13 minute read

UNIT A. H>D_Contemporary Architecture and Heritage for Socio-Economic Development

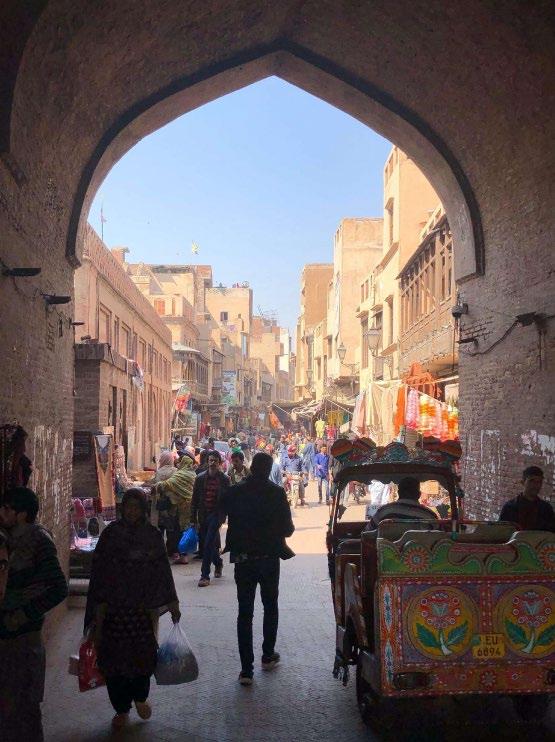

Re-imagining the History and the Future of the Historic Walled City of Lahore. Joint Unit_WSA and the Department of Architecture of the University of Engineering and Technology of Lahore (DoA-UET), Pakistan.

Introduction

Advertisement

Historically, the urban and architectural development of Lahore’s historic walled city has been very fragmented and unstructured, devoid of any proper planning or rationale behind it. This chaotic development has been particularly problematic since the country’s independence in 1947 when the Pakistani society regained its agency for rethinking and planning their country. Since then and along the same lines, the Pakistani architectural profession has been unable to make informed planning decisions for the recovery and reorganisation of Lahore’s historic walled city and the recovery of its heritage values from sensitive socio-economic, inclusive and cultural approaches, aiming for supporting for supporting its sustainable preservation and development for future generations. Instead, for decades the focus has been on unfortunate short-term and fragmented monetary benefits for landowners and developers with explicit neglect of its historical, social and heritage values as its key assets. As a result, the highly valued heritage of this area has undergone profound degradation processes throughout time, including issues of abandonment, criminality, deprivation and underused spaces.

The H>D Unit focuses on understanding the importance of these heritage values from a contemporary architectural standpoint beyond a mere conservationist approach. The aim will be to reimagine contemporary architectural and urban design interventions that would re-establish a sensitive dialogue with its heritage values while reactivating its activity. A key aspect will be to enhance the local citizenship’s awareness of the importance of their heritage values, key for supporting the socio-economic development of the community. Students will investigate the past and the current state of heritage in the walled city and how its usage and importance have evolved throughout time, including all aspects and processes that have contributed to its degradation in different periods to the present. They will also explore other important features defining the character of the walled city such as the very important religious character and the built structures signifying it. In the next stage, they will identify potential intervention sites where current degradation and unplanned uses and activities are harming to an extreme extent the rich historical, cultural, and social aspects that have informed the heritage values of the walled city. A multi-scalar contextual analysis is required for understanding this multi-layered complexity and for making interpretations according to relevant themes arising. On the grounds of previous analytical stages, the students will develop contemporary interventions at public space and architectural scales, by establishing a sensitive dialogue with these complex heritage contexts. The new interventions will be considered as an additional page added to this rich multi-layered history.

The final aim of the H>D WSA-UET Studio will be to develop and test Architectural Design Research (AD-

R) strategies at multiple scales for the reactivation of neglected and abandoned spaces within the walled city of Lahore by promoting its heritage values while enhancing the local community’s participation and empowerment in a co-design process. The final objective will be the urban and architectural transformation of these intervention sites together with a profound positive impact on their surrounding urban and social fabric.

This joint H>D WSA-UET Design Research Unit will articulate a close collaboration with the most important institutional actors in the area, namely the public sector institution of Lahore Walled City Local Authority and the private organisation of The Aga Khan Cultural Services-Pakistan. Using design research tools, techniques and methods, the aim will be to develop preliminary design research proposals co-produced with our institutional partners and the local community. This will be the grounds for the students’ architectural and urban design professional projects for the area during the springtime and during the Stage 2 advanced dissertations.

As Bloomfield (2007: 6) argues, [...] “identifying and creating ‘third spaces’ away from the dualism of either/or, them vs. us – places which have no exclusive belonging to one side or the other and are many-sided, a space open to all. Usually, these spaces will be open-ended, self-managed and nonhierarchical, encouraging equal participation”.

Reading List:

Walled City of Lahore

• Ali, R. H. (1990). Urban conservation in Pakistan: a case study of the walled city of Lahore. Architectural and Urban Conservation in the Islamic World, 79.

• Bajwa, Khalid & Smets, Peer. (2013). The Walled City of Lahore: The Modes of Marginality and Specificity of Spatial Structure and Urban Life.

• Batool, T. (2016). Conservation in the Walled City of Lahore: How state efforts affect the urban fabric of heritage cores. American University.

• Jodidio Ph. (2019) ed., Lahore: A Framework for Urban Conservation. Munich: Prestel.

• Peck, L. (2018). Lahore: The Architectural Heritage. Roli Books Private Limited.

• Zahid, A., & Misirlisoy, D. (2021). Measuring place attachment, identity, and memory in urban spaces: case of the Walled

• City of Lahore, Pakistan. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 45(2), 171-182.

Books and Articles on Interculturality, Social diversity, Urban Agency, Participation, Co-design

• Aelbrecht, P.S. (2016). ‘Fourth places: the contemporary public settings for informal social interaction among strangers’. Journal of Urban Design 21(1), pp. 124–152. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1106920.

• AWAN N., SCHNEIDER T., TILL J. (2011), Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture, London: Routledge.

• BUNDELL-JONES, P., PETRESCU, D. AND TILL, J. (eds., 2005) Architecture and Participation. Abingdon: Spon Press.

• GEHL, J. (2011). Life between buildings: using public space. Washington DC: Island Press.

• GROTH, J. and CORIJN, E. (2005) Reclaiming Urbanity: Indeterminate Spaces, Informal Actors and Urban Agenda Setting. Urban Studies 42(3): 503–526, doi: 10.1080/00420980500035436.

• LEFEBVRE, H. (1991a), The Production of Space, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

• SENNETT, R. (2011). ‘Boundaries and borders’. In: Burdett, R. and Sudjic, D. eds. Living in the endless city. Washington, D.C.: Island press, pp. 324-331.

• SOLA-MORALES I. (1995), “Terrain Vague” in Territorios, Barcelona: G.G., 181193.

• Source: Terrain Vague – de Sola Morales – Landscape+Urbanism (landscapeandurbanism.com)

Dr. Federico Wulff and EMUVE Unit European Research project

• Wulff Barreiro F., Brito Gonzalez O. (2022), “The multi-scalar production of intercultural urban landscapes. Inter-Cultural Nodes as urban and social reactivators: the case of Ballarò, Palermo” in Generosity and Architecture, Edited by Mhairi McVicar et al., London: Routledge.

• The multi-scalar production of intercultural urban landscapes: Inter-C (taylorfrancis. com)

• EMUVE European Research Project, funded by the European Commission

Unit B. EcoLoci

Overview

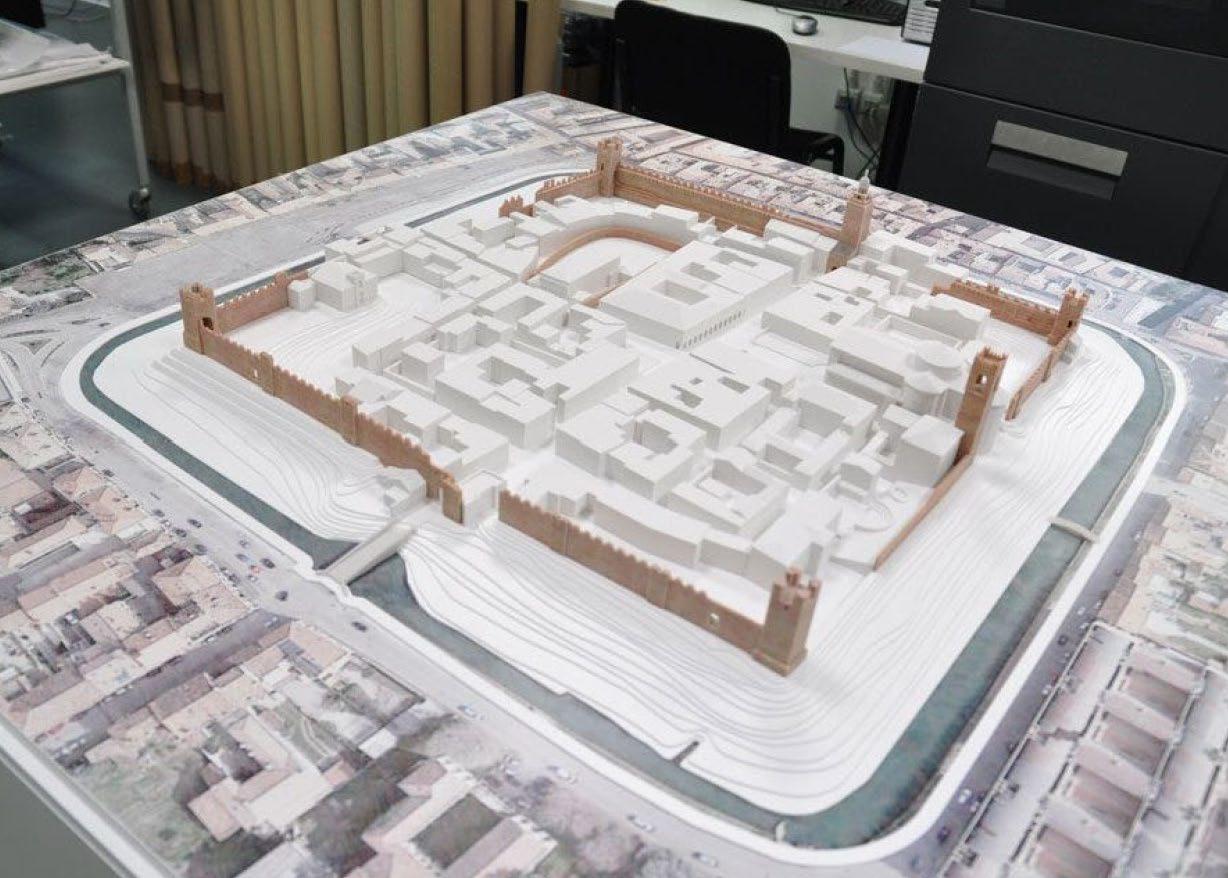

Cities are centres for innovation with a high concentration of resources, capital, data, and talent spread over a relatively small geographic area. Twothirds of us will be living in urban areas by 2050. Despite taking up just 2 per cent of global landmass, our urban centres consume more than 75 per cent of natural resources, are responsible for over 50 per cent of solid waste and emit up to 60 per cent of greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss and the consequent impact on society and economy. There is strong evidence suggesting that the nature and scale of the challenges faced by cities demand much more than traditional approaches. Cities need to be innovative in designing and testing new solutions to respond to increasingly complex and interconnected local challenges related to sustainable urban development. The design unit aims through design research at envisioning and designing responses to identified systemic challenges in the urban environment for promoting sustainable development. The overall ambition of the unit is to foster the development of urban innovations to provide ambitious and creative ideas as enablers of sustainable development. The design unit will focus on Castelfranco Veneto (Italy), a medieval walled town in North Italy. Its town wall infrastructure (town walls and its green belt) is strongly linked to the identity of the local community, but it is currently neglected. Key issues and challenges include their extent, their relationship with the surrounding urban context, and their role/ function within the townscape. Moreover, a set of historical public buildings and open spaces linked to the wall infrastructure in the townscape are currently underused. These precious resources are critical to the effective and sensitive sustainable development of the walled town which can create valued places for residents and tourists while addressing urban challenges.

Castelfranco’s town wall infrastructure and linked public buildings and open spaces represent an opportunity for the city to create a network of innovative strategic actions for supporting the sustainable development of the town and strengthening the identity of the local community. Proposed design research themes are as follows:

1. Designing in a spirit of circularity, carbon neutrality and sustainable living

2. Preserving and transforming cultural heritage for sustainable development

3. Adapting and transforming buildings for community/collective purposes and sustainable living

4. Regenerating urban spaces

Work Plan

The design unit will engage students in design research to build skills for thinking critically, learning independently and tackling complex challenges. Through design research, students will analyse the context and define challenges to answer within the project, define appropriate methods and approaches of research to inform the process, develop solutions to address identified challenges and deliver a design proposal integrated into a dissertation thesis. The design unit will consist of two main parts implemented within the proposed topic: Stage 1: architectural design research (ADR) and Stage 2: dissertation thesis (DT). In the first stage, students will explore the context, define challenges, develop ideas to address them and deliver a comprehensive urban-architectural design proposal through design research. In the second stage, they will integrate the design research proposal into a dissertation thesis. Learning and teaching will be performed through inquiry-based learning by a mix of activities (group work, individual work, flipped learning sessions combined with gaming sessions and focus groups, reflective practice activities, face-to-face group and individual tutorials, a unit trip to visit the place in Italy, peer-review, self-assessment, and crits scheduled across the year combined with written feedback). Research activities will inform the design as well as research will be implemented through design.

Reading List

City

• Aldo Rossi (1999. The architecture of the city, Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT

• Lynch Kevin (1964). The image of the city. Cambridge, Mass.; London: M.I.T. Press

• Bently, I., Alcock, A., Murrain, P., McGlynn, S., Smith, G. (2005). Responsive environments. Architectural Press.

• Gehl, 2020. Projects. Available at: https://gehlpeople.com/work/projects Architecture

• Norberg-Schulz Christian (1980), Genius loci: towards a phenomenology of architecture. New York: Rizzoli, 1980

• Carlos Marti Aris (2021) The Variations of Identity: The type in architecture. Cosa Mentale

• Frampton Kenneth (2001), Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Architecture. The MIT Press

• Zumptor Peter (2010) Thinking Architecture. Birkhäuser; 3rd, expanded ed. edition

• Deplazes Andrea (2018) Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures. A Handbook. Birkhäuser; 4th edition

• Ching, F. (2014). Architecture: form, space and Order. Wiley

• Brand, S. (1997). How Buildings Learn. New York: W&N

• Kendall, S., Teicher, J. (2010). Residential Open Building. Spon Press

• Timberlake, J. & Kieran, S. (2011). Cellophane house. KieranTimberlake

• Sustainable built environment

• Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, Jeremy Till (2013). Spatial agency: other ways of doing architecture. Routledge

• Hiltrud Pötz, Pierre Bleuzé (2016). Green-blue grids. Manual for resilient cities. Atelier GROENBLAUW

• Anders Lendager & Ditte Lysgaard Vind (2018). A changemaker’s guide to the future. Lendager Group

• Ezio Manzini, Francois Jegou (2003). Sustainable Everyday. Scenarios of urban life. Edizioni Ambiente

• Stewart Brand (1997). How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built. New York: Viking; 1994

Circular Economy in Urban level

• Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017. What is the circular economy? Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept

• Ellen MacArthur Foundation, The Future of Cities. Available at: https://www. ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/future-of-cities.pdf

• Ellen MacArthur Foundation & Arup, 2019. Circular economy in cities. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/our-work/activities/circular-economyin-cities

• Arup, 2016. The Circular Economy in the Built Environment. Available at: https:// www.arup.com/perspectives/publications

Circular Economy in Building level

• Cheshire, D. 2016. Building Revolutions: Applying the Circular Economy to the Built Environment. RIBA Publishing (available in the Cardiff University Library)

• GXN, 2018. Building a circular future. Available at: https://gxn.3xn.com/wp-content/ uploads/sites/4/2018/09/Building-a-Circular-Future_3rd-Edition_Compressed_ V2-1.pdf

• NL DGBC, Metabolic, SGS Search & Circle Economy, 2018. A framework for circular buildings. Available at: https://www.metabolic.nl/publications/a-frameworkfor-circular-buildings-breeam/

• UK Green Building Council, 2019. Circular economy guidance for construction clients. Available at: https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/circular-economy/

• UK Green Building Council, 2019. Circular Economy Implementation Packs for Reuse and Products as a Service. Available at: https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/ circular-economy/

• Arup, 2017. The urban bio-loop. Available at: https://www.arup.com/perspectives/ publications/research/section/the-urban-bio-loop

• Arup, 2018. The Industrial Resolution. Available at: https://www.arup.com/ perspectives/publications/books/section/the-industrial-resolution

• Arup, 2016. The circular building. Available at: https://www.arup.com/perspectives/ the-circular-building

• GXN, 2018 Circle house. Denmark’s first circular housing project. Available at: http://grafisk.3xn.dk/files/permanent/CircleHouseBookENG.pdf

• Product level

• IDEO & Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2018. The Circular Design Guide. Available at: https://www.circulardesignguide.com/

• Ellen MacArthur Foundation & Arup, 2019. Urban products system. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/Products_All_Mar19. pdf

Unit C. Learning Environments - Design Research Laboratory II (LE-DR Lab II)

Dr. Hiral Patel

Future of the library - a conceptual challenge

The intellectual landscape: Academic libraries are the heart of universities. There is a tendency in the sector to centralise library operations instead of having departmental libraries. The case for having a centralised or departmental approach to libraries depends on the institution’s spatial and historical contexts. Despite such differences in the organisational approach to academic libraries, the libraries are non-disciplinary spaces where books, objects and readers/users from different academic disciplines coalesce. Since the 1990s, the role of physical library buildings has been questioned as written materials have become increasingly accessible through an electronic medium, evoking “a paperless library” (Thomas, 2000). Another tension in library design has been around the increasing development of collaborative study spaces at the expense of quiet study spaces, while the latter remains in high demand (HEDQF, 2019). While a range of library refurbishments have focused on the needs of undergraduate students, the role of the library in enabling and supporting research and the creation of new knowledge is also critical. Looking beyond the institution, the university library could be the gateway to the university and build university and city connections (cf. Quinn, 2022). Thus, the library building has been continually subjected to the identity politics of ‘what is a library?’ (Mol, 1998).

Socio-material interactions – a theoretical perspective

The theoretical lens of socio-material practices offers one avenue to explore the question of ‘what is a library?’ (Patel and Tutt, 2018). By conceiving the ontology (what is something?) of a library as not situated only in bricks and mortar but in the interactions between social and material. Moreover, such an ontological shift could highlight different versions of a library that co-exist and the politics of leveraging some versions over the other. The unit will conceptually test the ideas of architecture, particularly through the lens of socio-material practices and explore/challenge/extend the theoretical boundaries of socio-materiality through investigating experience.

Nature of the design propositions: The LE-DR Lab aims to investigate the spatial, digital and organisational strategies to address the challenges presented above. The spatial challenges relate to the design of the form and function at different physical scales ranging from “chair to the city”. The digital challenges relate to how technological interactions could be enhanced and altered through the design proposition. This strand could also explore how the physical and virtual environments interact and complement each other. The organisational challenges relate to how the library services could be designed to achieve its strategic aims alongside the architectural design. This could be explored by taking a service design approach to integrating architectural design with how users could better access library facilities and services. All three dimensions must be jointly addressed when devising architectural propositions.

Future of the library - a contextual challenge

The LE-DR Lab II will analyse existing library provisions on Cardiff University’s Cathays Campus and develop propositions for a future library for the campus. The design propositions will be formed by adopting a design-research approach and connecting with existing literature and precedents to make a novel contribution to our knowledge of library spaces. The design propositions could focus on one of the following typologies while also considering interconnections between them to create hybrid typologies:

• Knowledge spaces: 1. Library as a place for social learning 2. Library as a place for knowledge creation

• Collection spaces: 1.The library of objects 2. Digital scholarship hub

• Community spaces: 1. University library as a cultural institution 2. Library as an enabler of the university’s civic mission

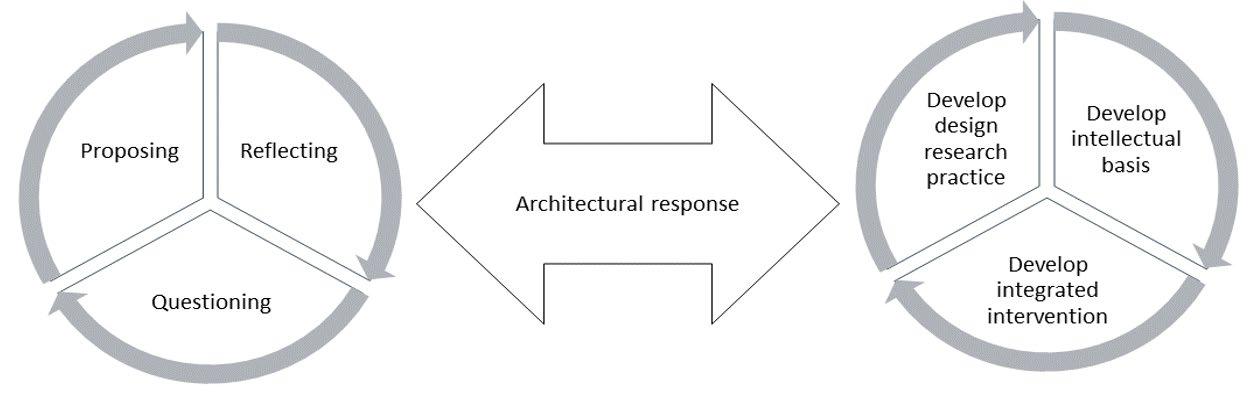

Developing your own design-research method: The design-research approach will engender a continuous iterative dialogue between the conceptual and contextual challenges. LE-DR Lab will collectively progress the knowledge base for the university campus as a whole through design-research and conduct a focused exploration of specific typologies individually. Hence, students will develop their unique design-research methodology based on their research aims and questions. In developing their design-research approach, the students can draw on various design research methods.

User research: It will be essential for each student to identify key user groups for their typology and devise and implement user research. In creating the user research plan, the emphasis would be given to physical models and tools (games, cultural probes, Lego, sketching, model making, photographs, journey maps) to engage users, and a complimentary virtual engagement might be carried out as well.

Campus as a living laboratory: LE-DR Lab is based on mobilising Cardiff University campus as a Living Lab, where students can learn first-hand about the challenges and develop design responses based on their individual and collective learning experiences. The unit will work collaboratively with the student community and library staff in shaping the project briefs and testing ideas. Living lab programmes have been claimed to enhance the sustainability of university campuses. Moreover, libraries are particularly suited as living labs as they are interdisciplinary spaces where students from all subjects can interact. By transforming libraries into living labs, the library spaces can act as a pedagogical tool for students to gain awareness of several challenges facing higher education and the built environment sectors.

Developing your design proposition: The design research process involves iterations between questioning, proposing and reflecting. The ongoing testing of emerging solutions allows personal designresearch practice development based on a student’s values, priorities and strengths. The critical lesson to learn is choosing the suitable method or tool to answer the design research question being explored and continuously reflecting on their practice through the reflective diary.

Reading List

• HEDQF (2019) ‘Social learning environments: student views of their university’, [Online]. Available at https://www.hedqf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HEDQF_ Social-Learning-Spaces_Final.pdf.

• Mol, A. (1998) ‘Ontological Politics. A Word and Some Questions’, The Sociological Review, vol. 46, pp. 74–89 [Online]. DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.46.s.5.

• Patel, H. and Tutt, D. (2018) ‘“This building is never complete”: Studying adaptations of a library building over time’, in Sage, D. and Vitry, C. (eds), Societies under Construction, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 51–85.

• Quinn, K. (2022) ‘The University Library as Bellwether: Examining the Public Role of Higher Education through Listening to the Library’, Civic Sociology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–12 [Online]. DOI: 10.1525/cs.2022.32635.

• Thomas, M. A. (2000) ‘Redefining library space: Managing the co-existence of books, computers, and readers’, Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 408–415 [Online]. DOI: 10.1016/S0099-1333(00)00161-0.