practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills” that are fundamental to the life of people and cities (UNESCO 2021).

Advertisement

OUR PROCESS: LEARNING BY RESEARCH, DESIGN AND IMAGINATION

We strongly believe in the transformative potential of both water and heritage “to connect sites of living heritage with each other; water-related heritage’s capacity to connect past, present, and future; and water’s role as heritage in spatial developments, landscape design, and urban planning remain underestimated and underexplored.” (Hein 2020).

We propose creative investigations of the multidimensional forms of connections and disruptions in different contexts. We look for what has been lost or forgotten. We also look at how urban actors creatively build, repair and maintain the relations between water, people and urban space (Willems and Van Schaik 2015). We explore the opportunity to reimagine these links at different scales and from different perspectives. a. The conceptual: This is our space to identify the problems and shape our research by design questions, a space of investigation and abstraction where designers learn how to deal with complex situations through drawings and diagrams. b. The descriptive: This is our space to identify the agency of the design project and our role as designers: when, if at all, do we intervene and how? What is working, and what needs repairing? c. The imaginative: This is our space to imagine future spatial conditions, an iterative process of doing, undoing and redoing. Scenarios are a form of scientific investigation into a possible future.

We will then consider how, why, and when the city’s development has impacted them on the spatial, social and cultural levels.

We will finally test the agency of design to question, repair and upscale these links and imagine the scenarios where people, water bodies, and the city evolve in synergy. We will be testing the following three-fold framework to unpack how the design project can lead our research by design method and produce knowledge (Viganò 2016).

OUR

TOOLS: CRITICAL AND CREATIVE MULTIMEDIA

We employ various creative and analytical tools to understand and analyse urban environments parallel to developing architectural reflections and proposals. These include but are not limited to:

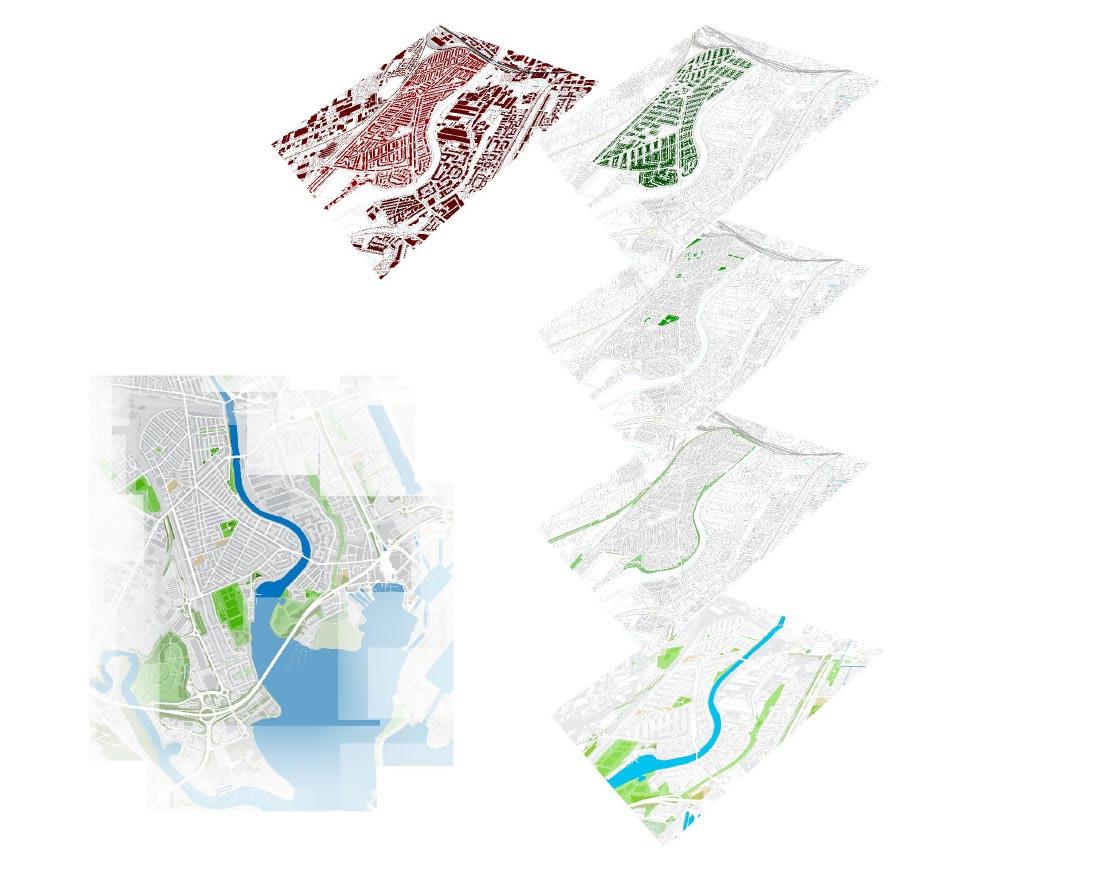

Urban mapping, 2D and 3D representations in multimedia forms, including hand-sketching, digital drawings, model making, diagrams and illustrations group discussion of critical readings and creative writing, site visits, photography and urban sketching comparative analysis and analysis of precedents.

OUR PROGRESS: ITERATIVE AND COMPARATIVE

Phase I. We will investigate the Royal Docks, London, to produce a broad knowledge of the site, identify the challenges surrounding urban waters at the intersection with cultural heritage and formulate coherent and compelling research by design questions. In parallel, we will create a series of scenarios that illustrate, describe and tackle the current social and ecological challenges. The scenarios will form the backdrop to future architectural experimentations.

Phase II. This phase is divided into two stages.

Stage 1- We will develop the research questions and scenarios to reflect upon them in different contexts worldwide by undertaking a comparative analysis of relevant case studies. These comparative case studies will be as follows:

Beirut waterfront, Lebannon: fighting for the right to the sea

Napoli Est, Italy: the connection between deindustrialisation, rising water table and pollution in a large brownfield site in Naples, Italy.

Cardiff Glamorganshire canal, Wales, UK: effects of the tides and traces of industrial past.

Stage 2 - Within these urban scenarios, we will explore the guiding role of architectural design. We will focus on a cluster of sites in the Royal Docks of London. Individual design projects must demonstrate coherence with the research by design questions and scenarios elaborated in Phases I and II. The term ends with the presentation of designresearch investigations and spatial interventions through a coherent portfolio and a reflective diary.

Reading list

On water, city and design

• AA.VV., “Green Metaphor”, Lotus n. 135/2008. “Landscape Infrastructures”, Lotus n. 139/2009

• Allen, S. 1999, Infrastructural urbanism, in: Allen, S., Points + Lines: Diagrams and projects for the city, New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

• Barsley, E., 2020, Retrofitting for Urban Resilience, RIBA Publishing

• Bélanger, P. 2009, “Landscape as Infrastructure”, Landscape Journal 28.

• Bell, S. Ed., 2022, Urban Blue Spaces, Routledge

• Clément, G. 2004, Manifeste fu Tiers Paysage, Paris: sujet/objet

• Dreisetl, H, 2009, Recent Waterscapes, Birkhauser

• Gandy M. 2003, Concrete and clay, reworking nature in the contemporary city, Boston: MIT Press.

• McHarg, I. 2006, The essential Ian McHarg. Writings on design and nature, Washington, DC: Island Press.

• Mostafavi, M., Doherty G., (editor) 2010, Ecological Urbanism, Baden: Lars Muller Publishers

• Palazzo,D., Steiner, F., 2012, Urban Ecological Design, Springer

• Shannon, K. 2011, “Return to Landscape Urbanism”, in: Ferrario, V., Sampieri,

• Turner, T. 1996, City as Landscape, Taylor Francis

• Viganò, P. 2016, Territories of Urbanism: The Project as Knowledge Producer, Lausanne: EPFL Press.

• Secchi, B. 2013, The city of the rich and the city of the poor, Laterza

• Wittfogel, K. 1956, ‘The Hydraulic Civilizations,’ in W.L. Thomas (ed.) Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

On critical heritage

• Ahmad, Y., 2006. The scope and definitions of heritage: from tangible to intangible. International journal of heritage studies, 12(3), pp.292-300.

• Harrison, R., 2012. Heritage: critical approaches. Routledge.

• Hein, C., 2020. Adaptive strategies for water heritage: Past, present and future (p. 435). Springer Nature.

• Lynch K. 1972, What time is this place, Boston: the MIT Press.

• Smith, L., 2006. Uses of heritage. Routledge.

• Willems, W.J. and Van Schaik, H., 2015. Water and Heritage: Material, conceptual and spiritual connections (p. 434). Sidestone Press.

On the Royal Docks

• Royal Docks’ website by Mayor of London and Newham Council: https:// www.royaldocks.london/opportunity

• Previous research and projects done at UCL: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ bartlett/development/programmes/msc-building-and-urban-design-

2.2 MA AD reading List

Design Research References

• Blythe, R., Stamm, M. 2017. Doctoral Training for Practitioners: ADAPT-r (Architecture, Design and Art Practice Research) A European Commission Marie Curie Initial Training Network’, In Vaughan L. (ed.) Practice Based Design Research, London: Bloomsbury, 53-63.

• Coyne, R. 2006. Creative practice and design-led research, Class Notes 28 November 2006.

• Ehn, P. and Ullmark, P. 2017. Educating the Reflective Design Researcher. Practice-based Design Research.London: Bloomsbury, 77-86.

• Fraser, M. 2013. Design Research in Architecture: an overview. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd

• RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects), Research in Practice Guide Research Through Design (RTD) Conference series

• Schaik, L. V. 2009. Design Practice Research, the Method. In Verbeke, J. (ed.) Reflections, Brussels: Sint Lucas. University of Leuven.

• Till, J. 2007. Three Myths and One Model in Collected Writing

Ways of seeing, thinking and doing architecture

• Chard, N. and Kulper, P., eds. 2013. Contingent Practices. London: Ashgate.

• Deplazes, A. 2013. Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures. Basel: Birkhauser Verlag, 3rd Edition.

• Dovey, K. 2010. Becoming Places: Urbanism / Architecture / Identity / Power.

• Fainstein, S. 2011. The just city. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 27(1), pp. 107-109.

• Frampton, K. 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, MIT Press.

• Hawkes, D. 1996. The environmental tradition: studies in the architecture of environment. London: Spon.

• Hernandez, F. 2010. Bhabha for Architects: Thinkers for Architects, London: Routledge.

• Hertzberger, H. 2016, Lessons for students in architecture, Rotterdam : nai010 publishers.

• Jacobs, J. 1992. The death and life of great American cities. 1961. New York: Vintage.

• Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City, London: M.I.T. Press.

• Rem, K. 1994. Delirious New York : a retroactive manifesto for Manhattan. 2, p. 498.

• Reed, C., Lister, N., eds. 2015. Projective Ecologies. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Graduate School of Design and ACTAR

• Rykwert, J., 2000. Seduction of place: The city in the twenty-first century. Pantheon.

• Richard, S. 2009. The Craftsman. London and New York: Penguin.

• Sharr, A. ed. 2012. Reading architecture and culture: researching buildings, spaces, and documents. Routledge.

• Jeremy, T. Awan, N and Schneider, T. 2011. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. London: Routledge.

• Tonkiss, F. 2014. Cities by Design. Oxford: Polity Press Malden, MA: Polity.

• Unwin, S. 2014. Analysing architecture. Fourth edition,. London ; New York : Routledge.

• Unwin, S. 2015. Twenty Five Buildings every Architect Should Understand, London ; New York : Routledge

• Vidler, A. 1992. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, Mass, The MIT press.

Student Name:Siyan Tao

Unit A: EMUVE Unit Lewisham 2021: Inter-Cultural Nodes

Project: Tidemill Community: A Co-managed Learning Space

In today’s highly intercultural society, the study of how to promote interaction between people from different backgrounds is a topic of great significance. Redesigning in community spaces (in-between space) to create engaging (montage) intercultural (multilingual) learning spaces (programmes) that help to activate historic buildings, showcase the rich history of the Deptford and reclaim the memory of the site. By turning the ‘optional’ diversity into a ‘necessary’ feature of the intervention site. The designed community public space becomes a bridge of inclusion, allowing intercultural exchange and diversity into the everyday life of people living together.

Student Name: Kai Huang

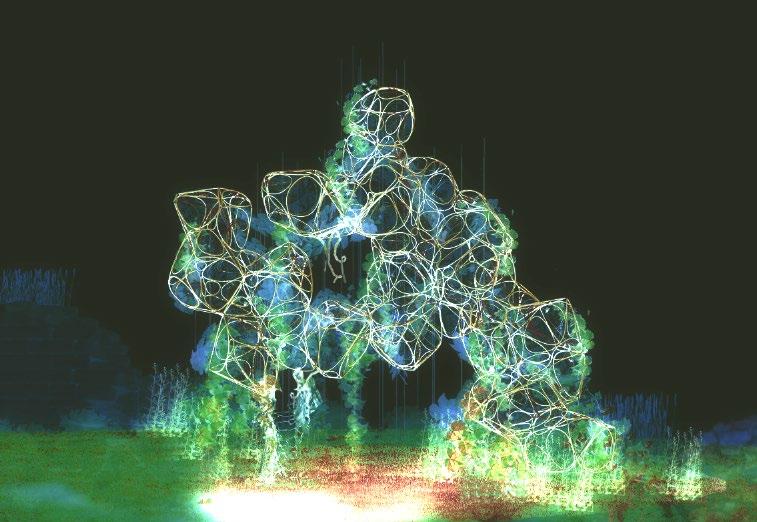

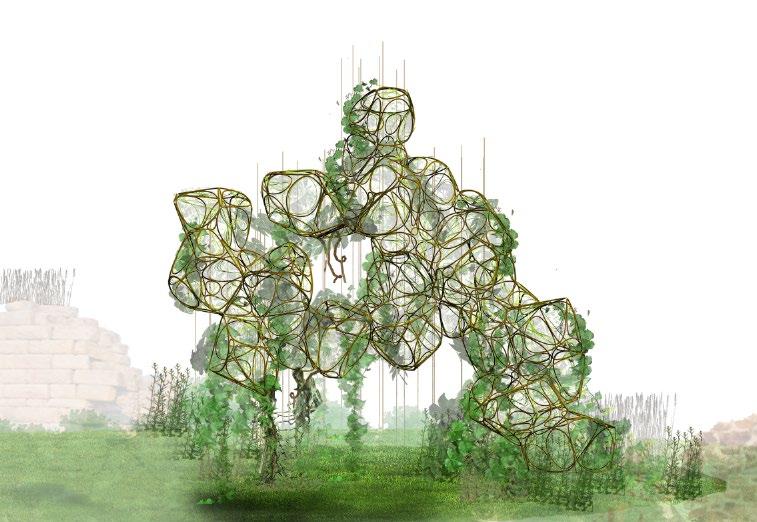

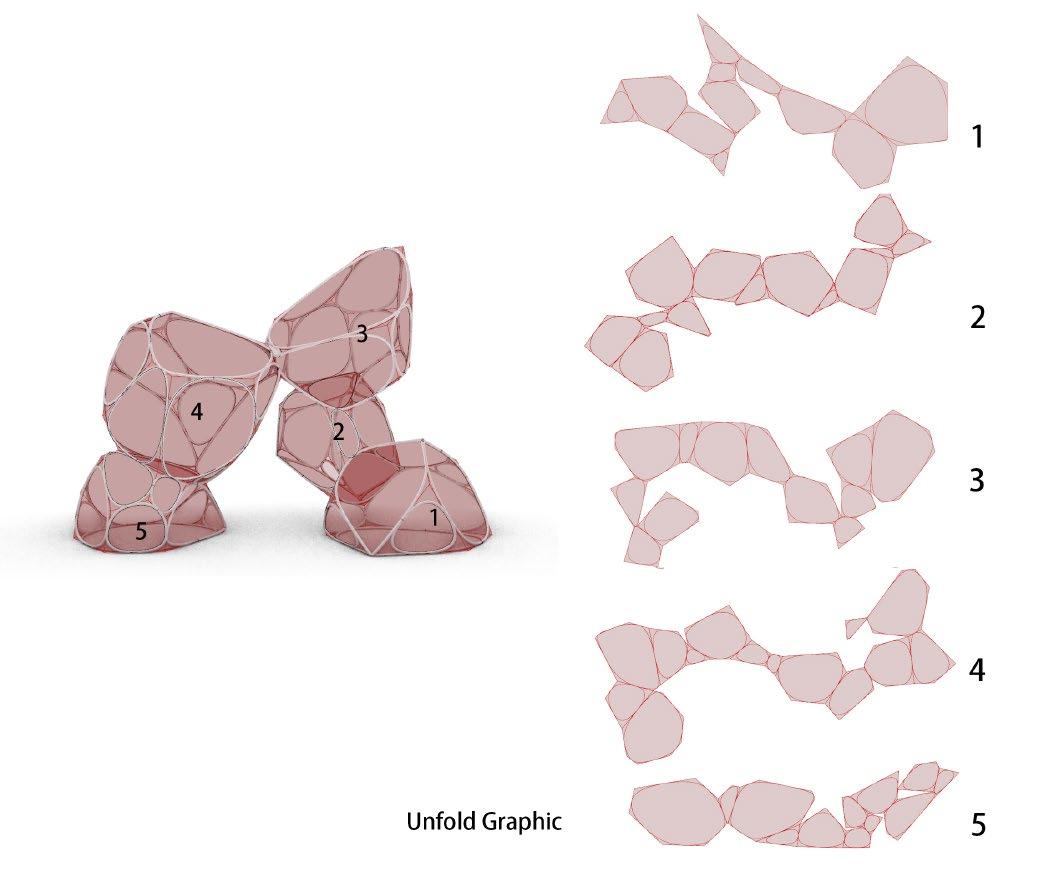

Unit B: Synergetic Landscapes

Project: DIVERSIFIED SYMBIOSIS- The Systemic Design Via Blockchain

This includes four different types of services:

1. Support -- including oxygen production, nutrient cycling and soil formation.

2. Regulation - including climate regulation, flood control and water purification.

3. Supply - Provides us with food, fuel, fibre and water.

4. Cultural Services - We enjoy wildlife and countryside, education, recreation, inspiration and natural beauty.

Student Name: Yijia Chen

Unit C: Questioning the Ambivalence of Urban Commons

Project: Design for street 93, Phnom Phem

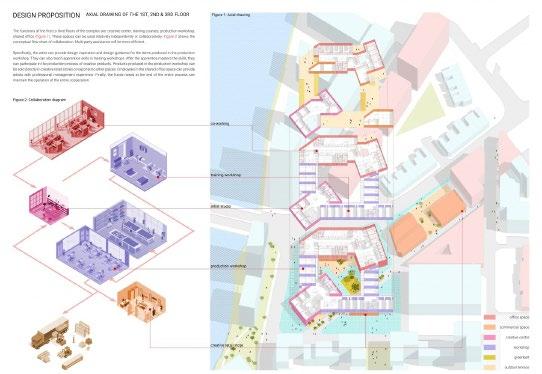

Design Proposal for Street 93, Phnom Phem

Urban Acupuncture, a way of planning that pinpoints vulnerable sectors of a city and re-energizes them through design intervention (Quirk 2012). So the design intervention is to select the most critical location, intervene slightly, and give the appropriate functions to carry out public activities to activate the entire block.