19 minute read

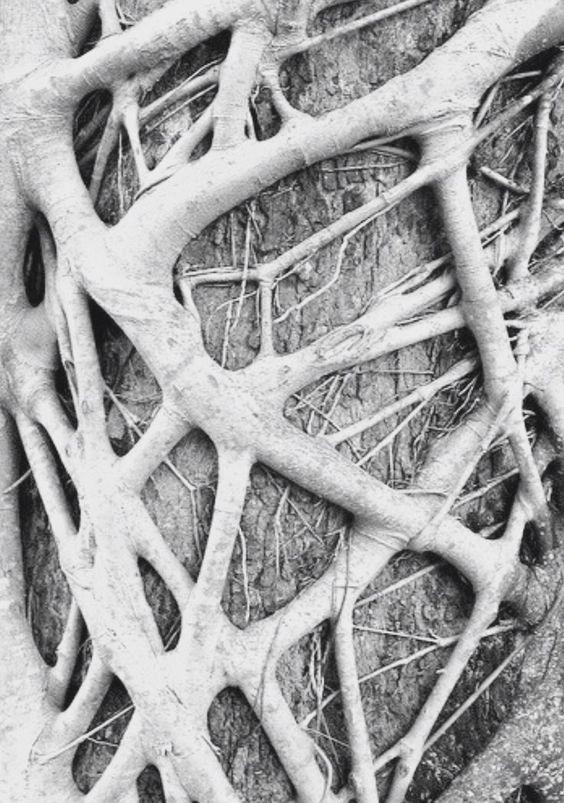

Unit D. URBAN WATERS, BODIES, (dis-)CONNECTIONS

OUR CHALLENGE: FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE

Water was always an integral resource to urban settlements and a primary link between city knowledge and society building. Across contexts, different typologies of water infrastructures were created by communities as ways to use, channel and control this precious natural resource. Around this, cultural and social practices have emerged, underpinning how people connect to the built environment and its resources. At the same time, throughout history, we have witnessed an accelerated loss of the connection between the city and water. Certain urban waterscapes have become forgotten, by-passed, abused or left to decay and pollution. Yet, they remain an integral asset of cultural heritage and a precious ecological resource today. Linking the past to the present and future, heritage is understood through its tangible assets, such as buildings, sites and environments, in addition to intangible assets such as “practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills” that are fundamental to the life of people and cities (UNESCO 2021).

Advertisement

OUR PROCESS: LEARNING BY RESEARCH, DESIGN AND IMAGINATION

We strongly believe in the transformative potential of both water and heritage “to connect sites of living heritage with each other; water-related heritage’s capacity to connect past, present, and future; and water’s role as heritage in spatial developments, landscape design, and urban planning remain underestimated and underexplored.” (Hein 2020). We propose creative investigations of the multidimensional forms of connections and disruptions in different contexts. We look for what has been lost or forgotten. We also look at how urban actors creatively build, repair and maintain the relations between water, people and urban space (Willems and Van Schaik 2015). We explore the opportunity to reimagine these links at different scales and from different perspectives. We will then consider how, why, and when the city’s development has impacted them on the spatial, social and cultural levels. a. The conceptual: This is our space to identify the problems and shape our research by design questions, a space of investigation and abstraction where designers learn how to deal with complex situations through drawings and diagrams. b. The descriptive: This is our space to identify the agency of the design project and our role as designers: when, if at all, do we intervene and how? What is working, and what needs repairing? c. The imaginative: This is our space to imagine future spatial conditions, an iterative process of doing, undoing and redoing. Scenarios are a form of scientific investigation into a possible future.

We will finally test the agency of design to question, repair and upscale these links and imagine the scenarios where people, water bodies, and the city evolve in synergy. We will be testing the following three-fold framework to unpack how the design project can lead our research by design method and produce knowledge (Viganò 2016).

OUR TOOLS: CRITICAL AND CREATIVE MULTIMEDIA

We employ various creative and analytical tools to understand and analyse urban environments parallel to developing architectural reflections and proposals. These include but are not limited to:

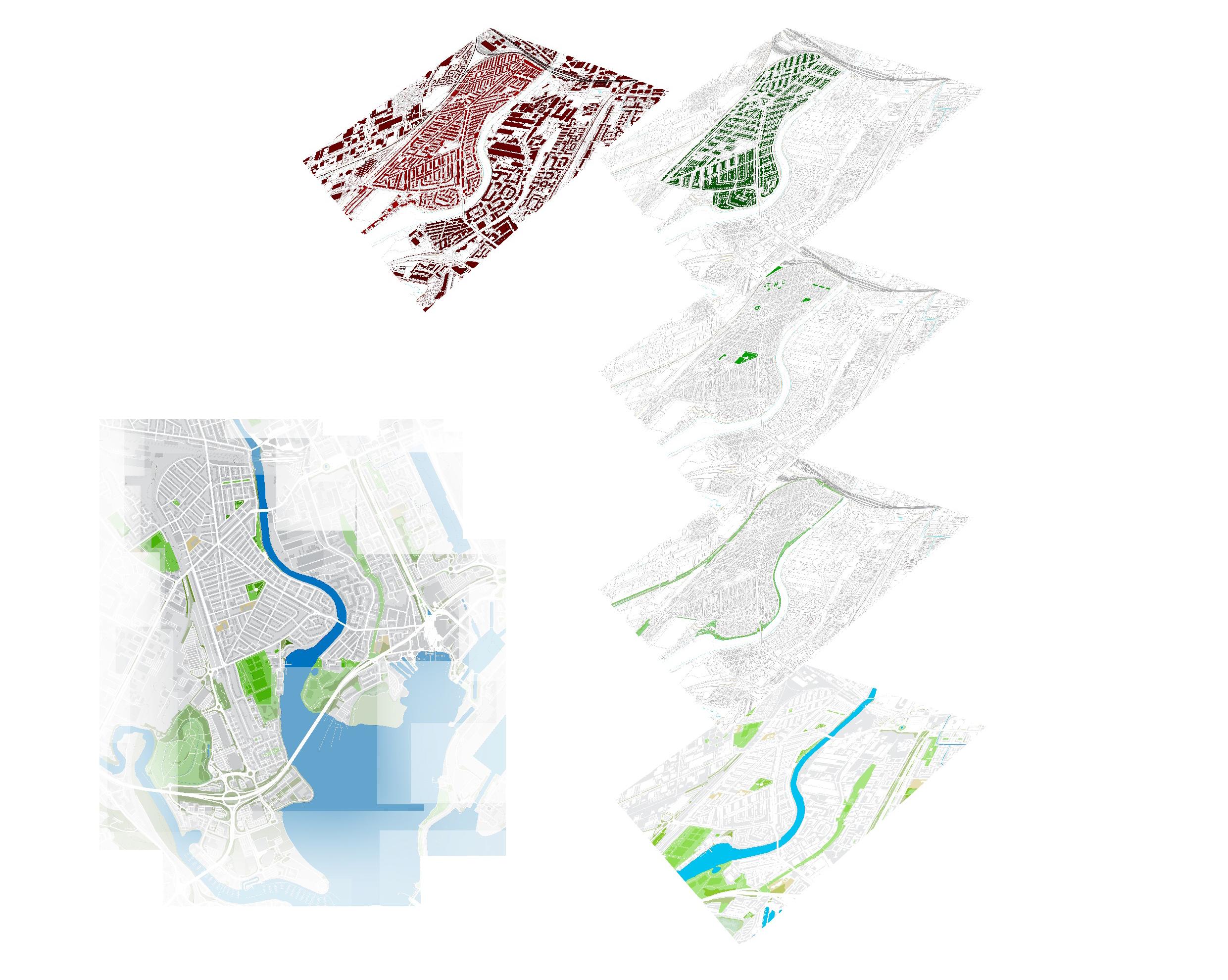

Urban mapping, 2D and 3D representations in multimedia forms, including hand-sketching, digital drawings, model making, diagrams and illustrations group discussion of critical readings and creative writing, site visits, photography and urban sketching comparative analysis and analysis of precedents.

OUR PROGRESS: ITERATIVE AND COMPARATIVE

Phase I. We will investigate the Royal Docks, London, to produce a broad knowledge of the site, identify the challenges surrounding urban waters at the intersection with cultural heritage and formulate coherent and compelling research by design questions. In parallel, we will create a series of scenarios that illustrate, describe and tackle the current social and ecological challenges. The scenarios will form the backdrop to future architectural experimentations.

Phase II. This phase is divided into two stages.

Stage 1- We will develop the research questions and scenarios to reflect upon them in different contexts worldwide by undertaking a comparative analysis of relevant case studies. These comparative case studies will be as follows:

Beirut waterfront, Lebannon: fighting for the right to the sea

Napoli Est, Italy: the connection between deindustrialisation, rising water table and pollution in a large brownfield site in Naples, Italy.

Cardiff Glamorganshire canal, Wales, UK: effects of the tides and traces of industrial past.

Stage 2 - Within these urban scenarios, we will explore the guiding role of architectural design. We will focus on a cluster of sites in the Royal Docks of London. Individual design projects must demonstrate coherence with the research by design questions and scenarios elaborated in Phases I and II. The term ends with the presentation of designresearch investigations and spatial interventions through a coherent portfolio and a reflective diary.

Reading list

On water, city and design

• AA.VV., “Green Metaphor”, Lotus n. 135/2008. “Landscape Infrastructures”, Lotus n. 139/2009

• Allen, S. 1999, Infrastructural urbanism, in: Allen, S., Points + Lines: Diagrams and projects for the city, New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

• Barsley, E., 2020, Retrofitting for Urban Resilience, RIBA Publishing

• Bélanger, P. 2009, “Landscape as Infrastructure”, Landscape Journal 28.

• Bell, S. Ed., 2022, Urban Blue Spaces, Routledge

• Clément, G. 2004, Manifeste fu Tiers Paysage, Paris: sujet/objet

• Dreisetl, H, 2009, Recent Waterscapes, Birkhauser

• Gandy M. 2003, Concrete and clay, reworking nature in the contemporary city, Boston: MIT Press.

• McHarg, I. 2006, The essential Ian McHarg. Writings on design and nature, Washington, DC: Island Press.

• Mostafavi, M., Doherty G., (editor) 2010, Ecological Urbanism, Baden: Lars Muller Publishers

• Palazzo,D., Steiner, F., 2012, Urban Ecological Design, Springer

• Shannon, K. 2011, “Return to Landscape Urbanism”, in: Ferrario, V., Sampieri,

• Turner, T. 1996, City as Landscape, Taylor Francis

• Viganò, P. 2016, Territories of Urbanism: The Project as Knowledge Producer, Lausanne: EPFL Press.

• Secchi, B. 2013, The city of the rich and the city of the poor, Laterza

• Wittfogel, K. 1956, ‘The Hydraulic Civilizations,’ in W.L. Thomas (ed.) Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

On critical heritage

• Ahmad, Y., 2006. The scope and definitions of heritage: from tangible to intangible. International journal of heritage studies, 12(3), pp.292-300.

• Harrison, R., 2012. Heritage: critical approaches. Routledge.

• Hein, C., 2020. Adaptive strategies for water heritage: Past, present and future (p. 435). Springer Nature.

• Lynch K. 1972, What time is this place, Boston: the MIT Press.

• Smith, L., 2006. Uses of heritage. Routledge.

• Willems, W.J. and Van Schaik, H., 2015. Water and Heritage: Material, conceptual and spiritual connections (p. 434). Sidestone Press.

On the Royal Docks

• Royal Docks’ website by Mayor of London and Newham Council: https:// www.royaldocks.london/opportunity

• Previous research and projects done at UCL: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ bartlett/development/programmes/msc-building-and-urban-design-

2.2 MA AD reading List

Design Research References

• Blythe, R., Stamm, M. 2017. Doctoral Training for Practitioners: ADAPT-r (Architecture, Design and Art Practice Research) A European Commission Marie Curie Initial Training Network’, In Vaughan L. (ed.) Practice Based Design Research, London: Bloomsbury, 53-63.

• Coyne, R. 2006. Creative practice and design-led research, Class Notes 28 November 2006.

• Ehn, P. and Ullmark, P. 2017. Educating the Reflective Design Researcher. Practice-based Design Research.London: Bloomsbury, 77-86.

• Fraser, M. 2013. Design Research in Architecture: an overview. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd

• RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects), Research in Practice Guide Research Through Design (RTD) Conference series

• Schaik, L. V. 2009. Design Practice Research, the Method. In Verbeke, J. (ed.) Reflections, Brussels: Sint Lucas. University of Leuven.

• Till, J. 2007. Three Myths and One Model in Collected Writing

Ways of seeing, thinking and doing architecture

• Chard, N. and Kulper, P., eds. 2013. Contingent Practices. London: Ashgate.

• Deplazes, A. 2013. Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures. Basel: Birkhauser Verlag, 3rd Edition.

• Dovey, K. 2010. Becoming Places: Urbanism / Architecture Identity / Power.

• Fainstein, S. 2011. The just city. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 27(1), pp. 107-109.

• Frampton, K. 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, MIT Press.

• Hawkes, D. 1996. The environmental tradition: studies in the architecture of environment. London: Spon.

• Hernandez, F. 2010. Bhabha for Architects: Thinkers for Architects, London: Routledge.

• Hertzberger, H. 2016, Lessons for students in architecture, Rotterdam nai010 publishers.

• Jacobs, J. 1992. The death and life of great American cities. 1961. New York: Vintage.

• Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City, London: M.I.T. Press.

• Rem, K. 1994. Delirious New York : a retroactive manifesto for Manhattan. 2, p. 498.

• Reed, C., Lister, N., eds. 2015. Projective Ecologies. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Graduate School of Design and ACTAR

• Rykwert, J., 2000. Seduction of place: The city in the twenty-first century. Pantheon.

• Richard, S. 2009. The Craftsman. London and New York: Penguin.

• Sharr, A. ed. 2012. Reading architecture and culture: researching buildings, spaces, and documents. Routledge.

• Jeremy, T. Awan, N and Schneider, T. 2011. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture London: Routledge.

• Tonkiss, F. 2014. Cities by Design. Oxford: Polity Press Malden, MA: Polity.

• Unwin, S. 2014. Analysing architecture Fourth edition,. London ; New York Routledge.

• Unwin, S. 2015. Twenty Five Buildings every Architect Should Understand, London ; New York Routledge

• Vidler, A. 1992. The Architectural Uncanny Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, Mass, The MIT press.

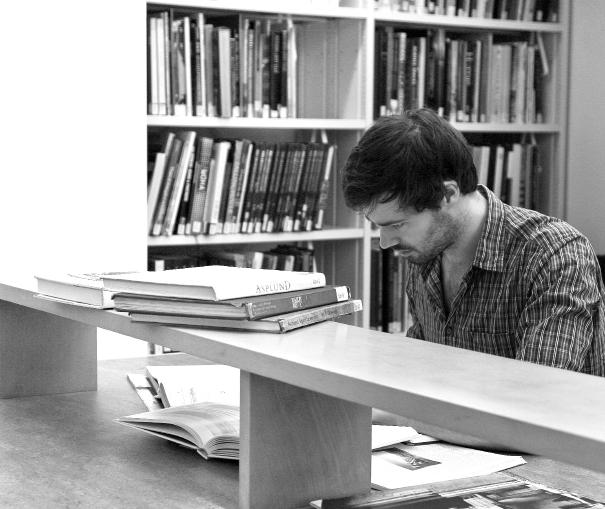

Student Name:Siyan Tao

Unit A: EMUVE Unit Lewisham 2021: Inter-Cultural Nodes

Project: Tidemill Community: A Co-managed Learning Space

Student Name: Kai Huang

Unit B: Synergetic Landscapes

Project: DIVERSIFIED SYMBIOSIS- The Systemic Design Via Blockchain

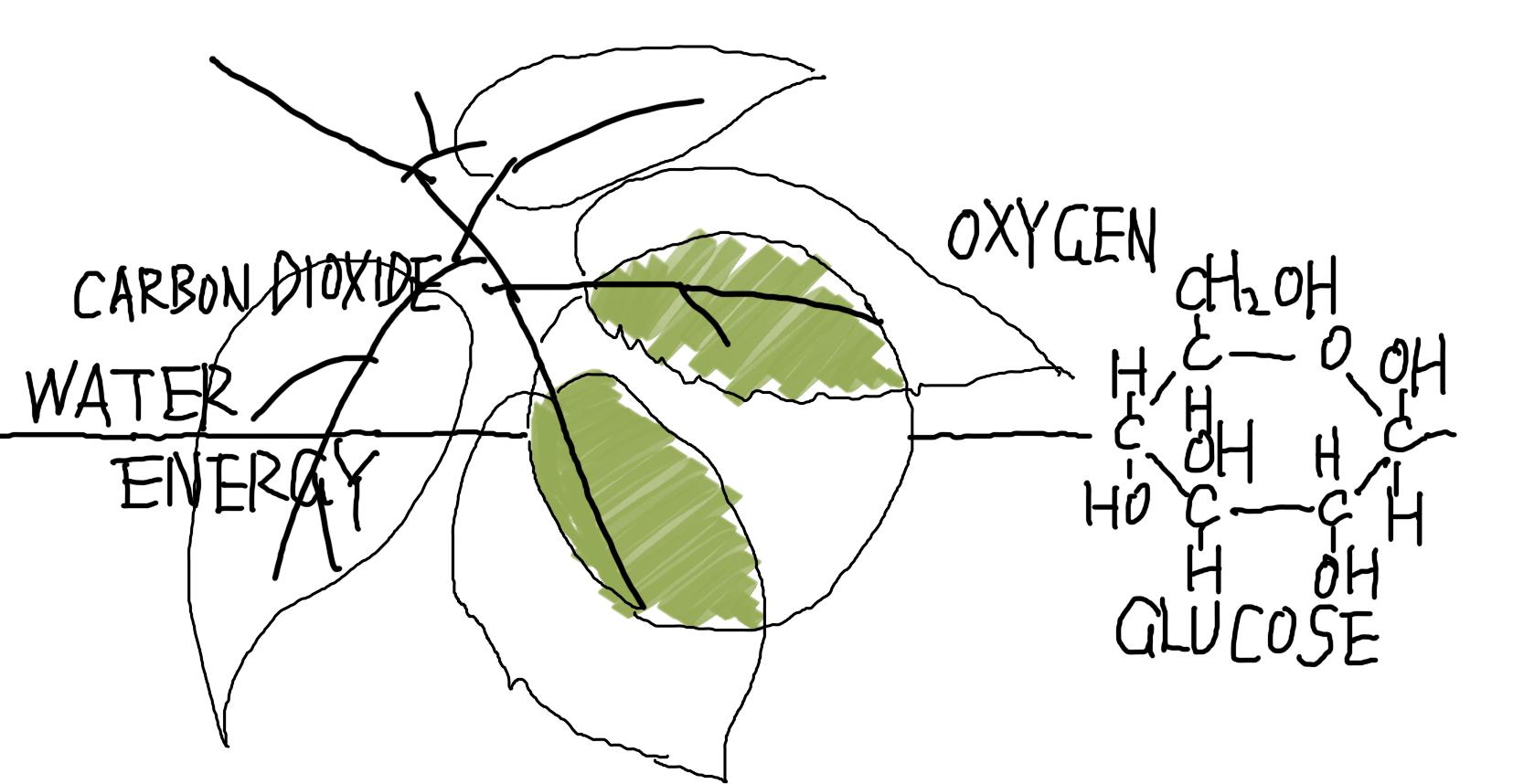

This includes four different types of services:

1. Support -- including oxygen production, nutrient cycling and soil formation.

2. Regulation - including climate regulation, flood control and water purification.

3. Supply - Provides us with food, fuel, fibre and water.

4. Cultural Services - We enjoy wildlife and countryside, education, recreation, inspiration and natural beauty.

In today’s highly intercultural society, the study of how to promote interaction between people from different backgrounds is a topic of great significance. Redesigning in community spaces (in-between space) to create engaging (montage) intercultural (multilingual) learning spaces (programmes) that help to activate historic buildings, showcase the rich history of the Deptford and reclaim the memory of the site. By turning the ‘optional’ diversity into a ‘necessary’ feature of the intervention site. The designed community public space becomes a bridge of inclusion, allowing intercultural exchange and diversity into the everyday life of people living together.

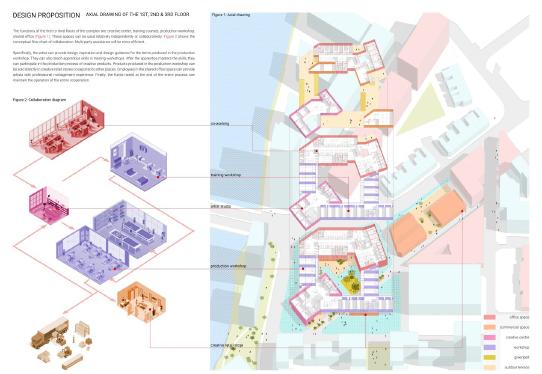

Student Name: Yijia Chen

Unit C: Questioning the Ambivalence of Urban Commons

Project: Design for street 93, Phnom Phem

Design Proposal for Street 93, Phnom Phem

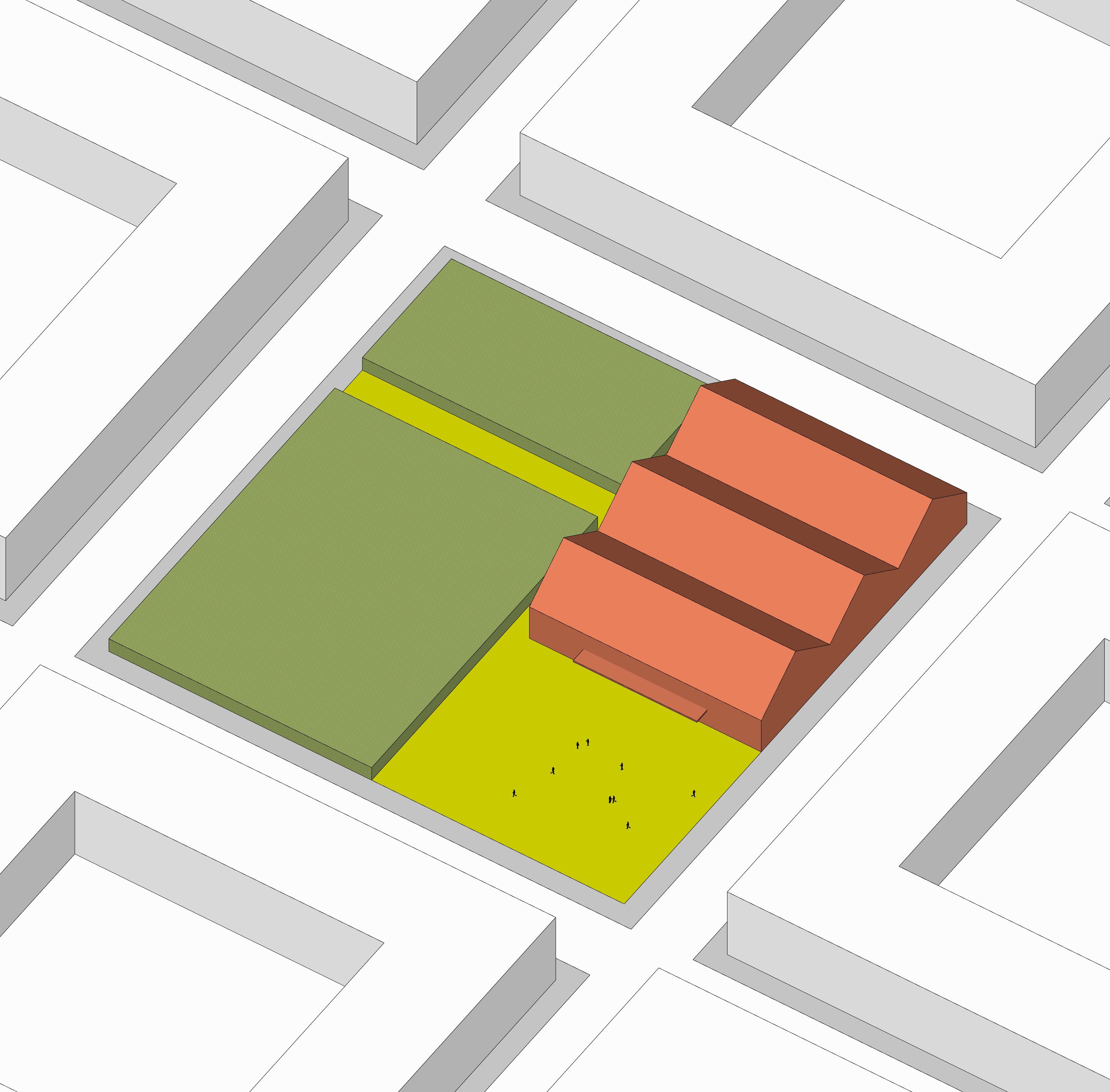

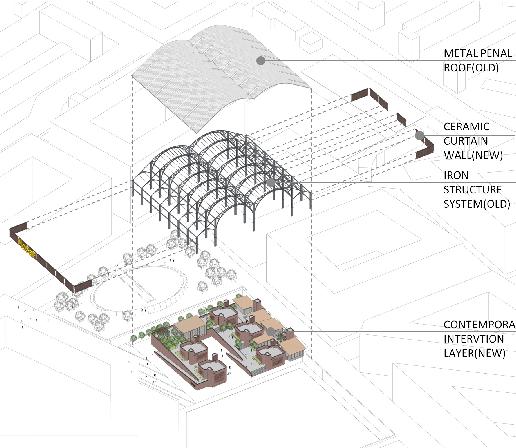

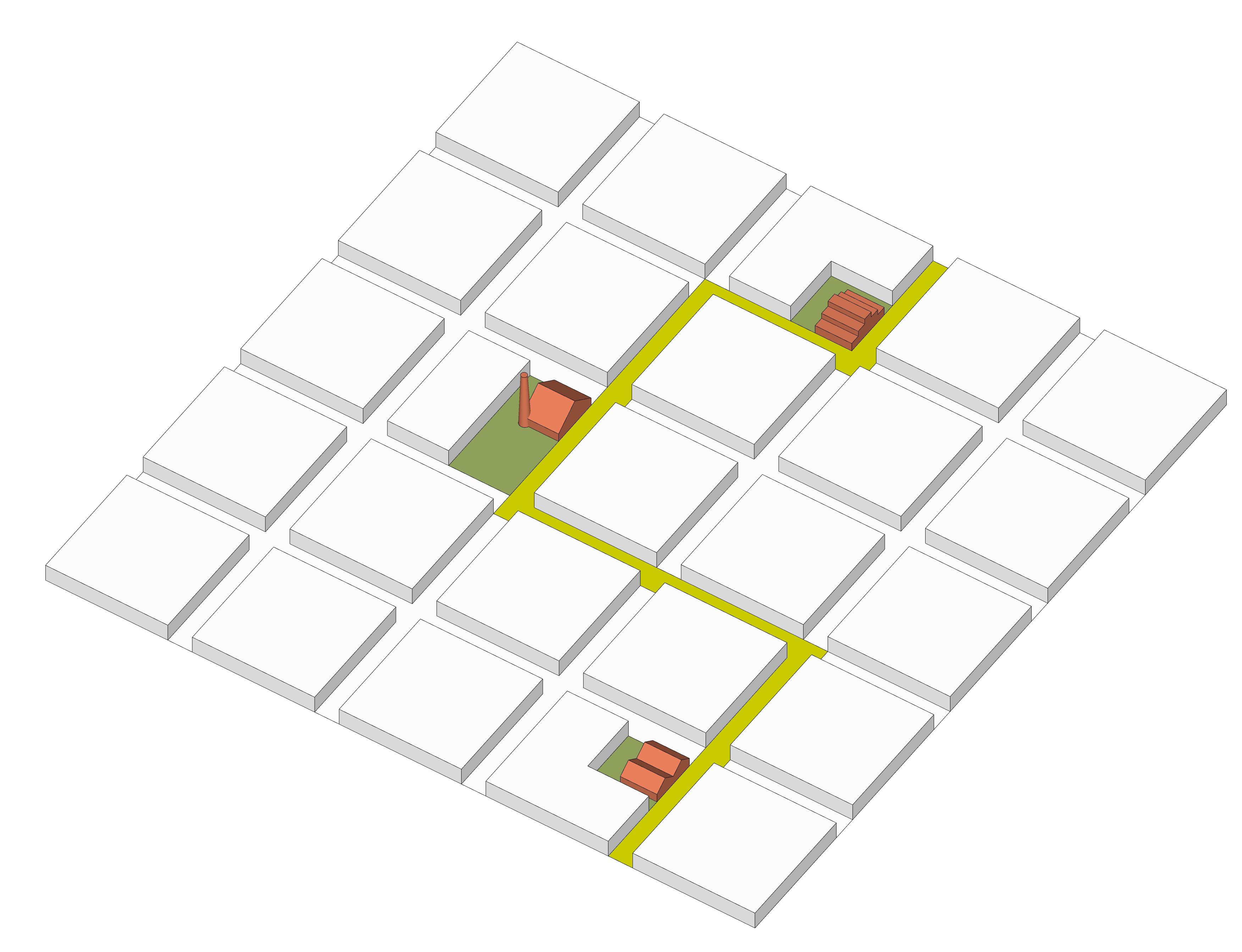

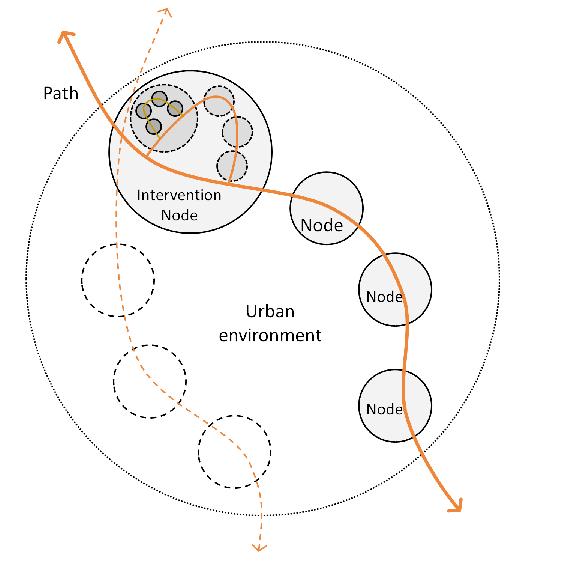

Urban Acupuncture, a way of planning that pinpoints vulnerable sectors of a city and re-energizes them through design intervention (Quirk 2012). So the design intervention is to select the most critical location, intervene slightly, and give the appropriate functions to carry out public activities to activate the entire block.

Student Name: Yanfang Zuo

Unit D: EMUVE Unit Lewisham 2021: Inter-Cultural Nodes

Project: Design of MOSAF Inter-cultural Nodes

Interculturality has become the common goal of diversity in European cities, where different cultural groups lack interaction today. With the degradation of urban environments, the Inter-Cultural Nodes (ICN) act as catalysts by activating heritage building as intercultural space for all groups, shaping appropriate citizenship. Montage theory is chosen as a tool from finding literature reviews and case studies for curating spaces in urban scale, intermediate scale and architectural scale. A montage path curated in Convoys Wharf of Deptford links to formal space. It acts as an in-between and informal space where social events and activities are present for all, e.g., the locals, migrants, refugees and tourists, to engage and encounter. By experiencing the curated space through multiple narratives, visitors can understand the hidden history and form collective memory, which all contribute to fostering democratic citizenship, thus shaping a more socially just and equal futures.

Section 3: MA AD support

3.1 Other Optional Components

The students will choose 30 credits worth of optional modules, chosen from the list of subjects based on the research interests of the staff in the school described above in p.5 of this Handbook. The students can select any combination of 10 and 20 credit modules for their option. Optional modules available for 2022-2023 are the following:

AR3003 Issues in Contemporary Architecture (10Cr.)

This course is an introduction to critical thinking in architectural theory. The scope covers ‘contemporary’ issues that are currently under debate in architectural theory, research, and practice.

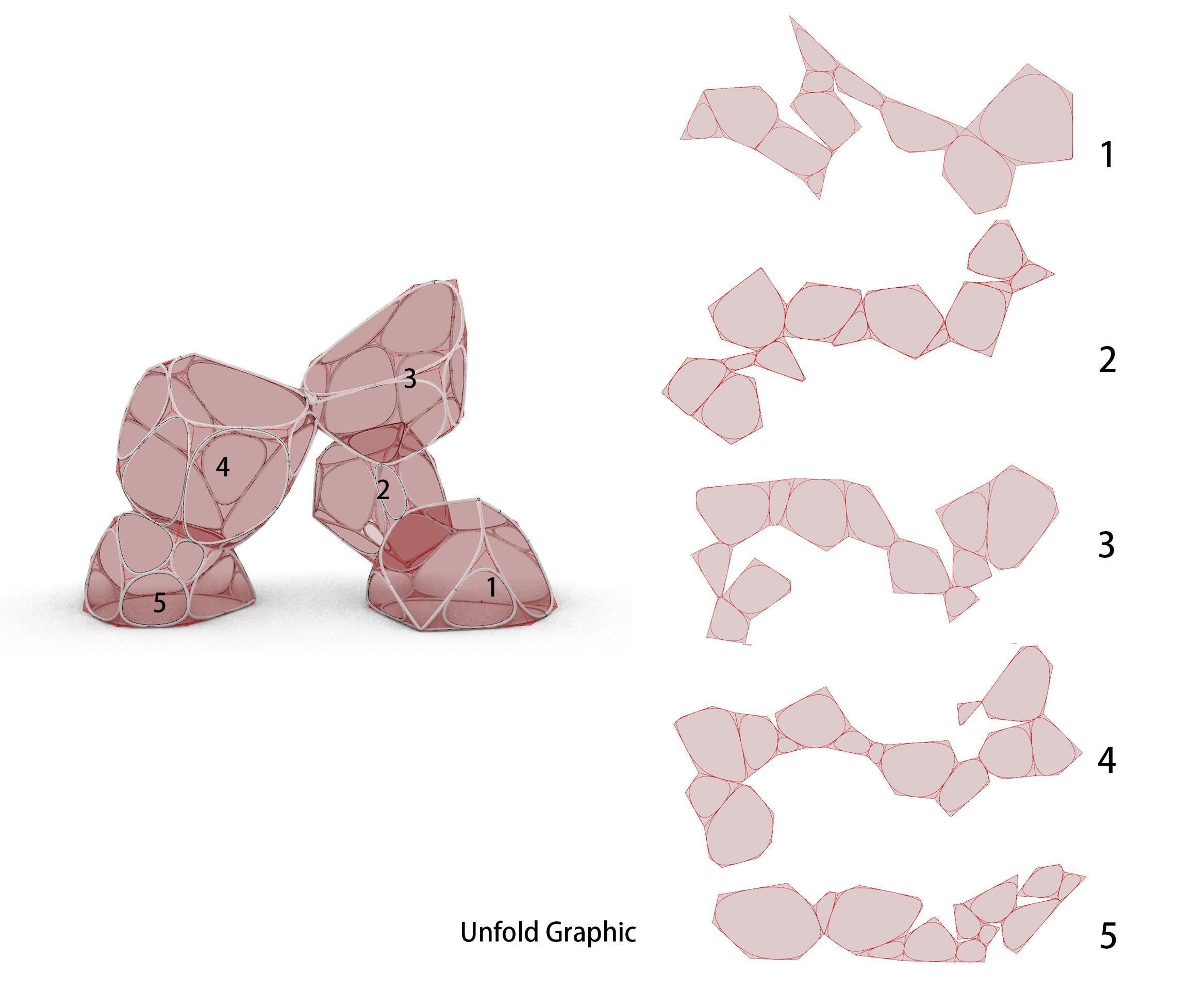

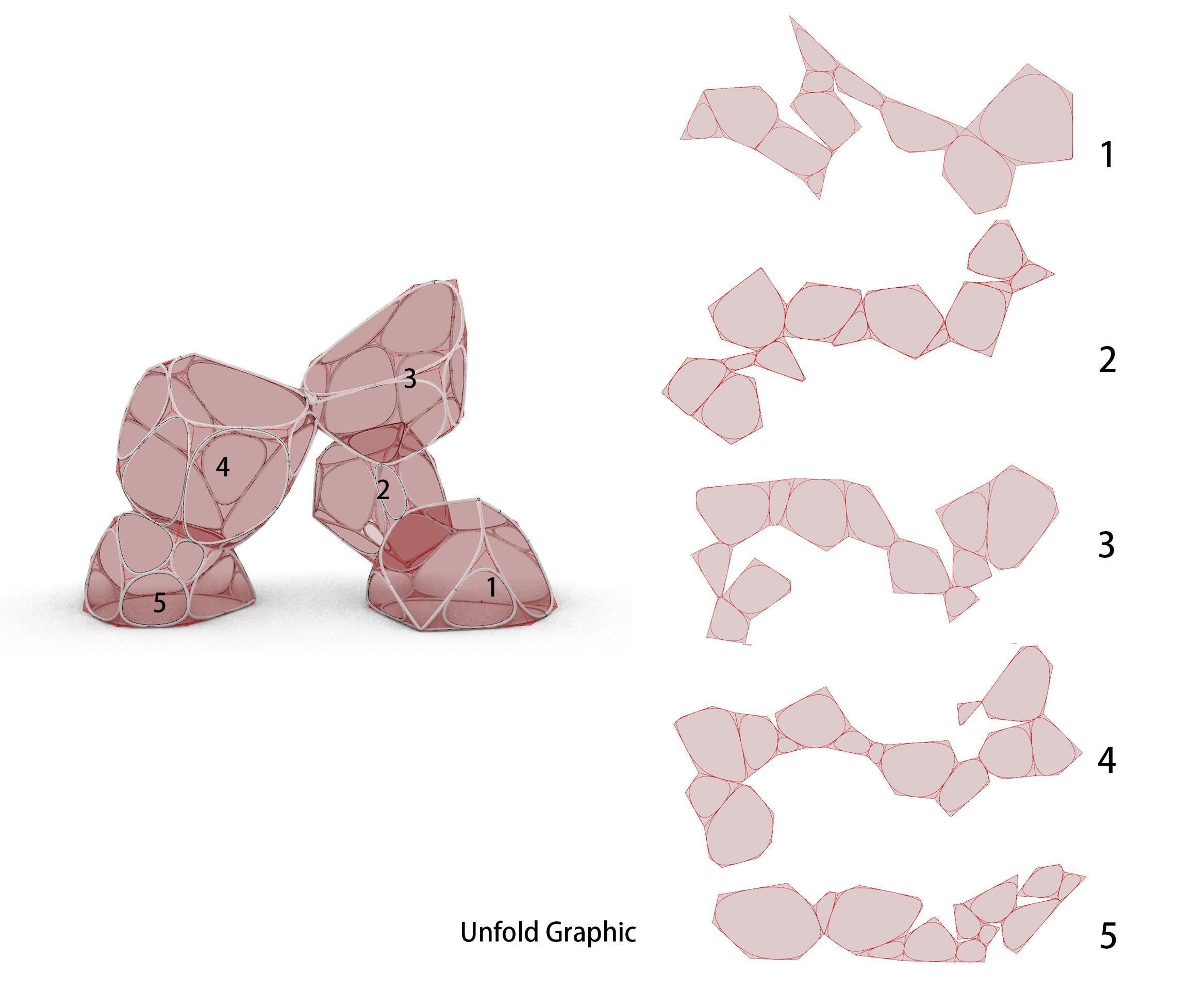

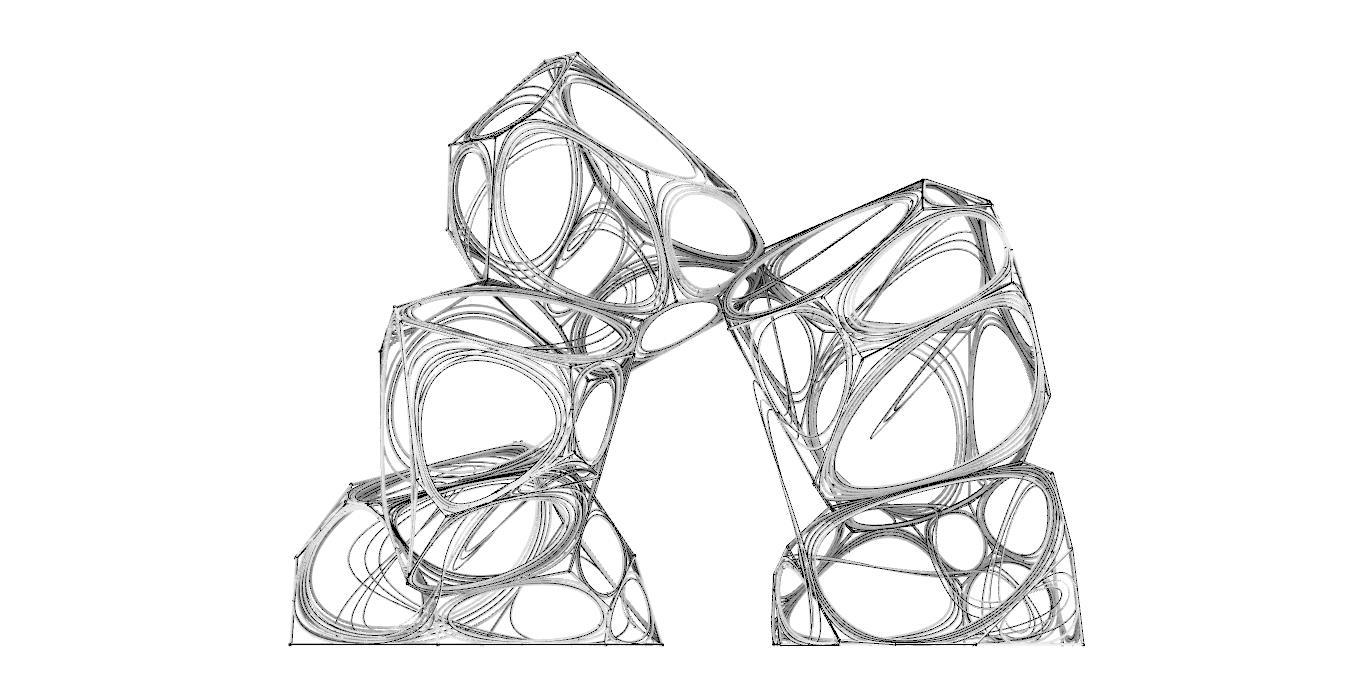

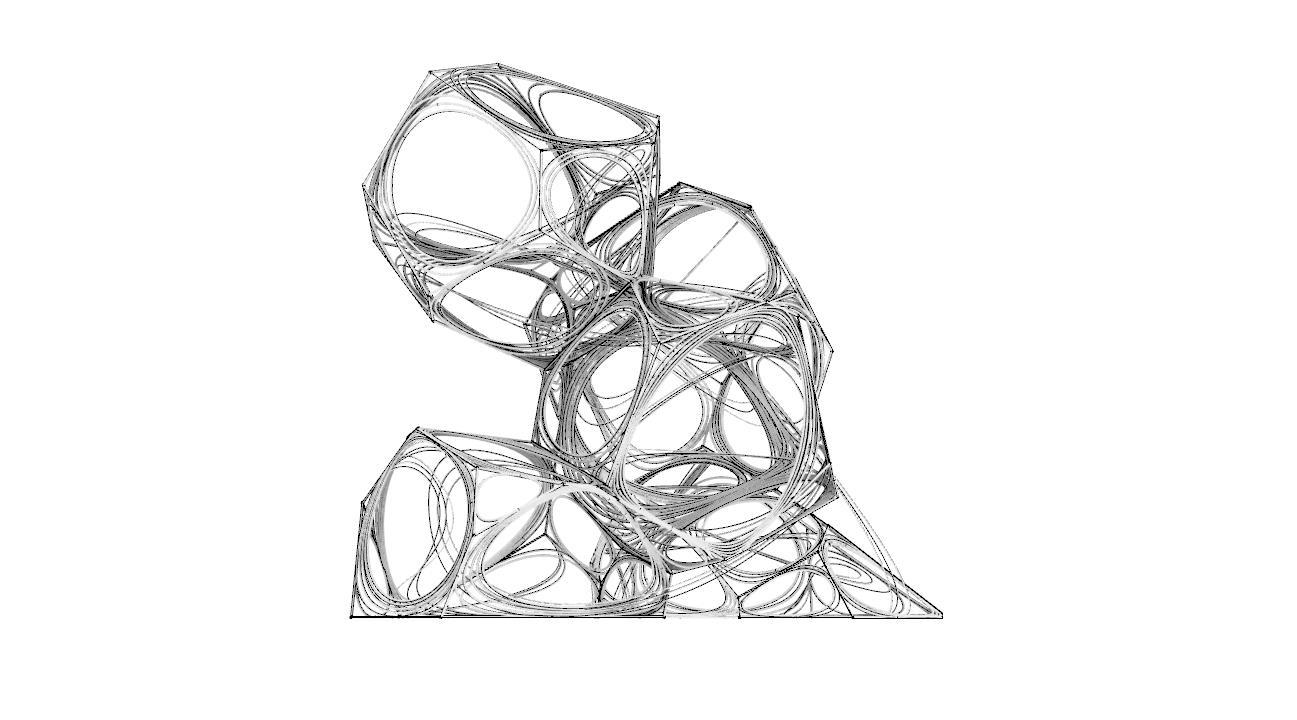

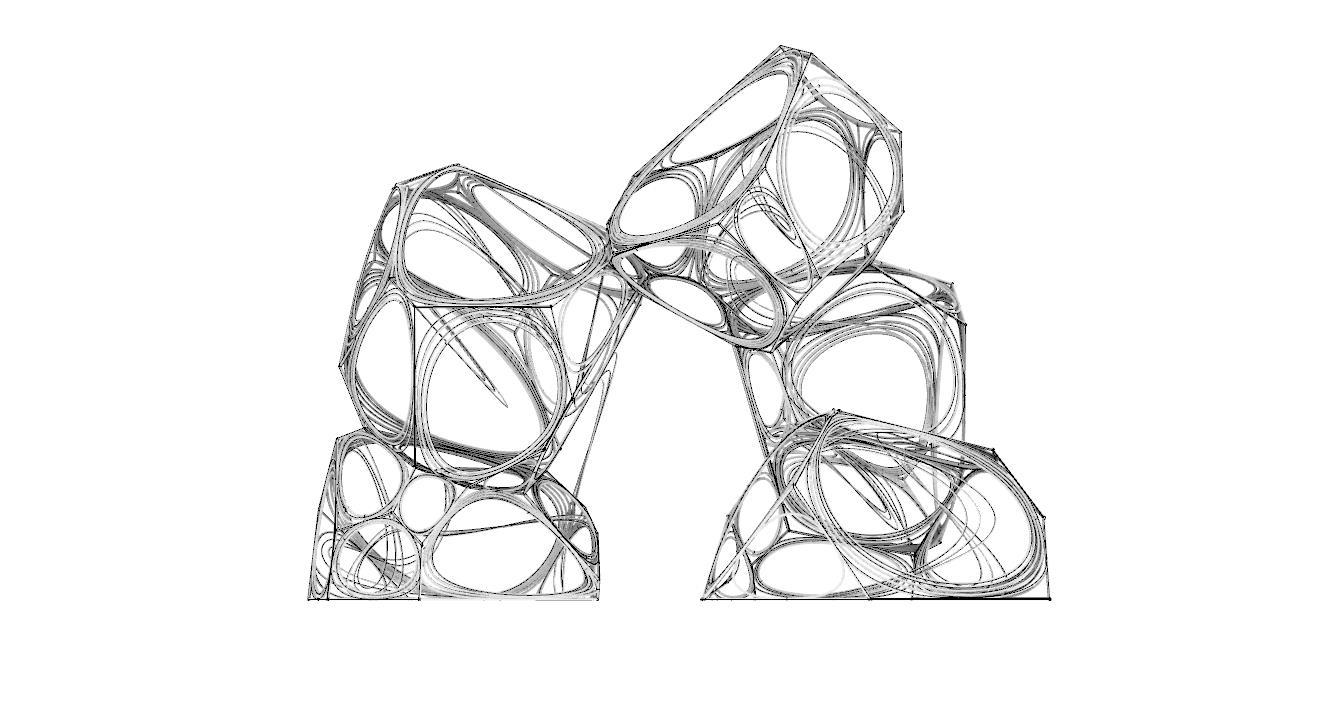

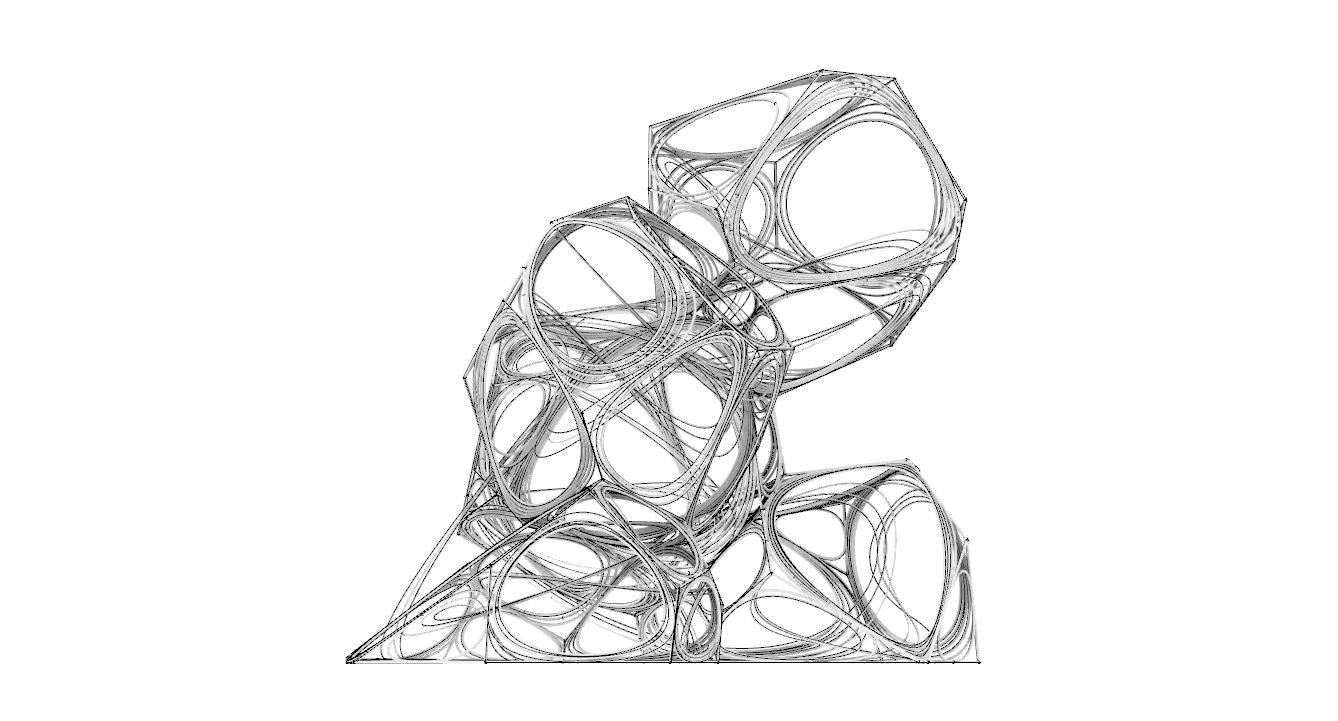

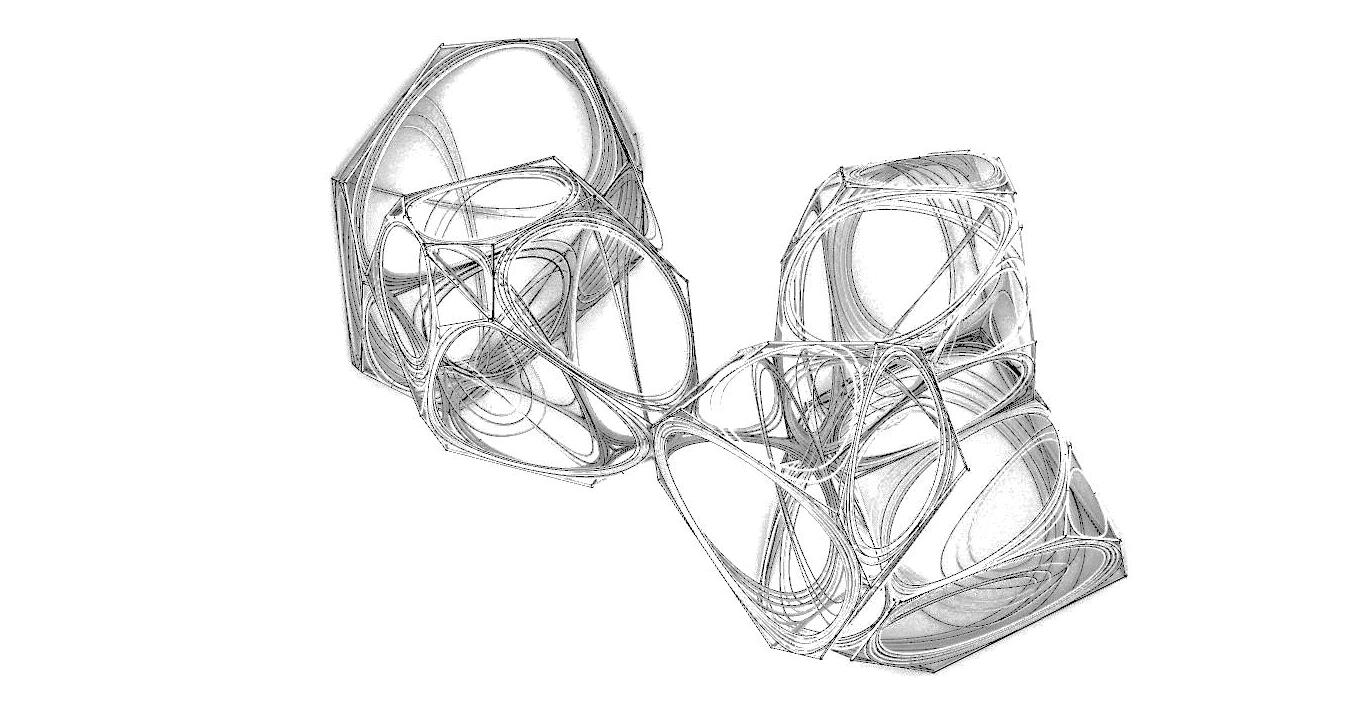

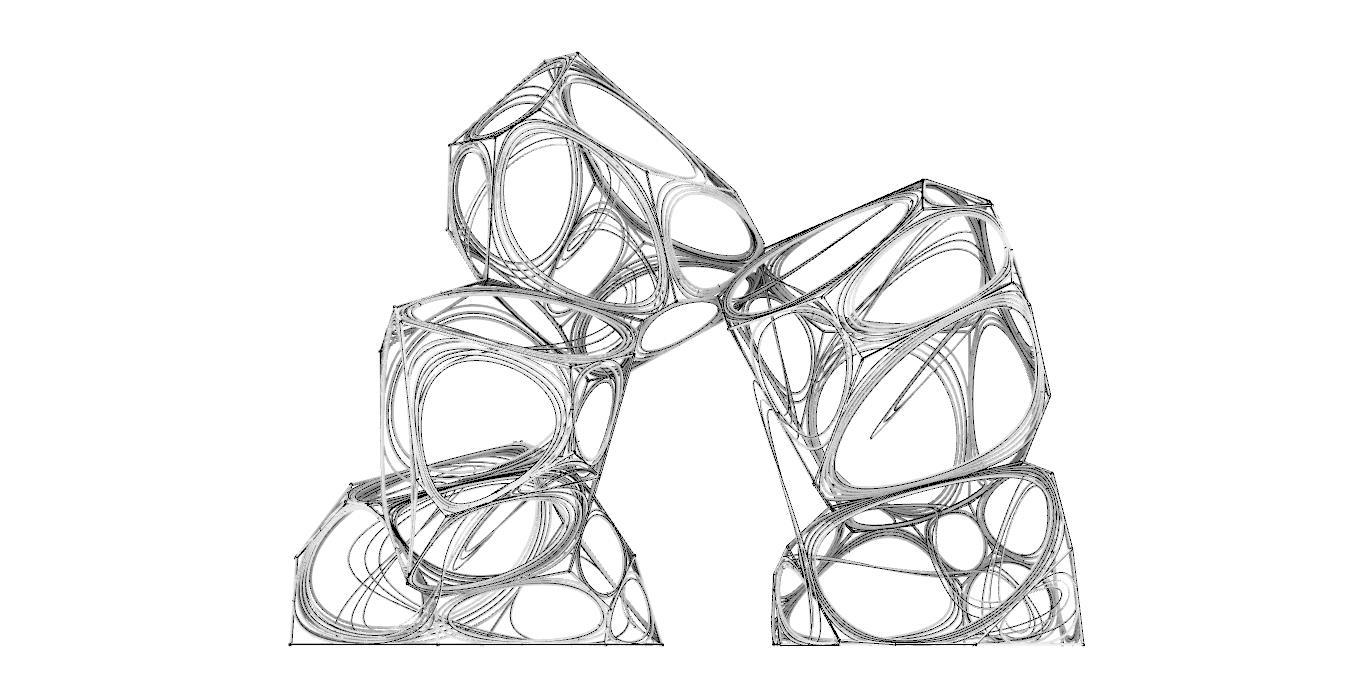

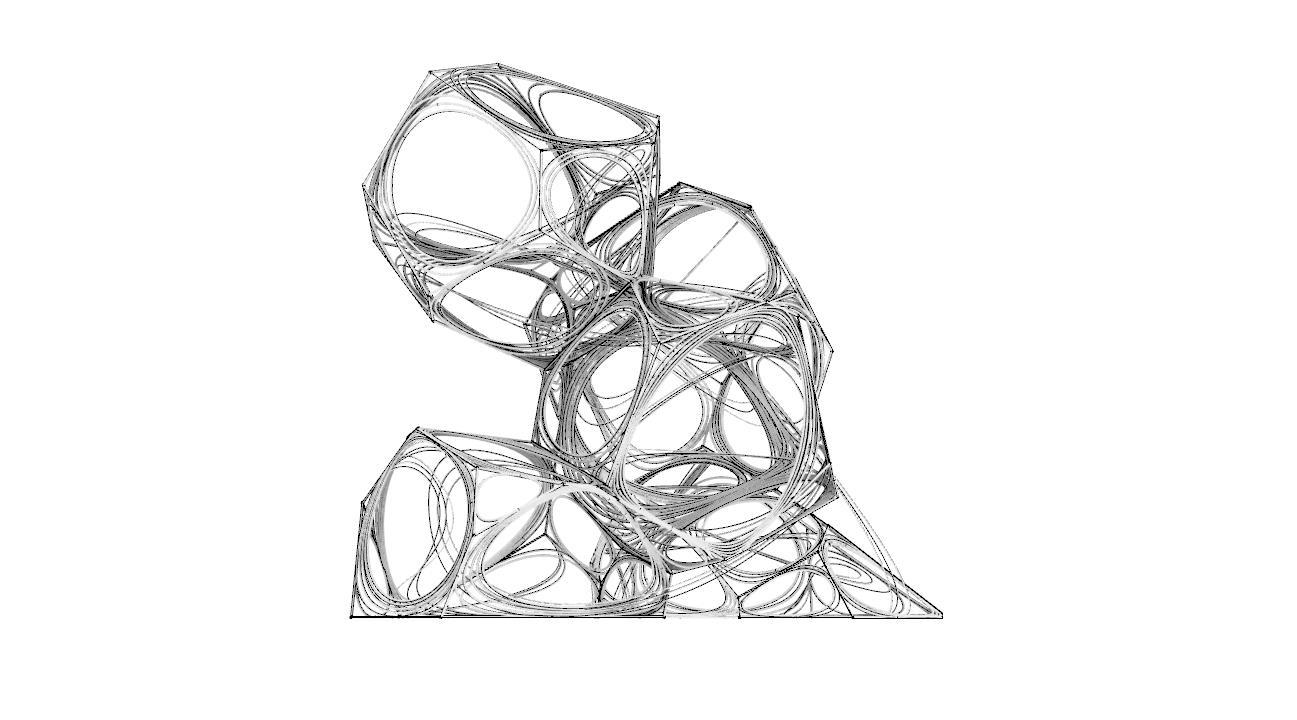

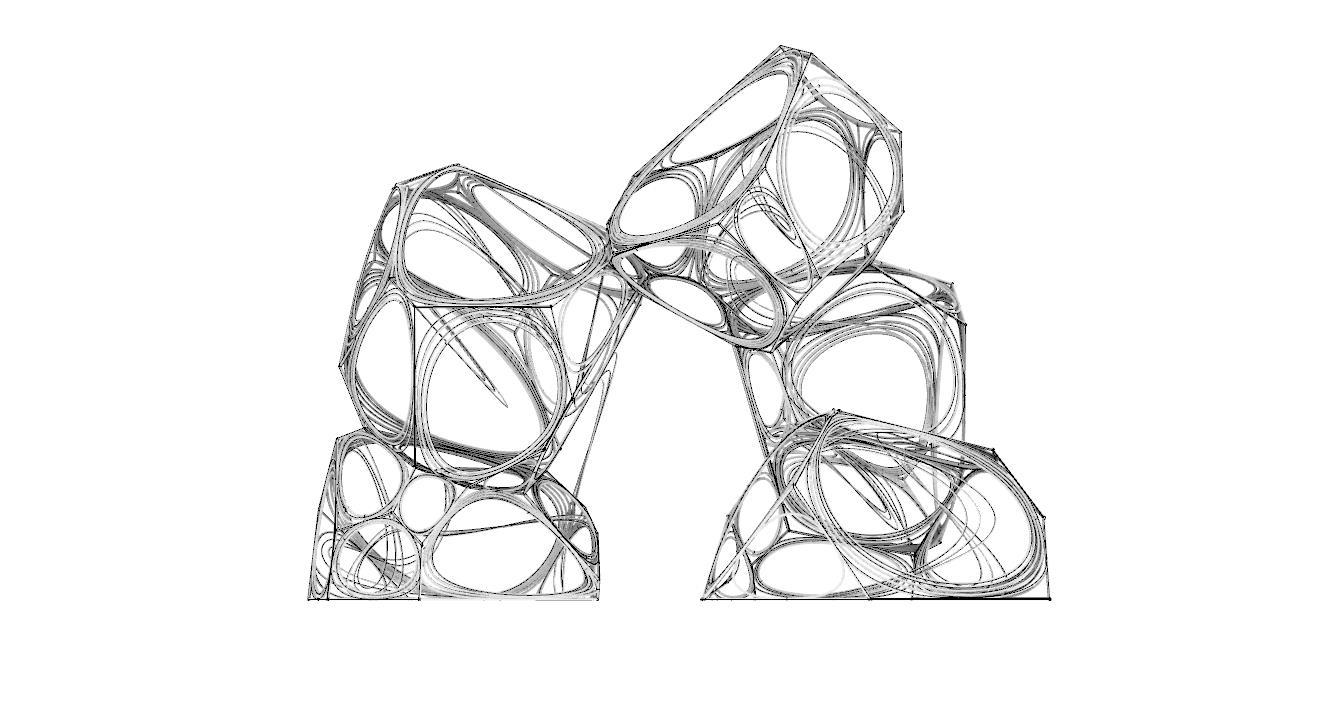

ART802 Computational Form Finding (20Cr.)

The aim of this module is to introduce the students to the use of physical and digital prototyping methods of form-finding for creative design enquiry. It extends the concepts and techniques of design investigations to include principles of computational design. This module will allow the investigation of several design concepts and workflows and create form-finding solutions and workflows that address them.

ART028 Passive Design (10Cr.)

Passive Design is an approach to environmental Design in which emphasis is given to the building envelope and other parts of the building fabric in modifying the climate, using ambient energy to get as close to comfort as possible without using mechanical building services.

ART035 Low Carbon Buildings (10Cr.)

The module aims to introduce the ways buildings use energy, methods of matching building energy demands through renewables and low energy systems, and introduce techniques for assessing the energy footprint and sustainable performance of the building using benchmarking.

ART041 Climate, Comfort and Energy (20Cr.)

This module aims to provide knowledge and understanding of the physical mechanisms through which the built environment uses energy in order to attain human comfort.

ART702 Architectural Technology 3A (10Cr.) The module is intended to familiarise students with principles and information on various aspects of technology relevant to buildings of moderate complexity: Construction & Materiality, Structural Strategies, Building Physics and Science and Building Services.

ART501 The Conservator’s Role (20Cr.)

The module sets out to establish and question an understanding of the role of the built heritage sector at a global and a local level. It introduces both economic and ethical dilemmas that present constant challenges to the theory and practice of building conservation. As an introductory module, it frames the broadest theoretical influences behind current legislation and thinking and anticipates that these may be used to colour judgments made later in the course when addressing case studies. It follows an induction covering research, writing and technical drawing skills.

ART502 Tools of Interpretation (20Cr.)

The module addresses methods for both desk-based research and on-site surveys into and of historic buildings. It further encourages the development of interpretive skills using both methods to form reasoned conclusions about historic buildings’ nature, stability, and date. The presentation of specific and general phenomena by example are used to assist in identifying patterns and exemplars of decay and survival, as well as anomalies. Techniques of surveying will be explained and tested. The Cadw and Historic England (Governmental bodies for statutory protection of the historic environment in Wales and England) levels of the survey will be explained. Common causes of damage and decay will be identified in order to assert real-life exemplars of technical dilemmas.

ART505 Design Tools: Methods of Repair (20Cr.)

A core set of tools understood through an approach to materials will be applied to the repair and conservation of a sequence of building typologies which will rotate annually, providing variety to people taking the module as part of a RIBA, IHBC or RICS CPD programme. Varied approaches to repairing building types will address different building elements and construction methods viewed under varying constraints. The teaching method will be iterative and studio-based to encourage discourse and experimentation.

3.2 Studio Culture and Conduct

The school promotes a convivial and collaborative studio culture. The majority of MA AD students choose to work in the studio, benefiting from shared learning amongst peers. Design studios are a location where students within a thematic studio can meet, where experiences can be shared across studios and where informal tutorials take place.

At the MA AD level, students are expected to develop an autonomous and responsible attitude to their learning and plan their time. Weekly tutorials, seminars, and consultancies should be considered a valuable resource, and students should aim to maximise the benefits they get from these. This is best achieved when students adopt a professional attitude towards their conduct in the school.

This might include:

• Attending all tutorials and consultancies at the allotted time. If a tutorial slot is missed, it may be difficult to reschedule a student to another time.

• Bringing all necessary drawings and models: discussion around a students work can be difficult if key items are missing.

• Ensuring that drawings are presented in a professional manner, using, where necessary, appropriate drawing conventions.

• In group tutorials, listening and contributing towards the discussions on the work of other students.

The school’s design studios should be an inviting, pleasant, clean, and organised space open to all architecture students in the school. MA AD students have 8am - 9pm access access to the studios, but this should be considered a privilege that will be lost if due care and consideration are not given to the school’s property and relevant health and safety obligations. Studios should be kept clean and tidy, and students should ensure that appropriate facilities for cutting, spraying and model making are always used.

Studio culture is significant to the MA AD course, Which is not just the thematic unit but also the physical space of the studio. Everyone is encouraged to work in the school, benefit from contact with each other and staff, and ready access to other facilities. We promote a lively studio environment.

Aims and vision

The School is highly regarded and top-ranked both nationally and internationally. However, no organisation can remain static. It has to change if only to respond to changes in the outside world. Rather than be reactive, it is usually better to be part of the change process to lead the change. That is what we are trying to do within the School. Our goals are:

1 To create “critical mass” in key areas. Expand the number of academic staff to develop research profiles and deliver education programmes in critical areas.

2 To broaden and diversify the educational and research offering the school makes to society so that we are not wholly reliant on a handful of specialisms. The context for both the built environment and architectural education is increasingly diverse, dynamic and uncertain. We aim to flourish, not just cope.

3 To produce graduates with design skills who can operate across the broad spectrum of activity related to the sustainability of the built environment and who can solve the ‘wicked’ problems that involve working with contemporary issues of ambiguity, unpredictability and uncertainty.

In short, we want to spread the WSA experience more widely by building on our success so that others can benefit from what we have to offer. It differs from conventional built environment schools by placing design at the centre. At the heart of this is the knowledge that design can make a positive difference to people’s lives and that our graduates, who already make the world a better place by designing buildings, might be joined by others from the WSA who can bring design thinking and skills to a whole range of problems that face the world. Typically, these problems require interdisciplinary approaches, which architecture thrives on. The school plans an expanded suite of master’s programmes and delivery methods to implement this.

Library

3.3 Supporting facilities Workshop

The Architecture Library is located within the Welsh School of Architecture in Bute Building and is one of eighteen Cardif University site libraries. Its location is exceptional amongst British schools of architecture in that its collection of books, journals, reference and technical literature and audio-visual material is directly accessible to students and staff of the School. In addition to these resources, it holds a rare books collection and provides access to a wide range of online and CD-ROM databases, internet resources and electronic journals.

The workshop is equipped with several benchmounted electrical tools, including two belt sanders, two disc sanders, two bandsaws, a scroll saw and a pillar drill. A number of portable electric tools include three drills, a belt sander, orbital sander, planer and router. Students may use all these items of equipment after induction by the workshop craftsman and a short period of training, which includes specific training in health and safety. There is also a professional combination woodworking machine for use by the workshop craftspersons only, for some of the more heavy-duty project work students require. Across the corridor is a ventilated spray booth. Access usually is available, but graduates are expected to liaise with our craftspersons.

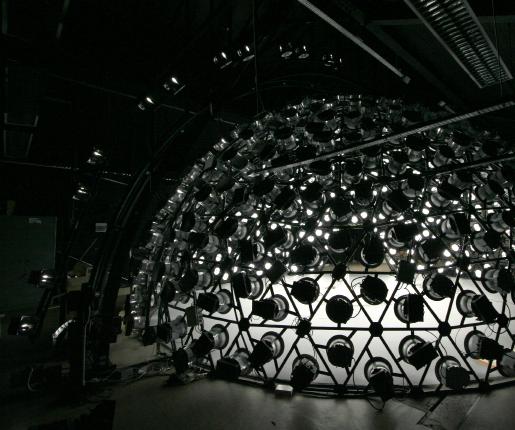

Environmental Laboratory

The environmental laboratory underpins many of the activities of the Architecture Science Group and supports those of the Design Research Unit. The facility offers physical scale modelling, numerical or computational modelling, laboratorybased measurement, field monitoring. The major components of the laboratory are the: SkyDome, computer modelling facilities and the Meteorological Station.

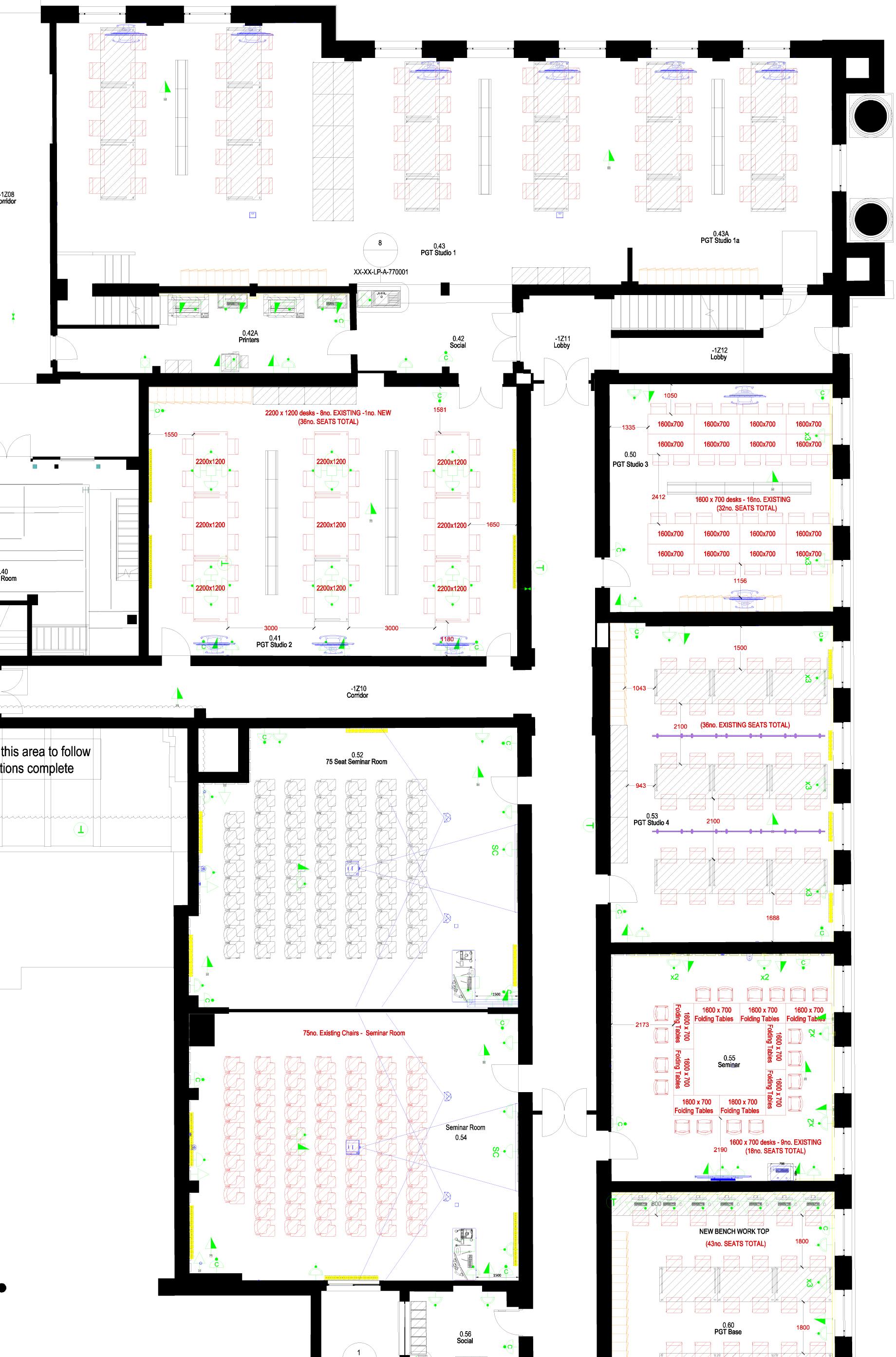

Media Lab

Currently, numerous PCs are located around the design studios, together with A4 scanners and lightboxes. The School supports the use of laptops, and wireless networking is provided. Students have access to a media lab containing ten high specification computers and A1 Plotters, A3 Colour printing, an A4 Black and White Printer, and A3 and A4 Scanners. PGT Design Studio also has a plotter room with two plotters and a printer/photocopier.

The School has has several drones, a video camera, laptops and digital projectors for anyone to use for presentations. In addition to the facilities provided by the School, ‘open-access’ computing facilities are available in the Bute Library and at other locations around the University. Some of these can be blockbooked for teaching purposes.

The School aims to provide students with a wide array of software for computer-aided design and digital presentation, including 3D/CAD (AutoCAD, Sketchup, 3DStudio, Rhino); Digital Media (Adobe Creative Suite); Environmental Design (Ecotect). These are available on the network and are therefore anywhere on campus.

Fab-Lab

The Fad-Lab includes laser cutting facilities, 3D printers, the CNC router and a robotic arm. Access to all facilities should be arranged through the School’s Facilities Manager, who coordinates and manages the demand for resources.

3.4 Unit Leaders and Module Leaders

Dr. Federico Wulff Barreiro (Chair of MA AD)

Unit A: H>D_Contemporary Architecture and Heritage for Socio-Economic Development.

Dr. Federico Wulff is a Senior Lecturer of Architecture and Urban Design and Course Director of the Masters of Architecture Design (MA AD) at the Welsh School of Architecture. He conceives Architectural Design Research (AD-R) at the core of his combined profile as a researcher, educator, and contemporary awardwinning architectural designer. In 2007/2008 he was awarded the Rome Prize in Architecture of the Royal Spanish Academy of Rome, where he completed his European PhD initiated at the ETSAM-Madrid and Paris-Belleville Universities. His research project EMUVE (Euro-Mediterranean Urban Voids Ecology) funded by the European Commission-EU, explores alternative design strategies for re-activating urban contexts in crisis, from the 2008 Great Recession to the ongoing migration crisis. He was awarded the EU-Europa Nostra Grand Prix 2019 for the restoration of a 14thC. mosque in The Alhambra, UNESCO world listed heritage site (Granada, Spain), the most prestigious heritage award at the European Level.

His practice W+G Architects has been awarded 10 first prizes in International Architecture competitions. His projects have addressed a wide range of issues, from public spaces (Eras, Forum) to cooperation projects in developing countries (Ethiopia, Morocco). He has been recently appointed as an international expert member of the Advisory Board for the Regeneration of the campus at the University of Santiago de ChileUSACH, and a guest speaker and workshop leader in Lahore, the capital city of the Pakistani Punjab, focusing on Architectural Design-Research (AD-R) and contemporary architectural design interventions in heritage contexts, This keynote lecture and workshop is sposored by the Institute of Architects of Pakistan-IAP.

Dr Marianna Marchesi

Unit B: EcoLoci

I am a Lecturer in Architectural Design at the Welsh School of Architecture at Cardiff University (UK), a researcher and practitioner. I graduated in Architecture from the University of Ferrara (Italy); then I completed a postgraduate degree in Sustainable Building Design and later a PhD in Sustainable Energy and Technologies at the University of Bozen-Bolzano (Italy) in collaboration with MIT (USA) where I spent a year of study and research. My multidisciplinary background is combined with a decennial experience as a registered architect, academic researcher and teacher in Italy and abroad (US and UK).

In 2018, I was awarded the competitive European Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship, and I joined the Wesh School of Architecture for implementing the research project called CircuBED as a principal investigator. The project focused on exploring how citizens can contribute to the transition to a circular economy in their cities, and specifically it explored social innovation for a circular economy as a change agent.

My research and teaching interests focus on design and innovation for the sustainable development of cities to tackle current challenges. My research is about socio-technical innovations for sustainability and the alignment of changes at different levels of the built environment for sustainable development.

I am particularly interested in supporting upcoming systemic changes for sustainability through developing social, organisational and technological innovations.

Dr.

Hiral Patel Unit C: Learning Environments

My current research and teaching aim to better understand clients and users of the built environments. I am interested in themes of learning, socio-material practices, holistic building performance and adaptation of buildings.

My PhD research theorises the practices of adapting academic library buildings. Based on this research, my consultancy for Higher Education Design Quality Forum (HEDQF) identified research themes for future learning environments in the higher education sector. Building on this, I am co-creating a research agenda for future learning environments to develop new ways of designing and managing higher education spaces. I also provide consultancy for businesses to develop research-based design approaches, which aligns with my design-research teaching activities.

Through a range of funded projects, I have developed the ‘Learning-Space Aligner’ framework to better align learning and space, which I am piloting with university partners and in workplaces. My research on workplaces involved curating the DEGW archive and exploring the linkages between organisational practices and the built environment to help understand the changing nature of ‘work’. Based on this, I am currently co-authoring the third edition of ‘Integrative Briefing for Better Design’.

Since August 2022, I have taken on the role of Director of Engagement at the Welsh School of Architecture.

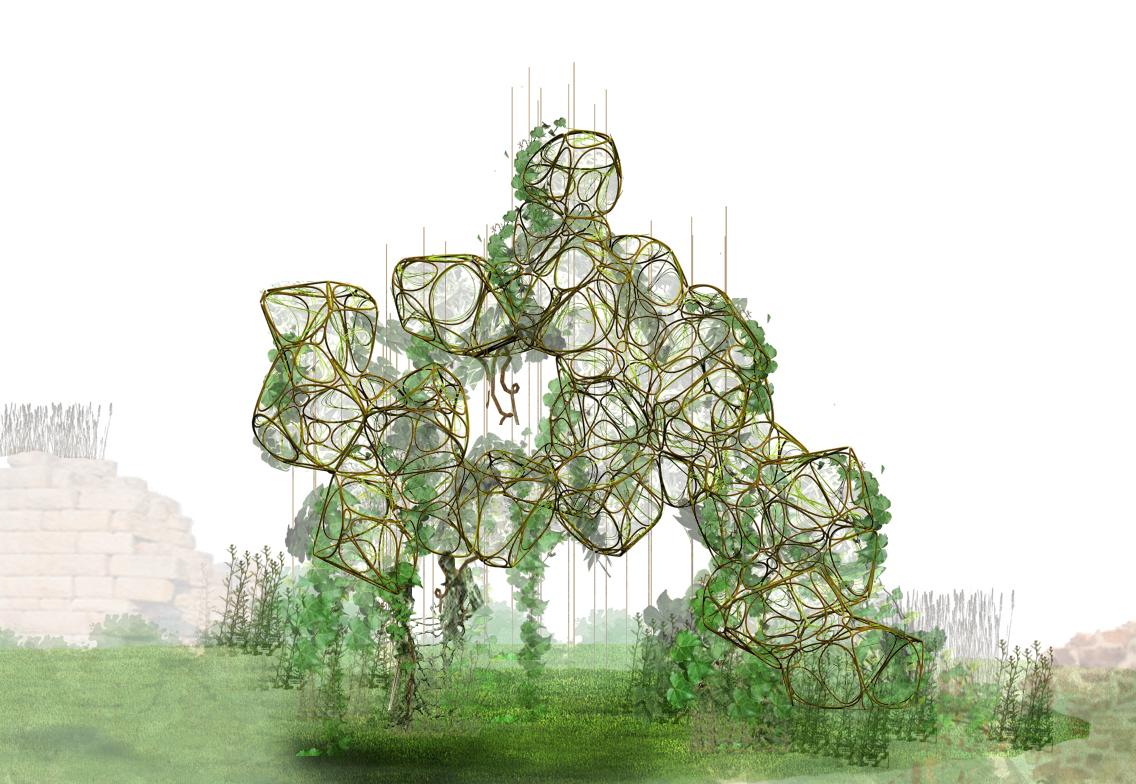

Unit D: Urban Waters

I am an architect, urban designer, and educator with a passion for complexity, ecology, and social processes. I graduated in architecture from IUAV University in Venice, Italy, after a year of studies at ETSAB – the School of Architecture in Barcelona, Spain. I have studied to obtain a postgraduate Master’s Degree in Design Within Historical Contexts and a PhD in Ecological Planning and Urban Design from the University Federico II of Naples, Italy. I have been visiting PhD at the University of Copenhagen (KU Life department) and The Parsons New School in New York.

After moving to the UK in 2013, I joined Ian Ritchie Architects, working on several residential schemes and competitions. In 2018, I founded Unagru, a practice that aims to expand the agency of ecological thinking and concepts at every scale. The office’s main focus has been on the private residential scale, small collective and research on public spaces.

My research interests revolve around the intersection between humans and nature. I am particularly interested in water as a scarce resource and an incredibly powerful vehicle for urban structuring and reclamation. I am also interested in critical architecture, architectural practice, flows of materials and energy, and urban economy.